PART TEN Global Governance: Who Would Our Bedfellows Be?

The oft-stated goal of global governance—one-world government—begs the question of whether such rule would be democratic and freedom loving or autocratic and arbitrary. Would the world government be fundamentally honest, albeit with a few bad apples, or would it be dominated by kleptocracies—governments whose rulers are only intent on stealing and plundering their way to mega-wealth? Would it be respectful of human rights or ride roughshod over them as happens in many parts of the world?

The fact is that the nations we would be entrusting with our sovereignty are not worthy of the trust. Were this a better world, filled with better nations and rulers, it would be different. But the world is crammed with tiny nations—barely as large as any of our states—who could easily gang up on us and become the tail that wags the dog. And far too many of the nations of the world—more, much more, than would be needed to outvote us—are autocratic, not free, corrupt, and regular violators of human rights.

It is one thing for those of us on the East Coast of the United States to trust our destiny to the voters of the West Coast or the South or the Midwest. It is quite another to give that power to Russia, China, or a collection of tiny, lightly populated, third world autocracies, riddled with corruption and dedicated to the enrichment of their leaders. These are not the kind of bedfellows we want in our government. They are not worthy of entrusting our sovereignty to them.

So let’s examine those who would come to rule us in any global governance scheme.

RULE OF THE LILLIPUTIANS: HOW TINY NATIONS OUTVOTE US

The fundamental concept underscoring global governance is the principle of one nation, one vote. All UN conferences and decision-making bodies—with the sole exception of the Security Council—operate on this principle. With 193 countries in the United Nations, a coalition of very small nations exercises a disproportionate power.

Is the principle of one nation, one vote an appropriate basis for global governance?

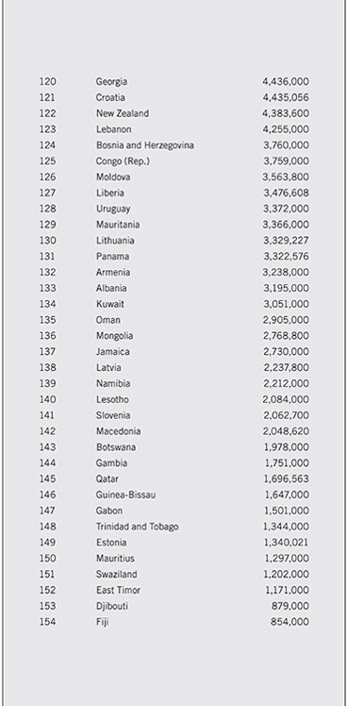

It takes 97 nations to constitute a majority of the 193 UN members. But it is possible that a majority of tiny nations could coalesce and outvote the rest. The 97 least-populated UN members have a combined census of only 241 million inhabitants—about one-quarter less than the population of the United States (310 million). These nations, representing only 241 million people, comprise less than 4 percent of the world’s 7 billion people, but together they can determine the direction of its decisions.

Many of these countries are really tiny, their nationhood a result of being an island or remote from population centers. Forty countries—enough to outvote the members of NATO—have populations of less than one million people and thirteen have fewer than one hundred thousand people. The most populated of the 97 smaller countries—which, again, can constitute a majority of voting members of the UN—is Bulgaria, with a population of just over 7 million. That’s smaller than the population of the five boroughs of New York City!

What kind of global government can be predicated on a system in which Monaco (33,000), San Marino (33,000), Palau (20,000), Tuvalu (20,000), and Nauru (10,000) can outvote China (1.3 billion), India (1.2 billion), and the United States (310 million)?

Permitting these minuscule countries to cast one vote each summons the memory of the old pocket boroughs that were represented by one member each in the British House of Commons for centuries. Wealthy landowners would get their own estate and the surrounding town—largely populated by their servants—declared a constituency and become entitled to their own personal member of Parliament. Apportionment of seats being what it was, these tiny districts would often outvote the big cities of the UK.

The US Supreme Court realized the injustice of apportioning power based on any measurement other than population when it struck down legislative districts at the state and local level where seats were not allocated based on the number of inhabitants. It was common practice in the state senates of forty-nine states (Nebraska is unicameral) to allocate seats by county, mirroring the composition of the US Senate, where each state gets two members. This distorted legislative apportionment permitted rural counties to outvote the big cities and perpetuate the power of the rural squires who dominated politics in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and many eastern states.

The system came to be derided as “one cow, one vote” and met its doom at the hands of the Supreme Court in the reapportionment cases of 1964. The justices ruled that both houses of the state legislatures must be apportioned based only on population. They distinguished state senates from the US Senate because the Constitution explicitly mandates two members from each state for the latter. This provision, of course, stems from the fact that the early United States was a federation of thirteen sovereign states that had won their independence from Great Britain.

It is not merely that it is unfair for St. Kitts and Nevis in the Caribbean and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific to have votes equal to that of the United States. It is that these tiny islands can have no conception of what things are like in larger countries. How can they cast intelligent votes based on their own life experiences living in nation-states that are really no larger than small towns?

