curiosity

by alberto manguel

Curiosity

This page intentionally left blank

ALBERTO MANGUEL

Curiosity

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright © 2015 by Alberto Manguel, c/o Guillermo Schavelzon & Assoc., Agencia Literaria, www.schavelzon.com. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

"O Where are you Going," copyright © 1934 and renewed 1962 by W. H. Auden; from W. H. Auden: Collected Poems, by W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1934 by W. H. Auden, renewed. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

"The Panther," translation copyright © 1982 by Stephen Mitchell; from Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

"Things to Come," from Collected Poems: 1929—1974, by James Reeves. Reprinted by permission of the James Reeves Estate.

Designed by Sonia L. Shannon. Set in A Gos type by Integrated Publishing Solutions. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Manguel, Alberto.

Curiosity / Alberto Manguel. pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-18478-5 (hardback)

1. Manguel, Alberto—Books and reading. 2. Literature—Appreciation. I. Title. PR9199.3.M34845C87 2015 8i4'.54—dc23

[B] 2014034697

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

i0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 i

To Amelia who, like the Elephant's Child, is so full of 'satiable curtiosity. With all my love.

This page intentionally left blank

CONTENTS

Introduction i

What Is Curiosity? 11

What Do We Want to Know? 31

How Do We Reason? 49

How Can We See What We Think? 65

How Do We Question? 83

What Is Language? 107

Who Am I? 127

What Are We Doing Here? 147

Where Is Our Place? 165

How Are We Different? 183

What Is an Animal? 20i

What Are the Consequences of

Our Actions? 219

What Can We Possess? 235

How Can We Put Things in Order? 255

What Comes Next? 273

Why Do Things Happen? 295

What Is True? 3ii Notes 329 Acknowledgments 363 Index 365

This page intentionally left blank

Curiosity

INTRODUCTION

On her death bed, Gertrude Stein lifted her head and asked: "What is the answer?" When no one spoke, she smiled and said: "In that case, what is the question?"

—Donald Sutherland, Gertrude Stein:

A Biography of Her Work ^

I am curious about curiosity.

One of the first words that we learn as a child is why. Partly because we want to know something about the mysterious world into which we have unwillingly entered, partly because we want to understand how the things in that world function, and partly because we feel an ancestral need to engage with the other inhabitants of that world, after our first babblings and cooings, we begin to ask "Why?"1 We never stop. Very soon we find out that curiosity is seldom rewarded with meaningful or satisfying answers, but rather with an increased desire to ask more questions and the pleasure of conversing with

(Opposite) Virgil explains to Dante that Beatrice sent him to show Dante the right path. Woodcut illustrating Canto II ofthe Inferno, printed in 1487 with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library,

Yale University)

others. As any inquisitor knows, affirmations tend to isolate; questions bind. Curiosity is a means of declaring our allegiance to the human fold.

Perhaps all curiosity can be summed up in Michel de Montaigne's famous question "Que sais-je?": "What do I know?" which appears in the second book of his Essays. Speaking of the skeptic philosophers, Montaigne remarked that they were unable to express their general ideas in any manner of speech, because, according to him, "they would have needed a new language." "Our language," says Montaigne, "is formed of affirmative propositions, which are contrary to their thinking." And then he adds: "This fantasy is better conceived through the question 'What do I know?,' which I carry as a motto on a shield." The source of the question is, of course, the Socratic "Know thyself," but in Montaigne it becomes not an existentialist assertion of the need to know who we are but rather a continuous state of questioning of the territory through which our mind is advancing (or has already advanced) and of the uncharted country ahead. In the realm of Montaigne's thought, the affirmative propositions of language turn on themselves and become questions.2

My friendship with Montaigne dates back to my adolescence, and his Essays have since been for me a kind of autobiography, as I keep finding in his comments my own preoccupations and experiences translated into luminous prose. Through his questioning of commonplace subjects (the duties of friendship, the limits of education, the pleasure of the countryside) and his exploration of extraordinary ones (the nature of cannibals, the identity of monstrous beings, the use of thumbs), Montaigne maps out for me my own curiosity, constellated at different times and in many places. "Books have been useful to me," he confesses, "less for instruction than as training."3 That has been precisely my case.

Reflecting on Montaigne's reading habits, for example, it occurred to me that it might be possible to make some notes on his "Que sais-je?" by following Montaigne's own method of borrowing ideas from his library (he compared himself as a reader to a bee gathering pollen to make his own honey) and projecting these forward into my own time.4

As Montaigne would have willingly admitted, his examination of what we know was not a new venture in the sixteenth century: questioning the act of questioning had much older roots. "Whence then cometh wisdom?" asks Job in his distress, "and where is the place of understanding?" Enlarging on

Job's question, Montaigne observed that "judgment is a tool to use on all subjects, and comes in everywhere. Therefore in the tests that I make of it here, I use every sort of occasion. If it is a subject I do not understand at all, even on that I essay my judgment, sounding the ford from a good distance; and then, finding it too deep for my height, I stick to the bank."5 I find this modest method wonderfully reassuring.

According to Darwinian theory, human imagination is an instrument of survival. In order better to learn about the world, and therefore be better equipped to cope with its pitfalls and dangers, Homo sapiens developed the ability to reconstruct outer reality in the mind and to conceive situations that it could confront before actually encountering them.6 Conscious of ourselves and conscious of the world around us, we are able to build mental cartographies of those territories and explore them in an infinite number of ways, and then choose the best and most efficient. Montaigne would have agreed: we imagine in order to exist, and we are curious in order to feed our imaginative desire.

Imagination, as an essential creative activity, develops with practice, not through successes, which are conclusions and therefore blind alleys, but through failures, through attempts that prove to be mistaken and require new attempts that will also, if the stars are kind, lead to new failures. The histories of art and literature, like those of philosophy and science, are the histories of such enlightened failures. "Fail. Try again. Fail better," was Beckett's summation.7

But in order to fail better we must be able to recognize, imaginatively, those mistakes and incongruities. We must be able to see that such-and-such a path does not lead us in the aspired direction, or that such-and-such a combination of words, colors, or numbers does not approximate the intuited vision in our mind. Proudly we record the moments in which our many inspired Archimedes shout "Eureka!" in their baths; we are less eager to recall the many more in which those, like the painter Frenhofer in Balzac's story, look upon their unknown masterpiece and say, "Nothing, nothing! . . . I'll have produced nothing!"8 Through those few moments of triumph and those many more of defeat runs the one great imaginative question: Why?

Our education systems today by and large refuse to acknowledge the second half of our quests. Interested in little else than material efficiency and financial profit, our educational institutions no longer foster thinking for its own sake and the free exercise of the imagination. Schools and colleges have become training camps for skilled labor instead of forums for questioning and discussion, and colleges and universities are no longer nurseries for those inquirers whom Francis Bacon, in the sixteenth century, called "merchants of light."9 We teach ourselves to ask "How much will it cost?" and "How long will it take?" instead of "Why?"

