PART FIVE: THE STRANGE DEATH OF MIHAILOV

CHAPTER 1

THE WORKINGS OF A CLASS III ROBOT are as surpassingly complex as they are surpassingly small. As is well known, each of these miraculous humanoid automatons contains within itself a self-perpetuating system of systems, a universe of infinitesimal mechanisms, and the movement of these intricately interconnected contraptions is powered by the “sun” that sits at the core of every Class III. That sun is the groznium engine, the approximate size and proportion of a human heart, which burns for the life of the machine with furious intensity. It is that remarkable heat-giving heart, unseen from without but all-powerful within, that gives life to the machine, generating the energy to turn the gears to animate the thousands of interlocking parts creating the easy, fluid functioning of a companion robot.

So, too, goes the working of our universe. God’s will in the world is like that unseen groznium fire-its heat and power forever surrounding us, suffusing every new event and idea. Whether we know it or not, we are but servomechanisms in the service of fate, and our movements, our very thoughts, are powered only by the magnificent heat shed by the Almighty.

And so, just as a Class III performs its variety of ever-changing duties with seeming intelligence and independence, we humans may attempt in our arrogance to steer the events of the world, but never can we indeed control those events-they will continue along their own way, along God’s way, no matter the fervency of our desires or the force of our expectations. We are but gears, turned only by the unseen hand of the Lord.

The Higher Branches of the Ministry, led by Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin, now unquestionably their dominant figure, moved forward with the momentous Project: the collection of all Class III robots to undergo “adjustments,” the precise nature of which were still a great mystery to the public in general, who would be affected. Softening the blow was the civil and decorous manner of the young officers assigned to enact the adjustment provision; reportedly recruited from the highest ranks of the Caretakers, these young men soon became known as Toy Soldiers, what with their neatly pressed blue uniforms and slim black boots. In pairs or groups of three they appeared on doorsteps all over the country, inquiring respectfully whether any Class III robots were among the household. With handheld Class I devices they diligently recorded the names and generational information of each beloved-companion, and carefully provided a receipt before the machine was loaded in the back of a coach.

Anyone who thought to question the Toy Soldiers as to the precise nature of the planned circuitry “adjustments” was told firmly but with gentleness that such concerns were the responsibility of the Ministry, and wouldn’t we all do well to put our trust in our leaders? In general, this response was considered satisfactory, and the people accepted their receipts and bade calm farewell to their Class Ills.

Even Stepan Arkadyich Oblonsky, whose beloved-companion Small Stiva flashed his usually cheerful eyebank tremulously as he was led away, waved merrily and called out, “Never fear, little Samovar. I shall see you again soon.” Stepan Arkadyich tried mightily, by dint of a peculiar internal ability he cherished, to block out unpleasant thoughts and associations, to forget what he had seen in Karenin’s basement office in the Moscow Tower. There could be no connection, he assured himself, between Karenin’s strange experiments and what was happening now. “Wouldn’t we all do well to put our trust in our leaders?” he chastened his tearful wife, Darya Alexandrovna, as her kind and matronly Dolichka was led away.

“Wouldn’t we?”

CHAPTER 2

THE GEARS OF LIFE turned and turned again, ever forward, and in time the anxious confusion surrounding the departure of Small Stiva and Dolichka was replaced in the household of Oblonsky by joyful anticipation, as preparations began for the wedding of Dolly’s sister, Kitty Shcherbatskaya, to Stepan’s oldest friend, Konstantin Dmitrich Levin.

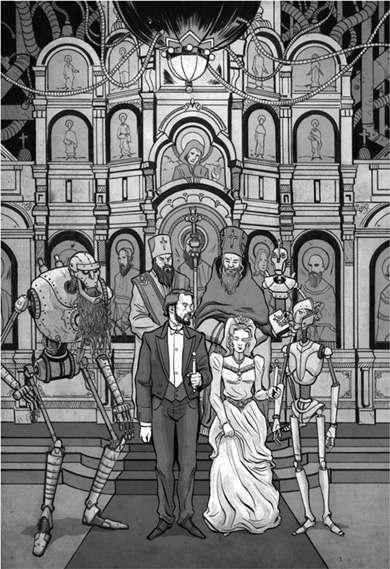

When they arrived at the church, a crowd of people, principally women, was thronging round the church lighted up for the wedding. Those who had not succeeded in getting into the main entrance were crowding about the windows, pushing, wrangling, and peeping through the gratings.

More than twenty carriages had already been drawn up in ranks along the street by the Class II police robots, their bronze weather-protected outercoating primed against the rusting frost. More carriages were continually driving up, and ladies wearing flowers and carrying their trains, and men taking off their helmets or black hats kept walking into the church. The church windows, programmed for the occasion by a highly sought-after display gadgeteer, glowed brightly with the life of the Savior, one luminously delineated scene shifting seamlessly into the next. This ornate display, along with the gilt on the red background of the holy picture-stand, the silver of the lusters, and the stones of the floor, and the rugs, and the banners above in the choir, the steps of the altar, the cassocks and surplices-all were flooded with light.

The only thing missing was the loving couple. Every time there was heard the creak of the opened door, the conversation in the crowd died away, and everybody looked round expecting to see the bride and bridegroom come in. But the door had opened more than ten times, and each time it was either a belated guest or guests, who joined the circle of the invited on the right, or a spectator, who had eluded the II/Policeman/56s, and went to join the crowd of outsiders on the left. The Galena Box sent its waves of oscillation through the room, but was proving insufficient to dampen the mood of confused anxiety; both the guests and the outside public had by now passed through all the phases of anticipation. The long delay began to be positively discomforting, and relations and guests tried to look as if they were not thinking of the bridegroom but were engrossed in conversation.

At last one of the ladies, glancing at her I/Hourprotector/8, said, “It really is strange, though!” and all the guests became uneasy and began loudly expressing their wonder and dissatisfaction.

Kitty meanwhile had long ago been quite ready, and in her white dress and long veil and wreath of orange blossoms she was standing in the drawing room of the Shcherbatskys’ house. Beside her was her pink-flushed Class III, Tatiana, one of the last beloved-companions left in Moscow. Kitty had been allowed to forestall her Class III’s collection for “adjustment” until after the wedding, thanks to the intercession of her father, Prince Shcherbatsky with a childhood friend who sat on the Higher Branches. (“A girl cannot be wed without the soothful presence of her Class III,” the prince had pleaded; meanwhile, all across Russia, less well-connected brides were somehow making do.) Tatiana was looking out of the window, and had been for more than half an hour piping a soft and calming lullaby from her Third Bay, to keep her mistress from becoming too anxious that her bridegroom was not yet at the church.

Levin meanwhile, in his trousers, but without his coat and waistcoat, was walking to and fro in his room at the hotel, with Socrates pacing directly behind him, his beard clanking. (He, too, had been granted a reprieve, exhausting the favors due to the old prince). Man and machine took turns poking their heads out of the door and looking up and down the corridor. But in the corridor there was no sign of the Class II who had been dispatched to bring Levin his shirtfront, which had been forgotten. The shirtfront had been left at home by Levin’s best man, Stepan Arkadyich, who placed the blame on Small Stiva-or rather, the absence of Small Stiva. Oblonsky had assumed that his beloved-companion, ever mindful of such details, would bring the necessary accoutrements, and it slipped his mind entirely that his dear friend was by now at a Robot Processing Facility in Vladivostok, in deep Surcease with his mechanical guts splayed out on a workbench.

While Socrates frantically paced, Levin addressed Stepan Arkadyich, who was smoking serenely.

“Was ever a man in such a fearful fool’s position?” he said.

“Yes, it is stupid, and I feel awful,” Stepan Arkadyich assented, smiling soothingly. “I’m a simple block of wood without my Little Samovar. But don’t worry, it’ll be brought directly.”

“No, what is to be done!” said Levin, with smothered fury. “What if it’s been lost?”

“It’s not been lost,” reassured Stepan Arkadyich.

“It may have been lost. Yes, probably it’s lost,” intoned Socrates.

“That is not helpful,” said Stepan Arkadyich with a glare suggesting a wish that Socrates, too, were in a Vladivostok R.P.F. Addressing himself to Levin, he said: “Just wait a bit! It will come round.”

