APPENDICES

APPENDIX I Medical aspects of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation

David Hackett, MD, FRCP, FESC.

Consultant Cardiologist, West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust, and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; former Chairman of the Resuscitation Committee, West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust; and former Vice-President of the British Cardiovascular Society.

During the Second World War and in the Korean War the severe injuries inflicted led to surgeons having to extract bullets and shrapnel from many locations in the body including the heart. Previous medical teaching had assumed that any cardiac surgery would be fatal, but many foreign bodies were successfully extracted from the heart without mishap. This led to the dawn of modern heart surgery, and the recognition that many serious heart conditions could be treated. Doctors observed that ventricular fibrillation, a fatal abnormality in cardiac rhythm, could occur in certain circumstances such as during induction of anaesthesia or in the early stages of heart attacks in hearts that were otherwise healthy, ‘hearts that were too good to die’. It was also known that accidental electrocution could induce ventricular fibrillation, and that powerful electric shocks could reverse it. In 1947, the first successful internal defibrillation was performed during an open chest surgical procedure. The first successful external defibrillation was performed in 1955, and in the early 1960s portable defibrillators were developed. In 1967 mobile coronary care units were introduced in Belfast, with successful out-of-hospital defibrillation in patients with acute heart attacks. These developments led to the concept of Emergency Medical Services, to bring medical care to resuscitate the victim at the scene, rather than ‘scoop and run’ to the hospital.

It has been known since the late 19th century that open chest cardiac massage could maintain an effective circulation. Closed chest cardiac massage by compressing the front of the chest against the vertebral spine resulting in compression of the heart and ejection of blood into the arteries was rediscovered in 1960. Mouth-to-mouth ventilation, often used to initiate breathing in a newborn, was shown to maintain oxygenation, and resulted in a switch from more cumbersome manual ventilation techniques. The combination of chest compression and mouth-to-mouth ventilation, or cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, became known as basic life support; this could maintain life for a short time until defibrillation or another definitive procedure was performed.

It has long been recognised that the key elements of survival from cardio-respiratory arrest are early recognition and prompt call for help, early cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, early defibrillation and early advanced medical care. Recent developments to aid out-of-hospital resuscitation include Automated External Defibrillators (AED), which use electrode pads attached to the chest to diagnose the heart rhythm. If ventricular fibrillation is confirmed then both screen display and verbal advice is given to press a button and deliver a defibrillating electric shock. These devices have led to first responder defibrillation, public access defibrillation and home defibrillation. If an ambulance has been called, the dispatcher can provide telephone instructions to direct bystanders to initiate resuscitation while awaiting the arrival of the emergency medical services.

The Resuscitation Council (UK)[8] publishes various guidelines for cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, which are internationally accepted. If someone collapses or is found to be unresponsive, the standard approach follows the pattern Airway, Breathing, Circulation or A B C. Detailed guidance and flow-chart posters can be found in various publications available from the Resuscitation Council website.[9] On discovering a collapsed or unresponsive person, the bystander or professional should call for immediate professional help if in hospital, or telephone the national emergency number if out of hospital. Resuscitation is a team effort, and cannot be performed effectively by an individual.

The first action is to ensure the airway is clear of obstruction from the tongue, mucus or a foreign body. If the circulation is working adequately, the subject is placed in the lateral recumbent or recovery position on their side, which prevents the tongue from obstructing the airway. If there is cardiac arrest, and the patient should remain lying on their back to allow resuscitation, a short plastic tube known as a Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) or other oral airway such as an oro-pharyngeal or Guedel airway is inserted into the throat to keep the upper airway open. In unconscious patients with ongoing cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, a longer tube called an endo-tracheal tube can be inserted from the mouth directly into the windpipe to allow direct ventilation with a manual bag or ventilator; insertion of an endo-tracheal tube is a highly specialised skill usually undertaken by trained paramedical staff or anaesthesiologists.

The second action is to ensure that the subject is breathing. If there is no spontaneous breathing, then mouth-to-mouth ventilation should be commenced, although with this technique there is a risk of infections being transmitted.

The third action is to ensure there is a circulation. If there is no effective circulation, then chest compressions should begin. The most effective circulation is achieved with chest compressions at a rate of about 100 times a minute, or just less than two per second. Ventilation can interfere with chest compressions as the lungs expand, so it has been found that the most effective combination is two ventilations for every thirty chest compressions.

Advanced life support relates to the underlying causes of a cardiorespiratory arrest. If there is no circulation because the heart is in ventricular fibrillation, then only prompt defibrillation with an appropriate electric shock can restore the normal rhythm. If the heart is in an abnormal rhythm and going very fast, such as in ventricular tachycardia, then a defibrillating electric shock can also restore a normal rhythm. Various other treatments can help or restore normal circulation. For example, if during basic life support the circulation is inadequate because of a very slow pulse from heart block (when the electrical impulses that control the beating of the heart are disrupted), medications such as atropine or adrenaline can be given by intravenous injection to speed up the heart rate, and many modern defibrillators can perform external electrical stimulation, which can also increase and pace the heart rate. If blood pressure is inadequate because of a weakened heart, then medications such as adrenaline can be injected to stimulate the force of contraction of the heart thereby raising the blood pressure. Abnormally fast heart rhythm disorders can be treated with anti-arrhythmic drugs, such as amiodarone.

The results of resuscitation depend crucially on where the cardiopulmonary arrest has occurred, and the previous medical history. Resuscitation in hospital should be, and usually is, prompt and more likely to be effective, whereas outside hospital there may be a delay and therefore the outcome is less likely to be as good. Secondly, if there is no previous medical history of cardiopulmonary disorder, and there is good cardiac and lung function, then the outcome can be good; in this circumstance, successful resuscitation can usually result in the patient returning to normal activities and having a normal life expectancy. On the other hand, if there is a history of advanced heart failure or end-stage lung disease, then the outcome is often poor; in this scenario, resuscitation can be technically successful in the very short term, but is unlikely to result in the patient surviving to discharge from hospital. The success rates reported as regards resuscitation from cardiorespiratory arrest will also depend crucially on the selection of patients. If every patient who is dying is resuscitated, then the success rate to survival at discharge from hospital will be low. Conversely, if resuscitation is not attempted on all those patients who are near death from an untreatable condition, and in all others who are considered medically inappropriate to be resuscitated, then the success rate will be much higher.

An audit of 1,368 cardiac arrests occurring in forty-nine hospitals in the United Kingdom in 1997 showed that eighteen per cent of patients were discharged alive, and of these eighty-two per cent were still alive six months later. [10]

In thirty-one per cent of these patients there was a treatable cardiac rhythm disorder such as ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia, and within this group forty-two per cent were discharged alive. If the cause of the cardiac arrest was not an easily treatable cardiac rhythm abnormality, then only six per cent were discharged alive. In this audit, factors associated with an improved chance of survival included an easily treatable cardiac arrhythmia as the cause of the arrest, a prompt return of the circulation in response to cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, and the age of the patient, with those under seventy being more likely to survive. The Resuscitation Council (UK) and The Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) are collaborating to develop a national database regarding cardio-pulmonary arrests that take place in hospital† to enable analysis of the frequency of, and outcome from, resuscitation in the United Kingdom. This should result in more consistent reporting and a better understanding of what might result in improved success rates.