"Why?" (in its many variations) is a question far more important in its asking than in the expectation of an answer. The very fact of uttering it opens numberless possibilities, can do away with preconceptions, summons up endless fruitful doubts. It may bring, in its wake, a few tentative answers, but if the question is powerful enough, none of these answers will prove all-sufficient. "Why?," as children intuit, is a question that implicitly places our goal always just beyond the horizon.10

The visible representation of our curiosity—the question mark that stands at the end of a written interrogation in most Western languages, curled over itself against dogmatic pride—arrived late in our histories. In Europe, conventionalized punctuation was not established until the late Renaissance when, in 1566, the grandson of the great Venetian printer Aldo Manutius published his punctuation handbook for typesetters, the Interpun- gendi ratio. Among the signs devised to conclude a paragraph, the handbook included the medieval punctus interrogativus, and Manutius the Younger defined it as a mark that signaled a question which conventionally required an answer. One of the earliest instances of such question marks is in a ninth- century copy of a text by Cicero, now in the Bibliotheque nationale in Paris; it looks like a staircase ascending toward the top right in a squiggly diagonal from a dot at the bottom left. Questioning elevates us.11

Throughout our various histories, the question "Why?" has appeared under many guises and in vastly different contexts. The number of possible questions may seem too great to consider individually in depth and too varied to assemble coherently, and yet some attempts have been made to gather a few according to various criteria. For instance, a list of ten questions that "science must answer" (the "must" protests too much) was drawn up by scientists and philosophers invited by the editors of the Guardian of London in 2010. The questions were: "What is consciousness?" "What happened before

U id^fnf- iAt^ucJ!iomtv-urn fe-ptffime-nef

тоу~ j. i fbj n b iif*fif p j cai"

Example of punctus interrogativus in a ninth-century manuscript of Cicero's Cato maior de senectute. (Paris, Bibliotheque nationale, MS lat. 6332, fol. 81)

the Big Bang?" "Will science and engineering give us back our individuality?" "How are we going to cope with the world's burgeoning population?" "Is there a pattern to the prime numbers?" "Can we make a scientific way of thinking all-pervasive?" "How do we ensure humanity survives and flourishes?" "Can someone explain adequately the meaning of infinite space?" "Will I be able to record my brain like I can record a programme on television?" "Can humanity get to the stars?" There is no evident progression in these questions, no logical hierarchy, no clear evidence that they can be answered. They proceed by branching out from our desire to know, creatively sifting through our acquired wisdom. And yet, a certain shape might be glimpsed in their meandering. In following a necessarily eclectic path through a few of the questions sparked by our curiosity, something like a parallel cartography of our imagination may perhaps become apparent. What we want to know and what we can imagine are the two sides of the same magical page.

One of the common experiences in most reading lives is the discovery, sooner or later, of one book that like no other allows for an exploration of oneself and of the world, that appears to be inexhaustible yet at the same time concentrates the mind on the tiniest particulars in an intimate and singular way. For certain readers, that book is an acknowledged classic, a work by Shakespeare or Proust, for example; for others it is a lesser-known or less agreed- upon text that deeply echoes for inexplicable or secret reasons. In my case, throughout my life, that unique book has changed: for many years it was Montaigne's Essays or Alice in Wonderland, Borges's Ficciones or Don Quixote, the Arabian Nights or The Magic Mountain. Now, as I approach the prescribed three score and ten, the book that is to me all-encompassing is Dante's Commedia.

I came to the Commedia late, just before turning sixty, and from the very first reading, it became for me that utterly personal yet horizonless book. To describe the Commedia as horizonless may be simply a way of declaring a kind of superstitious awe of the work itself: of its profundity, its breadth, its intricate construction. Even these words fall short of my constantly renewed experience of reading the text. Dante spoke of his poem as one "in which lend a hand heaven and earth."12 This is not a hyperbole: it is the impression its readers have had from Dante's age on. But construction implies an artificial mechanism, an act dependent on pulleys and cogs which, even when evident (as in Dante's invention of the terza rima, for instance, and accordingly his use of the number 3 throughout the Commedia), merely points to a speck in the complexity but hardly illuminates its apparent perfection. Giovanni Boccaccio compared the Commedia to a peacock whose body is covered with "angelic" iridescent feathers of countless hues. Jorge Luis Borges compared it to an infinitely detailed engraving, Giuseppe Mazzotta to a universal encyclopedia. Osip Mandelstam had this to say: "If the halls of the Hermitage should suddenly go mad, if the paintings of all schools and masters should suddenly break loose from the nails, should fuse, intermingle, and fill the air of the rooms with futuristic howling and colors in violent agitation, the result then would be something like Dante's Commedia." And yet none of these similes captures entirely the fullness, depth, reach, music, kaleidoscopic imagery, infinite invention, and perfectly balanced structure of the poem. The Russian poet Olga Sedakova has noted that Dante's poem is "art that generates art" and "thought that generates thought" but, more important, it is "experience that generates experience."13

In a parody of twentieth-century artistic currents, from the nouveau roman to conceptual art, Borges and his friend Adolfo Bioy Casares imagined a form of criticism that, surrendering to the impossibility of analyzing a work of art in all its greatness, merely reproduced the work in its entirety.14 Following this logic, in order to explain the Commedia, a meticulous commentator would have to end up quoting the whole poem. Perhaps that is the only way. It is true that when we come across an astonishingly beautiful passage or an intricate poetic argument that had not struck us as forcibly in a previous reading, our impulse is not so much to comment on it as to read it aloud to a friend, in order to share, as far as possible, the original epiphany. To translate the words into other experiences: maybe this is one of the possible meanings of Beatrice's words to Dante in the Heaven of Mars: "Turn around and listen, / because not only in my eyes is Paradise."15

Less ambitious, less knowledgeable, more conscious of my own horizons, I want to offer a few readings of my own, a few comments based on personal reflections, observations, translations into my own experience. The Commedia has a certain majestic generosity that does not bar entry to anyone attempting to cross its threshold. What each reader finds there is another matter.

There is an essential problem with which every writer (and every reader) is faced when engaging with a text. We know that to read is to affirm our belief in language and its vaunted ability to communicate. Every time we open a book, we trust, in spite of all our previous experience, that this once the essence of the text will be conveyed to us. And every time we reach the last page, in spite of such brave hopes, we are again disappointed. Especially when we read what for want of more precise terms we agree to call "great literature," our ability to grasp the text in all its multilayered complexity falls short of our desires and expectations, and we are compelled to return to the text once again in the hope that this time, perhaps, we will achieve our purpose. Fortunately for literature, fortunately for us, we never do. Generations of readers cannot exhaust these books, and the very failure of language to communicate fully lends them a limitless richness that we fathom only to the extent of our individual capabilities. No reader has ever reached the depths of the Mahabharata or the Oresteia.

The realization that a task is impossible does not prevent us from attempting it, and every time a book is opened, every time a page is turned, we renew the hope of understanding a literary text, if not in its entirety, at least a little more than on the previous reading. That is how, throughout the ages, we create a palimpsest of readings that continuously reestablishes the book's authority, always under a different guise. The Iliad of Homer's contemporaries is not our Iliad, but it includes it, as our Iliad includes all Iliads to come. In this sense, the Has- sidic assertion that the Talmud has no first page because every reader has already begun reading it before starting at the first words is true of every great book.16

The term lectura dantis was created to define what has become a specific genre, the reading of the Commedia, and I am fully aware that, after generations of commentaries beginning with those of Dante's own son Pietro, written shortly after his father's death, it is impossible to be either comprehensively critical or thoroughly original in what one has to say about the poem. And yet, one might be able to justify such an exercise by suggesting that every reading is, in the end, less a reflection or translation of the original text than a portrait of the reader, a confession, an act of self-revelation and self-discovery.

The first of these autobiographical readers was Dante himself. Throughout his otherworldly journey, having been told that he must find a new path in life or be lost forever, Dante is seized by an ardent curiosity to know who he truly is and what it is he experiences along the way.17 From the first verse of Inferno to the last verse of Paradiso, the Commedia is marked with Dante's questions.

In the whole of his essays, Montaigne quotes Dante only twice. Scholars are of the opinion that he had not read the Commedia but knew of it through references in the works of other writers. Even if he had read it, possibly Montaigne might not have liked the dogmatic structure within which Dante chose to conduct his explorations. Nevertheless, when discussing the power of speech in animals, Montaigne transcribes three verses from Purgatorio XXVI in which Dante compares the penitent lustful souls to "dark battalions of communicating ants."18 And again he quotes Dante when discussing the education of children. "Let the tutor," says Montaigne, "pass everything through a filter and never lodge anything in the boy's head simply by authority, at second-hand. Let the principles of Aristotle not be principles for him any more than those of the Stoics or the Epicureans. Let this diversity of judgments be set before him; if he can, he will make a choice: if he cannot then he will remain in doubt. Only fools have made up their minds and are certain." Montaigne then quotes the following line of Dante: "Not less than knowing, doubting [dubbiar] pleases me," the words Dante addresses to Virgil in the sixth circle of hell, after the Latin poet has explained to his charge why the sins of incontinence are less offensive to God than those that are the fruit of our will. For Dante, the words express the pleasure felt in the expectant moment that precedes the acquisition of knowledge; for Montaigne, they describe a constant state of rich uncertainty, being aware of various opposing views but embracing none except one's own. For both, the state of questioning is as rewarding as, or even more so than, that of knowing.19

Is it possible, as an atheist, to read Dante (or Montaigne) without believing in the God they worshiped? Is it presumptuous to assume a measure of understanding of their work without the faith that helped them bear the suffering, bewilderment, anguish (and also joy) that are the lot of every human being? Is it insincere to study the strict theological structures and subtleties of religious dogmas without being convinced by the tenets on which they are based? As a reader, I claim the right to believe in the meaning of a story beyond the particulars of the narrative, without swearing to the existence of a fairy godmother or a wicked wolf. Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood don't need to have been real people for me to believe in their truths. The god who walked in the garden "in the cool of the evening" and the god who, agonizing on a cross, promised Paradise to a thief, enlighten me in ways that nothing but great literature can. Without stories all religion would be mere preaching. It is stories that convince us.