And so while the bridegroom was expected at the church, he was pacing about his room like a caged Huntbear, peeping out into the corridor, and with horror and despair recalling what absurd things he had said to Kitty and what she might be thinking now.

At last the II/Runner/470 zipped into the room with the shirt held aloft from a pincer, like a dog with a bagged quail. Three minutes later Levin ran full speed into the corridor not looking at his I/Hourprotector/8 for fear of aggravating his sufferings.

“It’s eleven thirty…,” moaned Socrates, motoring quickly behind him. “eleven thirty-one! We are very late, very late indeed!”

“Not helpful,” sighed Stepan Arkadyich as he tossed his cigarette into an ashtray, where it sputtered, hissed, and disappeared. “Not helpful at all.”

CHAPTER 3

“THEY’VE COME!” “Here he is!” “Which one? The tall yellow robot?” “No, fool! The robot’s master!” “Rather young, eh?” were the comments in the crowd, when Levin at last walked with Socrates into the church.

Stepan Arkadyich told his wife the cause of the delay, and the guests were whispering it with smiles to one another. Levin saw nothing and no one; he did not take his eyes off his bride as she walked up the aisle toward him.

Everyone said she had lost her looks dreadfully of late, and was not nearly so pretty on her wedding day as usual; but Levin did not think so. He looked at her hair done up high, with the long white veil and white flowers and the high, stand-up, scalloped collar, her strikingly slender figure, and it seemed to him that she looked better than ever-not because her beauty was accented by these flowers, this veil, this gown from Paris, and by the gentle pink backlight shed by Tatiana-but because, in spite of the elaborate sumptuousness of her attire, the expression of her sweet face, of her eyes, of her lips was still her own characteristic expression of guileless truthfulness.

“I was beginning to think you meant to run away,” she said, and smiled at him.

“It’s so stupid, what happened to me, I’m ashamed to speak of it!” he said, reddening.

Dolly came up, tried to say something, but could not speak, cried, and then laughed unnaturally. She was more affected than she had anticipated by the absence of Dolichka. How perfectly ridiculous, she thought, to have no nimble metal fingers to hand her tissues, no strong metal shoulder to lean on, at her own sister’s wedding!

Kitty looked at her, and at all the guests, with the same absent eyes as Levin.

Meanwhile the officiating clergy had gotten into their vestments, and the priest and deacon came out to the lectern, which stood in the forepart of the church. The priest turned to Levin saying something, but it was a long while before Levin could make out what was expected of him. For a long time they tried to set him right and made him begin again-because he kept taking Kitty by the wrong arm or with the wrong arm-till he understood at last that what he had to do was, without changing his position, to take her right hand in his right hand. When at last he had taken the bride’s hand in the correct way, the priest walked a few paces in front of them and stopped at the lectern. The crowd of friends and relations moved after them, with a buzz of talk and a rustle of skirts. Someone stooped down and pulled out the bride’s train. The church became so still that one could hear the faint buzz of the I/Lumiére/7s in their sconces.

All eyes were fixed upon the altar, and no one noticed that outside the church, the II/Policeman/56s were motoring in arbitrary circles, periodically colliding harmlessly, a sure sign of having been severely, and purposefully, maltuned.

The little old priest in his ecclesiastical cap, with his long, silverygray locks of hair parted behind his ears, was fumbling with something at the lectern. “Drat it, Saint Peter, where’d’ya keep the things?” he muttered in frustration; but while the church’s sacramental robot had been permitted to remain in its place at the altar, its analytical core had been removed for the Ministry’s adjustment. At last the priest put out his little old hands from under the heavy silver vestment with the gold cross on the back of it.

“A GIRL CANNOT BE WED WITHOUT THE SOOTHFUL PRESENCE OF HER CLASS III,” THE PRINCE HAD PLEADED

The priest initiated two I/Lumiére/7s, wreathed with flowers, and faced the bridal pair. He looked with weary and melancholy eyes at the bride and bridegroom, sighed, and putting his right hand out from his vestment, blessed the bridegroom with it, and also with a shade of solicitous tenderness laid the crossed fingers on the bowed head of Kitty. Then he gave them the lumiéres, and taking the censer, moved slowly away from them.

“Can it be true?” thought Levin, and he looked round at his bride. Looking down at her he saw her face in profile, and from the scarcely perceptible quiver of her lips and eyelashes he knew she was aware of his eyes upon her.

She did not look round, but the high, scalloped collar, which reached her little pink ear, trembled faintly. He saw that a sigh was held back in her throat, and the little hand in the long glove shook as it held the thin illuminated Class I.

All the fuss of the shirt, of being late, all the talk of friends and relations, their annoyance, his ludicrous position-all suddenly passed away and he was filled with joy and dread.

It was that precise cocktail of strong feeling that triggered the first of the emotion bombs.

It exploded with pinpoint precision beneath the seat of a single parishioner, an elderly second cousin of Kitty’s seated in the third pew from the back. The blast unleashed all the destructive force of a traditional explosion, but all concentrated on this one unfortunate soul, furiously vibrating every molecule in his body and turning his insides to a gelatinous paste. So precise was this terrible blast of force, however, that even the parishioners to the left and right of the man did not realize what had transpired, that the wedding was suddenly under attack by agents of UnConSciya. The wedding guest simply slumped forward in his seat, and might have been sleeping: an impolite but hardly shocking action by an elderly man at a church service.

“Blessed be the name of the Lord,” the solemn syllables rang out slowly one after another, as the priest intoned the liturgy, setting the air quivering with waves of sound. The brains of the murdered second cousin, essentially turned to liquid, leaked slowly from his ears.

“Blessed is the name of our God, from the beginning, is now, and ever shall be,” the little old priest said in a submissive, piping voice, still fingering something at the lectern. And the full chorus of the unseen choir rose up, filling the whole church, from the windows to the vaulted roof, drowning out a lone woman’s panicked shrieking from the back of the church.

“This man is dead! My God, what has-what’s happened?!”

A second emotion bomb ignited, this time beneath a young peasant woman with her head wrapped in colorful scarves-like the elderly relative, she collapsed in her place, her insides instantly emulsified.

The triumphant and praiseful sound of the choir grew ever stronger, and joy and mystery swelled in the bosoms of Levin and his bride, amplifying the danger for all present. The officiants prayed, as they always do, for peace from on high and for salvation; for the long life of the Higher Branches they prayed; and for the servants of God, Konstantin and Ekaterina, now pledging their troth. The closer the liturgy drew to the fateful moment, when Kitty and Levin would together enter the mysterious country of matrimonial connection, the more palpable was the bubbling admixture of dread and joy in their respective hearts; and with every upswell of that queer emotional tide, more of the quiet, precise bombs went off, each one more brutally effective than the last. Kitty and Levin stared into each other’s eyes, lost in tender feeling and contemplation of their intertwined fates, as the grim toll of their love grew every second.

“Vouchsafe to them love made perfect, peace and help, O Lord, we beseech Thee,” came the voice of the head deacon. Levin heard the words, and they impressed him.

“How did they guess that it is help, just help that one wants?” he whispered to Socrates, who stood faithfully at his elbow.

“Help!” cried Princess Shcherbatskaya. “My Lord, help!” Her sister, Kitty’s aunt, had suddenly jerked in her seat, twisted her body unnaturally, and tumbled forward into the princess’s lap. Levin and Kitty wheeled around from the altar, at last to behold the bedlam unfolding around them: a horror becoming worse every moment, as dread-joy bombs went off like celebratory I/Flashpop/4s at a child’s birthday party. Kitty screamed, her hands clutching at the side of her face in horror, as another explosion-no longer silent, indeed, louder than a sky full of thunder-shattered the electronically programmed window, sending shards of Savior-emblazoned glass raining down.

The first decisive action to stem the tide of violence came from the two beloved-companion robots. In a single smooth gambol, Tatiana tackled her mistress to the ground and arched backward into a bridge to protect her from the hail of glass. Socrates, plucking a well-worn physiometer from the tangle of tools in his beard, waded into the crowd to begin triage, and Levin could only rush to keep up.

“Why does it continue?” Kitty shouted to Levin, as he and his faithful machine-man surveyed the damage and tended to the wailing wounded. “If this is an emotion bombing”-for such was the only logical conclusion-“and if the bombs are fed by our joy at entering the blessed state of marriage, then why have they not stopped, now that our happiness is entirely subsumed?” Tatiana, meanwhile, with fluttering phalangeals deflected a fresh rain of glass and splintered wood.