The statistical likelihood of success in cardio-pulmonary resuscitation is not reflected in popular television dramas! A study of ninety-seven episodes of television medical dramas in the United States of America in 1994-1995 analysed sixty occurrences of cardio-pulmonary arrest; sixty-five per cent of these arrests occurred in children, teenagers, or young adults and sixty-seven per cent appear to have survived to hospital discharge.[11] Such rates are significantly higher than even the most optimistic survival rates in the medical literature and the portrayal of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation on television may lead the viewing public to have an unrealistic impression of the procedure, and its chances of success.

In 2004 the Ontario Pre-hospital Advanced Life Support Study of 5,638 patients who had had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest reported that only five per cent survived to discharge from hospital.f There did not seem to be any trend towards improved survival over time with the introduction of community-based initiatives. The registry of cardiac arrests in the community of Goteborg in Sweden reported that of 5,505 patients who had suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest between 1980 and 2000, between eight and nine per cent of these survived to hospital discharge.[12] Again there was no trend towards improvement in survival rates over the time period of the study. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2010 detailing seventy-nine studies of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests involving 142,740 patients reported that twenty-four per cent reached hospital alive, but the rate of survival to hospital discharge was 7.6 per cent overall and this survival rate has remained unchanged over the last thirty years.[13] Again survival ratio depended on many of the same factors as in-hospital cases i.e. the speed of response, whether the patient received cardio-pulmonary resuscitation from a bystander, if the cardiac rhythm abnormality was easily treatable, or if there was an early return of spontaneous circulation.

In 2004, a study of nearly 1,000 communities in twenty-four North American Regions reported that survival to hospital discharge was twenty-three per cent in those areas equipped with staff trained in using Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs), whereas survival was fourteen per cent in those areas without.[14] Increasingly, cardiac arrests which occur out-of-hospital are also being automatically treated by a special type of implanted pacemaker known as an Internal Cardiac Defibrillator (ICD). These have been available for more than ten years, and have been implanted in those people at the highest risk of developing lethal cardiac rhythm disorders. When implanted, the devices promptly diagnose and treat almost all lethal cardiac rhythm disorders within a few seconds, using an internal electric defibrillator shock. The widespread use of these devices might paradoxically skew the statistics regarding survival rates, as those not fitted with the device are likely to have less easily treatable conditions and are therefore less likely to be successfully resuscitated following a cardiac arrest.

In 2006 the Termination of Resuscitation Study investigators in Ontario reported on the development of a theoretical rule which would predict a low chance of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to hospital discharge.[15] Where there was no return of spontaneous circulation, no defibrillation shocks had been administered, and the arrest was not witnessed by the emergency services, the rule recommended termination of resuscitation. Of 776 patients with cardiac arrest for whom the rule recommended termination of resuscitation, only four survived (0.5 per cent) to hospital discharge. If the additional criteria of an emergency services response interval of more than eight minutes, were included, together with the arrest not being witnessed by a bystander, then this rule would have proved 100 per cent accurate. These factors should not be used to avoid resuscitation in all such cases, and they should not be applied automatically or be allowed to over-ride clinical assessments. However, they can be very helpful in judging the value or futility of attempting resuscitation or continuing resuscitation of victims of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Many resuscitations on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest victims are inevitably delayed, and the consequence can be brain injury or damage from lack of circulation and oxygen. It is very difficult to predict the likelihood of recovery from acute brain injury at the time of the arrest, and some patients do make a full recovery.

There are specific circumstances when a full recovery can occur after a long delay, such as cases of electrocution, drowning, hypothermia, poisoning, or anaphylactic (allergic) shock. According to the Resuscitation Council, by three days after the onset of coma related to cardiac arrest, fifty per cent of patients have died.† The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation consensus statement on ‘post cardiac arrest syndrome’ states that the most reliable predictor of a poor outcome (vegetative state or brain death) is the absence of a pupillary light response, corneal reflex, or motor response to painful stimuli at seventy-two hours.[16] On the basis of a systematic review of the literature, absent brain-stem reflexes or a low Glasgow Coma Scale motor score at seventy-two hours is reliable in predicting a poor outcome.

The frequency of prolonged coma or permanent brain disability after resuscitation will depend on the underlying cause of the cardio-pulmonary arrest, and the speed with which resuscitation was undertaken. A study published in 1997 of 464 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Bonn over three years reported that seventy-four patients (sixteen per cent) were discharged from hospital.f Thirty-four (7.3 per cent) were discharged alive without neurological deficit, twenty-two patients (4.7 per cent) were discharged with mild cerebral disability, nine (1.9 per cent) were discharged with severe residual cerebral disability, and a further nine (1.9 per cent) were in a persistent coma.

Traditionally it has been taught that resuscitation should always be attempted in people who have collapsed or in patients whose condition has suddenly deteriorated. The case of Karen Ann Quinlan in the United States of America changed medical practice and provided a focus to moral teaching about death and resuscitation.[17] In 1975, aged twenty-one years old, Karen Ann Quinlan was found unconscious and not breathing in bed shortly after consuming alcohol and drugs at a party. Resuscitation was performed, but she did not regain consciousness and remained in a persistent vegetative state for several months. Her family felt that she would never recover, and wanted to withdraw medical treatment including mechanical ventilation. Medical and hospital staff refused, on the basis that this would result in her intended and hastened death; the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that the patient or their guardian had the right to determine their treatment, that medical staff had no rights independent of the patient, and that there was no obligation for medical staff to use extraordinary means to preserve life. This ruling confirmed the principle that medical treatment could be withdrawn, and resuscitation did not necessarily have to be attempted. Karen Ann Quinlan became known as the ‘right to die’ case.

The case also resulted in clarification of the legal status of ‘Do Not Attempt Resuscitation’ orders, and the concept of advanced directives with regard to possible future scenarios or treatments. It reaffirmed the idea that a patient always has the right to refuse extraordinary means of treatment, even if it will hasten their death. Furthermore, the Karen Ann Quinlan case resulted in the establishment of Ethics Committees in many hospitals to provide guidance to clinical staff in situations where patients do not consent to recommended treatments, or where unreasonable treatment is demanded.

If a heart attack is treated promptly with defibrillation, and if other emergency treatment prevents damage to the heart, the patient can often return to a normal life and have a normal life expectancy. Clearly resuscitation in this circumstance would be worthwhile. On the other hand, if a patient with an advanced disease, such as terminal cancer or terminal lung failure, develops a sudden lethal cardiac rhythm disorder, successful resuscitation might result in limited benefit, such as survival for a few more days or weeks, potentially in the context of receiving intensive medical care. Many people would regard this second example of resuscitation as futile, or of limited value. Between these two examples are many shades of grey, and it is good medical practice to try to establish the likely value or futility of emergency resuscitation in each patient during acute illness or admission to hospital. It is also good medical practice to try to think about the likely value of undertaking emergency resuscitation if someone has a chronic progressive and untreatable condition.

A discussion about the benefits or futility of resuscitation can be difficult for someone if they have not considered the matter beforehand, particularly in the case of a newly diagnosed acute illness with limited treatment or with a grave prognosis. On the other hand, most people will want to talk, learn about and discuss their illness, especially when they are anxious or frightened. Talking about the prognosis should be a natural part of the discussion, although doctors often do not raise the subject of death if patients do not ask, and patients can be too uncertain or too frightened to ask. In my experience most people prefer quality of life to longevity but occasionally people will want to keep going for a specific reason even if they are very unwell, such as a family event like the wedding of a son or daughter, the birth of a grandchild, or the completion of an important project.

