THE

HERETIC

QUEEN

To my mother, Carol Moran

Without you, this would never have been possible.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

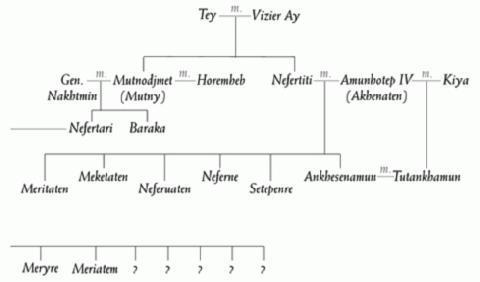

THERE WAS A time in the Eighteenth Dynasty when Nefertiti’s family reigned supreme over Egypt. She and her husband, Akhenaten, removed Egypt’s gods and raised the mysterious sun deity Aten in their place. Even after Nefertiti died and her policies were deemed heretical, it was still her daughter Ankhesenamun and her stepson, Tutankhamun, who reigned. When Tutankhamun died of an infection at around nineteen years of age, Nefertiti’s father, Ay, took the throne. With his death only a few years later, the last link to the royal family was Nefertiti’s younger sister, Mutnodjmet.

THERE WAS A time in the Eighteenth Dynasty when Nefertiti’s family reigned supreme over Egypt. She and her husband, Akhenaten, removed Egypt’s gods and raised the mysterious sun deity Aten in their place. Even after Nefertiti died and her policies were deemed heretical, it was still her daughter Ankhesenamun and her stepson, Tutankhamun, who reigned. When Tutankhamun died of an infection at around nineteen years of age, Nefertiti’s father, Ay, took the throne. With his death only a few years later, the last link to the royal family was Nefertiti’s younger sister, Mutnodjmet.

Knowing that Mutnodjmet would never take the crown for herself, the general Horemheb took her as his wife by force, in order to legitimize his own claim to Egypt’s throne. It was the end of an era when Mutnodjmet died in childbirth, and the Nineteenth Dynasty began when Horemheb passed the throne to his general, Ramesses I. But Ramesses was an old man at the start of his rule, and when he died, the crown passed to his son, Pharaoh Seti.

Now, the year is 1283 BC. Nefertiti’s family has passed on, and all that remains of her line is Mutnodjmet’s daughter, Nefertari, an orphan in the court of Seti I.

THE

HERETIC

QUEEN

PROLOGUE

I AM SURE that if I sat in a quiet place, away from the palace and the bustle of the court, I could remember scenes from my childhood much earlier than six years old. As it is, I have vague impressions of low tables with lion’s-paw feet crouched on polished tiles. I can still smell the scents of cedar and acacia from the open chests where my nurse stored my favorite playthings. And I am sure that if I sat in the sycamore groves for a day with nothing but the wind to disturb me, I could put an image to the sound of sistrums being shaken in a courtyard where frankincense was being burned. But all of those are hazy impressions, as difficult to see through as heavy linen, and my first real memory is of Ramesses weeping in the dark Temple of Amun.

I AM SURE that if I sat in a quiet place, away from the palace and the bustle of the court, I could remember scenes from my childhood much earlier than six years old. As it is, I have vague impressions of low tables with lion’s-paw feet crouched on polished tiles. I can still smell the scents of cedar and acacia from the open chests where my nurse stored my favorite playthings. And I am sure that if I sat in the sycamore groves for a day with nothing but the wind to disturb me, I could put an image to the sound of sistrums being shaken in a courtyard where frankincense was being burned. But all of those are hazy impressions, as difficult to see through as heavy linen, and my first real memory is of Ramesses weeping in the dark Temple of Amun.

I must have begged to go with him that night, or perhaps my nurse had been too busy at Princess Pili’s bedside to realize that I was gone. But I can recall our passage through the silent halls of Amun’s temple, and how Ramesses’s face looked like a painting I had seen of women begging the goddess Isis for favor. I was six years old and always talking, but I knew enough to be quiet that night. I peered up at the painted images of the gods as they passed through the glow of our flickering torchlight, and when we reached the inner sanctum, Ramesses spoke his first words to me.

“Stay here.”

I obeyed his command and drew deeper into the shadows as he approached the towering statue of Amun. The god was illuminated by a circle of lamplight, and Ramesses knelt before the creator of life. My heart was beating so loudly in my ears that I couldn’t hear what he was whispering, but his final words rang out. “Help her, Amun. She’s only six. Please don’t let Anubis take her away. Not yet!”

There was movement from the opposite door of the sanctum, and the whisper of sandaled feet warned Ramesses that he wasn’t alone. He stood, wiping tears from his eyes, and I held my breath as a man emerged like a leopard from the darkness. The spotted pelt of a priest draped from his shoulders, and his left eye was as red as a pool of blood.

“Where is the king?” the High Priest demanded.

Ramesses, summoning all the courage of his nine years, stepped into the circle of lamplight and spoke. “In the palace, Your Holiness. My father won’t leave my sister’s side.”

“Then where is your mother?”

“She . . . she’s with her as well. The physicians say my sister is going to die!”

“So your father sent children to intervene with the gods?”

I understood for the first time why we had come. “But I’ve promised Amun whatever he wants,” Ramesses cried. “Whatever shall be mine in my future.”

“And your father never thought to call on me?”

“He has! He’s asked that you come to the palace.” His voice broke. “But do you think that Amun will heal her?”

The High Priest moved across the tiles. “Who can say?”

“But I came on my knees and offered him anything. I did as I was told.”

“You may have,” the High Priest snapped, “but Pharaoh himself has not visited my temple.”

Ramesses took my hand, and we followed the hem of the High Priest’s robes into the courtyard. A trumpet shattered the stillness of the night, and when priests appeared in long white cloaks, I thought of the mummified god Osiris. In the darkness, it was impossible to make out their features, but when enough had assembled, the High Priest shouted, “To the palace of Malkata!”

With torchlights before us we swept into the darkness. Our chariots raced through the chill Mechyr night to the River Nile. And when we’d crossed the waters to the steps of the palace, guards ushered our retinue into the hall.

“Where is the royal family?” the High Priest demanded.

“Inside the princess’s bedchamber, Your Holiness.”

The High Priest made for the stairs. “Is she alive?”

When no guard answered, Ramesses broke into a run, and I hurried after him, afraid of being left in the dark halls of the palace.

“Pili!” he cried. “Pili, no! Wait!” He took the stairs two at a time and at the entrance to Pili’s chamber two armed guards parted for him. Ramesses swung open the heavy wooden doors and stopped. I peered into the dimness. The air was thick with incense, and the queen was bent in mourning. Pharaoh stood by himself in the shadows, away from the single oil lamp that lit the room.

“Pili,” Ramesses whispered.

“Pili!” he cried. He didn’t care that it was unbecoming of a prince to weep. He ran to the bed and grasped his sister’s hand. Her eyes were shut, and her small chest no longer shook with the cold. From beside her on the bed, the Queen of Egypt let out a violent sob.

“Ramesses, you must instruct them to ring the bells.”

Ramesses looked to his father, as if the Pharaoh of Egypt might reverse death itself.

Pharaoh Seti nodded. “Go.”

“But I tried!” Ramesses cried. “I begged Amun.”

Seti moved across the room and placed his arm around Ramesses’s shoulders. “I know. And now you must tell them to ring the bells. Anubis has taken her.”

But I could see that Ramesses couldn’t bear to leave Pili alone. She had been fearful of the dark, like I was, and she would be afraid of so much weeping. He hesitated, but his father’s voice was firm.

“Go.”

Ramesses looked down at me, and it was understood that I would accompany him.

In the courtyard, an old priestess sat beneath the twisted limbs of an acacia, holding a bronze bell in her withered hands. “Anubis will come for us all one day,” she said, her breath fogging the cold night.

“Not at six years old!” Ramesses shouted. “Not when I begged for her life from Amun.”

The old priestess laughed harshly. “The gods do not listen to children! What great things have you accomplished that Amun should hear you speak? What wars have you won? What monuments have you erected?”

I hid behind Ramesses’s cloak, and neither of us moved.

“Where will Amun have heard your name,” she demanded, “to recognize it among so many thousands begging for aid?”

“Nowhere,” I heard Ramesses whisper, and the old priestess nodded firmly.

“If the gods cannot recognize your names,” she warned, “they will never hear your prayers.”

CHAPTER ONE

PHARAOH OF UPPER EGYPT

Thebes, 1283 BC

“STAY STILL,” Paser admonished firmly. Although Paser was my tutor and couldn’t tell a princess what to do, there would be extra lines to copy if I didn’t obey. I stopped shifting in my beaded dress and stood obediently with the other children of Pharaoh Seti’s harem. But at thirteen years old, I was always impatient. Besides, all I could see was the gilded belt of the woman in front of me. Heavy sweat stained her white linen, trickling down her neck from beneath her wig. As soon as Ramesses passed in the royal procession, the court would be able to escape the heat and follow him into the cool shade of the temple. But the procession was moving terribly slow. I looked up at Paser, who was searching for an open path to the front of the crowd.

