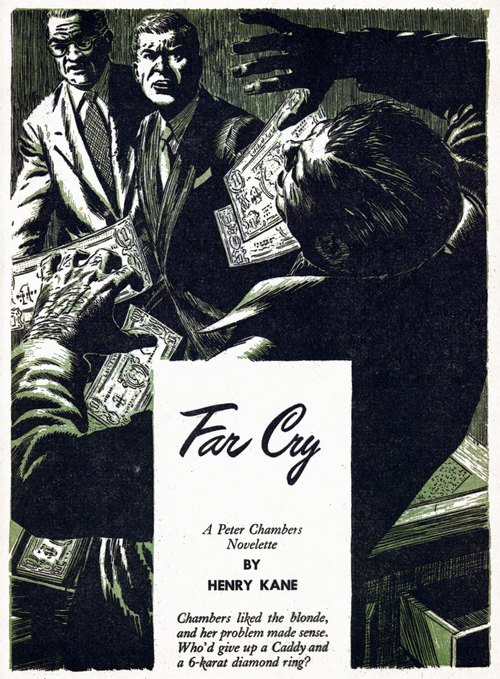

Far Cry by Henry Kane

1.

It’s a far cry from a beach chair to an operating table, but I made it — in one day. It’s a far cry from sunshine, the peaceful blue of a swimming pool, a lovely girl poised on a diving board — to two bullets in my body, the white glare of surgery, and the antiseptic walls of a hospital room. But I made it. Same day. It’s a far cry from lush pulchritude to plush hoodlumism... or is it?

It isn’t.

The party the night before had been the best kind of party that happens in New York. It had been the after-opening-night affair of a brand new musical given by the producer (and assorted angels) in a high-ceilinged sixteen room duplex on Central Park West. The musical was a smash, and it was a nice, happy party.

Happy, that is, for everybody but me.

Because me: it was a girl again.

She was brown, deeply tanned. She was blonde, with glistening lips. She was tall, shapely tall. Her eyes were blue and shining, her mouth red and shining, her hair gold and shining. Her gown was black nakedness, glistening satin, simple without whirls, and firm to her figure. It started at the rise of her breasts and descended, tightly, to the calf. She wore black high-heeled pumps and black nylons. If you can get away with black nylons, you’re something. She was something. When she walked, she swayed, her head up and her shoulders back as though she were pushing against a high wind. If you watched her going away, you saw the thrust-back shimmering shoulders, a pinched-in waist, and then a number of curves. I watched her, coming and going. She wore no spot of jewelry except one, a brilliant engagement ring, at least three carats.

The engagement ring, of course, spoiled the party for me.

I caught my first glimpse of her late, it must have been two o’clock in the morning. Maybe she’d arrived late or maybe she’d been swallowed up by the four hundred people present, the sixteen rooms, the upstairs and the downstairs. There was a crap game going, a raucous man-and-lady crap game, and I had the dice, it was my turn to shoot. I was getting down to one knee and my glance flicked up — when I saw her, at the far end of the room. My lust for gambling instantly died. I passed the dice, straightened up, and went to her — but now she was going away. I lost her at the stairs. I was captured by twin fat ladies in horn-rimmed glasses and identical green dresses who wanted to talk about the rumbles of revolution in Africa. I got out of that by the judicious injection of a few inoffensive items of profanity, and I left them, slightly aghast and clucking.

Downstairs, after a rambling search, I found her, surrounded by men in tuxedoes, none of whom I knew. But then the producer came by, not sober, but in a reasonable state of comprehension. I talked fast, nudged a little, winked a lot and held on to his elbow until a light came into his fast-going-opaque eyes, and he said, “Okay, okay, I get it.”

He broke through the phalanx of black ties, and brought forth the lady. He maneuvered us to relatively isolated propinquity, glared at her, glared at me, and then, brilliantly, he said, “You two ought to meet, you two certainly ought to meet. Lola Southern, Peter Chambers.”

“How do you do?” I said.

“Why?” she said.

I said: “Pardon?”

She said: “Why?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Why,” she said, “must we two meet?”

“Oh. I don’t know, really don’t know, but he’s been saying that to me all night, pointing you out to me, and saying it, over and over.”

“Has he?”

“He has.”

“All night?”

“All the livelong night.”

“I only got here ten minutes ago.”

What do you answer to that? You don’t answer.

But she was kind. Her blue eyes moved over me, slowly, and then she smiled, and brother, that tore it. When she smiled it was two rows of perfectly white teeth ringed by the glistening red of her lips, but that wasn’t it. The lips came out from the teeth in a shining pout, and the eyes narrowed, and there was the faintest flutter of the nostrils of her small nose. Even that wasn’t it. It was the expression that the smile put on her face. It was as though she had just heard the most wildly salacious story, and had loved every syllable of it, and had smiled despite herself, smiled holding back, smiled trying to restrain a manifestation of reaction. It put prickles on your scalp.

She said, “Are you in the show?”

“No. I’m not in the show.”

“You certainly look theatrical enough. You’re handsome. I never make bones about that. I tell them right to their faces. Better that way. Man shaves and fixes and primps and things, and then he runs up against a doll and wonders how he’s coming over. Doll says nothing, enigmatic. Poor guy keeps wondering. Thinks he’s lost his sex appeal. Well... you haven’t. I love a good-looker. What’d you say your name was?”

“Chambers. Peter Chambers.”

“Not with the show, huh?”

“No. Nor are you.”

Now she frowned. Beautifully. “How would you know that?”

“Two plus two. If you were in the show — you’d know I wasn’t.”

“Pretty good.”

“That’s my business.”

“What?”

“Two plus two.”

“I don’t get it.”

“I’m a cop.”

“Cop? No. You’re not a policeman. You couldn’t be...”

“Sort of. Private. I’m a private detective.”

“Not really.”

“Yep.”

“You know, it’s hard for me to take that, I mean, well, private detectives, I just didn’t think they existed, I thought they were something, well, that the movies created for their own sinister purposes. What did you say your name was?”

“Peter Chambers.”

“You know,” she said, the smile going away, a reflective light coming into her eyes, “I’ve heard of you.”

“Thanks.”

“Vaguely, but I’m sure I have. How about a vodka martini, Mr. Peter Chambers?”

“Will you stay put if I get a couple?” I asked.

“I’ll try.”

I went away, and I came back perilously balancing two brimful martinis. Miss Lola Southern was surrounded by five speculative males, three in tails and two in black ties, and somebody had moved fast — Miss Southern had a vodka martini in each fist. Just between you and me, Miss Southern was tighter than a jammed-down hat in a sleet storm. Had been, from the first moment we’d spoken. She laughed loud and tinklingly, and raised the left martini high. That’s when I saw the engagement ring.

I mumbled a sneaky toast, clinked glasses, and drank both martinis, gulpingly. I couldn’t crash the glasses into a fireplace, because there was no fireplace, so I slid them on the first tray that went by. Then I went back to the crap game and saw no more of Lola Southern that night. Worse, I dropped two hundred and sixty-nine dollars betting, waiting for somebody to make a roll.

Nobody did.

2.

Next morning I awoke to the urgings of small explosions inside of me. I crawled out of bed and transported a large head to the cold water faucet, precariously placed it beneath, and let it shrink to size. Then I showered, shaved, drank tomato juice from the can, and went to the office. A rainy day would have suited my mood, but when your luck runs bad, it runs, as you know, all bad. The day was fine, warm, clear and bright. Sun shone thick and yellow.

My reception at the office was better. It was twelve-thirty, but there were no messages, no mail, no calls, no checks, no clients, and my secretary, deathly pale, complained of a virus in the stomach. I told her to go home. She plugged in the switchboard for rings in my office, and went. For me, naturally, there was but one thing to do: grab a cab up to the Polo Grounds, strip down and bake out in left field. I proceeded to do exactly that. I switched off the lights, shut off the switchboard, and left it up to Answering Service to take care of my business. I opened the door and almost ran head-on into Lola Southern.

