Talmage Powell Murder Gets Easier

The morning was clear and warm with the first whisperings of spring echoing northward. The lettering on the windows still looked nice: JOSEPH THOMAS, New and Used Books, Magazines, Collector’s Items. He still loved the pleasant mustiness, the warm gloom of the store with its hundreds of used books and magazines that crowded the shelves. He was young and in good health. But a lump of midwinter lay inside Joey Thomas.

To begin with, he’d about decided that as a business man he was too small a flicker even to term a flash in the pan. His ravening creditors had promised to claw him to pieces and peddle the parts to medical schools.

Then there was his girl, Cora. She had, he thought, a one track mind. She’d fallen right in with his plans, when he’d come out of the army those months ago, to establish his used-book business, live off of it, and make a writer of himself. He’d done one book — Corpse In The House by Joseph J. Thomas — a psychological thriller about a man who murdered his wife and walled her in a tiny alcove upstairs, using quicklime generously, only to believe that he began hearing scratchings on the floor of the alcove. Three scratches, a pause, three scratches, a pause... Like bony fingers trailing across the protagonist’s ceiling, reminding him that he had killed his wife on the third day of the third month of the year.

The royalties off of Corpse In The House had been eaten by the store; the second book hadn’t found a publisher anywhere; and Joey knew he’d never finish the third before bankruptcy and he became bosom friends.

He was ready to chuck the deal, get a job, marry Cora. That’s all he wanted out of life, really, to marry Cora. But he wasn’t having any of this business of two starving as cheaply as one. And she grimly insisted that he stick to his guns. Thus they had reached an impasse. He wouldn’t marry her until he could support her, and she wouldn’t allow him to chuck the dreams overboard.

But at the moment, Joey’s mind was dragged from those worries. Besides himself, there were three people in the store. Leroy Dorrell was thin, tall, well-tailored to have no visible means of support. A ring on his right hand glittered like genuine diamond; his eyes, pale green, glittered too. A star-shaped scar marred the dark tan on one of Mr. Leroy Dorrell’s cheeks.

Beside Dorrell, faintly plump, a silver fox about her shoulders. Marge Krayer stood, her blood red lips curled at wizened old man Arnheit. Marge Krayer had platinum hair that made Joey wish he’d gone in the peroxide business. He knew Dorrell and Marge Krayer only casually, seeing them now and then in Tony’s bar down the block, where Joey occasionally took a short beer.

Joey turned his back on the pair, trying to shush Mr. Arnheit, who was telling the world loudly, “Dorrell, you’re an illiterate punk!”

Mr. Arnheit roomed in the old brownstone down the block. He was wiry, tough, an inveterate talker, a browser in book stores. One of Joey’s steadiest customers, except that Mr. Arnheit never bought anything.

A few moments ago, Leroy Dorrell and Marge Krayer had strolled in the store. Just looking they’d said. Dorrell had picked up a copy of Poe’s collected works — price twenty cents — from the cluttered table near the front of the store, read a few lines of The Raven aloud and promptly laughed with thin sarcasm. Mr. Arnheit, who’d been sitting in the back of the store, had risen to the attack.

“Poe, you young punk, worked with the fine exactitude of an architect,” Mr. Arnheit now shouted, disregarding Joey’s shushing entirely.

Marge Krayer fingered her platinum hair and told Dorrell, “Why don’t you kick the old fool’s teeth in, darling?”

Mr. Arnheit, who read racing forms as well as Poe, who had no visible means of support himself, saw red. “You think I’m afraid to stand up to you? If more people...”

“Listen,” Joey said, “this is a place of business!” Then he hoard the clamping footsteps upstairs and groaned again. Ralph Ballinger’s sleep had been disturbed. Ballinger was a big, strapping man with flaming hair, deep red freckles so thick on his face he seemed constantly on the verge of apoplexy. He occupied the flat over the store; once before when a gang of noisy kids had been in quest of tattered comic magazines, Ralph Ballinger had let Joey know in no uncertain terms that he worked nights and would countenance no undue noise downstairs. Gossip had it that Ballinger worked very hard indeed, at sucker poker, blackjack, and trained dice. Now Mr. Ballinger ignored the front stairs that led down from his flat to the street Joey heard him pounding down the narrow back stairs.