“STAY STILL,” Paser admonished firmly. Although Paser was my tutor and couldn’t tell a princess what to do, there would be extra lines to copy if I didn’t obey. I stopped shifting in my beaded dress and stood obediently with the other children of Pharaoh Seti’s harem. But at thirteen years old, I was always impatient. Besides, all I could see was the gilded belt of the woman in front of me. Heavy sweat stained her white linen, trickling down her neck from beneath her wig. As soon as Ramesses passed in the royal procession, the court would be able to escape the heat and follow him into the cool shade of the temple. But the procession was moving terribly slow. I looked up at Paser, who was searching for an open path to the front of the crowd.

“Will Ramesses stop studying with us now that he’s becoming coregent?” I asked.

“Yes,” Paser said distractedly. He took my arm and pushed our way through the sea of bodies. “Make way for the princess Nefertari! Make way!” Women with children stepped aside until we were standing at the very edge of the roadway. All along the Avenue of Sphinxes, tall pots of incense smoked and burned, filling the air with the sacred scent of kyphi that would make this, above all days, an auspicious one. The brassy sound of trumpets filled the avenue, and Paser pushed me forward. “The prince is coming!”

“I see the prince every day,” I said sullenly. Ramesses was the only son of Pharaoh Seti, and now that he had turned seventeen, he would be leaving his childhood behind. There would be no more studying with him in the edduba, or hunting together in the afternoons. His coronation held no interest for me then, but when he came into view, even I caught my breath. From the wide lapis collar around his neck to the golden cuffs around his ankles and wrists, he was covered in jewels. His red hair shone like copper in the sun, and a heavy sword hung at his waist. Thousands of Egyptians surged forward to see, and as Ramesses strode past in the procession, I reached forward to tug at his hair. Although Paser inhaled sharply, Pharaoh Seti laughed, and the entire procession came to a halt.

“Little Nefertari.” Pharaoh patted my head.

“Little?” I puffed out my chest. “I’m not little.” I was thirteen, and in a month I’d be fourteen.

Pharaoh Seti chuckled at my obstinacy. “Little only in stature then,” he promised. “And where is that determined nurse of yours?”

“Merit? In the palace, preparing for the feast.”

“Well, tell Merit I want to see her in the Great Hall tonight. We must teach her to smile as beautifully as you do.” He pinched my cheeks, and the procession continued into the cool recesses of the temple.

“Stay close to me,” Paser ordered.

“Why? You’ve never minded where I’ve gone before.”

We were swept into the temple with the rest of the court, and at last, the heavy heat of the day was shut out. In the dimly lit corridors a priest dressed in the long white robes of Amun guided us swiftly to the inner sanctum. I pressed my palm against the cool slabs of stone where images of the gods had been carved and painted. Their faces were frozen in expressions of joy, as if they were happy to see that we’d come.

“Be careful of the paintings,” Paser warned sharply.

“Where are we going?”

“To the inner sanctum.”

The passage widened into a vaulted chamber, and a murmur of surprise passed through the crowd. Granite columns soared up into the gloom, and the blue tiled roof had been inlaid with silver to imitate the night’s glittering sky. On a painted dais, a group of Amun priests were waiting, and I thought with sadness that once Ramesses was coregent, he would never be a carefree prince in the marshes again. But there were still the other children from the edduba, and I searched the crowded room for a friend.

“Asha!” I beckoned, and when he saw me with our tutor, he threaded his way over. As usual, his black hair was bound tightly in a braid; whenever we hunted it trailed behind him like a whip. Although his arrow was often the one that brought down the bull, he was never the first to approach the kill, prompting Pharaoh to call him Asha the Cautious. But as Asha was cautious, Ramesses was impulsive. In the hunt, he was always charging ahead, even on the most dangerous roads, and his own father called him Ramesses the Rash. Of course, this was a private joke between them, and no one but Pharaoh Seti ever called him that. I smiled a greeting at Asha, but the look Paser gave him was not so welcoming.

“Why aren’t you standing with the prince on the dais?”

“But the ceremony won’t begin until the call of the trumpets,” Asha explained. When Paser sighed, Asha turned to me. “What’s the matter? Aren’t you excited?”

“How can I be excited,” I demanded, “when Ramesses will spend all his time in the Audience Chamber, and in less than a year you’ll be leaving for the army?”

Asha shifted uncomfortably in his leather pectoral. “Actually, if I’m to be a general,” he explained, “my training must begin this month.” The trumpets blared, and when I opened my mouth to protest, he turned. “It’s time!” Then his long braid disappeared into the crowd. A great hush fell over the temple, and I looked up at Paser, who avoided my gaze.

“What is she doing here?” someone hissed, and I knew without turning that the woman was speaking about me. “She’ll bring nothing but bad luck on this day.”

Paser looked down at me, and as the priests began their hymns to Amun, I pretended not to have heard the woman’s whispers. Instead, I watched as the High Priest Rahotep emerged from the shadows. A leopard’s pelt hung from his shoulders, and as he slowly ascended the dais, the children next to me averted their gaze. His face appeared frozen, like a mask that never stops grinning, and his left eye was still red as a carnelian stone. Heavy clouds of incense filled the inner sanctum, but Rahotep appeared immune to the smoke. He lifted the hedjet crown in his hands, and without blinking, placed it on top of Ramesses’s golden brow. “May the great god Amun embrace Ramesses the Second, for now he is Pharaoh of Upper Egypt.”

While the court erupted into wild cheers, I felt my heart sink. I fanned away the acrid scent of perfume from under women’s arms, and children with ivory clappers beat them together in a noise that filled the entire chamber. Seti, who was now only ruler of Lower Egypt, smiled widely. Then hundreds of courtiers began to move, crushing me between their belted waists.

“Come. We’re leaving for the palace!” Paser shouted.

I glanced behind me. “What about Asha?”

“He will have to find you later.”

DIGNITARIES FROM every kingdom in the world came to the palace of Malkata to celebrate Ramesses’s coronation. I stood at the entrance to the Great Hall, where the court took its dinner every night, and admired the glow of a thousand oil lamps as they cast their light across the polished tiles. The chamber was filled with men and women dressed in their finest kilts and beaded gowns.

“Have you ever seen so many people?”

I turned. “Asha!” I exclaimed. “Where have you been?”

“My father wanted me in the stables to prepare—”

“For your time in the military?” I crossed my arms, and when Asha saw that I was truly upset, he smiled disarmingly.

“But I’m here with you now.” He took my arm and led me into the hall. “Have you seen the emissaries who have arrived? I’ll bet you could speak with any one of them.”

“I can’t speak Shasu,” I said, to be contrary.

“But every other language! You could be a vizier if you weren’t a girl.” He glanced across the hall and pointed. “Look!”

I followed his gaze to Pharaoh Seti and Queen Tuya on the royal dais. The queen never went anywhere without Adjo, and the black-and-white dog rested his tapered head on her lap. Although her iwiw had been bred for hunting hare in the marshes, the farthest he ever walked was from his feathered cushion to the water bowl. Now that Ramesses was Pharaoh of Upper Egypt, a third throne had been placed next to his mother.

“So Ramesses will be seated off with his parents,” I said glumly. He had always eaten with me beneath the dais, at the long table filled with the most important members of the court. And now that his chair had been removed, I could see that my own had been placed next to Woserit, the High Priestess of Hathor. Asha saw this as well and shook his head.

“It’s too bad you can’t sit with me. What will you ever talk about with Woserit?”

“Nothing, I suspect.”

“At least they’ve placed you across from Henuttawy. Do you think she might speak with you now?”

All of Thebes was fascinated with Henuttawy, not because she was one of Pharaoh Seti’s two younger sisters, but because there was no one in Egypt with such mesmerizing beauty. Her lips were carefully painted to match the red robes of the goddess Isis, and only the priestesses were allowed to wear that vivid color. As a child of seven I had been fascinated by the way her cloak swirled around her sandals, like water moving gently across the prow of a ship. I had thought at the time that she was the most beautiful woman I would ever see, and tonight I could see that I was still correct. Yet even though we had eaten together at the same table for as long as I could remember, I couldn’t recall a single instance when she had spoken to me. I sighed. “I doubt it.”

“Don’t worry, Nefer.” Asha patted my shoulder the way an older brother might have. “I’m sure you’ll make friends.”

