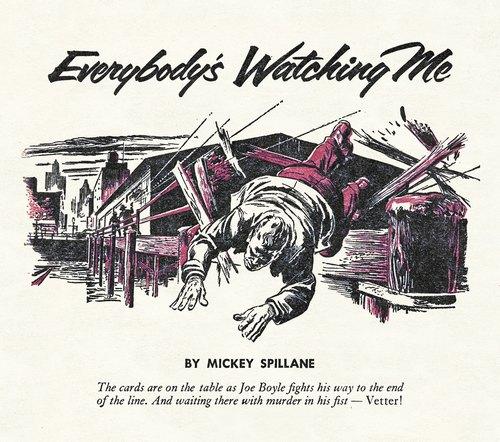

Everybody’s Watching Me by Mickey Spillane

The cards are on the table as Joe Boyle fights his way to the end of the line. And waiting there with murder in his fist — Vetter!

Part IV

What has happened before: When young Joe Boyle is paid to deliver a note reading “Cooley is dead. Now my fine fat louse, I’m going to spill your guts all over your own floor,” and signed Vetter, he finds himself in the middle of a murderous rat race. Vetter is a mysterious killer believed to be a friend of Cooley, unknown otherwise except for the fact that he’s responsible for the death of many hoodlums. Renzo, recipient of the note, local big-time racketeer, has Joe beaten and then tailed in an effort to locate Vetter. Phil Carboy, a rival racketeer, learning Vetter is in town, pays Joe to finger Vetter the next time he appears. Even the police in the form of Detective Sergeant Gonzales, want Vetter. From Вuску Edwards, Joe’s newspaperman friend, and from Captain Gerot of the police, Joe pieces together the theory that Cooley may have been rubbed for narcotic connections or because he knew too much about the local gang setup. Helen Troy, featured dancer at Renzo’s club, befriends Joe. Falling in love with her, he gives her money to leave Renzo and then goes to beep a rendezvous with a stranger who tells him that Cooley was billed because he knew the boys were slipping in drugs through a new door, and stole a $4,000,000 shipment from them. Joe calls Gonzales to tell him Carboy paid him big money to finger Vetter, and that Carboy’s men are now tailing Joe. He gets Jack Cooley’s last address from Bucky Edwards, dodges Carboy’s tails and goes to Cooley’s rooming house. He learns that the dead man used to go fishing often, using a place called Gulley’s for his meetings with other men. Joe calls Gerot to learn, that Helen has been shot at and is now missing. Outside his house, he meets the stranger again, and the stranger kills one of Joe s tails. Joe runs back to his room, finds Helen there. She d been waiting for a train when the shots came at her. Acting on a tip from the stranger, Joe asks Helen what her connection with the dead Cooley was. She tells him Cooley was blackmailing Renzo. She also tells him that Cooley left a quarter pound of heroin with her — which she threw down a sewer. Joe feels he is now ready to go out and wind up the whole thing.

I woke up just past noon. Helen was still asleep, restlessly tossing in some dream. The sheet had slipped down to her waist, and everytime she moved, her body rippled with sinuous grace. I stood looking at her for a long time, my eyes devouring her, every muscle in my body wanting her. There were other things to do, and I cursed those other things and set out to do them.

When I knew the landlady was gone I made a trip downstairs to her ice box and lifted enough for a quick meal. I had to wake Helen up to eat, then sat back with an old magazine to let the rest of the day pass by. At seven we made the first move. It was a nice simple little thing that put the whole neighborhood in an uproar for a half hour but gave us a chance to get out without being spotted.

All I did was call the fire department and tell them there was a gas leak in one of the tenements. They did the rest. Besides holding everybody back from the area they evacuated a whole row of houses, including us and while they were trying to run down the false alarm we grabbed a cab and got out.

Helen asked, “Where to?”

“A place called Gulley’s. It’s a stop for the fishing boats. You know it?”

“I know it.” She leaned back against the cushions. “It’s a tough place to be. Jack took me out there a couple of times.”

“He did? Why?”

“Oh, we ate, then he met some friends of his. We were there when the place was raided. Gulley was selling liquor after closing hours. Good thing Jack had a friend on the force.”

“Who was that?”

“Some detective with a Mexican name.”

“Gonzales,” I said.

She looked at me. “That’s right.” She frowned slightly. “I didn’t like him at all.”

That was a new angle. One that didn’t fit in. Jack with a friend on the force. I handed Helen a cigarette, lit it and sat back with mine.

It took a good hour to reach the place and at first glance it didn’t seem worth the ride. From the highway the road weaved out onto a sand spit and in the shadows you could see the parked cars and occasionally couples in them. Here and there along the road the lights of the car picked up the glint of beer cans and empty bottles. I gave the cabbie an extra five and told him to wait and when we went down the gravel path, he pulled it under the trees and switched off his lights.

Gulley’s was a huge shack built on the sand with a porch extending out over the water. There wasn’t a speck of paint on the weather-racked framework and over the whole place the smell of fish hung like a blanket. It looked like a creep joint until you turned the corner and got a peek at the nice modern dock setup he had and the new addition on the side that probably made the place the yacht club’s slumming section. If it didn’t have anything else it had atmosphere. We were right on the tip of the peninsular that jutted out from the mainland and like the sign said, it was the last chance for the boats to fill up with the bottled stuff before heading out to deep water.

I told Helen to stick in the shadows of the hedge row that ran around the place while I took a look around, and though she didn’t like it, she melted back into the brush. I could see a couple of figures on the porch, but they were talking too low for me to hear what was going on. Behind the bar that ran across the main room inside, a flat-faced fat guy leaned over reading the paper with his ears pinned inside a headset. Twice he reached back, frowning and fiddled with a radio under the counter. When the phone rang he scowled again, slipped off the headset and said, “Gulley speaking. Yeah. Okay. So-long.”

When he went back to his paper I crouched down under the rows of windows and eased around the side. The sand was a thick carpet that silenced all noise and the gentle lapping of the water against the docks covered any other racket I could make. I was glad to have it that way too. There were guys spotted around the place that you couldn’t see until you looked hard and they were just lounging. Two were by the building and the other two at the foot of the docks, edgy birds who lit occasional cigarettes and shifted around as they smoked them. One of them said something and a pair of them swung around to watch the twin beams of a car coming up the highway. I looked too, saw them turn in a long arc then cut straight for the shack.

One of the boys started walking my way, his feet squeaking in the dry sand. I dropped back around the corner of the building, watched while he pulled a bottle out from under the brush, then started back the way I had come.

The car door slammed. A pair of voices mixed in an argument and another one cut them off. When I heard it I could feel my lips peel back and I knew that if I had a knife in my fist and Mark Renzo passed by me in the dark, whatever he had for supper would spill all over the ground. There was another voice, swearing at something. Johnny. Nice, gentle Johnny who was going to cripple me for life.

