To Maria Mazur, my beloved wife and guardian muse.

You’re my endless inspiration, lighting and warming my soul.

My very first reader.

Without you, this novel would never come to be

and my smiles would’ve been fewer and farther between.

Phuket Island, Thailand

December 2004

International Hospital

Mother’s voice comforted Slava. Nothing bad could possibly come to him with her by his bedside.

“So you stay here overnight, Slava,” she told him. “It’s not that bad. You’re big enough to manage. We’ll come in the morning and take you home.”

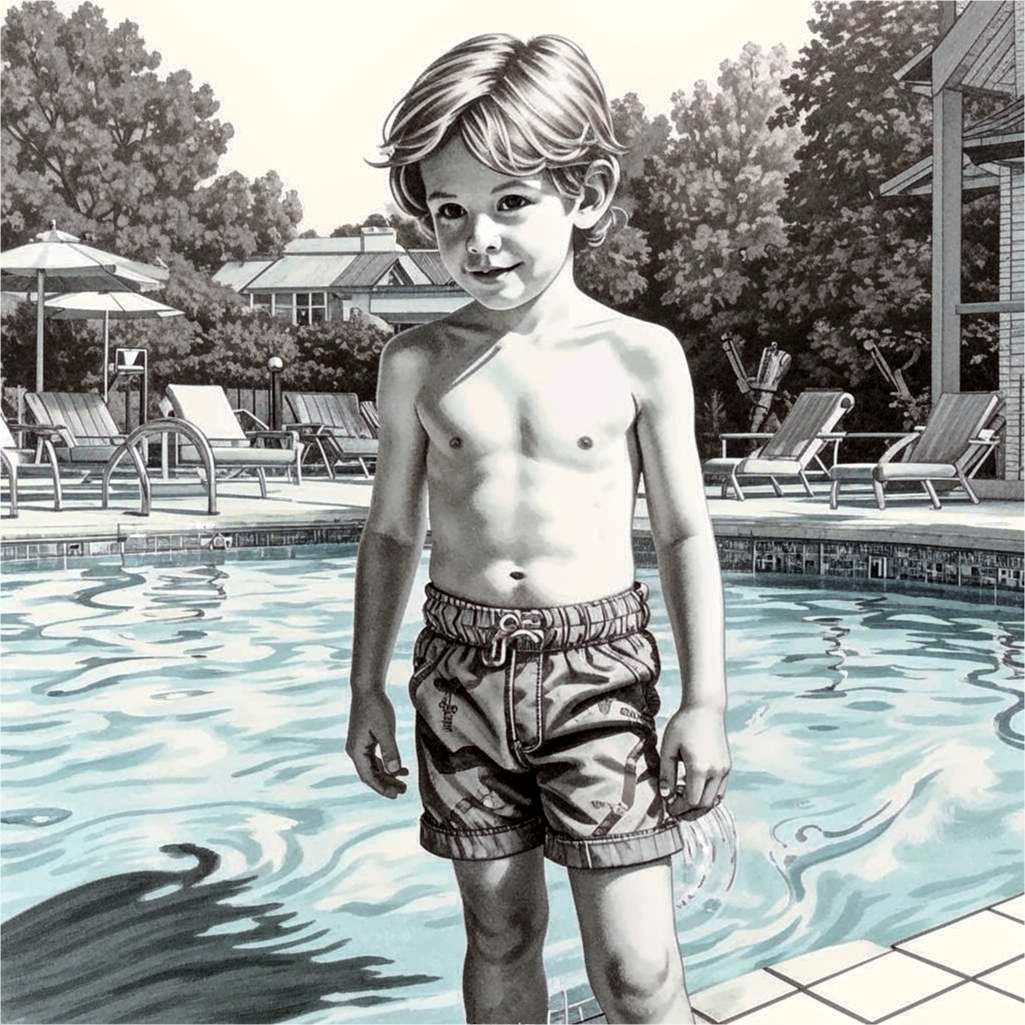

A boy of ten, Slava felt chilly from the burn ointment over his itching skin. As the medicine they’d given him was taking effect, he was overcame by an urge to sleep.

For the first time since their family had come to Thailand, he made no attempt to argue. That surprised Alyona, his younger sister, so much that she stared at him with pitiful eyes.

