The Big Scorer by Sam Merwin, Jr

The fillers got even more money than they’d expected. That was part of the trouble...

1

Three days after the killing of F. Hubert Fellowes in his porticoed white mansion, set back from Hillside Boulevard, the story was still crowding Cold War news, the Miss America contest and a new local housing project off the front page of the City’s one morning newspaper, The Gazette. Under a big black banner headline that read Five-State Dragnet For Fellowes Killers, it stated:

Thanks to new clues turned up by the police, state and local constabularies over a five-state area have set up an airtight dragnet to trap the murderer or murderers of F. Hubert Fellowes, prominent businessman and philanthropist of this city, who was murdered while alone in his home late last Monday night or early Tuesday morning. Two as-yet-unidentified men, seen speeding away from the murder scene a few minutes after one a.m. on the night of the slaying in a maroon convertible, are the subjects of the search.

Mrs. Barbara Fellowes, widow of the victim and prominent local socialite and clubwoman, returned early yesterday from the summer resort for which she had departed, with her two small children, only last Saturday. Mrs. Fellowes’ return was delayed because she was staying at an isolated Canadian mountain resort and could only be reached by automobile. In a brief interview with Gazette reporters, Mrs. Fellowes said: “I cannot imagine why anyone would want to kill Hubert Fellowes. He was a man without enemies, a man...”

The Thursday noon news-broadcaster over Radio Station WZZQ was punchier. He said, in staccato Winchellesque syllables, “Police interest in the F. Hubert Fellowes murder is focussing on the safe in the late philanthropist’s bedroom, where his bullet-riddled body was found. This safe, concealed behind a Utrillo painting of Montmartre, had been opened and rifled when the body was found by Tony Martello, gardener for the Fellowes estate. To date, police have no clue as to what was taken by the killer or killers. They are giving more and more weight to the opinion that the murder was the result of a carefully planned, professional job, such as the city has not known in years. Every effort is being made to...”

Gino extended a hand and turned the dial. Mambo music flooded the tenement room, whose dinginess was only partially masked by the semidarkness of almost fully drawn yellow shades at the two windows. He said, “How do you like that — ‘Carefully planned, professional job’?” He permitted himself a faint smile of satisfaction over work well done. He was a dark-skinned youth with large, luminous eyes and the grace of a professional dancer — or a coiled snake.

Mike, who was lolling beside Dora on the unmade cot that, with two tables, a battered bureau and two wooden chairs, comprised the room’s total furniture, said, “What I like is that five-state alarm and those creeps in the convertible. Not a sign they’re onto us. What a breeze!”

Gino spoke sharply. He said, “Watch it, Mike. We aren’t out of the woods yet — we’re just into them. The cops don’t Spill everything they know to the papers.”

Arne, his silver-blond hair one immense rat’s nest, spoke up from the chair by the window, where he was trying to get some air. He said, in his slow, stupid drawl, “No cops — I can smell ’em a mile away.”

Dora got up from the cot and pushed uncombed blonde hair back from her forehead. She wore only a bra and panties, bobby-sox and shoes, and her skin shone with sweat. She crossed to the table and picked up one of the packages and said, “Here’s what I like — who’d have thought the old jerk would have a load like this stashed in his bedroom? Once we start travelling, we travel in style.”

“You sure your mother won’t get on your tail, kid?” Gino asked her, for perhaps the fifth time in the three days they had been cooped up in the tenement.

The girl said, unpleasantly, “You’re making me laugh! Ma won’t come off this bender she’s on for another ten days. And then she won’t have the nerve to ask questions. The last time she came after me, she damn near got jailed herself for parental negligence.”

She gave the crisp bills a riffle before laying them back on the table. “No more sitting,” she said. “No more getting them glasses of water, no more burping, no more wiping their snotty little noses. Am I glad!”

“You got a date tonight, haven’t you?” Gino asked quietly. Like the others, he had stripped to a minimum of clothing.

Dora turned on him like a panther. She said, “If you think I’m going to keep that date, you’re out of your mind. I set up this score for you lice, remember? So why do I get stuck with the dirty work afterward?”

