THE MAN WHO SMILED

Henning Mankell has received international acclaim for his Inspector Wallander series, dominating bestseller lists throughout Europe. He devotes much of his time to working with charities to help victims of HIV/Aids in Africa, where he is also the head of the Teatro Avenida in Maputo.

Laurie Thompson is the translator into English of four other books by Henning Mankell, as well as novels by Ake Edwardson, Hakan Nesser and Mikael Niemi.

BY HENNING MANKELL

The Kurt Wallander Mysteries

Faceless Killers

The Dogs of Riga

The White Lioness

The Man Who Smiled

Sidetracked

The Fifth Woman

One Step Behind

Firewall

The Return of the Dancing Master

Before the Frost

I Die, But the Memory Lives On

Chronicler of the Winds

HENNING MANKELL

The Man Who

Smiled

TRANSLATED FROM THE SWEDISH BY

Laurie Thompson

It is not so much the sight of immorality of the great that is to be feared as that of immorality leading to greatness.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Democracy in America

Chapter 1

Fog.

A silent, stealthy beast of prey. Even though I have lived all my life in Skane, where fog is forever closing in and shutting out the world, I'll never get used to it.

9 p.m., October 11, 1993.

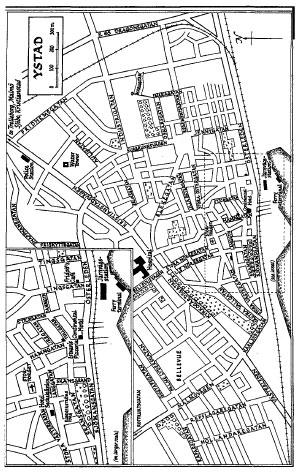

Fog came rolling in from the sea. He was driving home to Ystad and had just passed Brosarp Hills when he found himself in the thick of the white mass.

Fear overcame him straight away.

I'm frightened of fog, he thought. I ought rather to be scared of the man I have just been to see at Farnholm Castle. The friendly man whose menacing staff always lurk in the background, their faces in the shadows. I ought to be thinking about him and what I now know is hidden behind that friendly smile. His impeccable standing in the community, above the very least suspicion. He is the one I ought to be frightened of, not the fog drifting in from Hano Bay. Not now that I have discovered that he would not hesitate to kill anyone who gets in his way.

He turned on the wipers to try to clear the windscreen. He did not like driving in the dark. He particularly disliked it when rabbits scurried this way and that in the headlights.

Once, more than 30 years ago, he had run over a hare. It was on the Tomelilla road, one evening in early spring. He could still remember stamping his foot down on the brake pedal, but then a dull thud against the bodywork. He had stopped and got out. The hare was lying on the road, its back legs kicking. The upper part of its body was paralysed, but its eyes stared at him. He had had to force himself to find a heavy stone from the verge, and had shut his eyes as he threw it down on to the hare's head. He had hurried back to the car without looking again at the animal.

He had never forgotten those eyes and those wildly kicking legs. The memory kept coming back, again and again, usually at the most unexpected times.

He tried now to put the unpleasantness behind him. A hare that died all of 30 years ago can haunt a man, but it can't harm him, he thought. I have more than enough worries about people still in the land of the living.

He noticed that he was checking his rear-view mirror more often than usual.

I'm frightened, he thought again, and I have only just realised that I am running away. I am running from what I know is hidden behind the walls of Farnholm Castle. And they know that I know. But how much? Enough for them to be afraid that I'll break the oath of silence I once took as a newly qualified solicitor? A long time ago that was, when an oath was just that: a sacred commitment to professional secrecy. Are they nervous about their old lawyer's conscience?

Nothing in the rear-view mirror. He was alone in the fog, but in under an hour he would be back in Ystad.

The thought cheered him, if only for a moment. So they weren't following him after all. He had made up his mind what he was going to do tomorrow. He would talk to his son, who was also his colleague and a partner in the legal practice. There was always a solution, that was something life had taught him. There had to be one this time too.

He groped on the unlit dashboard for the radio. The car filled with a man's voice talking about the latest research in genetics. Words passed through his brain without his taking them in. He checked his watch: nearly 9.30. Still no-one behind him, but the fog seemed to be getting even thicker. Nevertheless, he squeezed the accelerator a little harder. The further he was from Farnholm Castle, the calmer he felt. Perhaps, after all, he had nothing to fear.

He forced himself to think clearly.

It had begun with a perfectly ordinary telephone call, a message on his desk asking him to contact a man about a contract that urgently needed verifying. He did not recognise the name, but had taken the initiative and made the call: a small solicitors' practice in an insignificant Swedish town could not afford to reject a potential client. He could recall even now the voice on the phone: polite, with a northern accent, but at the same time giving the impression of a man who measured out his life in terms of what each minute cost. He had explained the task, a complicated transaction involving a shipping line registered in Corsica and a number of cement cargoes to Saudi Arabia, where one of his companies was acting as an agent for Skanska. There had been some vague, passing reference to an enormous mosque that was to be built in Khamis Mushayt. Or maybe it was a university building in Jeddah.

They had met a few days later at the Continental Hotel in Ystad. He had got there early, and the restaurant was not yet open for lunch; he had sat at a table in the corner and watched the man arrive. The only other person there was a Yugoslav waiter staring gloomily out of the window. It was the middle of January, a gale was blowing in from the Baltic and it would soon be snowing. But the man approaching him was suntanned. He wore a dark blue suit and was definitely no more than 50. Somehow, he did not belong either in Ystad or in the January weather. He was a stranger, with a smile that did not belong to that suntanned face.

That was the first time he had set eyes on the man from Farnholm Castle. A man without baggage, in a discrete world of his own, in a blue, tailor-made suit, everything centring on a smile, and an alarming pair of shadowy satellites buzzing attentively but in the background.

Oh yes, the shadows had been there even then. He could not recall either of them being introduced. They sat at a table on the other side of the room, and rose without a word when their master's meeting was over.

Golden days, he thought, bitterly, and I was stupid enough to believe in it. A solicitor's vision of the world should not be influenced by the illusion of a paradise to come, not here on earth at least. Within six months the suntanned man had come to be responsible for half of the practice's turnover, and in a year the firm's income had doubled. Bills were paid promptly, it was never necessary to send a reminder. They had been able to afford to redecorate their offices. The man at Farnholm Castle seemed to be managing his business in every corner of the world, and from places that seemed to be chosen more or less at random. Faxes and telephone calls, even the occasional radio transmission, came from the strangest-sounding towns, some he could only with difficulty find on the globe next to the leather sofa in the reception area. But everything had been above board, albeit complex.

The new age has dawned, he remembered thinking. So this is what it's like. As a solicitor, I have to be grateful that the man at Farnholm picked my name from the telephone book.

His train of recollections was cut short. For a moment he thought he was imagining it, but then he clearly made out the headlights in the rear-view mirror.

They had crept up on him.

Fear struck him immediately. They had followed him after all. They were afraid he would betray his oath of silence.

His first reaction was to accelerate away through the fog. Sweat broke out on his forehead. The headlights were on his tail. Shadows that kill, he thought. I'll never get away, just as none of the others did.

The car passed him. He caught a glimpse of the driver's face, an old man. Then the red rear lights vanished into the fog.

He took out a handkerchief and wiped his face and neck.

I'll soon be home, he thought. Nothing is going to happen. Mrs Duner has recorded in my diary that I was to be at Farnholm today. Nobody, not even he, would send his henchmen to kill off his own elderly lawyer on the way home from a meeting. It would be far too risky.