“Coming or going?” she said.

“That’s up to you.”

“I don’t know just how to take that.”

“That's up to you too.”

“I was going to invite you out.”

“Fine. I was going out.”

“Where?”

“You name it.”

“No coaxing required?”

“Not when it’s you.”

We went to the elevator, waited, went down, and I let her out before me. She wore a powder-blue suit and toeless blue high-heeled shoes with intricate straps. Her ankles were stylishly slender, curving up to full round-muscled calves. Her golden hair was caught in a ring in back, pony-tail, and it swung down to her shoulders. Her walk was the walk of last night, the provocative swaying-ever-so-slightly, but enough to cause the gentlemen in the lobby to purse their lips in unemitted whistles.

Outside, parked smack against a No Parking sign, was a Caddy convertible, this year’s model, powder-blue and sleek. “That’s it,” she said.

“This?”

“Yep.”

“Not bad.”

She got in, slid into the driver’s seat, and I got in after her. She said, “I took a chance on a ticket. I was anxious to see you.”

“You could have called.”

“I can’t abduct you over the telephone.”

We pulled away from the curb and headed north, turned right at Fifty-Ninth, and got on to the bridge. She said, “Aren’t you curious as to where we’re going?”

“I’m perfectly satisfied.”

“You're a strange one, aren’t you?”

“No.”

Silence, then, all the way to the smooth Triboro. Then she said, “I want to apologize for last night.”

“Apologize?”

“I was looped. But looped.”

“I know that. But you were awfully cute.”

“Thanks.”

I said, “May I ask a question?”

“Shoot.”

“What do you do?”

“Do?”

“For a living.”

“I’m a diver.”

“Come again?”

“A diver.”

I digested that for a moment. I said, “You mean you’re one of those people that puts a helmet on her head and looks at fish, and things?”

“No. I put a bathing suit on my body, and part water. Gracefully.”

I digested that for a while. Then I said, “This you do for a living?”

“I was a crackerjack amateur once. Now I’m a professional. It pays the rent.”

“Does it pay for Cadillac convertibles too?”

“It doesn’t. But that’s another story. One which I’m going to tell you.”

“Now?”

“Not now. Later.”

I digested that too. I love to listen to stories. Stories mean business and business was something I could use, badly. The lady hadn’t barged in on the private detective strictly for the purpose of taking him for rides over bridges. I’d been waiting for the first leak in the dike, and this seemed to be it. So I changed the subject. I got off crass commercialism. I said, “Diving. Sister, I’d love to watch you sometime.”

“You’re going to. Quite soon. That’s where we’re heading.”

“We’re going diving?”

“Not we. I. There’s a new water show going to open next month. I’m to be one of the stars. Little guy that runs it owns a terrific estate out at Lido. Swimming pool, and all. He’s in Europe now, but he told me I could use the place any time I wanted. For practice, that is.”

“Ever use it before?”

“As a matter of fact, I haven’t, that is, not since he’s gone. I have my own spots for practice. But I thought it would be a good idea today. It’s warm and lovely out, and I wanted to be alone with you, somewhere where we could talk. Any objections?”

“Not a one.”

3.

The place in Lido was like a Moorish castle. We drove up a winding pebbled roadway to a massive iron gateway. I got out and pushed a bell that sounded like a fire gong. A man came out of a small house perhaps a hundred yards in, and trotted down to us. Lola waved to him. I got back into the car while he opened the gates. We rolled through, Lola and the man exchanged further waves, and then we lost him as we went up another winding roadway until we arrived at the house proper. House? It was a mansion, if by mansion you can imagine a red stone edifice of beautiful architecture, a sprawling, six-storied, spic-and-span hunk of work, with at least a hundred rooms. The man at the gate must have phoned in. A house-man came running down the stairs. Lola pulled up the brake, and we both got out. The houseman said, “Welcome. It’s a pleasure to see you, Miss Southern.”

“Hello, Fred. You’ll take care of the car?”

“Of course. Would you and the gentleman like lunch?”

“No, thank you. I’m going to put in a few licks of practice. The pool’s in order, I take it.”

“Oh, yes.”

“And then the gentleman and I are going to want to talk, in private. There’s nobody at the bath-house, is there?”

“Nobody. There’s nobody here at all, except the servants, and there’s nobody expected. Would you like me to drive you out, Miss?”

“No, thank you, we’ll walk.”

It was a hike of three quarters of a mile, and I was no high diver in the pink of condition. I practically fell into the bath-house. Which was another joke. When you say bathhouse you think bath-house. This wasn’t what you’d think. This was a red-brick ranch-house, with a kitchen that could have provided for a small army, and about twenty beautifully furnished bedrooms, each equipped with its own plumbing. In the kitchen, I opened one of the refrigerators, stocked from top to bottom, grabbed a bottle of beer, opened it, and drank it neat.

I said, “You know the guy that owns this joint?”

“He’s married,” she said sadly.

“Let’s get to the pool,” I said.

“I’m ready. And eager.”

“What do I do for trunks? Or don’t I?”

“Every room has men’s trunks and ladies’ suits. Find a pair that fit you. They’re all sterilized. See you at the pool.”

I wandered around looking the place over, mumbling and remumbling about how it’s nice to have dough. Then I found a pair of yellow trunks that fit. I got out of my clothes, pulled into the trunks, and went out to the pool.

It was wide and long and transparently blue and unrippled and peaceful. There were beach chairs on all four sides, and iron chairs and tables, and coolers for the colas, with cabinets fixed in the sides. I opened one cabinet. It had everything from gin to champagne.

Lola was nowhere in sight. I couldn’t wait. I was steaming from every pore. I went into the pool and rippled up the water plenty. It was cold and refreshing. I swam around a bit and climbed out. I fixed a drink out of one of the cabinets, spread out in a beach chair, and let the sun dry me out. I felt good, real good.

I felt better a moment later. Lola appeared on the far side in a white bathing suit, a white cap, and a towel about her shoulders. Lola in clothes was something. Lola in a bathing suit was something more. I wondered about Lola without a bathing suit.

She smiled at me, and even from that distance, I felt it, the begging smile, the smile of the secret thoughts, the lush, warm, wet, shining smile. Then she flung off the towel, and climbed up to the top board, posed poised, and dove. It was beautiful. It took your breath away. It was clean, sharp, almost geometrically beautiful. For the next half hour, I was treated to quite an exhibition. It was so beautiful, I almost forgot her body. Almost.

Then she called, “That’s all. Finished. Come on in for a quick dip, and we’ll quit.”

I jumped in and we swam together. Then she came close, treading water, and the smile was small, and intense. I put my arms around her and kissed her there in the water. I kissed her for the first time. She clung, all the way. Then she moved back and looked at me, our feet treading water together.

“I like you,” she said. “I like you very much. Maybe I’m in love with you. It happens.”

“That’s why you ran off last night.”

“Maybe. Maybe that’s why I did. But I came back, didn't I?”

“That the only reason you came back? Because ‘Maybe I'm in love with you.’ ”

She laughed, the tinkling laugh, and her eyes were gentle. “That,” she said, “and another reason.” She splashed away. “Let’s get out of here.”

Top-side, she took off the cap and shook out her hair. She wiped her face with the towel, and wiped mine. “Let’s sit in the sun for a while,” she said, “and talk.”

“Sure.”

Her body glistened. Her thighs were full, and sun-brown, and long, and glistening. She was a glistening girl, that was the sum of her, her lips, her hair, the flesh of her. I wondered whether that brown was her color, if she was brown all over.

“Let’s sit,” she said. “I think you can help me.”

“Now we come to it,” I said.

We lay out side by side in the lounging chairs. The sun warmed down. I was drowsy, but I was listening.

“It’s tough on a girl,” she said. “This racket.”

“But you’re good. You’re wonderful.”

“It’s peanuts, if you have to depend on it for your living.”

“Do you?”

“I didn’t. But I do now.”

“I don’t get that.”

