HE CAME WITH THE RAIN

The scene of this third story is also laid in Peng-lai about half a year later. In the meantime Judge Dee's two wives and their children arrived in Peng-lai, and settled down in the magistrate's private residence at the back of the tribunal compound. Shortly afterwards, Miss Tsao joined the household. In Chapter XV of The Chinese Gold Murders the terrible adventure from which Judge Dee extricated Miss Tsao has been described in detail. When Judge Dee's First Lady met Miss Tsao, she took an instant liking to her and engaged her as her lady-companion. Then, on one of the hottest, rainy days of mid-summer, there occurred the strange case related in the present story.

'This box won't do either!’ Judge Dee's First Lady remarked disgustedly. 'Look at the grey mould all along the seam of this blue dress!’ She slammed the lid of the red-leather clothes-box shut, then turned to the Second Lady. 'I've never known such a hot, damp summer. And the heavy downpour we had last night! I thought the rain would never stop. Give me a hand, will you?'

The judge, seated at the tea-table by the open window of the large bedroom, looked on while his two wives put the clothes-box on the floor, and went on to the third one in the pile. Miss Tsao, his First Lady's friend and companion, was drying robes on the brass brazier in the corner, draping them over the copper-wire cover above the glowing coals. The heat of the brazier, together with the steam curling up from the drying clothes, made the atmosphere of the room nearly unbearable, but the three women seemed unaware of it.

With a sigh he turned round and looked outside. From the bedroom here on the second floor of his residence one usually had a fine view of the curved roofs of the city, but now everything was shrouded in a thick leaden mist that blotted out all contours. The mist seemed to have entered his very blood, pulsating dully in his veins. Now he deeply regretted the unfortunate impulse that, on rising, had made him ask for his grey summer robe. For that request had brought his First Lady to inspect the four clothes-boxes, and finding mould on the garments, she had at once summoned his Second and Miss Tsao. Now the three were completely engrossed in their work, with apparently no thought of morning tea, let alone breakfast. This was their first experience of the dog-days in Peng-lai, for it was just seven months since he had taken up his post of magistrate there. He stretched his legs, for his knees and feet felt swollen and heavy. Miss Tsao stooped and took a white dress from the brazier.

'This one is completely dry,' she announced. As she reached up to hang it on the clothes-rack, the judge noticed her slender, shapely body. Suddenly he asked his First Lady sharply: 'Can't you leave all that to the maids?'

'Of course,' his First replied over her shoulder. 'But first I want to see for myself whether there's any real damage. For heaven's sake, take a look at this red robe, dear!' she went on to Miss Tsao. 'The mould has absolutely eaten into the fabric! And you always say this dress looks so well on me!’

Judge Dee rose abruptly. The smell of perfume and stale cosmetics mingling with the faint odour of damp clothes gave the hot room an atmosphere of overwhelming femininity that suddenly jarred on his taut nerves. 'I'm just going out for a short walk,' he said.

'Before you've even had your morning tea?' his First exclaimed. But her eyes were on the discoloured patches on the red dress in her hands.

'I'll be back for breakfast,' the judge muttered. 'Give me that blue robe over there!’ Miss Tsao helped the Second put the robe over his shoulders and asked solicitously: 'Isn't that dress a bit too heavy for this hot weather?'

'It's dry at least,' he said curtly. At the same time he realized with dismay that Miss Tsao was perfectly right: the thick fabric clung to his moist back like a coat of mail. He mumbled a greeting and went downstairs.

He quickly walked down the semi-dark corridor leading to the small back door of the tribunal compound. He was glad his old friend and adviser Sergeant Hoong had not yet appeared. The sergeant knew him so well that he would sense at once that he was in a bad temper, and he would wonder what it was all about.

The judge opened the back door with his private key and supped out into the wet, deserted street. What was it all about, really? he asked himself as he walked along through the dripping mist. Well, these seven months on his first independent official post had been disappointing, of course. The first few days had been exciting, and then there had been the murder of Mrs Ho, and the case at the fort. But thereafter there had been nothing but dreary office routine: forms to be filled out, papers to be filed, licences to be issued. ... In the capital he had also had much paperwork to do, but on important papers. Moreover, this district was not really his. The entire region from the river north was a strategic area, under the jurisdiction of the army. And the Korean quarter outside the East Gate had its own administration. He angrily kicked a stone, then cursed. What had looked like a loose boulder was in fact the top of a cobblestone, and he hurt his toe badly. He must take a decision about Miss Tsao. The night before, in the intimacy of their shared couch, his First Lady had again urged him to take Miss Tsao as his Third. She and his Second were fond of her, she had said, and Miss Tsao herself wanted nothing better. 'Besides,' his First had added with her customary frankness, 'your Second is a fine woman but she hasn't had a higher education, and to have an intelligent, well-read girl like Miss Tsao around would make life much more interesting for all concerned.' But what if Miss Tsao's willingness was motivated only by gratitude to him for getting her out of the terrible trouble she had been in? In a way it would be easier if he didn't like her so much. On the other hand, would it then be fair to marry a woman one didn't really like? As a magistrate he was entitled to as many as four wives, but personally he held the view that two wives ought to be sufficient unless both of them proved barren. It was all very difficult and confusing. He pulled his robe closer round him, for it had begun to rain.

He sighed with relief when he saw the broad steps leading up to the Temple of Confucius. The third floor of the west tower had been converted into a small tea-house. He would have his morning tea there, then walk back to the tribunal.

In the low-ceilinged, octagonal room a slovenly dressed waiter was leaning on the counter, stirring the fire of the small tea-stove with iron tongs. Judge Dee noticed with satisfaction that the youngster didn't recognize him, for he was not in the mood to acknowledge bowing and scraping. He ordered a pot of tea and a dry towel and sat down at the bamboo table in front of the counter.

The waiter handed him a none-too-clean towel in a bamboo basket. 'Just one moment please, sir. The water'll be boiling soon.' As the judge rubbed his long beard dry with the towel, the waiter went on, 'Since you are up and about so early, sir, you'll have heard already about the trouble out there.' He pointed with his thumb at the open window, and as the judge shook his head, he continued with relish, 'Last night a fellow was hacked to pieces in the old watchtower, out there in the marsh.'

Judge Dee quickly put the towel down. 'A murder? How do you know?'

"The grocery boy told me, sir. Came up here to deliver his stuff while I was scrubbing the floor. At dawn he had gone to the watchtower to collect duck eggs from that half-witted girl who lives up there, and he saw the mess. The girl was sitting crying in a corner. Rushing back to town, he warned the military police at the blockhouse, and the captain went to the old tower with a few of his men. Look, there they are!’