Gino slapped her hard across the face. The sudden, sharp sound was shocking in the silence of the room. He said, his voice moderate, “Don’t get out of line now, Dora. If you don’t show up, the people might start asking questions. And we don’t want that, do we? We’re clean so far. We want to stay that way.”

Dora, who had endured the slap without a sound, said to Mike, “You going to let him maul me around, you big goon? You just going to sit there and let him beat me up?”

Mike, the biggest and oldest of them all, sat up straight on the cot and said, “Take it easy, Gino.”

Gino looked at him quickly and with contempt. Then, to Dora, “Sure you set it up — but you didn’t know it was going to be this big. Thirty-two gees — the old guy must have been out of his mind to keep that kind of loot stashed in his home. You’re going to get your share, chick, so relax. But you’d better start eating radishes right now.”

She said, “Drop dead, you louse!” and her blue eyes were smoky with rage. But she reached for the bag with the radishes, alongside the collection of half-empty food cans and bottles on the other table.

2

Gino had a lost feeling under his diaphragm. He knew they were treading water way over their heads. Neither the murder nor the size of the haul had been included in the range of their plans. They were just kids, all of them, kids without connections.

Arne was only seventeen, though he had the face and body of a man ten years older. He sat there by the window, silent, sweating, impassive in his shorts and shoes. An animal, Gino thought, a stupid, unimaginative, unfeeling animal.

Dora was a year older. A smart little tramp, with a boozer for a mother and an unknown father, she had finished high school at sixteen. A little girl with big ideas. The noise she made, munching on a radish, was like the crackling crunch of a tooth extraction. Gino said, “Dammit, can’t you keep your mouth shut while you eat?”

She bared her teeth and made the munching louder, looking at him with eyes of hate. Still sitting on the cot, Mike said, “Get off her back, won’t you, Gino? It’s hot enough in here.”

Gino just looked at him. Mike was his big worry. Mike was twenty-one, a year older than Gino himself. Six months earlier Gino had had it out with him and carved him up a little. Even in the dim light the knife-scar showed, livid under his right ribs. Gino could have taken Dora away from him then, but he hadn’t wanted any of Mike’s castoffs.

Mike was the soft spot. While it was Gino who had killed Mr. Fellowes, it was Mike who had fired the four other bullets into an already dying body. The murder had been necessary, once Fellowes spotted Dora. Gino had done it, if not calmly, at least efficiently, as he did whatever had to be done. There was no call for Mike to go berserk, even if the bullets from two guns in the body must be causing a lot of head-scratching among the cops. That part hadn’t come over the air as yet.

Dora belched and threw the last bitten-off radish-top on the floor. She said, “These things always give me a bellyache,” rubbed her flat tummy above the waistband of her panties and sank back on the cot beside Mike.

Gino wondered how long they were going to have to stay in the hideout, if they could stick it out a bit longer without exploding. It was important they show themselves, a while longer, in their regular haunts, so their absence would not make them a magnet for police attention.

Gino wasn’t worried about the police. Not in this city, this beautifully policed city where big-time crime had not been known for years, this city that was known from Coast to Coast as a “safe” spot for important crime figures. That was the deal — in return for a clean community, the syndicate got a sanctuary. The City was full of criminals, but its crime record was a shining example to other towns of similar population.

What held the four of them to this tawdry tenement hideout was the dough — the thirty-two grand piled in neat stacks on the table against the wall. They didn’t dare leave it alone. Worse, they didn’t dare leave any of the others alone with it. They were stuck.

When they did go out, they always split up by twos — and always so Mike and Dora were not together. It was a laugh. They might as well all have been stuck in the same bathroom. The same dirty, hot, stinking bathroom. Nobody dared unlock the door.

There was a break in the program. An announcer came on with a special news bulletin. He said, “City Police have just reported the finding of the maroon convertible sought over five states in the Fellowes killing. It was located on a side road of Highway 1145, where it had been abandoned by the men seen leaving the scene of the crime. A new alarm has been broadcast over a nine-state area.”