She stretched, moving her arms up over her head. I was less drowsy at once. “I was married once, as a kid. My husband was much older than I, almost thirty years older. He left me a good deal of money. So it seemed, at least.”

“You mean he died?”

“Yes.”

“Natural causes?”

“Yes.”

“Then the money petered, that what you mean?”

“Yes.”

“But this diving deal...?”

“It’s nothing.”

“But you can move up from that. You’ve got talent, and you’re beautiful, really beautiful.”

“Thanks. Move? In what direction?”

“Motion pictures. TV. You know. Others have made that jump. Swimmers...”

“No good, my friend. You’ve got to learn to be an actress.”

“Others have.”

“They started when they were kids. Let’s face it, pal. I’m twenty-six, now. You don’t start a motion picture career, from scratch, at twenty-six.”

“Maybe so,” I said.

“Oh, I’ve had offers, from all kinds of promoters. Nothing could happen, and I know that. Nothing except trouble from a lot of men. That’s a hard little head on these shoulders.” She touched her hair.

“And what’s on the finger?”

“Pardon?”

“The ring.”

“That’s part of the story.”

“Three carats, isn’t it? At least that.”

“It’s six.”

“Shows you. I’m no judge. So let’s get to the story, huh?”

She wriggled to get comfortable. More and more I was getting less and less drowsy. She said, “I’ve been around. Let’s get that out of the way. I’ve distributed my favors, if that’s what it’s called. But judiciously. With people I’ve liked. And I’ve accepted favors. From people I like. But I’m no bum. Let’s get that out of the way too.”

“Fine. You’re all right.”

She held out the hand with the sparkling ring. “Four months ago, I became engaged. You know Ben Palance?”

Old Ben Palance was a friend of mine, a rugged leather-faced man with a full head of strong white hair. He was a man of seventy, a retired sea captain.

“Improving on the first husband?” I said. “But this one’s got no loot.”

I was sorry I had said it before I had gotten it out. Ice jumped into her eyes.

I said, “I’m the bum around here. I’m sorry. This just isn’t my day.”

“Remember I had said I’d heard of you,” she went on. “It came to me later last night. I had heard of you through Ben. He thinks the world of you.”

“And I of him. But what’s the connection?”

“I’m engaged to Ben’s son, Frank Palance. Do you know him?”

“No. I’ve heard about him, but I never met him.” I squirmed around in the chair. “Look, don’t get sore, and take this as it’s meant. You’re a girl who’s used to good things, who sees no future in her profession, who figures to marry well... so that the good things can keep coming. Am I all wrong?”

“No.”

“So what’s with Frank Palance?”

“I don’t understand.”

“From what I’ve heard, he’s a nice guy, and all that, but he’s a sailor, or something, first mate on a boat, something like that.”

“That’s wrong.”

“His circumstances must have improved.”

She lifted her left hand. “This ring was bought by Frank. The convertible was a gift from Frank. He has a fully staffed house up in Scarsdale, and a penthouse apartment in town. He’s not a first mate on a boat, he’s the master of his own freighter.”

“And how his circumstances must have improved.”

“I met him about four months ago. Whirlwind romance, one of those things. But it was a mistake. More and more did I realize it. Frank is bad. He’s mean and vicious. I’m frightened to death of him. I can’t possibly tell you how bad these four months have been. Luckily, he’s been at sea part of that time.”

“Where do I come in?”

“I want you to help me.”

“How?”

“I want you to protect me from Frank. And” — she hesitated a moment — “I want to keep the things he gave me. I’ve earned them.”

“What’s the status right now?”

“Status?”

“The romance.”

“I broke the engagement the day he left on his last trip.”

“When was that?”

“Three weeks ago.”

“When’s he due back?”

“Tonight.”

I squirmed some more in the chair. I was getting to an uncomfortable subject. I said, “What about the fee?”

“Fee?”

“A man’s got to cat.”

“There’s nothing I can offer you. I’m practically broke.”

“Nothing?”

Our eyes met for a quick moment, and then, suddenly embarrassed, we both looked toward the sun, blinkingly.

I closed my eyes. I said, “Was there a bust-up, an argument, something?”

“There was.”

“An immediate cause for same?”

“Yep. A voluptuous brunette named Rose Jonas. Sings at the Raven Club. In a way, to me, she was a Godsend. It gave me an excuse.”

“How long has he known her?”

“Couple of months.”

“How’d he meet her?”

“I don’t know.”

“When’d the bust-up take place, and where?”

“I told you. The day he left on his trip. At his town apartment. We went at it hot and heavy. He hit me, once. He told me to return the ring, and the car, and he told me he was changing his policy, at once, in her favor.”

I opened my eyes. I sat up and faced her. Policy. That had the smell of money. Money. Bloodhounds don’t have a better smell when it comes to Uncle Sam’s crinkling green. “Policy?” I said.

“A kind of gesture, I suppose. Like the six carat ring, and the convertible.”

“Gesture, shmesture... what about the policy?”

“It was on his life, with me as beneficiary. Double indemnity for accidental death.”

“You sound like an insurance salesman. Never mind the quirks. How much?”

“Fifty thousand dollars.”

“Not bad.”

“But he said he was changing it. And if he said it, he did it. So get that lustful look out of your eyes.”

“That lustful look,” I said, “has nothing to do with no policies.”

“Hasn’t it?” She stood up. “Do you take my case?”

“I’ve got to think about it.”

“Well, think back at the bathhouse. I’m broiling here.”

We got up, and started back. She said, “I’m starving. Don’t get dressed. We’ll shower, and lounge, and I’ll fix you something special to eat.”

“Fine by me.”

I lost her among the many bedrooms of the bath-house. I took a long warm shower. Then I shaved again and doused my face with some sweet-smelling stuff I found in the medicine chest. I combed my hair. The closet had a snowy white terry-cloth robe. I put that on and it snuggled the warmth of the sun my body had acquired. I felt good. The drowsiness returned. But I had work, protection work, before I lay out on the wide soft bed.

I found pen, ink and paper in a table drawer. I wrote: “I hereby retain Peter Chambers to protect my interests in my relationship with one Frank Palance. His fee is to be twenty percent of whatever may accrue to me from the life insurance policy in the name of the said Frank Palance.” I dated it, and drew a line for her signature. I left it on top of the table. Then I sprawled out on the bed, sighed, and was ready for a nap, when the knock sounded at the door.

“Come in,” I called.

She wore a snowy white terry-cloth robe. It was different from mine, and she filled it differently. It puffed out on top, was tightly belted in the middle, and puffed out again below that. A pulse near my heart began doing an imitation of a trip-hammer. Her hair was combed out, blonde, loose and flowing, there was make-up on her face, and her red lips pouted, shining. Romantic-like, I said, “Sign the thing on the table.”

She looked at it, signed, laid the pen away, said, “For a smart guy, you’re cheating yourself. That policy is no longer in my favor. I know Frank. If it is, more power to you. I’d be happy to pay that twenty percent. You’d be much better off if Rose Jonas signed this contract.”

“The hell with Rose Jonas.”

“Thank you. Are you going to work for me?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’re entitled to a real fee. Aren’t you?”

“Am I?”

“Down payment,” she said and came near me. “Down payment,” she said, and the smile was off her face, and there was the faintest trembling of her nostrils, and she bent over me, and she smelled sweet, salt-sweet, and she put those full red wet lips on mine.

I didn’t move. I didn’t put my arms around her. Our only contact was mouth on mouth, wide-spread, clinging. Then her cheek moved along mine, and her voice was a quick-breathing whisper in my ear, and she said, “I love you, Mr. Chambers. I’m crazy, and I know it, but I love you, I love you...”

Then she stood up, full-length, straight and breathless by the side of the bed; no smile now, only the shine of tears in her eyes, and the shine on her mouth, the ever-present soft wet shine, a lovely shine.

“I thought of something a while ago,” I said.

“What?”

“You’re so brown.”