Judge Dee got up and went to the window. From this vantage-point he could see beyond the crenellated top of the city wall the vast green expanse of the marshlands overgrown with reeds, and further on to the north, in the misty distance, the grey water of the river. A hardened road went from the quay north of the city straight to the lonely tower of weather-beaten bricks in the middle of the marsh. A few soldiers with spiked helmets came marching down the road to the blockhouse halfway between the tower and the quay.

'Was the murdered man a soldier?' the judge asked quickly. Although the area north of the city came under the jurisdiction of the army, any crime involving civilians there had to be referred to the tribunal.

'Could be. That half-witted girl is deaf and dumb, but not too bad-looking. Could be a soldier went up the tower for a private conversation with her, if you get what I mean. Ha, the water is boiling!'

Judge Dee strained his eyes. Now two military policemen were riding from the blockhouse to the city, their horses splashing through the water that had submerged part of the raised road.

'Here's your tea, sir! Be careful, the cup is very hot. I'll put it here on the sill for you. No, come to think of it, the murdered man was no soldier. The grocery boy said he was an old merchant living near the North Gate — he knew him by sight. Well, the military police will catch the murderer soon enough. Plenty tough, they are!' He nudged the judge excitedly. 'There you are! Didn't I tell you they're tough? See that fellow in chains they're dragging from the blockhouse? He's wearing a fisherman's brown jacket and trousers. Well, they'll take him to the fort now, and ...'

"They'll do nothing of the sort!' the judge interrupted angrily. He hastily took a sip from the tea and scalded his mouth. He paid and rushed downstairs. A civilian murdered by another civilian, that was clearly a case for the tribunal! This was a splendid occasion to tell the military exactly where they got off! Once and for all.

All his apathy had dropped away from him. He rented a horse from the blacksmith on the corner, jumped into the saddle and rode to the North Gate. The guards cast an astonished look at the dishevelled horseman with the wet house-cap sagging on his head. But then they recognized their magistrate and sprang to attention. The judge dismounted and motioned the corporal to follow him into the guardhouse beside the gate. 'What is all this commotion out on the marsh?' he asked.

'A man was found murdered in the old tower, sir. The military police have arrested the murderer already; they are questioning him now in the blockhouse. I expect they'll come down to the quay presently.'

Judge Dee sat down on the bamboo bench and handed the corporal a few coppers. 'Tell one of your men to buy me two oilcakes!'

The oilcakes came fresh from the griddle of a street vendor and had an appetizing smell of garlic and onions, but the judge did not enjoy them, hungry though he was. The hot tea had burnt his tongue, and his mind was concerned with the abuse of power by the army authorities. He reflected ruefully that in the capital one didn't have such annoying problems to cope with: there, detailed rules fixed the exact extent of the authority of every official, high or low. As he was finishing his oilcakes, the corporal came in.

"The military police have now taken the prisoner to their watch-post on the quay, sir.'

Judge Dee sprang up. 'Follow me with four men!’

On the river quay a slight breeze was dispersing the mist. The judge's robe clung wetly to his shoulders. 'Exactly the kind of weather for catching a bad cold,' he muttered. A heavily armed sentry ushered him into the bare waiting-room of the watchpost.

In the back a tall man wearing the coat of mail and spiked helmet of the military police was sitting behind a roughly made wooden desk. He was filling out an official form with laborious, slow strokes of his writing-brush.

'I am Magistrate Dee,' the judge began. 'I demand to know ...' He suddenly broke off. The captain had looked up. His face was marked by a terrible white scar running along his left cheek and across his mouth. His misshapen lips were half-concealed by a ragged moustache. Before the judge had recovered from this shock, the captain had risen. He saluted smartly and said in a clipped voice:

'Glad you came, sir. I have just finished my report to you.' Pointing at the stretcher covered with a blanket on the floor in the corner, he added, "That's the dead body, and the murderer is in the back room there. You want him taken directly to the jail of the tribunal, I suppose?'

'Yes. Certainly,' Judge Dee replied, rather lamely.

'Good.' The captain folded the sheet he had been writing on and handed it to the judge. 'Sit down, sir. If you have a moment to spare, I'd like to tell you myself about the case.'

Judge Dee took the seat by the desk and motioned the captain to sit down too. Stroking his long beard, he said to himself that all this was turning out quite differently from what he had expected.

'Well,' the captain began, 'I know the marshland as well as the palm of my hand. That deaf-mute girl who lives in the tower is a harmless idiot, so when it was reported that a murdered man was lying up in her room, I thought at once of assault and robbery, and sent my men to search the marshland between the tower and the riverbank.'

'Why especially that area?' the judge interrupted. 'It could just as well have happened on the road, couldn't it? The murderer hiding the dead body later in the tower?'

'No, sir. Our blockhouse is located on the road halfway between the quay here and the old tower. From there my men keep an eye on the road all day long, as per orders. To prevent Korean spies from entering or leaving the city, you see. And they patrol that road at night. That road is the only means of crossing the marsh, by the way. It's tricky country, and anyone trying to cross it would risk getting into a swamp or quicksand and would drown. Now my men found the body was still warm, and we concluded he was killed a few hours before dawn. Since no one passed the blockhouse except the grocery boy, it follows that both the murdered man and the criminal came from the north. A pathway leads through the reeds from the tower to the riverbank, and a fellow familiar with the layout could slip by there without my men in the blockhouse spotting him.' The captain stroked his moustache and added, 'If he had succeeded in getting by our river patrols, that is.'

'And your men caught the murderer by the waterside?'

'Yes, sir. They discovered a young fisherman, Wang San-lang his name is, hiding in his small boat among the rushes, directly north of the tower. He was trying to wash his trousers which were stained with blood. When my men hailed him, he pushed off and tried to paddle his boat into midstream. The archers shot a few string arrows into the hull, and before he knew where he was he was being hauled back to shore, boat and all. He disclaimed all knowledge of any dead man in the tower, maintained he was on his way there to bring the deaf-mute girl a large carp, and that he got the blood on his trousers while cleaning that carp. He was waiting for dawn to visit her. We searched him, and we found this in his belt.'