I wasn’t worrying about Helen because she wouldn’t be sticking her neck out. I was hoping hard that my cabbie wasn’t reading any paper by his dome light and when I heard the boys reach the porch and go in, I let my breath out hardly realizing that my chest hurt from holding it in so long.

You could hear their hellos from inside, muffled sounds that were barely audible. I had maybe a minute to do what I had to do and didn’t waste any time doing it. I scuttled back under the window that was at one end of the bar, had time to see Gulley shaking hands with Renzo over by the door, watched him close and lock it and while they were still far enough away not to notice the movement, slid the window up an inch and flattened against the wall.

They did what I expected they’d do. I heard Gulley invite them to the bar for a drink and set out the glasses. Renzo said, “Good stuff.”

“Only the best. You know that.”

Johnny said, “Sure. You treat your best customers right.”

Bottle and glasses clinked again for another round. Then the headset that was under the bar started clicking. I took a quick look, watched Gulley pick it up, slap one earpiece against his head and jot something down on a pad.

Renzo said, “She getting in without trouble?”

Gulley set the headset down and leaned across the bar. He looked soft, but he’d been around a long time and not even Renzo was playing any games with him. “Look,” he said, “You got your end of the racket. Keep out of mine. You know?”

“Getting tough, Gulley?”

I could almost hear Gulley smile. “Yeah. Yeah, in case you want to know. You damn well better blow off to them city lads, not me.”

“Ease off,” Renzo told him. He didn’t sound rough any more. “Heard a load was due in tonight.”

“You hear too damn much.”

“It didn’t come easy. I put out a bundle for the information. You know why?” Gulley didn’t say anything. Renzo said, “I’ll tell you why. I need that stuff. You know why?”

“Tough. Too bad. You know. What you want is already paid for and is being delivered. You ought to get your head out of your whoosis.”

“Gulley...” Johnny said really quiet. “We ain’t kidding. We need that stuff. The big boys are getting jumpy. They think we pulled a fast one. They don’t like it. They don’t like it so bad maybe they’ll send a crew down here to straighten everything out and you may get straightened too.”

Inside Gulley’s feet were nervous on the floorboards. He passed in front of me once, his hands busy wiping glasses. “You guys are nuts. Carboy paid for this load. So I should stand in the middle?”

“Maybe it’s better than standing in front of us,” Johnny said.

“You got rocks. Phil’s out of the local stuff now. He’s got a pretty big outfit.”

“Just peanuts, Gulley, just peanuts.”

“Not any more. He’s moving in since you dumped the big deal.”

Gulley’s feet stopped moving. His voice had a whisper in it. “So you were big once. Now I see you sliding. The big boys are going for bargains and they don’t like who can’t deliver, especially when it’s been paid for. That was one big load. It was special. So you dumped it. Phil’s smart enough to pick it up from there and now he may be top dog. I’m not in the middle. Not without an answer to Phil and he’ll need a good one.”

“Vetter s in town, Gulley!” Renzo almost spat the word out. “You know how he is? He ain’t a gang you bust up. He’s got a nasty habit of killing people. Like always, he’s moving in. So we pay you for the stuff and deliver what we lost. We make it look good and you tell Phil it was Vetter. He’ll believe that.”

I could hear Gulley breathing hard. “Jerks, you guys,” he said. There was a hiss in his words. “I should string it on Vetter. Man, you’re plain nuts. I seen that guy operate before. Who the hell you think edged into that Frisco deal? Who got Morgan in El Paso while he was packing a half a million in cash and another half in powder. So a chowderhead hauls him in to cream some local fish and the guy walks awav with the town. Who the hell is that guy?”

Johnny’s laugh was bitter. Sharp. Gulley had said it all and it was like a knife sticking in and being twisted. “I’d like to meet him. Seems like he was a buddy of Jack Cooley. You remember Jack Cooley, Gulley? You were in on that. Cooley got off with your kick too. Maybe Vetter would like to know about that.”

“Shut up.”

“Not yet. We got business to talk about.”

Gulley seemed out of breath. “Business be damned. I ain’t tangling with Vetter.”

“Scared?”

“Damn right, and so are you. So’s everybody else.”

“Okay,” Johnny said. “So for one guy or a couple he’s trouble. In a big town he can make his play and move fast. Thing is with enough guys in a burg like this he can get nailed.”

“And how many guys get nailed with him. He’s no dope. Who you trying to smoke?”

“Nuts, who cares who gets nailed as long as it ain’t your own bunch. You think Phil Carboy’ll go easy if he thinks Vetter jacked a load out from under him? Like you told us, Phil’s an up and coming guy. He’s growing. He figures on being the top kick around here and let Vetter give him the business and he goes all out to get the guy. So two birds are killed. Vetter and Carboy. Even if Carboy gets him, his load’s gone. He’s small peanuts again.”

“Where does that get me?” Gulley asked.

“I was coming to that. You make yours. The percentage goes up ten. Good?”

Gulley must have been thinking greedy. He started moving again, his feet coming closer. He said, “You talk big. Where’s the cabbage?”

“I got it on me,” Renzo said.

“You know what Phil was paying for the junk?”

“The word said two million.”

“It’s gonna cost to take care of the boys on the boat.”

“Not so much.” Renzo’s laugh had no humor in it. “They talk and either Carbov’ll finish ’em or Vetter will. They stay shut up for free.”

“How much for me?” Gulley asked.

“One hundred thousand for swinging the deal, plus the extra percentage. You think it’s worth it?”

“I’ll go it,” Gulley said.

Nobody spoke for a second, then Gulley said, “I’ll phone the boat to pull into the slipside docks. They can unload there. The stuff is packed in beer cans. It won’t make a big package so look around for it. They’ll probably shove it under one of the benches.”

“Who gets the dough?”

“You row out to the last boat mooring. The thing is red with a white stripe around it. Unscrew the top and drop it in.”

“Same as the way we used to work it?”

“Right. The boys on the boat won’t like going in the harbor and they’ll be plenty careful, so don’t stick around to lift the dough and the stuff too. That ’breed on the ship got a lockerfull of chatter guns he likes to hand out to his crew.”

“It’ll get played straight.”

“I’m just telling you.”

Renzo said, “What do you tell Phil?”

“You kidding? I don’t say nothing. All I know is I lose contact with the boat. Next the word goes that Vetter is mixed up in it. I don’t say nothing.” He paused for a few seconds, his breath whistling in his throat, then, “But don’t forget something... You take Carboy for a sucker and maybe even Vetter. Lay off me. I keep myself covered. Anything happens to me and the next day the cops get a letter naming names. Don’t ever forget that.”

Renzo must have wanted to say something. He didn’t. Instead he rasped, “Go get the cash for this guy.”

Somebody said, “Sure, boss,” and walked across the room. I heard the lock snick open, then the door.