Mike rubbed his red hair and said, “Jeest! How do you like that? Maybe this will make the big brass pay attention.”

“Yeah,” said Arne, flicking a fly off his damp chest.

“Don’t get delusions of grandeur, Mike,” said Dora. “We haven’t spent any of the loot yet.”

“On the nose, chick.” Gino permitted approval in his voice. He looked at his wristwatch, with the flexible gold band that was turning green in the heat. He said, “Four o’clock. Mike, you and Arne take a turn out. And Mike — don’t talk. Listen.”

Mike stood up and yawned and reached for his trousers. He said, with mild resentment, “Why pick on me? Arne’s going too, ain’t he?”

“Right,” said Gino. “But when did Arne ever open his mouth?”

Mike was amused. He said, “You got something there, kid. Come on, Arne.” He gave Dora a poke in her bare midriff, added, “Keep it under control, honey.”

“Bring back some beer,” said Gino. “And pay for it.”

“Ha, ha!” said Mike, closing the door behind him.

3

Dora sat down in a chair, facing the back and straddling it, toward Gino. She said, “Give me a cigarette,” and brushed away the fly, which had transferred its attentions to her from the departed Arne. Gino gave her a limp smoke, even lit it for her.

Dora pushed back her hair again and looked at him thoughtfully and said, “How long is this going to last, Gino?”

He thought it over and shrugged and said, “A few days more — a week, maybe. Why? Piling up on you?”

“Maybe a little,” she said. “Mike’s such a jerk.”

Gino looked at her, reading her as he’d had to learn to read people since he was five years old. He said, “Like loves like.”

For a moment, he thought she was going to spring over the back of the chair and stick the lighted cigarette in his face — or try to. Then her eyes fell away and she looked sulky and said, “Maybe that’s not entirely my fault.”

Gino kept on looking at her for a long, heavy moment. It occurred to him, not for the first time, that Dora was nice — physically at any rate. And she was smart. But he had no intention of breaking down at this late stage of the game.

He said, “Use that damn brain of yours, will you, chick? What busts up every big score, sooner or later? How many of the Brinks’ holdup mob ever got to enjoy that two million bucks?”

“I’ve heard that sermon before,” said Dora intensely. “You’ve got what it takes, Gino — you and me. Arne’s a zero, Mike’s a dope. You and me, Gino — together we could run up a real score.”

“Get smart, will you?” he said with a mixture of patience and irritation. “We duck out with the loot and what happens? Mike starts singing and we’re dead. Besides, I got ideas of my own.”

“How far do you think you’re going to get on eight gees?” The girl dripped scorn. “And who’s going to set up your next score if I’m not in the picture?”

“Eight gees can carry one guy a long way,” he said. “And who wants to go on making this kind of score? We were lucky this time — about five ways. It don’t figure to last.”

“So all right,” she retorted. “So we leave the creeps their cut and take off together. We still got sixteen instead of eight. And I don’t have to stay a baby sitter forever to set them up for you. I’m educated and I can look as good as I have to.”

He studied her and nodded and said, “Yeah, I guess maybe you can, chick. But why me? You know I won’t ever go for a girl who’s had Mike.”

“What do you want — some debutante?” she blazed at him. “You wouldn’t know how to pick up the right fork! Why you? Why not you? You’re not bad looking once a girl gets used to you. Maybe I go for you.”

Gino said, “You can turn that on and off like a faucet. For now, turn it off. Do I have to lean on you again?”

“Try it!” she said. “Just try it, you cheap punk.” She dropped her cigarette on the floor and crushed it under a shoe and went back to the cot and flung herself face down.

4

For the hundred and twenty-first time, Gino went over the Fellowes robbery, which had developed into murder and such an unexpected big take. Dora had set it up. Since she began going with Mike, she had learned to turn her career as a babysitter to profit. At one time or another, during her high-school years and since, Dora had baby-sat in just about all of the big houses on Hillside Boulevard and in the whole wealthy Woodvale district.