It was nearly two years before he first realised that something untoward was going on. It was an insignificant assignment, checking contracts that involved the Swedish Trade Council as guarantors for a considerable sum of money. Spare parts for turbines in Poland, combine harvesters for Czechoslovakia. It was a minor detail, some figures that didn't add up. He thought it was probably a misprint, maybe somewhere two digits had been muddled. He had gone through it all again and realised that it was no accident, it was all intentional. Nothing was missing, everything was correct, but the upshot was horrifying. His first instinct had been not to believe it. He had leaned back in his chair - it was late in the evening, he recalled - taking in that there was no doubt that he had uncovered a crime. It was dawn before he had set out to walk the streets of Ystad, and by the time he reached Stortorget he had reluctantly accepted that there was no alternative explanation: the man at Farnholm Castle was guilty of a gross breach of trust regarding the Trade Council, of tax evasion and of a whole string of forgeries.

There after he had been constantly on the lookout for the black holes in every document emanating from Farnholm. And he found them - not every time, but more often than not. The extent of the criminality had slowly dawned on him. He tried not to acknowledge the evidence he could not avoid registering, but in the end he had to face up to the facts. But on the other hand he had done nothing about it. He had not even told his son. Was this because, deep down, he preferred to believe it wasn't true? Nobody else, apparently not even the tax authorities, had noticed anything. Perhaps he had uncovered a secret that was purely hypothetical? Or was it that it was all too late anyway, now that the man from Farnholm Castle was the principal source of income for the firm?

The fog was more or less impenetrable now. He hoped it might lift as he got nearer to Ystad.

He couldn't go on like this, that was certain. Not now that he knew that the man had blood on his hands.

He would talk to his son. The rule of law still applied in Sweden, for heaven's sake, even though it seemed to be undermined and diluted day by day. His own complaisance had been a part of that process. His having for so long turned a blind eye was no reason now for remaining silent.

He would never bring himself to commit suicide.

Suddenly he saw something in the headlights. He slammed on the brakes. At first he thought it was a hare. Then he realised there was something in the road.

He turned his headlights on full beam.

It was a chair, in the middle of the road. A simple kitchen chair. Sitting on it was a human-sized effigy. Its face was white.

Or could it be a real person made up like a tailor's dummy?

He felt his heart starting to pound. Fog swirled in the light of his headlamps. There was no way he could shut out the chair and the effigy. Nor could he ignore his mounting fear. He checked his rear-view mirror. Nothing. He drove slowly forward until the chair and the effigy were no more than ten metres from the car. Then he stopped again.

The dummy looked impressively like a human being. Not just some kind of hastily got-up scarecrow. It's for me, he thought. He switched off the radio, his hand trembling, and pricked up his ears. Fog, and silence. He didn't know what to do next.

What made him hesitate was not the chair out there in the fog, nor the ghostly effigy. There was something else, something in the background, something he couldn't make out. Something that probably existed only inside himself.

I'm very frightened, he said to himself, and fear is undermining my ability to think straight.

Finally, he undid his safety belt and opened the door. He was surprised by how cool it felt outside. He got out, his eyes fixed on the chair and the dummy lit up by the car's headlights. His last thought was that it reminded him of a stage set with an actor about to make his entrance.

He heard a noise behind him, but he didn't turn. The blow caught him on the back of his head.

He was dead before his body hit the damp asphalt.

It was 9.53 p.m. The fog was now very dense.

Chapter 2

The wind was gusting from due north.

The man, a long way out on the freezing cold beach, was suffering in the icy blasts. He kept stopping and turning his back to the wind. He would stand there, motionless, staring at the sand, his hands deep in his pockets; then he would go on walking, apparently aimlessly, until he would be lost from sight in the grey twilight.

A woman who every day walked her dog on the sands had grown anxious about the man who seemed to patrol the beach from dawn to dusk. He had turned up out of the blue a few weeks ago, a species of human jetsam washed ashore. People she came across on the beach normally greeted her. It was late autumn, the end of October, so in fact she seldom came across anybody at all. But the man in the black overcoat never acknowledged her. At first she thought he was shy, then rude, or perhaps a foreigner. Gradually she came to feel that he was weighed down by some appalling sorrow, that his beach walks were a pilgrimage taking him away from some unknowable source of pain. His gait was decidedly erratic. He would walk slowly, almost dawdling, then suddenly come to life and break into what was almost a trot. It seemed to her that what dictated his movements was not so much physical as his disturbed spirit. She was convinced that his hands were clenched into fists inside his pockets.

After a week she thought she had worked it out. This stranger had landed on this strand from somewhere or other in order to come to terms with a serious personal crisis, like a vessel with inadequate charts edging its way through a treacherous channel. That must be the cause of his introversion, his restless walking. She had mentioned the solitary wanderer on the beach every night to her husband, whose rheumatism had forced him into early retirement. Once he had even accompanied her and the dog though his condition caused him a great deal of pain and he was much happier staying indoors. He had thought that his wife was right, though he'd found the man's behaviour so strikingly out of the ordinary that he had phoned a friend in the Skagen police and confided in him his own and his wife's observations. Possibly the man was on the run, wanted for some crime, or had absconded from one of the few mental hospitals left in the country? But the police officer had seen so many odd characters over the years, most of them having made the pilgrimage to the furthest tip of Jutland only in search of peace and quiet, that he counselled his friend to be wise: just leave the man alone. The strand between the dunes and the two seas that met there was a constantly changing no man's land for whoever needed it.

The woman with her dog and the man in the black overcoat went on passing each other like ships in the night for another week. Then one day - on October 20, 1993, in point of fact - something happened which she would later connect with the man's disappearance.

It was one of those rare days when there was not a breath of wind, when the fog lay motionless over both land and sea. Foghorns had been sounding in the distance like lost, invisible cattle. The whole of this strange setting was holding its breath. Then she had caught sight of the man in the black overcoat and stopped dead.

He was not alone. He was with a shortish man in a light-coloured windcheater and cap. She noticed that it was the new arrival who was doing the talking, and seemed to be trying to convince the other about something. Occasionally he took his hands from his pockets and gestured to underline what he was saying. She could not hear what they were saying, but there was about the smaller man's manner something that told her he was upset.

After a while they set off along the beach and were swallowed up by the fog.

The following day the man was alone again. Five days later he was gone. She walked the dog on the beach every morning until well into November, expecting to come across the man in black; but he did not reappear. She never saw him again.

For more than a year Kurt Wallander, a detective chief inspector with the Ystad police, had been on sick leave, unable to carry out his duties. During that time a sense of powerlessness had come to dominate his life and affected his actions. Time and time again, when he could not bear to stay in Ystad and had some money to spare, he had gone off on pointless journeys in the vain hope of feeling better, perhaps even of recovering his zest for life, if only he were somewhere other than Skane. He had taken a package holiday to the Caribbean, but had drunk himself silly on the outward flight and had not been entirely sober for any of the fortnight he spent in Barbados. His general state of mind was one of increasing panic, a sense of being totally alienated. He had skulked in the shade of palm trees, and some days had not even set foot outside his hotel room, unable to overcome a primitive need to avoid the company of others. He had bathed just once, and then only when he'd stumbled on a jetty and fallen into the sea.

Late one evening when he had forced himself to go out and mix with other people, but also in order to replenish his stock of alcohol, he had been solicited by a prostitute. He wanted to wave her away and yet somehow encouraged her at the same time, and was only later overwhelmed by misery and self-disgust. For three days, of which he afterwards had no clear memory, he spent all his time with the girl in a shack stinking of vitriol, in a bed with sheets smelling of mould and cockroaches crawling over his sweaty face. He could not even remember the girl's name or if he had ever discovered what it was. He had taken her in what could only have been a fit of unbridled lust. When she had extracted the last of his money two burly brothers appeared and threw him out. He went back to the hotel and survived by forcing down as much as he could of the breakfast included in the price, eventually arriving back at Sturup airport in a worse state than when he had left.