He crossed the hall, and I watched him greet his father at the generals’ table. Soon, I thought, he’ll be one of those men, wearing his braided hair in a small loop at the back of his neck, never going anywhere without his sword.When Asha said something to make his father laugh, I thought of my mother, Queen Mutnodjmet. If she had survived, this would have been her court, filled with her friends, and viziers, and laughter. Women would never dare to whisper about me, for instead of being a spare princess, I’d be the princess.

I took my place next to Woserit, and a prince from Hatti smiled across at me. The three long braids that only Hittites wore fell down his back, and as the guest of honor, his chair had been placed to the right of Henuttawy. Yet no one had remembered the Hittite custom of offering bread to the most important guest first. I took the untouched bowl and passed it to him.

He was about to thank me when Henuttawy placed her slender hand on his arm and announced, “The court of Egypt is honored to host the prince of Hatti as a guest at my nephew’s coronation.”

The viziers, along with everyone at the table, raised their cups, and when the prince made a slow reply in Hittite, Henuttawy laughed. But what the prince said hadn’t been funny. His eyes searched the table for help, and when no one came to his aid, he looked at me.

“He is saying that although this is a happy day,” I translated, “he hopes that Pharaoh Seti will live for many years and not leave the throne of Lower Egypt to Ramesses too soon.”

Henuttawy paled, and at once I saw that I was wrong to have spoken.

“Intelligent girl,” the prince said in broken Egyptian.

But Henuttawy narrowed her eyes. “Intelligent? Even a parrot can learn to imitate.”

“Come, Priestess. Nefertari is quite clever,” Vizier Anemro offered. “No one else remembered to pass bread to the prince when he came to the table.”

“Of course she remembered,” Henuttawy said sharply. “She probably learned it from her aunt. If I recall, the Heretic Queen liked the Hittites so much she invited them to Amarna where they brought us the plague. I’m surprised our brother even allows her to sit among us.”

Woserit frowned. “That was a long time ago. Nefertari can’t help who her aunt was.” She turned to me. “It’s not important,” she said kindly.

“Really?” Henuttawy gloated. “Then why else would Ramesses consider marrying Iset and not our princess?” I lowered my cup, and Henuttawy continued. “Of course, I have no idea what Nefertari will do if she’s not to become a wife of Ramesses. Maybe you could take her in, Woserit.” Henuttawy looked to her younger sister, the High Priestess of the cow goddess Hathor. “I hear that your temple needs some good heifers.”

A few of the courtiers at our table snickered, and Henuttawy looked at me the way a snake looks at its dinner.

Woserit cleared her throat. “I don’t know why our brother puts up with you.”

Henuttawy held out her hand to the Hittite prince, and both of them stood to join the dancing. When the music began, Woserit leaned close to me. “You must be careful around my sister now. Henuttawy has many powerful friends in the palace, and she can ruin you in Thebes if that’s what she wishes.”

“Because I translated for the prince?”

“Because Henuttawy has an interest in seeing Iset become Chief Wife, and there has been talk that this was a role Ramesses might ask you to fill. Given your past, I should say it’s unlikely, but my sister would still be more than happy to see you disappear. If you want to continue to survive in this palace, Nefertari, I suggest you think where your place in it will be. Ramesses’s childhood ended tonight, and your friend Asha will enter the military soon. What will you do? You were born a princess and your mother was a queen. But when your mother died, so did your place in this court. You have no one to guide you, and that’s why you’re allowed to run around wild, hunting with the boys and tugging Ramesses’s hair.”

I flushed. I had thought Woserit was on my side.

“Oh, Pharaoh Seti thinks it is cute,” she admitted. “And you are. But in two years that kind of behavior won’t be so charming. And what will you do when you’re twenty? Or thirty even? When the gold that you’ve inherited is spent, who will support you? Hasn’t Paser ever spoken about this?”

I steadied my lip with my teeth. “No.”

Woserit raised her brows. “None of your tutors?”

I shook my head.

“Then you still have much to learn, no matter how fluent your Hittite.”

THAT EVENING, as I undressed for bed, my nurse remarked on my unusual silence.

“What? Not practicing languages, my lady?” She poured warm water from a pitcher into a bowl, then set out a cloth so I could wash my face.

“What is the point of practicing?” I asked. “When will I use them? Viziers learn languages, not spare princesses. And since a girl can’t be a vizier . . .”

Merit scraped a stool across the tiles and sat next to me. She studied my face in the polished bronze, and no nurse could have been more different from her charge. Her bones were large, whereas mine were small, and Ramesses liked to say that whenever she was angry her neck swelled beneath her chin like a fat pelican’s pouch. She carried her weight in her hips and her breasts, whereas I had no hips and breasts at all. She had been my nurse from the time my mother had died in childbirth, and I loved her as if she were my own mawat. Now, her gaze softened as she guessed at my troubles. “Ah.” She sighed deeply. “This is because Ramesses is going to marry Iset.”

I glanced at her in the mirror. “Then it’s true?”

She shrugged. “There’s been some talk in the palace.” As she shifted her ample bottom on the stool, faience anklets jangled on her feet. “Of course, I had hopes that he was going to marry you.”

“Me?” I thought of Woserit’s words and stared at her. “But why?”

She took back my cloth and wrung it out in the bowl. “Because you are the daughter of a queen, no matter your relationship to the Heretic and his wife.” She was referring to Nefertiti and her husband, Akhenaten, who had banished Egypt’s gods and angered Amun. Their names were never spoken in Thebes. They were simply The Heretics, and even before I had understood what this meant, I had known that it was bad. Now, I tried to imagine Ramesses looking at me with his wide blue eyes, asking me to become his wife, and a warm flush crept over my body. Merit continued, “Your mother would have expected to see you married to a king.”

“And if I don’t marry?” After all, what if Ramesses didn’t feel the same way about me as I felt about him?

“Then you will become a priestess. But you go every day to the Temple of Amun, and you’ve seen how the priestesses live,” she said warningly, motioning for me to stand with her. “There wouldn’t be any fine horses or chariots.”

I raised my arms, and Merit took off my beaded dress. “Even if I were a High Priestess?”

Merit laughed. “Are you already planning for Henuttawy’s death?”

I flushed. “Of course not.”

“Well, you are thirteen. Nearly fourteen. It’s time to decide your place in this palace.”

“Why does everyone keep telling me this tonight?”

“Because a king’s coronation changes everything.”

I put on a fresh sheath, and when I climbed into bed, Merit looked down at me.

“You have eyes like Tefer,” she said tenderly. “They practically glow in the lamplight.” My spotted miw curled closer to me, and when Merit saw us together she smiled. “A pair of green-eyed beauties,” she said.

“Not as beautiful as Iset.”

Merit sat herself on the edge of my bed. “You are the equal of any girl in this palace.”

I rolled my eyes and turned my face away. “You don’t have to pretend. I know I’m nothing like Iset—”

“Iset is three years older than you. In a year or two, you will be a woman and will have grown into your body.”

“Asha says I’ll never grow, that I’ll still be as short as Seti’s dwarfs when I’m twenty.”

Merit pushed her chin inward so that the pelican’s pouch wagged angrily. “And what does Asha think he knows about dwarfs? You will be as tall and beautiful as Isis one day! And if not as tall,” she added cautiously, “then at least as beautiful. What other girl in this palace has eyes like yours? They’re as pretty as your mother’s. And you have your aunt’s smile.”

“I’m nothing like my aunt,” I said angrily.

But then, Merit had been raised in the court of Nefertiti and Akhenaten, so she would know if this were true. Her father had been an important vizier, and Merit had been a nurse to Nefertiti’s children. In the terrible plague that swept through Amarna, Merit lost her family and two of Nefertiti’s daughters in her care. But she never spoke about it to me, and I knew she wished to forget this time twenty years ago. I was sure, as well, that Paser had taught us that the High Priest Rahotep had also served my aunt once, but I was too afraid to confirm this with Merit. This is what my past was like for me. Narrowed eyes, whispering, and uncertainty. I shook my head and murmured, “I am nothing like my aunt.”

Merit raised her brows. “She may have been a heretic,” she whispered, “but she was the greatest beauty who ever walked in Egypt.”

“Prettier than Henuttawy?” I challenged.

“Henuttawy would have been cheap bronze to your aunt’s gold.”

I tried to imagine a face prettier than Henuttawy’s, but couldn’t do it. Secretly I wished that there was an image of Nefertiti left in Thebes. “Do you think that Ramesses will choose Iset because I am related to the Heretic Queen?”

Merit pulled the covers over my chest, prompting a cry of protest from Tefer. “I think that Ramesses will choose Iset because you are thirteen and he is seventeen. But soon, my lady, you will be a woman and ready for whatever future you decide.”