“I’m not. I’m a blonde. I'm milky white. The brown is the sun.”

“I love the brown too.”

“It’s ridiculous. It’s like a two-tone person. White and brown, white and brown.”

I didn’t say it, I said nothing, I didn’t say, “I want to see,” I didn't say a word, and that small sweet secret special smile crept back on her face, the red pouting smile, the white teeth half exposed; her eyes didn’t leave mine, and her fingers dug into the tight-clasped belt, and she flung away the terry-cloth robe.

4.

We got back to the city at four-thirty. She lived at 277 Park Avenue. I kissed her and I said, “Stay put, I’m going to work.” I took a cab up to Eighty-sixth and Broadway, The Monterey, where old man Palance lived. I used the house phone to call up. His invitation was quick and hearty. He was waiting at the open door, upstairs. He wore a T-shirt, slacks and sandals. He was big, but there was nothing flabby about him.

“Glad to see you, Pete. It's nice of you to come calling.”

“Glad to see you, Ben.”

“Come in, come in.” He closed the door behind me. “Let me fix you something.” He waved a hand at a quarter full bottle on a bureau. “Me, I’m drinking bourbon. But I got anything a guest wants, and if I haven't, I call down for it. What’ll it be?”

“Nothing, thanks, Ben.”

He wrinkled his eves at me, the leather of his cheeks making pouches around them. “What's the matter? Sick?”

“No.”

“Wagon?”

“No.”

“So it figures it ain't a social call. What’s the beef, Petie?”

“It’s about Frank.”

An edge came into his voice. “He in trouble?”

“Why?”

“Because he’s been begging for it.” He gulped bourbon, pulled up a chair for me, and one for him, said, “Sit down.” He filled an old pipe and lit up. “My lady gave me seven kids, peace be with her. Six are the best. One’s rotten.” He shrugged. “I don’t know. Maybe that’s a good average. What’s the beef, Pete?”

I roughed an outline for him, sketchily. When I was through, he shook his head, talked with the pipe between his teeth. “She’s a good kid, that Lola. Too good for him. Look, Pete. Come with me tonight. I’m meeting him when he gets off ship. Tonight, at his office. He’s due in at eight o’clock. He’s thirty-five years old, but I’m still his old man. I got a key to his office, and I’m waiting for him tonight. Tonight we make it or break it. It’s been constantly on my mind for the past three weeks.”

“What good’ll I do? I don’t belong.”

“You’re my friend. He knows you’re my friend. He knows all about you. You’ve never met him, have you?”

“No.”

“Come down with me tonight, Pete. It figures for a shindig. Let’s get it all over with in one bunch. You got a client to represent. No?”

“Yes.”

He smiled, grimly, around the pipe. “I hate it. Maybe that’s why I need company. Maybe I need somebody to lean on, somebody young, and tough. Nice way for a father to talk.”

“I’m sorry, Ben.”

“If he isn’t good, I don’t care whose son he is. But it’s time he knows that I know. You coming?”

“If you want me to, Ben.”

“I want you. Where'll I pick you up?”

“I’ll pick you up. Here. About seven-thirty.”

“Good boy.”

Next stop was the Raven Club on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village. This was a cellar trap with all the frills. The entertainment went from torch singers to cooch dancers to female impersonators who didn’t have to work too hard for the impersonation. It was a clip joint but it did a steady business with the uptown trade. It was an old time joint, switching its acts regularly. Some of our top-notchers played the Raven on their way up, and hit it once or twice coming down. It was dimly lit, with black walls, small black tables, small black chairs, and indirect red lighting, shooting upward. It was a late spot, going into full action at about ten and winding up with last call for alcohol at four in the morning. This time of early evening the room proper was closed, but the bar was open, catch-as-can, for any thirsty customers that might fall in.

The manager’s name was Tom Connors.

At the bar of the Raven, I ordered a scotch and water, and I said, “Tom around?”

“Who’s asking?”

“Pete Chambers.”

“Just a minute.”

The bar was a sort of tap room, separated from the main room, with booths against the walls, and one tired waiter. The bartender signalled to the waiter, who went away and came back with Tom. Tom rubbed a big paw across my back. “Hi, pal. Long time no.”

“Have a drink, Tom.”

“Don’t mind if I do. Gin and tonic, in an old-fashioned glass. And no check on any of it. This guy’s a pal of the house.” He got his drink, saluted me with it, said, “It’s a fact, pal. Really long time no.”

“Can we sit in a booth, Tom?”

“Why not? Bring your drink.” We moved away from the bar and slid into a booth opposite one another. He said, “What’s personal, pal?”

“You know a guy named Frank Palance?”

“Yep.”

“What kind of guy?”

“Don’t know what kind of guy. Customer, period. Pays on the nose and no squawk.”

“Who’s Rose Jonas?”

“Doll sings here.”

“Now what’s the connection between them?”

He drank gin from the wide glass, his teeth clicking against it, and he grinned over the rim. “I like it when you talk to me like that, pal. Real legal-type jabs.”

“What’s the connection?”

He pushed away the empty glass and folded his hands on the table. “Boy loves girl. That’s the connection.”

“Does girl love boy?”

“She don’t.”

“How’s it shape?”

“She’s playing him.”

“She got somebody? A real boyfriend?”

His eyebrows went up as he nodded. “Big.”

“Who?”

“Joe April.”

I shoved that through a sieve in my mind. Nothing came out. I said, “Joe April? Can’t be as big as you saw I’ve never heard of him.”

“West Coast hood. Frisco. Moved into town with a little mob. Plays it big and throws the loot around like toilet paper. He’ll either make it in this town, or he’ll get cooled fast. Got a lot of guts, but I’m not too sure about the brains. I’ve seen them all, pal. The smartest are the quiet ones. This guy’s got too much flash.”

“And Rose Jonas?”

“He brought her in from the Coast.”

“Then what’s with Frank Palance?”

“This April guy’s been knocking off every jane in town. Palance is a good-looking boy. I figure she’s using him for a stick against April. I also figure it don’t work. I figure April’s got a bellyful of Rose. And I got a hunch Rose knows it. She’s even been short of dough lately.”

“Let’s say April stopped laying it on the line. This Frank Palance, from what I hear, is no piker. Rose shouldn’t be starving.”

“You don’t know Rose, pal. Loves a buck, but she can spend it faster’n any dame you ever saw. She can flip for champagne for the house, two hundred customers, just because she likes the applause.”

“She any good?”

“Fair.”

“Good-looking?”

“Beauty.”

“You think she likes Frank?”

“I think she hates him.”

“But why?”

“When a dame deals from a cold deck, and it goes wrong, she tears up the cards. You know dames. The way she looks at him sometimes, when he don’t know she’s looking.” He shook his head. “Brother, it ain’t good.”

“How’d he meet her?”

“April introduced them.”

“How’s he know April?”

“Search me.”

5.

I picked up old Ben at seven-thirty. We had a couple of drinks, talked a while, and took a cab down to South Street. We got there at five minutes to eight. South Street, in the springtime, at five minutes to eight, is quiet, smoky, desolate, the old buildings dark and jagged. We got out of the cab and I paid. The street was empty except for a black car, parked and silent, a man at the wheel. Nothing else. I followed the old man into a narrow hallway that smelled of spice. We clumped up a flight of wooden stairs. A door at the head of the stairs gave back the legend by the yellow hall-light: Frank Palance, International Freight Forwarder. The old man mumbled, “Pretty fancy title.” He shoved a big key in the door, pushed the door in, left the key stuck in the lock. He flipped on a light, and we were in an old-fashioned, large, one-room office. There was a desk, chairs, benches, filing cabinets, a phone, and a large safe at the wall opposite the entrance door.

I said, “It’s a little eerie down here, isn’t it, this time of night?”

“Naw. Why eerie?” He pulled open the bottom drawer of the desk and produced a bottle and a couple of tumblers. “It’s scotch,” he said. “That’s your drink, ain’t it?”

“What about you?”