The art of reading is in many ways opposed to the art of writing. Reading is a craft that enriches the text conceived by the author, deepening it and rendering it more complex, concentrating it to reflect the reader's personal experience and expanding it to reach the farthest confines of the reader's universe and beyond. Writing, instead, is the art of resignation. The writer must accept the fact that the final text will be but a blurred reflection of the work conceived in the mind, less enlightening, less subtle, less poignant, less precise. The imagination of a writer is all-powerful, and capable of dreaming up the most extraordinary creations in all their wishful perfection. Then comes the descent into language, and in the passage from thought to expression much—very much—is lost. To this rule there are hardly any exceptions. To write a book is to resign oneself to failure, however honorable that failure might be.

Conscious of my hubris, it occurred to me that, following Dante's example of having a guide for his travels—Virgil, Statius, Beatrice, Saint Bernard—I might have Dante himself as a guide to mine, and allow his questioning to help steer my own. Though Dante admonished those who in tiny skiffs attempt to follow his keel, and warned them to turn back to their own shores for fear of becoming lost,20 I nevertheless trust that he will not mind helping out a fellow traveler filled with so much agreeable dubbiar.

1

What Is Curiosity?

Everything begins with a voyage. One day, when I was eight or nine, in Buenos Aires, I lost my way coming back from class. The school was one of many that I attended in my childhood, and stood a short distance from our house, in the tree-lined neighborhood of Belgrano. Then as now, I was easily distracted, and all sorts of things caught my attention as I walked back home in the starched white pinafore all schoolchildren were obliged to wear: the corner grocery store that before the age of supermarkets held large barrels of briny olives, cones of sugar wrapped in light-blue paper, blue tins of Canale biscuits; the stationer's with its patriotic notebooks displaying the faces of our national heroes and shelves lined with the yellow covers of the Robin Hood children's series; a tall, narrow door with harlequin stained glass which was sometimes left open, revealing a grim courtyard where a tailor's mannequin mysteriously languished; the sweet seller, a fat man sitting at a street corner on a tiny stool, who held, like a lance, his kaleidoscopic wares. I usually took the same way back, counting off the landmarks as I passed them, but that day I decided to change course. After a few blocks, I realized I didn't know the way. I was too ashamed to ask for directions, so I wandered, more astonished than frightened, for what seemed to me a very long time.

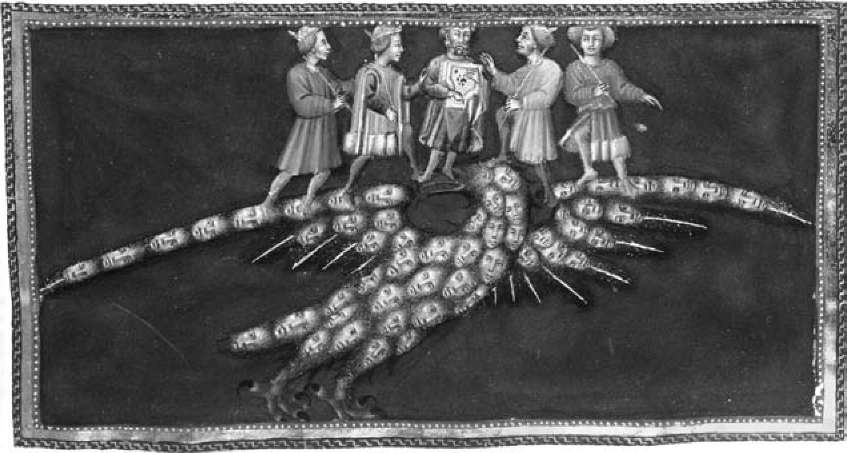

(Opposite) Dante and Virgil meet the sowers ofdiscord. Woodcut illustrating Canto XXVIII of the Inferno, printed in 1487 with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

I don't know why I did what I did, except that I wanted to experience something new, to follow whatever clues I might find to mysteries not yet apparent, as in the Sherlock Holmes stories, which I had just discovered. I wanted to deduce the secret story of the doctor with a battered walking stick, to reveal that the tiptoeing footmarks in the mud were those of a man running for his life, to ask myself why someone would be wearing a groomed black beard that was no doubt false. "The world is full of obvious things which nobody by any chance ever observes," said the Master.

I remember becoming aware, with a feeling of pleasurable anxiety, that I was engaging in an adventure different from the ones on my shelves and yet I experienced something of the same suspense, the same intense desire to find out what lay ahead, without being able (without wanting) to foretell what might take place. I felt as if I'd entered a book and was on the way to its undisclosed final pages. What exactly was I looking for? Perhaps this was when for the first time I conceived of the future as a place that held together the tail-ends of all the possible stories.

But nothing happened. At long last, I turned a corner and found myself on familiar ground. When I finally saw my house, it felt like a disappointment.

But we hold several threads in our hands, and the odds are that one or other of them guides us to the truth. We may waste time following the wrong one, but sooner or later, we must come upon the right.

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, "The Hound of the Baskervilles"

C

uriosity is a word with a double meaning. The etymological Spanish dictionary of Covarrubias of 1611 defines curioso (it is the same in Italian) as a person who treats something with particular care and diligence, and the great Spanish lexicographer explains its derivation curio- sidad (in Italian, curiositti) as resulting because "the curious person is always asking: 'Why this and why that?'" Roger Chartier has noted that these first definitions did not satisfy Covarrubias, and in a supplement written in 1611 and 1612 (and left unpublished) Covarrubias added that curioso has "both a positive and a negative sense. Positive, because the curious person treats things diligently; and negative, because the person labors to scrutinize things that are most hidden and reserved, and do not matter." There follows a quotation in Latin from one of the apocryphal books of the Bible, Ecclesiasticus: "Do not try to understand things that are too difficult for you, or try to discover what is beyond your powers" (3:21-22). With this, according to Chartier, Covarrubias opens his definition to the biblical and patristic condemnation of curiosity as the illicit yearning to know what is forbidden.1 Of this ambiguous nature of curiosity, Dante was certainly aware.

Dante composed almost all, if not all, of the Commedia while in exile, and the account of his poetic pilgrimage can be read as a hopeful mirror of his forced pilgrimage on earth. Curiosity drives him, in Covarrubias's sense of treating things "diligently," but also in the sense of seeking to know what is "most hidden and reserved" and lies beyond words. In a dialogue with his otherworldly guides (Beatrice, Virgil, Saint Bernard) and with the damned and blessed souls he encounters, Dante allows his curiosity to lead him on towards the ineffable goal. Language is the instrument of his curiosity—even as he tells us that the answer to his most burning questions cannot be uttered by a human tongue—and his language can be also the instrument of ours. Dante can act, in our reading of the Commedia, as a "midwife" of our thoughts, as Socrates once defined the role of the seeker of knowledge.2 The Commedia allows us to bring our questions into being.