“This better work,” Renzo said. He fiddled with his glass a while. “I’d sure like to know what that punk did with the other stuff.”

“He ain’t gonna sell it, that’s for sure,” Johnny told him. “You think maybe Cooley and Vetter were in business together.”

“I’m thinking maybe Cooley was in business with a lot of people. That lousy blonde. When I get her she’ll talk plenty. I should’ve kept my damn eyes open.”

“I tried to tell you, boss.”

“Shut up,” Renzo said. “You just see that she gets found.”

I didn’t wait to hear any more. I got down in the darkness and headed back to the path. Overhead the sky was starting to lighten as the moon came up, a red circle that did funny things to the night and started the long fingers of shadows drifting out from the scraggly brush. The trees seemed to be ponderous things that reached down with sharp claws, feeling around in the breeze for something to grab. I found the place where I had left Helen, found a couple of pebbles and tossed them back into the brush. I heard her gasp, then whispered her name.

She came forward silently, said, “Joe?” in a hushed tone.

“Yeah. Let’s get out of here.”

“What happened?”

“Later. I’ll start back to the cab to make sure it’s clear. If you don’t hear anything, follow me. Got it?”

“... yes.” She was hesitant and I couldn’t blame her. I got off the gravel path into the sand, took it easy and tried to search out the shadows. I reached the clearing, stood there until I was sure the place was empty then hopped over to the cab.

I had to shake the driver awake and he came out of it stupidly. “Look, keep your lights off going back until you’re on the highway, then keep ’em on low. There’s enough moon to see by.”

“Hey... I don’t want trouble.”

“You’ll get it unless you do what I tell you.”

“Well... okay.”

“A dame’s coming out in a minute. Soon as she comes start it up and try to keep it quiet.”

I didn’t have long to wait. I heard her feet on the gravel, walking fast but not hurrying. Then I heard something else that froze me a second. A long, low whistle of appreciation like the kind any blonde’ll get from the pool hall boys. I hopped in the cab, held the door open. “Let’s go, feller,” I said.

As soon as the engine ticked over Helen started to run. I yanked her inside as the car started moving and kept down under the windows. She said, “Somebody...”

“I heard it.”

“I didn’t see who it was.”

“Maybe it’ll pass. Enough cars come out here to park.”

Her hand was tight in mine, the nails biting into my palm. She was half-turned on the seat, her dress pulled back over the glossy knees of her nylons, her breasts pressed against my arm. She stayed that way until we reached the highway then little by little eased up until she was sitting back against the cushions. I tapped my forefinger against my lips then pointed to the driver. Helen nodded, smiled, then squeezed my hand again. This time it was different. The squeeze went with the smile.

I paid off the driver at the edge of town. He got more than the meter said, a lot more. It was big enough to keep a man’s mouth shut long enough to get him in trouble when he opened it too late. When he was out of sight we walked until we found another cab, told the driver to get us to a small hotel someplace, and the usual leer and blonde inspection muttered the name of a joint and pulled away from the curb.

It was the kind of a place where they don’t ask questions and don’t believe what you write in the register anyway. I signed Mr. and Mrs. Valiscivitch, paid the bill in advance for a week and when the clerk read the name I got a screwy look because the name was too screwballed to be anything but real to him. Maybe he figured his clientele was changing. When we got to the room I said, “You park here for a few days.”

“Are you going to tell me anything?”

“Should I?”

“You’re strange, Joe. A very strange boy.”

“Stop calling me a boy.”

Her face got all beautiful again and when she smiled there was a real grin in it. She stood there with her hands on her hips and her feet apart like she was going into some part of her routine and I could feel my body starting to burn at the sight of her. She could do things with herself by just breathing and she did them, the smile and her eyes getting deeper all the time. She saw what was happening to me and said, “You’re not such a boy after all.” She held out her hand and I took it, pulling her in close. “The first time you were a boy. All bloody, dirt ground into your face. When Renzo tore you apart I could have killed him. Nobody should do that to another one, especially a boy. But then there was Johnny and you seemed to grow up. I’ll never forget what you did to him.”

“He would have hurt you.”

“You’re even older now. Or should I say matured? I think you finished growing up last night, Joe, last night... with me. I saw you grow up, and I only hope I haven’t hurt you in the process. I never was much good for anybody. That’s why I left home, I guess. Everyone I was near seemed to get hurt. Even me.”

“You’re better than they are, Helen. The breaks were against you, that’s all.”

“Joe... do you know you’re the first one who did anything nice for me without wanting... something?”

“Helen...”

“No, don’t say anything. Just take a good look at me. See everything that I am? It shows. I know it shows. I was a lot of things that weren’t nice. I’m the kind men want but who won’t introduce to their families. I’m a beautiful piece of dirt, Joe.” Her eyes were wet. I wanted to brush away the wetness but she wouldn’t let my hands go. “You see what I’m telling you? You’re young... don’t brush up against me too close. You’ll get dirty and you’ll get hurt.”

She tried to hide the sob in her throat but couldn’t. It came up anyway and I made her let my hands go and when she did I wrapped them around her and held her tight against me. “Helen,” I said. “Helen...”

She looked at me, grinned weakly. “We must make a funny pair,” she said. “Run for it, Joe. Don’t stay around any longer.”

When I didn’t answer right away her eyes looked at mine. I could see her starting to frown a little bit and the curious bewilderment crept across her face. Her mouth was red and moist, poised as if she were going to ask a question, but had forgotten what it was she wanted to say. I let her look and look and look and when she shook her head in a minute gesture of puzzlement I said, “Helen... I’ve rubbed against you. No dirt came off. Maybe it’s because I’m no better than you think you are.”

“Joe...”

“It never happened to me before, kid. When it happens I sure pick a good one for it to happen with.” I ran my fingers through her hair. It was nice looking at her like that. Not down, not up, but right into her eyes. “I don’t have any family to introduce you to, but if I had, I would. Yellow head, don’t worry about me getting hurt.”

Her eyes were wide now as if she had the answer. She wasn’t believing what she saw.

“I love you, Helen. It’s not the way a boy would love anybody. It’s a peculiar kind of thing I never want to change.”

“Joe...”

“But it’s yours now. You have to decide. Look at me, kid. Then say it.”

Those lovely wide eyes grew misty again and the smile came back slowly. It was a warm, radiant smile that told me more than her words. “It can happen to us, can’t it? Perhaps it’s happened before to somebody else, but it can happen to us, can’t it? Joe... It seems so... I can’t describe it. There’s something...”

“Say it out.”

“I love you, Joe. Maybe it’s better that I should love a little boy. Twenty... twenty-one you said? Oh, please, please don’t let it be wrong, please...” She pressed herself to me with a deep-throated sob and clung there. My fingers rubbed her neck, ran across the width of her shoulders then I pushed her away. I was grinning a little bit now.