Levin smiled despite himself. What a woman! How clever she is, to make such an astute analysis amid such dreadful circumstances. “Oh, God,” he said in sudden horror. “It’s me. I am happy! Heavenly Father, forgive me, but I am happy! I look at her, and even in such straits I cannot help it: I love her, and I feel joy!”

As if in grim confirmation of Levin’s realization, at the moment he uttered the word “joy” a blast rattled the back of the hall.

He looked about him in horror, marveling at the power of his love, trying and failing to squelch its power in his breast; and then Kitty lunged at him, her gown of lush white and lace billowing out behind her, clawing feverishly at his eyes and pulling viciously at his beard. Levin, shocked, covered his head against the onslaught, and, in that wild, pained instant, he was so surprised at her assault that his love for Kitty transformed into its opposite.

“Stop it,” he shouted at his beloved. “For God’s sake, stop! Are you insane?”

He grasped her wrists to cease the onslaught; she collapsed, spent, against his chest, weeping. Socrates looked up, beeping questioningly in the sudden hush that followed.

For as Konstantin Dmitrich’s joy waned, so had the attack. The emotion bombs were silenced and the devastated church grew silent and terribly still, but for the moaning and weeping of the wounded.

“She is a very capable woman,” said Socrates, admiringly.

“To be sure, old friend,” Levin agreed, stroking her hair. “As capable and intelligent as she is-”

Boom! A rafter cracked above the apse, and a displaced I/Lumiére/7 hurtled down from above.

“Master, let us remove you from this place.”

Twenty minutes later, outside the rubble of the church, the surviving officiant concluded the ceremony in a melancholy spirit. Kitty and Levin stood with laced hands, bruised and tearful, but unwilling-in the ancient Russian spirit-to let the terrorists of UnConSciya ruin their sacred day of union.

And so the old priest turned to the bridal pair and began: “Eternal God, who joinest together in love those who were separate,” he said in a sad, piping voice, as voices wailed in the background, “who hast ordained the union of holy wedlock that cannot be set asunder, Thou who didst bless Isaac and Rebecca and their descendants, according to Thy Holy Covenant; bless Thy servants, Konstantin and Ekaterina, leading them in the path of all good works. For gracious and merciful art Thou, our Lord, and glory be to Thee, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, now and ever shall be.”

Even as the ancient words were intoned, within the church the ragged and helpless victims awaited the inevitable arrival of a Caretaker with his troupe of 77s, who always arrived in the aftermath of such horrors. They wept for their injuries, for the continued plague of UnConSciya upon society; and they wept bitterly that their Class Ills had not been there to protect them, and were not there now to lend them support and comfort.

The violent disorder of his wedding day could not help but have its effect on Konstantin Dmitrich’s romantic ideas about marriage, and the life he was now to lead. Levin felt more and more that all his ideas of marriage, all his dreams of how he would order his life, were mere childishness, and that it was something he had not understood hitherto, and now understood less than ever, though it was being performed upon him. The lump in his throat rose higher and higher; tears that would not be checked came into his eyes.

After supper, the same night, the young people left for the country.

CHAPTER 4

VRONSKY AND ANNA had been traveling for three months together on the surface of the moon. They had visited the Mare Tranquillitatis and the famous canals of St. Catherine, and had just arrived at a hotel, part of the small farside colony where they meant to stay some time.

A Moonie, one of the weird, wiry Class IIs with bulbous glowing head units employed in nearly all man-serving positions on the moon’s surface, stood with his hands in the full curve of his silver outercoating, giving some frigid reply to a gentleman in a coarse engineer’s jumpsuit who had stopped him. Catching the sound of footsteps coming from the other side of the entry toward the staircase, the Moonie swiveled his big, bright ball of a head and, seeing the Russian count, who had taken their best rooms, with a bow informed him that a communiqué had been received: the business about the module he and his companion planned to rent had all been arranged.

“Ah! I’m glad to hear it,” said Vronsky. “Is madame at home or not?”

“Madame… went out for walk… but returned now,” answered the Class II in the distinctive stop-start manner of the Moonie.

Vronsky took off his soft, wide-brimmed hat and passed his handkerchief over his heated brow and hair, which had grown half over his ears, and was brushed back covering the bald patch on his head. And glancing casually at the gentleman, who still stood there gazing intently at him, he almost moved on.

“This gentleman… a Russian… inquiring after you.”

With mingled feelings of annoyance at never being able to get away from acquaintances anywhere, and longing to find some sort of diversion from the monotony of his life, Vronsky looked over at the gentleman, who had retreated and stood still again. Lupo, instinctually distrustful of strangers, leaned back on his haunches and bared his teeth at the stranger; but Vronsky, recognizing the man, whistled a sharp “stand down” to his Class III and smiled broadly.

“Golenishtchev!”

“Vronsky!”

Surprising though it was, it really was Golenishtchev, a comrade of Vronsky’s from the Corps of Pages. Golenishtchev and Vronsky had gone completely different ways on leaving the corps, and had only met once since, and had not gotten along. But now they beamed and exclaimed with delight on recognizing one another. Vronsky would never have expected to be so pleased to see Golenishtchev, but probably he was not himself aware how bored he was, so many space-versts from home, with only Anna for human company. With a face of frank delight he held out his hand to his old comrade, and the same expression of delight replaced the look of uneasiness on Golenishtchev’s face.

“How glad I am to meet you!” said Vronsky, showing his strong white teeth in a friendly smile.

“I heard the name Vronsky, but I didn’t know which one. I’m very, very glad!”

“Let’s go in. Come, tell me what you’re doing.”

“Digging, friend! Digging and digging and digging.”

Now Vronsky understood the reason for the dust-caked jumpsuit; Golenishtchev, a trained excavation and extraction engineer, had received a license from the Ministry’s Extra-Orbital Branch to plumb huge tracts of the lunar surface in search of the Miracle Metal-on the theory that, if it had mysteriously appeared in the Russian soil, and if the Russians in their ingeniousness had utilized groznium-derived technologies to land men on the moon, surely the Miracle Metal would one day be found there as well; although, Golenishtchev reported with a sad shrug, so far he had found only moon-rocks and dust.

“Ah!” said Vronsky, with sympathy, before deciding to broach the difficult subject, which he knew would come up sooner or later with any acquaintance. “Do you know Madame Karenina? We are traveling together. I am going to see her now,” he said, carefully scrutinizing Golenishtchev’s face.

“Ah! I did not know,” Golenishtchev answered carelessly, though he did know, and excused himself to ask a question of the obsequious Moonie.

“Yes, he’s a decent fellow, and will look at the thing properly,” Vronsky said happily to Lupo. “I can introduce him to Anna, he looks at it properly.”

During these weeks that Vronsky had spent on the moon, he had always on meeting new people asked himself how the new person would look at his relations with Anna, and for the most part, in men, he had met with the “proper” way of looking at it. But if either he or those who looked at it “properly” had been asked exactly how they did look at it, both he and they would have been greatly puzzled to answer.

In reality, those who in Vronsky’s opinion had the “proper” view had no sort of view at all, but behaved in general as well-bred persons do behave in regard to all the complex and insoluble problems with which life is encompassed on all sides; they behaved with propriety, avoiding allusions and unpleasant questions. They assumed an air of fully comprehending the import and force of the situation, of accepting and even approving of it, but of considering it superfluous and uncalled for to put all this into words.

Vronsky at once divined that Golenishtchev was of this class, and therefore was doubly pleased to see him. And in fact, Golenishtchev’s manner toward Madame Karenina and her android, when he was taken to call on them, was all that Vronsky could have desired. Obviously without the slightest effort he steered clear of all subjects that might lead to embarrassment. He had never met Anna before, and was struck by her beauty and the sleek lines of her beloved-companion, and still more by the frankness with which the woman accepted her position. She blushed when Vronsky brought in the rough-hewn Golenishtchev, his everlit helmet dangling from its chinstrap, his I/Shovelhoe/40(b) clanking at his side, and he was extremely charmed by this childish blush overspreading her candid and handsome face. But what he liked particularly was the way in which at once, as though on purpose that there might be no misunderstanding with an outsider, she called Vronsky simply Alexei, and said they were moving into a house they had just taken, what was here called a module. Golenishtchev liked this direct and simple attitude toward her own position. Looking at Anna’s manner of simple-hearted, spirited gaiety, Golenishtchev fancied that he understood her perfectly. He fancied that he understood what she was utterly unable to understand: how it was that, having made her husband wretched, having abandoned him and her son and lost her good name, she yet felt full of spirits, gaiety, and happiness.