The captain unwrapped a small paper package on his desk and showed the judge three shining silver pieces. 'We identified the corpse by the visiting-cards we found on it.' He shook the contents of a large envelope out on the table. Besides a package of cards there were two keys, some small change, and a pawn-ticket. Pointing at the ticket, the captain continued, 'That scrap of paper was lying on the floor, close to the body. Must have dropped out of his jacket. The murdered man is the pawnbroker Choong, the owner of a large and well-known pawnshop, just inside the North Gate. A wealthy man. His hobby is fishing. My theory is that Choong met Wang somewhere on the quay last night and hired him to take him out in his boat for a night of fishing on the river. When they had got to the deserted area north of the tower, Wang lured the old man there under some pretext or other and killed him. He had planned to hide the body somewhere in the tower — the thing is half in ruins, you know, and the girl uses only the second storey — but she woke up and caught him in the act. So he just took the silver and left. This is only a theory, mind you, for the girl is worthless as a witness. My men tried to get something out of her, but she only scribbled down some incoherent nonsense about rain spirits and black goblins. Then she had a fit, began to laugh and to cry at the same time. A poor, harmless half-wit.' He rose, walked over to the stretcher and lifted the blanket. 'Here's the dead body.'

Judge Dee bent over the lean shape, which was clad in a simple brown robe. The breast showed patches of clotted blood, and the sleeves were covered with dried mud. The face had a peaceful look, but it was very ugly: lantern-shaped, with a beaked nose that was slightly askew, and a thin-lipped, too large mouth. The head with its long, greying hair was bare.

'Not a very handsome gentleman,' the captain remarked. 'Though I should be the last to pass such a remark!’ A spasm contorted his mutilated face. He raised the body's shoulders and showed the judge the large red stain on the back. 'Killed by a knife thrust from behind that must have penetrated right into his heart. He was lying on his back on the floor, just inside the door of the girl's room.' The captain let the upper part of the body drop. 'Nasty fellow, that fisherman. After he had murdered Choong, he began to cut up his breast and belly. I say after he had killed him, for as you see those wounds in front haven't bled as much as one would expect. Oh yes, here's my last exhibit! Had nearly forgotten it!’ He pulled out a drawer in the desk and unwrapped the oiled paper of an oblong package. Handing the judge a long thin knife, he said, 'This was found in Wang's boat, sir. He says he uses it for cleaning his fish. There was no trace of blood on it. Why should there be? There was plenty of water around to wash it clean after he had got back to the boat! Well, that's about all, sir. I expect that Wang'll confess readily enough. I know that type of young hoodlum. They begin by stoutly denying everything, but after a thorough interrogation they break down and then they talk their mouths off. What are your orders, sir?'

'First I must inform the next of kin, and have them formally identify the body. Therefore, I ...'

'I've attended to that, sir. Choong was a widower, and his two sons are living in the capital. The body was officially identified just now by Mr Lin, the dead man's partner, who lived together with him.'

'You and your men did an excellent job,' the judge said. 'Tell your men to transfer the prisoner and the dead body to the guards I brought with me.' Rising, he added, 'I am really most grateful for your swift and efficient action, captain. This being a civilian case, you only needed to report the murder to the tribunal and you could have left it at that. You went out of your way to help me and ...'

The captain raised his hand in a deprecatory gesture and said in his strange dull voice, 'It was a pleasure, sir. I happen to be one of Colonel Meng's men. We shall always do all we can to help you. All of us, always.'

The spasm that distorted his misshapen face had to be a smile. Judge Dee walked back to the guardhouse at the North Gate. He had decided to question the prisoner there at once, then go to the scene of the crime. If he transferred the investigation to the tribunal, clues might get stale. It seemed a fairly straightforward case, but one never knew.

He sat down at the only table in the bare guardroom and settled down to a study of the captain's report. It contained little beyond what the captain had already told him. The victim's full name was Choong Fang, age fifty-six; the girl was called Oriole, twenty years of age, and the young fisherman was twenty-two. He took the visiting-cards and the pawn-ticket from his sleeve. The cards stated that Mr Choong was a native of Shansi Province. The pawn-ticket was a tally, stamped with the large red stamp of Choong's pawnshop; it concerned four brocade robes pawned the day before by a Mrs Pei for three silver pieces, to be redeemed in three months at a monthly interest of 5 per cent.

The corporal came in, followed by two guards carrying the stretcher.

'Put it down there in the corner,' Judge Dee ordered. 'Do you know about that deaf-mute girl who lives in the watchtower? The military police gave only her personal name — Oriole.'

'Yes, sir, that's what she is called. She's an abandoned child. An old crone who used to sell fruit near the gate here brought her up and taught her to write a few dozen letters and a bit of sign language. When the old woman died two years ago, the girl went to live in the tower because the street urchins were always pestering her. She raises ducks there, and sells the eggs. People called her Oriole to make fun of her being dumb, and the nickname stuck.'

'All right. Bring the prisoner before me.'

The guards came back flanking a squat, sturdily built youngster. His tousled hair hung down over the corrugated brow of his swarthy, scowling face, and his brown jacket and trousers were clumsily patched in several places. His hands were chained behind his back, an extra loop of the thin chain encircling his thick, bare neck. The guards pressed him down on his knees in front of the judge.

Judge Dee observed the youngster in silence for a while, wondering what would be the best way to start the interrogation. There was only the patter of the rain outside, and the prisoner's heavy breathing. The judge took the three silver pieces from his sleeve.

'Where did you get these?'

The young fisherman muttered something in a broad dialect that the judge didn't quite understand. One of the guards kicked the prisoner and growled: 'Speak louder!'

'It's my savings. For buying a real boat.'

'When did you first meet Mr Choong?'

The boy burst out in a string of obscene curses. The guard on his right stopped him by hitting him over his head with the flat of his sword. Wang shook his head, then said dully, 'Only knew him by sight because he was often around on the quay.' Suddenly he added viciously: 'If I'd ever met him, I'd have killed the dirty swine, the crook ...'

'Did Mr Choong cheat when you pawned something in his shop?' Judge Dee asked quickly.

'Think I have anything to pawn?'

'Why call him a crook then?'

Wang looked up at the judge who thought he caught a sly glint in his small, bloodshot eyes. The youngster bent his head again and replied in a sullen voice: 'Because all pawnbrokers are crooks.'

'What did you do last night?'

'I told the soldiers already. Had a bowl of noodles at the stall on the quay, then went up river. After I had caught some good fish, I moored the boat on the bank north of the tower and had a nap. I'd planned to bring some fish to the tower at dawn, for Oriole.'

Something in the way the boy pronounced the girl's name caught Judge Dee's attention. He said slowly, 'You deny having murdered the pawnbroker. Since, besides you, there was only the girl about, it follows it was she who killed him.'

Suddenly Wang jumped up and went for the judge. He moved so quickly that the two guards only got hold of him just in time. He kicked them but got a blow on his head that made him fall down backwards, his chains clanking on the floor-stones.

'You dog-official, you ...' the youngster burst out, trying to scramble up. The corporal gave him a kick in the face that made his head slam back on the floor with a hard thud. He lay quite still, blood trickling from his torn mouth.