“In eighty years it won’t make much difference,” I said. Then what else I had to say her mouth cut off like a burning torch that tried to seek out the answer and when it was over it didn’t seem important enough to mention anyway.

I pushed her away gently. “Now, listen, there isn’t much time. I want you to stay here. Don’t go out at all and if you want anything, have it sent up. When I come back, I’ll knock once. Just once. Keep that door locked and stay out of sight. You got that?”

“Yes, but...”

“Don’t worry about me. I won’t be long. Just remember to make sure it’s me and nobody else.” I grinned at her. “You aren’t getting away from me any more, blondie. Now it’s the two of us for keeps, together.”

“All right, Joe.”

I nudged her chin with my fist, held her face up and kissed it. That curious look was back and she was trying to think of something again. I grinned, winked at her and got out before she could keep me. I even grinned at the clerk downstairs, but he didn’t grin back. He probably thought anybody who’d leave a blonde like that alone was nuts or married and he wasn’t used to it.

But it sure felt good. You know how. You feel so good you want to tear something apart or laugh and maybe a little crazy, but that’s all part of it. That’s how I was feeling until I remembered the other things and knew what I had to do.

I found a gin mill down the street and changed a buck into a handful of coins. Three of them got my party and I said, “Mr. Carboy?”

“That’s right. Who is this?”

“Joe Boyle.”

Carboy told somebody to be quiet then, “What do you want, kid?”

I got the pitch as soon as I caught the tone in his voice. “Your boys haven’t got me, if that’s what you’re thinking,” I told him.

“Yeah?”

“I didn’t take a powder. I was trying to get something done. For once figure somebody else got brains too.”

“You weren’t supposed to do any thinking, kid.”

“Well, if I don’t, you lose a boatload of merchandise, friend.”

“What?” It was a whisper that barely came through.

“Renzo’s ticking you off. He and Gulley are pulling a switch. Your stuff gets delivered to him.”

“Knock it off, kid. What do you know?”

“I know the boat’s coming into the slipside docks with the load and Renzo will be picking it up. You hold the bag, brother.”

“Joe,” he said. “You know what happens if you’re queering me.”

“I know.”

“Where’d you pick it up?”

“Let’s say I sat in on Renzo’s conference with Gulley.”

“Okay, boy. I’ll stick with it. You better be right. Hold on.” He turned away from the phone and shouted muffled orders at someone. There were more muffled shouts in the background then he got back on the line again. “Just one thing more. What about Vetter?”

“Not yet, Mr. Carboy. Not yet.”

“You get some of my boys to stick with you. I don’t like my plans interfered with. Where are you?”

“In a place called Patty’s. A gin mill.”

“I know it. Stay there ten minutes. I’ll shoot a couple guys down. You got that handkerchief yet?”

“Still in my pocket.”

“Good. Keep your eyes open.”

He slapped the phone back and left me there. I checked the clock on the wall, went to the bar and had an orange, then when the ten minutes were up, drifted outside. I was half a block away when a car door slapped shut and I heard the steady tread of footsteps across the street.

Now it was set. Now the big blow. The show ought to be good when it happened and I wanted to see it happen. There was a cab stand at the end of the block and I hopped in the one on the end. He nodded when I gave him the address, looked at the bill in my hand and took off. In back of us the lights of another car prowled through the night, but always looking our way.

You smelt the place before you reached it. On one side the darkened store fronts were like sleeping drunks, little ones and big ones in a jumbled mass, but all smelling the same. There was the fish smell and on top that of wood the salt spray had started to rot. The bay stretched out endlessly on the other side, a few boats here and there marked with running lights, the rest just vague silhouettes against the sky. In the distance the moon turned the train trestle into a giant spidery hand. The white sign, SLIPSIDE, pointed on the dock area and I told the driver to turn up the street and keep right on going. I picked the bill from my fingers, slowed around the turn, then picked it up when I hopped out. In a few seconds the other car came by, made the turn and lost itself further up the street. When it was gone I stepped out of the shadows and crossed over. Maybe thirty seconds later the car came tearing back up the street again and I ducked back into a doorway. Phil Carboy was going to be pretty sore at those boys of his.

I stood still when I reached the corner again and listened. It was too quiet. You could hear the things that scurried around on the dock. The things were even bold enough to cross the street and one was dragging something in its mouth. Another, a curious elongated creature whose fur shone silvery in the street light pounced on it and the two fought and squealed until the raider had what it went after.

It happens even with rats, I thought. Who learns from who? Do the rats watch the men or the men watch the rats?

Another one of them ran into the gutter. It was going to cross, then stood on its hind legs in an attitude of attention, its face pointing toward the dock. I never saw it move, but it disappeared, then I heard what it had heard, carefully muffled sounds, then a curse not so muffled.

It came too quick to say it had a starting point. First the quick stab of orange and the sharp thunder of the gun, then the others following and the screams of the slugs whining off across the water. They didn’t try to be quiet now. There was a startled shout, a hoarse scream and the yell of somebody who was hit.

Somebody put out the street light and the darkness was a blanket that slid in. I could hear them running across the street, then the moon reached down before sliding behind a cloud again and I saw them, a dozen or so closing in on the dock from both sides.

Out on the water an engine barked into life, was gunned and a boat wheeled away down the channel. The car that had been cruising around suddenly dimmed its lights, turned off the street and stopped. I was right there with no place to duck into and feet started running my way. I couldn’t go back and there was trouble ahead. The only other thing was to make a break for it across the street and hope nobody spotted me.

I’d pushed it too far. I was being a dope again. One of them yelled and started behind me at a long angle. I didn’t stop at the rail. I went over the side into the water, kicked away from the concrete abutment and hoped I’d come up under the pier. I almost made it. I was a foot away from the piling but it wasn’t enough. When I looked back the guy was there at the rail with a gun bucking in his hand and the bullets were walking up the water toward me. He must have still had a half load left and only a foot to go when another shot blasted out over my head and the guy grabbed at his face with a scream and fell back to the street. The guy up above said, “Get the son...” and the last word had a whistle to it as something caught him in the belly. He was all doubled up when he hit the water and his tombstone was a tiny trail of bubbles that broke the surface a few seconds before stopping altogether.

I pulled myself further under the dock. From where I was I could hear the voices and now they had quieted down. Out on the street somebody yelled to stand back and before the words were out cut loose with a sharp blast of an automatic rifle. It gave the bunch on the street time to close in and those on the dock scurried back further.

Right over my head the planks were warped away and when a voice said, “I found it,” I could pick Johnny’s voice out of the racket.

“Where?”

“Back ten feet on the pole. Better hop to it before they get wise and cut the wires.”

Johnny moved fast and I tried to move with him. By the time I reached the next piling I could hear him dialing the phone. He talked fast, but kept his voice down. “Renzo? Yeah, they bottled us. Somebody pulled the cork out of the deal. Yeah. The hell with that, you call the cops. Let them break it up. Sure, sure. Move it. We can make it to one of the boats. They got Tommy and Balco. Two of the others were hit but not bad. Yeah, it’s Carboy all right. He ain’t here himself, but they’re his guys. Yeah, I got the stuff. Shake it.”