CHAPTER TWO

THREE LINES OF CUNEIFORM

EVERY MORNING for the past seven years I had walked from my chamber in the royal courtyard to the small Temple of Amun by the palace. And there, beneath the limestone pillars, I had giggled with other students of the edduba while Tutor Oba shuffled up the path, using his walking stick like a sword to beat back anyone who stood in his way. Inside, the temple priests would scent our clothes with sacred kyphi, and we would leave smelling of Amun’s daily blessing. Ramesses and Asha would race me to the whitewashed schoolhouse beyond the temple, but yesterday’s coronation changed everything. Now Ramesses would be gone, and Asha would feel too embarrassed to race. He would tell me he was too old for such things. And soon, he would leave me as well.

EVERY MORNING for the past seven years I had walked from my chamber in the royal courtyard to the small Temple of Amun by the palace. And there, beneath the limestone pillars, I had giggled with other students of the edduba while Tutor Oba shuffled up the path, using his walking stick like a sword to beat back anyone who stood in his way. Inside, the temple priests would scent our clothes with sacred kyphi, and we would leave smelling of Amun’s daily blessing. Ramesses and Asha would race me to the whitewashed schoolhouse beyond the temple, but yesterday’s coronation changed everything. Now Ramesses would be gone, and Asha would feel too embarrassed to race. He would tell me he was too old for such things. And soon, he would leave me as well.

When Merit appeared in my chamber, I followed her glumly into my robing room, lifting my arms while she fastened a linen belt around my kilt.

“Myrtle or fenugreek today, my lady?”

I shrugged. “I don’t care.”

She frowned at me and fetched the myrtle cream. She opened the alabaster jar with a twist, then spread the thick cream over my cheeks. “Stop making that face,” she reprimanded.

“What face?”

“The one like Bes.”

I suppressed a smile. Bes was the dwarf god of childbirth; his hideous grimace scared Anubis from dragging newborn children away to the Afterlife.

“I don’t know what you have to sulk about,” Merit said. “You won’t be alone. There’s an entire edduba full of students.”

“And they’re only nice to me because of Ramesses. Asha and Ramesses are my only real friends. None of the girls will go hunting or swimming.”

“Then it’s lucky for you that Asha is still in the edduba.”

“For now.” I took my schoolbag grudgingly, and as Merit saw me off from my chamber she called, “Scowling like Bes will only scare him away sooner!”

But I wasn’t in the mood for her humor. I took the longest path to the edduba, through the eastern passageway into the shadowed courtyards at the rear of the palace, then along the crescent of temples and barracks that separated Malkata from the hills beyond. I have often heard the palace compared to a pearl, perfectly protected within its shell. On one side are the sandstone cliffs, on the other is the lake that had been carved by my akhu to allow boats to travel from the River Nile to the very steps of the Audience Chamber. Amunhotep III built it for his wife, Queen Tiye. When his architects had said that such a thing could never be made, he designed it himself. With his legacy before me, I walked slowly around the Arena, past the barracks with their dusty parade grounds, and then beyond the servants’ quarters that squatted back into the wadis to the west. When I came to the lakeshore, I approached the water to peer at my reflection.

I don’t look anything like Bes, I thought. For one, he has a much bigger nose than I do. I made the grimace that all artists carve on statues of Bes, and behind me someone laughed.

“Are you admiring your teeth?” Asha cried. “What kind of face was that?”

I glared at him. “Merit says I have a face like Bes.”

Asha stepped back to scrutinize me. “Yes, I can see the resemblance. You both have big cheeks, and you are rather short.”

“Stop it!”

“I wasn’t the one making the face!” We continued our walk to the temple and he asked, “So did Merit tell you the news last night? Ramesses will probably marry Iset.”

I looked away and didn’t reply. In the heat of Thoth, the sun cast its rays across the lake like a golden fisherman’s net. “If Ramesses was going to be married,” I said finally, “why wouldn’t he tell us about it himself?”

“Perhaps he isn’t certain. After all, it’s Pharaoh Seti who will ultimately decide.”

“But she isn’t a match for Ramesses at all! She doesn’t hunt, or swim, or play Senet. She can’t even read Hittite!”

Tutor Oba glared as we approached the courtyard, and under his breath Asha whispered, “Prepare for it!”

“How nice of the two of you to join us!” Oba exclaimed. Two hundred faces turned in our direction, and Tutor Oba lashed out at Asha with his stick. “Get in line!” He caught Asha on the back of the leg, and we scampered to join the other students. “Do you think that Ra appears in his solar bark when he feels like it? Of course not! He’s on time. Every sunrise he’s on time!”

Asha glanced over his shoulder at me in line as we followed Tutor Oba into the sanctuary. Cloth mats had been spread out for us on the floor, and we took our seats and waited for the priests. I whispered to Asha, “I’ll bet Ramesses is sitting in the Audience Chamber right now, wishing he was with us.”

“I don’t know. He’s safe from Tutor Oba.”

I snickered as seven priests entered the chamber, swinging incense from bronze holders and intoning the morning hymn to Amun.

Hail to thee, Amun-Ra, Lord of the thrones of the earth, the oldest existence, ancient of heaven, support of all things.Chief of the gods, lord of truth; maker of all things above and below.Hail to thee.

As the incense filled the room, a student coughed. Tutor Oba turned around to look fiercely at him and I elbowed Asha in the side, bent my mouth into a mean, angry line, then imitated Oba’s snarling. One of the students laughed out loud, and Tutor Oba twisted around. “Asha and Princess Nefertari!” he snapped.

Asha glared at me and I giggled. But outside the temple, I didn’t ask him to race me to the edduba.

“I don’t know why the priests don’t throw us out,” he said.

I grinned. “Because we’re royalty.”

“You’re royalty,” Asha countered. “I’m the son of a soldier.”

“You mean the son of a general.”

“Still, I’m not like you. I don’t have a chamber in the palace or a body servant. I need to be careful.”

“But it was funny,” I prompted.

“A little,” he admitted as we reached the low white walls of the royal edduba. The schoolhouse squatted like a fat goose on the hillside, and Asha’s footsteps slowed as we approached its open doors. “So what do you think it’ll be today?” he asked.

“Probably cuneiform.”

He sighed heavily. “I can’t afford another poor report to my father.”

“Take the reed mat next to mine, and I’ll write big enough for you to see,” I promised.

Inside the halls of the edduba, students called to one another, laughing and exchanging stories until the trumpet sounded for class. Paser stood at the front of our chamber, observing the chaos, but when Iset entered, the room grew silent. She moved through the students, and they parted before her as if a giant hand had pushed them aside. She sat across from me, folding her long legs on her reed mat the way she always did, but this time, when she swept back her dark hair, her fingers seemed fascinating to me. They were long and tapered. At court, only Henuttawy surpassed Iset’s skill with the harp. Was that why Pharaoh Seti thought she’d make a good wife?

“We may all stop staring now,” Paser announced. “Let us take out our ink. Today, we translate two of the Hittite emperor’s letters to Pharaoh Seti. As you know, Hittite is written in cuneiform, which will mean transcribing every word from cuneiform to hieroglyphics.”

I took out several reed pens and ink from my bag. When the basket of blank papyrus came to me, I took the smoothest one from the pile. Outside the edduba a trumpet blared again, and the noise from the other classrooms went silent. Paser passed out copies of Emperor Muwatallis’s first letter, and in the early morning heat the sound of pens scratching on papyrus settled upon the room. The air felt heavy, and sweat beaded behind my knees where I sat cross-legged. Two fan bearers from the palace cooled the room with their long blades, and as the air stirred, Iset’s perfume moved across the chamber to tickle my nose. She told the students she wore it to cover the unbearable smell of the ink, which is made from ash and the fat boiled off a donkey’s skin. But I knew this wasn’t true. Palace scribes mixed our ink with musk oil to cover the terrible scent. What she really wanted was to attract attention. I wrinkled my nose and refused to be distracted. The important information in the letter had been removed, and what had been left was simple to translate. I wrote several lines in large hieroglyphics on my papyrus, and when I’d finished with the letter, Paser cleared his throat.

“The scribes should be done with the translation of Emperor Muwatallis’s second letter. When I return, we will move on,” he warned sternly. The students waited until the sound of his sandals had faded before turning to me.

“Do you understand this, Nefer?” Asha pointed to the sixth line.

“And what about this?” Baki, Vizier Anemro’s son, couldn’t make out the third. He held out his scroll and the class waited.

“To the Pharaoh of Egypt, who is wealthy in land and great in strength. It is like all of his other letters.” I shrugged. “It begins with flattery and ends with a threat.”

“And what about this?” someone else asked. The students gathered around me and I translated the words quickly for them. When I glanced at Iset, I saw that her first line wasn’t finished. “Do you need help?”