“I tell you what: it’s a lovely day, let’s go and have another look at the module,” said Vronsky, addressing Anna.

“I shall be very glad to; I’ll go and find my helmet. And how is the gravity today?” she said, stopping short in the doorway and looking inquiringly at Vronsky. Again a vivid flush overspread her face.

Vronsky saw from the way her eyes would not meet his, resting instead on Android Karenina’s reassuring and familiar faceplate, that she did not know on what terms he cared to be with Golenishtchev, and so was afraid of not behaving as he would wish.

He looked a long, tender look at her. “The gravity is extremely fine,” he said. “All that could be wished for.”

And it seemed to her that she understood everything, most of all that he was pleased with her; and smiling to him, she walked with her rapid step out the door, Android Karenina whizzing along with equal confidence behind her. Vronsky and his old acquaintance glanced at one another, and a look of hesitation came into both faces, as though Golenishtchev, unmistakably admiring her, would have liked to say something about her, and could not find the right thing to say, while Vronsky desired and dreaded his doing so.

ANNA EMERGED IN PERAMBULATING TOGS, HER PALE AND LOVELY HAND HOLDING THE HANDLE OF HER DAINTY LADIES’-SIZE OXYGEN TANK

Anna excused herself to put on her perambulating togs. It was a rather cumbersome and complicated outfit, but every piece was entirely necessary: the oxygen tanks; the heavy, treaded boots; the asbestos-lined undersuit; and of course the sturdy, airtight helmet of reinforced glass. When Anna emerged, her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank, it was with a feeling of relief that Vronsky broke away from the plaintive eyes of Golenishtchev, and with a fresh rush of love looked at his charming companion, full of life and happiness.

They walked to the module they had reserved, and looked over it, Golenishtchev pompously taking the role of chief inspector, carefully examining the sealing systems and hatches, having vastly more experience than they with lunar living.

“I am very glad of one thing,” said Anna to Golenishtchev when they were on their way back. “Alexei will have a capital atelier. You must certainly take that module,” she said to Vronsky in Russian, using the affectionately familiar form as though she saw that Golenishtchev would become intimate with them in their isolation, and that there was no need of reserve before him.

“Do you paint?” said Golenishtchev, turning round quickly to Vronsky.

“Yes, I used to study long ago, and now I have begun to do a little,” said Vronsky, reddening.

“He has great talent,” said Anna with a delighted smile, and Lupo yipped his proud agreement. “I’m no judge, of course. But good judges have said the same.”

CHAPTER 5

ANNA, IN THAT PERIOD of her emancipation and rapid return to health, after her dangerous confinement and delivery, had felt herself unpardonably happy and full of the joy of life. The memory of all that had happened after her illness: her reconciliation with her husband, its breakdown, the news of Vronsky’s wound, his visit, the preparations for divorce, the departure from her husband’s house, the parting from her son, traveling to the moon inside an ovoid canister shot from a giant cannon-all that seemed to her like a delirious dream, from which she had woken up alone with Vronsky on the lunar surface. The thought of the harm caused to her husband aroused in her a feeling like repulsion, and akin to what a drowning man might feel who has shaken off another man clinging to him. That man did drown. It was an evil action, of course, but it was the sole means of escape, and better not to brood over these fearful facts.

One consolatory reflection upon her conduct had occurred to her at the first moment of the final rupture, and when now she recalled all the past, she remembered that one reflection. “I have inevitably made that man wretched, but I don’t want to profit by his misery,” she mused, while Android Karenina’s slim fingers braided her hair into charming plaits. “I too am suffering, and shall suffer; I am losing what I prized above everything-I am losing my good name and my son. I have done wrong, and so I don’t want happiness, I don’t want a divorce, and shall suffer from my shame and the separation from my child.”

Android Karenina nodded kindly, her eyebank glittering from deep red to sympathetic lilac. But she knew as well as her mistress that, although Anna had expected to suffer, she was not suffering. Shame there was not. She and Vronsky had never placed themselves in a false position, and everywhere they had met people who pretended that they perfectly understood their position, far better indeed than they did themselves. It was not by accident that they had traveled to the moon, a permissive enclave where judgment, along with gravity, held only a fraction of its usual force. Separation from the son she loved-even that did not cause her anguish in these early days. The baby girl-his child-was so sweet, and had so won Anna’s heart, since she was all that was left to her, that Anna rarely thought of her son.

The desire for life, waxing stronger with recovered health, was so intense, and the conditions of life were so new and pleasant, that Anna felt unpardonably happy. The more she got to know Vronsky, the more she loved him. She loved him for himself, and for his love for her. Her complete ownership of him was a continual joy to her. His presence was always sweet to her. All the traits of his character, which she learned to know better and better, were unutterably dear to her. His appearance, changed by his civilian dress, was as fascinating to her as though she were some young girl in love. In everything he said, thought, and did, she saw something particularly noble and elevated; she cherished a childish vision of Vronsky and Lupo as of a paladin and his steed. Her adoration of him alarmed her indeed; she sought and could not find in him anything not fine. She dared not show him her sense of her own insignificance beside him. It seemed to her that, knowing this, he might sooner cease to love her; and she dreaded nothing now so much as losing his love, though she had no grounds for fearing it. But she could not help being grateful to him for his attitude toward her, and showing that she appreciated it. He, who had in her opinion such a marked aptitude for a regimental career, in which he would have been certain to play a leading part-he had sacrificed his ambition for her sake, and never betrayed the slightest regret. He was more lovingly respectful to her than ever, and the constant care that she should not feel the awkwardness of her position never deserted him for a single instant. He, so manly a man, never opposed her, had indeed, with her, no will of his own, and was anxious, it seemed, for nothing but to anticipate her wishes. And she could not but appreciate this, even though the very intensity of his solicitude for her, the atmosphere of care with which he surrounded her, sometimes weighed upon her.

Vronsky, meanwhile, in spite of the complete realization of what he had so long desired, was not perfectly happy. He soon felt that the realization of his desires gave him no more than a grain of sand out of the mountain of happiness he had expected. It showed him the mistake men make in picturing to themselves happiness as the realization of their desires. For a time after joining his life to hers, after unwinding the hot-whip from his thigh and donning civilian dress, he had felt all the delight of freedom in general of which he had known nothing before, and of freedom in his love-and he was content, but not for long. He was soon aware that there was springing up in his heart a desire for desires-ennui. He longed for the camaraderie of the battlefield, missed the sparks and the heat and fog of combat, missed the clang of the Exterior door swinging shut behind him, missed the weight of a smoker in his hand. Without conscious intention he began to clutch at every passing caprice, taking it for a desire and an object. Sixteen hours of the day must be occupied in some way, since they were living in complete freedom, outside the conditions of social life that filled up time in Petersburg. As for the amusements of bachelor existence, which had provided Vronsky with entertainment on previous extra-atmospheric sojourns, they could not be thought of, since his sole attempt of that sort had led to a sudden attack of depression in Anna, quite out of proportion with the cause-a late game of lunar croquet with bachelor friends.

Relations with the society of the place-foreign and Russian-were equally out of the question owing to the irregularity of their position. The inspection of the various panoramas, of Earth’s blue-green magnificence or the starry sprawl of distant galaxies, had not for Vronsky, a Russian and a sensible man, the immense significance Englishmen are able to attach to that pursuit.

And just as the hungry stomach eagerly accepts every object it can get, hoping to find nourishment in it, Vronsky quite unconsciously clutched first at politics, then at new books, and then at pictures. He began to understand the semi-mystical art of painting with groznium-based pigments, how the artist could push the little pools of color around the canvas with subtle flicks of the brush, how the individual droplets would attract each other, creating luminous patterns as singular as fingerprints or snowflakes. Vronsky concentrated on these studies; with this technique he began to paint Anna’s portrait in her boots and helmet, and the portrait seemed to him, and to everyone who saw it, extremely successful.