And then there is the potential for corruption. Like the pocket boroughs of old Britain, these tiny countries frequently tend to be one-man, quasi-feudal estates. Their UN delegates vote the interests of the one person who controls the island—or the one company. And, in many cases, that vote can be easily bought by offers of foreign aid, investment, or access to the markets of larger nations.

The potential for corruption and injustice implicit in allowing the tail of 241 million people to wag the dog of 7 billion people in the world is too great to let the system continue.

Here’s a list of the 97 smallest nations in the UN who constitute a majority of the world body. These tiny nations can outvote the rest of the world and its 7 billion people.1

At its inception, the Charter for the United Nations carefully vested most of the organization’s power in a Security Council dominated by its five permanent members: the United States, Britain, France, Russia, and China, each of whom was given a veto power over the actions of the global body. This formulation stemmed from the fact that the UN was originally formed as an association of the Allied powers, who had emerged victorious from the Second World War. The vital role played by each nation was recognized in giving it the veto power.

The power of the Security Council overshadowed the rest of the UN organization during the Cold War since neither Russia nor the United States and our allies was willing to trust its fate to a roll of the dice in the General Assembly, where each nation has a single vote.

When North Korea, with Chinese help, invaded South Korea in 1949, the Soviet veto would have precluded intervention by the Security Council. The United States and our allies passed the “uniting for peace” resolution in the General Assembly, which became the basis for the UN’s intervention in Korea to repel communist aggression. Never again would Russia permit the General Assembly to play such a role.

As the decolonialization movement spread throughout Asia and Africa, membership in the United Nations expanded rapidly.

The original UN General Assembly had 51 members when the organization opened its doors in 1945. By 1959 it had grown to 82 members. The next year, 1960, it spurted in size to 99 as former colonies began to join in large numbers. By 1970 it stood at 127. By 1980 it was 154 and by 1990 the membership of the General Assembly was 159.

Then a second spurt in growth happened as the Soviet Russian and Yugoslav confederations broke apart. Membership soared to 189 in 2000. It now stands at 193.

With each new third world addition to the body, the voting power of the West—and Russia—was diluted and the power of the nations of Asia and Africa grew. A sharp anti-American bias became evident as the General Assembly increased in size.

For example, in 2007, on average, only 18 percent of the members of the General Assembly voted with the United States on any given vote (not counting unanimous votes). In 2008, the percentage was up to 26 percent. Then, under Obama, it rose to 42 percent as the administration moved closer to the opinions of the third world countries. (Some would say that it began to share their anti-American bias.) All told, the United States voted no in the General Assembly more often than any other UN member, even in the 2010 session.2

Yet it is this very body—the 193 members of the United Nations—and this very voting system—one nation, one vote—that we are about to vest with enormous power. If the globalists and their Obama administration allies have their way, these 193 nations will decide where we can drill for oil offshore, which sea-lanes shall be open for our navigation, how the global Internet is administered, how much we should pay to third world countries to adjust to climate change, what limits to place on our carbon emissions, and dozens of other topics now consigned to our national, state, and local jurisdictions.

In entering into governance by this worldwide body of 193 equal nations, we are dealing into a card game with a stacked deck. We cannot hope to win. We can’t even expect fairness.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War’s bipolarity, the power of the Security Council within the UN declined. Now its role is primarily limited to UN military intervention and economic sanctions to keep the peace and, supposedly, to fight aggression. But more and more power has flowed to the General Assembly, and the concept of one nation, one vote has become enshrined as the core principle of global governance.

The diminishing power of the major UN nations is evident in the increasing domination of the Group of 77, a coalition of the poorer nations determined to use the UN as a vehicle to channel money from developed nations to their own needs. Although these countries donate only 12 percent of the UN’s operating budget, their combined power has become dominant in the General Assembly.

For example, when the US ambassador to the UN under George W. Bush, John Bolton, pushed through a budget cap on UN spending, these seventy-seven nations, who paid about one-eighth of the cost of UN operations, vetoed the proposal. They saw nothing wrong with continued spiraling growth in spending. As long as they weren’t paying the bill.

And when it came to limiting investigations of corruption at the UN and defunding the agencies charged with exposing fraud, it was this same group of nations that leveraged the global body. Their brazen efforts to condone and even institutionalize graft and bribery are chronicled in our most recent book, Screwed!, in the chapter “The United Nations of Corruption.”

Before we dilute our national sovereignty, we are entitled to ask of our fellow nations, with whom we would share power in global governance, are they worthy countries. Are they free? Are they corrupt? Do they respect human rights? The short answer: No, they don’t.

ARE THEY FREE?

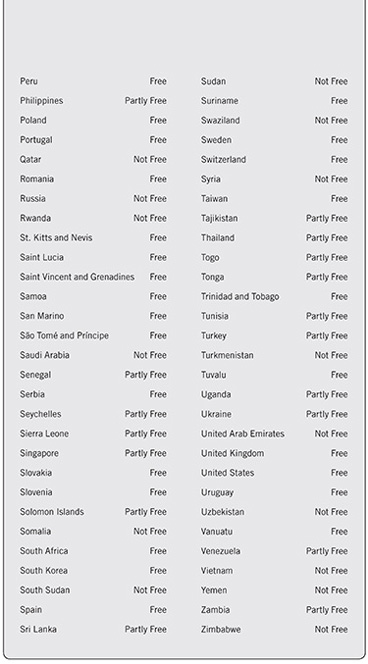

Freedom House, an organization founded in 1941, at the start of World War II, has kept meticulous and impartial track of the degree of freedom and democracy in each of the world’s nations. Every year, it publishes a widely respected report categorizing some nations as free, others as partially free, and still others as not free. Each year, nations move from one category to the other as their political institutions change, revolutions occur, and power changes hands by coups or elections.