Leroy Dorrell was moving forward, urged by Marge Krayer, and Arnheit was telling Leroy to stand back, when Ballinger’s steps reached the bottom of the narrow back stairs, came across Joey’s store-room. Ballinger appearing in the doorway that opened to the storage room in back of the store. Ballinger’s red hair was tousled. He wore a faded robe, below which showed pajama legs and house shoes. His foghorn voice joined in the fray. “What the hell is all the shouting about, Thomas? I thought I told you...”

“I was insulted,” Dorrell explained, eyeing Ballinger’s hulk.

“I didn’t insult anybody,” wiry Mr. Arnheit howled, “I just spoke the truth! Edgar Allan Poe...”

Ballinger advanced in the store. His eyes were red-rimmed, his freckles pale. He appeared, conceded Joey, to need sleep badly. “If I don’t get some shut-eye,” Ballinger said, “I’m going to take this place apart with my bare hands.”

The Joseph J. Thomas book business at least deserved to die in peace, Joey decided. He walked behind the counter, picked up the phone. “Nobody’s taking anything apart,” he said. “I’m going to call a riot squad if this place isn’t cleared in exactly twenty-five seconds.”

They tossed a last upheaval of choice language at each other; Ralph Ballinger glared with his red-rimmed eyes. Then Dorrell swooshed out with Marge Krayer on his arm, Ballinger clomped back upstairs to his bed, and Mr. Arnheit slammed the door and turned down the sidewalk.

Joey sighed and began straightening magazines. It was fifteen minutes later when he noticed the new copy of Eman’s Political Economy on the showcase near the front of the store. Joey frowned. He knew the contents of the store like the palm of his hand. He didn’t recall purchasing Mr. Eman’s tome. Someone must have laid it on the counter, forgotten it. But it hadn’t been there when he’d opened up this morning. Joey would have noticed it dusting.

He riffled through the book, a habit of his the whole neighborhood knew. He’d found pressed flowers, four leaf clovers, a prized cake recipe once in a travelogue he’d bought from Mrs. McDougle, who’d thanked him profusely when he’d returned it. Now his hand jerked to a stop, riffled back. There between pages fifty seven and fifty eight it was.

A nice, crinkly thousand dollar bill...

Joey’s hands trembled. A thousand bucks could mean a lot to him. Then he jammed the bill in his wallet, muttered to himself, went out, and locked the door behind him.

In the next half hour Joey endured Ralph Ballinger’s blasphemy, a discourse on economic politics from Mr. Arnheit, and cold, abrupt answers from Leroy Dorrell and Marge Krayer, whom he found in Tony’s bar.

None of them had left the book in his store. He’d mentioned only the title to them of course. If those four had known what the book contained, Joey knew he’d have likely been accused of stealing three other copies.

Yet they’d been the only people in the store that morning — unless someone had come in and out while he’d been in back, early, in the stock-room. On the sidewalk before Tony’s bar, be reached a decision. He’d take the bill to the bank, deposit it in his account. If no one called in thirty days, he could legally figure finders keepers. He turned and headed for the bank — and from there it was only a short trip to police headquarters.

They were very nice at headquarters. About six cops grouped around him in the small room. One of them offered a cigarette. Joey needed it.

The big, bald cop with the sagging face and frigid blue eves introduced himself as Harry Crenshaw. He was saying, “So you took the bill to the bank. The teller knew you weren’t in the habit of depositing thousand dollar bills. He asks you to wait a moment, checks the bill.”

Joey felt needles of sweat on his forehead. “I thought the bill was counterfeit when the teller and bank guard closed in on me. I tried to explain, but they had the beat cop on hand too. Then presto, here I am.”

They didn’t smile. Crenshaw said, “The bill was worse than counterfeit. You recall the armored truck robbery several months ago where the crooks used home-made tear gas guns to knock out the guards?”