Dante died in exile in Ravenna on 13 or 14 September 1321, after having recorded in the last verses of his Commedia his vision of the everlasting light of God. He was fifty-six years old. According to Giovanni Boccaccio, Dante had begun writing the Commedia sometime before his banishment from Florence, and had been forced to abandon in the city the first seven cantos of the Inferno. Someone, Boccaccio says, searching for a document among the papers in Dante's house, found the cantos without knowing they were by Dante, read them with admiration, and took them for inspection to a Florentine poet "of some renown," who guessed that they were Dante's work and contrived to send them on to him. Always according to Boccaccio, Dante was at the time at the estate of Moroello Malaspina in Lunigiana; Malaspina received the cantos, read them, and begged Dante not to abandon a work so magnificently begun. Dante consented and began the eighth canto of the Inferno with the words: "I say, carrying on, that long before . . ." So goes the story.3

Extraordinary literary works seem to demand extraordinary tales of their conception. Magical biographies of a phantom Homer were invented to account for the power of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Virgil was lent the gifts of a necromancer and herald of Christianity because, his readers thought, the Aeneid could not have been composed by an ordinary man. Consequently, the conclusion of a masterpiece must be even more extraordinary than its inception. As the writing of the Commedia advanced, Boccaccio tells us, Dante began to send the completed cantos to one of his patrons, Cangrande della Scala, in lots of six or eight. In the end, Cangrande would have received the entire work with the exception of the last thirteen cantos of Paradiso. For the months following Dante's death, his sons and disciples searched among his papers to see if he had not perhaps finished the missing cantos. Finding nothing, says Boccaccio, "they were enraged that God had not allowed him to live

The first portrait of Dante to appear in a printed book. Hand-colored woodcut in Lo amoroso Convivio di Dante (Venice, 1521). (Photograph courtesy of Livio Ambrogio. Reproduced by permission.)

in the world long enough to have the chance of concluding what little remained of his work." One night, Jacopo, Dante's third son, had a dream. He saw his father approach, dressed in a white gown, his face shining with a strange light. Jacopo asked him if he was still alive, and Dante said that he was, but in the true life, not in ours. Jacopo then asked whether he had finished his Commedia. "Yes," was the answer, "I finished it," and he led Jacopo to his old bedroom, where, putting his hand on a certain place on the wall, he announced, "Here is what you were searching for for so long." Jacopo woke, fetched an old disciple of Dante's, and together they discovered, behind a hanging cloth, a recess containing moldy writings which proved to be the missing cantos. They copied them out and sent them, according to Dante's habit, to Cangrande. "Thus," Boccaccio tells us, "was the task of so many years brought to its conclusion."4

Boccaccio's story, which today is regarded less as factual history than as an admiring legend, lends the creation of what is perhaps the greatest poem ever penned an appropriately magical frame. And yet neither the initial suspense- ful interruption nor the final happy revelation suffice, in the reader's mind, to account for the invention of such a work. The history of literature is rich in stories about desperate situations in which writers have managed to create masterpieces. Ovid dreaming his Tristia in the hellhole of Toomis, Boethius writing his Consolation of Philosophy in prison, Keats composing his great odes while dying of tubercular fever, Kafka scribbling his Metamorphosis in the public corridor of his parents' house contradict the assumption that a writer can write only under auspicious circumstances. Dante's case is, however, particular.

In the late thirteenth century, Tuscany was split into two political factions: the Guelphs, loyal to the pope, and the Ghibellines, loyal to the imperial cause. In 1260, the Ghibellines defeated the Guelphs at the Battle of Montaperti; a few years later, the Guelphs began to regain their lost power, eventually expelling the Ghibellines from Florence. By 1270 the city was entirely Guelph and would remain so throughout Dante's lifetime. Shortly after Dante's birth in 1265, the Guelphs of Florence divided into the Blacks and the Whites, this time along family rather than political lines. On 7 May 1300, Dante took part in an embassy to San Gimigniano on behalf of the ruling White faction; a month later he was elected one of the six priors of Florence. Dante, who believed that church and state should not interfere in one another's spheres of action, opposed the political ambitions of Pope Boniface VIII; consequently, when he was sent to Rome in the autumn of 1301 as part of the Florentine embassy, Dante was ordered to stay at the papal court while the other ambassadors returned to Florence. On 1 November, in Dante's absence, the landless French prince Charles de Valois (whom Dante despised as an agent of Boniface) entered Florence, supposedly to restore peace but in fact to allow a group of exiled Blacks to enter the city. Led by their chief, Corso Donati, for five days the Blacks pillaged Florence and murdered many of its citizens, driving the surviving Whites into exile. In time, the exiled Whites became identified with the Ghibelline faction, and a Black priorate was installed to rule Florence. In January 1302, Dante, who was probably still in Rome, was condemned to exile by the priorate. Later, when he refused to pay the fine imposed as penalty, his sentence of two years' exile was changed to that of being burned at the stake if he ever returned to Florence. All his goods were confiscated.

Dante's exile took him first to Forli, then, in 1303, to Verona, where he stayed until the death of the city's lord, Bartolomeo della Scala, on 7 March 1304. Because the new ruler of Verona, Alboino della Scala, was unfriendly, or because Dante thought he could enlist the sympathies of the new pope, Benedict XI, the exile returned to Tuscany, probably to Arezzo. For the next few years his itinerary is uncertain—perhaps he moved to Treviso, but Luni- giana, Lucca, Padua, and Venice are also possible halting places; in 1309 or 1310 he may have visited Paris. In 1312, Dante returned to Verona. Cangrande della Scala had become, a year earlier, the city's sole ruler, and thereafter Dante lived in Verona under his protection, until at least 1317. Dante's final years were spent in Ravenna, at the court of Guido Novelo da Polenta.

In the absence of irrefutable documentary evidence, scholars suggest that Dante began the Inferno either in 1304 or 1306, the Purgatorio in 1313, and the Paradiso in 1316. The exact dating matters less than the astonishing fact that Dante wrote the Commedia during almost twenty years of wandering in more than ten alien cities, away from his library, his desk, his papers, his talismans—the superstitious bric-a-brac with which every writer constructs a working theater. In unfamiliar rooms, amidst people to whom he owed polite gratitude, in spaces that, because they were not his intimate own, must have seemed relentlessly public, always subject to social niceties and the conventions of others, it must have been a daily struggle to find small moments of privacy and silence in which to work. Since his own books were not available, with his annotations and remarks scribbled on the margins, his main recourse was the library of his mind, marvelously furnished (as the countless literary, scientific, theological, and philosophical references in the Commedia show) but subject, like all such libraries, to the depletions and blurrings that come with age.

What were his first attempts like? In a document preserved by Boccaccio, a certain Brother Ilario, "a humble monk of Corvo," says that one day a traveler came to his monastery. Brother Ilario recognized him, "for though I had never once seen him before that day, his fame had long before reached me." Perceiving the monk's interest, the traveler "drew a little book from his bosom in a friendly enough way" and showed him some verses. The traveler, of course, was Dante; the verses, the initial cantos of the Inferno, which, though written in the vernacular of Florence, Dante tells the monk he had at first intended to write in Latin.5 If Boccaccio's document is authentic, then Dante had managed to take with him into exile the first few pages of his poem. It would have been enough.