Freedom House itself has a storied history. It was founded at the behest of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the aftermath of his reelection in 1940. Bipartisan, its first cochairs were First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and the Republican candidate for president FDR had just defeated, Wendell Willkie. Its original purpose was to encourage US intervention in World War II despite isolationist pressure to stay out. Since then, its designation of the degree of freedom in the world’s nations has been accepted almost universally (except, of course, by those whose lack of freedom it questions).

In 2011, Freedom House designated 87 of the world’s 195 nations (including two non-UN members) as “free.” Another 60 countries were “partially free.” The other 48 nations were labeled “not free.”3

Immediately, we see the defect of the one-nation, one-vote rule. The 87 free countries make up a minority of the total UN membership (45 percent).

The 45 percent of the nations that are free have great legitimacy. Their delegates come from democratically elected governments, chosen in free elections. When their delegates speak, they do so with the authority of a government that has been chosen by the consent of the governed.

But who do the delegates from the 55 percent of the world’s nations that are only partially free or not free at all represent? Why is it appropriate that they should each have a vote when they stand for nobody but themselves and their own dictatorial or autocratic rulers? Does the delegate from China, for example, speak for his 1.3 billion people or just for the handful that serve on the Communist Party’s ruling Politburo? Does Vladimir Putin represent the majority of the Russian people (who chose him in totally rigged, undemocratic elections where the results were intentionally miscounted)?

To lump the free and not-free countries into one world body and to assign each the same voting power mocks the very concept of democracy. The UN is very punctilious about preserving the idea of majority rule and its implication of democratic decision making in the General Assembly. But what kind of democracy is it when 55 percent of the delegates come from governments that do not represent the people who live there?

Even if we base representation on population, we don’t do much better in terms of freedom. According to Freedom House, 3 billion people, or 43 percent of the world’s population, live in free countries. Two and a half billion—or 35 percent—live in countries that are rated as not free (about half from China with its 1.3 billion people). The rest come from only partly free countries.

Freedom House is rather charitable in its designation “partly free.” It defines the category: “A Partly Free country is one in which there is limited respect for political rights and civil liberties. Partly Free states frequently suffer from an environment of corruption, weak rule of law, ethnic and religious strife, and a political landscape in which a single party enjoys dominance despite a certain degree of pluralism.”4

Freedom House, for example, labels as “partly free” the South American countries under the thumb of Hugo Chavez and his puppets—Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Nicaragua. Despite the fact that no elected president has served out his term without being toppled or assassinated, Pakistan is rated as partly free. Liberia, just recovering from the long dictatorship of Charles Taylor, enjoys the partly-free rating as well. The authoritarian, undemocratic regime in Singapore is also rated partly free.

It is no bargain to live in a partly free country.

So who are we about to surrender our sovereignty to? A world body dominated by small nations, barely the size of one of our states, in which we have only one of 193 votes, where the majority of the countries are not free to choose delegates who represent their own people?

There is nothing inherent in the idea of global governance that is wrong. Indeed, we are all human and we all inhabit the same planet so eventually some form of global government may be appropriate. But today, such a government could only be as strong and just as its component parts. The failure of freedom to spread to more than a minority of the world makes the submersion of our sovereignty into such a worldwide body an act that will lead to the surrender of our freedoms.

The very premise of the United Nations is based on the idea that you take the countries as you find them. Whether they are dictatorships, monarchies, or tyrannies of any description does not matter. As long as they are in de facto control of their populations and landmasses, they are nations entitled to representation and recognition. If the people want to change the government, that’s their business. If they want greater freedom, good luck to them. But, in the meantime, the UN takes all comers and does not have a litmus test for freedom.

The United Nations was set up to be a kind of permanent international conference, akin to the gatherings of the top world leaders that formulated policy for the Allies during World War II. Where Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt met at Yalta to design the postwar world, now their delegates meet at the United Nations to keep it going and to avert a catastrophic world conflict. That’s, of course, why the Security Council—which mimics their wartime conferences—had most of the power in the early days of the United Nations.

But as power shifted to the General Assembly, where each nation cast a vote and none had a veto, the UN’s refusal to distinguish between legitimate, democratic governments and autocratic ones becomes harder to justify. And when they meet not to negotiate, but to govern, they are not entitled to the same level of participation.

A value-free acceptance of all comers makes perfect sense in a negotiation where countries meet to discuss mutual problems or resolve conflicts. In those cases, the dictator who runs one country must sit down with the elected leader who rules the other nation on terms of parity and equality. What matters is control, not legitimacy.

If Saudi Arabia is controlled by a king, Russia by a dictator, China by a one-party system, that is none of our business in international negotiations. We have to take them as they are and negotiate to maintain harmony, trade, and peace.