“I read about it,” Joey admitted.

“A half million was taken,” Harry Crenshaw said. “This grand note you tried to deposit, Thomas, was part of the loot.”

Joey’s voice was like dry sticks breaking. “I’ve told you the truth! I found that bill in a copy of Eman’s Political Economy!”

Crenshaw smiled at last. “We haven’t doubted your word for a moment, Mr. Thomas. You may go now.”

“Go?” Joey said blankly, rising hesitantly.

“Certainly, and won’t you have another cigarette?” Crenshaw said.

In a daze, Joey left headquarters. But the daze had worn off by the time he reached the store. He was in a jam, he knew, a real jam. They’d let him go because they were positive he’d lead them, sooner or later, to the rest of the loot. If he didn’t, they’d figure he was protecting his cronies in the robbery. Patience gone, they’d run him in.

No one had seen him find that bill. He had nothing to back his crazy story. They’d play a cautious game, keep him shadowed. It would end when they’d wound a twenty year sentence around his neck...

Joey braked his ramshackle coupe before the snug brick house with the small lawn where Cora Lail lived, keeping house for her father and two brothers until she had a home of her own.

She answered Joey’s knock, a small, lively faced girl with brown eyes and silky auburn hair that glinted in the sunshine.

“Joey! This is nice!” She took his hand, drew him inside. Joey looked at her a moment; then the memory of Crenshaw’s sardonically smiling face jerked him back from the clouds.

“Are you going to be very busy today, hon?”

“Not terribly...” She was looking at him closely. “What is it, Joey?”

“Nothing... That is, I wondered if you’d watch the store for me awhile this afternoon, when you’re all through here. I can leave the key at the bake shop across the street.”

“Of course, Joey, but...”

“I just want to check the sale of a book,” he said. “Eman’s Political Economy. The book was left in the store. The only four people who could have left it deny doing so. You see, I... Well, it’s important that I find out, if I can, the store that made the sale, to whom they sold the book.”

“But, Joey, I... if something’s wrong, you should tell me. It would be almost impossible to find the purchaser of a book. It’ll take you hours to check every new and used book store in town.”

“I know...” His lips felt dry. “But it’s the only angle I can think of. Whoever left that book wouldn’t admit...”

She caught his arm. “Joey, you...”

“I’ll tell you later, hon,” he broke in. If he got a lead on that book, he was thinking, no need to worry her needlessly. He was sorry he’d let anything show on his face. He forced a smile. “It’s nothing, really. I just didn’t want to leave the store closed all day. We might sell a few used magazines.”

He pecked her forehead with his lips. “And don’t let your imagination run away with you! I’ll see you later.” He left the house quickly, got in his car. Watching the rear view mirror, he saw the black, inconspicuous sedan pull away from the curb two blocks behind him. Crenshaw. Until he’d cracked this thing, Joey knew he wouldn’t be clear of the police. A drop of sweat crept under his collar.

It was twilight, stores closing, sidewalks swarming with people hurrying home, when he finished his task. He was limp with fatigue, from searching records, more or less opened to him since he was a fellow book dealer, and from questioning salespeople in the book stores. He had also chased down a few hopeless leads, one sale of Eman’s economic work to a college professor, another to an eccentric millionaire. He’d presented himself as a buyer of exclusive Americana well enough to wriggle in both men’s libraries long enough to ascertain that their copies of Political Economy were still in their shelves.

All the while he knew that Crenshaw was back there somewhere in the traffic, in the crowds. He never caught sight of the bald, homely faced detective, and that made it worse. Like playing tag with a ghost. Joey looked hollow-eyed when he ran his car in the mouth of the alley a couple of doors up from the store.

He entered his book store, said, “Hi, hon.” No one answered. He waited a moment in the renter of the gloomy store, thinking that Cora was in back. He called her name again. The thick silence swallowed the words.