Questions about resuscitation are not usually a simple yes or no decision. For example, most people who are not in an advanced terminal illness would want to be resuscitated from a simple cardiac rhythm disturbance or from transient difficulty in breathing due to infection, but often would not want prolonged intensive care with supportive treatment on an artificial ventilator or on kidney dialysis. Thus, any clinical discussion of resuscitation should include what types of resuscitation might be undertaken, and how far-reaching these directives might be. If the conclusion is that the person does not want to be resuscitated from their current illness, then this wish must be respected, and a note or statement made in their medical records to this effect. This statement should be as precise as possible, for example: ‘this person does not wish to be resuscitated from a cardio-respiratory arrest’. When patients have decided that they do not wish to be resuscitated, almost all hospitals have specific ‘Do Not Attempt Resuscitation’ (DNAR) forms for completion by an experienced doctor. There is a model DNAR form, as well as a model patient information leaflet, available on the Resuscitation Council website.[18] Most hospitals also have a resuscitation committee, which will agree local policies on the application of Do Not Attempt Resuscitation decisions, and audit the appropriateness of these orders.

It can take a considerable amount of time for doctors to explain resuscitation issues to patients, and for clinicians to understand the wishes of the patient - such discussions are usually sensitive, exploratory and wide-ranging, and often require several conversations. Modern hospital practice usually involves shift work, and often there are several different doctors looking after each patient. It is essential that the clinical team makes time to discuss resuscitation decisions with each patient, and that there is a consistent response from each clinician.

Almost every hospital has introduced Do Not Attempt Resuscitation policies, procedures and forms, and clinical staff have become better at discussing death and resuscitation with patients. For those involved in hospice care and palliative care teams, however, the management of death goes well beyond the issue of whether to resuscitate or not. An alternative, more positive way of thinking about death in people with advanced disease is labelled Allow a Natural Death’ (AND).[19] Allowing a natural death simply means not interfering with the dying process whilst providing care that will keep the patient as comfortable as possible. Allow a Natural Death orders are intended for terminally ill patients who are being cared for in hospices, care homes or at home, but there is no reason why these should not be applied to patients in acute hospital wards as well. The NHS Gold Standards Framework enables generic care providers, such as primary care, care homes, and palliative care settings to deliver a gold standard of care for all people nearing the end of their life, [20] and there is an ‘Allow a Natural Death’ form on their website.[21] The Avon, Somerset and Wiltshire Cancer Services also have an ‘Allow a Natural Death’ form on their website.[22] Dignity in Dying is an organisation dedicated to ensuring choice about where to die, who is present during death and treatment options, and provides access to expert information, good quality end-of-life care, support for loved ones and carers, together with advice on symptoms, and pain relief [23] A decision to ‘Allow a Natural Death’ should be communicated in writing by professional clinicians to the local Ambulance or Emergency Services dispatch control centre to avoid resuscitation if that person should unexpectedly collapse. However, at present there are no national arrangements or systematic ways of communicating DNAR orders across all potential healthcare settings. We already use national NHS consent and DNAR forms in our hospitals, so it should not be difficult to extend this and register such forms with the emergency services; Advanced Directives or “Living Wills” could also be included. Of course, a DNAR form or Advanced Directive would need to satisfy the various legal requirements of a written document: it must be signed by the patient and a witness, the patient must have demonstrated adequate mental capacity to make the decision at the time, and the order or directive would have to be applicable to their current illness or condition. Safeguards against fraudulent entries and the influence of overzealous relatives would be necessary - for example, the witness and co-signatory might be a person who knows the patient in a professional capacity, such as their GP, solicitor, priest or minister. Arrangements could be made for patients to reregister or renew these documents annually. Obviously, legal and confidentiality safeguards would also be required with regard to the sharing of the information contained in these forms across different emergency services and healthcare organisations. Such forms could be stored electronically and shared online so that when an emergency call is received about a patient with a DNAR order or Advanced Directive, this would immediately be flagged up and the contents notified to the emergency controller.

Clinical staff are not obliged to offer resuscitation to every patient; doctors do not have to offer or provide treatments that are futile. If a patient has an advanced terminal illness with no realistic chance of improvement, doctors do not have to undertake resuscitation in the event of a cardio-respiratory arrest; it would be considered unethical. However, sometimes a patient or their family cannot accept that unavoidable death may be close, and insist that ‘everything must be done’. Where there is a persistent discrepancy between the views of the patient or their family and the clinical staff, it is good medical practice to seek additional opinions and advice from experienced doctors not directly involved in the case.

The General Medical Council in The United Kingdom has published guidance on ‘Treatment and care towards the end of life: Good practice in decision making’.[24] This guidance is based on long-established ethical principles, which include a doctor’s obligation to show respect for human life; to protect the health of patients; to treat patients with respect; and to make the care of their patient their first concern. Patients who are approaching the end of their life need high-quality treatment and care to help them to live as well as possible until they die, and to die with dignity. The guidance identifies a number of challenges in ensuring that patients receive such care, and provides a framework to support doctors in addressing the issues in a way that will meet the needs of individual patients. It emphasises the importance of communication between clinicians and healthcare teams when patients move between different care settings (hospital, ambulance, care home), and during any out-of-hours period. Failure to communicate relevant information can lead to inappropriate treatment being given or failure to meet the patient’s needs.

Decisions relating to resuscitation cannot be made by patients who are not mentally capable of understanding their condition, the obvious example being when the patient is unconscious. A patient must be able to understand, retain, and weigh information about themselves, and be able to communicate in some form, in order to make a rational decision about their medical care.

There are variations in different jurisdictions regarding the legal tests and requirements to determine whether a patient has the mental capacity to make such decisions, but the general medical principles are common to most circumstances. In order to demonstrate effective mental capacity, a person should be able to understand what the medical treatment is, its purpose and nature, and why it is being proposed; as well as comprehending its benefits, risks and the alternatives; they must understand, in broad terms, what will be the consequences of not receiving the proposed treatment; be able to weigh the information in the balance to arrive at a choice; retain the information for long enough to make an effective decision; and make a free choice without external pressure. Different medical treatments may require different levels of mental capacity; for example, the consent process for having a blood sample taken requires a lower degree of weighing and retaining information, compared with the consent process for major, life-threatening cardiac or abdominal surgery. If a patient lacks the mental capacity to make a decision about their care, this should be noted in their medical records, and the clinical reasons for it.

If a patient lacks adequate mental capacity, then the decision must be made for them in their best interests and urgent medical interventions can be performed, particularly in the case of emergency or life-saving treatments. In the case of serious procedures to be done without consent, it is good medical practice to consider alternative, less invasive treatments; to discuss treatment with all members of the healthcare team; to discussing treatment with the patient as far as possible; to consult with other healthcare professionals involved with the patient’s care (for example, their general practitioner); to consult relatives, partners and carers; to obtain further opinions from experienced doctors if the patient or their family do not agree with the proposed treatment; and to ensure a record is made of the discussions and any decision taken.

Again, there are variations on the legal requirements in different jurisdictions. Good medical practice would include consultation with relatives, partners and carers to ascertain what the expected wishes of the patient might be. In England and Wales, the Mental Capacity Act of 2005 has brought a legal obligation for clinicians to take into account the views of anyone named or appointed with power of attorney by the patient for this purpose, their carers, or any deputy appointed by a court.[25]

In an unexpected or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, when the patient cannot consent to treatment, the assumption has to be that resuscitation should be performed. Death can be verified by any appropriately qualified person, but this is usually done by a doctor, and in the United Kingdom only a doctor who has provided care during the last illness and who has seen the deceased within fourteen days of death or after death can sign a death certificate. If someone is found to have collapsed and died, the emergency services are still obliged to attempt resuscitation as they cannot in general immediately ascertain the underlying condition of the victim. Of course if a person has been dead for some time, for several hours or longer, death will be obvious and resuscitation attempts will not be appropriate.