His doctor, who gave him regular check-ups, forbade him any more such trips as there was a real danger that Wallander would drink himself to death. But two months later, at the beginning of December, he was off again, having borrowed money from his father on the pretext of buying some new furniture in order to raise his spirits. Ever since his troubles started he had avoided his father, who had just married a woman 30 years his junior who used to be his home help. The moment he had the money in his hand, he made a beeline for the Ystad Travel Agency and bought a three-week package holiday in Thailand. The pattern of the Caribbean repeated itself, the difference being that catastrophe was narrowly averted because a retired pharmacist who had sat next to him on the flight and who happened to be at the same hotel took pity on him and stepped in when Wallander began drinking at breakfast and generally acting strangely. The pharmacist's intervention resulted in Wallander's being sent home a week earlier than planned. On this holiday, too, he had surrendered to his self-disgust and thrown himself into the arms of prostitutes, each one younger than the last. There followed a nightmarish winter when he was in constant dread of having contracted the fatal disease.

By the end of April, when he had been off work for ten months, it was confirmed that he was not in fact infected; but he seemed not to react to the good news. That was about the time his doctor began to wonder if Wallander's days as a police officer were over, whether indeed he would ever be fit to work again, or was ready for immediate early retirement on the grounds of ill health.

That was when he went - perhaps "ran away" would be more accurate - to Skagen the first time. By then he had managed to stop drinking, thanks not least to his daughter Linda coming back from Italy and discovering the mess both he and his flat were in. She had reacted in exactly the right way: emptied all the bottles scattered about the flat, and read him the riot act. For the two weeks she stayed with him in Mariagatan, he at last had somebody to talk to. Together they were able to lance most of the abscesses eating into his soul, and by the time she left she felt that she might be able to give a little credence to his promise to stay off the booze. On his own again and unable to face the prospect of sitting around in the empty flat, he had seen an advertisement in the newspaper for an inexpensive guest house in Skagen.

Many years before, soon after Linda was born, he had spent a few weeks in the summer at Skagen with his wife Mona. They had been among the happiest weeks of his life. They were short of money and lived in a tent that leaked, but it seemed to them that the whole universe was theirs. He telephoned that very day and booked himself a room starting in the first week of May.

The landlady was a widow, Polish originally, and she left him to his own devices. She lent him a bicycle. Every morning he went riding along the endless sands. He took a plastic carrier bag with a packed lunch, and did not come back to his room until late in the evening. His fellow guests were elderly, singles and couples, and it was as quiet as a library reading room. For the first time in over a year he was sleeping soundly, and he had the feeling his insides were shedding the effects of his heavy drinking.

During that first stay at the guest house in Skagen he wrote three letters. The first was to his sister Kristina. She had often been in contact during the past year, asking how he was. He had been touched by her concern, but he had scarcely been able to bring himself to write to her, or to telephone. Things were made worse by a vague memory of having sent her a garbled postcard from the Caribbean when he was far from sober. She had never mentioned it, he had never asked; he hoped he had been so drunk that he had got the address wrong, or forgotten to put a stamp on the card. Now he sat in bed one night and wrote to her, resting the paper on his briefcase. He tried to describe the feeling of emptiness, of shame and guilt that had dogged him ever since he had killed a man last year. He had unquestionably acted in self-defence, and not even the most aggressive and police-hating of reporters had taken him to task, but he felt that he would never manage to shake off the burden of guilt. His only hope was that he might one day learn to live with it.

"I feel as if part of my soul has been replaced by an artificial limb," he wrote. "It still doesn't do what I want it to do. Sometimes, in my darkest moments, I'm afraid it might never again obey me, but I haven't given up hope altogether."

The second letter was to his colleagues at the police station in Ystad, and by the time he was about to put it in the red letter box outside the post office in Skagen, he realised that a good part of what he had written was untrue, but that he had to send it even so. He thanked them for the hi-fi system they had clubbed together to give him last summer, and asked them to forgive his not having done so earlier. He meant all that sincerely, of course. But when he ended the letter by saying he was getting better and hoped to be back at work soon, those were just meaningless words: the polar opposite was nearer the truth.

The third letter he wrote during that stay in Skagen was to Baiba Liepa. He had written to her every other month or so over the past year, and she had replied every time. He had begun to think of her as his private patron saint, and his fear of upsetting her so that she might stop replying led him to suppress his feelings for her. Or at least he thought he had. The long, drawn-out process of being undermined by inertia had made him unsure of anything any more. He had brief interludes of absolute clarity, usually when he was on the beach or sitting among the dunes sheltering from the biting cold winds blowing off the sea, and it sometimes seemed to him the whole thing was pointless. He had met Baiba for only a few days in Riga. She had been in love with her murdered husband, Karlis, a captain in the Latvian police force - why in God's name should she suddenly transfer her affections to a Swedish police officer who had done no more than was demanded of him by his profession, even if it had happened in a somewhat unorthodox fashion? But he had no great difficulty dismissing those moments of insight. It was as if he did not dare risk losing what deep down he knew was something he did not even have. Baiba, his dream of Baiba, was his last line of defence. He would defend it to the bitter end, even if it was only an illusion.

He stayed ten days at the guest house, and when he went back to Ystad he had already made up his mind to return as soon as he could. By mid July he was in his old room again. Again the widow lent him a bicycle and he spent his days by the sea. Unlike the first time, the beach was now full of holidaymakers, and he felt as if he was wandering like an invisible shadow among all these people as they laughed, played and paddled. It was as if he had established a territory on the beach where the two seas met, an area under his personal control invisible to everyone else, where he could patrol and keep an eye on himself as he tried to find a way out of his misery. His doctor thought he could detect some improvement in Wallander after his first spell in Skagen, but the indications were still too weak for him to assert that there had been a definite change for the better. Wallander asked if he could stop taking the medication he had been on for more than a year, since it made him feel tired and sluggish, but the doctor urged him to be patient for a little longer.

Every morning he wondered if he would have the strength to get out of bed, but it was easier when he was at the guest house in Skagen. There were moments when he felt he could forget the awful events of the previous year, and there were glimmerings of hope that he might after all have a future.

As he wandered the beach for hour after hour, he began slowly to go through what lay behind it all, searching for a way to overcome and cast off the burden, maybe even to find the strength to become a police officer again, a police officer and a human being.

It was during that visit that he had stopped listening to opera. He would often take his little cassette player on his walks along the beach, but one day it came to him that he had had enough. When he got back to the guest house that evening he packed all his opera cassettes away into his suitcase and put it in the wardrobe. The next day he cycled into Skagen and bought some recordings of pop artists he had barely heard of. What surprised him most was that he did not miss the music that had kept him going for so many years.

I have no space left, he thought. Something inside me has filled up to the brim, and soon the walls will burst.

*

He was back in Skagen in the middle of October. He was firmly resolved this time to work out what he would do with the rest of his life. His doctor had encouraged him to return to the guest house, which obviously did his patient good. There were signs of a gradual return to health, a tentative withdrawal from the depths of depression. Without betraying his oath of confidentiality, he also intimated to Bjork, Wallander's boss, that there might just possibly be a chance of the invalid coming back to work at some point.

So Wallander went to Denmark again and set out once more on his walks along the beach. It was late autumn and the sands were deserted. He seldom encountered another human being, and the ones he did see were mostly old, apart from the occasional sweat-stained jogger; and there was a busybody regularly walking her dog. He resumed his patrols, watching over his lonely territory, marching with gathering confidence towards the just visible and constantly shifting line where the beach met the sea.