He started toward the back of the store. At the rear counter he drew up, sharply. A stack of magazines had been knocked to the floor behind the counter, trampled, twisted, their pages torn. The counter sat at a faintly crooked angle, as if a struggling body had slammed against it.

Joey felt his heart hammering. A gleam caught his eye. He bent over the mussed magazines, picked up a brooch with the monogram: C. L. Cora’s brooch. Bent, twisted, a hit of the cloth from her dress still caught in the pin.

Joey breathed deep and hard, but it didn’t steady him. Flesh knotted coldly along his spine as he called her name again, headed for the store-room in back.

The store-room was dark, silent. He fumbled, found the hanging overhead light. He clicked the switch. A wan, yellow glow spilled over empty cartons, stacks of magazines and books unfit for sale, waiting for the junk man. Then Joey saw the woman lying in the far corner. Not Cora, a blond woman. Marge Krayer. But she wasn’t plump looking any longer. She was limp, and bloody, and dead.

Joey had seen death before, but not in this setting. He closed his eyes, shuddered, and involuntarily backed away. His jaw muscles worked, and he opened his eyes again, looking at the bloody knife beside Marge Krayer. He knew what had happened. Marge had entered through the alley door. Someone had been close behind her, murdered her. Cora, in front, had heard the commotion. The killer had struck her, dragged her away to assure her silence.

Joey wondered if Ralph Ballinger upstairs had heard anything. But Ballinger always left his flat at five — Joey could set his watch by it — to go downtown for supper and a few drinks before his nightly poker. Or Arnheit, perhaps. He stayed around the store a lot. If he had been around and seen or heard anything, Cora might be safe in the hands of the police by now. But Joey had a hunch he’d insulted Arnheit, along with Marge Krayer, Dorrell, and Ballinger, this morning. And if the old man had seen and reported anything, the police would be here now.

Joey knew he was clutching at wisps of fog. The killer was still free, leaving a corpse planted here in Joey’s store, and taking Cora with him.

Joey moved a step toward Marge Krayer’s contorted face. How about Crenshaw, the cop? He’d be hovering around in the neighborhood, keeping an eye on the store. If he should decide to amble in and have another talk with Joey, finding Joey here with what was left of Marge Krayer...

It was as far as Joey’s thoughts went. He heard the squeak of the door behind him. The thought flashed through his mind that someone had been in the storeroom when he’d entered out front. Whoever it was had heard Joey coming toward the back, had sprung behind the door, using it for concealment when Joey’d swung it open.

Joey was half-turned when the blow caught him in the temple. His head was filled with brilliant lights. Then they all went out.

As Joey’s head cleared, he was first aware that night had fallen completely, deep and black. He heard the humming of a motor, felt the jogging motion that jolted him now and then; occasionally he saw the reflections of lights flashing past. He was on the floor mat of the rear of a sedan. As full consciousness returned, the ache in his head was joined by a multitude of aches and agonized tinglings in other parts of his body. He tried to move and couldn’t. Cramped, he was tied like a trick escape artist. Only he was no Houdini.

He craned his neck, saw the shadow of the man driving. His voice wheezed, “Arnheit? Ballinger? Dorrell?”

The man in front laughed. “Make up your mind, punk.” It was Dorrell. It had had to be one of the three. Only four people could have left that book in his store, and one of them — Marge Krayer — was dead.

His voice had needles in it. “Where’s Cora?”

“Your dame? She’ll follow along shortly, chum, when we get through with you,” Dorrell told him.

Joey sagged back, wishing the cold fingers would quit squeezing his stomach dry. “How’d you get we out? The cop shadow...”

“Simple.” Dorrell glanced over the top of the seat, his face very dark in the weak dash light. “We knew the cops would have a tail on you as soon as you tried to cash that bill. I ran my car in the open end of the alley, loaded you, and drove out. The cop watching your store gave me a long look, but he couldn’t see you, chum. You were below window level.”