“Why would I need help?” She pushed aside her scroll. “You haven’t heard?”

“You’re about to become wife to Pharaoh Ramesses,” I said flatly.

Iset stood. “You think that because I wasn’t born a princess like you that I’ll spend my life weaving linen in the harem?”

She wasn’t speaking about the harem of Mi-Wer in the Fayyum, where Pharaoh’s least important wives are kept. She was speaking about the harem behind the edduba, where Seti housed the women of previous kings and those whom he himself had chosen. Iset’s grandmother had been one of Pharaoh Horemheb’s wives. I had heard that one day he saw her walking along the riverbank, collecting shells for her own husband’s funeral. She was already pregnant with her only child, but just as that had not stopped him from taking my mother, Horemheb wanted her as his bride. So Iset was not related to a Pharaoh at all, but to a long line of women who had lived, and fished, and made their work on the River Nile. “I may be an orphan of the harem,” she went on, “but I think everyone here would agree that being the niece of a heretic is much worse, whatever your fat nurse likes to pretend. And no one in this edduba likes you,” she revealed. “They smile at you because of Ramesses, and now that he’s gone they only go on smiling and laughing because you help them.”

“That’s a lie!” Asha stood up angrily. “No one here feels that way.”

I looked around, but none of the other students came to my defense, and a shamed heat crept into my cheeks.

Iset smirked. “You may think you’re great friends with Ramesses, hunting and swimming in the lake together, but he’s marrying me. And I’ve already consulted with the priests,” she said. “They’ve given me a charm for every possible event.”

Asha exclaimed, “Do you think Nefertari is going to try and give you the evil eye?”

The other students in the edduba laughed, and Iset drew herself up to her fullest height. “She can try! All of you can try,” she said viciously. “It won’t make any difference. I’m wasting my time in this edduba now.”

“You certainly are.” A shadow darkened the doorway, then Henuttawy appeared in her red robes of Isis. She glanced across the room at us, and a lion could not have looked at a mouse with any less interest. “Where is your tutor?” she demanded.

Iset moved quickly to the side of the High Priestess, and I noticed that she had begun to paint her eyes the same way that Henuttawy did, with long sweeps of kohl extending to her temples. “Gone to see the scribes,” she answered eagerly.

Henuttawy hesitated. She walked over to my reed mat and looked down. “Princess Nefertari. Still studying your hieroglyphs?”

“No. I’m studying my cuneiform.”

Asha laughed, and Henuttawy’s gaze flicked to him. But he was taller than the other boys, and there was an intelligence in his glare that unnerved her. She turned back to me. “I don’t know why you waste your time, especially when you’ll only become a priestess in a run-down temple like Hathor’s.”

“As always, it is charming to see you, my lady.” Our tutor had returned with a handful of scrolls. He laid them on a low table, as Henuttawy turned to face him.

“Ah, Paser. I was just telling Princess Nefertari to be diligent in her studies. Unfortunately, Iset does not have time for that anymore.”

“What a shame,” Paser replied, looking at Iset’s discarded papyrus. “Today, I believe she was going to progress to three lines of cuneiform.”

The students snickered, and Henuttawy hurried from the edduba with Iset in tow.

“There is no cause for laughing,” Paser said sharply, and the room fell silent. “We may all go back to our translations now. When you are finished, come to the front of the room and bring your papyrus. Then you may begin work on Emperor Muwatallis’s second letter.”

I tried to concentrate, but tears blurred my vision. I didn’t want anyone to see how much Iset’s words had hurt, so I kept my head low, even when Baki made a hissing noise at me. He wants help now, I thought. But would he even glance at me outside the edduba?

I finished my translation and approached Paser, handing him my sheet.

He smiled approvingly. “Excellent, as always.” I glanced back at the other students and wondered if I detected resentment in their eyes. “I must warn you about this next letter, however. There is an unflattering reference to your aunt.”

“Why should I care? I’m nothing like her,” I said defensively.

“I wanted to be sure you understood. It seems the scribes forgot to take it out.”

“She was a heretic,” I said, “and whatever words the emperor has for her, I am sure they are justified.”

I returned to my reed mat, then skimmed the letter, searching for familiar names. Nefertiti was mentioned at the bottom of the papyrus, and so was my mother. I held my breath as I read Emperor Muwatallis’s words.

You threaten us with war, but our god Teshub has watched over Hatti for a thousand years, while your gods were banished by Pharaoh Akhenaten. What makes you think that they have forgiven his heresy? It may be that Sekhmet, your goddess of war, has abandoned you completely. And what of Mutnodjmet, Nefertiti’s sister? Your people allowed her to become a queen when all of Egypt knows she serviced your Heretic King in his temple as well as his private chamber. Do you really think your gods have forgiven this? Will you risk war with us when we have treated our own gods with respect?

I glanced up at Paser, and in his expression seemed to flicker a trace of regret. But I would never be pitied. Clenching the reed pen in my hand, I wrote as quickly and firmly as I could, and when a tear smeared the ink on my papyrus, I blotted it away with sand.

WHILE COURTIERS filled the Great Hall that evening, Asha and I waited on a corner of the balcony, whispering to each other about what had happened in the edduba. The setting sun crowned his head in a soft glow, and the braid he wore over his shoulder was nearly as long as mine. I sat forward on the limestone balustrade looking at him. “Have you ever heard Iset so angry?”

“No, but I’ve never heard her say much at all,” he admitted.

“She’s been with us for seven years!”

“All she does is giggle with those harem girls who wait for her outside.”

“She certainly wouldn’t like it if she heard you say that,” I warned.

Asha shrugged. “It doesn’t seem she likes much of anything. And certainly not you—”

“And what have I ever done to her?” I exclaimed.

But Asha was saved from answering when Ramesses burst through the double doors.

“There you are!” he called across to us, and Asha said quickly, “Don’t say anything about Iset. Ramesses will only think we’re jealous.”

Ramesses looked between the two of us. “Where have both of you been?”

“Where have you been?” Asha countered. “We haven’t seen you since your coronation.”

“We thought we might not ever see you again,” I added, a little more plaintively than intended.

Ramesses embraced me. “I would never leave my little sister behind.”

“How about your charioteer?”

At once, Ramesses let go of me. “It’s done then?” he exclaimed, and Asha said smugly, “Just a few hours ago. Tomorrow I begin my training to be an officer of Pharaoh’s charioteers.”

I inhaled sharply. “And you didn’t tell me?”

“I was waiting to tell you both!”

Ramesses gave Asha a congratulatory slap on the back, but I cried, “Now I’ll be the only one left at the edduba with Paser!”

“Come,” Ramesses said, placating me. “Don’t be upset.”

“Why not?” I complained. “Asha is going to the army and you’re getting married to Iset!”

Asha and I both looked at Ramesses to see if it was true.

“My father is going to announce it tonight. He feels she’ll make a good wife.”

“But do you?” I asked.

“I worry about her skills,” he admitted. “You’ve seen her in Paser’s class. But Henuttawy thinks I should make her Chief Wife.”

“Pharaohs don’t choose a Chief Wife until they’re eighteen!” I blurted.

Ramesses studied me, and I colored at my outburst. “So what is that?” I changed the subject and pointed to the jeweled case he was carrying.

“A sword.” He opened the case to produce an arm-length blade.

Asha was impressed. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” he admitted.

“It’s Hittite, made of something they call iron. It’s said to be even stronger than bronze.” The weapon had a sharper curve than anything I had seen before, and from the designs carefully etched onto its hilt, I imagined that its cost had been great.

Ramesses handed the weapon to Asha, who held it up to the light. “Who gave this to you?”

“My father, for my coronation.”

Asha handed the iron blade to me, and I gripped the hilt in my palm. “You could use this to decapitate Muwatallis!”

Ramesses laughed. “Or at least his son, Urhi.”

Asha looked between us.

“The emperor of the Hittites,” I explained. “When he dies, his son, Urhi, will succeed him.”

“Asha doesn’t care about politics,” Ramesses said. “But ask him anything about horses and chariots . . .”

The double doors to the balcony swung open, and Iset fixed us instantly in her gaze. Her beaded wig was adorned with charms, and a talented body servant had dusted the kohl beneath her eyes with small flecks of gold.

“The three inseparables,” she said, smiling.

I realized how much she sounded like Henuttawy. She crossed the balcony, and I wondered where she’d gotten the deben to afford sandals with lapis jewels. What gold had been left when Iset’s mother died had long since been spent educating her.

“What is this?” She looked down at the sword I had returned to Ramesses.

“For war,” Ramesses explained. “Would you like to watch? I’m going to show Asha and Nefer how it cuts.”

Iset frowned prettily. “But the cupbearer has already poured your father’s wine.”