The judge got up and bent over the still figure. He had lost consciousness.

'Don't maltreat a prisoner unless you are ordered to,' the judge told the corporal sternly. 'Bring him round, and take him to the jail. Later I shall interrogate him formally, during the noon session. You'll take the dead body to the tribunal, corporal. Report to Sergeant Hoong and hand him this statement, drawn up by the captain of the military police. Tell the sergeant that I'll return to the tribunal as soon as I have questioned a few witnesses here.' He cast a look at the window. It was still raining. 'Get me a piece of oiled cloth!'

Before Judge Dee stepped outside he draped the oiled cloth over his head and shoulders, then jumped into the saddle of his hired horse. He rode along the quay and took the hardened road that led to the marshlands.

The mist had cleared a little and as he rode along he looked curiously at the deserted, green surface on either side of the road. Narrow gullies followed a winding course through the reeds, here and there broadening into large pools that gleamed dully in the grey light. A flight of small water birds suddenly flew up, with piercing cries that resounded eerily over the desolate marsh. He noticed that the water was subsiding after the torrential rain that had fallen in the night; the road was dry now, but the water had left large patches of duck-weed. When he was about to pass the blockhouse the sentry stopped him, but he let him go on as soon as the judge had shown him the identification document he carried in his boot.

The old watchtower was a clumsy, square building of five storeys, standing on a raised base of roughly hewn stone blocks. The shutters of the arched windows had gone and the roof of the top storey had caved in. Two big black crows sat perched on a broken beam.

As he came nearer he heard loud quacking. A few dozen ducks were huddling close together by the side of a muddy pool below the tower's base. When the judge dismounted and fastened the reins to a moss-covered stone pillar, the ducks began to splash around in the water, quacking indignantly.

The ground floor of the tower was just a dark, low vault, empty but for a heap of old broken furniture. A narrow, rickety flight of wooden stairs led up to the floor above. The judge climbed up, seeking support with his left hand from the wet, mould-covered wall, for the bannisters were gone.

When he stepped into the half-dark, bare room, something stirred among the rags piled up on the roughly made plank-bed under the arched window. Some raucous sounds came from under a soiled, patched quilt. A quick look around showed that the room only contained a rustic table with a cracked teapot, and a bamboo bench against the side wall. In the corner was a brick oven carrying a large pan; beside it stood a rattan basket filled to the brim with pieces of charcoal. A musty smell of mould and stale sweat hung in the air.

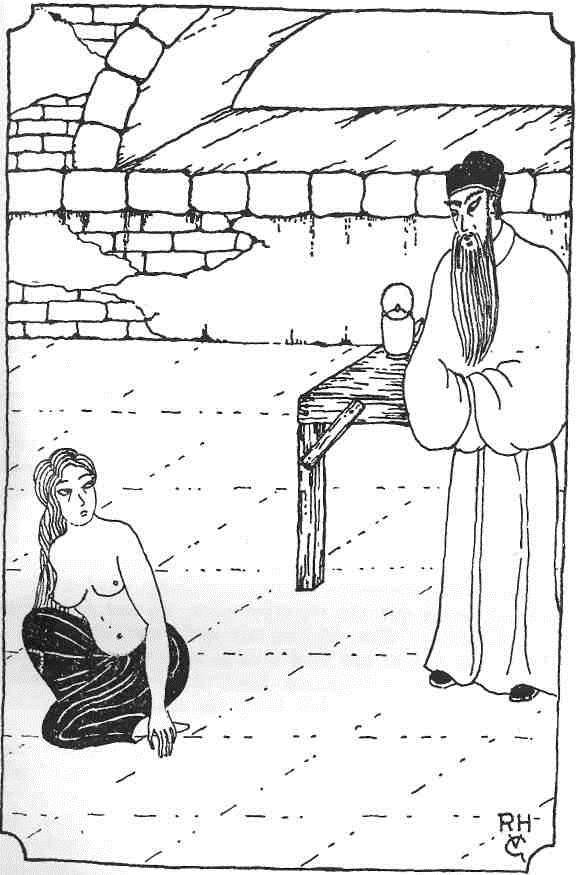

Suddenly the quilt was thrown to the floor. A half-naked girl with long, tousled hair jumped down from the plank-bed. After one look at the judge, she again made that strange, raucous sound and scuttled to the farthest corner. Then she dropped to her knees, trembling violently.

Judge Dee realized that he didn't present a very reassuring sight. He quickly pulled his identification document from his boot, unfolded it and walked up to the cowering girl, pointing with his forefinger at the large red stamp of the tribunal. Then he pointed at himself.

She apparently understood, for now she scrambled up and stared at him with large eyes that held an animal fear. She wore nothing but a tattered skirt, fastened to her waist with a piece of straw rope. She had a shapely, well-developed body and her skin was surprisingly white. Her round face was smeared with dirt but was not unattractive. Judge Dee pulled the bench up to the table and sat down. Feeling that some familiar gesture was needed to reassure the frightened girl, he took the teapot and drank from the spout, as farmers do.

The girl came up to the table, spat on the dirty top and drew in the spittle with her forefinger a few badly deformed characters. They read: 'Wang did not kill him.'

The judge nodded. He poured tea on the table-top, and motioned her to wipe it clean. She obediently went to the bed, took a rag and began to polish the table top with feverish haste. Judge Dee walked over to the stove and selected a few pieces of charcoal. Resuming his seat, he wrote with the charcoal on the table-top: 'Who killed him?'

THEN SHE DROPPED TO HER KNEES, TREMBLING VIOLENTLY

She shivered. She took the other piece of charcoal and wrote: 'Bad black goblins.' She pointed excitedly at the words, then scribbled quickly: 'Bad goblins changed the good rain spirit.'

'You saw the black goblins?' he wrote.

She shook her tousled head emphatically. She tapped with her forefinger repeatedly on the word 'black', then she pointed at her closed eyes and shook her head again. The judge sighed. He wrote: 'You know Mr Choong?'

She looked perplexedly at his writing, her finger in her mouth. He realized that the complicated character indicating the surname Choong was unknown to her. He crossed it out and wrote 'old man'.

She again shook her head. With an expression of disgust she drew circles round the words 'old man' and added: 'Too much blood. Good rain spirit won't come any more. No silver for Wang's boat any more.' Tears came trickling down her grubby cheeks as she wrote with a shaking hand: 'Good rain spirit always sleep with me.' She pointed at the plank-bed.