Joey pictured it in his mind. The alley was made in a square U form, cutting between buildings north of Joey’s store, passing behind most of the block, then cutting back to the street south of the book shop. Joey remembered that he had parked his car at one end of the alley. Dorrell had brought him out the other end. The cop shadow, seeing the store, both ends of the alley, noting that Joey hadn’t emerged from the store and that his car was still parked, quite likely was still bruising his feet in the shadows across the street, naturally believing Joey to be still in the store.

Joey tried to shift himself; a muscle in his thigh cramped until he set his teeth against the knotted pain.

“And what are you going to do with me, Dorrell?”

“Arrange a disappearance,” Dorrell said easily. “The cop’s going to get tired cooling his heels sometime tonight. He’ll take a look in your store. He’ll find Marge Krayer — and enough hot money in her bag to convince them that she was mixed in that armored truck robbery. Your dame, they’ll say. You got in a squabble over the dough after you tried to cash a grand note and found the dough was still hot. You killed her, they’ll say. They’ll hunt you. From now on. But they’ll never think of looking for you at the bottom of the river with a boulder tied about your middle. It’ll serve two purposes — throw the blame for the robbery and for Marge’s death in the wrong direction, leaving me and the boss in the clear, able to spend that half million bucks one of these days when it finally cools, and it’ll get you out of the way. You’re a nosy, smart guy, Thomas. You might have eventually found where that copy of Political Economy came from.”

Joey licked his lips. Dorrell was talking sense, all right. Macabre, unholy sense. Joey said, “But what really happened goes something like this. The whole neighborhood knows my habits, along with the fact that I’m just about bankrupt. You were fairly certain I’d find the thousand dollar bill. So it was planted on me. You had to know if the money was still hot. If I cashed the bill okay, you could start spending. It would be worth a paltry thousand out of a half million to know that. But if I got canned cashing the bill, you’d have warning to hold the dough awhile longer. Nobody would suspect anyone but me. That was worth a thousand too.

“But you’d been holding the dough for a long time already. Marge Krayer’s nerves were breaking. When she found that the money was useless, it drove her frantic. She was mixed in a hellish mess with nothing to show but a pile of hot money. She wanted out of the whole thing. So she was coming to me. She wanted a go-between in making a deal with the district attorney. She was afraid to go directly to the D.A. She knew I’d be open to any suggestion that would get my neck out of it and that I’d fix things, getting plenty of assurance for her safety if she turned state’s witness, before I revealed her identity to the district attorney.

“You tumbled to Marge’s intentions. You followed her through the rear entrance of the store, stabbed her to death. Cora heard the commotion, appeared in back. You caught her at the rear counter of the store. If you’ve harmed her...”

“You’re not in a position to make threats.” Dorrell glanced over the seat again. The small scar on his cheek caught light, like a pale star. “You got one little thing wrong, though. I didn’t kill Marge. In a way, I liked her, had drinks in Tony’s bar with her.”

“Then who did kill her?” Joey asked. “Who is the head man in this mess?”

“You’d like to know,” Dorrell jeered. He pulled the car over to the aide of the road, slowing, and turned sharply. Joey had noticed that passing headlights had been getting scarcer. Now they stopped altogether, and from the lurching of the car, Joey knew Dorrell had turned off on a lonely country road. He dragged the cool night air in his lungs. It tasted nice, the way anything precious tastes when there is only a few more minutes to have it.

Dorrell stopped the car, got out and opened the rear door. He was a tall, thin shadow standing over Joey as he dragged Joey out and dumped him on the dusty earth of the road. The breeze whispered through the pines; a night creature scurried through the dense undergrowth. The night was lonely, shrouded in silence.

Dorrell laid a flashlight on the fender of the car. He knelt, planting his knee in the small of Joey’s back until the gravel of the road bit in Joey’s chest. He could feel Dorrell cutting him loose.

Then Dorrell sprang back. “I’d just as soon let you have it now as later, Thomas. So watch the way you move.”

Joey lay a moment, retching, as circulation returned to his arms and legs. Dorrell said harshly, “Get on your feet, Thomas.”

Joey clambered upright. His feet felt like huge, swollen things, and every step he took was a floating giant-stride.