His stern father forced out a smile and ruffled the boy’s hair. “Hold on, trooper. Tomorrow you’ll feel better, and by New Year, it will fully heal. Why the hell did you have to get into that pool? We told you to stay in the room. We’re almost broke now—because of you. Our insurance doesn’t pay for sunburns. Sometimes you behave worse than Alyona.”

“Why me?” the seven-year-old girl protested. “It wasn’t me who got sunburned. Serves him well.”

“I stayed under the umbrella,” Slava mumbled, licking his blistered lips.

Over the hour he’d spent in the outdoor pool in the afternoon, he’d got sunburned to the point of his skin peeling off. As his parents and sister had been off to Phuket Town to get some stupid silicone pillows from the local mall, he’d hit the pool. The water was incredibly warm, clean, and transparent. A pure blessing to swim in. So much better than any pool he’d been to in Russia: indoor, cold, and overcrowded.

He just couldn’t get enough of that warm water in the hot sun.

“I just got distracted for a moment,” he added in his smallest voice.

It took as much as briefly closing his eyes to doze off—and miss the moment when the umbrella shadow was gone, exposing him to the sun. And here he was, badly burned without even hitting the beach. So unfair.

They’ll pay the next time they refuse to take me to the mall. I’ll throw a worse tantrum than Alyona.

“And please, Dad. I’m not Slava. I’m Tai.”

Tai was the new name he’d given himself two days ago, abbreviating the name of the country they’d come in for vacation. But none of the family seemed to care. They just kept using his old name.

Mother planted a kiss on his cheek and shut the curtain, separating him from another patient in the room.

Father looked around with a sigh. A stay in this large two-bed hospital room was to be paid by family money. All tourists coming to Thailand were warned their insurance didn’t cover sunburns.

The hospital treatment was anything but cheap, but it was their only option. The local shops didn’t have any sour cream, a Russian folk remedy for sunburns. And even if they had, it might’ve been useless against the harsh Thai sun.

The old Thai man on the other bed was no nuisance, but Slava could become exactly that upon recovery. He could come up to the stranger and shower him with lots of questions that the old man wouldn’t even understand. But, out of the particular respect that many Thai people had for small children, he could still try to answer them, smiling at Slava and making small gifts.

Slava was adept at getting strangers to like him, regardless of what language they spoke.

He’d begun to practice his English while still on the bus taking the family from the airport to the hotel. In less than an hour, he’d made friends with a sociable Dutch man, getting him to promise to accept the family as his guests once they came to Amsterdam. The bus stopping at their destination had come as a great relief to Slava’s parents who were not up to taking any other trips that soon, for financial reasons.

The family members left the ward, closing the door behind them. The air conditioner was working quietly, lulling Slava to sleep. He put his head down on the pillow and soon fell asleep on his belly. No way to turn over to his back as his nape and shoulders still hurt from the burns.

His last thought was a regret that he’d have to spend the rest of the vacation without ever taking his tee off. Or even grounded in the hotel room. No palm trees and ocean for him.

A loud noise from the hallway woke him. Slava had no idea how much time he’d slept; the hospital ward had no clock.

He heard many anxious voices outside the door, speaking English and Thai. Some even spoke Russian. He realized that something out-of-the-ordinary had happened, causing people to speak that loud in a hospital.

“What’s happened?” he cried out in Russian. Then repeated his question in English.

The curtain was open; it must’ve been the nurse coming in at night. He saw the impassive face of the old man who took the remote control unit and clicked the TV on.

Slava turned over to his side, overcoming pain, to see the screen.

It was a news broadcast, the presenters speaking Thai, but the big letters under their anxious faces read DISASTER HITS PHUKET in several languages, including English.

Looking for familiar English words in the news ticker, Slava felt his heart sink into the pit of his stomach, bringing a cold wave of sticky fear all over his body. He broke into tears before even realizing the gravity of the situation. The words he knew—tsunami, beach, missing, killed, destroyed—came together to form a bitter, heartbreaking picture.

“MOM!” Tai screamed. Where was his mother? His father? He had no idea whom to ask these questions to.

The screen was now showing destruction filmed from a helicopter. Swept-away houses. Destroyed hotels. Overturned cars. Uprooted lampposts and palm trees. As though by purpose, the camera took the familiar red-tiled roof of the hotel where Slava’s family had stayed, with its cozy balconies, a water tower nearby, and the conspicuous flag with the hotel name.

“NO!” the boy screamed and buried his face in the pillow, crying loudly.