Ramesses hesitated. He breathed in her perfume, and I could see how he was affected by her closeness. Her sheath was tight over her curves and exposed her beautifully hennaed breasts. Then I noticed the gold and carnelian necklace at her throat. She was wearing Queen Tuya’s jewels. The queen, who had watched me play with Ramesses since we were children, had given her favorite necklace to Iset.

Ramesses glanced across at Asha, and then at me.

“Some other time,” Asha said helpfully, and Iset took Ramesses’s arm. We watched as they left the balcony together, and I turned to Asha.

“Did you see what she was wearing?”

“Queen Tuya’s own jewels,” he said with resignation.

“But why would Ramesses choose a wife like Iset? So she’s pretty. What does that matter when she doesn’t speak Hittite or even write cuneiform?”

“It matters because Pharaoh needs a wife,” Asha said grimly. “You know, he might have chosen you—if not for your family.”

It was as though someone had crushed the air from my chest. I followed him into the Great Hall, and that evening, when the marriage was formally announced, I felt I was losing something I would never get back. Yet neither of Iset’s parents were there to see her triumph. Her father was unknown, and this would have been a great scandal for Iset’s mother had she lived through childbirth. So the herald announced her grandmother’s name instead; for she had raised Iset and had once been a part of Pharaoh Horemheb’s harem. She had been dead for a year, but this was the proper thing to do.

When the feast was finally over, I returned to my chamber off the royal courtyard and sat quietly at my mother’s ebony table. Merit wiped the kohl from my eyes and the red ochre from my lips, then she handed me a cone of incense and watched as I knelt before my mother’s naos. Some naoi are large and granite, with an opening in the center to place a statue of a god and a ledge on which to burn incense. My naos, however, was small and wooden. It was a shrine my mother had owned as a girl, and perhaps even her mother before her. When I kneeled, it only came up to my chest, and inside the wooden doors was a statue of Mut, after whom my mother had been named. While the feline goddess regarded me with her cat eyes, I blinked away tears.

“What would have happened if my mother had lived?” I asked Merit.

My nurse sat on the corner of the bed. “I don’t know, my lady. But remember the many hardships that she endured. In the fire your mother lost everyone she loved.”

The chambers in Malkata to which the fire had spread had never been rebuilt. The blackened stones and charred remains of wooden tables still stood beyond the royal courtyard, reclaimed by vines and untended weeds. When I was seven, I had insisted that Merit take me there, and when we arrived I’d stood frozen to the spot, trying to imagine where my father had been when the flames broke out. Merit said it was an oil lamp that had fallen, but I had heard the viziers speak of something darker, of a plot to kill my grandfather, the Pharaoh Ay. Behind those walls, my entire family had vanished in the flames: my brother, my father, my grandfather and his queen. Only my mother survived because she had been in the gardens. And when General Horemheb heard that Ay was dead, he came to the palace with the army behind him and forced my mother into marriage. For she had been the last royal link to the throne. I wondered if Horemheb felt any guilt at all when she too embraced Osiris, still crying out my father’s name. Sometimes, I thought of her last weeks on earth. Just as my ka was being formed by Khnum on his potter’s wheel, hers had been flying away.

I looked over my shoulder at Merit, watching me with unhappy eyes. She didn’t like when I asked questions about my mother, but she never refused to answer them. “And when she died,” I asked, even though I already knew the answer, “who did she cry out for?”

Merit’s face grew solemn. “Your father. And—”

I turned, forgetting about the cone of incense. “And?”

“And her sister,” she admitted.

My eyes widened. “You’ve never said that before!”

“Because it’s nothing you needed to know,” Merit said quickly.

“But was she truly a heretic, as they say?”

“My lady—”

I saw that Merit was going to put off my question, and I shook my head firmly. “I was named for Nefertiti. My mother couldn’t have believed that her sister was a heretic.”

No one spoke the name of Nefertiti in the palace, and Merit pressed her lips together to keep from reprimanding me. She unfolded her hands and her gaze grew distant. “It was not so much the Pharaoh-Queen herself, as her husband.”

“Akhenaten?”

Merit shifted uncomfortably. “Yes. He banished the gods. He destroyed the temples of Amun and replaced the statues of Ra with ones of himself.”

“And my aunt?”

“She filled the streets with her image.”

“In place of the gods?”

“Yes.”

“But then where have they gone? I have never even seen a likeness of them.”

“Of course not!” Merit stood. “Everything that belonged to your aunt was destroyed.”

“Even my mother’s name,” I said and looked back at the shrine. Incense drifted across the face of the feline goddess. When she died, Horemheb had taken everything. “It’s as though I’ve been born with no akhu,” I said. “No ancestors at all. Did you know that in the edduba,” I confided, “students don’t learn about Nefertiti’s reign, or the reign of Pharaoh Ay, or Tutankhamun?”

Merit nodded. “Yes. Horemheb erased their names from the scrolls.”

“He took their lives. He ruled for four years, but they teach us that he ruled for dozens and dozens. I know better. Ramesses knows better. But what will my children be taught? For them, my family will never have existed.”

Each year, on the Feast of Wag, Egyptians visit the mortuary temples of their ancestors. But there was nowhere for me to honor my own mother’s ka or the ka of my father with incense or a bowl of oil. Even their tombs had been hidden in the hills of Thebes, safe from the Aten priests and Horemheb’s vengeance. “Who will remember them, Merit? Who?”

Merit placed her palm on my shoulder. “You.”

“And when I’m gone?”

“Make sure you are never gone from the people’s memory. And those who know of your fame will search out your past and find Pharaoh Ay and Queen Mutnodjmet.”

“Otherwise they will be erased.”

“And Horemheb will have succeeded.”

CHAPTER THREE

THE WAY A CAT LISTENS

THE HIGH PRIESTS divined that Ramesses should marry on the twelfth of Thoth. They had chosen it as the most auspicious day in the season of Akhet, and when I walked from the palace to the Temple of Amun, the lake was already crowded with vessels bringing food and gifts for the celebration.

THE HIGH PRIESTS divined that Ramesses should marry on the twelfth of Thoth. They had chosen it as the most auspicious day in the season of Akhet, and when I walked from the palace to the Temple of Amun, the lake was already crowded with vessels bringing food and gifts for the celebration.

Inside the temple I kept to myself, and not even Tutor Oba could find fault with me when the priests were finished. “What’s the matter, Princess? No one to entertain now that Pharaoh Ramesses and Asha are gone?”

I looked up into Tutor Oba’s wrinkled face. His skin was like papyrus; every part of it was lined. Even around his nose there were creases. I suppose he was only fifty, but he seemed to me to be as old as the cracking paint in my chamber.

“Yes, everybody has left me,” I said.

Tutor Oba laughed, but it wasn’t a pleasant sound.

“Everybody has left you!” he repeated. “Everybody.” He looked around him at the two hundred students who were following him to the edduba. “Tutor Paser tells me you are a very good student, and now I wonder if he means in acting or in languages. Perhaps in a few years, we’ll be seeing you in one of Pharaoh’s performances!”

I walked the rest of the way to the edduba in silence. Behind me, I could still hear Tutor Oba’s grating laugh, and inside the class I was too angry to care when Paser announced, “Today, we will begin a new language.”

I don’t remember what I learned that day, or how Paser began to teach us the language of Shasu. Instead of paying attention, I stared at the girl on the reed mat to my left. She was no more than eight or nine, but she was sitting at the front of the class where Asha should have been. When the time came for our afternoon meal, she ran away with another girl her age, and it occurred to me that I no longer had anyone to eat with.

“Who’s in for dice?” Baki announced, between mouthfuls.

“I’ll play,” I said.

Baki looked behind him to a group of boys, and their faces were all set against me. “I . . . don’t think we allow girls to play.”

“You allow girls every other day,” I said.

“But . . . but not today.”

The other boys nodded, and shame brightened my cheeks. I stepped into the courtyard to find a seat by myself, then recognized Asha on the stone bench where we always ate.

“Asha! What are you doing here?” I exclaimed.

He leaned his yew bow against the bench. “Soldiers get mealtimes, too,” he said. He searched my face. “What’s the matter?”

I shrugged. “The boys won’t allow me to play dice with them.”

“Which boys?” he demanded.

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It does matter.” His voice grew menacing. “Which ones?”

“Baki,” I said, and when Asha rose threateningly from the bench, I pulled him back. “It’s not just him, it’s everyone, Asha. Iset was right. They were friendly to me because of you and Ramesses, and now that you’re both gone, I’m just a leftover princess from a dynasty of heretics.” I raised my chin and refused to be upset. “So what is it like to be a charioteer?”