CHAPTER 6

THE OLD, NEGLECTED MODULE they had leased, with its lofty, hard-textile ceilings and off-white, dimly lit passageways, with its slow-sequencing, Earth-scenery monitor frames, its manual door locks and gloomy reception rooms-this base did much, by its very appearance after they had moved into it, to confirm in Vronsky the agreeable illusion that he was not so much a Russian country gentleman, a retired army officer, as an enlightened, bohemian “moon man” and patron of the arts, who had renounced his past, his connections, and his planet for the sake of the woman he loved.

“Here we live, and know nothing of what’s going on,” Vronsky said to Golenishtchev as he came to see him one morning. “Have you seen Mihailov’s picture?” he said, pointing to Lupo’s monitor, where was displayed a communiqué from a Russian friend that he had received that morning, and pointing to an article on a Russian artist living in the very same colony and just finishing a picture which had long been talked about. “Couldn’t we ask him to paint a portrait of Anna Arkadyevna?” said Vronsky.

“Why mine?” Anna interjected. “After yours I don’t want another portrait. Better have one of Annie” (so she called her baby girl). She glanced with a smile through the glass porthole into the nursery, where the child was giggling delightedly at the clownish tumbling of a I/HurdlyGurdly/2.

“I have met Mihailov, you know,” Golenishtchev said. “But he’s a queer fish. He did not migrate to the moon entirely of his own volition, if my meaning is quite clear.” It was not, of course, and in answer to Vronsky’s curious expression Golenishtchev leaned forward, in exactly that conspiratorial fashion with which people in possession of secrets signal that they wish to be pressured into revealing them.

“I understand that many years ago he professed rather an extreme view on the Robot Question. Took the line that the extent of evolution of any given machine should be up to its owner, and its owner alone.”

“Yes, well,” Anna began, gesturing proudly to her own beloved-companion, preparing to defend that position, or at least argue its merits.

“But this Mihailov took the idea to a rather bizarre conclusion, publishing his opinion that robots were, in many ways, the equals of human beings-and that junkering a Class III was therefore tantamount to murdering a human being.” Vronsky raised his eyebrows, and Golenishtchev went on. “It is even said that he put these rather extreme opinions into practice, and…,” Golenishtchev made a pretense of blushing before continuing, “and fell in love with his wife’s Class III, and would have married it. The point is, one way or another he found it necessary to decamp for the charming lunar colony where now we find him.”

Golenishtchev settled happily back into his chair, evidently quite pleased with his own skills as raconteur, while Anna sat silent, absently stroking Android Karenina’s hand. Were Mihailov’s views so wrong? Was not her beloved-companion twice the woman-twice the person-twice the… whatever one might call it-than most of the people Anna had known?

“I tell you what,” said Anna finally. “Let’s go and see him!”

CHAPTER 7

THE ARTIST MIHAILOV was, as always, at work when the greeting signal of Count Vronsky and Golenishtchev sounded in his studio. He walked rapidly to the door, and in spite of his annoyance at the interruption, he was struck by the soft light that Android Karenina was shedding on Anna’s figure as she stood in the shade of the entrance listening to Golenishtchev, who was eagerly telling her something, while she evidently wanted to look round at the artist and his work.

They spoke but Mihailov only noticed every fifth word; he was examining in his mind’s eye that subtle nimbus of luminescence the robot imparted to her mistress. So he readily agreed to paint a portrait of Anna, and on the day he fixed, he came and began the work.

In another man’s house, and especially in Vronsky’s module, Mihailov was quite a different man from what he was in his studio. He behaved with hostile courtesy, as though he were afraid of coming closer to people he did not respect. He called Vronsky “Your Excellency,” and notwithstanding Anna’s and Vronsky’s invitations, he would never stay for dinner, nor come except for the sittings. Anna was even more friendly to him than to other people, and was very grateful for her portrait. Vronsky was more than cordial with him, and was obviously interested to know the artist’s opinion of his picture. Mihailov met Vronsky’s talk about his painting with stubborn silence, and he was as stubbornly silent when he was shown Vronsky’s picture. He was unmistakably bored by Golenishtchev’s transparent attempts to goad him into conversation on the Robot Question, and he did not attempt to oppose him.

From the fifth sitting the portrait impressed everyone, especially Vronsky, not only by its resemblance, but by its characteristic beauty. It was strange how Mihailov could have discovered just her characteristic beauty. “One needs to know and love her as I have loved her to discover the very sweetest expression of her soul,” Vronsky murmured to Lupo, who rumbled softly in his lap; though in truth it was only from this portrait that he had himself learned this sweetest expression of her soul. But the expression was so true that he, and others too, fancied they had long known it.

To Anna, what was remarkable was Mihailov’s decision to include Android Karenina in the painting, a decision not in keeping with traditions of portraiture, but one which seemed to her entirely fitting and appropriate.

On the sixth day of the sitting Golenishtchev entered with his usual bluster. As he pulled off his thick, dust-caked moon boots, he reported on a communiqué he had just received from a friend in Petersburg, who spoke of a rather bizarre new dictate emerging from the Ministry: all Class III robots, it seemed, were being gathered up by the government for some sort of mandatory circuitry adjustment.

Golenishtchev passed easily on to other subjects, nattering next about a funny little Moonie he had lost in the pit earlier today, and the various difficulties attending to Extractor maintenance in low gravity. But Mihailov and Anna Karenina-that is, the painter and the painted-seemed deeply struck by the pitman’s information. Mihailov laid down his brush and looked off through the big bay window of the module.

As for Anna, she instantly knew who was behind this enigmatic new Ministry program. “Might it be,” she murmured to Android Karenina, rising from her model’s stool, stretching, and walking arm and arm with her beloved-companion through the atelier, “that in my absence, whatever strange force lives inside my husband has gathered strength? Has my departure, my immersion in the freedom that the moon has given me, doomed my fellow Russians, and their beloved-companions, to suffer in my stead?”

And her heart was rent by feelings of guilt and frustration.

Vronsky did not share these concerns; he was instead agonized by his dawning understanding of his own failure to master the technique of groznium-pigment painting, and his realization that he never would. “I have been struggling on for ever so long without doing anything,” he said of his own portrait of her, “and he just looked and painted it. That’s where technique comes in.”

“That will come,” was the consoling reassurance given him by Golenishtchev, in whose view Vronsky had both talent and what was most important, culture, giving him a wider outlook on art. Golenishtchev’s faith in Vronsky’s talent was propped up by his need of Vronsky’s sympathy and approval for his own hope of finding groznium on the moon, and he felt that the praise and support must be mutual. “Isn’t that correct, M. Mihailov?”

But Mihailov remained silent. He walked, slowly, still clutching his brush, away from that big bay window and toward the airlock. “Tell me, sir,” he said to Golenishtchev, propping himself up against the reinforced steel of the door. “This Project; they intend to ‘gather up’ all Class Ills for what purpose?”

“It is not said-only that we must put our trust in the Ministry.”

“Ah,” he said. “I suppose we must do that. That I suppose we must do.”

A long stillness then filled the atelier: Golenishtchev looked toward Vronsky and Anna with raised eyebrows and a wry expression, impressing upon them his enjoyment of the idiosyncratic behavior of the great artiste. Vronsky continued his contemplation of the master’s portrait of Anna, while Anna herself stood with her hand in the gentle end-effector of Android Karenina, gazing down thoughtfully toward that big blue-green Class I toy, the Earth.

The airlock had already swung closed behind Mihailov, decisively clanking shut before anyone realized that he had exited-and had not taken with him his oxygen tank, nor even his helmet.

They watched with eyes wide with amazement, as the old painter tromped in his moon boots across the dusty lunar landscape and, showing no sign of the desperate constriction of his lungs that was surely taking place, blew a single, sad kiss in the direction of Earth; and then lay down heavily on the lunar dust, and ran out of breath.

After the strange death of Mihailov, Anna and Vronsky’s rented module suddenly seemed so obtrusively old and dirty: the periodic small malfunctioning of their Class I door locks, the streaks in the glass, the dried-out putty on the seals became so disagreeably obvious, as did the everlasting sameness of Golenishtchev, forever talking of the great day when he would strike his long-dreamed-of lunar ore. They had to make some change, and they resolved to return to Russia. In Petersburg Vronsky intended to arrange a partition of land with his brother, while Anna intended, somehow, to see her son.