“I can drink anything.” He poured into the tumblers. “Want water with yours?”

“Please.”

He went to a corner sink, turned the faucet, let the water run.

He came back and handed me the glass. He drank his neat. He pulled up a chair, sat, and put his legs up on the desk. He kept refilling the glass, drinking the whiskey like water. I sat on a wooden bench and used my drink nibblingly. He began to tell me stories of the sea, and an hour went by like that. Then the door swung open silently, and a man said, “Hi, skipper.”

He had made no noise coming up. He was a lithe man, tall, and he needed a shave. He had black, quick-moving eyes, heavy black eyebrows, a square jaw, and a strong chin. He wore dark wide trousers, a black turtle-neck sweater, a pea-jacket and a seaman’s visored cap. One hand was weighed down with a big valise.

The old man got his feet off the desk and stood up. I set my glass down on the bench and stood up too. The young man put down the valise and shook hands with old Ben. He said, “Hi, skipper,” again, and then he said, “Who’s your friend?”

“Pete Chambers.”

“Well... I’ve heard of you.” He stuck his hand out and I shook it. He said, “I’m Frank. The black sheep.” He smiled. His teeth were white and large. He pushed his cap back on his head. His hair was black, thick and curly. He saw the bottle on the desk, poured into his father’s glass, drank to the bottom, and set the glass down with a bang. He said, “Okay. To what do I owe the pleasure of this visit?”

“We’re going to talk, son. Now.”

Frank pointed a thumb at me. “In front of him?”

“He’s a friend. Ain’t nothing you can say in front of me, you can’t say in front of him. I don’t care if you murder people, you can say it in front of him. He’s a friend, and I trust my friends.”

“Okay. Okay. He's a friend.”

“Are we going to talk?”

“Sure. What’s worrying you, skipper?”

“I don’t think you’re transporting legitimate goods, that’s what’s worrying me.”

“Forget it.”

“How’d you get into this anyway? What kind of a racket are you in? Where’d you get the money to buy your own freighter? And a house up in Scarsdale? And all the high living?”

“I haven’t started yet.” He bent to the valise, opened it, and brought out a steel strong-box. He put it on the desk, tapped it. “Take a look. Here’s the proceeds of the cargo I freighted to South America... in cash... American bucks. You want to know how much? One hundred and fifty thousand clams, that’s how much. And ten percent of it, net, after expenses, is mine. Not bad, huh? And it’s going to get better. I’m working on that now.”

“What do you do with it?”

“What?”

“The money.”

“I put it into the safe, and I sit around. Then a phone call comes through. Then a couple of people arrive and take it away. Bad?”

“Doesn’t sound good.”

“It’s going to get better.”

“How?”

“A full partnership, that’s how. You got an ambitious son, skipper.” He moved with the strong-box to the safe. He knelt and began to twirl the dial. We watched him, all of us with our backs to the door. His tone was thoughtful as he said, “Suppose seventy-five thousand of that were mine. Seventy-five thousand dollars a trip. How’s that sound, skipper?”

“Sounds like you’re a thief. Sounds crooked, and crookedness has a way of bouncing back at you...”

A voice said, “It’s bouncing right now.” Before we could move, it came again, urgently. “Don't turn around. Or you catch a load of bullets that I guarantee don’t bounce. Listen to a sample.”

A shot sounded, and the smack of a bullet into a wall. The acrid smell of cordite filled the room. None of us moved. The voice said, “Okay, you down there with the box. Back it up, move it toward me, and don't turn around.”

The voice was a heavy, gutteral, half-whispering rasp; an unforgettable sound.

Frank moved the box back. The voice coached him. “A little more, that’s it, just a little more, nice and easy... okay, fine,”

Frank said, “Can I talk?”

“Talk. But don’t talk loud, pal.”

“I’m talking to my father and his friend. I’m saying for nobody to get excited. People have worked it out. That box is insured. I don’t want anybody making like a hero.”

The voice said. “Smart boy. Stand up.”

Frank rose.

“Okay. Now everybody put your hands on your heads. Fine. Now march forward right smack up against that wall and stay like that. Fine.”

Then everything happened in a hurry. There were five quick shots. Frank fell. The door slammed. The key grated in the lock. Feet echoed in the hallway, running down the stairs.

The old man bent to his son, while I yanked at the door. It didn’t budge. A car started up in the street, and pulled away with a scrape of tires.

“He’s dead,” the old man said. “He’s dead.”

I dialed the phone for cops.

6.

When Detective-Lieutenant Louis Parker arrived, the door was open. I had found a key in Frank’s clothes, poked the other key out, and opened the door. I had gone down and looked around but that was as futile as it sounds.

Parker’s photographers and technicians had done their job, and then they and the corpse and the old man were gone. Parker poked a cigar in his mouth. “What do you think, friend?”

“Murder. Louis.”

“What kind of murder, Pete? A homicide during the commission of a felony, or the other kind?”

“The other kind.”

“But from what you’ve told me...”

“The guy had it done. Palance himself had spoken up and said he didn’t want trouble. The guy had the box, and the key in the door, and three soldiers with their hands on their heads and their noses to the wall. He didn’t have to shoot. Plus.”

“Plus what?”

“Five bullets into one guy. Not one for me or the old man. Coldblooded, premeditated, intentional murder.”

“No question.” Parker said. “You’re a hundred percent right.” There was a knock on the door. “Come in,” Parker said.

Cassidy, a young detective, pushed open the door. He winked hello at me. He said, “Frank Palance was the registered owner of the boat, Lieutenant.” He put his hand into his jacket pocket and brought out a paper.

“What’s that?” Parker said.

“Bill of lading, sir. It shows what the vessel was carrying.”

“And what was that, Cassidy?”

“Rope, sir.”

“Rope? Did you say rope?”

“That’s right, sir. A thirty thousand-dollar consignment of rope.”

I said, “What about that hundred and fifty thousand in the strongbox?”

Parker turned to me. “Did you see it? The money?”

“No.”

“Then how do you know it was there?”

“I don’t. But suppose that boat were carrying, how do you call it... contraband?” I looked toward Cassidy. “Is that freighter big enough to carry additional cargo?”

“Big enough to carry the Statue of Liberty. It’s enormous.”

Parker said, “It’s a theory. Now what about you, Pete? What were you doing down here?”

“Came down with the old man.”

“I know. Why?”

“I know a gal Palance was engaged to. They were scrapping. The old man’s been a friend of mine for years. I went up and talked to him about that. He told me I was talking to the wrong guy, told me he was coming down here to see his son, asked me to come along with him. That’s it.”

“Okay,” Parker said. “Let’s get out of here. Keep available, Pete. Check in with me. Often.”

It was a quarter to eleven when I leaned on the buzzer at Lola’s apartment. She said, “Who is it?”

“Pete.”

She opened the door and I smiled out loud. That girl went from great to greater. She wore ice blue satin, clinging lounging pajamas with the cleavage on top going down to the sash in the middle. She kissed me the moment the door closed behind me, her body softly pressed to mine, her hands around my neck. She didn’t let go. I lifted her and carried her into the living room. She even knew how to be carried, her head hanging, her arms loose at her sides, her body pliant and yielding. I put her down, gently, on a wide divan, and sat beside her. I kissed her because her mouth and her eyes demanded that I kiss her. She sat up and said, “What’s the matter?”

“Matter?”

“Your mind’s not on kissing. You’re not here. You’re somewhere else.” One corner of her mouth trembled. “Cooled off already?”

“Nope,” I said. “Not that quick.”

“Then what’s the matter?”

I dug in for cigarettes, tapped out two, gave her one and lit them. I blew smoke.

She said, “What’s the matter?”

I said, “Honey, you signed a contract with me.”

“Contract?”

“The paper back there at the Lido.”

“That. Look. If I can depend upon you to protect me from Frank, if I don’t have to worry about a broken nose or losing an eye, then you’re worth every penny of that percentage you arranged — which you’ll never get anyway, because that policy’s been switched. I told you.”