But when the talk switches from horse-trading and negotiation to governance, the idea of including not free governments and according them a vote equal to that cast by free nations is not a wise idea. And to immerse ourselves in a global governing body where a majority of the votes are cast by peoples who are, to some degree or the other, enslaved, makes no sense at all. We must not subject ourselves to the rule of a world body dominated by autocrats.

Nor need we be Gulliver, the 310 million person democracy, being tied down by 97 Lilliputian nations each with populations of 7 million or less, together casting a majority of the votes and bending global policies to their own needs and outlooks.

We are, at least, entitled to a veto—as we have in the Security Council—and should make common government only with fellow democracies committed to human freedom and the consent of the governed.

In a world of nations a majority of whom are not free, there can be no government by consent of the governed and the United States of America should not be part of it.

ARE THEY HONEST?

But our likely new rulers in the third world are not only undemocratic and not free, they are also hopelessly corrupt. A new word had to be created to articulate the degree of corruption: kleptocracy (a government based on stealing and graft). These governments are to be distinguished from those in which scandal occasionally or even frequently rears its head. Every government has a few greedy public servants who help themselves to riches and wealth. But they are usually investigated and often punished. But kleptocracies are different. These are governments whose mission is to steal, whose reason for being is to make money for its leaders.

These states are more like criminal gangs than regular governments. Their ruling elites get to serve as presidents, prime ministers, ambassadors, negotiators, delegates, foreign secretaries, and cabinet secretaries. In each position, they are empowered to steal all they can and to share their loot with one another.

To such nations, membership in the United Nations affords entrée to a realm of vast resources there just for the taking. And take they do.

What proportion of the UN membership are kleptocracies?

Once again, we can turn to a reputable international civic group for the answer. Just as Freedom House compiles rankings of countries based on the degree of freedom their people enjoy, so Transparency International rates them based on their propensity toward corruption.

Transparency International defines corruption:

Corruption is the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. [The index] focuses on corruption in the public sector, or corruption which involves public officials, civil servants or politicians. The data sources used to compile the index include questions relating to the abuse of public power and focus on: bribery of public officials, kickbacks in public procurement, embezzlement of public funds, and on questions that probe the strength and effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts in the public sector.6

Their methodology is impressive.

• They take a survey of more than seventy thousand households in ninety countries to measure “perceptions and experiences of corruption.”7

• They interview business executives who export goods and services to learn “the perceived likelihood of their firms [having to] bribe” officials in each nation to whom they sell.8

• They issue a Global Corruption Report, which explores corruption in particular sectors or spheres of government operations.9

• Finally, they conduct a “series of in-country studies providing an extensive assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the key institutions that enable good governance and integrity in a country (the executive, legislature, judicial, and anti-corruption agencies among others).”10

Based on this extensive research, Transparency International rates every nation on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 meaning that it is highly corrupt and 10 meaning that it has quite high standards of honesty and integrity.

The results are dismal. Corruption is the order of the day in most countries of the world—the very nations that would rule any global government to which we assent!

About three-quarters of the countries of the world—132 of the 182 nations rated—received less than a 5 (on a 1–10 scale), indicating that they were badly corrupted. Ninety-two (half the countries) got a rating of 3 or less, indicating that corruption had penetrated to its very core. Only fifty of the 182 nations got better than a 5 on the corruption scale!

Here are the rankings for each country:11

Are these the nations to whom we are thinking of surrendering our sovereignty, giving them a one-nation, one-vote right to govern us and control our economies, the sea, the Internet, our industries, and many other key aspects of our lives?

But it is not just the member states of the UN that are hopelessly mired in corruption; it is the United Nations itself.

This institutional tolerance of corruption was much in evidence in the 1990s as the UN administered the Oil-for-Food program in Iraq. Established under UN auspices to channel revenues from Iraq’s carefully regulated sale of oil to provide food and medicine for its people, starving under the impact of international sanctions, the program became a poster child for corruption. The money mainly went into the pocket of the dictator, Saddam Hussein, and into those of the UN officials charged with administering the program.

The UN corruption demonstrated by the Oil-for-Food program is sickening. But worse—far worse—is the immunity and impunity of those who committed the larceny. They have not been punished or disciplined or even fired. They remain at their desks in the UN headquarters, anxious to see greater globalism enlarge their opportunities for personal enrichment and theft.

The oil-for-food program began in 1990 when the UN imposed economic sanctions against Saddam Hussein. To overturn the sanctions, Saddam worked to loosen the sanctions by pleading that they were starving his people and denying medical care to his children. So the UN decided to allow Saddam to sell limited amounts of oil to feed his people. As a result of his overt efforts to stir up sympathy for his starving people and his covert bribery of top UN officials, Saddam gradually expanded the amount of oil he could sell until the limits were ended entirely.

But the slush fund his oil profits generated found its way into the pockets of a plethora of international politicians often at the highest levels. The program included a 2.2 percent commission on each barrel of oil sold. Over the life of the oil-for-food program, the UN collected $1.9 billion in commissions on the sale of oil.12

The program was overseen by the Security Council of the UN, but subsequent investigations revealed that the leaders and UN delegates of three of the five permanent members—Russia, China, and France—were on the take, pocketing commissions as they rolled in.