His feet pounded on the planking overhead and I could hear his voice without making out what he said. The next minute the blasting picked up and I knew they were trying for a stand off. Whatever they had for cover up there must have been pretty good because the guys on the street were swearing at it and yelling for somebody to spread out and get them from the sides. The only trouble was that there was no protection on the street and if the moon came out again they’d be nice easy targets.

It was the moan of the siren that stopped it. First one, then another joined in and I heard them running for the cars. A man screamed and yelled for them to take it easy. Something rattled over my head and when I looked up, a frame of black marred the flooring. Something was rolled to the edge, then crammed over. Another followed it. Men. Dead. They bobbed for a minute, then sank slowly. Somebody said, “Damn, I hate to do that. He was okay.”

“Shut up and get out there.” It was Johnny.

The voice said, “Yeah, come on, you,” then they went over the side. I stayed back of the piling and watched them swim for the boats. The sirens were coming closer now. One had a lead as if it knew the way and the others didn’t. Johnny didn’t come down. I grinned to myself, reached for a cross-brace and swung up on it. From there it was easy to make the trapdoor.

And there was Johnny by the end of the pier squatting down behind a packing case that seemed to be built around some machinery, squatting with that tenseness of a guy about to run. He had a box in his arms about two feet square and when I said, “Hello, chum,” he stood up so fast he dropped it, but he would have had to do that anyway the way he was reaching for his rod.

He almost had it when I belted him across the nose. I got him with another sharp hook and heard the breath hiss out of him. It spun him around until the packing case caught him and when I was coming in he let me have it with his foot. I skidded sidewise, took the toe of his shoe on my hip then had his arm in a lock that brought a scream tearing out of his throat. He was going for the rod again when the arm broke and in a crazy surge of pain he jerked loose, tripped me, and got the gun out with his good hand. I rolled into his feet as it coughed over my head, grabbed his wrist and turned it into his neck and he pulled the trigger for the last time in trying to get his hand loose. There was just one last, brief, horrified expression in his eyes as he looked at me, then they filmed over to start rotting away.

The siren that was screaming turned the corner with its wail dying out. Brakes squealed against the pavement and the car stopped, the red light on its hood snapping shut. The door opened opposite the driver, stayed open as if the one inside was listening. Then a guy crawled out, a little guy with a big gun in his hand. He said, “Johnny?”

Then he ran. Silently, like an Indian, I almost had Johnny’s gun back in my hand when he reached me.

“You,” Sergeant Gonzales said. He saw the package there, twisted his mouth into a smile and let me see the hole, in the end of his gun. I still made one last try for Johnny’s gun when the blast went off. I half expected the sickening smash of a bullet, but none came. When I looked up, Gonzales was still there. Something on the packing crate had hooked into his coat and held him up.

I couldn’t see into the shadows where the voice came from. But it was a familiar voice. It said, “You ought to be careful son.”

The gun the voice held slithered back into leather.

“Thirty seconds. No more. You might even do the job right and beat it in his car. He was in on it. The cop... he was working with Cooley. Then Cooley ran out on him too so he played along with Renzo. Better move, kid.”

The other sirens were almost there. I said, “Watch yourself. And thanks.”

“Sure, kid. I hate crooked cops worse than crooks.”

I ran for the car, hopped in and pulled the door shut. Behind me something splashed and a two foot square package floated on the water a moment, then turned over and sunk out of sight. I left the lights off, turned down the first street I reached and headed across town. At the main drag I pulled up, wiped the wheel and gearshift tree of prints and got out.

There was dawn showing in the sky. It would be another hour yet before it was morning. I walked until I reached the junkyard in back of Gordon’s office, found the wreck of a car that still had cushions in it, climbed in and went to sleep.

Morning, afternoon, then evening. I slept through the first two. The last one was harder. I sat there thinking things, keeping out of sight. My clothes were dry now, but the cigarettes still had a lousy taste. There was a twinge in my stomach and my mouth was dry. I gave it another hour before I moved, then went back over the fence and down the street to a dirty little diner that everybody avoided except the boys who rode the rods into town. I knocked off a plate of bacon and eggs, paid for it with some of the change I had left, picked up a pack of butts and started out. That was when I saw the paper on the table.

It made quite a story. GANG WAR FLARES ON WATERFRONT, and under it a subhead that said, Cop, Hoodlum, Slain in Gun Duel. It was a masterpiece of writing that said nothing, intimated much and brought out the fact that though the place was bullet-sprayed and though evidence of other wounded was found, there were no bodies to account for what had happened. One sentence mentioned the fact that Johnny was connected with Mark Renzo. The press hinted at police inefficiency. There was the usual statement from Captain Gerot.

The thing stunk. Even the press was afraid to talk out. How long would it take to find out Gonzales didn’t die by a shot from Johnny’s gun? Not very long. And Johnny... a cute little twist like that would usually get a big splash. There wasn’t even any curiosity shown about Johnny. I let out a short laugh and threw the paper back again.

They were like rats, all right. They just went the rats one better. They dragged their bodies away with them so there wouldn’t be any ties. Nice. Now find the doctor who patched them up. Find what they were after on the docks. May be they figured to heist ten tons or so of machinery. Yeah, try and find it.

No, they wouldn’t say anything. Maybe they’d have to hit it a little harder when the big one broke. When the boys came in who paid a few million out for a package that was never delivered. Maybe when the big trouble came and the blood ran again somebody would crawl back out of his hole long enough to put it into print. Or it could be that Bucky Edwards Was right. Life was too precious a thing to sell cheaply.

I thought about it, remembering everything he had told me. When I had it all back in my head again I turned toward the place where I knew Bucky would be and walked faster. Halfway there it started to drizzle. I turned up the collar of my coat.

It was a soft rain, one of those things that comes down at the end of summer, making its own music like a dull concert you think will have no end. It drove people indoors until even the cabs didn’t bother to cruise. The cars that went by had their windows steamed into opaque squares, the drivers peering through the hand-wiped panes.

I jumped a streetcar when one came along, took it downtown and got off again. And I was back with the people I knew and the places made for them. Bucky was on his usual stool and I wondered if it was a little too late. He had that all gone look in his face and his fingers were caressing a tall amber-colored glass.

When I sat down next to him his eyes moved, giving me a glassy stare. It was like the cars on the street, they were cloudy with mist, then a hand seemed to reach out and rub them clear. They weren’t glass any more. I could see the white in his fingers as they tightened around the glass and he said, “You did it fancy, kiddo. Get out of here.”

“Scared, Bucky?”

His eyes went past me to the door, then came back again. “Yes. You said it right. I’m scared. Get out. I don’t want to be around when they find you.”