He was well into middle age now, and the milestone of 50 was not far off. During the last year he had lost so much weight he found himself having to hunt in his wardrobe for clothes he had been unable to get into for the past seven or eight years. He was in better physical shape than he had enjoyed for ages, especially now that he had stopped drinking. That seemed to him a possible starting point for his future plans. Barring accidents, he could have at least 20 more years to live. What exercised him most was whether he would be able to return to police duties, or whether he would have to find something else to do. He refused even to consider early retirement on health grounds. That was a prospect he didn't think he could cope with. He spent his time on the beach, usually enveloped in drifting fog but with occasional days of fresh, clear air, glittering seas and gulls soaring up above. Sometimes he felt like the clockwork man who had lost the key that normally stuck out of his back, and hence lacked the possibility of being wound up, of finding new sources of energy. He pondered his options were he forced to leave the police force. He might become a security guard or the like with some firm or other. He could not see what his service as a police officer actually qualified him for, apart from chasing criminals. His options were limited, unless he decided to make a clean break and put behind him his many years of police work. But who would be willing to employ a former officer approaching 50, whose only expertise was unravelling more or less confused crime scenes?

When he felt hungry he would leave the beach and find a sheltered spot in the dunes. He tucked into his packed lunch and used the plastic carrier bag to sit on, protecting himself from the cold sand. As he ate, he tried hard - without much success - to think of something other than his future. He made every effort to be realistic, but always he had to fend off unrealistic dreams.

Like all other police officers, he was sometimes tempted to go over to the other side. He never ceased to be amazed by the officers who had turned criminals and yet failed to use their knowledge of fundamental police procedures that would have helped them to avoid being caught. He often toyed with schemes which would instantly make him rich and independent, but usually it did not take long to come to his senses and banish any such thoughts with a shudder. What he wanted least of all was to follow in the steps of his colleague Hanson, who seemed to him obsessed, spending so much of his time betting on horses that hardly ever won. Wallander could not imagine himself ever wasting time like that.

He kept coming back to the question of whether he was duty-bound to return to the police force. Start work again, fight off the memories of what happened a year ago, and maybe one day manage to live with them. The only realistic option was for him to go on as before. That was the nearest he came to finding a glimmer of a meaning in life: helping people to lead as secure an existence as possible, removing the worst criminals from the streets. To give up on that would not only mean turning his back on a job he knew he did well - perhaps better than most of his colleagues - it would also mean undermining something deep inside him, the feeling of being a part of something greater than himself, something that made his life worth living.

But eventually, when he had been in Skagen a week, and autumn was showing signs of turning into winter, he was forced to admit that he would not now be up to the job. His career as a police officer was over, the wounds inflicted by what happened the previous year had changed him irrevocably. It was an afternoon when the beach was shrouded in thick fog when he decided that the arguments for and against were exhausted. He would talk to his doctor and to Bjork. He would not return to duty.

Deep down he felt a vague sense of relief. Now at least he knew the score. The man he had killed last year in the field with all the sheep hidden in the fog had his revenge.

He cycled in to Skagen that night and got drunk in a little, smoke-filled bar, where the customers were few and far between and the music too loud. He knew that for once he would not be carrying on his binge the next day. This was merely a way of confirming the fateful conclusion he had reached, that his life as a policeman had come to an end. Riding back to the guest house at the dead of night, he fell off and grazed his cheek. The landlady had noticed his absence and was sitting up, waiting for him. Despite his protests, she insisted on cleaning the blood off his face and on taking his filthy clothes to wash. Then she helped him to unlock the door of his room.

"There was a man here this evening, asking for Mr Wallander," she said, handing him back the key.

He looked blankly at her.

"Nobody asks for me," he said. "Nobody even knows I'm here."

"This man did," she said. "He was anxious to find you."

"Did he give you his name?"

"No, but he was Swedish."

Wallander shook his head and tried to put it out of his mind. He did not want to see anybody, and nobody wanted to see him either, he was sure of that.

The next day he was full of regrets and went back to the beach, never giving a thought to what the landlady had told him. The fog was thick, and he felt very tired. For the first time he asked himself what he thought he was doing on the beach. After only a kilometre or so he wondered if he had the strength to go on, and sat down on the upturned hulk of a large rowing boat half-buried in the sand.

It was then that he noticed a man approaching through the fog. It was as if somebody had intruded on the privacy of his office out there on the boundless sands.

His first impression was of a blurred stranger, wearing a windcheater and a cap that seemed too small for his head. Then he seemed vaguely familiar, but it was not until he had come closer and Wallander had stood up that he realised who it was. They shook hands, and Wallander wondered how on earth his refuge had been discovered. He tried to remember when he had last seen Sten Torstensson, and thought that it must have been in connection with some court proceedings that last fateful spring.

"I came to see you last night at the guest house," Torstensson said. "I don't want to disturb you, of course, but I must talk to you."

Once upon a time I was a police officer and he was a solicitor, Wallander thought, that's all there was to it. We used to sit on either side of criminals, and occasionally but not very often we might argue about whether or not an arrest was justified. We got to know each other a bit better during the difficult period of my divorce from Mona, when he took care of my interests. One day we realised something had clicked, something that might be the beginnings of a friendship. Friendship often develops out of a meeting at which nobody had expected any such miracle to happen. But friendship is a miracle, that's something life has taught me. He invited me out sailing one weekend. It was blowing a gale, and I vowed I would never set foot on a sailing boat again. Then we started meeting, not all that often, not regularly. And now he's tracked me down and wants to talk.

"I heard that somebody had been asking for me," Wallander said. "How the hell did you find me here?"

He knew he was making it clear he resented being disturbed in his refuge among the dunes.

"You know me," Torstensson said, "I'm not the sort to make a nuisance of myself. My secretary claims I'm sometimes frightened of being a nuisance to myself, whatever she means by that. But I phoned your sister in Stockholm. Or rather, I got in touch with your father and he gave me her number. She knew the name of the guest house, and where it was. And so here I am. I stayed the night at the hotel next to the Art Museum."

They had started walking along the beach, the wind behind them. The woman who was always out with her dog had stopped and was staring at them, and Wallander was sure she would be surprised to see he had a visitor. They walked in silence, and Wallander waited for Torstensson to speak, feeling how odd it was to have someone by his side.

"I need your help," Torstensson said, eventually. "As a friend and as a police officer."

"As a friend," Wallander said. "If I can. Which I doubt. But not as a police officer."

"I know you're still off work," Torstensson said.

"Not only that. You can be the first to know that I'm packing it in altogether."

Torstensson stopped in his tracks.

"That's how it is," Wallander said. "But tell me why you're here."

"My father's dead."

Wallander had known him. He, too, was a solicitor, although he only occasionally appeared in court. As far as Wallander could remember, the older Torstensson spent most of his time advising on financial matters. He tried to work out how old he must have been. Getting on for 70, he supposed, an age by which quite a lot of people are dead already.

"He died in a road accident some weeks ago," Torstensson said. "Just south of Brosarp Hills."

"I'm sorry to hear that," Wallander said. "What happened?"

"That's a good question. That's why I'm here."

Wallander looked at him blankly.

"It's cold," Torstensson said. "They serve coffee at the Art Museum. I have the car with me."

Wallander nodded. His bicycle was sticking out of the boot as they drove through the dunes. There were not many customers in the Art Museum cafe at that time in the morning. The girl behind the counter was humming a tune Wallander was surprised to recognise from one of his new cassettes.

"It was late in the evening," Torstensson began. "October 11, to be precise. Dad had been to see one of our most important clients. According to the police he'd been driving too fast, lost control, the car had overturned and he was killed."

"It can happen in a flash," Wallander said. "Lose concentration for just a second, and the result can be catastrophic."

"It was foggy that evening," Torstensson said. "Dad never drove fast. Why would he have done so when it was foggy? He was obsessed by the fear of running over a hare."

Wallander studied him. "What's on your mind?"

"Martinsson was in charge of the case."

"He's good," Wallander said. "If Martinsson says that's what happened, there's no reason to think otherwise."

Torstensson looked gravely at him. "I've no doubt Martinsson is a good police officer," he said. "Nor do I doubt they found my father dead in his car, which was upside down and badly knocked about in a field beside the road. But there's too much that doesn't add up. Something more must have happened."