• France received $4.4 billion in oil contracts.

• Russia received $19 billion in oil deals.

• Kojo Annan, the son of Kofi Annan (then UN secretary-general), received a $10 million contract.

• Alexander Yakovlev of Russia, senior UN procurement officer, pocketed $1 million.

• Benon Sevan, administrator of the oil-for-food program, received $150,000 in cash.

• France’s former UN ambassador Jean-Bernard Mérimée received $165,725 in oil allocations from Iraq.

• Rev. Jean-Marie Benjamin, assistant to the Vatican secretary of state, received oil allocations under the program.

• Charles Pasqua, former French interior minister and intimate friend of former French president Jacques Chirac, received oil allocations.

• The Communist Party in Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church, and several Russian oil companies all received oil allocations.

In all, 270 separate people received oil vouchers permitting them to buy Iraqi oil at a discount and then sell it at the higher market price, pocketing the difference.

Former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, who investigated the program at the behest of the UN, said, “Corruption of the [oil-for-food] program by Saddam and many participants could not have been nearly so pervasive with more disciplined management by the United Nations.”13

Forty countries and 2,250 companies paid bribes to Saddam under oil-for-food to receive favorable treatment.

No UN official has been criminally prosecuted for bribes or any other crime stemming from the oil-for-food program.

This is the record of corruption at the United Nations. Who can doubt that if the Law of the Sea Treaty is ratified, the billions in oil royalties that flow through the UN will not open the door to the same kind of systematic and universal graft that characterized the oil-for-food program?

New opportunities for corruption-without-consequence are emerging from the initiatives for global governance. If the UN is to administer a vast fund to redistribute wealth to the third world, tax oil royalties from offshore drilling, regulate the Internet, and tax financial transactions and the like, the kleptocracies that make up much of the UN membership can only lick their chops in anticipation.

But won’t the UN enforce rules against corruption as it acquires more power? History indicates that it will do nothing at all to clean up its act.

Indeed, the tendency toward corruption—and the blind eye the UN leadership turned to it—that was evident in the 1990s only accelerated with the start of the new millennium.

In 2005, a huge scandal ripped the UN Procurement Department, which was responsible for all purchases made by the organization. Alexander Yakovlev, the head of the department, pled guilty to federal charges of wire fraud, racketeering, and money laundering. Working with his fellow Russian Vladimir Kuznetsov, the head of the UN Budget Oversight Committee, he tipped off bidders for contracts with inside information in return for bribes. Paul Volcker estimated that the Russians made off with $950,000 in bribes and helped contractors win more than $79 million in UN contracts.14

A year later, the FBI broke up a drug ring operating right out of the UN mailroom that had smuggled 25 tons of illegal drugs into the United States in 2005–2006.15

But what is exceptional about the Yakovlev case and the FBI investigation are not the crimes the UN officials committed, but the fact that they were punished. The case against Yakovlev was brought by the US attorney for the area in which the UN is physically located. The UN not only has never prosecuted one of its own for stealing or anything else, it totally lacks the ability even to try to do so. Such prosecutions of UN officials as the US attorney can bring are the only means of holding UN personnel legally accountable. But these cases are rare because the UN organization systematically hides evidence and permits its delegates to conceal their larceny behind diplomatic immunity.

Volcker complained about what he called “the culture of inaction” that surrounds the UN’s efforts at reform. Indeed, the anti-corruption agency at the international body, the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OSIS), can only investigate UN agencies with their permission. Its funding for these inquiries must come from the budgets of the agencies it investigates. David M. Walker, comptroller-general of the United States, said that “UN funding arrangements constrain OIOS’s ability to operate independently…. OIOS depends on the resources of the funds, programs, and other entities it audits. The managers of these programs can deny OIOS permission to perform work or not pay OIOS for services.”16

Outrage at UN corruption—and the permissive attitude of the secretary-generals toward it—has led to several attempts in recent years at cleaning up the mess. But each has been thwarted, often by the delegates to the General Assembly from third world nations that don’t want their personal candy store to close.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon hired former US attorney Robert Appleton to investigate corruption in the United Nations. Appleton did a very good job, uncovering massive bribery, larceny, bid-rigging, money laundering, and the like all over the world body. He was rewarded for his services by the General Assembly, which defunded his unit, fired him, and blackballed his staff from ever working for the UN again.

All his findings were swept under the UN rug. Appleton said, “As far as I am aware, significant follow-up [to my investigations] was only made in one case, and that was after significant pressure—including from… Congress.”17

Appleton told Congress that “the most disappointing aspect of my experience in the [UN] organization was not with what we found, but the way in which investigations were received, handled, and addressed by the UN administration and the way in which investigations were politicized by certain member states.”18

Another anti-corruption agency, the UN Joint Inspection Unit (JIU), was similarly crushed after it also exposed corruption, particularly in the notorious Procurement Department. The General Assembly’s Senior Review Group fired the director of the JIU and replaced him and his staff with more compliant and less thorough investigators.19

It’s not healthy to investigate UN corruption. On December 11, 2011, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon crippled the UN Dispute Tribunal, a judicial body he himself had established two years before. He stripped its judges of the capacity to protect whistle-blowers. The judges—recruited from outside the UN bureaucracy—charged that the secretary-general who had appointed them was trying to “undermine the integrity and independence” of their court.