“For a guy who’s crocked most of the time you seem to know a lot about what happens.”

“I think a lot. I figure it out. There’s only one answer.”

“If you know it why don’t you write it?”

“Living’s not much fun any more, but what there is of it, I like. Beat it, kid.”

This time I grinned at him, a big fat grin and told the bartender to get me an orange. Large. He shoved it down, picked up my dime and went back to his paper.

I said, “Let’s hear about it, Bucky.” I could feel my mouth changing the grin into something else. “I don’t like to be a target either. I want to know the score.”

Bucky’s tongue made a pass over dry lips. He seemed to look back inside himself to something he had been a long time ago, dredging the memory up. He found himself in the mirror behind the back bar, twisted his mouth at it and looked back at me again.

“This used to be a good town.”

“Not that,” I said.

He didn’t hear me. “Now anybody who knows anything is scared to death. To death, I said. Let them talk and that’s what they get. Death. From one side or another. It was bad enough when Renzo took over, worse when Carboy came in. It’s not over yet.” His shoulders made an involuntary shudder and he pulled the drink halfway down the glass. “Friend Gulley had an accident this afternoon. He was leaving town and was run off the road. He’s dead.”

I whistled softly. “Who?”

For the first time a trace of humor put lines at the corner of his lips. “It wasn’t Renzo. It wasn’t Phil Carboy. They were all accounted for. The tire marks are very interesting. It looked like the guy wanted to stop friend Gulley for a chat but Gulley hit the ditch. You could call it a real accident without lying.” He finished the rest of the drink, put it down and said, “The boys are scared stiff.” He looked at me closely then. “Vetter,” he said.

“He’s getting close.”

Bucky didn’t hear me. “I’m getting to like the guy. He does what should have been done a long time ago. By himself he does it. They know who killed Gonzales. One of Phil’s boys saw it happen before he ran for it. There’s a guy with a broken neck who was found out on the highway and they know who did that and how.” He swirled the ice around in his glass. “He’s taking good care of you, kiddo.”

I didn’t say anything.

“There’s just one little catch to it, Joe. One little catch.”

“What?”

“That boy who saw Gonzales get it saw something else. He saw you and Johnny tangle over the package. He figures you got it. Everybody knows and now they want you. It can’t happen twice. Renzo wants it and Carboy wants it. You know who gets it?”

I shook my head.

“You get it. In the belly or in the head. Even the cops want you that bad. Captain Gerot even thinks that way. You better get out of here, Joe. Keep away from me. There’s something about you that spooks me. Something in the way your eyes look. Something about your face. I wish I could see into that mind of yours. I always thought I knew people, but I don’t know you at all. You spook me. You should see your own eyes. I’ve seen eyes like yours before but I can’t remember where. They’re familiar as hell, but I can’t place them. They don’t belong in a kid’s face at all. Go on, Joe, beat it. The boys are all over town. They got orders to do just one thing. Find you. When they do I don’t want you sitting next to me.”

“When do you write the big story, Bucky?”

“You tell me.”

My teeth were tight together with the smile moving around them. “It won’t be long.”

“No... maybe just a short obit. They’re tracking you fast. That hotel was no cover at all. Do it smarter the next time.”

The ice seemed to pour down all over me. It went down over my shoulders, ate through my skin until it was in the blood that pounded through my body. I grabbed his arm and damn near jerked him off the stool. “What about the hotel?”

All he did was shrug. Bucky was gone again.

I cursed silently, ran back into the rain again and down the block to the cab stand.

The clerk said he was sorry, he didn’t know anything about room 612. The night man had taken a week off. I grabbed the key from his hand and pounded up the stairs. All I could feel was that mad frenzy of hate swelling in me and I kept saying her name over and over to myself. I threw the door open, stood there breathing fast while I called myself a dozen different kinds of fool.

She wasn’t there. It was empty.

A note lay beside the telephone. All it said was, “Bring it where you brought the first one.”

I laid the note down again and stared out the window into the night. There was sweat on the backs of my hands. Bucky had called it. They thought I had the package and they were forcing a trade. Then Mark Renzo would kill us both. He thought.

I brought the laugh up from way down in my throat. It didn’t sound much like me at all. I looked at my hands and watched them open and close into fists. There were callouses across the palms, huge things that came from Gordon’s junk carts. A year and a half of it, I thought. Eighteen months of pushing loads of scrap iron for pennies then all of a sudden I was part of a multi-million dollar operation. The critical part of it. I was the enigma. Me, Joey the junk pusher. Not even Vetter now. Just me. Vetter would come when they had me out of the way.

For a while I stared at the street. That tiny piece of luck that chased me caught up again and I saw the car stop and the men jump out. One was Phil Carboy’s right hand man. In a way it was funny. Renzo was always a step ahead of the challenger, but Phil was coming up fast. He’d caught on too and was ready to pull the same deal. He didn’t know it had already been pulled.

But that was all right too.

I reached for the pen on the desk, lifted a sheet of cheap stationary out of the drawer and scrawled across it, “Joe... be back in a few hours. Stay here with the package until I return. I’ll have the car ready.” I signed it, Helen, put it by the phone and picked up the receiver.

The clerk said, “Yes?”

I said, “In a minute some men will come in looking for the blonde and me. You think the room is empty, but let them come up. You haven’t seen me at all yet. Understand?”

“Say...”

“Mister, if you want to walk out of here tonight you’ll do what you’re told. You’re liable to get killed otherwise. Understand that?”

I hung up and let him think about it. I’d seen his type before and I wasn’t worried a bit. I got out, locked the door and started up the stairs to the roof. It didn’t take me longer than five minutes to reach the street and when I turned the corner the light was back on in the room I had just left. I gave it another five minutes and the tall guy came out again, spoke to the driver of the car and the fellow reached in and shut off the engine. It had worked. The light in the window went out. The vigil had started and the boys could afford to be pretty patient. They thought.

The rain was a steady thing coming down just a little bit harder than it had. It was cool and fresh with the slightest nip in it. I walked, putting the pieces together in my head. I did it slowly, replacing the fury that had been there, deliberately wiping out the gnawing worry that tried to grow. I reached the deserted square of the park and picked out a bench under a tree and sat there letting the rain drip down around me. When I looked at my hands they were shaking.

I was thinking wrong. I should have been thinking about fat, ugly faces; rat faces with deep voices and whining faces. I should have been thinking about the splashes of orange a rod makes when it cuts a man down and blood on the street. Cops who want the big pay off. Thinking of a town where even the press was cut off and the big boys came from the city to pick up the stuff that started more people on the long slide down to the grave.

Those were the things I should have thought of.