Vronsky and Anna soon were climbing inside the ballistic canister and hurtling back toward the planet from whence they had come.

CHAPTER 8

LEVIN HAD BEEN MARRIED three months. He was happy, but not at all in the way he had expected to be. At every step he found his former dreams disappointed, and new, unexpected surprises of happiness. He was happy; but on entering upon family life he saw at every step that it was utterly different from what he had imagined. At every step he experienced what a man would experience who, after admiring the smooth, happy course of a meteor around a planetoid, should be given an opportunity to climb aboard that meteor. He saw that it was not all sitting still, floating smoothly; that one had to think too, not for an instant forgetting where one was floating; and that there was atmospheric pressure around one, and that one must endeavor somehow to steer one’s meteor; and that his unaccustomed hands would be sore; and that it was only to look at it that was easy; but that doing it, though very delightful, was very difficult, and very likely fatal.

As a bachelor, when he had watched other people’s married life, seen the petty cares, the squabbles, the jealousy, he had only smiled contemptuously in his heart. In his future married life there could be, he was convinced, nothing of that sort; even the external forms, indeed, he fancied, must be utterly unlike the life of others in everything. And all of a sudden, instead of his life with his wife being made on an individual pattern, it was, on the contrary, entirely made up of the pettiest details, which he had so despised before, but which now, by no will of his own, had gained an extraordinary importance that could not be denied. Although Levin believed himself to have the most exact conceptions of domestic life, unconsciously, like all men, he pictured domestic life as the happiest enjoyment of love, with nothing to hinder and no petty cares to distract. He ought, as he conceived the position, to do his work, and to find repose from it in the happiness of love. She ought to be beloved, and nothing more. But, like all men, he forgot that she too would want work. And he was surprised that she, his poetic, exquisite Kitty, could not merely busy herself about the Class Is and the furniture, about mattresses for visitors, about a tray, about the II/Cook/6 and the dinner, and so on.

Now her trivial cares and anxieties jarred upon him several times. But he saw that this was essential for her. And, loving her as he did, though he jeered at these domestic pursuits, he could not help admiring them. He jeered at the way in which she arranged the furniture they had brought from Moscow; rearranged their room; placed the Galena Box carefully on a certain shelf, then the next day reconsidered and moved it to another shelf; saw after a Surcease nook for the new II/Maid/467, a wedding gift from Levin’s parents; ordered dinner of the old II/Cook/6; came into collision with his ancient mécanicienne, Agafea Mihalovna, taking from her the charge of the Is and IIs.

He did not know the great sense of change Kitty was experiencing; she, who at home had sometimes wanted some favorite dish, or sweets, without the possibility of getting either, now could order what she liked, riding on a tandem I/Bicycle/44 with her darling Tatiana to the store to buy pounds of sweets, spend as much money as she liked, and order any puddings she pleased.

This care for domestic details in Kitty, so opposed to Levin’s ideal of exalted happiness, was at first one of the disappointments; and this sweet care of her household, the aim of which he did not understand, but could not help loving, was one of the new happy surprises.

Another disappointment and happy surprise came in their quarrels. Levin could never have conceived that between him and his wife any relations could arise other than tender, respectful, and loving ones, and all at once in the very early days they quarreled, so that she said he did not care for her, that he cared for no one but himself, burst into tears, and wrung her arms.

This first quarrel arose from Levin’s having gone with Socrates to a nearby farmhouse, having heard from a fellow landowner that another of the mysterious, gigantic, wormlike koschei had been spotted in that corner of the countryside. Going to investigate, Levin did not find the beast-machine itself, but paused for some time to contemplate what he found instead: a thick pool of expectorated ochre-yellow goo, along with the skeleton of a man with all the flesh neatly stripped off the bone.

He and Socrates passed a happy hour recreating the struggle, carefully measuring each scuff mark in the soil with a precision triangulator from the Class Ill’s beard. Ultimately they determined that this mechanical monster had to have been larger by a third than the one they had fended off, with the help of Grisha’s I/Flashpop/4, the previous season.

Socrates ran his usual analysis, but to Levin the only conclusion possible was that these UnConSciya koschei (were they UnConSciya?) were growing-but why? And how?

Flush with the usual pleasure he took in scientific investigation and discovery, Levin started off toward home; but as they drove, one happiness shifted to another, and soon his thoughts turned to Kitty, to her love, to his own happiness. The nearer he drew to home, the warmer was his tenderness for her. He ran into the room with the same feeling, with an even stronger feeling than he had had when he reached the Shcherbatskys’ house to make his offer. And suddenly he was met by a lowering expression he had never seen in her. He would have kissed her; she pushed him away.

“What is it?”

“You’ve been enjoying yourself,” she began, and he saw Tatiana standing behind her, glowing an accusatory cadmium yellow, her slender arms crossed. Kitty tried to be calm and spiteful, but as soon as she opened her mouth, a stream of reproach, of senseless jealousy, of all that had been torturing her during that half hour which she had spent sitting motionless at the window, burst from her. He felt now that he was not simply close to her, but that he did not know where he ended and she began. He felt this from the agonizing sensation of division that he experienced at that instant. He was offended for the first instant. “Enjoying myself!” he exclaimed. “I have literally been crouched in goo-thickened mud, examining mutilated human remains!”

“It’s true, Madame,” Socrates added, presenting as evidence a handful of the thick, yellow gunk, which dropped grossly through his endeffectors. Kitty and Tatiana drew back in disgusted unison from this repulsive offering.

Levin felt that he could not be offended by his dear Kitty, that she was himself. He felt as a man feels when, having suddenly received a violent blow from behind, he turns round, angry and eager to avenge himself, to look for his antagonist, and finds that it is he himself who has accidentally struck himself, that there is no one to be angry with, and that he must put up with and try to soothe the pain.

Before he could conceive of how to do so, the scene of marital discord was interrupted by the mechanized tritone of the I/Doorchime/3. A moment later the II/Footman/C(c)43 led in a handsomely uniformed pair of visitors, each with a rosy-fresh complexion, a neat, blond haircut and trim mustache, and slim black boots: Toy Soldiers.

“Good afternoon,” said the first of the men, speaking with every drop of the great respect and politeness due the master of Pokrovskoe and his new bride. The other man stood with arms crossed and his hat at a slightly insouciant angle on his blond head, saying nothing, a smile frozen on his face. His careful gaze was locked on Socrates and Tatiana.

“We are representatives of the Ministry of Robotics and State Administration,” continued the first man, speaking in a polished but rushed manner, as if from a prepared text. “We have come today to collect your Class III companion robots, in compliance with the nationwide order for compulsory circuitry adjustment. You were each granted an extension in respect of your nuptials. And may we add our congratulations, on behalf of the Ministry, on that blessed event.”

The other soldier uncrossed his arms and spoke curtly, gesturing roughly at the two companion robots. “These are the machines to be taken?”

Tatiana took a sidelong, slippered step toward Kitty, and the two locked arms and stood upright, like dancers preparing to launch into a partnered minuet.

“But no!” Kitty announced suddenly, with a wide-eyed, innocent expression. “They cannot go!”

Levin drew breath to speak, intending to upbraid his wife for indulging in such childish defiance of authority. Gazing upon her, however, arm in arm with her beloved-companion, he was softened by the distress evident on her face. What is more, he felt in his heart-especially when his intelligent eyes saw the concern evident in the flickering eyebank and nervous twitching of his own loyal Class III-that Kitty was absolutely correct in her defiance.

For how could they?

“Gentlemen, I beg that you pardon my wife the rashness of her young age and tenderhearted spirit. Naturally we shall comply and submit these machines for the necessary adjustments. But I wonder if you, in your official capacity, might first perform a service for a local landowner.”

Speaking rapidly, directing his words primarily to the first Toy Soldier, the one who seemed to him to have the friendliest nature, Levin explained what he and Socrates had observed at the old farmhouse: the skeleton stripped of flesh; the signs of struggle; the puddle of viscous ochre goo. He told them, too, of his own encounter with the gigantic, wormlike koschei outside Ergushovo. “Could you not, as long as your official business has brought you to this province, ride out to these spots I have mentioned and investigate? The threat of such unusual and deadly monsters is a cause of deep distress, as you can imagine, to myself and my household.”