We know that early on in his travels, Dante had begun to send friends and patrons copies of a few of the cantos, which were then often copied and passed along to other readers. In August 1313, the poet Cino da Pistoia, one of Dante's friends in the early years, included glosses of a few verses from two cantos of the Inferno in a song he wrote on the death of the emperor Henry VII; in 1314 or perhaps somewhat earlier, a Tuscan notary, Francesco da Bar- berino, mentions the Commedia in his Documenti d'amore. There are several other proofs that Dante's work was known and admired (and envied and scorned) long before the Commedias completion. Barely twenty years after Dante's death, Petrarch mentions how illiterate artists recited parts of the poem at crossroads and theaters to applauding drapers, innkeepers, and customers in shops and markets.6 Cino, and later Cangrande, must have had an almost complete manuscript of the poem, and we know that Dante's son Jacopo worked from a holograph copy to produce a one-volume Commedia for Guido da Polenta. Today not a single line in Dante's hand has come down to us. Coluccio Salutati, an erudite Florentine humanist who translated parts of the Commedia into Latin, recalled seeing Dante's "lean script" in some of his now lost epistles in the Chancery of Florence, but we can only imagine what his handwriting looked like.7

How the notion of writing the chronicle of a journey to the Otherworld came to Dante is, of course, an unanswerable question. A clue may lie at the end of his Vita nova, an autobiographical essay structured around thirty-one lyric poems whose meaning, purpose, and origin Dante attributes to his love for Beatrice: in the last chapter, Dante speaks of an "admirable vision" which makes him resolve to write "what has never been written of any other woman." A second explanation may be the fascination felt for popular tales of otherworldly journeys among Dante's contemporaries. In the thirteenth century these imaginary voyages had become a thriving literary genre, born perhaps from anxieties to know what lies beyond the last breath: to revisit the departed and learn whether they require the weak hold of our memory for their continued existence, to find out whether our actions on this side of the grave have consequences on the other. Such questions, of course, were not new even then: ever since we started telling stories, in the days before history, we began to draw up a detailed geography for the regions of the Otherworld. Dante would have been familiar with a number of these travelogues. Homer, for instance, allowed Odysseus to visit the Land of the Dead on his delayed return to Ithaca; Dante, who had no Greek, knew the version of that descent given by Virgil in his Aeneid. Saint Paul, in his Second Epistle to the Corinthians, wrote of a man who had been to Paradise and "heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter" (12:4). When Virgil appears to Dante and tells him that he will lead him "through an eternal place," Dante acquiesces, but then hesitates.

But why should I go? And who allows it?

I am not Aeneas, nor am I Paul.8

Dante's audience would have understood the references.

Dante, voracious reader, would have also been familiar with Cicero's Scipio's Dream and its description of the celestial spheres, as well as with the otherworldly incidents in Ovid's Metamorphoses. Christian eschatology would have provided him with several more accounts. In the Apocryphal Gospels, the so-called Apocalypse of Peter describes the saint's vision of the Holy Fathers wandering in a perfumed garden, and the Apocalypse of Paul speaks of a fathomless abyss into which the souls of those who did not hope for God's mercy are flung.9 Other journeys and visions appear in such best-selling pious compendia as Jacop de Voragine's Golden Legend and the anonymous Lives of the Fathers; in the imaginary Irish travel narratives of Saint Brendan, Saint Patrick, and King Tungdal; in the mystic visions of Peter Damian, Richard de Saint-Victoire, and Gioachim de Fiore; and in certain Islamic Otherworld chronicles, such as the Andalucian Libro della Scala (Book of the Ladder), which tells of Muhammad's ascent to heaven. (We will return to this Islamic influence on the Commedia farther on.) There are always models for any new literary venture: our libraries repeatedly remind us that there is no such thing as literary originality.

The earliest verses Dante wrote were, as far as we know, several poems composed in 1283, when he was eighteen years old, later included in the Vita nova; the last work was a lecture in Latin, QQuestio de aqua et terra (Dispute on Earth and Water), which he delivered in a public reading on 20 January 1320, less than two years before his death.

The Vita nova was finished before 1294: its declared intention is to clarify the words Incipit Vita Nova, "Here Begins the New Life," inscribed in the "volume of my memory," and following the sequence of poems written for love of Beatrice, whom he saw for the first time when both were children, Dante nine and Beatrice eight. The book is presented as a quest, an attempt to answer the questions elicited by the love poems, driven by a curiosity bred, Dante says, in "the high chamber where all the sensitive spirits carry their perceptions."10

Dante's last composition, the Questio de aqua et terra, is a philosophical inquiry into several scientific matters, following the style of "disputes" popular at the time. In his introduction, Dante writes: "Therefore, nourished as I have been since my childhood with the love of truth, I suffered not to leave myself out of the debate, but chose to show what was true therein, and also to dissolve all contrary arguments, as much for love of truth as for hatred of falsity."11 Between the first mention of a need for questioning and the last lies the vast territory of Dante's masterwork. The entire Commedia can be read as the pursuit of one man's curiosity.

According to patristic tradition, curiosity can be of two kinds: the curiosity associated with the vanitas of Babel, which leads us to believe ourselves capable of such feats as building a tower to reach the heavens; and the curiosity of umilth, of thirsting to know as much as we can of the divine truth, so that, as Saint Bernard prays for Dante in the Commedias last canto, "joy supreme may be unfolded to him." Quoting Pythagoras in his Convivio, Dante defined a person who pursues this wholesome curiosity precisely as a "lover of knowledge . . . a term not of arrogance but of humility."12

Though scholars such as Bonaventure, Siger de Brabant, and Boethius deeply influenced Dante's thought, Thomas Aquinas, above all, was Dante's maitre h penser: as Dante's Commedia is to his curious readers, Aquinas's writings were to Dante. When Dante, guided by Beatrice, reaches the Heaven of the Sun, where the prudent are rewarded, a crown of twelve blessed souls circle around him three times to the sound of a celestial music, until one of them detaches itself from the dance and speaks to him. It is the soul of Aquinas, which tells him that, since true love has at last been kindled in Dante, Aquinas and the other blessed souls must answer his questions out of that same love. According to Aquinas, and following the teachings of Aristotle, the knowledge of the supreme good is such that once perceived it can never be forgotten, and the soul blessed with such knowledge will always yearn to return to it. What Aquinas calls Dante's "thirst" must inevitably be satisfied: it would be as impossible not to try to assuage it "as it is for water not to flow back to the sea."13

Aquinas was born in Roccasecca, in the Kingdom of Sicily, heir to a noble family related to much of the European aristocracy: the Holy Roman emperor was his cousin. At the age of five, he began his studies at the celebrated Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino. He must have been an insufferable child: it is told that after remaining silent in class for many days, his first utterance to his teacher was a question, "What is God?"14 At fourteen, his parents, wary of political divisions in the abbey, transferred him to the recently founded University of Naples, where he began his lifelong study of Aristotle and his commentators. During his university years, around 1244, he decided to join the Dominican order. Aquinas's choice to become a Dominican mendicant friar scandalized his aristocratic family. They had him kidnapped and held confined for a year, hoping he would recant. He did not, and once set free he settled for a time in Cologne to study under the celebrated teacher Albertus Magnus. For the rest of his life he taught, preached, and wrote in Italy and France.

Aquinas was a large man, clumsy and slow, characteristics that earned him the nickname "Dumb Ox." He refused all positions of power and prestige, whether that of courtier or abbot. He was, above all, a lover of books and reading. When asked for what he thanked God most, he answered, "for granting me the gift of understanding every page I've ever read."15 He believed in reason as a means of attaining the truth, and constructed, along Aristotelian philosophy, laborious logical arguments to reach some measure of conclusion to the great theological questions. For this he was condemned, three years after his death, by the bishop of Paris, who maintained that the absolute power of God could do without any quibbles of Greek logic.

Aquinas's major work is the Summa Theologica, a vast survey of the principal theological questions, intended, he says in the prologue, "not only to teach the proficient, but also to instruct beginners."16 Aware of the need for a clear and systematic presentation of Christian thought, Aquinas made use of the recently recovered works of Aristotle, translated into Latin, to construct an intellectual framework that would support the sometimes contradictory fundamental Christian canonical writings, from the Bible and the books of Saint Augustine to the works of the theologians of his own time. Aquinas was still writing the Summa a few months before his death in 1274. Dante, who was only nine when Aquinas died, may have met some of the master's disciples at the University of Paris if (as legend has it) he visited the city as a young man. Whether through the teachings of Aquinas's followers or his own readings, Dante certainly knew and made use of Aquinas's theological cartography, much as he knew and made use of Augustine's invention of the first-person protagonist to recount his life's journey. And certainly he knew both their arguments concerning the nature of human inquisitiveness.