“And the ring? And the Caddy?”

“I'll never return them. Believe me, I wasn’t kidding when I said I earned them. And I don’t want you to think I'm a bitch, because I'm not. It’s the first time in my life I ever hung on to anything that somebody wanted back. But nobody’s going to make a monkey out of me. Nobody.”

“Nobody’s going to.”

She raised the cigarette and inhaled deeply. “I’m not as bad as I sound. You’ve got to believe that.” She looked away.

“I do.” I put a finger under her chin and turned her face to me. “You don’t have to worry about Frank any more, ever, all your life. And the ring and the Caddy are never going back.”

A wrinkle came between her eyebrows. “I don’t understand.”

“He's dead.”

Her hand flew to her mouth, pressing it in, distorting it. Her eyes, moving up to mine, held horror.

“You killed him.”

“No. No, I didn’t.”

The horror spread, and now it was fright, shock, bewilderment. The hand fell away from her mouth. I took the cigarette out of her fingers and rubbed it out in an ashtray.

“What happened?” she said.

I told her.

When I was through, the blood was out of her face and her fingers were trembling.

“You need a drink,” I said. “Where do you keep it?”

She pointed at a door. I got up and went to it. It pushed through to a kitchen. A white closet over the washtub opened on many bottles. I poured a double hooker of brandy, brought it to her, made her drink it fast. Color came back to her cheeks. She said, “You... you might have been killed yourself.”

“I might have. Part of the occupational hazard. When I’m working. For a fee. Fee.” I sat down near her again. “That policy begins to take on some importance.”

“But I told you—”

“I know what you told me. You told me. I'd rather have his insurance agent tell me. Or maybe I wouldn’t. Do you know his name?” She pushed fingers at her temples, squeezing in thought. She said, “He told me once. Let me think now.” Then she said, “Keith, or Grant. I don’t know. It's either Keith Grant or Grant Keith.”

“That shouldn't be too hard to straighten out. Where’s the phone book?”

She got off the divan and brought it to me. We stuck our heads together and looked. It was Keith Grant. There was an office and a home. It was too late for the office. I called the home. T he phone rang for a while and then a sleepy voice answered.

“Hello?”

“Mr. Grant.”

“This is he.”

I knocked my voice down a couple of notches. Lola’s ear was at the receiver with mine. I said, “This is Mr. Palance.”

“Frank?”

“No. Frank’s father. Ben Palance.”

“Yes, Mr. Palance?”

“Sorry to disturb you so late.”

“That’s all right, sir.”

“It’s about Frank’s policy, Mr. Grant. He talked about a change in beneficiary, the day he sailed. Something about a young lady, Rose Jonas.”

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Change of beneficiary. He was in touch. Those were his instructions. Yes, sir. Rose Jonas.”

“Thanks,” I said, and hung up.

Lola said, “See?”

Glumly I said, “I see.” I got to my feet.

“Where you going?” she said.

“Work.”

7.

The Raven was more lull of noise than a filibustering Senator. The act on stage was Rose Jonas singing Stardust. I had heard better, but I hadn’t seen much better. She was put together like she was comfortable in bed, the naked part top-heavy, the rest of her, in no underwear, encased in a tight black sequinned gown. She had black hair, pulled around exposing one small ear, the rest of it in black curls over one shoulder. She had black enormous spread-apart eyes, hollows in her smooth dark cheeks, and a loose red passionate mouth. She sold sex right off the floor, every bulge of her visible under the baby spot. I couldn’t much have blamed Frank Palance.

I found Tom Connors. I said, “I’d like to wait for gorgeous in her dressing room.”

“Trouble?”

“Possibly. I hope not.”

“Come on.”

The dressing room was like every dressing room in every trap. A tumbled room with the sweet smell of cold cream and the triple-mirrored table with the lights. I smoked and waited and then she came. She saw me but she didn’t say a word. She picked up a pack of long brown Shermans, lit one, drew heavy and smoked fast. She said, “What are you doing here?” She had a slow deep voice.

I said, “Frank sent me.”

“Who?”

“Frank Palance.”

“Who’re you?”

“Pete.”

“Pete who?”

“Just Pete.”

“Frank sent you. For what?”

“I’m supposed to deliver a message.”

“So okay. Deliver it.”

“He’s dead.”

The brown cigarette stopped halfway up. The black eyes squinted. A red tongue came out of the big red mouth and wet the lower lip and stayed there. Then she said, “You want to talk?”

“Yep.”

“Well, this ain’t no place to talk. Let’s get out of here.”

“I’m with you, Rosie.”

She killed the cigarette. She changed her dress. She slung a mink jacket over her shoulders, picked up a handbag out of a drawer, said, “Come on, Buster.”

We went. By cab. To a tenement on the Lower Fast Side. Allen near Rivington, a ramshackle building that hadn’t been painted in thirty years, the kind with the toilets in the halls. We went through a lobby that stank of ancient rats, turned right, and she stuck a key in the door. She made a lot of noise doing it. She opened the door and we went in. I went first.

It was a dirty old room, part kitchen, part parlor, with a couple of dirty old doors loose-hinged at the far wall. The only modern touch was a telephone stuck on top of a peeling, vibrating refrigerator. I turned to Rose.

Rose had a gun in her hand.

A competent little automatic.

It fit her.

She said, “You wanted to talk. Talk.” She shook out of the jacket and let it fall to the door. She dropped her open handbag on top of that.

“Frank’s dead,” I said.

“How do you know?”

“I saw it in the papers.”

“That’s a lie,” she said. “It happened too late for the morning papers. It won’t hit till tomorrow afternoon.”

I said, “How do you know?”

She smiled. Then the smooth, thick red tongue flicked out again. She looked past me, at one of the doors. She called, “Whisper. Mosey out.”

The door opened and a short fat man came through. He wore pants, nothing else. His belly came up to his chest, covered with hair. His feet were bare and dirty. His eyes were lost in the fat of his face, gleaming like an animal’s, and the gleam was sharper, devouring, more like an animal, when he looked at Rose Jonas.

“Hello, Rosie,” he said. “That’s a cute dress. Is it a new one? I like that dress.”

He said nothing about me, or the gun in her hand, but what he said was said in the buzz-saw voice that was more identification than fingerprints.

She pointed the gun at me. “Ever see this guy?”

Reluctantly, he moved his eyes off her, peered at me and smiled, one front tooth missing. His nose wrinkled. “Sure. He was one of them there, down by Frank’s.”

She came near me. “What's your name?”

“Pete.”

“You told me that. Who are you?”

“Nobody.”

“Open your jacket.”

I opened my jacket. She put her free hand in, searching for identification. I was sorry before I did it. It was like taking taffy from an octogenarian. I grabbed for the gun with my left, and jolted my right fist to her chin. She fell in a snoring heap on the mink jacket. Whisper may have had marbles in his head but every little marble understood the gun in my hand.

“Don’t do nothing rash,” he said. “Don’t do nothing rash, fella.”

“Nothing rash,” I said. “Except maybe spray some of your brains on the floor.”

“Cut that out, mister. Please. Don’t talk like that.”

“Who do you work for?”

“Now, look, mister—”

“You look, pal. You killed a guy tonight. Remember?”

“That ain’t for you to say.”

“Ain’t for me to say?”

“I’m entitled to a judge, and a jury, and a lawyer.”

“Look,” I said, “I want information. You’re not the smartest guy in the world. You’re the guy that shoots a bullet into a wall just to let us know you’ve got a gun, and two minutes later you’re telling a guy not to talk too loud. But try to understand this. Try hard. Either I get information, or you get lead. It happens to guys... resisting arrest.”

“Cop?”

“Private. Okay. The nickel’s in the slot. Let’s have the music.”

“I work for Joe April.”

“How long?”

“A couple of months.”

“You from the Coast?”

“No.” His voice lowered.

“Where?”

“Detroit.”

“What’s April’s racket?”

“I don’t know.”