Very faintly, he could bear the murmur of the river in the distance. Beside the road, the hill dropped away steeply, leading down through the pit of the night to the river. He flashlight and gun prodding him, Joey stepped off the edge of the road.

They moved without speaking, Dorrell silently nerving himself for the bloody task ahead. The rustle of undergrowth, the cracking of twigs marked their slow, sliding progress downward.

They were halfway to the river and through breaks in the foliage Joey could see the gleaming silver of the water now and then. Dorrell a scant two yards behind him, they passed under the yawning branches of a mature maple tree.

Joey slipped, flailed his arms, grabbed a wrist-sized limb of the maple, his feet flying from beneath him. Dorrell shouted, squeezed the trigger nervously, missing Joey’s diving form.

Joey dung to the branch, until it had bent as far as his weight would instantly take it. Then he let go. He beard Dorrell shout again, a startled sound filled with pain this time, as the branch swished back to smash Dorrell in the face and drive him to his knees.

It gave Joey a moment. Gravity and his feet sent him hurtling down the hillside, into the undergrowth. But Dorrell still had the light and the gun and Joey thought: “He knows he’s got to get me. If I get away it’s his neck as an accessory to murder. He’s desperate. He’s got to get me...”

Joey rolled behind the rough bole of an oak. His fingers found a smooth sandstone, half the size of a brick. A stone against a flashlight and gun. He lay a moment, listening.

Dorrell was charging crazily down the hill. Berserk, he shouted, “Come back, you fool! You’ll never get away. I got the gun. I can see where...” He fired twice, and Joey knew Dorrell was shooting at shadows, any kind of shadow, wallowing through the undergrowth.

Joey raised himself to his knees, his feet, the stone clutched in his fingers.

Dorrell fired at the crashing stone. Then his light swung, blinding Joey as he bunched himself and sprang for the undergrowth below the oak.

Mouthing laughter, Dorrell came after him, holding his fire now, his light catching Joey only fleetingly through the brush, waiting until he had Joey out of the timber, limned against the river.

Then Joey heard the gun fire once more, scant yards behind him. It sounded muffled, and the sounds of Dorrell’s reckless charge ceased.

Joey paused, the silence beating against his ear drums, sudden, deep. The flashlight had gone out. Joey turned cautiously, staring at the brush, his gaze moving until it reached the moonlit spot where it stopped. Joey saw the gnarled root that had tripped Dorrell in his headlong plunge, the way Dorrell’s hand had twisted, burying the muzzle of the gun in his throat. Dorrell’s blood gleamed like crimson satin in the moonlight. Joey knew he was dead.

He stood a moment, chilled by death. Then he dug his toes in and started back up the long, silent hill-side. If there was a lead to Cora, he felt, it had to be on the scene of the crime; where she’d been snatched. In his store.

Joey pulled Dorrell’s car in the alley, up near the rear entrance of the store. He sat a moment, wondering if the police stake-out had become impatient. But he saw no signs of the place being filled with police buzzing about the rediscovered body of Marge Krayer. He got out of the car, entered the store-room.

Marge Krayer hadn’t been moved. Everything was the same. The lights still burned out front, turned on, he knew, by Cora at the first approaches of dusk. If his time element fitted, it had been just about the last thing she’d done.

He walked through the store-room, down the shop between the high racks of books. At the front door he scanned the, street. Across the street, three doors down, he could see the dim shadow. It wouldn’t be Crenshaw now; some other cop would be on duty, but it was a cop just the same, watching Joey’s car at the southern mouth of the alley and the lighted store like a man of stone. Book work, Joey thought. He thinks I’ve been in back the past hour and a quarter, doing book work.

Joey stretched, spreading his arms out wide in an elaborate gesture, the movements of a man who might have been over a desk for more than an hour; he knew he was plainly silhouetted against the glass door to the cop.