The beginning point of all quests is, for Aquinas, Aristotle's celebrated statement "All human beings, by nature, desire to know," to which Aquinas refers several times in his writings. Aquinas proposed three arguments for this desire. The first is that each thing naturally desires its perfection, that is to say, to become fully conscious of its nature and not merely capable of achieving this consciousness; this, in human beings, means acquiring a knowledge of reality. Second, that everything inclines to its proper activity: as fire to heating and heavy things to falling, humans are inclined to understanding, and consequently to knowing. Third, everything desires to be united to its principal— the end to its beginning—in that most perfect of motions, that of the circle; it is only through intellect that this desire is achieved, and through intellect we each become united to our separate substances. Therefore, Aquinas concludes, all systematic scientific knowledge is good.17

Aquinas remarks that Saint Augustine, in a sort of appendix of corrections to much of his work titled Retractions, observed that "more things are sought than found, and of the things that are found, fewer still are confirmed." This, for Augustine, was a statement of limits. Aquinas, quoting from another work by the prolific Augustine, remarked that the author of the Confessions had warned that allowing our curiosity to inquire about everything in the world might result in the sin of pride and thereby contaminate the authentic pursuit of truth. "So great a pride is thus begotten," Augustine had written, "that one would think they dwelt in the very heavens about which they argue."18 Dante, knowing himself guilty of the sin of pride (the sin for which, he is told, he will return to Purgatory after his death), may have had this passage in mind when visiting the heavens in Paradiso.

Aquinas took Augustine's concern farther, arguing that pride is only the first of four possible perversions of human curiosity. The second entails the pursuit of lesser matters, such as reading popular literature or studying with unworthy teachers.19 The third occurs when we study the things of this world without reference to the Creator. The fourth and last, when we study what is beyond the limits of our individual intelligence. Aquinas condemns these species of curiosity only because they distract from the greater, fuller impulse of natural exploration. In this, he echoes Bernard of Clairvaux, who a century earlier had written: "There are people who want to know solely for the sake of knowing, and that is scandalous curiosity." Four centuries before Clairvaux, Alcuin of York, more generously, defined curiosity in these terms: "As regards wisdom, you love it for the sake of God, for the sake of purity of soul, for the sake of knowing truth, and even for its own sake."20

Like a reverse law of gravity, curiosity causes our experience of the world and of ourselves to increase with the asking: curiosity helps us grow. For Dante, following Aquinas, following Aristotle, what draws us on is a desire for the good or the apparent good, that is to say, towards what we know is good or appears to us to be good. Something in our capacity to imagine reveals to us that something is good, and something in our ability to question propels us towards that something through an intuition of its usefulness or danger. In other cases, we aim towards that ineffable good simply because we don't understand something and demand a reason for it, as we demand a reason for everything in this unreasonable universe. (In my own case, these experiences come often through reading—for instance, wondering with Dr. Watson about the meaning of a candle burning in the moors on a pitch-dark night, or asking with the Master why one of Sir Henry Baskerville's new boots was stolen from the Northumberland Hotel.)

As in an archetypal mystery, achieving the good is always an ongoing search, because the satisfaction of one answer merely leads to asking another question, and so on into infinity. For the believer, the good is equivalent to the godhead: saints reach it when they no longer seek anything. In Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism, this is the state of moksha, or nirvana, of "being blown out" (like a candle) and it refers, in the Buddhist context, to the imperturbable stillness of mind after the fires of desire, aversion, and delusion have been extinguished, the achievement of ineffable beatitude. In Dante, as the great nineteenth-century critic Bruno Nardi defined it, this "end of the quest" is "the state of tranquility in which desire has subsided," that is to say, "the perfect accord of human will with divine will."21 Desire for knowledge, or natural curiosity, is the inquisitive force that impels Dante from within, just as Virgil and, later, Beatrice are the inquisitive forces that lead him onwards from without. Dante allows himself to be led, inside and out, until he no longer requires any of them—not the intimate desire or the illustrious poet or the blessed beloved—as he stands confronted at long last with the supreme divine vision before which imagination and words fall short, as he tells us in the Commedia's famous ending:

To the high fantasy here all power failed; But already my desire and my will were turned Just like a wheel in even measure turned By love that moves the sun and the other stars.22

Common readers (unlike historians) care little for the strictures of official chronology, and find sequences and dialogues across the ages and cultural borders. Four centuries after Dante's high peregrinations, in the British isles a very curious Scotsman imagined a system, "plan'd before [he] was one and twenty, & compos'd before twenty five," that would allow him to set out in writing questions that arose from his brief experience of the world.23 He called his book A Treatise of Human Nature.

David Hume was born in Edinburgh in 1711 and died in 1776. He studied at Edinburgh University, where he discovered the "new Scene of Thought" of Isaac Newton and an "experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects" by which truth might be established. Though his family wished him to follow the career of law, he found "an insurmountable Aversion to every thing but the pursuits of Philosophy and general Learning; and while they fancyed I was pouring over Voet and Vinnius, Cicero and Virgil were the Authors which I was secretly devouring."24

When the Treatise was published in 1739, the reviews were mostly hostile. "Never literary Attempt was more unfortunate than my Treatise of human Nature," he recalled decades later. "It fell dead-born from the Press, without reaching such distinction as even to excite a Murmur among the Zealots."25 The Treatise of Human Nature is an extraordinary profession of faith in the capacity of the rational mind to make sense of the world: Isaiah Berlin, in 1956, would say of its author that "no man has influenced the history of philosophy to a deeper and more disturbing degree." Decrying that in philosophical disputes "'tis not reason, which carries the prize, but eloquence," Hume eloquently proceeded to interrogate the assertions of metaphysicians and theologians, and to inquire as to the meaning of curiosity itself. Prior to experience, Hume argued, anything may be the cause of anything: it is experience and not the abstractions of reason which helps us understand life. Hume's apparent skepticism, however, does not reject all possibility of knowledge: "Nature is too strong for the stupor attendant on the total suspension of belief."26 The experience of the natural world, according to Hume, must direct, mold and ground all our inquiries.

At the end of the second book of his Treatise, Hume attempted to distinguish between love of knowledge and natural curiosity. The latter, Hume wrote, derived from "a quite different principle." Bright ideas enliven the senses and provoke more or less the same sensation of pleasure as "a moderate passion." But doubt causes "a variation of thought," transporting us suddenly from one idea to another. This, Hume concluded, "must of consequence be the occasion of pain." Perhaps unwittingly echoing the previously quoted passage of Ecclesiasticus, Hume insisted that not every fact elicits our curiosity, but occasionally one will become sufficiently important, "if the idea strikes on us with such force, and concerns us so nearly, as to give us an uneasiness in its instability and inconstancy." Aquinas, whose concept of causality raised serious objections in Hume regarding its cogency, had made the same distinction when he had said that "studiousness is directly, not about knowledge itself, but about the desire and study in the pursuit of knowledge."27

This keenness to know the truth, this "love of truth" as Hume calls it, has in fact the same double nature that we saw defined in curiosity itself. "Truth," Hume wrote, "is of two kinds, consisting either in the discovery of the proportions of ideas, consider'd as such, or in the conformity of our ideas of objects to their real existence. 'Tis certain, that the former species of truth, is not desir'd merely as truth, and that 'tis not the justness of our conclusions, which alone gives us pleasure." Pursuit alone of the truth is, for Hume, not enough. "But beside the action of the mind, which is the principal foundation of the pleasure, there is likewise requir'd a degree of success in the attainment of the end, or the discovery of that truth we examine."28

Barely ten years after Hume's Treatise, Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d'Alembert began in France the publication of their Encyclopedie. Here, Hume's definition of curiosity, explained in terms of its outcome, was cleverly reversed: the sources of the impulse, rather than its goals, were explained as "a desire to clarify, to extend one's understanding" and "not particular to the soul itself, belonging to it from its start, independent of sense, as some persons have imagined." The author of the article, the chevalier de Jaucourt, approvingly referred in it to "certain judicious philosophers" who have defined curiosity as "an affection of the soul brought on by sensations or perceptions of objects that we know but imperfectly." That is to say, for the encyclopedistes, curiosity is born from the awareness of our own ignorance and prompts us to acquire, so far as possible, "a more exact and fuller knowledge of the object it represents": something like seeing the outside of a watch and wanting to know what makes it tick.29 "How?" is in this case a form of asking "Why?"