I didn’t think he was telling the truth, but I wasn’t pressing. I said, “Where’s headquarters?”

“Flamingo Garage. Thirty-first and Ninth.”

“All right. Now where’s your heater?”

He pointed at the open door. “In the bedroom. In the rig.”

“Move.”

I walked with him into the filthy bedroom. His holster was caught around the brass bed-post of an old bed. I took his revolver out and marched him back to the kitchen. I said, “Sit down.”

He sat.

Rose kept snoring on the floor.

I said, “What’s your real name?”

With dignity he said, “Roderick H. Dallas.”

I went to the refrigerator and for the second time that night I called cops, this time Detective-Lieutenant Louis Parker in particular. Rose Jonas was still snoring when the sirens sounded in the street.

8.

I worked it out with Parker. It took a lot of coaxing, but I worked it out. It was a way of pushing through, right to the bottom, quick and with one shove. And it might work. It was better than a raid, and the onslaught of shysters with writs of habeus corpus. And I didn't know these guys, and they didn’t figure to know me. It took a lot of coaxing, but Parker was all cop, and he was keen enough to know it might work, it might push through, all the way, with one shove.

A cab took me up to the Flamingo Garage in fifteen minutes. It was quiet and dark with shuttered windows and a sheet-metal door pulled down. I pressed a bell at the side and listened to the clang inside. A little trap-door opened and a man said, “What do you want?”

“April.”

“Who sent you?”

“Whisper.”

The trap door snapped shut. There was silence. Then a whirring started and the sheet-metal door moved up high enough for me to enter. I went in. The door moved down and closed. The man said, “Come on to the office.”

It was a big barn of a garage with no more than five cars, all fairly new and polished. The guy opened the office door and we went in. It was much lighter in the office. The guy leading me was swarthy, skinny and pock-marked. He wore a sharp, wide-shouldered suit, and a light gray snap brim hat. The man at the desk was different. He was slick, sandy-haired, impeccable in a white shirt with French cuffs, and the initials J.A. embroidered over the heart.

I said, “You Joe April?”

He said, “What’s it to you?”

I said, “I’m in from Detroit. One day. I hustled up to sec my pal, Roderick H. Dallas, commonly known as Whisper. He gave me the okay to you.”

“For what?”

“Work.”

“Now wait a minute. How do you know where Whisper holes up?”

“I’ve known Whisper since he was running around in bicycle stockings. We have frequent phone conversations.”

“All the way from Detroit?”

“I can afford it. And Whisper, he tells me he’s doing pretty good too.”

“Okay. Let’s have the rest of it.”

“Ain’t too much. I’m a little hot in Detroit, so I come east for a rest. I amble up to see my friend Whisper, and he tells me he’s holed up for a while, blasted a guy tonight. He tells me maybe you can use me, so I come here. That’s it.”

He looked me over closely. He said, “You ever heist a car?”

“You kidding? I was heisting cars when Whisper was heisting his diapers.”

“What’s your name?”

“Scotty. Scotty Sanders.”

“All right, Scotty.” He reached for the phone, dialed, waited, said, “Hello? Hello, Whisper?”

You could hear Whisper’s rasp across the room. “Yeah, boss.”

“Got a friend of yours here.”

“Who?”

“Scotty Sanders.”

“Yeah, boss. A good kid.”

The strain went out of April's face. He looked pleased. He wouldn’t have looked as pleased, if he'd known that the muzzle of Parker’s gun was tight to Whisper’s temple.

April tried once more. “Where’s he from, this fancy gorilla of yours?”

“Who?”

“This Scotty Sanders.”

“From my home town. Detroit, boss. Very handy kid.”

“Okay. Stay holed up. You’ll hear from me.” April hung up, nodded at the pock-marked man, nodded at me. “Jack Ziggy, Scotty Sanders.”

We shook hands.

April said, “In a way, I’m glad you came. We’re short a man with Whisper out. You and Ziggy are going to work together. Tonight. Okay with you, Scotty?”

“Okay if the pay’s okay.”

April nodded at Ziggy and Ziggy went out. I heard the sheet-metal door whir open, and then whir shut.

April said, “Sit down, kid.”

“Thanks.” I sat.

“Let me give you the picture, kid. We got a new twist on an old racket. We heist cars to order. We get orders from all over... out of the country, I mean. Mexico, Cuba, South America. They tell us what they want, just what they want. A green Buick convertible? That’s it. A black Caddy sedan? That’s it. Then we send out spotters, get the car we want lined up — and heist it, boom, like that. We touch them up maybe a little bit, and that’s it. How’s it sound?”

“Sounds good enough to me. How’s the payoff? For the little guys, like me?”

He opened a drawer. It held a big blue automatic and a sheaf of bills. He drew out a few of the bills, said, “Here’s five C’s. That gets you on the pay-roll. You play ball... I’ll make you fat. You louse it up... you’re dead.”

Softly I said, “Like Frank Palance?”

“That Whisper’s got a big mouth.”

“It ain’t a big mouth when he’s talking to me.”

“Frank Palance. When a guy gets too big for his britches, he’s through. And with me, there’s no argument, no discussion, no nothing. When you’re through, that’s it. I put him in business — and I put him out of it. Only I wanted to do it myself.”

“I don’t get it.”

He had blue eyes. He screwed them up at me. He said, “You ever figure Whisper for being gun-happy?”

“Not Whisper.”

“Well, he pulled a wing-ding on me tonight. He had orders to pick up Palance and a box of dough and bring them both here to me. He brought the box, but he knocked off Palance, crazy-like. Maybe the guy would have had an out, which I doubt. Never had a chance to find out. Whisper got gun-happy. You think maybe Whisper’s getting a little too nervous for his own good?”

“I don’t know.”

He laid the five bills on the desk. He said, “You see, that’s dough. There’s plenty more. But don’t go flipping your wig, like Palance. He was making a nice hunk of change. But all of a sudden, he wanted in. Instead, he got his head handed to him. Okay, kid. Take your dough.”

I took it, stood up, put it into my pants’ pocket.

The sheet metal door whirred, then whirred closed.

Jack Ziggy came in with the gun in his hand.

April said, “What goes?”

“I went over to check with Whisper, personally.”

“Yeah?”

“No Whisper. No nothing. Lily filled me in on the rest.”

“Who’s Lily?”

“Owns the candy store across the street. They marched Whisper out. Cops marched him out. Marched out Rose Jonas too.” He gestured with the gun. “This guy’s a plant. Strictly.”

April said, “Me and my big mouth. I’m doing this one myself.” He reached into the drawer for the blue automatic.

These were not amateurs. There was no Rosie Jonas holding a gun like a cap pistol. This was a spot, and in a spot like this you’re dead. You’ve got nothing to lose. I jumped him, right there and then, with the other guy holding a gun on me. I jumped him, the blue automatic in his hand. I did a dive as good as Lola Southern, a flat dive, with force, and me and the guy and the swivel chair got tangled on the floor, with Ziggy jumping around looking for an opening.

Ziggy thought he had it.

He let go twice, and killed his boss.

I had the blue automatic in my hand, and I used the body as a shield, and I missed twice, and then a slug caught me in the arm, and then another in the shoulder, and then I didn’t miss. I opened a hole in his forehead, and the blood burst out like a red mask, and he dropped, and then I sprawled over the dead Joe April, and I tried to get up, but I couldn’t...

9.

I sat slanted downward in the cranked-up bed, and I waited for them to show up, Parker and the cast of characters. I had no kick. I’d be out in three days. One bullet had gone clean through my left arm, and that was easy. They cleaned it, and closed it, and that was that. Not even a broken bone. The other one got stuck in a muscle near the lung, and that was lucky too. The lung was clear. They had to probe for that one, and they tell me it got a little nasty. That’s why I was a hospital case. Three days.

I hadn't been able to sleep and a couple of thoughts had bounced around in my head, and then I had sat up and reached for the phone on the little table and I had called Parker, and Parker was bringing them to me.