"What?"

"Something else."

"Such as?"

"I don't know."

Wallander went to the counter to refill his cup.

Why don't I tell him the truth? he wondered. That Martinsson is both imaginative and energetic, but can on occasions be careless.

"I've read the police report," Torstensson said, when Wallander had sat down again. "I've taken it with me and read it at the spot where my father died. I've read the post-mortem notes, I've spoken to Martinsson, I've done some thinking and I've asked again. Now I'm here."

"What can I do?" Wallander said. "You're a solicitor, you know that in every case there are a few loose ends that we can never manage to tie up. I take it your father was alone in the car when it happened. If I understand you rightly, there were no witnesses. Which means the only person who could tell us exactly what happened was your father."

"Something happened," Torstensson said. "Something's not right and I want to know what it is."

"I can't help you, although I'd like to."

Torstensson seemed not to hear him. "The keys," he said. "Just to give you one example. They weren't in the ignition. They were on the floor."

"They could have been knocked out," Wallander said. "When a car crashes, anything can happen."

"The ignition was undamaged," Torstensson said. "The ignition key was not even bent."

"There could be an explanation even so."

"I could give you other examples," Torstensson insisted. "I know that something happened. My dad died in a car accident that was really something else."

Wallander thought before replying. "Might he have committed suicide?"

"That possibility did occur to me, but I'm sure it can be discounted. I knew my father well."

"The majority of suicides are unexpected," Wallander said. "But, of course, you know best what you want to believe."

"There's another reason why I cannot accept the accident theory," Torstensson said.

Wallander looked at him sharply.

"My father was a cheerful, outgoing man," Torstensson said. "If I hadn't known him so well, I might not have noticed the change. Little things, barely noticeable, but very definitely a change in his mood during the last six months."

"Can you be more precise?"

Torstensson shook his head. "Not really," he said. "It was just a feeling I had. Something was worrying him. Something he was very keen to make sure I wouldn't notice."

"Did you ever speak to him about it?"

"Never."

Wallander put his empty cup down. "I'd like to help you, but I can't," he said. "As your friend, I can listen to what you have to say. But I no longer exist as a police officer. I don't even feel flattered by the fact that you've come all the way here to talk to me. I just feel numb and tired and depressed."

Torstensson opened his mouth to speak, but thought better of it.

They stood up and left the cafe.

"I respect what you say, of course," Torstensson said as they stood outside the Art Museum.

Wallander went with him to the car and recovered his bicycle.

"We never know how to handle death," Wallander said in a clumsy attempt to convey his sympathy.

"I'm not asking you to," Torstensson said. "I just want to know what happened. That was no ordinary car accident."

"Have another word with Martinsson," Wallander said. "But it might be best if you don't mention that I suggested that."

They said goodbye, and Wallander watched the car drive off through the dunes.

He was struck by the feeling that matters were getting urgent. He couldn't keep dragging things out any longer. That afternoon he telephoned his doctor and Bjork and informed them that he had decided to resign from the police force.

He stayed at Skagen for five more days. The feeling that his soul was a devastated bomb site was as strong as ever. But he felt relieved nevertheless, having had the strength to make up his mind despite everything.

He came back to Ystad on Sunday, October 31, in order to sign the various forms that would draw the line under his police career.

On the Monday morning, November 1, he lay in bed with his eyes wide open after the alarm went off at 6.00. Apart from brief periods of restless dozing, he had been awake all night. Several times he had got out of bed and stood at the window overlooking Mariagatan, thinking that he had made yet another wrong decision. Perhaps there was no obvious path for him to follow for the rest of his life. Without finding any satisfactory answer to that, he had sat on the sofa in the living room listening to the radio. Eventually, just before the alarm rang, he had accepted that he had no choice. He was running away, no doubt about that; but everybody runs away sooner or later, he told himself. Invisible forces get the better of all of us in the end. Nobody escapes.

He got up, dressed, went out for the morning paper, came home, put on the water for coffee and took a shower. It felt odd, going back to the old routine just for a day. As he dried himself down, he tried to recall his last working day almost 18 months ago. It was summer when he cleared his desk and then went to the harbour cafe to write a gloomy letter to Baiba. He found it hard to decide whether it felt like an age ago, or just yesterday.

He sat at the kitchen table and stirred his coffee.

Then it had been his last day at work for who knew how long. Now it was his last day at work, ever.

He had been in the police force for more than 25 years. No matter what happened in the years to come, those years would be the backbone of his life, nothing could change that. Nobody can ask to have their life declared invalid, and demand that the dice be thrown afresh. There is no going back. The question was whether there was any way forward.

He tried to identify his emotions this cold morning, but all he felt was emptiness. It was as if the autumn mists had penetrated his consciousness.

He gave a sigh, and turned to his newspaper. He leafed through it and had the distinct impression that he had seen all the photographs and read all the articles any number of times before.

He was about to put it down when a death announcement caught his eye. Sten Torstensson, solicitor, born March 3, 1947, died October 26, 1993.

He stared hard at the notice. Surely it was the father, Gustaf Torstensson, who was dead? He had talked to Sten just over a week ago, on the sands at Skagen.

He tried to work out what it meant. It must be somebody else. Or the names had got mixed up. He read it again. There was no mistake. Sten Torstensson, the man who'd come to see him in Denmark five days ago, was dead.

He sat there, motionless.

Then he stood up, checked in the phone book and dialled a number. The person he was calling was an early riser.

"Martinsson."

Wallander resisted an urge to put the receiver down. "It's me, Kurt," he said. "I hope I didn't wake you up."

There was a long silence before Martinsson responded. "Is it really you?" he said. "Now there's a surprise!"

"I can imagine," Wallander said. "But there is something I need to ask you."

"It can't be true that you're packing it in."

"That's the way it goes," Wallander said. "But that's not why I'm calling. I want to know what happened to Sten Torstensson, the lawyer."

"Haven't you heard?"

"I only got back to Ystad yesterday. I haven't heard anything."

There was a pause. "He was murdered," Martinsson said at last.

Wallander was not surprised. The moment he had seen the notice in the paper, he had known it was not death by natural causes.

"He was shot in his office last Tuesday night," Martinsson said. "It's beyond belief. And tragic. It's only a few weeks since his father was killed in a car accident. But maybe you didn't know that either?"

"No," Wallander lied.

"You've got to come back to work," Martinsson said. "We need you to sort this out. And much more besides."

"No. My mind's made up. I'll explain when we meet. Ystad's a little town. You bump into everybody sooner or later."

Then Wallander said goodbye and hung up.

As he did so, he realised that what he had just said to Martinsson was no longer true. In just a few seconds, everything had changed.

He stood by the phone for more than five minutes. Then he drank his coffee, dressed and went down to his car. At 7.30 he walked through the police-station door for the first time in 18 months. He nodded to the security guard in reception, made a beeline for Bjork's office and knocked on the door. Bjork stood up as he came in, and Wallander noticed that he was thinner. He could see, too, that Bjork was uncertain as to how to deal with the situation.

I'm going to make it easy for him, Wallander thought. He won't understand a thing at first, but then, neither do I.

"Naturally we're pleased to hear you seem to be better," Bjork began, hesitantly. "But, of course, we'd prefer you to be coming back to work rather than leaving us. We need you." He gestured towards his desk, piled high with papers. "Today I have to respond to important matters such as a proposed new design for police uniforms, and yet another incomprehensible draft for a change in the system involving relations between the county constabulary and the county police chiefs. Have you kept up with this?"

Wallander shook his head.

"I wonder where we're heading?" said Bjork, glumly. "If the new uniform design goes through, it's my belief that in future police officers will look like something between a carpenter and a ticket collector."