Age itself should not be a deciding factor when discussing whether to resuscitate someone who has collapsed, when discussing whether to continue resuscitation attempts, or when discussing whether a patient would wish to be resuscitated or not from a cardio-pulmonary arrest. In general, the success of any medical treatment decreases with age, but there is no specific cutoff point concerning the success of resuscitation from cardiopulmonary arrest. Furthermore, clinical policies should not be ageist in terms of specifying treatments that are not provided to people over a certain age, unless there is very good medical evidence to suggest a lack of benefit. In the medical literature about resuscitation, there is no evidence that the outcome is dependent on being under a certain chronological age, or that failure occurs over a certain age. The benefits of most medical treatments depend on the general condition of the patient, therefore discussions about the value or futility of resuscitation should be based on that rather than the patient’s chronological age.

This is a reason why the most useful information when deciding whether to undertake or continue cardio-pulmonary resuscitation is the medical history. If, for example, a patient has presented with an exacerbation of breathlessness from chronic, extensive and end-stage respiratory failure, uses home oxygen and is house-bound as a consequence of their condition, then resuscitation from a cardiorespiratory arrest is less likely to be successful, and the prospect of a full recovery is unlikely. If such a patient is placed on a mechanical ventilator to take over their breathing and oxygenation, it could be very difficult to wean them off. If, on the other hand, a patient has been healthy and active until recently, and presents with respiratory failure due to extensive pneumonia, then resuscitation is more likely to be successful, and the chances of a full recovery are good. It is often the current or future quality of life that is the influential factor when assessments about resuscitation are being made by clinicians and families or carers on behalf of a patient.

A successful resuscitation can be evident within minutes, but it may not be evident for perhaps thirty minutes or more that resuscitation has been unsuccessful; basic and advanced life-support measures can maintain the breathing and circulation for this length of time and longer. Decisions about when to stop resuscitation attempts are usually made by an experienced doctor when there has been no response, and there is no treatable or reversible cause of the initial collapse. As previously observed, resuscitation should be continued for longer than usual in specific circumstances, such as in the case of children or where the collapse has been caused by electrocution, drowning, hypothermia, poisoning, or anaphylactic shock.

Advanced Decisions, advanced directives, or ‘living wills’ can be made to specify treatment that a person might or might not want in the future. There are three legal requirements for Advanced Decisions to be honoured – existence, validity and applicability – and these have been set out for England and Wales in the Mental Capacity Act (2005).

For an Advanced Decision to be considered existent, it must be put down in writing, and be signed by the patient and a witness. For it to be valid, the Advanced Decision must not have been withdrawn or overridden by a subsequent Lasting Power of Attorney, and the patient must not have acted in a way that is clearly inconsistent with the Advanced Decision. To be applicable, the person must have had the mental capacity to make the decision about the proposed treatment at the time of writing. The Advanced Decision will not be applicable to treatments or circumstances that are not specified in the document. If there is any doubt or dispute about whether a particular advanced decision meets all the requirements, action may be taken to prevent the death or serious deterioration of the patient, whilst the dispute is referred to legal authorities. It is always very difficult to anticipate every possible scenario with regard to your health and healthcare, and therefore advanced decisions can be very limited in scope, especially when a patient presents with a new illness or condition.

Parents will almost always ask to be present when their child is being resuscitated. Historically, as with most medical procedures, relatives have been kept outside when cardio-pulmonary resuscitation is being performed. However, there are differing views between the public and healthcare professionals and the Resuscitation Council has published a useful document on their website about this issue.[26]

From the relatives’ and partners’ point of view, being present may help them come to terms with the serious illness or death of a loved one, especially when they can see that everything medically appropriate has been done. The disadvantage is that the reality of resuscitation may prove distressing, particularly if it is traumatic or if they are uninformed. Furthermore, they may physically or emotionally hinder the staff involved in the resuscitation attempt. However, it seems likely that for many relatives it is more distressing to be separated from their family member during these critical moments than to witness them. From the patient’s point of view, most would probably want to have their family present but it would be unusual for the patient to have expressed an advanced directive stipulating the inclusion of specific relatives, partners, carers or friends. For the clinical staff undertaking resuscitation, the presence of relatives could increase stress, affect decision-making, and affect the performance of the staff involved. On the other hand, verbal or physical interference by a relative could be prevented by close supervision and restriction of numbers.

Progressives believe that relatives or partners should be given the opportunity to be with their loved ones at this time, and proper provision must be made for those who indicate that they wish to stay. If resuscitation is to be witnessed by relatives, partners or carers, it is essential that they be supported throughout by appropriately trained clinical staff, and that the resuscitation team leader is prepared for and aware of their presence. Every hospital should have a written policy about the procedure to be followed when relatives, partners or carers request to be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and this would normally be the responsibility of the local Resuscitation Committee.

Modern resuscitation methods and techniques date from the many major advances in research and development of medical practice in the 1950s and 1960s. Changes since then have mainly resulted in improvements in existing procedures, rather than in the development of new medical treatments; consequently, improvements in the outcome of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation have been relatively small. The introduction of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation in the 1960s, as with many new drugs or medical procedures, resulted in initial scepticism, followed by enthusiasm, leading to over-enthusiasm and over-use, until a more precisely defined usage becomes established. With the development of procedures, medical practice has run ahead of many of the moral and ethical issues involved in resuscitation decisions. Most of these issues, such as the applicability of Do Not Attempt Resuscitation orders and Advanced Decisions, are now being reassessed so that they come into line with current medical practice.

In general, the success rates of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation remain disappointingly low, especially in out-of-hospital resuscitation, and it does not seem likely that developments in the near future will substantially help to improve the situation. In my view, the most helpful development would be for clinicians to be able to define in advance which people and which conditions are most likely to have a successful outcome, and which will not; there is an obvious need to be more selective about for whom, when and where we undertake cardio-pulmonary resuscitation although this is clearly much easier to do for patients in hospital.

Sudden collapse and death are in fact very rare in healthy people, and are probably becoming even rarer in countries that have falling mortality rates from heart disease. The greatest challenge is to understand when there is likely to be little or no benefit from cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and to identify more systematically those people in advance. By doing this, death could be managed in a better and more humane way – which is the whole point of this book.

In the end, doctors cannot cheat death; we can only delay it.

APPENDIX II THE PARAMEDIC’S TALE

By Louise Massen, Clinical Team Leader, Thameside Ambulance Station, South East Coast Ambulance Service (SECAMB)

I joined Kent Ambulance Service on the i April 1993.I am second-generation ambulance service and absolutely love my job with a passion! There is nothing else I ever want to do.

We received a three-month residential training course, which was run by a specialist ambulance training college. The course encompassed emergency driving, manual handling, and the specialist ambulance aid skills required to use the equipment we need to treat a whole host of medical, traumatic and obstetric calls.

I graduated in July 1993 and was posted to Dartford Ambulance Station of North Kent. I was proud to work at the station where my father had worked for twenty years. In his day, the ambulance equipment consisted of a basic stretcher, some oxygen, a few bandages and wooden splints, and lots of blankets. I was trained in manual cardiac defibrillation, could take a blood pressure, and use a whole host of splinting and moving equipment to handle the high-speed trauma that we were increasingly being called to deal with.