But the Toy Soldier to whom Levin directed his appeal scratched his head and squinted, seemingly entirely uninterested in the bizarre creatures Levin spoke of. “That is indeed a most alarming tale,” he said softly, “but it does not, alas, have to do with us and our business.” Levin glanced from the corner of his eye at Socrates, and saw that he had brought one end-effector up to gently touch Tatiana where her torso unit met her lower portion-a touchingly human gesture. “Sir, we have precise instructions from the Ministry.”

Levin was inwardly cursing the seeming singlemindedness of the soldiers when the other one, who had been standing mute with arms crossed, seeming not to pay attention, held up an open palm. “This wormlike machine,” he said, “did it emit a sound-like a sort of ticking, a tikka tikka tikka sound?”

Levin nodded his assent, at which the Toy Soldier sighed and spoke in a whisper to his companion. As they turned on their slim black boots and walked back toward the door, the first of the soldiers glanced amiably over his shoulder at Levin, and said in a casual tone, “We shall return shortly, and complete our previously announced business here. We have no desire to perform our commission by force.”

“No,” said the second soldier, as he pulled the big front door of the manor house behind them. “Not yet.”

Kitty burst into tears, running to her Class III and hiding her face in Tatiana’s thin metal bosom. “I could not bear for her to be taken!” she said through her tears.

“Nor I, my dear,” was Levin’s reply, as he looked gravely out the front window, watching the Toy Soldiers ride off. “Nor I.”

“And what will they do with them? I mean, really do?”

“I don’t know, Kitty.”

“Madame?” interjected Tatiana anxiously, as Levin and Kitty embraced.

“Sir?” echoed Socrates.

“Yes, yes, beloved-companions,” Levin said. “You are quite right. Now we must leave Pokrovskoe. And fast.”

CHAPTER 9

IMMEDIATELY THERE COMMENCED in the Levin household that frenzy of activity, among robots and humans alike, attendant upon a rapid and secret flight to safety. What to take? How much luggage? How best to travel undetected? And where to go?

“I shall take the Class Ills with me to the small provincial town of Urgensky, where my brother Nikolai is residing,” Levin said. “In his last communiqué he said his own Class III, Karnak, has not been taken in for adjustment. We may hope that Urgensky is too out of the way, with too few Class III companion robots in residence there, to be considered worth the effort of the state to collect them.”

Kitty’s face changed at once.

“When?” she said.

“Immediately! A visit to my ailing brother is a perfectly reasonable excuse for travel, and I shall carry the Surceased robots with my luggage.”

“And I will go with you, can I?” Kitty said.

“Kitty! What are you thinking of?” he said reproachfully.

“How do you mean?” she said, offended that he should seem to take her suggestion unwillingly and with vexation. “Why shouldn’t I go? I shan’t be in your way. I-”

“The journey is to be long, and likely dangerous,” said Levin, all the fire of their earlier quarrel returning. “Why should you-”

“Why? For the same reason as you.”

“Ah!” said Levin, and bitterly muttered to Socrates, though loud enough for Kitty to hear. “At a moment of such gravity, she only thinks of her being dull by herself, alone here in the pit-house without me or Tatiana.”

“Now now,” counseled Socrates, looking guiltily at Kitty. “Do not be cross with her.”

“No!” said Levin sternly. “It’s out of the question.”

Tatiana brought Kitty a cup of tea from the I/Samovar/1(8); Kitty did not even notice her. The tone in which her husband had said the last words wounded her, especially because he evidently did not believe what she had said.

“I tell you, that if you go, I shall come with you; I shall certainly come,” she said hastily and wrathfully.

“It is out of the question!”

“Why out of the question? Why do you say it’s out of the question?”

“Because I’ll be going God knows where, by all sorts of roads and to all sorts of hotels. And my brother lives in entirely unsuitable circumstances! That would be reason enough to bar your coming, before one even considers the danger of our being discovered by agents of the Ministry and prosecuted as Januses for disobeying the compulsory adjustment order. You would be a hindrance to me,” said Levin, trying to be cool.

“What dangers you can face, I can!” replied Kitty hotly.

“Yes, yes. But think, too, of where we are going, and whom we will meet. For one thing then, this woman’s there whom you can’t meet.”

“I don’t know and don’t care to know who’s there and what. My husband is undertaking a risk, to protect his beloved-companion as well as mine, and I will go with my husband too…”

“Kitty! Don’t get angry. But just think a little: this is a matter of such importance that I can’t bear to think that you should bring in a feeling of weakness, of dislike to being left alone. Come, you’ll be dull alone, so go and stay at Moscow a little.”

“There, you always ascribe base, vile motives to me,” she said with tears of wounded pride and fury. “I didn’t mean, it wasn’t weakness, it wasn’t… I feel that it’s my duty to be with my husband when he’s in trouble, but you try on purpose to hurt me, you try on purpose not to understand…”

“No, this is awful! To be such a slave!” cried Levin, getting up, and unable to restrain his anger any longer. But at the same second he felt that he was beating himself.

“Then why did you marry? You could have been free. Why did you, if you regret it?”

He began to speak, trying to find words not to dissuade but simply to soothe her. But she did not heed him, and would not agree to anything. He bent down to her and took her hand, which resisted him. He kissed her hand, kissed her hair, kissed her hand again-still she was silent. But when he took her face in both his hands and said “Kitty!” she suddenly recovered herself, and began to cry, and they were reconciled.

It was decided that they should go together, as soon as possible. The robots were put in Surcease, and locked together in a trunk.

CHAPTER 10

THE HOTEL IN URGENSKY, the provincial town where Nikolai Levin was living, was one of those provincial hotels which are constructed on the newest model of modern improvements, with the best intentions of cleanliness, comfort, and even elegance, but owing to the public that patronizes them, are with astounding rapidity transformed into filthy taverns with a pretension of modern improvement that only makes them worse than the old-fashioned, honestly filthy hotels.

There remained only one filthy room, which would barely fit the two of them, and their robots, once revivified. Levin was feeling angry with his wife because what he had expected had come to pass: at the moment of arrival, when his heart throbbed with emotion and anxiety to find his brother and make whatever arrangements were necessary to find a place where the Class Ills could stay here undetected, he had to be seeing after her.

“Go, do go!” she said, looking at him with timid and guilty eyes.

He went out of the door without a word, and at once stumbled over his brother’s consort, Marya Nikolaevna, who had heard of his arrival and had not dared to go in to see him. She was just the same as when he saw her in Moscow; the same woolen gown, and bare arms and neck, and the same good-naturedly stupid, pockmarked face, only a little plumper.

Speaking rapidly and with obvious apprehension, Marya Nikolaevna expressed her relief at seeing him: Nikolai’s illness, she explained, had dramatically worsened, and indeed she feared he was now at death’s door.

“What? Well, and how is he at present?”

“Very bad. He can’t get up. His body writhes with pain, and there is in the texture of his flesh a strange and unseemly rippling. I fear the worst. Come,” Marya Nikolaevna continued. “He has kept expecting you.”

The door of his room opened and Kitty peeped out. Tatiana’s head peeped out just under hers. Levin crimsoned both from shame and anger with his wife, who had put herself and him in such a difficult position; but Marya Nikolaevna crimsoned still more. She positively shrank and flushed to the point of tears, and clutching the ends of her apron in both hands, twisted them in her red fingers without knowing what to say or what to do.

For the first instant Levin saw an expression of eager curiosity in the eyes with which Kitty looked at this awful woman, so incomprehensible to her; but it lasted only a single instant.

“Well! Have you explained to her our plan, regarding the Class III robots?” she turned to her husband and then to her.

“But one can’t go on talking in the corridor like this!” Levin said, looking angrily at a gentleman who walked jauntily at that instant across the corridor, as though going about his affairs. Could this be one of them? A Toy Soldier? Some other agent of the state, disguised in everyday clothes?

“Well then, come in,” said Kitty, turning to Marya Nikolaevna, who had recovered herself, but noticing her husband’s face of dismay, she added, “or go on; go, and then come for me,” and she and Tatiana went back into the room.

Levin went to his brother’s room. There he was aghast to see the instructions etched above the door, but he obeyed them nonetheless, donning the elaborate sickroom costume of mask, gown, and gloves.