He looked at Wallander, inviting a comment, but Wallander said nothing.

"The police were nationalised in the 1960s," Bjork said. "Now they're going to do it all over again. Parliament wants to abolish local constabularies and create something entirely new and call it the National Police Force. But the police has always been a national force. What else could it be? The sovereign legal systems of independent provinces were lost in the Middle Ages. How do they think anybody can get on with a day's work when they're buried under an avalanche of woolly memoranda? To cap it all I have to prepare a lecture for a totally unnecessary conference on what they call 'refusal-of-entry techniques'. What they mean is what to do when aliens who can't get a visa have to be loaded on to buses and ferries and deported without too much kerfuffle and protest."

"I realise you're very busy," Wallander said, thinking that Bjork hadn't changed an atom. He'd never got his role as Chief of Police under control. The job controlled him.

"I've got all the papers here," Bjork went on. "All we need is your signature, and you're an ex-policeman. I have to accept your decision, even if I don't like it. By the way, I hope you don't mind, but I've called a press conference for 9 a.m. You've become a famous police officer in the last few years, Kurt. Even if you've acted a little strangely every now and again, there's no denying you've done a lot for our good name and reputation. They do say that there are police cadets who claim to have been inspired by you."

"I'm sure that's not true," Wallander said. "And you can cancel the press conference."

He could see that this annoyed Bjork.

"Out of the question," he said. "It's the least you can do for your colleagues. Besides, Swedish Police magazine is going to run a feature on you."

Wallander walked up to Bjork's desk.

"I'm not packing it in," he said. "I've come here today to start work again."

Bjork stared at him in astonishment.

"There won't be a press conference," Wallander said. "I'm starting work again as of now. I'm going to get the doctor to sign a certificate to say I'm fit. I feel good. I want to work."

"I hope you're not pulling my leg," said Bjork, uneasily.

"No," Wallander said. "Something's happened that's changed my mind."

"This is very sudden."

"For me as well. To be precise it's just over an hour since I changed my mind. But I have one condition. Or rather, a request."

Bjork waited.

"I want to be in charge of the Sten Torstensson case," Wallander said. "Who's in charge at the moment?"

"Everybody's involved," Bjork said. "Svedberg and Martinsson are in the main team, together with me. Akeson is the prosecutor in charge."

"Young Torstensson was a friend of mine," Wallander said.

Bjork nodded and rose to his feet. "Is this really true?" he said. "Have you really changed your mind?"

"You heard what I said."

Bjork walked round his desk and stood face to face with Wallander. "That's the best piece of news I've heard for a very long time," he said. "Let's tear these documents up. Your colleagues are in for a surprise."

"Who's got my old office?" Wallander said.

"Hanson."

"I'd like it back, if possible."

"Of course. Hanson's on a course in Halmstad this week anyway. You can move in straight away."

They walked down the corridor together until they came to Wallander's old office. His nameplate had been removed. That threw him for a moment.

"I need an hour to myself," Wallander said.

"We have a meeting at 8.30 about the Torstensson murder," Bjork said. "In the little conference room. You're sure you're serious about this?"

"Why shouldn't I be?"

Bjork hesitated before continuing. "You have been known to be a bit whimsical, even injudicious," he said. "There's no getting away from that."

"Don't forget to cancel the press conference," Wallander said.

Bjork reached out his hand. "Welcome back," he said.

"Thanks."

Wallander closed the door behind Bjork and immediately took the phone off the hook. He looked round the room. The desk was new. Hanson had brought his own. But the chair was Wallander's old one.

He hung up his jacket and sat down.

Same old smell, he thought. Same furniture polish, same dry air, same faint aroma of the endless cups of coffee that get drunk in this station.

He sat for a long time without moving.

He'd agonised for a year and more, searched for the truth about himself and his future. A decision had gradually formed and broken through the indecision. Then he had started reading a newspaper and everything had changed.

For the first time in ages he felt a glow of satisfaction.

He had reached a decision. Whether it was the right one he could not say. But that didn't matter any more.

He reached for a notepad and wrote: Sten Torstensson. He was back on duty.

Chapter 3

At 8.30, when Bjork closed the door of the conference room, Wallander felt as if he had never been away. The year and a half that had passed since his last investigation meeting had been erased. It was like waking up from a long slumber during which time had ceased to exist.

They were sitting around the oval table, as so often before. As Bjork had still not said anything, Wallander assumed his colleagues were expecting a short speech to thank them for their friendship and cooperation over the years. Then he would take his leave and the rest would concentrate on their notes and get on with the search for the killer of Sten Torstensson.

Wallander realised that he had instinctively taken his usual place, on Bjork's left. The chair on the other side was empty. It was as if his colleagues did not want to intrude too closely on somebody who did not really belong any more. Martinsson sat opposite him, sniffing loudly. Wallander wondered when he had ever seen Martinsson without a cold. Next to him sat Svedberg, rocking backwards and forwards on his chair and scratching his bald head with a pencil, as usual.

Everything would have been just as before, it seemed to Wallander, had it not been for the woman in jeans and a blue blouse sitting on her own at the opposite end of the table. He had never met her, but he knew who she was, and even knew her name. It was almost two years since they had started talking about strengthening the Ystad force, and that was when the name Ann-Britt Hoglund had cropped up for the first time. She was young, had graduated from Police Training College barely three years before, but had already made a name for herself. She had received one of two prizes awarded on the basis of final examinations and general achievements in the assessment of her fellow cadets. She came from Svarte originally, but had grown up in the Stockholm area. Police forces all over the country had tried to enrol her, but she made it clear she would like to return to Skane, the province of her birth, and took a job with the Ystad force.

Wallander caught her eye, and she smiled fleetingly at him.

So, it is not the same as it was before, he thought. With a woman among us, nothing can stay as it used to be.

That was as much as he had time to think. Bjork had risen to his feet, and Wallander sensed that he was nervous. Perhaps it had been too late. Perhaps his contract had already been terminated without his knowing?

"Monday mornings are normally hard going," Bjork said. "Especially when we have to deal with the particularly unpleasant and incomprehensible murder of one of our colleagues, Mr Torstensson. But today I am able to commence our meeting with some good news. Kurt has announced that he is back to good health, and is starting work again as of now. I am the first to welcome him back, of course, but I know all my colleagues feel the same. Including Ann-Britt Hoglund, whom you haven't met yet."

There was silence. Martinsson stared at Bjork in disbelief, and Svedberg put his head to one side, gaping at Wallander as if he couldn't believe his ears. Ann-Britt Hoglund looked as if what Bjork had just said hadn't sunk in.

Wallander felt bound to say something. "It's true," he said. "I'm starting work again today."

Svedberg stopped rocking to and fro and slammed the palms of his hands down on the table with a thud. "That's terrific news, Kurt. We couldn't have managed another damned day without you."

Svedberg's spontaneous comment made the whole room burst out laughing. One after another they stood up in a queue to shake Wallander by the hand. Bjork tried to organise coffee and pastries, and Wallander had difficulty in hiding the fact that he was moved.

It was all over in a few minutes. There was no more time for emotional outpourings for which Wallander was grateful, at least for now. He opened the notebook he had brought with him from his office, containing nothing but Sten Torstensson's name.

"Kurt has asked me if he can join the murder investigation without more ado," Bjork said. "Of course he can. I think the best way to kick off is by making a summary of how things stand. Then we can give Kurt a little time to familiarise himself with the particulars."

He nodded to Martinsson, who had obviously been the one to take on Wallander's role as team leader.