Ban Ki-moon stripped the tribunal of its ability to order its decisions to be enforced while they were under appeal to the United Nations Appeals Tribunal. Key was its ability to protect those who had come forward with information from dismissal or demotion. The secretary-general also took away the court’s subpoena power and denied it the right to demand that he “produce a document or witness in response to charges of unjust treatment.”20

This is the same secretary-general who will be given the power to appoint judges to the Law of the Sea Tribunal to adjudicate disputes between the US and other nations should we ratify the LOST.

How can we ever trust him with the power to name the arbiters of the law of the sea and of the resources that lie beneath the waves?

DO THEY RESPECT HUMAN RIGHTS?

Human rights are regularly abused by a great many of the countries with whom we would share our sovereignty if the globalists in the UN have their way. And things are getting worse.

Freedom House notes that

despite a net 37-year gain in support for the values of democracy, multiparty elections, the rule of law, freedom of association, freedom of speech, the rights of minorities and other fundamental, universally valid human rights, the last four years have seen a global decline in freedom. The declines represent the longest period of erosion in political rights and civil liberties in the nearly 40-year history of Freedom in the World. New threats, including heightened attacks on human rights defenders, increased limits on press freedom and attacks on journalists, and significant restrictions on freedom of association have been seen in nearly every corner of the globe.21

To understand the values and ideals of our fellow nations and their rulers, we need to understand the depravity with which many of them treat human beings and their sacred rights. We must understand, as we peruse their terrible records, that each of these nations—criminal gangs really—will have the same vote on UN global councils as we do.

Freedom House published a sad list titled “The Worst of the Worst.” Unfortunately, their list of the most egregious human rights violators includes China, which sits not only in the General Assembly, but also as a permanent member on the Security Council, where it has a veto over all measures.

Here’s the highlights of the Freedom House report of the worst of the worst on human rights in the world:

A former member of the Soviet Union, Belarus is still as tightly controlled today by its dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka as it once was by Stalin. Freedom House reports, “His government… uses police violence and other forms of harassment against the political opposition, and blocked independent media from covering demonstrations through systematic intimidation. After releasing all of its political prisoners in 2008, the regime incarcerated more activists in 2009.”22

“President Lukashenka systematically curtails press freedom,” Freedom House reports. “Libel is both a civil and criminal offense, and an August 2008 media law gives the state a monopoly over information about political, social, and economic affairs. The law gives the cabinet control over Internet media. State media are subordinated to the president, and harassment and censorship of independent media are routine.”23

How comforting that President Lukashenka’s handpicked delegates will have a vote equal to ours on issues of Internet freedom if the new telecommunications regulations are confirmed in December in Dubai!

Pity this poor country. After experiencing Stalin’s abuses before World War II, Hitler during it, and repressive communism after it, Belarus is still ruled by a corrupt, absolute dictator. It can’t catch a break!

Rated as the single most oppressive regime in the world, Burma’s military regime governs by arresting and imprisoning political dissidents.

“The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) rules by decree,” Freedom House reports. “It controls all executive, legislative, and judicial powers, suppresses nearly all basic rights, and commits human rights abuses with impunity. Given the lack of transparency and accountability, corruption and economic mismanagement are rampant at both the national and local levels.”24

“The junta drastically restricts press freedom and owns or controls all newspapers and broadcast media. The authorities practice surveillance at Internet cafes and regularly jails bloggers. Teachers are subject to restrictions on freedom of expression and are held accountable for the political activities of their students. Some of the worst human rights abuses take place in areas populated by ethnic minorities. In these border regions the military arbitrarily detains, beats, rapes, and kills civilians.”25

Freedom House reports that this country located right below the Sahara Desert “has never experienced a free and fair transfer of power through elections. Freedom of expression is severely restricted…. In 2008, the government imposed a new press law that increased the maximum penalty for false news and defamation to three years in prison, and the maximum penalty for insulting the president to five years. Human rights groups credibly accuse the security forces and rebel groups of killing and torturing with impunity.”26 Charming. And the recent discovery of oil will provide even more excuses for murder.

This nation, which sits on the UN Security Council, is the world’s most populous and second richest. But Freedom House reminds us of the disreputable foundations on which its government precariously rests. “The Chinese government, aiming to suppress citizen activism and protests during politically sensitive anniversaries… resorted to lockdowns on major cities, new restrictions on the Internet, and a renewed campaign against democracy activists, human rights lawyers, and religious minorities. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) possesses a monopoly on political power; its nine-member Politburo Standing Committee makes most key political decisions and sets government policy. Opposition groups are suppressed, and activists publicly calling for reform of the one-party political system risk arrest and imprisonment. Tens of thousands are thought to be held in prisons and extrajudicial forms of detention for their political or religious views. Despite thousands of prosecutions launched each year and new regulations on open government, corruption remains endemic, particularly at the local level.”27