Judge Dee gave her a searching look. He knew that rain spirits played a prominent role in local folklore, so that it was only natural that they figured in the dreams and vagaries of this overdeveloped young girl. On the other hand, she had referred to silver. He wrote: 'What does the rain spirit look like?'

Her round face lit up. With a broad smile she wrote in big, clumsy letters: 'Tall. Handsome. Kind.' She drew a circle round each of the three words, then threw the charcoal on the table and, hugging her bare breasts, began to giggle ecstatically.

The judge averted his gaze. When he turned to look at her again, she had let her hands drop and stood there staring straight ahead with wide eyes. Suddenly her expression changed again. With a quick gesture she pointed at the arched window, and made some strange sounds. He turned round. There was a faint colour in the leaden sky, the trace of a rainbow. She stared at it, in childish delight, her mouth half open. The judge took up the piece of charcoal for one final question: 'When does the rain spirit come?'

She stared at the words for a long time, absentmindedly combing her long, greasy locks with her fingers. At last she bent over the table and wrote: 'Black night and much rain.' She put circles round the words 'black' and 'rain', then added: 'He came with the rain.'

All at once she put her hands to her face and began to sob convulsively. The sound mingled with the loud quacking of the ducks from below. Realizing that she couldn't hear the birds, he rose and laid his hand on her bare shoulder. When she looked up he was shocked by the wild, half-crazed gleam in her wide eyes. He quickly drew a duck on the table, and added the word 'hunger'.. She clasped her hand to her mouth and ran to the oven. Judge Dee scrutinized the large flagstones in front of the entrance. He saw there a clean space on the dirty, dust-covered floor. Evidently it was there that the dead man had lain, and the military police had swept up the floor. He remembered ruefully his unkind thoughts about them. Sounds of chopping made him turn round. The girl was cutting up stale rice cakes on a primitive chopping board. The judge watched with a worried frown her deft handling of the large kitchen knife. Suddenly she drove the long, sharp point of the knife in the board, then shook the chopped up rice cakes into the pan on the oven, giving the judge a happy smile over her shoulder. He nodded at her and went down the creaking stairs.

The rain had ceased, a thin mist was gathering over the marsh. While untying the reins, he told the noisy ducks: 'Don't worry, your breakfast is under way!'

He made his horse go ahead at a sedate pace. The mist came drifting in from the river. Strangely shaped clouds were floating over the tall reeds, here and there dissolving in long writhing trailers that resembled the tentacles of some monstrous water-animal. He wished he knew more about the hoary, deeply rooted beliefs of the local people. In many places people still venerated a river god or goddess, and fanners and fishermen made sacrificial offerings to these at the waterside. Evidently such things loomed large in the deaf-mute girl's feeble mind, shifting continually from fact to fiction, and unable to control the urges of her fullblown body. He drove his horse to a gallop.

Back at the North Gate, he told the corporal to take him to the pawnbroker's place. When they had arrived at the large, prosperous-looking pawnshop the corporal explained that Choong's private residence was located directly behind the shop and pointed at the narrow alleyway that led to the main entrance. Judge Dee told the corporal he could go back, and knocked on the black-lacquered gate.

A lean man, neatly dressed in a brown gown with black sash and borders, opened it. Bestowing a bewildered look on his wet, bearded visitor, he said: 'You want the shop, I suppose. I can take you, I was just going there.'

'I am the magistrate,' Judge Dee told him impatiently. 'I've just come from the marsh. Had a look at the place where your partner was murdered. Let's go inside, I want to hand over to you what was found on the dead body.'

Mr Lin made a very low bow and conducted his distinguished visitor to a small but comfortable side hall, furnished in conventional style with a few pieces of heavy blackwood furniture. He ceremoniously led the judge to the broad bench at the back. While his host was telling the old manservant to bring tea and cakes, the judge looked curiously at the large aviary of copper wire on the wall table. About a dozen paddy birds were fluttering around inside.

'A hobby of my partner's,' Mr Lin said with an indulgent smile. 'He was very fond of birds, always fed them himself.'

With his neatly trimmed chin-beard and small, greying moustache Lin seemed at first sight just a typical middle-class shopkeeper. But a closer inspection revealed deep lines around his thin mouth, and large, sombre eyes that suggested a man with a definite personality. The judge set his cup down and formally expressed his sympathy with the firm's loss. Then he took the envelope from his sleeve and shook out the visiting-cards, the small cash, the pawn-ticket and the two keys. 'That's all, Mr Lin. Did your partner as a rule carry large sums of money on him?'

Lin silently looked the small pile over, stroking his chin-beard.

'No, sir. Since he retired from the firm two years ago, there was no need for him to carry much money about. But he certainly had more on him than just these few coppers when he went out last night.'

'What time was that?'

'About eight, sir. After we had had dinner together here downstairs. He wanted to take a walk along the quay, so he said.'

'Did Mr Choong often do that?'

'Oh yes, sir! He had always been a man of solitary habits, and after the demise of his wife two years ago, he went out for long walks nearly every other night and always by himself. He always had his meals served in his small library upstairs, although I live here in this same house, in the left wing. Last night, however, there was a matter of business to discuss and therefore he came down to have dinner with me.'

'You have no family, Mr Lin?'

'No, sir. Never had time to establish a household! My partner had the capital, but the actual business of the pawnshop he left largely to me. And after his retirement he hardly set foot in our shop.'

'I see. To come back to last night. Did Mr Choong say when he would be back?'

'No, sir. The servant had standing orders not to wait up for him. My partner was an enthusiastic fisherman, you see. If he thought it looked like good fishing weather on the quay, he would hire a boat and pass the night up river.'

Judge Dee nodded slowly. 'The military police will have told you that they arrested a young fisherman called Wang San-lang. Did your partner often hire his boat?'

'That I don't know, sir. There are scores of fishermen about on the quay, you see, and most of them are eager to make a few extra coppers. But if my partner rented Wang's boat, it doesn't astonish me that he ran into trouble, for Wang is a violent young ruffian. I know of him, because being a fisherman of sorts myself, I have often heard the others talk about him. Surly, uncompanionable youngster.' He sighed. 'I'd like to go out fishing as often as my partner did, only I haven't got that much time... . Well, it's very kind of you to have brought these keys, sir. Lucky that Wang didn't take them and throw them away! The larger one is the key of my late partner's library, the other of the strongbox he has there for keeping important papers.' He stretched out his hand to take the keys, but Judge Dee scooped them up and put them in his sleeve.

'Since I am here,' he said, 'I shall have a look at Mr Choong's papers right now, Mr Lin. This is a murder case, and until it is solved, all the victim's papers are temporarily at the disposal of the authorities for possible clues. Take me to the library, please.'