Asha sat back and studied my face, but I didn’t need his sympathy. “Wonderful,” he admitted, and opened his sack. “No cuneiform, no hieroglyphics, no translating Muwatallis’s endless threats.” He looked to the sky and his smile was genuine. “I’ve always known I was meant to be in Pharaoh’s army. I was never really good at all that.” He indicated the edduba with his thumb.

“But your father wants you to be Master of the Charioteers. You have to be educated!”

“And thankfully that’s over.” He took out a honey cake and gave half to me. “So did you see the number of merchants that have arrived? The palace is filled with them. We couldn’t take the horses to the lake because it’s crowded with foreign vessels.”

“Then let’s go to the quay and see what’s happening!”

Asha glanced around him, but the other students were rolling knucklebones and playing Senet. “Nefer, we don’t have time for that.”

“Why not? Paser is always late, and the soldiers don’t return until the trumpets call them back. That’s long after Paser begins. When will we ever see so many ships? And think of the animals they might be bringing. Horses,” I said temptingly. “Maybe from Hatti.”

I had said the right words. He stood with me, and when we reached the lake, we saw a dozen ships lying at anchor. Above us on the dock, pennants of every color snapped in the breeze, their rich cloth catching the light like brightly painted jewels. Heavy chests were being unloaded, and just as I had guessed, horses had arrived, gifts from the kingdom of Hatti.

“You were right!” Asha exclaimed. “How did you know?”

“Because every kingdom will send gifts. What else do the Hittites have that we’d want?”

The air filled with the shouts of merchants and the stamps of sea-weary horses skittering down the gang-planks. We picked our way toward them through the bales and bustle. Asha reached out to stroke an ink-black mare, but the man in charge chided him angrily in Hittite.

“You are speaking with Pharaoh’s closest friend,” I said sharply. “He has come to inspect the gifts.”

“You speak Hittite?” the merchant demanded.

I nodded. “Yes,” I replied in his language. “And this is Asha, future Master of Pharaoh’s Charioteers.”

The Hittite merchant narrowed his eyes, trying to determine if he believed me. Finally, he gave a judicious nod. “Good. You may instruct him to lead these horses to Pharaoh’s stables.”

I smiled widely at Asha.

“What? What is he saying?”

“He wants you to take the horses to Pharaoh Seti’s stables.”

“Me?” Asha exclaimed. “No! Tell him—”

I smiled at the merchant. “He will be more than happy to deliver Hatti’s gifts.”

Asha stared at me. “Did you tell him no?”

“Of course not! What’s the matter with delivering a few horses?”

“Because how will I explain what I’m doing?” Asha cried.

I looked at him. “You were passing by on the way to the palace. You were asked to do this task because you are knowledgeable about horses.” I turned back to the merchant. “Before we take these horses from Hatti, we would like to inspect the other gifts.”

“What? What did you tell him now?”

“Trust me, Asha! There is such a thing as being too cautious.”

The merchant frowned, Asha held his breath, and I gave the old man my most impatient look. He sighed heavily, but eventually he led us across the quay, past exquisitely carved chests made from ivory and holding a fortune in cinnamon and myrrh. The rich scents mingled with the muddy tang of the river. Asha pointed ahead to a long leather box. “Ask him what’s in there!”

The old man caught Asha’s meaning, and he bent down to open the leather case. His long hair spilled over his shoulder; he tossed his three white braids behind him and pulled out a gleaming metal sword.

I glanced at Asha. “Iron,” I whispered.

Asha reached out and turned the hilt, so that the long blade caught the summer’s light just as it had on the balcony with Ramesses.

“How many are there?” Asha gestured.

The merchant seemed to understand, because he answered, “Two. One for each Pharaoh.”

I translated his answer, and as Asha returned the weapon, a pair of ebony oars caught my eye. “And what are those for?” I pointed to the paddles.

For the first time, the old man smiled. “Pharaoh Ramesses himself—for his marriage ceremony.”

The tapered paddles had been carved into the heads of sleeping ducks, and he caressed the ebony heads as if the feathers were real. “His Highness will use them to row across the lake while the rest of the court follows behind him in vessels of their own.”

I imagined Ramesses using the oars to paddle closer to Iset as she sailed in front of him, her dark hair covered by a beaded net whose lapis stones would catch at the light. Asha and I would have to sail behind them, and there would be no question of my calling out to Ramesses or tugging his hair. Perhaps if I had acted less like a child at Ramesses’s coronation, I might have been the one in the boat before him. Then, it would be me he would turn to at night, sharing the day’s stories with his irresistible laugh.

I followed Asha to the stables in silence, and that evening, when Merit instructed me to change from my short sheath into a proper kilt for the night, I didn’t complain. I let her place a silver pectoral around my neck and sat still while she rubbed myrtle cream into my cheeks.

“How come you’re so eager to do as I say?” she asked suspiciously.

I flushed. “Don’t I always?”

The pelican’s pouch lengthened as Merit pushed in her chin. “A dog does what its master says. You listen the way a cat listens.”

We both looked at Tefer reclining on the bed, and the untamable miw placed his ears against his head as if he knew he was being chastised.

“Now that Pharaoh Ramesses has grown up, have you decided to grow up as well?” Merit challenged.

“Perhaps.”

WHEN IT was time to eat in the Great Hall, I took my place beneath the dais and could see that Ramesses was watching Iset. In ten days she would become his wife, and I wondered if he would forget about me entirely.

Pharaoh Seti stood from his throne, and as he raised his arms the hall fell silent. “Shall we have some music?” he asked loudly, and next to him Queen Tuya nodded. As always, her brow appeared damp with sweat, and I wondered how such a large woman could bear living in the terrible heat of Thebes. She didn’t bother to stand, and fan bearers with their long ostrich feathers stirred the perfumed air around her so that even from the table beneath the dais it was possible to smell her lavender and lotus blossom.

“Why don’t we hear from the future Queen of Egypt?” she suggested, and the entire court looked to Iset, who rose gracefully from her chair.

“As Your Highnesses wish.”

Iset made a pretty bow and slowly crossed the chamber. As she approached the harp that had been placed beneath the dais, Ramesses smiled. He watched her arrange herself before the instrument, pressing the carved wooden shoulder between her breasts, and as the lilting notes echoed across the hall, a vizier behind me murmured, “Beautiful. Exceptionally beautiful.”

“The music or the girl?” Vizier Anemro asked.

The men at the table all snickered.

ON THE eve of Ramesses’s marriage to Iset, Tutor Paser called me aside while the other students ran home. He stood at the front of the classroom, surrounded by baskets of papyrus and fresh reed pens. In the soft light of the afternoon, I realized he was not as old as I had often imagined him to be. His dark hair was pulled into a looser braid, and his eyes seemed kinder than they had ever been. But when he motioned for me to sit in the chair across from him, tears of shame blurred my vision before he even said a word.

“Despite the fact that your nurse allows you to run around the palace like a wild child of Set,” he began, “you have always been the best student in this edduba. But in the past ten days you’ve missed six times, and today the translations you completed could have been done by a laborer in one of Pharaoh’s tombs.”

I lowered my head. “I will do better,” I promised.

“Merit tells me you don’t practice your languages anymore. That you are distracted. Is this because of Ramesses’s marriage to Iset?”

I raised my eyes and wiped away my tears with the back of my hand. “Without Ramesses here, no one wants to be near me! All of the students in the edduba pretended to be kind to me because of Ramesses. Now that he’s gone they call me a Heretic Princess.”

Paser leaned forward, frowning. “Who has called you this?”

“Iset,” I whispered.

“That is only one person.”

“But the rest of them think it! I know they do. And in the Great Hall, when the High Priest sits at our table beneath the dais . . .”

“I would not concern myself with what Rahotep thinks. You know that his father was the High Priest of Amun—”

“And when my aunt became queen, she and Pharaoh Akhenaten had him killed. I know that. So Iset is against me, and the High Priest is against me, and even Queen Tuya . . .” I choked back a sob. “They are all against me because of my family. Why did my mother name me for a heretic?” I cried.

Paser shifted uncomfortably. “She could never have known the hatred that people would still have for her sister twenty-five years later.”

He stood and offered me his hand. “Nefertari, you must continue to study your Hittite and Shasu. Whatever happens with Pharaoh Ramesses and Asha, you must excel in this edduba. It will be the only way to find a place for yourself in the palace.”

“As what?” I asked desperately. “A woman can’t be a vizier.”

“No,” Paser said. “But you are a princess. With your command of languages there are a dozen different futures for you. As a High Priestess, or a High Priestess’s scribe, possibly even as an emissary.”Paser reached into a basket and produced several scrolls. “Letters from King Muwatallis to Pharaoh Seti. Work you missed while you were in the palace pretending to be sick.”