“Freedom of the press remains extremely restricted, particularly on topics deemed sensitive by the CCP. During the year, the authorities sought to tighten control over journalists and Internet portals, while employing more sophisticated techniques to manipulate the content circulated via these media. Journalists who do not adhere to party dictates are harassed, fired or jailed.”28

Given China’s efforts to enhance global regulation of the Internet through the United Nations, it is important that while China “is home to the largest number of Internet users globally, the government maintains an elaborate apparatus for censoring and monitoring Internet use, including personal communications, frequently blocking websites it deems politically threatening.”29

In addition, Freedom House notes that “torture remains widespread, with coerced confessions routinely admitted as evidence. Serious violations of women’s rights continue, including domestic violence, human trafficking, and the use of coercive methods to enforce the one-child policy.”30

Robert Zubrin, the author of the new book Merchants of Despair, tells us that between 2000 and 2004, there were 1.25 boys born alive in China to every 1 girl. He concludes, grimly, that this indicates that “one-fifth of all baby girls in China were either being aborted or murdered. In some provinces, the fraction [of girls] eliminated was as high as one-half.”31

Cuba remains stuck in the backwash of its 1957 communist revolution. Freedom House: “Longtime president Fidel Castro and his brother, current president Raul Castro, dominate the one-party political system. The Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) controls all government entities from the national to the local level. All political organization outside the PCC is illegal. Political dissent, whether spoken or written, is a punishable offense, and dissidents frequently receive years of imprisonment for seemingly minor infractions.” In 2009, there were more than two hundred political prisoners in Cuban jails.

“Freedom of the press is sharply curtailed, and the media are controlled by the state and the PCC. Independent journalists are subjected to ongoing repression, including terms of hard labor and assaults by state security agents. Access to the Internet remains tightly restricted, and it is difficult for most Cubans to connect in their homes.”32

President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo is the longest-serving ruler in sub-Saharan Africa. He has been the dictator of this impoverished but oil-rich country for thirty years. CBS News reports that he has been accused “of cannibalism, specifically eating parts of his opponents to gain power.”33 He stays in power by rigging the elections. Freedom House reports that Equatorial Guinea, a country of just seven hundred thousand people, “has never held credible elections [and] is considered one of the most corrupt countries in the world…. Obiang and members of his inner circle continue to amass huge personal profits from the country’s oil windfall. The state holds a near-monopoly on broadcast media, and the only Internet service provider is state affiliated, with the government reportedly monitoring Internet communications. The authorities have been accused of widespread human rights abuses, including torture, detention of political opponents, and extrajudicial killings.”34

On Africa’s eastern horn, Eritrea has a form of conscription that binds people to work for the state for much of their lives. Recently, Freedom House reports, it has “intensified its suppression of human rights… using arbitrary arrests and [its] onerous conscription system to control the population.” Political prisoners languish in prison indefinitely. Privately owned newspapers are banned and “torture, arbitrary detentions, and political arrests are common.”35

The scene of some of the most brutal fighting during the Vietnam War, Laos has mimicked Vietnam in trying to encourage foreign investment. But, as Freedom House reports, it is still a one-party dictatorship and “corruption and abuses by government officials are widespread. Official announcements and new laws aimed at curbing corruption are rarely enforced. Government regulation of virtually every facet of life provides corrupt officials with many opportunities to demand bribes.”36

“Religious freedom is tightly constrained. The government forces Christians to renounce their faith, confiscates their property, and bars them from celebrating Christian holidays. The religious practice of the majority Buddhist population is [also] restricted. Gender-based discrimination and abuse are widespread. Poverty puts many women at greater risk of exploitation and abuse by the state and society at large, and an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Laotian women and girls are trafficked each year for prostitution.”37

The least free nation on earth, North Korea is tightening even further its control and repression of its citizens, according to Freedom House. Armed with nuclear weapons, North Korea is as isolated as ever. An hereditary dictatorship, power is handed down within to the progeny of founder Kim Il-sung. Freedom House reports that “protection of human rights remains nonexistent in practice. Corruption is believed to be endemic at all levels of the state and economy.” The media is tightly censored and controlled and “nearly all forms of private communication are monitored by a huge network of informers.” Things are so bad that even the UN General Assembly has recognized and condemned severe human rights violations, including the use of torture, public executions, extrajudicial and arbitrary detention, and forced labor; the absence of due process and the rule of law; death sentences for political offenses; and a large number of prison camps. The regime subjects thousands of political prisoners to brutal conditions, and collective or familial punishment for suspected dissent by an individual is a common practice.38

Uniquely among the “worst of the worst” human rights abusers, Saudi Arabia is an American ally whose monarchy is sustained and kept in power by the US military. We import one million of the nine million barrels of oil the Saudis produce annually and Europe is even more dependent on the flow of fuel.

In our book Screwed!, we devote lots of space to documenting Saudi human rights abuses. Women are probably suppressed more here than in any other nation on earth… they may not legally drive cars, their use of public facilities is restricted when men are present, and they cannot travel within or outside of the country without a male relative. Daughters receive half the inheritance awarded to their brothers, and the testimony of one man is equal to that of two women in Sharia (Islamic law) courts.39 What a wonderful country to have protected with the lives of our soldiers!