'Certainly, sir.' Lin took the judge up a broad staircase and pointed at the door at the end of the corridor. The judge unlocked it with the larger key.

'Thanks very much, Mr Lin. I shall join you downstairs presently.'

The judge stepped into the small room, locked the door behind him, then went to push the low, broad window wide open. The roofs of the neighbouring houses gleamed in the grey mist. He turned and sat down in the capacious armchair behind the rosewood writing-desk facing the window. After a casual look at the iron-bound strongbox on the floor beside his chair, he leaned back and pensively took stock of his surroundings. The small library was scrupulously clean and furnished with simple, old-fashioned taste. The spotless whitewashed walls were decorated with two good landscape scrolls, and the solid ebony wall table bore a slender vase of white porcelain, with a few wilting roses. Piles of books in brocade covers were neatly stacked on the shelves of the small bookcase of spotted bamboo.

Folding his arms, the judge wondered what connection there could be between this tastefully arranged library that seemed to belong to an elegant scholar rather than to a pawnbroker, and the bare, dark room in the half-ruined watchtower, breathing decay, sloth and the direst poverty. After a while he shook his head, bent and unlocked the strongbox. Its contents matched the methodical neatness of the room: bundles of documents, each bound up with green ribbon and provided with an inscribed label. He selected the bundles marked 'private correspondence' and 'accounts and receipts'. The former contained a few important letters about capital investment and correspondence from his sons, mainly about their family affairs and asking Mr Choong's advice and instructions. Leafing through the second bundle, Judge Dee's practised eye saw at once that the deceased had been leading a frugal, nearly austere life. Suddenly he frowned. He had found a pink receipt, bearing the stamp of a house of assignation. It was dated back a year and a half. He quickly went through the bundle and found half a dozen similar receipts, the last dated back six months. Apparently Mr Choong had, after his wife's demise, hoped to find consolation in venal love, but had soon discovered that such hope was vain. With a sigh he opened the large envelope which he had taken from the bottom of the box. It was marked: 'Last Will and Testament'. It was dated one year before, and stated that all of Mr Choong's landed property — which was considerable — was to go to his two sons, together with two-thirds of his capital. The remaining one-third, and the pawnshop, was bequeathed to Mr Lin 'in recognition of his long and loyal service to the firm'.

The judge replaced the papers. He rose and went to inspect the bookcase. He discovered that except for two dog-eared dictionaries, all the books were collections of poetry, complete editions of the most representative lyrical poets of former times. He looked through one volume. Every difficult word had been annotated in red ink, in an unformed, rather clumsy hand. Nodding slowly, he replaced the volume. Yes, now he understood. Mr Choong had been engaged in a trade that forbade all personal feeling, namely that of a pawnbroker. And his pronouncedly ugly face made tender attachments unlikely. Yet at heart he was a romantic, hankering after the higher things of life, but very self-conscious and shy about these yearnings. As a merchant he had of course only received an elementary education, so he tried laboriously to expand his literary knowledge, reading old poetry with a dictionary in this small library which he kept so carefully locked.

Judge Dee sat down again and took his folding fan from his sleeve. Fanning himself, he concentrated his thoughts on this unusual pawnbroker. The only glimpse the outer world got of the sensitive nature of this man was his love of birds, evinced by the paddy birds downstairs. At last the judge got up. About to put his fan back into his sleeve, he suddenly checked himself. He looked at the fan absentmindedly for a while, then laid it on the desk. After a last look at the room he went downstairs.

His host offered him another cup of tea but Judge Dee shook his head. Handing Lin the two keys, he said, 'I have to go back to the tribunal now. I found nothing among your partner's papers suggesting that he had any enemies, so I think that this case is exactly what it seems, namely a case of murder for gain. To a poor man, three silver pieces are a fortune. Why are those birds fluttering about?' He went to the cage. 'Aha, their water is dirty. You ought to tell the servant to change it, Mr Lin.'

Lin muttered something and clapped his hands. Judge Dee groped in his sleeve. 'How careless of me!’ he exclaimed. 'I left my fan on the desk upstairs. Would you fetch it for me, Mr Lin?'

Just as Lin was rushing to the staircase, the old manservant came in. When the judge had told him that the water in the reservoir of the birdcage ought to be changed daily, the old man said, shaking his head, 'I told Mr Lin so, but he wouldn't listen. Doesn't care for birds. My master now, he loved them, he ...'

'Yes, Mr Lin told me that last night he had an argument with your master about those birds.'

'Well yes, sir, both of them got quite excited. What was it about, sir? I only caught a few words about birds when I brought the rice.'

'It doesn't matter,' the judge said quickly. He had heard Mr Lin come downstairs. 'Well, Mr Lin, thanks for the tea. Come to the chancery in, say, one hour, with the most important documents relating to your late partner's assets. My senior clerk will help you fill out the official forms, and the registration of Mr Choong's will.'

Mr Lin thanked the judge profusely and saw him respectfully to the door.

Judge Dee told the guards at the gate of the tribunal to return his rented horse to the blacksmith, and went straight to his private residence at the back of the chancery. The old housemaster informed him that Sergeant Hoong was waiting in his private office. The judge nodded. 'Tell the bathroom attendant that I want to take a bath now.'

In the black-tiled dressing-room adjoining the bath he quickly stripped off his robe, drenched with sweat and rain. He felt soiled, in body and in mind. The attendant sluiced him with cold water, and vigorously scrubbed his back. But it was only after the judge had been lying in the sunken pool in hot water for some time that he began to feel better. Thereafter he had the attendant massage his shoulders, and when he had been rubbed dry he put on a crisp clean robe of blue cotton, and placed a cap of thin black gauze on his head. In this attire he walked over to his women's quarters.

About to enter the garden room where his ladies usually passed the morning, he halted a moment, touched by the peaceful scene. His two wives, clad in flowered robes of thin silk, were sitting with Miss Tsao at the red-lacquered table in front of the open sliding doors. The walled-in rock garden outside, planted with ferns and tall, rustling bamboos, suggested refreshing coolness. This was his own private world, a clean haven of refuge from the outside world of cruel violence and repulsive decadence he had to deal with in his official life. Then and there he took the firm resolution that he would preserve his harmonious family life intact, always.

His First Lady put her embroidery frame down and quickly came to meet him. 'We have been waiting with breakfast for you for nearly an hour!’ she told him reproachfully.

'I am sorry. The fact is that there was some trouble at the North Gate and I had to attend to it at once. I must go to the chancery now, but I shall join you for the noon rice.' She conducted him to the door. When she was making her bow he told her in a low voice, 'By the way, I have decided to follow your advice in the matter we discussed last night. Please make the necessary arrangements.'