The door swung open. Slava was about to run up to the doctor, begging him to reach out to his parents, but shrunk back at seeing the bloodied, half-naked male body on the trolley. The man’s arm was blue and black, a broken piece of wood stuck in his biceps, his face blue and swollen the same.

Only for a split second had Slava seen that, but it was enough for the sight to get engraved in his mind.

Closing his eyes, he buried his face in the pillow, struggling to contain his sobs. He was too big to cry aloud in front of the old man, but not big enough to pretend everything was all right. He wasn’t that good at self-deception.

The world seemed to become less real, more of a horror movie.

That was how Slava Demchenko became one of the many thousand international tourists in Thailand whose hopes of a happy New Year 2005 celebration in this country were swept away by the giant wave hitting the island of Phuket and then the coast.

While the day of December 26th was breaking in Thailand, the small waves raised by a strong earthquake at the bottom of the Indian Ocean went rushing for the nearby coasts, slowing down as they approached the land but swelling up to the size of multi-story buildings to crash their million-gallon weight of seawater down on the beaches of Phuket, Krabi, Phi Phi, Similan, Ko Chang, and Phang Nga, wreaking chaos, death, and destruction.

Almost all large beaches in the Western Phuket were hit by the tsunami, with Kamala, Patong, Karon, and Kata taking the worst of it. Many hotels close to the water were swept away by the wave, including the one where Slava’s family was staying.

Back at that moment he, and the old Thai man, just got rolled out in their beds into the crowded hallway of the hospital where all rooms were now freed to accommodate the disaster victims, many of whom were seriously injured.

In the crammed hallway filled with injured people and bustling medical workers, the boy—for the first time in his life—saw human grief come out through screaming, tears, moans, prayers, and curses.

Within the hour following the earthquake, the island had been warning its inhabitants. The animals were running away into the jungle and climbing the mountains, the birds leaving their nests. The sound of the surf stopped suddenly as the tide went out and far away. The thrilled observers came out onto the exposed sea bottom to collect shells, crabs, shrimps, and small fish.

The oncoming wall of water had remained unnoticed until it was too late to escape. The wave had no foamy crest, being transparent and invisible against the azure-blue backdrop of the calm sea and the sky merging in the distance.

Then the tsunami came into view, sweeping several miles into the island and destroying everything in its way like Poseidon’s rage, or like the Grim Reaper’s scythe.

Then the flood seemed to retreat, but it was a deceptive move. The tsunami rolled back just to crash down again, with greater strength, washing away and into the ocean those who’d survived the first wave.

Humans and animals were thrown onto the buildings, grinded with a mixture of earth and concrete, pierced through by exposed fittings and sharp wood, smashed on billboards and cars, or killed by electric shock from the torn high-voltage cables until electricity was cut off. The crazy water spared no one.

It was Phuket’s blackest day.

After the tsunami left, there were the ravaged beaches, cars on the trees and hotel walls atop the hills. Boats were found in the jungle two miles away from the coast. No coastal building was spared. The remains of houses and streets were covered with sand, scum, seaweed, and earth, the flood carrying pieces of furniture, local merchandise, clothes, and food. The street vendors’ overturned carts could be seen on the balconies. But the worst thing were the dead human and animal bodies scattered everywhere, among dead fish and seafood.

Playing that over and over again in his mind, Tai felt like losing his sanity. His soul was consumed by grief and pain as he realized that his entire family was probably dead. This tide of emotion was so overwhelming that it turned his hair gray.

In a nervous breakdown, Tai pulled out a clump of his hair. As he stared at the gray, curly strand, he realized he could no longer stay in the hospital.

“I must go,” he whispered to himself.

He was seeing double.

The people around him all had glowing doubles of different colors, mostly dark-red, violet, or navy-blue. These doubles were fluttering around their bodies, stretching up to the ceiling or shrinking to the size of a pea as they constantly changed shape.

Dismissing that as a hallucination, Tai removed his blanket and stood. No one seemed to pay any heed in this crowd of people requiring urgent medical assistance as he put on his shorts, then his tee, clenching his teeth as his nape, shoulders, and back ached to the touch of the fabric. Then he covered his gray hair with a baseball cap, slipped his feet into sandals, and walked off toward the exit.

The pain filling Tai’s body reminded him that he was still alive.

Following this pain, he walked and walked, leaving behind the tumultuous hallways flooded with pain, the no-service elevators, and the stairs, slipping through the space like a water drop would slip through sand.

But out in the street, things were even weirder.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