All I could think of was Helen. Lovely Helen who had been all things to many men and hated it. Beautiful Helen who didn’t want me to be hurt, who was afraid the dirt would rub off. Helen who found love for the first time... and me. The beauty in her face when I told her. Beauty that waited to be kicked and wasn’t because I loved her too much and didn’t give a damn what she had been. She was different now. Maybe I was too. She didn’t know it, but she was the good one, not me. She was the child that needed taking care of, not me. Now she was hours away from being dead and so was I. The thing they wanted, the thing that could buy her life I saw floating in the water beside the dock. It was like having a yacht with no fuel aboard.

The police? No, not them. They’d want me. They’d think it was a phoney. That wasn’t the answer. Not Phil Carboy either. He was after the same thing Renzo was.

I started to laugh, it was so damn, pathetically funny. I had it all in my hand and couldn’t turn it around. What the devil does a guy have to do? How many times does he have to kill himself? The answer. It was right there but wouldn’t come through. It wasn’t the same answer I had started with, but a better one.

So I said it all out to myself. Out loud, with words. I started with the night I brought the note to Renzo, the one that promised him Vetter would cut his guts out. I even described their faces to myself when Vetter’s name was mentioned. One name, that’s all it took, and you could see the fear creep in because Vetter was deadly and unknown. He was the shadow that stood there, the one they couldn’t trust, the one they all knew in the society that stayed outside the law. He was a high-priced killer who never missed and always got more than he was paid to take. So deadly they’d give anything to keep him out of town, even to doing the job he was there for. So deadly they could throw me or anybody else to the wolves just to finger him. So damn deadly they put an army on him, yet so deadly he could move behind their lines without any trouble at all.

Vetter.

I cursed the name. I said Helen’s. Vetter wasn’t important any more. Not to me.

The rain lashed at my face as I looked up into it. The things I knew fell into place and I knew what the answer was. I remembered something I didn’t know was there, a sign on the docks by the fishing fleet that said “SEASON LOCKERS.”

Jack Cooley had been smart by playing it simple. He even left me the ransom.

I got up, walked to the corner and waited until a cab came by. I flagged him down, got in and gave the address of the white house where Cooley had lived.

The same guy answered the door. He took the bill from my hand and nodded me in. I said, “Did he leave any old clothes behind at all?”

“Some fishing stuff downstairs. It’s behind the coal bin. You want that?”

“I want that,” I said.

He got up and I followed him. He switched on the cellar light, took me downstairs and across the littered pile of refuse a cellar can collect. When he pointed to the old set of dungarees on the nail in the wall, I went over and felt through the pockets. The key was in the jacket. I said thanks and went back upstairs. The taxi was still waiting. He flipped his butt away when I got in, threw the heap into gear and headed toward the smell of the water.

I had to climb the fence to get on the pier. There wasn’t much to it. The lockers were tall steel affairs, each with somebody’s name scrawled across it in chalk. The number that matched the key didn’t say Cooley, but it didn’t matter any more either. I opened it up and saw the cardboard box that had been jammed in there so hard it had snapped one of the rods in the corner. Just to be sure I pulled one end open, tore through the other box inside and tasted the white powder it held.

Heroin.

They never expected Cooley to do it so simply. He had found a way to grab their load and stashed it without any trouble at all. Friend Jack was good at that sort of thing. Real clever. Walked away with a couple million bucks’ worth of stuff and never lived to convert it. He wasn’t quite smart enough. Not quite as smart as Carboy, Gerot, Renzo... or even a kid who pushed a junk cart. Smart enough to grab the load, but not smart enough to keep on living.

I closed the locker and went back over the fence with the box in my arms. The cabbie found me a phone in a gin mill and waited while I made my calls. The first one got me Gerot’s home number. The second got me Captain Gerot himself, a very annoyed Gerot who had been pulled out of bed.

I said, “Captain, this is Joe Boyle and if you trace this call you’re going to scramble the whole deal.”

So the captain played it smart. “Go ahead,” was all he told me.

“You can have them all. Every one on a platter. You know what I’m talking about?”

“I know.”

“You want it that way?”

“I want you, Joe. Just you.”

“I’ll give you that chance. First you have to take the rest. There won’t be any doubt this time. They won’t be big enough to crawl out of it. There isn’t enough money to buy them out either. You’ll have every one of them cold.”

“I’ll still want you.”

I laughed at him. “I said you’ll get your chance. All you have to do is play it my way. You don’t mind that, do you?”

“Not if I get you, Joe.”

I laughed again. “You’ll need a dozen men. Ones you can trust. Ones who can shoot straight and aren’t afraid of what might come later.”

“I can get them.”

“Have them stand by. It won’t be long. I’ll call again.”

I hung up, stared at the phone a second, then went back outside. The cabbie was working his way through another cigarette. I said, “I need a fast car. Where do I get one?”

“How fast for how much?”

“The limit.”

“I got a friend with a souped-up Ford. Nothing can touch it. It’ll cost you.”

I showed him the thing in my hand. His eves narrowed at the edges. “Maybe it won’t cost you at that,” he said. He looked at me the same way Helen had, then waved me in.

We made a stop at an out of the way rooming house. I kicked my clothes off and climbed into some fresh stuff, then tossed everything else into a bag and woke up the landlady of the place. I told her to mail it to the post office address on the label and gave her a few bucks for her trouble. She promised me she would, took the bag into her room and I went outside. I felt better in the suit. I patted it down to make sure everything was set. The cabbie shot me a half smile when he saw me and held the door open.

I got the Ford and it didn’t cost me a thing unless I piled it up. The guy grinned when he handed me the keys and made a familiar gesture with his hand. I grinned back. I gave the cabbie his fare with a little extra and got in the Ford with my box. It was almost over.

A mile outside Mark Renzo’s roadhouse I stopped at a gas station and while the attendant filled me up all around, I used his phone. I got Renzo on the first try and said, “This is Joe, fat boy.”

His breath in the phone came louder than the words. “Where are you?”

“Never mind. I’ll be there. Let me talk to Helen.”

I heard him call and then there was Helen. Her voice was tired and all the hope was gone from it. She said, “Joe...”

It was enough. I’d know her voice any time. I said, “Honey... don’t worry about it. You’ll be okay.”

She started to say something else, but Renzo must have grabbed the phone from her. “You got the stuff, kid?”

“I got it.”

“Let’s go, sonny. You know what happens if you don’t.”

“I know,” I said. “You better do something first. I want to see the place of yours empty in a hurry. I don’t feel like being stopped going in. Tell them to drive out and keep on going. I’ll deliver the stuff to you, that’s all.”

“Sure, kid, sure. You’ll see the boys leave.”

“I’ll be watching,” I said.

Joke.

I made the other call then. It went back to my hotel room and I did it smart. I heard the phone ring when the clerk hit the room number, heard the phone get picked up and said as though I were in one big hurry, “Look, Helen, I’m hopping the stuff out to Renzo’s. He’s waiting for it. As soon as he pays off we’ll blow. See you later.”