I’m sure my cheeks turned a brilliant scarlet, but as I left, I reminded myself of the truth in Paser’s words. I am a princess. I am the daughter and niece and granddaughter of queens. There are many possible futures for me.

When I returned to the courtyard of the palace, a large pavilion of white cloth had been erected where Ramesses’s most important marriage guests would feast. Hundreds of servants scurried like ants, rushing from the Great Hall into the tent with chairs and tables held high above their heads. Beneath a golden sunshade, away from the chaos, Pharaoh Seti’s sisters had arrived to oversee the preparations. Iset was there, too, with her friends from the harem.

“Nefer!” Ramesses called from across the courtyard. He left Iset to hurry over to me. He had taken off his nemes crown in the heat, and the summer sun set his hair aflame. I imagined Iset running her fingers through the red-gold tresses, whispering in his ear the way Henuttawy whispered to handsome noblemen whenever she was drunk.

“I haven’t seen you in days,” he said apologetically. “You can’t imagine what it’s been like in the Audience Chamber. Every day it’s another crisis. Do you remember last year how the lake receded?”

I nodded. Ramesses shaded his eyes with his hand. “Well, that’s because the Nile didn’t overflow its banks. And without an overflow to water the land, very little was harvested this summer. In some cities it’s already led to famine.”

“Not in Thebes,” I protested.

“No, but in the rest of Upper Egypt,” he said.

I tried to imagine a famine when tomorrow the palace would feed a thousand people. Cuts of beef, roasted duck, and lamb were already being prepared in the kitchens, and wide barrels of pomegranate wine were waiting in the Great Hall to be rolled into the pavilion.

Ramesses caught my glance and nodded. “I know it’s hard to believe,” he said, “but the people outside of Thebes are suffering. We’ve had a little rain, but not cities like Edfu and Aswan.”

“So will Thebes share its grain?”

“Only if there’s enough. The viziers are angry that the Habiru are growing so plentiful in Egypt. They say there are nearly six hundred thousand of them, and in a time when there’s not enough food for Egyptians, some of my father’s men are saying that measures must be taken.”

“What kind of measures?”

Ramesses looked away.

“What kind of measures?” I repeated.

“Measures to be sure that there are no more Habiru sons—”

I gasped. “What? You wouldn’t allow—”

“Of course not! But the viziers are talking. They’re saying it’s not just their numbers,” Ramesses explained. “Rahotep believes that if the sons are killed, the Habiru daughters will marry Egyptians to become like us.”

“They are like us! Tutor Amos is a Habiru and his people have been here for a hundred years. My grandfather brought the Habiru to Thebes when he conquered Canaan—”

“But Rahotep is telling the court that the Habiru worship one god like the Heretic King.” Ramesses lowered his voice so that none of the servants who were passing could hear him. “He thinks they’re heretics, Nefer.”

“Of course he would say that! He was a heretic himself—a High Priest of Aten. Now he wants to show the court that he’s loyal to Amun.”

Ramesses nodded. “That’s what I told my father.”

“And what does he say?”

“That a sixth of his army is Habiru. Their sons fight alongside Egyptian sons. But the people are growing angrier, Nefer, and every day it’s something different. Droughts, or poor trade, or pirates in the Northern Sea. Now everything has to stop while hundreds of dignitaries arrive and you should see the preparations. When an Assyrian prince came this morning, Vizier Anemro gave him a room that faced west.”

I covered my mouth. “He didn’t know that Assyrians sleep facing the rising sun?”

“No. I had to explain it to him. He moved the prince’s chamber, but the Assyrians were already angry. None of this would have happened if Paser had simply agreed to be vizier.”

“Tutor Paser?”

“My father has already asked him twice. He’d be the youngest vizier in Egypt, but surely the most intelligent.”

“And both times he declined?”

Ramesses nodded. “I can’t understand it.” He looked down at the scrolls I was carrying. “What are these?” There was a glint in Ramesses’s eyes, as if he was tired of talking about his wedding and politics. “It looks like several days’ worth of work to me,” he said, and snatched one of the scrolls. “Have you been missing classes?”

“Give it back!” I cried. “I was sick.”

I made a grab for the papyrus but Ramesses held it higher.

“If you want it,” he teased, “you’re going to have to catch it!”

He sprinted across the courtyard, and with my arms full of scrolls, I gave chase. Then a shadow loomed across the stones and he stopped.

“What are you doing?” Henuttawy demanded. The red robes of Isis swirled at her feet. She snatched the scroll that Ramesses had taken and shoved it at me. “You are a king of Egypt,” she reminded him sharply, and her nephew flushed. “Do you realize that you have left Iset all alone to decide which instruments shall be played at the feast?”

The three of us looked across the courtyard at Iset, who didn’t seem all alone to me. She and her friends were huddled together, whispering. Ramesses hesitated, and I saw how keenly he felt Henuttawy’s disappointment in him. She was his father’s sister, after all. He glanced apologetically at me. “I should go and help her,” he said.

“But first, your father wants you in the Audience Chamber.”Henuttawy watched, waiting until Ramesses was inside the palace before she turned to face me. Her slap was so hard that I staggered, spilling Paser’s scrolls across the courtyard floor. “The days when your family ruled in Malkata are over, Princess, and you will never chase Ramesses around this courtyard like an animal! He is the King of Egypt, and you are a child who is tolerated in this palace.”

Henuttawy turned and strode toward the billowing white pavilions. I bent down to pick up Paser’s assignments, and several servants came running.

“My lady, are you all right?” they asked. The entire courtyard had seen what had happened. “Let us help.”

One of the cooks from the kitchen bent down to collect the scattered scrolls.

I shook my head firmly. “It’s fine. I can do it.”

But the cook piled my arms with papyrus. At the entrance to the palace, a woman’s hand took me by the shoulder. I braced myself for more of Henuttawy’s violence, but it was Henuttawy’s younger sister, Woserit.

“Take these scrolls and place them in her room,” Woserit ordered one of the guards. Then she turned to me and said, “Come.”

I followed the hem of her turquoise cloak as it brushed across the varnished tiles and into the ante-chamber where dignitaries waited to see the king. It was empty, but Woserit still swung the heavy wooden doors closed behind us.

“What have you done to anger Henuttawy?”

I still held back tears. “Nothing!”

“Well, she is determined to keep Ramesses away from you.” Woserit watched me for a moment. “Tell me, why do you think Henuttawy is so invested in Iset’s fate?”

I searched Woserit’s face. “I . . . I don’t know.”

“Haven’t you wondered whether Henuttawy has promised to help make Iset a queen in exchange for something?”

I placed two fingers on my lips in a nervous habit I had taken from Merit. “I don’t know. What could Iset have that Henuttawy doesn’t?”

“Nothing, yet. There is no status or bloodline that my sister could offer you. But there is plenty that she can offer Iset. Without Henuttawy’s support, Iset would never have been chosen for a royal wife.”

I wondered why she was telling me this.

“There are a dozen pretty faces Ramesses might have picked,” Woserit continued. “He named Iset because his father suggested her, and my brother recommended her due to Henuttawy’s insistence. But why is my sister so insistent?” she pressed. “What does she hope to gain?”

I sensed that Woserit knew exactly what Henuttawy wanted and I suddenly felt overwhelmed.

“You have never thought of this?” Woserit demanded. “This court is going to bury you, Nefertari, and you will join your family in anonymity if you don’t understand these politics.”

“So what do I do?”

“Decide which path awaits you. Soon, you will no longer be the only young princess in Thebes. And if Iset becomes Chief Wife as Henuttawy wishes, you will never survive here. My sister and Iset will push you from this court and you’ll end your dusty days in the harem of Mi-Wer.”

Even then I knew there was no worse fate for a woman of the palace than to end up in the harem of Mi-Wer, surrounded by the emptiness of the western desert. Many young girls imagine that marrying a Pharaoh will mean a lifetime of ease spent wandering the gardens, gossiping in the baths, and choosing between sandals beaded with lapis or coral—but nothing could be further from the truth. Certainly, there were some women, like Iset’s grandmother, the prettiest or cleverest, who were kept in the harem closest to Pharaoh’s palace. But Malkata’s harem could only house so many women, and most were sent to distant palaces where they were forced to spin and weave to survive. The halls of Mi-Wer were filled with old women, lonely and bitter.

“Only one person can make sure that Iset never becomes Chief Wife with the power to drive you away,” Woserit insisted. “One person close enough to Ramesses to persuade him that Iset should be just another princess. You. By becoming Chief Wife in her place.”

I had been holding my breath, but now, it left me. I sat down on a chair and gripped its wooden arms. “And challenge Iset?” I thought of rising against Henuttawy and suddenly felt sick. “I could never do that. Even if I wanted to, I couldn’t,” I protested. “I’m only thirteen.”