With a pleased smile she bowed again, and the judge went down the corridor that led to the chancery.

He found Sergeant Hoong sitting in an armchair in the corner of his private office. His old adviser got up and wished him a good morning. Tapping the document in his hand, the sergeant said, 'I was relieved when I got this report, Your Honour, for we were getting worried about your prolonged absence! I had the prisoner locked up in jail, and the dead body deposited in the mortuary. After I had viewed it with the coroner, Ma Joong and Chiao Tai, your two lieutenants, rode to the North Gate to see whether you needed any assistance.'

Judge Dee had sat down behind his desk. He looked askance at the pile of dossiers. 'Is there anything urgent among the incoming documents, Hoong?'

'No, sir. All those files concern routine administrative matters.'

'Good. Then we shall devote the noon session to the murder of the pawnbroker Choong.'

The sergeant nodded contentedly. 'I saw from the captain's report, Your Honour, that it is a fairly simple case. And since we have the murder suspect safely under lock and key ...'

The judge shook his head. 'No, Hoong, I wouldn't call it a simple case, exactly. But thanks to the quick measures of the military police, and thanks to the lucky chance that brought me right into the middle of things, a definite pattern has emerged.'

He clapped his hands. When the headman came inside and made his bow the judge ordered him to bring the prisoner Wang before him. He went on to the sergeant, 'I am perfectly aware, Hoong, that a judge is supposed to interrogate an accused only publicly, in court. But this is not a formal hearing. A general talk for my orientation, rather.'

Sergeant Hoong looked doubtful, but the judge vouchsafed no further explanation, and began to leaf through the topmost file on his desk. He looked up when the headman brought Wang inside. The chains had been taken off him, but his swarthy face looked as surly as before. The headman pressed him down on his knees, then stood himself behind him, his heavy whip in his hands.

'Your presence is not required, Headman,' Judge Dee told him curtly.

The headman cast a worried glance at Sergeant Hoong. 'This is a violent ruffian, Your Honour,' he began diffidently. 'He might ...'

'You heard me!’ the judge snapped.

After the disconcerted headman had left, Judge Dee leaned back in his chair. He asked the young fisherman in a conversational tone, 'How long have you been living on the waterfront, Wang?'

'Ever since I can remember,' the boy muttered.

'It's a strange land,' the judge said slowly to Sergeant Hoong. 'When I was riding through the marsh this morning, I saw weirdly shaped clouds drifting about, and shreds of mist that looked like long arms reaching up out of the water, as if ...'

The youngster had been listening intently. Now he interrupted quickly: 'Better not speak of those things!'

'Yes, you know all about those things, Wang. On stormy nights, there must be more going on in the marshlands than we city-dwellers realize.'

Wang nodded vigorously. 'I've seen many things,' he said in a low voice, 'with my own eyes. They all come up from the water. Some can harm you, others help drowning people, sometimes. But it's better to keep away from them, anyway.'

'Exactly! Yet you made bold to interfere, Wang. And see what has happened to you now! You were arrested, you were kicked and beaten, and now you are a prisoner accused of murder!'

'I told you I didn't kill him!'

'Yes. But did you know who or what killed him? Yet you stabbed him when he was dead. Several times.'

'I saw red ...' Wang muttered. 'If I'd known sooner, I'd have cut his throat. For I know him by sight, the rat, the ...'

'Hold your tongue!’ Judge Dee interrupted him sharply. 'You cut up a dead man, and that's a mean and cowardly thing to do!’ He continued, calmer, 'However, since even in your blind rage you spared Oriole by refraining from an explanation, I am willing to forget what you did. How long have you been going with her?'

'Over a year. She's sweet, and she's clever too. Don't believe she's a half-wit! She can write more than a hundred characters. I can read only a dozen or so.'

Judge Dee took the three silver pieces from his sleeve and laid them on the desk. 'Take this silver, it belongs rightly to her and to you. Buy your boat and marry her. She needs you, Wang.' The youngster snatched the silver and tucked it in his belt. The judge went on, 'You'll have to go back to jail for a few hours, for I can't release you until you have been formally cleared of the murder charge. Then you'll be set free. Learn to control your temper, Wang!'

He clapped his hands. The headman came in at once. He had been waiting just outside the door, ready to rush inside at the first sign of trouble.

'Take the prisoner back to his cell, headman. Then fetch Mr Lin. You'll find him in the chancery.'

Sergeant Hoong had been listening with mounting astonishment. Now he asked with a perplexed look, 'What were you talking about with that young fellow, Your Honour? I couldn't follow it at all. Are you really intending to let him go?'

Judge Dee rose and went to the window. Looking out at the dreary, wet courtyard, he said, 'It's raining again! What was I talking about, Hoong? I was just checking whether Wang really believed all those weird superstitions. One of these days, Hoong, you might try to find in our chancery library a book on local folklore.'

'But you don't believe all that nonsense, sir!'

'No, I don't. Not all of it, at least. But I feel I ought to read up on the subject, for it plays a large role in the daily life of the common people of our district. Pour me a cup of tea, will you?'

While the sergeant prepared the tea, Judge Dee resumed his seat and concentrated on the official documents on his desk. After he had drunk a second cup, there was a knock at the door. The headman ushered Mr Lin inside, then discreetly withdrew.

'Sit down, Mr Lin!’ the judge addressed his guest affably. 'I trust my senior clerk gave you the necessary instructions for the documents to be drawn up?'

'Yes, indeed,. Your Honour. Right now we were checking the landed property with the register and ...'

According to the will drawn up a year ago,' the judge cut in, 'Mr Choong bequeathed all the land to his two sons, together with two-thirds of his capital, as you know. One-third of the capital, and the pawnshop, he left to you. Are you planning to continue the business?'

'No, sir,' Lin replied with his thin smile. 'I have worked in that pawnshop for more than thirty years, from morning till night. I shall sell it, and live off the rent from my capital.'

'Precisely. But suppose Mr Choong had made a new will? Containing a new clause stipulating that you were to get only the shop?' As Lin's face went livid, he went on quickly, 'It's a prosperous business, but it would take you four or five years to assemble enough capital to retire. And you are getting on in years, Mr Lin.'

'Impossible! How ... how could he ...' Lin stammered. Then he snapped, 'Did you find a new will in his strongbox?'

Instead of answering the question, Judge Dee said coldly: 'Your partner had a mistress, Mr Lin. Her love came to mean more to him than anything else.'

Lin jumped up. 'Do you mean to say that the old fool willed his money to that deaf-mute slut?'