Now.

I heard their feet in the corridor.

The first ones in were Parker and a long, gaunt, fleshless man. Parker introduced us. Keith Grant. Peter Chambers.

I had no time for pleasantries. I said, “Did Frank Palance’s policy carry a double indemnity clause, Mr. Grant?”

“Yes, sir. It did.”

“Have you got it?” I asked Parker.

“It’s downtown. With his effects.”

“Mr. Grant,” I said. “Who was the beneficiary?”

“Originally?”

“Yes.”

“Fanny Rebecca Fortzinrussell.”

“What?”

“That’s the name, sir. Fanny Rebecca Fortzinrussell.”

“Okay. Then, on the day he sailed, three weeks ago, you got orders for a change of beneficiary. To Rose Jonas. Correct?”

“Yes.”

“Sailing day’s the busiest day. You mean to tell me that Frank Palance was able to get away to sit around to talk with you?”

“No. That’s not a fact. He called me and gave me instructions. I prepared the papers for the change he requested.”

There was a hole there. Big as the socket of a new-pulled tooth. I crossed my fingers. I said, “Did he sign those papers?”

“No.”

No, he said. I blew out a lot of breath. That meant twenty thousand dollars to me. No, he said.

“Was he supposed to sign them?”

“Yes, sir. I had them all prepared. I expected to see him when he returned.”

“Correct me if I’m wrong. But that leaves the policy in status quo. Does it not?”

“Yes, sir. It does.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Thanks very much.”

Parker marched him out, and marched back with Whisper, Rose Jonas, and a uniformed policeman.

Whisper said, “Geez, Mac, they get you bad?”

“They’re going to get you worse, pal. You’re going to fry.”

He had clothes on now, shoes and a shirt and a crumby-looking jacket. “Maybe,” he said. “Maybe. Shysters got tricks.”

“There’s only one trick that might get you off the chair, pal. And I got it.”

“You got it, Mac? You got it for me?” A bit of drool leaked out from a corner of his mouth.

Parker creased his eyebrows. Rose Jonas lit a brown cigarette.

I said, “You gun-happy, Whisper?”

“Not me. Not Whisper.”

“They’re laughing at you, pal. They got you down as a nut. Gun-happy.”

“Who? Who's laughing?”

“Everybody. All the boys. Joe April, Ziggy.”

“You tangled with them, kid. Didn't you? That's how you got the slugs.” He giggled.

Smart Parker. He hadn't told him about April and Ziggy. He hadn't told Rose either. Smart cop, that Parker. He hadn’t told either of them, the giggling Whisper, and Rosie with the cigarette under full control.

“They’re laughing at you, Whisper. They figure you’re washed up. They’re making jokes about you. She's laughing too. Rose Jonas.”

“Not Rosie.”

“She says you’re gun-happy too. She’s making jokes with the boys, she’s even making jokes with the cops. About you, sucker.”

“Not Rosie. Rosie knows I ain’t gun-happy.”

“Shut up,” Rose snapped.

Whisper turned his head to her. “Don’t talk like that, Rosie.”

“Shut up,” she said.

I said to Parker, “Get her out of here.”

Parker motioned to the cop. The cop took her out.

I said, “You’re not gun-happy, are you, Whisper?”

“No, I ain’t. And I don’t like no jokes about it.”

“Rosie’s making the jokes, all over town. You’re a sucker.”

“Sucker, maybe.”

“She talked you into it because it meant loot for her.”

“Loot? How?”

“Frank’s life policy. In her name. Did she tell you?”

“No.”

“She cuts you out of the loot, and then she makes jokes that you’re gun-happy. But you’re not gun-happy, are you, Whisper? You let him have it because she told you to let him have it. Right?”

He said slowly, “Right.”

“Now listen to me, Whisper.”

“Yeah, Mac, I’m listening.”

“You tell the truth, they might let you plead guilty to second. That gets you off the hot seat. It gives you life. Life, there’s always the possibility of parole. She pushed you around, pal. You’re supposed to push back.”

“I’ll push back,” he said.

Parker took him out. There must have been more cops in the corridor, because Parker came back. “Nice work,” he said. “The District Attorney’ll love you.”

“You think it’ll stick?”

“Yeah. All we got to do is keep them apart. After we get his admissions, signed and sealed, hers will come easy. Thanks for a murderer, Pete. How’d you make it?”

“It didn’t budge her when I told her Frank was dead. She knew it. She took me to where Whisper was holed up. She pulled a gun on me before I talked. When she wanted to know how I knew, I told her I saw it in the papers. She knew I was lying because she knew when he got it. How’d she know? Whisper didn’t tell her. Whisper was holed up, and she was working at the Raven. Put that together with the way Whisper looked at her, and the fact that April told me he had specifically ordered Whisper to bring Frank in, not to gun him. You don’t need a machine to add it.”

“Sweet thinking, Pete. Nice work.”

“Miss Southern out there?”

“Yes.”

“Send her in, will you please, Louis? And with her I don't need any other company.”

“Fine, Pete. Good night, and take it easy.”

“Good night. Lieutenant.”

10.

I was alone for a minute, then Lola came in, in a black suit and a high-collar lace blouse and a black beret on the side of her head. She walked on tip-toe, a little wan, a little worried.

“Are you all right?” she said. “Are you all right?”

“I'm fine. Be out of here in three days.”

“Oh, I’m glad. Can I kiss you?”

“Lightly.”

She kissed me. Lightly. It was the beginning of my convalescence.

I said, “Are you Fanny Rebecca Fortzinrussell?”

She blushed right up to the roots of her golden hair.

“Ain’t it the craziest?” she said.

We laughed, together.

“Can you prove it?” I said.

“Do I have to?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“For a hundred thousand dollars.”

“For a hundred thousand dollars I can prove it, and I don’t know if I'd prove it for anything less. You delirious?”

“Practically.”

“How come?”

“Frank Palance know that Fortzinrussell label?”

“Yes he did. Happens it’s my real name. Glamorous, isn’t it. Why?”

“That's the name of the beneficiary of his policy.”

“Only it was changed. To Rose Jonas.”

“Not true.”

“But the guy on the phone. The agent. Keith Grant.”

“He had instructions for a change of beneficiary. He had prepared the necessary instrument, but Frank hadn’t signed it. He was going to sign it, on his return, but he got killed too quick. Which keeps the policy as is, to the benefit of Fortzinrussell. Fifty thousand face, but when you get shot, it’s accidental death, double indemnity, a hundred thousand dollars. Yours.”

There was very little reaction. She said, “I’m not interested in that right now. I’m interested in you. Are you all right?”

“Fine, I told you. I’ll be out in three days.”

She bent to me and her lips brushed my ear. “I love you,” she whispered. “I can t wait.”

“I can’t either, believe me.”

A starchy nurse came in on rubber heels. “I think he’s had enough,” she said. “Every rule has been broken, what with police and things. He’s had enough, Miss.”

“I’ll be around tomorrow, during regular visiting hours,” Lola said. She kissed me again, not as lightly.

The starchy nurse ushered her out.

I settled back in the bed. I mused. I would be out in three days. Nice to be out in three days and have a shining blonde waiting for you. I mused some more. I thought about the first moment I had seen her as my eyes had flicked up from the crap game, and then the ride out to Lido, and the structure of that poised body high on the diving board, and the fingers ripping at the belt of the terry-cloth robe, and the glistening two-tone body, brown and white, brown and white...

She was a lot like me, she was no baby, she’d been around, a lot like me, quick, fast, impetuous, a hit and runner, hit and runner, hit hard and fast, and then run like hell. I wondered how long it would last, Lola Southern and Peter Chambers, but as long as it lasted it was going to go like a rocket, fun and fast, hit and run. I leaned over and opened the drawer of the little table and took out the contract she had signed in the bath-house at Lido. I read it, re-read it, patted it gently, and put it back in the drawer.

It represented twenty thousand solid simoleons.

Love is love, but a man has got to eat.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