"I'm still a bit confused," Martinsson said, leafing through his papers. "But basically this is how it looks. On the morning of Wednesday, October 27, in other words five days ago, Mrs Berta Duner - secretary to the firm of solicitors - arrived for work as usual, a few minutes before 8 a.m. She found Sten Torstensson shot dead in his office. He was on the floor between the desk and the door. He had been hit by three bullets, each one of which would have been enough to kill him. As nobody lives in the building, which is an old stone-built house with thick walls, and located on a main road as well, nobody heard the shots. At least, nobody has come forward as yet. The preliminary post-mortem results indicate he was shot at around 11 p.m. That would fit in with Mrs Duner's statement to the effect that he often worked late at night, especially after his father died in such tragic circumstances."

Martinsson paused at this point and looked questioningly at Wallander.

"I know his father died in a road accident," Wallander said.

Martinsson nodded and continued: "That's more or less all we know. In other words, we know next to nothing. We don't have a motive, no murder weapon, no witness."

Wallander wondered if he ought to say something about Torstensson's visit to Skagen. All too often he had committed what was a cardinal sin for a police officer and held back information that he should have passed on to his colleagues. On each occasion, it's true, he reckoned that he had good grounds for keeping quiet, but he had to concede that his explanations had almost always been unconvincing.

I'm making a mistake, he thought. I'm starting my second life as a police officer by disowning everything previous experience has taught me. Nevertheless, something told him it was important in this particular case. He treated his instinct with respect. It could be one of his most reliable messengers, as well as his worst enemy. He was certain he was doing the right thing this time.

Something Martinsson had said made him prick up his ears. Or perhaps it was something he had not said.

His train of thought was interrupted by Bjork slamming his fist on the table. This normally meant that the Chief of Police was annoyed or impatient.

"I've asked for pastries," he said, "but there's no sign of them. I suggest we break off at this point and that you fill Kurt in on the details. We'll meet again this afternoon. We might even have something to go with our coffee by then."

When Bjork had left the room, they all gathered round the end of the table he had vacated. Wallander felt he had to say something. He had no right simply to barge in on the team and pretend nothing had happened.

"I'll try to start at the beginning," he said. "It's been a rough time. I honestly didn't think I'd ever be able to get back to work. Killing a man, even if it was in self-defence, hit me hard. But I'll do my best."

Nobody said a word.

"You mustn't think we don't understand," Martinsson said, at last. "Even if police work trains you to get used to just about everything, making you think there's no end to how awful life can be, it really strikes home when adversity lands on somebody you know well. If it makes you feel any better, I can tell you that we've missed you just as much as we missed Rydberg a few years ago."

Dear old Chief Inspector Rydberg, who died in the spring of 1991, had been their patron saint. Thanks to his enormous abilities as a police officer, and his willingness to treat everybody in a way that was both straightforward and personal, he had always been right at the heart of every investigation.

Wallander knew what Martinsson meant.

Wallander had been the only one who had grown so close to Rydberg that they had been good friends. Behind Rydberg's surly exterior was a person whose knowledge and experience went far beyond the criminal cases they investigated together.

I've inherited his status, Wallander thought. What Martinsson is really saying is that I should take on the mantle that Rydberg had, but never displayed publicly. Even invisible mantles exist.

Svedberg stood up.

"If nobody has any objection I'm going over to Torstensson's offices," he said. "Some people from the Bar Council have turned up and are going through his papers. They want a police officer to be present."

Martinsson slid a pile of case documents over to Wallander.

"This is all we've got so far," he said. "I expect you'd like a bit of peace and quiet to work your way through them."

Wallander nodded. "The road accident. Gustaf Torstensson."

Martinsson looked up at him in surprise. "That's finished and done with," he said. "The old fellow drove into a field."

"If you don't mind, I'd still like to see the reports," Wallander said, tentatively.

Martinsson shrugged. "I'll drop them off in Hanson's office."

"Not any more," Wallander said. "My old room is mine again."

Martinsson got to his feet. "You disappeared one day, and now you're back just as suddenly. Forgive the slip of the tongue."

Martinsson left the room. Only Wallander and Ann-Britt Hoglund were left now.

"I've heard a lot about you," she said.

"I'm sure what you've heard is absolutely true, I regret to say."

"I think I could learn a lot from you."

"I very much doubt that."

Wallander got hurriedly to his feet to cut short the conversation, gathering the papers he had been given by Martinsson. Hoglund held open the door for him. When he was back in his office and had closed the door behind him, he noticed he was running with sweat. He took off his jacket and shirt, and started drying himself on one of the curtains. Just then Martinsson opened the door without knocking. He hesitated when he caught sight of the half-naked Wallander.

"I was just bringing you the reports on Gustaf Torstensson's car accident," Martinsson said. "I forgot it wasn't Hanson's door any longer."

"I may be old-fashioned," Wallander said, "but please knock in future."

Martinsson put a file on Wallander's desk and beat a hasty retreat. Wallander finished drying himself, put on his shirt, then sat at his desk and started reading.

It was gone 10.30 by the time he finished the reports.

Everything felt unfamiliar. Where should he start? He thought back to Sten Torstensson, emerging out of the fog on the Jutland beach. He asked me for help, Wallander thought. He wanted me to find out what had happened to his father. An accident that was really something else, and not suicide. He talked about how his father's state of mind had seemed to change. A few days later he himself was shot in his office late at night. He had talked about his father being on edge, but he was not on edge himself.

Deep in thought, Wallander pulled towards him the notebook in which he had previously written Torstensson's name. He added another: Gustaf Torstensson. Then he wrote them again in the reverse order.

He picked up the phone and dialled Martinsson's number. No answer. He tried again, still no answer. Then it dawned on him that the numbers must have been changed while he was away. He walked down the corridor to Martinsson's office. The door was open.

"I've been through the investigation reports," he said, sitting down on Martinsson's rickety visitor's chair.

"Nothing much to go on, as you'll have noted," Martinsson said. "One or more intruders break into Torstensson's offices and shoot him. Apparently nothing was stolen. His wallet still in his inside pocket. Mrs Duner's been working there for more than 30 years and she is sure that nothing is missing."

Wallander nodded. He still hadn't unearthed what it was that Martinsson had said or not said earlier which had made him react.

"You were first on the scene, I suppose?" he said.

"Peters and Noren were there first, in fact," Martinsson said. "They sent for me."

"One usually gets a first impression on occasions like this," Wallander said. "What did you think?"

"Murder with intent to rob," Martinsson said without hesitation.

"How many of them were there?"

"We've found no evidence to suggest whether there was just one, or more than one. But only one weapon was used, we can be pretty sure of that, even if the technical reports are not all in yet."

"So, was it a man who broke in?"

"I think so," Martinsson said. "But that's just a gut feeling with nothing to support or reject it."

"Torstensson was hit by three bullets," Wallander said. "One in the heart, one in the stomach just below the navel, and one in his forehead. Am I right in thinking that that suggests a marksman who knew what he was doing?"

"That struck me too," Martinsson said. "But of course it could have been pure coincidence. They say death is caused just as often by random shots as by shots from a skilled marksman. I read that in some American report."

Wallander got to his feet. "Why should anybody want to break into a solicitor's office?" he asked. "Presumably because lawyers are said to earn huge amounts of money. But would anybody really expect to find the money piled up in their office?"

"There's only one or perhaps two persons who could answer that question," Martinsson said.

"We'll catch them," Wallander said. "I think I'll go there and have a look around."

"Mrs Duner is pretty shaken, naturally," Martinsson said. "In less than a month the whole fabric of her life has collapsed. First old man Torstensson dies. Hardly has she got over sorting out the funeral arrangements than his son is murdered. She's in shock, but even so it's surprisingly easy to talk to her. Her address is on the transcript of the conversation Svedberg had with her."

"Stickgatan 26," Wallander read. "That's just behind the Continental Hotel. I sometimes park there."

"Isn't that an offence?" Martinsson said.