He turned and strolled back down the length of the store. He bent over the mussed, twisted magazines where Cora had struggled, his hands shaking. Nothing. Nothing but magazines. He pushed the counter out further, knowing the cop couldn’t see this deep into the store, from across the street and three doors down. The movement was jerky. A tottering stack of books fell down from the other end of the counter to the floor. With a crash.

Joey wiped his coat sleeve across his face. He bent once more, began spreading the magazines.

Then he heard the scratchings, counted them, listened to the pause, heard the scratchings on the ceiling renew. It felt as if every hair were marching across his scalp. A scene in his book, Corpse In The House, a scene he had himself created in his mind, was coming to life. The woman walled in the alcove, the man downstairs, hearing the scratchings on the ceiling, reminding him he had murdered her on the third day of the third month. Only this time it was not a murderer listening. Joey stood with his hands clenched, his head tilted back, his mouth slightly open, counting the faltering sounds. Three scratches... a pause... three scratches...

He went back in the storage room, opened the rear stairway door that led up to Ralph Ballinger’s flat. The stairs were narrow and dark before him. He started up, silent, and it seemed as if the darkness were alive about him.

The doorway at the top opened into Ballinger’s kitchen, though Joey knew the red-headed, densely freckled man did no cooking and hired none done.

Joey moved across the kitchen, furniture looming in the glow from the corner street light that filtered in. He heard nothing but those faint scratching sounds, guiding him. He reached a closet door, flung it open. He heard her breathing, saw her huddled form below Ballinger’s hanging suite. He dropped to his knees, tore the gag and bonds away. When he’d helped her to her feet, she clung to him, small, warm, sobbing.

“Joey! I... I was... afraid... you wouldn’t understand the sounds or hear me. I could hear you walking around down there and the only way I could think of getting you up here...”

“...Came out of the book,” Joey supplied softly. “Sure, hon. You did most of the typing, listened to me read passages back every time I reworked one. I knew...”

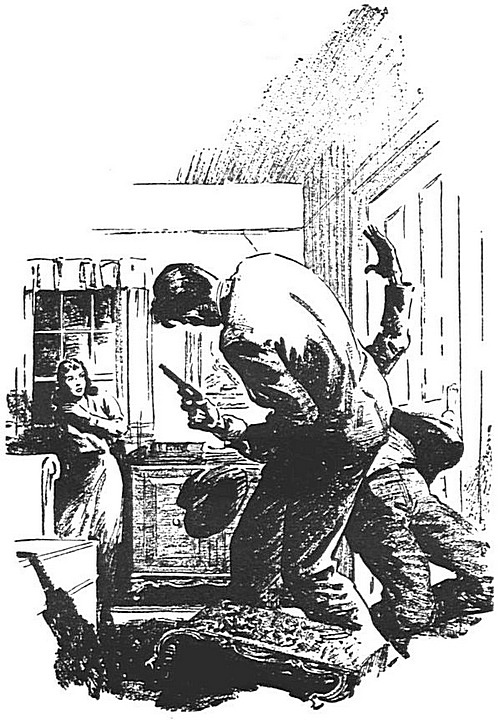

He and Cora whirled as a switch clicked, splashing light over the room. A man stood in the corner, one hand still on the light switch, the other hand holding a gun. There was murder in the set of his mouth, the light in his eyes.

It was Arnheit.

But Arnheit did not look like a book-lover, a man who went to bat for the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Not now. He looked wizened and incredibly old and evil. “I was watching from the back window when Dorrell’s car came in the alley,” Arnheit said. “I thought it was Dorrell returning from his task with you; then you got out and I saw it wasn’t. I let her think I’d gone, hoping she’d manage to get you up here, Joey.”

“Dorrell made a mistake or two,” Joey said.

“So I see,” Arnheit nodded. “But it will turn out just as well, if not better. A half million to spend by myself, browsing in book stores all over the country,” he smiled mirthlessly.

“No,” Cora breathed, “they’ll get you. You knew that Ballinger left his flat every day at five sharp. You thought you’d be safe in bringing me up here until you could decide what to do with me, after you murdered Marge Krayer. You knew that Ballinger had gone, that the flat would be vacant until tomorrow morning. You had little choice anyway but to bring me up the back stairs and hide me here. You were almost cornered. You couldn’t lug an unconscious girl all over town.”