By 1995 I had completed the extended training by the National Health Service Training Directorate (NHSTD), and was deemed a ‘qualified ambulance paramedic’. My new skills included intravenous cannulation and infusion (this meant I could insert a needle over a catheter into a patient’s vein to administer IV drugs or fluids), endotracheal intubation (a plastic tube which sits in the patient’s trachea or windpipe to facilitate a patent airway whilst unconscious), intraosseous cannulation (screwing a needle into a bone to allow drug access), and a more detailed approach to cardiac ECG interpretation.

Surely and slowly, medical progress has been made and many new protocols, policies and procedures have found their way into the ambulance service. Paramedics these days are proficient in 12-lead ECG interpretation, can diagnose and provide definitive treatment for myocardial infarction by administering thrombolytic clot-busting drugs – every minute a coronary artery is occluded depletes life by about eleven days – so our early intervention and treatment in the pre-hospital setting is improving the quality of many patients’ lives, as well as the quantity who survive.

New paramedics, these days, are trained by universities with the emphasis more on education and less on the sort of vocational training that I completed. The new cohorts of paramedics are selected from those who successfully complete a three-year degree course, with the opportunity for all paramedics to extend their training to become paramedic practitioners (PPs) and critical care paramedics (CCPs).

The paramedical degree courses are separated into academic modules covering a range of subjects such as introduction to medical care, trauma care, public health immunology, and foundations of paramedic practice, which covers use of ambulance equipment and clinical skills, and the different sections of anatomy and physiology which are broken down into the various systems of the body – cardiology, neurology etc.

In the first year, the student paramedics cover all the basic education, and by year two they train alongside established paramedics and work as part of an ambulance crew (although they are not allowed to practise autonomously). As the course continues, they learn new practical skills, and complete various hospital and clinical placements to complete their education. Clinical skills are practised under the supervision of experienced paramedics, who have also completed a practice placement educators’ (PPEDs) course.

At the end of three years, all the education, clinical skills and experience from working on the front line allows the students to join the ranks of the rest of us registered as paramedics by the Health Professions Council. Every paramedic has to re-register every two years and maintain evidence of clinical professional development to remain on the register – failure to do so could result in a paramedic losing their registration and being unable to practise, in the same way as doctors and nurses must show development.

Our PPs and CCPs undergo degree-level education for an additional eighteen months, and, once qualified, have even more developed examination skills, and can provide more comprehensive roadside care to the patients in the community and at home – our PP clinicians can provide catheter care, perform suturing and wound closure, prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics and, in some areas, are working alongside general practitioners in facilitating diabetic or asthma clinics.

Our CCPs are working alongside doctors and anaesthetists in providing cutting edge front-line care to those patients most critically ill, working on helicopters and specialist ambulances equipped to transfer patients in drug-induced comas safely between hospitals. This reduces the need to use doctors to look after anaesthetised patients.

Our area now encompasses Kent, Surrey and Sussex in the South East Coast Ambulance Service or SECAMB. The newest advances include a FASTrack Stroke Pathway – we work very closely with all our hospitals so that, when we are dispatched to a patient showing a positive test for a stroke, we can deliver them directly to the nearest hospital able to deliver thrombolytic therapy to dissolve the clot. Stroke patients are now being discharged home and are back at work in weeks – a long way from the treatment a few years ago, when a stroke victim was likely to be paralysed for months, years, or worse.

SECAMB is also the first ambulance trust in the UK fully to follow a new cardiac arrest protocol for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest where the first rhythm is ventricular fibrillation.

SECAMB is now delivering resuscitation based on emphasis for effective cardiac compression, which has been championed by our honorary life medical director, the world-renowned cardiologist Professor Douglas Chamberlain, CBE, who has, for many years, been our greatest advocate, and has worked tirelessly training paramedics.

Our Protocol C resuscitation procedure for patients presenting in ventricular fibrillation is leading the way in pre-hospital resuscitation in the UK. Some of the latest clinical audits published in 2009 for survival following cardiac arrest rate SECAMB as the highest performing ambulance service in the country.

So what exactly does happen when a member of the public dials 999 to a collapsed patient who is terminally ill? Our role is to preserve life, prevent deterioration and promote recovery – but can we always achieve this? What is the dilemma that we, as ambulance paramedics, face when we are called to a patient at the end stage of their illness?

All ambulance service clinicians – technicians, paramedics and advanced paramedics – work within the guidelines of the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC). These guidelines are very specific, and state that in the event of being called to a cardiac arrest or near life-threatening event we are obliged to initiate resuscitation unless we have sight of a formal Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) order or an Advance Directive to Refuse Treatment.

A patient who is deemed to have mental capacity has the right to refuse treatment, even if not having that treatment leads to deterioration in health and ultimately death. A patient who is unconscious cannot make that decision; it has to be made for them – and in those circumstances, in the absence of any lasting power of attorney by a relative, all steps of active resuscitation would be undertaken unless a DNAR is shown to the ambulance crew.

This formal DNAR must be in writing and given to the crew on arrival at the call. The condition must relate to the condition for which the DNAR is written, so resuscitation should not be withheld for coincidental conditions.

In the case of a known terminally ill patient being transferred to a palliative care facility, the DNAR can be verbally received and recorded by ambulance control.

In an out-of-hospital emergency environment, there may be situations where there is doubt about the validity of an advance refusal or DNAR order. If the ambulance crew are not satisfied that the patient has made a prior and specific request to refuse treatment, they are obliged to continue all clinical care in the normal way.

I am constantly reminded of how my decisions to provide clinical care for patients I attend can have a lasting effect on quite often distressed and highly emotional relatives, who have witnessed the sudden collapse of a cherished one and act on impulse by calling an ambulance … I have the equipment, the knowledge and the clinical skills to initiate and continue advanced life support and resuscitation, and in the absence of any written order I have to do so … Or is this always the case?

I may be ‘just’ a paramedic, but I have empathy with the suffering of the sick. That’s why I am a paramedic and do the job that I do, surely?

Whilst I am very aware that many members of the public urge us to do ‘everything we can’ to save a life, my seventeen years of ambulance service experience have shown me that a good many elderly or terminally ill patients do not require the services of a paramedic; in their time of need, they want peace, or a priest, or, in some cases, both. That is the area that I will now go on to discuss.

About ten years ago I was working on the night shift. It was a little after midnight when the crew received a call to attend a ‘ninety-six-year-old female, breathing difficulty’. We arrived shortly after the call was made and knocked on the door at the address we were given. An elderly man opened the door, and gestured for us to follow him. We traipsed into the house with our equipment and were led into the front room where a very elderly lady lay on a single bed in front of a fireplace.

The lights were dimmed, but I could see that the lady was dying. Her breathing was bubbly, laboured and intermittent. She was unconscious and her eyes were shut, but she was twitching a little bit. My eye caught an empty ampoule of diamorphine discarded on the mantelpiece.

The man began to tell us his story. The lady in the bed was his ninety-six-year-old sister. He was ninety-four, and had lived with her all of his life. My crewmate and I exchanged nervous glances, and the distress visible in her face was most probably echoed in mine. He continued that she had been diagnosed with cancer a couple of years ago and had fought it bravely, but was now nearing the end and had expressed her wish to die at home – in the comfort of her own bed, in the house where she was born, with her brother for company. He realised that the time was near and was scared. He was terrified of her dying, and wanted to make sure she wasn’t suffering.

The family doctor had visited in the afternoon and given her a pain-killing injection. She had been sleeping peacefully ever since, but in the last hour her breathing had become increasingly worrying to him and she had begun twitching.

He couldn’t get hold of his doctor, and the GP surgery had redirected his enquiry to the out-of-hours doctors; they had simply instructed him to dial 999. That is how we ended up there.