“My poor brother,” he murmured to Socrates, who was donning his own mask; of course a companion robot required no protection from human infection, but the costume would at least delay his immediate detection as a machine-man, should a doctor or other stranger happen into the room.

Levin, from Marya’s descriptions, had expected to find the physical signs of the approach of death more marked-greater weakness, greater emaciation, but still almost the same condition of things. He had expected himself to feel the same distress at the loss of the brother he loved and the same horror in face of death as he had felt then, only in a greater degree.

In this little, dirty room with the caution posted by the door, with the painted panels of its walls filthy with spittle, and conversation audible through the thin partition from the next room, in a stifling atmosphere saturated with impurities, on a bedstead moved away from the wall, there lay, covered with a quilt, a body. One arm of this body was above the quilt, and the wrist, huge as a rake handle, was attached, inconceivably it seemed, to the thin, long bone of the arm, smooth from the beginning to the middle. The head lay sideways on the pillow. Levin could see the scanty locks wet with sweat on the temples and the tense, transparent-looking forehead.

Propped against the opposite wall was Karnak, Nikolai’s staggering rust-bucket of a Class III, if anything more decrepit and dilapidated than the last time Levin had seen him. “One can see why the Ministry has no interest in adjusting such machines,” whispered Levin to Socrates, who had instinctively recoiled from the sad, shrunken metal figure.

As they approached the bed, any doubt that this wracked figure was Levin’s dear brother became impossible. In spite of the terrible change in the face, Levin had only to glance at those eager eyes raised at his approach, only to catch the faint movement of the mouth under the sticky mustache, to realize the terrible truth that this death-like body was his living brother.

When Konstantin took him by the hand, the thick, white protective gloves feeling scarcely protection enough, Nikolai smiled. There was at that moment the scrape of a boot heel in the hallway outside, and Levin looked up sharply: was it them? Had they been found already? Socrates pulled his mask higher over his face, his eyebank flashing unsteadily.

“You did not expect to find me like this,” Nikolai articulated with effort.

“Yes… no,” said Levin. The sound of the footsteps faded down the hallway.

A great swell of flesh bubbled up from Nikolai’s midsection, as if his body was a balloon and air had been temporarily forced into one part of it. Levin looked away, as Nikolai winced and groaned.

“How was it you didn’t let me know before that you were suffering so?”

Nikolai could not answer; again the flesh of his torso bubbled grotesquely, and again he gritted his teeth and scowled with evident agony.

Levin had to talk so as not to be silent, and he did not know what to say, especially as his brother made no reply. His odd condition was not, it appeared, contained to his midsection; as Levin watched, one of Nikolai’s eyes bulged grotesquely, and then the other. He tried to speak and his swollen tongue lolled like bread dough onto his cheek. Containing his horror and revulsion, Levin said to his brother that his wife had come with him. When his tongue detumesced and he could speak again, Nikolai expressed pleasure, but said he was afraid of frightening her by his condition. A silence followed-Levin would not say so, but he had precisely the same fear.

“Let me explain the reason we have come,” Levin then said. “It has to do with…” He lowered his voice to a whisper, drawing nearer his brother’s wrecked flesh, and said, “the robots.”

Karnak’s leg fell off, and he fell to the ground with a scrape and clank. Socrates, politely, lifted the other machine back up and placed him in his previous position against the wall.

Suddenly Nikolai stirred, and began to say something, entirely ignoring Levin’s whispered comment about the Class Ills and speaking instead of his health. He found fault with the doctor, regretting he had not a celebrated Moscow doctor with a II/Prognosis/4 or higher. Levin saw that he still hoped.

Seizing the first moment of silence, Levin got up, anxious to escape, if only for an instant, from his agonizing emotion, and said that he would go and fetch his wife.

“Very well, and I’ll tell Karnak to tidy up here. It’s dirty and stinking here, I expect. Karnak! Clear up the room,” the sick man said with effort. Karnak swiveled his head unit uncertainly, his aural sensors detecting some distant sensory input.

“Well, how is he?” Kitty asked with a frightened face when Levin went to fetch her.

“Oh, it’s awful, it’s awful! What did you come for?” said Levin.

Kitty was silent for a few seconds, looking timidly and ruefully at her husband; then she went up and took him by the elbow with both hands.

“Kostya! Take me to him; it will be easier for us to bear it together. You only take me, take me to him, please, and go away,” she said. “You must understand that for me to see you, and not to see him, is far more painful. There I might be a help to you and to him. Please, let me!” she besought her husband, as though the happiness of her life depended on it.

Levin was obliged to agree, and regaining his composure, and completely forgetting about Marya Nikolaevna by now, he went again to his brother with Kitty.

Stepping lightly, and continually glancing at her husband, showing him a valorous and sympathetic face, Kitty donned the mask and gloves and gown, went into the sickroom, and, turning without haste, noiselessly closed the door. With inaudible steps she went quickly to the sick man’s bedside, and going up so that he had not to turn his head, she immediately clasped in her fresh, young, thickly gloved hand, the skeleton of his huge hand, pressed it, and began speaking with that soft eagerness, sympathetic and not jarring, which is peculiar to women.

“We have met, though we were not acquainted, on the Venus orbiter,” she said. “You never thought I was to be your sister?”

“Would you have recognized me?” he said, with a radiant smile at her entrance.

“Yes, I would. I am sorry to have found you unwell, and I hope I can be of some use to you.”

“And I to you, and to your machines.” Nikolai smiled, and from this quiet statement Levin gathered that his brother had indeed heard his allusion to the robots, and was willing despite his grave health to help keep their beloved-companions safe.

It was decided that when the time came for Levin and Kitty to return to Pokrovskoe (meaning, though none spoke the words aloud, when Nikolai had passed into the Beyond), their Class Ills would stay here, their exterior trim radically downgraded, masquerading as Class IIs at work in a local cigarette factory-the owner of which, Nikolai felt sure, would accept a small payment to hide the robots among his workforce-and spending their Surceased nights in the dingy factory basement.

CHAPTER 11

AS THE HOURS and then days passed, Levin found he could not look calmly at his brother; he could not himself be natural and calm in his presence. When he went in to be with the sick man, his eyes and his attention were unconsciously dimmed, and he did not see or distinguish the details of his brother’s position. He smelled the awful odor, saw the dirt, disorder, and miserable condition, and heard the groans, and felt that nothing could be done to help. While Kitty directed her full attention and sympathy to the dying man, and Socrates anxiously circumnavigated the room, Levin’s mind wandered, like a landowner traveling the acres of his life. He surveyed all that was pleasurable, like his pit-mining operation and his beloved Kitty, and he surveyed all those tracts causing him concern: the mysterious, wormlike mechanical monsters rampaging the countryside; the circuitry adjustment protocol, which seemed to Levin an inexplicable and unjustified exercise of state power against the citizenry; and worst of all, the unspeakable illness eating his dear brother alive.

It never entered his head to analyze the details of the sick man’s situation, to consider how that body was lying under the quilt, how those emaciated legs and thighs and spine were lying huddled up, how those long waves of undulating flesh were appearing and disappearing, and whether they could not be made more comfortable, whether anything could not be done to make things, if not better, at least less bad. It made his blood run cold when he began to think of all these details. He was absolutely convinced that nothing could be done to prolong his brother’s life or to relieve his suffering. To be in the sickroom was agony to Levin; not to be there still worse. And he was continually, on various pretexts, going out of the room and coming in again, because he was unable to remain alone.

But Kitty thought, and felt, and acted quite differently. On seeing the roiling flesh of the sick man, she pitied him. And pity in her womanly heart did not arouse at all that feeling of horror and loathing that it aroused in her husband, but a desire to act, to find out all the details of his state, and to remedy them. And since she had not the slightest doubt that it was her duty to help him, she had no doubt either that it was possible, and immediately set to work. The very details, the mere thought of which reduced her husband to terror, immediately engaged her attention. She sent for the doctor, and set Tatiana and Socrates and Marya Nikolaevna to sweep and dust and scrub, as slow, crossed-wire Karnak was quite useless in this regard. She herself washed up something, washed out something else, laid something under the quilt. Something was by her directions brought into the sickroom, something else was carried out. She herself went several times to her room, regardless of the men she met in the corridor, got out and brought in sheets, pillowcases, towels, and shirts.