“I should have killed you,” Arnheit told her. “and Joey as well and given your bodies to Dorrell. Perhaps he could have at least succeeded in getting rid of you then.” His gaze dropped back to Joey, a twisted smile on his old, wrinkled mouth. “When you write your next book, Joey, don’t work on the assumption that murder gets easier. It never does. I was a fool. I hesitated because murder and murder added to it was becoming so devilishly hard. You know why I killed Marge?”

Joey nodded. “I think I know everything now. You had Dorrell and Marge come in the store this morning to create a scene and give you a chance to plant the book with the thousand dollar bill in it. Several people in the store also made me uncertain where the book had come from. You’ve held that half million until it was searing the skin off your fingers. You had to know if you could spend it in safety. When the police go out and pick up Dorrell’s body and break you down and find that loot you’ve got hidden away, they’ll tie up the angles. Arnheit, all of them. It took a brain like yours to cook up that armored truck robbery in the first place. Arnheit.”

“But the police, Joey, aren’t getting me! Didn’t you know? Didn’t you...”

He broke off as soft footsteps sounded outside the door, coming up the front stairs. His gaze flicked involuntarily to the door. Joey was almost on top of him before Arnheit could jerk his glance back and fire.

Joey heard the bullet shower planter. His hands closed on Arnheit’s forearm. Something a tough buck sergeant had once taught him came back to Joey. He jerked his arm, bent his body. He heard the snapping of Arnheit’s bone. The old man screamed, and Joey set his teeth and hit him on the point of the chin. Arnheit would suffer enough, Joey decided grimly. Might as well give him the temporary anesthesia of unconsciousness with that broken arm.

Cora moved softly up in the crook of his arm. They looked at the small man and Cora breathed. “Somehow he reminds me of a tiny coral snake, curled in the sun. small to be so deadly...”

The door slammed back, interrupting her. Ralph Ballinger stood in the doorway, freckles flaming. Behind him, craning their gazes over his shoulder were four men who exuded the odor of solid citizen.

“What the hell is going on here?” Ballinger demanded.

“Just wait’ll you find out,” Joey said, “I... we... that is, your poker games.”

Ballinger glared down at Arnheit, at Joey and Cora, at the room in general. “Poker games? You nitwit, doesn’t it stand to reason that, playing every night, seven nights a week, the cops would be wise and hound us to damnation and gone, forcing us to move the game constantly? Since the whole neighborhood was so positive I was never home after dark, we’ve been coming slipping back here the past five nights. Thomas, you’d better start explaining what...”

“Well,” Joey said, “in the first place, there’s a corpse downstairs.”

Ballinger and four solid citizens shouted, “Corpse? Did you say...”

They were interrupted by the arrival of the cop from across the street who’d been shadowing Joey, to the best of his knowledge. The cop had heard Arnheit’s gunfire. Now he took over, and Joey was glad enough to go over all the details with the squad that came from headquarters shortly.

Later over coffee, Cora squeezed his hand and said, “After the publicity you’re going to get, Joey, you’ll have to fight off the publishers with a big stick. Your books...”

He glanced about the smug, quiet lunchroom, the counterman grinning over a comic book. “We won’t even use a small stick,” he confided.

Cora smiled at him. “Mr. Ballinger was very indignant, says he’s just a quiet, nice gentleman who likes a game. In fact, losing his sleep, the place cluttered with corpses, Mr. Ballinger is vacating the flat.”

She paused, looking at Joey. He studied his coffee cup a moment, looked up at the counterman. “Say, Mac, you know where to find a justice of the peace this time of night?”

The counterman laid aside his magazine. He walked around the counter, pulled up a chair, and leaned his elbows on Joey’s and Cora’s table. “You asked the question of the right man, brother,” he assured Joey gravely. “This justice I know is a regular sort of guy. He is positively the finest marrying Sam...”

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