Wallander collected his jacket and left the station. He had never seen the girl in reception before. He thought that perhaps he ought to have introduced himself. Not least to find out whether Ebba, who had been there for years, had stopped working evenings. But he let it pass. The time he had spent in the station so far today had seemed on the face of it to be nothing dramatic, but that did not reflect the tension inside him. He felt he needed to be on his own. For some considerable time now he had spent most of his days alone. He needed time to make the transformation. He drove down the hill towards the hospital, and just for a moment felt a vague yearning for the solitariness of Skagen, for his isolated sentry duty and his beach patrols that were guaranteed not to be disturbed.

But that was all in the past. He was back at work now.

I'm not used to it, he thought. It'll pass, even if it takes time.

The solicitors' offices were in a yellow-painted stone building in Sjomansgatan, not far from the old theatre that had been getting a facelift. A patrol car was parked outside, and on the opposite pavement a handful of onlookers were discussing what had happened. The wind was gusting in from the sea, and Wallander shuddered as he clambered out of his car. He opened the heavy front door and almost collided with Svedberg on his way out.

"I thought I'd get a bite to eat," he said.

"Go ahead," Wallander said. "I expect to be here for a while."

A young clerk was sitting in the front office with nothing to do. She looked anxious. Wallander remembered from the reports that her name was Sonia Lundin, and that she had been working there only a few months. She had not been able to provide the investigation with any useful information.

Wallander shook hands with her and introduced himself.

"I'm just going to take a look around," he said. "Mrs Duner's not here, I suppose?"

"She's at home, crying," the girl said.

Wallander had no idea what to say.

"She'll never survive all this," Lundin said. "She'll die too."

"Oh, I don't think so," Wallander said, conscious of how hollow his response sounded.

The Torstensson legal practice had been a workplace for solitary people, he thought. Gustaf Torstensson had been a widower for more than 15 years and so his son Sten had been without a mother all that time and was a bachelor to boot. Mrs Duner had been divorced since the early '70s. Three solitary people who came into contact with each other day after day. And now two of them were gone, leaving the third more alone than ever.

Wallander had no difficulty in understanding why Mrs Duner was at home crying.

The door to the meeting room was closed. Wallander could hear murmuring from inside. The lawyers' nameplates were on the doors on either side of the meeting room, fancily printed on highly polished brass plates.

On the spur of the moment he opened first the door to Gustaf Torstensson's office. The curtains were drawn and the room was in darkness. There was a faint aroma of cigar smoke. Wallander looked around and had the feeling that he had gone back to an earlier age. Heavy leather sofas, a marble table, paintings on the walls. It occurred to him that he had overlooked one possibility: that whoever murdered Sten Torstensson was there to steal the objets d'art. He walked up to one of the paintings and tried to decipher the signature, trying also to establish whether it was a copy or an original. Without having been successful on either count, he moved on. There was a large globe next to the solid-looking desk, which was empty, apart from some pens, a telephone and a Dictaphone. He sat in the comfortable desk chair and continued to look around the room, thinking again about what Sten Torstensson had said to him in the cafe at the Art Museum in Skagen.

A car accident that wasn't a car accident. A man who had spent the last months of his life trying to hide something that was worrying him.

Wallander asked himself what would be the characteristics of a solicitor's life. Supplying legal advice. Defending when a prosecutor prosecutes. A solicitor was always receiving confidential information. Lawyers were under a strict oath of confidentiality. It dawned on him that solicitors had a lot of secrets to keep. He hadn't thought of that before.

He got to his feet after a while. It was too soon to draw any conclusions.

Lundin was still sitting motionless on her chair. He opened the door to Sten Torstensson's office. He hesitated for a second, as if half expecting to see the dead man's body lying there on the floor, as it was in the photographs he had seen in the case reports, but all that was left was a plastic sheet. The technical team had taken the dark green carpet away with them.

The room was not unlike the one he had just left. The only obvious difference was a pair of visitors' chairs in front of the desk. This time Wallander refrained from sitting down. There were no papers on the desk.

I'm still only scraping at the surface, he thought. I feel as if I'm listening as much as I am trying to get my bearings by looking.

He went out to the reception area, closing the door behind him. Svedberg was back and was trying to persuade the girl to have one of his sandwiches. Wallander shook his head on being offered one as well. He pointed to the meeting room.

"In there are two worthy gentlemen from the Bar Council,'' Svedberg said. "They're working their way through all the documents in the place. They record, seal and wonder what to do about them. Clients will be contacted and other solicitors will take over their business. Torstensson Solicitors to all intents and purposes no longer exists."

"We must have access to all the material, of course," Wallander said. "The truth about what happened might well lie somewhere in their relationships with their clients."

Svedberg raised his eyebrows and looked at Wallander. "Their?" he said. "I expect you mean the son's clients."

"You're right. I do mean Sten Torstensson's clients."

"It's a pity really that it's not the other way round."

Wallander almost missed Svedberg's comment. "Why, what do you mean?"

"It would appear that old man Torstensson had very few clients," Svedberg said. "Sten Torstensson, on the other hand, was mixed up in all kinds of things." He nodded in the direction of the meeting room. "They think they'll need a week or more to get through it."

"I'd better not interrupt them, then," Wallander said. "I think I'd rather be having a word with Mrs Duner."

"Do you want me to come with you?"

"No need, I know where she lives."

Wallander went back to his car and started the engine. He was in two minds. Then he forced himself to come to a decision. He would start with the lead that nobody except him knew about. The lead Sten Torstensson had given him in Skagen.

They have to be connected, Wallander thought as he drove slowly eastwards, passed the courthouse and Sandskogen and soon left the town behind. These two deaths are linked. There is no other rational explanation.

He contemplated the grey landscape he was travelling through. It was drizzling. He turned up the heater.

How can anybody fall in love with all this mud? he wondered. But that's exactly what I have done. I am a police officer whose existence is forever hemmed in by mud. And I wouldn't change this countryside for all the tea in China.

It took him a little more than half an hour to get to the place where Gustaf Torstensson had died on the night of October 11. Wallander had the accident report with him, and stepped out on to the windy road with it in his pocket. He took out his Wellingtons and changed into them before he started scouting around. The wind was getting stronger, as was the rain, and he felt cold. A buzzard perched on a crooked fencing pole, watching him.

The scene of the accident was unusually desolate even for Skane. There was no sign of a farmhouse, nothing but undulating brown fields as far as the eye could see. The road was straight, then started to climb a hundred metres or so ahead before turning sharply left. Wallander unfolded the sketch of the scene of the accident, and compared the map with the ground itself. The wrecked car had been lying upside down to the left of the road, 20 metres into the field. There were no skid marks on the road. It had been thick fog when the accident occurred.

Wallander put the report back into the car before it got soaked. He walked to the crown of the road, and looked around. Not one car had gone past. The buzzard was still on its pole. Wallander jumped over the ditch and squelched his way across muddy clay that immediately clung to the soles of his boots. He paced out 20 metres and looked back towards the road. A butcher's van drove past, and then two cars. The rain was getting heavier all the time. He tried to envisage what had happened. A car with an old man driving is in the midst of a patch of thick fog. The driver loses control, the car leaves the road, spins round once or twice and ends up on its roof. The driver is dead, held into his seat by his safety belt. Apart from some grazing on his face, he has smashed the back of his head against some hard, projecting metallic object. In all probability death was instantaneous. He is not discovered until dawn the next day when a farmer passing on his tractor sees the car.

He need not have been going fast, Wallander thought. He might have lost control and hit the accelerator in panic. The car sped out into the field. What Martinsson wrote up about the scene of the accident was probably comprehensive and correct.

He was about to call it a day when he noticed something half buried in the mud. He bent down and saw that it was the leg of one of those brown wooden kitchen chairs. He threw it away, and the buzzard flew off from its pole, flapping away with its heavy wings.

There's still the wrecked car, Wallander thought, but I don't expect I'll find anything startling there that Martinsson has not noted already.