When I slapped the phone back I laughed again then got Gerot again. This time he was waiting. I said, “Captain... they’ll all be at Renzo’s place. There’ll be plenty of fun for everybody. You’ll even find a fortune in heroin.”

“You’re the one I want, Joe.”

“Not even Vetter?”

“No, he comes next. First you.” This time he hung up on me. So I laughed again as the joke got funnier and made my last call.

The next voice was the one I had come to know so well. I said, “Joe Boyle. I’m heading for Renzo’s. Cooley had cached the stuff in a locker and I need it for a trade. I have a light blue Ford and need a quick way out. The trouble is going to start.”

“There’s a side entrance,” the voice said. “They don’t use it any more. If you’re careful you can come in that way and if you stay careful you can make it to the big town without getting spotted.”

“I heard about Gulley,” I said.

“Saddening. He was a wealthy man.”

“You’ll be here?”

“Give me five minutes,” the voice told me. “I’ll be at the side entrance. I’ll make sure nobody stops you.”

“There’ll be police. They won’t be asking questions.”

“Let me take care of that.”

“Everybody wants Vetter,” I said.

“Naturally. Do you think they’ll find him?”

I grinned. “I doubt it.”

The other voice chuckled as it hung up.

I saw them come out from where I stood in the bushes. They got into cars, eight of them and drove down the drive slowly. They turned back toward town and I waited until their lights were a mile away before I went up the steps of the club.

At that hour it was an eerie place, a dimly lit ghost house showing the signs of people that had been there earlier. I stood inside the door, stopped and listened. Up the stairs I heard a cough. It was like that first night, only this time I didn’t have somebody dragging me. I could remember the stairs and the long, narrow corridor at the top, and the oak panelled door at the end of it. Even the thin line of light that came from under the door. I snuggled the box under my arm and walked in.

Renzo was smiling from his chair behind the desk. It was a funny kind of a smile like I was a sucker. Helen was huddled on the floor in a corner holding a hand to the side of her cheek. Her dress had been shredded down to the waist, and tendrils of tattered cloth clung to the high swell of her breasts, followed the smooth flow of her body. Her other hand tried desperately to hide her nakedness from Renzo’s leer. She was trembling, and the terror in her eyes was an ungodly thing.

And Renzo grinned. Big, fat Renzo. Renzo the louse whose eyes were now on the package under my arm, with the grin turning to a slow sneer. Renzo the killer who found a lot of ways to get away with murder and was looking at me as if he were seeing me for the first time.

He said, “You got your going away clothes on, kid.”

“Yeah.”

“You won’t be needing them.” He made the sneer bigger, but I wasn’t watching him. I was watching Helen, seeing the incredible thing that crossed her face.

“I’m different, Helen?”

She couldn’t speak. All she could do was nod.

“I told you I wasn’t such a kid. I just look that way. Twenty... twenty-one you thought?” I laughed and it had a funny sound. Renzo stopped sneering. “I got ten years on that, honey. Don’t worry about being in love with a kid.”

Renzo started to get up then. Slowly, a ponderous monster with hands spread apart to kill something. “You two did it. You damn near ruined me. You know what happens now?” He licked his lips and the muscles rolled under his shirt.

My face was changing shape and I nodded. Renzo never noticed. Helen saw it. I said, “A lot happens now, fat boy.” I dropped the package on the floor and kicked it to one side. Renzo moved out from behind the desk. He wasn’t thinking any more. He was just seeing me and thinking of his empire that had almost toppled. The package could set it up again. I said, “Listen, you can hear it happen.”

Then he stopped to think. He turned his head and you could hear the whine of engines and the shots coming clear across the night through the rain. There was a frenzy about the way it was happening, the frenzy and madness that goes into a banzai charge and above it the moan of sirens that seemed to go ignored.

It was happening to Renzo too, the kill hate in his eyes, the saliva that made wet paths from the corners of his tight mouth. His whole body heaved and when his head turned back to me again, the eyes were bright with the lust of murder.

I said, “Come here, Helen,” and she came to me. I took the envelope out of my pocket and gave it to her, and then I took off my jacket, slipping it over her shoulders. She pulled it closed over her breasts, the terror in her eyes fading. “Go out the side... the old road. The car is waiting there. You’ll see a tall guy beside it, a big guy all around and if you happen to see his face, forget it. Tell him this. Tell him I said to give the report to the Chief. Tell him to wait until I contact him for the next assignment then start the car and wait for me. I’ll be in a hurry. You got that?”

“Yes, Joe.” The disbelief was still in her eyes.

Renzo moved slowly, the purpose plain in his face. His hands were out and he circled between me and the door. There was something fiendish about his face.

The sirens and the shooting were getting closer.

He said, “Vetter won’t get you out of this, kid. I’m going to kill you and it’ll be the best thing I ever did. Then the dame. The blonde. Weber told me he saw a blonde at Gulley’s and I knew who did this to me. The both of you are going to die, kid. There ain’t no Vetter here now.”

I let him have a long look at me. I grinned. I said, “Remember what that note said? It said Vetter was going to spill your guts all over the floor. You remember that, Renzo?”

“Yeah,” He said. “Now tell me you got a gun, kid. Tell me that and I’ll tell you you’re a liar. I can smell a rod a mile away. You had it, kid. There ain’t no Vetter here now.”

Maybe it was the way I let myself go. I could feel the loosening in my shoulders and my face was a picture only Renzo could see. “You killed too many men, Renzo, one too many. The ones you peddle the dope to die slowly, the ones who take it away die quick. It’s still a lot of men. You killed them, Renzo, a whole lot of them. You know what happens to killers in this country? It’s a funny law, but it works. Sometimes to get what it wants, it works in peculiar fashion. But it works.

“Remember the note. Remember hard what it said.” I grinned and what was in it stopped him five feet away. What was in it made him frown, then his eyes opened wide, almost too wide and he had the expression Helen had the first time.

I said to her, “Don’t wait, Helen,” and heard the door open and close. Renzo was backing away, his feet shuffling on the carpet.

Two minutes at the most.

“I’m Vetter,” I said. “Didn’t you know? Couldn’t you tell? Me... Vetter. The one everybody wonders about, even the cops. Vetter the puzzle. Vetter the one who’s there but isn’t there.” The air was cold against my teeth. “Remember the note, Renzo. No, you can’t smell a gun because I haven’t got one. But look at my hand. You’re big and strong... you’re a killer, but look at my hand and find out who the specialist really is and you’ll know that there was no lie in that note you read the first night.”

Renzo tried to scream, stumbled and fell. I laughed again and moved in on him. He was reaching for something in the desk drawer knowing all the time that he wasn’t going to make it and the knife in my hand made a nasty little snick and he screamed again so high it almost blended with the sirens.

Maybe one minute left, but it would be enough and the puzzle would always be there and the name when mentioned would start another ball rolling and the country a little cleaner and the report when the Chief read it would mean one more done with... done differently, but done.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