We sat down and reassured the man. ‘We’ll phone the out-of-hours doctor back, ask for the palliative care nurses to come and be with you and get her some more pain relief so she isn’t in any pain.’ He was so grateful; you could see the tension lift from his face.

I made the phone call and explained the situation to the out-of-hours doctor, and said that we required a palliative visit. He refused point blank to attend and ordered me to take that poor dying lady from her nice warm bed to the accident and emergency department. I was nearly speechless, but attempted to reason with him that it was inhumane to suggest such a thing, the lady was dying and nothing we could do could halt the fact. He adamantly refused to consider it. He was the doctor, I was only the ambulance ‘driver’ and was not in a position to disobey his request. ‘Com-passionless’ was my thought, or maybe something stronger, I regret to admit.

How do you explain this to a distressed relative? That you have to drag his dying sister unceremoniously out of her deathbed and cart her off to the local accident and emergency centre, to be poked and prodded, and then breathe her last on a hospital trolley surrounded by the drunks and assaults that frequent A&E during the night shift? But he was understanding; we had no alternative but to obey medical orders.

We went and fetched our carrying chair, two big warmed blankets and a pillow to prop her up. I knelt on the bed behind her, and, as we lifted her into a semi-sitting position before settling her into the chair, she died.

I looked at my teammate and she nodded. We laid the woman straight back down in the bed, still warm from where we had lifted her up, smoothed her eyes over and covered her with the quilt.

I went to fetch her brother from the kitchen, and we all cried. How unprofessional, I hear you say! I knew in my heart it was the best thing for her. I phoned the out-of-hours doctor again, informing him that now the lady had died, he would have to visit and confirm death (in those days we did not perform recognition of life extinct).

Having personal experience as a relative also puts a whole new perspective on the whole end-of-life-care issue. This is something that I experienced for myself in 2008 when my own mother died from a chronic lung condition. It was the spiritual epiphany of this event that spurred me on to help our ambulance service develop a better insight into end-of-life care and how we can be of benefit to patients who are dying.

The death of my dear mother was, without a doubt, the most life-altering event of my existence.

She had a condition known as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She had lived with this for many years, but had been particularly unwell for the year preceding her death, and was being looked after mainly by the respiratory team at home where she had her own oxygen and nebulisers. She had suddenly been admitted to hospital with an exacerbation of the condition. The consultant told my elderly stepfather, Bernard, that there was nothing more they could do for her except ‘keep her comfortable’.

Mum was only sixty, and it was not until I went to visit her in hospital and saw her so ill that the terrible truth dawned on me that she was dying. I gathered the family round.

It was the most numbing and distressing thirty-six hours of my entire forty years. My brother Matthew (also a paramedic) rushed down from his home in East Anglia. We sat beside her all night and had some deeply intriguing conversations during those dark hours.

‘It’s quite ironic, isn’t it?’ mused Matt. ‘If either one of us received an emergency call to a patient of Mum’s age, who was unconscious and breathing like this, we would be intubating her, nebulising drugs, giving intravenous diuretics and rushing her into A&E as fast as we could.’

He had a point, and yet we sat there, helpless, while Mum’s breathing continued to bubble and struggle, the relentless dull sound of the oxygen hissing away, a constant background noise making my head spin. In the small hours of the night she grew distressed and started moaning and twitching. I went to find a nurse for some help. The doctor wrote her up for some morphine which the staff nurse administered. I asked her how long it would be; Mum’s vital signs were all over the place, her breathing and pulse rate were hugely elevated and her oxygen saturations very low. She had a raging temperature of 40.1.I wasn’t used to watching people die – I was meant to stop that sort of thing from happening. I was shivering on the little chair next to her, my hand tightly grasping hers, its heat keeping me warm in the depth of the night. Another doctor popped in to see Mum. I was beginning to panic.

‘I want to take her home to die,’ I stuttered.

‘It’s not an option now,’ replied the doctor. ‘I cannot discharge her like this, so close to death.’

It was a truly desperate feeling watching my mother dying, aching to swing into action and ‘do my paramedic stuff,’ when, deep inside, I knew there was absolutely nothing I could do to prevent the inevitable slide into death. Mum’s was as dignified as it could be in the little side room. Both Matthew and I held her hands and watched as her breathing slowly began to fail – when we were finally able to rid her of the oxygen mask – and saw the peaceful look come over her face when her exhausted heart eventually stopped beating.

It gave us both a whole new perspective on death and how it affects those it leaves behind.

We both returned to work, vowing to look into the end-of-life care policies our respective ambulance trusts had in place.

As a coincidence, in June 2008, the Darzi Report was issued by the Department of Health, with the title High Quality Care for All. Some of the concerns raised by Lord Darzi included those surrounding end-of-life care. I happened to glimpse some information on this review and begged my Chief Executive Paul Sutton to consider the possibility of championing end-of-life care for SECAMB NHS Trust. He was enthusiastic about my interest, and, with his encouragement, I attended a conference on the subject in November, and found it extremely engaging.

On the back of that conference – and by talking and writing to some of the speakers and delegates – I was invited to speak at the National Council for Palliative Care conference at Guy’s Hospital in March 2009 on the subject of ‘Dying Differently’. My intention was to speak to the delegates and impress on them the fact that ambulance crews are not just there to perform CPR and dash the patient to hospital, but we can also have a place with palliative care patients, even if it is just to administer pain relief or oxygen.

In the past year our Trust has implemented a general policy surrounding Do Not Attempt Resuscitation and Advance Directive to Refuse Treatment. Any palliative care team can email our Trust with a copy of these orders, and we have the facility to add a history marker linked to an address where a palliative care patient lives, so if an emergency call is generated for that person, the information is passed to the crew that the patient is not to be resuscitated.

Indeed, this facility also extends to GPs and hospital consultants who have patients who have requested DNAR for a variety of conditions – COPD (like my mother), advanced Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or any other illness or condition where CPR is deemed inappropriate. The only thing we require to enable us to safeguard ourselves is the sight of the original unaltered document that is signed by the doctor on arrival at the call.

These DNAR documents have no expiry date and, once signed, are valid until the patient dies or the order is changed for whatever reason.

DNAR in most cases would refer to CPR only, but also has the flexibility to allow withholding other treatment such as artificial nutrition and hydration – although these treatments tend to apply to patients already in hospital. Other ambulance services are working around the Allow a Natural Death (AND) procedure.

What is encouraging, of course, is that the ambulance service is now very much part of the integrated multi-disciplined team, and is consulted by the various primary care trusts in end-of-life care issues; and our concerns and wishes are being registered and used, helping us all with the treatment and services we can offer to patients as they reach the end of their natural lives.

Advancement in training, education, and the ever-increasing policies and protocols we follow now, will no doubt lead to an older, and healthier, nation. It is an amazing fact that treatments that we currently use already lead to heart attack and stroke patients recovering fully and going back to ‘tax paying’ status in a few short weeks. Twenty years ago, these patients would have died, or become paralysed for the rest of their lives.

I often chat with my work colleagues and ask them the searching question, ‘Have you thought about how and where you would prefer to die?’

I am surprised that most of them haven’t even thought about their own death, or what their personal preference is. This alarms me, considering the amount of death we actually deal with in our line of work!

For my own part, should I be suffering from an incurable illness, I will be instructing my GP and get my own DNAR written out, and I will leave it in a big white envelope just by the front door - in the hope that the young, keen ambulance crew who come rushing in will take note, and leave me to die in the peace I hopefully have earned!

APPENDIX III Should patients at the end of life be given the option of receiving CPR?

by Madeline Bass, BSc, RGN, Head of Education, St Nicholas Hospice, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

First published in Nursing Times; 105 4, 26-02-2009.

Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is often unsuccessful and may not always be appropriate at the end of life. This article debates whether the use of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation by healthcare professionals in situations when it is unlikely to be successful feeds an unhealthy appetite to intervene just because it is possible. It explores the problem of offering patients and relatives the choice about CPR at the end of life when it is likely to be unsuccessful.

End-of-life and palliative care has become an increasingly important area of healthcare professionals’ work following publication of the End of Life Care Strategy (Department of Health, 2008).

Good communication between patients and staff is essential for those who are making choices and decisions about care at the end of life. This may include discussions about cardio-pulmonary resuscitation.

We can now treat disease and disability in ways that would not have been thought possible sixty years ago. These achievements have also created bioethical dilemmas. The advent of new treatment interventions has brought its own unhealthy appetite - the more treatments healthcare workers have to offer, the more they intervene. To them, this equates with doing the best for patients and knowing that everything has been tried.

However, in some cases, interventions can mean poor outcomes for the patient and result in low staff morale. One area of particular concern is the decision about when it is appropriate to perform CPR.

The media’s interpretation of CPR, primarily through TV drama, has led to a misunderstanding that it is a quick intervention that guarantees success without any side-effects (Bass, 2003; Diem et al, 1996).

CPR was first used in its present advanced life-support format of chest compressions, ventilation and defibrillation in i960 (Kouwenhoven et al, 1960). The main problem associated with CPR is identifying when it is appropriate to instigate it as a life-saving measure. The concern is that the decision to proceed is often viewed as the default if a decision about resuscitation has not been made.

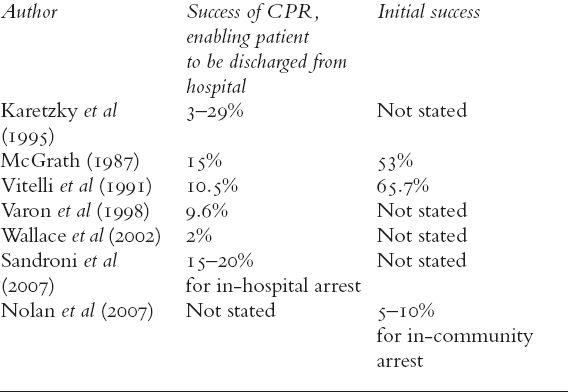

CPR was devised as an emergency intervention for unexpected cardiac or respiratory arrest (Kouwenhoven et al, i960) and the majority of healthcare professionals are not aware that the success rates for CPR are very low (Wagg et al, 1995; Miller et al, 1993) (see Table 1). Only a small percentage of people will survive to leave hospital following a cardiac or respiratory arrest.

Ewer et al (2001) looked at the success rates of CPR undertaken on patients with cancer. They asked whether patients were expected to have an irreversible cardiac or respiratory arrest. The results showed that, of patients having an unexpected, reversible arrest, there was a 22.2% success rate. However, for those who were expected to have an irreversible arrest and were at the end of life, there was 0% success.

The effects of inappropriate CPR are often not considered. These include post-resuscitation disease (complications caused by resuscitation itself) (Negovsky and Gurvitch, 1995), an undignified death for the patient, and distress to relatives. Paramedics and resuscitation teams may also become demoralised by repeated failures (Jevon, 1999).

Table 1. Success rates for CPR

The success of CPR is often measured in terms of initial success - the return of heartbeat and breathing, controlled independently by the patient. It is also measured in terms of survival to discharge (see Table 1). The chances of successful CPR are improved if

There is early access to a cardiac arrest team

Basic life support is commenced immediately

Defibrillation is carried out as quickly as possible in cases of ventricular tachycardia or pulseless ventricular fibrillation (Jevon, 2002).

Other positive factors associated with a successful CPR attempt include:

A non-cancer diagnosis

Cancer without metastases

The patient is not housebound

Good renal function

No known infection

Blood pressure within normal range

The patient has robust health (Newman, 2002).

The Gold Standard Framework (GSF) suggests that cancer, organ failure, general frailty and dementia are not associated with success (NHS End of Life Programme, 2007).

The BMA et al (2007) recommended that CPR should not be attempted when patients have indicated before the cardiac arrest that they would refuse it or if the attempt is likely to be futile because of their medical condition.

Discussions about resuscitation at the end of life raise a number of questions.

Are public expectations of healthcare and technology unrealistic?

Do healthcare professionals pursue the possibility of an immediate positive outcome from CPR without considering the long-term consequences of the intervention?

Does inappropriate CPR raise false hope in patients, relatives and staff? (Jevon, 1999)

Awareness and knowledge of CPR guidance among healthcare professionals is poor (Bass, 2003), with knowledge focusing on local policy rather than research evidence and national guidance.

In addition, healthcare professionals often fail to recognise when a patient is dying, which can result in difficulty making an appropriate decision about whether to resuscitate in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest. The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) is a recommended national tool that can assist professionals to make an accurate diagnosis of dying (Ellershaw and Ward, 2003). This diagnosis can help to inform discussion about when to initiate CPR.

The inappropriate use of CPR can be reduced by improving communication between all members of the multidisciplinary team. The End of Life Care Strategy (DH, 2008) gives guidance and outcomes for care at the end of life, including dignity, appropriate care and comfort – appropriate care should include refraining from undertaking inappropriate CPR.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 allows patients to make advance care plans and allows them to have choices at the end of life. If they are to support patients in making such plans, healthcare professionals need to discuss appropriate choices with them.

It is good practice to have a local Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) policy, and use the documentation from the GSF for patients in their own home. The framework prompts healthcare professionals to initiate discussions around advance care planning, such as about what patients want at the end of their life and whether they have choices.

The GSF also encourages healthcare professionals to ask the question: ‘Would I be surprised if this person died in one year/one month/one week/one day?’ The patient is coded and specific guidance for this coding is given. The coding is:

A: prognosis of years

B: prognosis of months

C: prognosis of weeks

D: prognosis of days.

Guidance relating to the coding provides information about what professionals should discuss with patients and care that should be planned and provided.

For example, if a patient is in the last few weeks of life, then drugs such as analgesics should be available in the person’s home in case they are needed. This can prevent a crisis if these drugs are required at short notice. Depending on the patient’s condition, the coding is reviewed regularly to take into account any changes.

The majority of GP practices in England have now adopted the GSF in some format, but how it is adopted and adapted depends on individual GP practices.

Patient choice is high on the health and social care agenda (Department of Health 2008; 1991; Mental Capacity Act 2005) but this can lead to patients being offered unrealistic choices that are not supported by expert professional opinion. The wrong choice can result in a negative outcome for the patient.

In my experience, there is a misconception among some nurses, doctors and patients that all patients/carers should be given a choice about resuscitation.

Many nurses will have experience of doctors entering a patient’s room when they are in the last few days of life and asking the family carers: ‘If your relative’s heart and lungs stop working, do you want us to resuscitate them?’ In some situations, the family carers are adamant that they do not want this. However, where death is approaching much more quickly than expected, or when it has been difficult for family carers to accept their relative’s approaching death, they may decide that they want CPR.

This can leave healthcare professionals with an ethical dilemma – the family carers want everything to be done, but CPR itself is not an appropriate intervention, so what should they do when the patient dies? The choice is to initiate CPR or to risk a complaint and possible litigation if they do not.

CPR guidance from the BMA et al (2007) does not help healthcare professionals with this dilemma. It states that if patients insist they want CPR, even if it is deemed to be futile, it should be carried out but, when an arrest occurs, the situation should be reviewed. In reality, this means that the patient is offered an intervention that will not be given. This does not support a trusting relationship between healthcare professionals and the patient (Bass, 2008).