'Yes, you know all about that affair, Mr Lin. Since last night, when your partner told you. You had a violent quarrel. No, don't try to deny it! Your manservant overheard what you said, and he will testify in court.'

Lin sat down again. He wiped his moist face. Then he began, calmer now, 'Yes, sir, I admit that I got very angry when my partner informed me last night that he loved that girl. He wanted to take her away to some distant place and marry her. I tried to make him see how utterly foolish that would be, but he told me to mind my own business and ran out of the house in a huff. I had no idea he would go to the tower. It's common knowledge that that young hoodlum Wang is carrying on with the half-wit. Wang surprised the two, and he murdered my partner. I apologize for not having mentioned these facts to you this morning, sir. I couldn't bring myself to compromise my late partner... . And since you had arrested the murderer, everything would have come out anyway in court... .' He shook his head. 'I am partly to blame, sir. I should have gone after him last night, I should've ...'

'But you did go after him, Mr Lin,' Judge Dee interrupted curtly. 'You are a fisherman too, you know the marsh as well as your partner. Ordinarily one can't cross the marsh, but after a heavy rain the water rises, and an experienced boatman in a shallow skiff could paddle across by way of the swollen gullies and pools.'

'Impossible! The road is patrolled by the military police all night!'

'A man crouching in a skiff could take cover behind the tall reeds, Mr Lin. Therefore your partner could only visit the tower on nights after a heavy rain. And therefore the poor half-witted girl took the visitor for a supernatural being, a rain spirit. For he came with the rain.' He sighed. Suddenly he fixed Lin with his piercing eyes and said sternly, 'When Mr Choong told you about his plans last night, Lin, you saw all your long-cherished hopes of a life in ease and luxury go up into thin air. Therefore you followed Choong, and you murdered him in the tower by thrusting a knife into his back.'

Lin raised his hands. 'What a fantastic theory, sir! How do you propose to prove this slanderous accusation?'

'By Mrs Pei's pawn-ticket, among other things. It was found by the military police on the scene of the crime. But Mr Choong had completely retired from the business, as you told me yourself. Why then would he be carrying a pawn-ticket that had been issued that very day?' As Lin remained silent, Judge Dee went on, 'You decided on the spur of the moment to murder Choong, and you rushed after him. It was the hour after the evening rice, so the shopkeepers in your neighbourhood were on the lookout for their evening custom when you passed. Also on the quay, where you took off in your small skiff, there were an unusual number of people about, because it looked like heavy rain was on its way.' The glint of sudden panic in Lin's eyes was the last confirmation the judge had been waiting for. He concluded in an even voice, 'If you confess now, Mr Lin, sparing me the trouble of sifting out all the evidence of the eyewitnesses, I am prepared to add a plea for clemency to your death sentence, on the ground that it was unpremeditated murder.'

Lin stared ahead with a vacant look. All at once his pale face became distorted by a spasm of rage. 'The despicable old lecher!’ he spat. 'Made me sweat and slave all those years ... and now he was going to throw all that good money away on a cheap, half-witted slut! The money I made for him... .' He looked steadily at the judge as he added in a firm voice, 'Yes, I killed him. He deserved it.'

Judge Dee gave the sergeant a sign. While Hoong went to the door the judge told the pawnbroker, 'I shall hear your full confession during the noon session.'

They waited in silence till the sergeant came back with the headman and two constables. They put Lin in chains and led him away.

A sordid case, sir,' Sergeant Hoong remarked dejectedly.

The judge took a sip from his teacup and held it up to be refilled. 'Pathetic, rather. I would even call Lin pathetic, Hoong, were it not for the fact that he made a determined effort to incriminate Wang.'

'What was Wang's role in all this, sir? You didn't even ask him what he did this morning!'

'There was no need to, for what happened is as plain as a pikestaff. Oriole had told Wang that a rain spirit visited her at night and sometimes gave her money. Wang considered it a great honour that she had relations with a rain spirit. Remember that only half a century ago in many of the river districts in our Empire the people immolated every year a young boy or girl as a human sacrifice to the local river god — until the authorities stepped in. When Wang came to the tower this morning to bring Oriole her fish, he found in her room a dead man lying on his face on the floor. The crying Oriole gave him to understand that goblins had killed the rain spirit and changed him into an ugly old man. When Wang turned over the corpse and recognized the old man, he suddenly understood that he and Oriole had been deceived, and in a blind rage pulled his knife and stabbed the dead man. Then he realized that this was a murder case and he would be suspected. So he fled. The military police caught him while trying to wash his trousers which had become stained with Choong's blood.'

Sergeant Hoong nodded. 'How did you discover all this in only a few hours, sir?'

'At first I thought the captain's theory hit the nail on the head. The only point which worried me a bit was the long interval between the murder and the stabbing of the victim's breast. I didn't worry a bit about the pawn-ticket, for it is perfectly normal for a pawnbroker to carry a ticket about that he has made out that very same day. Then, when questioning Wang, it struck me that he called Choong a crook. That was a slip of the tongue, for Wang was determined to keep both Oriole and himself out of this, so as not to have to divulge that they had let themselves be fooled. While I was interviewing Oriole she stated that the "goblins" had killed and changed her rain spirit. I didn't understand that at all. It was during my visit to Lin that at last I got on the right track. Lin was nervous and therefore garrulous, and told me at length about his partner taking no part at all in the business. I remembered the pawn-ticket found on the murder scene, and began to suspect Lin. But it was only after I had inspected the dead man's library and got a clear impression of his personality that I found the solution. I checked my theory by eliciting from the manservant the fact that Lin and Choong had quarreled about Oriole the night before. The name Oriole meant of course nothing to the servant, but he told me they had a heated argument about birds. The rest was routine.'

The judge put his cup down. 'I have learned from this case how important it is to study carefully our ancient handbooks of detection, Hoong. There it is stated again and again that the first step of a murder investigation is to ascertain the character, daily life and habits of the victim. And in this case it was indeed the murdered man's personality that supplied the key.'

Sergeant Hoong stroked his grey moustache with a pleased smile. That girl and her young man were very lucky indeed in having you as the investigating magistrate, sir! For all the evidence pointed straight at Wang, and he would have been convicted and beheaded. For the girl is a deaf-mute, and Wang isn't much of a talker either!'

Judge Dee nodded. Leaning back in his chair, he said with a faint smile:

'That brings me to the main benefit I derived from this case, Hoong. A very personal and very important benefit. I must confess to you that early this morning I was feeling a bit low, and for a moment actually doubted whether this was after all the right career for me. I was a fool. This is a great, a magnificent office, Hoong! If only because it enables us to speak for those who can't speak for themselves.'

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