The encyclopedistes translated what for Dante were questions of causality, dependent on divine wisdom, into questions of functionality, dependent on human experience. Hume's proposed examination of the "discovery of truth" meant, for someone like Jaucourt, understanding how things worked in practical, even mechanical terms. Dante was interested in the impulse of curiosity itself, the process of questioning that led us to an affirmation of our identity as human beings, necessarily drawn to the Supreme Good. Stemming from an awareness of our ignorance and tending towards the (wishful) reward of knowledge, curiosity in all its forms is depicted in the Commedia as the means of advancing from what we don't know to what we don't yet know, through a tangle of philosophical, social, physiological, and ethical obstacles, which the pilgrim has to surmount by willingly making the right choices.

One particular example in the Commedia richly illustrates, I believe, the complexity of this multifaceted curiosity. As Dante, led by Virgil, is about to leave the ninth ditch of the eighth circle of Hell, where the sowers of discord are punished, an unexplained curiosity draws his gaze back to the obscene spectacle of the sinners who, because of the rifts they caused during their lifetime, are now themselves slashed, beheaded, or cloven. The last spirit who speaks there to Dante is the poet Bertran de Born, holding up by the hair his severed head "like a lantern."

Because I parted persons who were united I carry, alas, my own brain parted From its source which is this trunk of mine.30

At the sight, Dante weeps, but Virgil reproaches him severely, telling him that he has not grieved as they passed through other ditches of the eighth circle, and nothing warrants his increased attention here. Dante then, almost for the first time, challenges his spirit guide and says to him that had Virgil paid more attention to the cause of his curiosity, he might have allowed Dante to stay longer, because there among the crowd of sinners he thinks he has seen one of his kinsman, Geri del Bello, murdered by a member of another Florentine family and never avenged. This is why, Dante adds, he supposes that Geri turned away without saying a word to him. God's justice must not be questioned, and private revenge is contrary to the Christian doctrine of forgiveness. With this, Dante intends to justify his curiosity.

So where do Dante's tears come from? From pity for the tortured soul of Bertran or from shame at having been given a cold shoulder by Geri? Has his curiosity been prompted by the arrogance of assuming to know better than God himself what is just, by a base passion deviant of his quest for the good, by sympathy for his own unavenged blood, by nothing more than wounded pride? Boccaccio, whose intuition of the sense behind the story is often very keen, noted that the compassion Dante feels at times during the journey is not so much for the souls whose woes he hears but for himself.31 Dante does not provide the answer.

But earlier on he had addressed the reader:

Reader, if God allows you to profit From your reading, now think for yourself How I could keep my face dry.32

Virgil does not respond to Dante's challenge but leads him on to the edge of the next chasm, the last before the core of Hell, where falsifiers are punished with an affliction similar to dropsy: fluid accumulates in their cavities and tissues, and they suffer from a burning thirst. The body of one of the sinners, the coin forger Master Adam, is "shaped like a lute," in a grotesque parody of Christ's crucifixion, which, in medieval iconography, was compared to a stringed instrument.33 Another sinner, burning with fever, is the Greek Sinon, who in the second book of the Aeneid,, allows himself to be captured by the Trojans and then persuades them to take in the Trojan Horse. Sinon, perhaps taking offense at being named, hits Master Adam in his swollen belly, and the two begin a quarrel to which Dante attends enraptured. It is then that Virgil, as if he had been waiting for an opportunity for summing up his reproof, chides him angrily:

Just keep looking A little longer and it is with you that I will quarrel!

Dante is so overwhelmed with shame that Virgil excuses him and concludes: "the desire to listen to such things is a vulgar desire."34 That is to say, fruitless. Not all curiosity leads us on. And yet . . .

"Nature gave us an innate curiosity and, aware of its own art and beauty, created us in order to be the audience of the wonderful spectacle of the world; because it would have toiled in vain, if things so great, so brilliant, so delicately traced, so splendid and variously beautiful, were displayed to an empty house," wrote Seneca in praise of curiosity.35

The great quest which begins in the middle of the journey of our life and ends with the vision of a truth that cannot be put into words is fraught with endless distractions, side paths, recollections, intellectual and material obstacles, and dangerous errors, as well as with errors that, for all their appearance of falsity, are true. Concentration or distraction, asking in order to know why or in order to know how, questioning within the limits of what a society considers permissible or seeking answers outside those limits: these dichotomies, always latent in the phenomenon of curiosity, simultaneously hamper and drive forward every one of our quests. What persists, however, even when we surrender to insurmountable obstacles, and even when we fail in spite of enduring courage and best intentions, is the impulse to seek, as Dante tells us (and Hume intuited). Is this perhaps why, of all the possible modes offered to us by our language, the natural one is the interrogative?

2

What Do We Want to Know?

Most of my childhood in Tel Aviv was spent in silence: I hardly ever asked questions. Not that I wasn't curious. Of course I wanted to find out what was kept locked away in my governess's pyrographed box next to her bed or who lived in the curtained trailers stranded on the beach of Herzliya, where I was sternly warned never to wander. My governess would respond to any questions carefully, after what seemed to me unnecessarily long consideration, and her answers were always short, factual, disallowing argument or discussion. When I wanted to know how the sand was made, her answer was "of shells and stones." When I sought out information on the dreadful Erlkonig of Goethe's poem, which I had to learn by heart, the explanation was "It's only a nightmare." (Because the German word for nightmare is Al- pentraum, I imagined that bad dreams could take place only in the mountains.) When I wondered why it was so dark at night and so light during the day, she drew a series of dotted circles on a piece of paper, meant to represent the solar system, and then made me memorize the names of the planets. She never refused to answer and she never encouraged questioning.

It wasn't until much later that I discovered that questioning might be

(Opposite) Dante and Virgil meet the evil counselors punished by fire.

Woodcut illustrating Canto XXVI of the Purgatorio, printed in 1487 with commentary by Cristoforo Landino. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library,

Yale University)

something else, akin to the thrill of a quest, the promise of something that shaped itself in the making, a progression of explorations that grew in a mutual exchange between two people and did not require a conclusion. It is impossible to stress the importance of having the freedom of such inquiries. To a child, they are as essential to the mind as movement is to the physical body. In the seventeenth century Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that a school had to be a space where the imagination and reflection were given free range, without any obvious practical purpose or utilitarian goal. "The civil man is born, lives, and dies in slavery," he wrote. "At his birth he is sewn into swaddling clothes; at his death he is nailed into a coffin. As long as he retains a human form, he is chained up by our institutions." It is not by training our children to go into whatever trade society requires, Rousseau insisted, that they will become efficient in their tasks. They have to be able to imagine with no constraints before they can bring anything truly valuable into being.

One day, a new history teacher began his class by asking us what we wanted to know. Did he mean what we wanted to know? Yes. About what? About anything, any notion that occurred to us, anything we wished to ask. After a startled silence, someone lifted his hand and posed a question. I don't remember what it was (a distance of more than half a century separates me from that brave inquisitor), but I do remember that the teacher's first words were less an answer than the hint of another question. Maybe we began by wanting to know what made a motor run; we ended by wondering how Hannibal had managed to cross the Alps, what gave him the idea of using vinegar to split the frozen rocks, what an elephant might have felt falling to its death in the snow. That night each of us dreamt his own secret Alpentraum.

Ulysses: Know the whole world. —Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, 2.3.246

he interrogative mode carries with it the expectation, not always fulfilled, of an answer: however uncertain, it is the prime instrument of curiosity. The tension between the curiosity that leads to discov-

ery and the curiosity that leads to perdition threads its way throughout all our endeavors. The temptation of the horizon is always present, and even if, as the ancients believed, after the world's end a traveler would fall into the abyss, we do not abstain from exploration, as Ulysses tells Dante in the Commedia.