Patients or family carers cannot demand CPR and healthcare professionals are not required by law to give a futile treatment. So why is CPR offered at the end of their life when other interventions, such as surgery, would not be considered?

The National Council for Palliative Care (2002a) states that: ‘There is no ethical obligation to discuss CPR with the majority of patients receiving palliative care for whom such treatment, following assessment, is judged futile.’

Written guidance on how to decide if someone is appropriate for CPR has been developed by Randall and Regnard (2005). They produced a flow chart that asks whether the person is expected to have a cardiac or respiratory arrest from a reversible or irreversible cause. If the cause is reversible and there is a chance that CPR would be successful, the patient should be asked whether they would or would not like it, should they go into cardiac or respiratory arrest. If the cause is irreversible and there is no chance of success from CPR, then it should not be offered.

End-of-life care does not have to be complex.

Patients and family carers need to be kept informed about care plans.

Keep the treatment plan simple by only offering interventions that are appropriate for that individual as this is less confusing.

CPR should not be offered when it is deemed to be futile.

Involve the multidisciplinary team in discussions about end of life.

If your place of work does not have a Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) policy, it is important to highlight this. All staff should also be aware of the BMA et al (2007) resuscitation guidelines. The National Council for Palliative Care (2002b) has published a document that offers guidance on how to write a local DNAR policy. If you work for an NHS trust, always consult your local policy and guidelines group.

If there is a chance of successful CPR, then the intervention should be discussed with the patient. If the patient does not have capacity, then evidence of advance care planning, either written or verbal, should be sought. If there is no evidence of either, the patient’s representatives should be asked what they think the patient would want. Alternatively, an independent mental capacity adviser (IMCA) or a court of protection decision may be required.

If CPR is not going to be successful, it should not be offered. The aims of care should be discussed with the patient.

I would argue that nurses are not equipped through basic training to deal with the stress and psychological trauma that patients and family carers are dealing with at the end of life. Nurses develop these skills through experience, reflection and self-awareness. Nurses can support those who are at the end of life by:

Refining their communications skills

Offering appropriate interventions

Checking the patient understands what is happening

Using appropriate terminology.

Good communication includes active listening – this is hearing what is said as well as paying attention to what is communicated in non-verbal ways such as body language.

It is not possible to guess how someone will feel about CPR as there are huge discrepancies between what we think patients want and what they actually want (Jevon, 1999).

We need to make sure that patients and families understand that saying no to CPR does not mean they are saying no to all interventions.

Treatment interventions that are unlikely to be successful should not be offered.

The CPR guidelines state that each resuscitation decision should be discussed, where appropriate, with the individual or their representative (BMA et al, 2007). However, ‘discussion’ does not necessarily mean asking the patient or family to make a decision. Discussion may involve talking things over, finding out what the person’s understanding of the current situation is, and outlining the treatment aims (Bass, 2006). This can be achieved by asking the question, ‘What is your understanding of what has been happening to you/your relative up to now?’ Alternative questions such as ‘Are you the sort of person who likes to know what is going on?’ can be helpful.

These questions may show that the patient understands much more than first thought, or that they would rather you discussed interventions with someone else, for example their family or carers.

Patients may have heard what has been said but have not retained the information. They may have difficulty taking in what has been said either because they cannot believe it, or they do not understand the terminology used. It is important to check a patient’s understanding and provide written information if appropriate to reinforce what has been said.

Using appropriate terminology

It may not be appropriate to use the term ‘resuscitation’ when discussing end-of-life care with patients. Simple phrases stating that at the time of death you will not attempt ‘anything heroic’, but will ‘do all we can to make sure you are comfortable’, are extremely useful.

By making sure we communicate well, and by using tools such as the GSF, LCPI, DNAR policies and advance care planning documentation, nurses can ensure that they are supporting their patients at the end of life.

Awareness of when CPR is appropriate and careful assessment and care planning by the multidisciplinary team will ensure that patients are only offered interventions that are beneficial.

Bass, M. (2008) Resuscitation: knowing whether it is right or wrong. European Journal of Palliative Care; 15:4, 175-178.

Bass, M. (2006) Palliative Care Resuscitation. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Bass, M. (2003) Oncology nurses’ perceptions of their role in resuscitation decisions. Professional Nurse; 18:12, 710-713.

British Medical Association, Resuscitation Council (UK), RCN (2007) Decisions relating to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. A joint statement from the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council UK and the Royal College of Nursing. London: BMA, RCUK, RCN.

Department of Health (2008) End of Life Care Strategy. London: DH.

Department of Health (1991) The Patient’s Charter. London: DH.

Diem, S J et al. (1996) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television. New England Journal of Medicine; 334: 24, 1758-1582.

Ellershaw, J, Ward, C. (2003) Care of the dying patient; the last hours or days of life. British Medical Journal; 326: 7374, 30-34.

Ewer, M S et al. (2001) Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after CPR. Cancer; 92: 7, 1905- 1912.

NHS End of Life Programme (2007) Prognostic Indicator Guidance.

Jevon, P. (2002) Advanced Cardiac Life Support: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

Jevon, P. (1999) Do not resuscitate orders: the issues. Nursing Standard; 13: 40, 45-46.

Karetzky, PEet al. (1995) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in intensive care unit and non-intensive care patients. Archives of Internal Medicine; 155: 12, 1277-1280.

Kouwenhoven, W B et al. (i960) Closed chest cardiac compressions. Journal of the American Medical Association; 173: 1064-1067.

McGrath, R B. (1987) In-house cardiopulmonary resuscitation after a quarter of a century. Annals of American Medicine; 16: 12, 1365-1368.

Miller, DLet al. (1993) Factors influencing physicians in recommending in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Archives of Internal Medicine; 153: 17, 1999-2003.

National Council for Palliative Care (2002a) Ethical Decision-making in Palliative Care. London: NCPC.

National Council for Palliative Care (2002b) CPR Policies in Action. London: NCPC.

Negovsky V A, Gurvitch, A M. (1995) Post-resuscitation disease: a new nosological entity. Its reality and significance. Resuscitation; 30: 1, 23-27.

Newman, R. (2002) Developing guidelines for resuscitation in palliative care. European Journal of Palliative Care; 9: 2, 60-63.

Nolan, J P et al. (2007) Outcome following admission to UK intensive care units after cardiac arrest: a secondary analysis of the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Anaesthesia; 62: 12,1207-1216.

Randall, F, Regnard, C. (2005) A framework for making advance decisions on resuscitation. Clinical Medicine; 5: 4, 354-360.

Sandroni, C et al. (2007) In-hospital cardiac arrest: incidence, prognosis and possible measures to improve survival. Intensive Care Medicine; 33: 2, 237-245.

Varon, J et al. (1998) Should a cancer patient be resuscitated following an in-hospital cardiac arrest? Resuscitation; 36: 3, 165- 168.

Vitelli, C et al. (1991) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and the patient with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology; 9: 1, 111-115.

Wagg, A et al. (1995) Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: doctors and nurses expect too much. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians; 29: 1, 20-24.

Wallace, K et al. (2002) Outcome and cost implications of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the medical intensive care unit of a comprehensive cancer centre. Supportive Care in Cancer; 10: 5, 425-429.

Acute respiratory failure 2 - nursing management. 16 September 2008

An audit of nursing observations on ward patients. 24 July 2008

Guidelines focus on improving patient safety in mental health. 28 November 2008