Strategically located on Africa’s eastern horn, Somalia has become a center for al Qaeda terrorists second only to the Afghan-Pakistan border.

Freedom House reports that “the political process is driven largely by clan loyalty. Due to mounting civil unrest and the breakdown of the state, corruption in Somalia is rampant. The office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that there were 1.5 million internally displaced people… most of them living in appalling conditions.”40

This tormented nation is ruled by President Omar al-Bashir, for whom an arrest warrant was issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in March 2009, citing evidence of crimes against humanity and war crimes in Darfur. Meanwhile, the country is torn apart by tensions and war between Islamic Sudan and Southern Sudan, a new nation carved out from Sudan to protect the black minority from Arab terror. Behind the conflict is the oil-rich region of Abyei, mostly part of the north.

Freedom House reports that “the police and security forces practice arbitrary arrest, holding people at secret locations without access to lawyers or their relatives. Torture is prevalent. It is widely accepted that the government has directed and assisted the systematic killing of tens or even hundreds of thousands of people in Darfur since 2003, including through its support for militia groups that have terrorized civilians. Human rights groups have documented the widespread use of rape, the organized burning of villages, and the forced displacement of entire communities. Islamic law denies women equitable rights in marriage, inheritance, and divorce. Female genital mutilation is practiced throughout the country. The restrictions faced by women in Sudan were brought to international attention in 2009 by the case of journalist Lubna Hussein, who was arrested along with several other women for wearing trousers in public. They faced up to 40 lashes under the penal code for dressing indecently.”41

Freedom House also lists Libya and Syria as among the “worst of the worst” but conditions in both nations are too unsettled to report reliably on their futures.

This litany of human rights abuses, governmental corruption, and suppression of democracy underscores our fundamental point: The United States should not surrender its sovereignty or decision-making power to a global body where these international miscreants are given full and equal voting power.

The world we face today is neither democratic nor honest. Neither respectful of human rights nor a guardian of individual liberty. It is dominated by corrupt dictators and one-party governments that do not speak for their people and keep power only by coercion, censorship, and repression.

We dare not trust our liberties to them.

CONCLUSION So What Do We Do About It?

The treaties on gun control and the Law of the Sea are coming up for Senate ratification by the end of the year. President Obama and Hillary hope to ram them through the lame-duck session of the Senate after the elections have been held. In theory, they say they want to consider these documents without the pressures of election-year campaigning. But, in reality, they hope that defeated Democrats and retiring Republicans will give them the votes they need for ratification.

We must stop them!

Fortunately, the decision is in our hands. Democrats control only 53 votes in the Senate and 67 are needed to ratify a treaty. While the House doesn’t get to vote on treaties, the two-thirds requirement in the Senate means that 14 of the 47 Republicans have to join with all the Democrats to get these treaties approved.

That’s where we need to work. In our chapter on the Law of the Sea Treaty, we explain who are the swing votes. The nose count on the Arms Trade Treaty has not been taken yet, but it will likely follow the same pattern. Republicans who are not already opposed to the Law of the Sea Treaty are likely the ones whom we need to persuade to oppose the Arms Trade Treaty.

Because these Republicans are very, very sensitive to the opinions of their GOP backers back home, you can make a key difference. Contact them. Call their offices. Circulate petitions in your neighborhood and send them to their Senate offices. Get your local Republican clubs and other organizations to pass resolutions opposing ratification. Turn on the pressure.

Opposing the Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities and preventing the president from signing on to the International Criminal Court will require broad public agitation. We need to publicize what these documents portend and what their implications are for the future.

We should be able to shoot down the Internet regulations. By arousing online users all over America, we can make it a dead letter even before it is signed. We need to kill it and we must!

Get to work!

In every generation, Americans have been called upon to fight to protect our liberties. Sometimes the threat came from an empire that ruled us. Then it arose from the invidious practice of slavery within our own borders. During the last century we were threatened by European and Japanese dictators who sought global domination. During the Cold War, we faced an ideological adversary who repressed human rights in the name of economic justice. In the War on Terror, we face an enemy that is determined to impose his religious and cultural values on us.

But the globalist adversary is more insidious and a greater threat to our liberty today than we face from any other source. It advances in the name of our own good, seeking to frighten us into line by dire predictions of global disaster unless we give up our sovereignty and share our wealth. Its apocalyptic predictions of environmental catastrophe come like tornado warnings on the prairie, leading us to come and huddle together in our shelters, accepting discipline and a loss of freedom during the emergency. But the emergency is fabricated and the warnings are issued just to panic us into the shelters, where we can be subjugated and tyrannized.

In his book Ameritopia: The Unmaking of America, Mark Levin writes how the desire for the elusive comforts of a utopia can induce men and women to surrender their personal liberty, accepting universal regimentation to achieve what they fantasize will be a greater good.

But fear can have the same effect. And those who would impose a global governance on us count on our worry about climate change, global warming, ocean acidification, rising sea levels, melting glaciers, and shifting rainfall patterns to get us into line behind a new world order.

But we are Americans and our knees don’t bend to tyrants, however disguised.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