In the twenty-sixth canto of the Inferno, after having crossed the dreadful snake-infested sands where thieves are punished, Dante arrives at the eighth chasm, where he sees "as many fireflies as the peasant, resting on a hilltop, sees": they are souls who are punished here, eternally consumed in whirling tongues of fire. Curious to know what one particular flame is "that comes so parted at the top," Dante learns that these are the entwined souls of Ulysses and his companion Diomedes (who, according to post-Homeric legend, had helped Ulysses steal the Palladium, the sacred image of Athena on which the fortunes of Troy depended). Dante is so attracted to the horned flame that his body leans involuntarily towards it and he asks Virgil's permission to address the fiery presence. Virgil, realizing that, as Greeks, the ardent spirits may disdain to speak to a mere Florentine, speaks to the flame as a poet who "when on earth wrote lofty verses" and begs that one of the two souls will tell where they met their end. The larger tongue of the flame responds and reveals itself as Ulysses, whose words, legend has it, could bend the will of his listeners. Then the epic hero whose adventures were the source of Virgil's Aeneid (Ulysses left the sorceress Circe at the island of Gaeta, he says, "before Aeneas gave that place its name") speaks to the poet he inspired. In Dante's universe, creators and creations construct their own chronologies.1

The character of Ulysses can be seen in the Commedia partly as the incarnation of forbidden curiosity, but he begins life on our shelves (though he may be older than his stories) as Homer's ingenious and persecuted King Odysseus. Then, through a series of complex reincarnations, he becomes a cruel commander, a faithful husband, a lying con man, a humanist hero, a resourceful adventurer, a dangerous magician, a ruffian, a trickster, a man in search of his identity, Joyce's pathetic Everyman. Dante's version of the Ulysses story, which is now part of the myth, concerns a man not satisfied with the extraordinary life he has led: he wants more. Unlike Faust, who despairs at how little his books have taught him and feels he has at last reached the limits of his library, Ulysses longs for that which lies beyond the end of the known world. After being freed from Circe's island and Circe's lust, Ulysses senses that there is in him something stronger than his love for his abandoned son, his aged father, his faithful wife back in Ithaca: an ardore, or "ardent passion," to gain further experience of the world, and of human vices and virtues. In the course of only fifty-two luminous lines, Ulysses will try to explain the reasons that drove him to undertake his last journey: the desire to go beyond the signposts Hercules set up to signal the limits of the known world and warn humans against sailing farther, the will not to deny himself the experience of the unpeopled world behind the sun, and finally, the longing to pursue virtue and wisdom—or, as Tennyson put it in his version, "to follow knowledge like a sinking star, / Beyond the utmost bound of human thought."2

The columns that signal the limits of the knowable world are also, as all professed limits, a challenge to the adventurer. Three centuries after the Commedia was completed, Torquato Tasso, a devoted reader of Dante, in his Gerusalemme liberata had the goddess Fortune lead the comrades of the unfortunate Rinaldo (who must be rescued before Jerusalem can be reconquered) along Ulysses' path up to the Pillars of Hercules. There an infinite sea stretches out beyond, and one of the comrades asks whether anyone has dared cross it. Fortune answers that Hercules himself, not daring to venture out onto the unknown main, "set up narrow limits to contain all daring inventiveness." But these, she says, "were scorned by Ulysses, / full of longing to see and know." After retelling Dante's version of the hero's end, Fortune adds that "time will come when the vile markings / will become illustrious for the sailor / and the recalled seas, kingdoms, and shores / that you ignore will too be famous."3 Tasso read in Dante's account of the transgression both the marking of limits and a promise of adventurous fulfillment.

The twinning of the curiosity that leads to travel and the curiosity that seeks recondite knowledge is an enduring notion, from the Odyssey to the Grand Tours of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The fourteenth- century scholar known as Ibn Khaldun, in his Al-Muqaddima, or Discourse on the History of the World, noted that travel was an absolute necessity for learning and for the molding of the mind because it allowed the student to meet great teachers and scientific authorities. Ibn Khaldun quoted the Qur'an: "He guides whom He will to the right path," and insisted that the road to knowledge depended not on the technical vocabulary attached to it by scholars but on the inquisitive spirit of the searcher. Learning from various teachers in different places of the world, the student would realize that things are not what any particular language names them. "This will allow him not to confuse science and the vocabulary of science" and help him understand that "a certain terminology is nothing more than a means, a method."4

Ulysses' knowledge is rooted in his language and in his rhetorical ability: the language and the rhetoric bestowed upon him by his creators, from Homer to Dante and Shakespeare, from Joyce to Derek Walcott. Traditionally, it was through this gift of language that Ulysses sinned, first by inducing Achilles, who had been secreted at the court of the king of Scyros to escape the Trojan War, to join the Greek forces, which led to the death from a broken heart of the king's daughter Deidamia, who had fallen in love with him; second, by counseling the Greeks to build the wooden horse by means of which Troy was stormed. Troy, in the Latin imagination inherited by the European Middle Ages, was the effective cradle of Rome, since it was the Trojan Aeneas who, escaping the conquered city, founded what was to become, many centuries later, the core of the Christian world. Ulysses, in Christian thought, is like Adam, guilty of a sin that entails the loss of a "good place" and, consequently, the means of the redemption brought on by the commission of that sin. Without the loss of Eden, Christ's Passion would not have been necessary. Without Ulysses' evil counsel, Troy would not have fallen and Rome would not have been born.

But the sin for which Ulysses and Diomedes are punished is not clearly stated in the Commedia. In the eleventh canto of the Inferno, Virgil takes time to explain to Dante the nature and place of each sin of fraud punished in Hell, but after locating hypocrites, flatterers, necromancers, cheaters, thieves, simonists, panders, and barrators in their proper places, he dismisses the sinners of the eighth and ninth chasms as simply "the same kind of filth." Later on, in the twenty-sixth canto, describing to Dante the faults committed by Ulysses and Diomedes, Virgil lists three: the trick of the Trojan Horse, the abandonment of Deidamia, and the theft of the Palladium. But none of these leads precisely to the nature of the fault punished in this particular chasm. The Dante scholar Leah Schwebel has provided a useful summary of the "slew of prospective crimes for the fallen hero, running the gamut from original sin to pagan hubris" imagined by successive readers of the Commedia, and concludes that none of these plausible interpretations is ultimately satisfactory.5 And yet if we consider Ulysses' sin as one of curiosity, Dante's vision of the wily adventurer may become a little clearer.

As a poet, Dante must construct out of words the character of Ulysses and the account of his adventures, as well as the multilayered context in which the king of Ithaca tells his story, but he must also, at the same time, refuse his ardent storyteller the possibility of reaching the desired good. Travel is not enough, words are not enough: Ulysses must fail because, driven by his all- consuming curiosity, he has confused his vocabulary with his science.

Because Dante the craftsman has to submit to the adamantine structures of the Christian Otherworld as a framework for his poem, Ulysses' place in Hell might be largely defined as that of a soul who is guilty of spiritual theft: he has used his intellectual gifts to deceive others. But what has fueled this trickster impulse? Like Socrates, Ulysses equates virtue and knowledge, thereby creating the rhetorical illusion that knowing a virtue is the same as possessing that virtue.6 But it is not in the exposition of this intellectual sin that Dante's interest lies. Instead, what he wants Ulysses to tell him is what drove him, after all the obstacles Neptune set up on the return voyage from Troy, to sail not home to his bed and hearth but onwards into the unknown.7 Dante wants to know what made Ulysses curious. To explore this question, he tells a story.

Throughout our convoluted histories, stories have had a way of reappearing under different forms and guises; we can never be certain of when a story was told for the first time, only that it will be not the last. Before the first chronicle of travel there must have been an Odyssey of which we now know nothing, and before the first account of war, an Iliad must have been sung by a poet who is for us even fainter than Homer. Since imagination is, as we have noted, the means by which our species survives in the world, and since we were all born, for better or for worse, with Ulysses' "ardore," and since stories are, from the very first campfire evenings on, our way of using imagination to feed this ardore, no story can be truly original or unique. All stories have a quality of dejh lu about them. The art of stories, which seems not to have an end, in fact has no beginning. Because there is no first story, stories grant us a sort of retrospective immortality.