With the eye of a camera and the memory of a tape-recorder, she had, on deposit in her brain, exact floor and furniture plans of every house she had worked in. More important, she had trained herself to know what was valuable and what was not, to pick up odd bits of gossip as to which families kept cash on hand and which were going to be away on trips.

When Gino had taken charge of the group, he had taught her how to spot burglar alarms and other precautions against intruders. It was information Gino had acquired two years earlier, in reform school in another state. For he was a young man who had long since forfeited his home. He was a waif, a wanderer, a seeker after a way of life neither he nor the others had ever known.

In short, a punk.

He had come to the City riding a freight car, with two dollars and sixteen cents in a ragged pants pocket, less than a year before. He had known about the City, of course, like every other youth who had ever spent time in a reform school. He had taken a succession of jobs while he looked around and learned the local ropes — bowling alley pinboy, bellhop at the City Hotel, copy boy on the Gazette. None of them had offered him a promise of the future he sought, a future in which Miami sands and fifty-dollar-a-day suites and luminous blondes and Las Vegas gaming tables loomed large.

It was impossible for a local boy to make a good connection. All such contacts belonged to the upper-bracket businessmen and politicians, and these plump citizens had them sewed up tight.

The City was out of bounds.

That was why he had decided on the Fellowes job, when Dora revealed the opening. He wanted a stake to get out of town, enough to set him up in business elsewhere. It had looked open-and-shut. Fellowes’ wife and kids were going to Canada for a month. The old man was going up there with them to spend the first few days. Dora had learned about the safe and got the combination from the younger kid.

They hadn’t expected Fellowes to come back so soon — and they hadn’t expected to find the thirty-two gees in the safe. Fellowes was dead — Gino would never forget the stupid look on his face when he sat up in bed and saw Dora opening the safe. He had turned on the light and said, “Why, Dora, what’s the idea?”

So Gino had shot him. And Mike had fired more bullets into him. And they had taken the dough and let the silver alone.

A perfect job. No one had seen them coming or going. They had the money. In a day or two, a week at the outside, they could make their split and take off. If Mike didn’t do something stupid or Dora didn’t make trouble.

Gino looked at her, lying curled up on her side, breathing softly, innocent as the gold chain with the cross on it around her neck. In the dim light, he could see the red spots beginning to appear on her face. Radishes gave her an allergy.

She had discovered this as a kid, used it to fake measles when she was a kid in school and wanted a few days off. She ate radishes now, before she went baby-sitting. “They feel a lot happier if you look unattractive,” was her logic. “That way, they’re not so afraid of a girl’s boy-friends coming to call.”

For a moment, Gino was tempted to wake her up and say, “Come on, chick, let’s grab the loot and take off.”

But Mike would howl like a banshee and they wouldn’t get far. Gino yawned and scratched his damp chest and sat there, half-listening to the radio, making half-cooked plans toward what he would do when he got out of here.

A long, hot afternoon.

5

It was after five when Mike and Arne came back, sweating out the beer they’d been drinking. Arne had a bag filled with cans of ale and an opener. He put it on the table with the rest of the food and Mike said, as if he’d brought it, “Open up, characters. Fresh from the big yeast cow.”

Dora sat up and yawned and stretched. Mike squinted at her and giggled. He said, “Gawd, honey, you’re a mess.”

Dora gave him a look of contempt, pushed back her hair and spurned the can he offered her. “You crazy?” she said mildly. “I can’t keep a date reeking of beer.” She was covered with spots now, all over.

Arne sat down again in his chair by the window. Except for his daily outings, he might have taken root there. He even slept in it, rather than taking his shift on the cot. He said, “Town’s white hot,” then lapsed into habitual silence.

“What’s cooking — outside of us?” Dora wanted to know.

Mike took over, standing in the center of the floor, a beer-can in one hand, a cigarette in the other. He said, “Arne’s not kidding. We got it from Ozzie himself. Philadelphia, Chicago, Kansas City — even some of the boys from Las Vegas and the Coast. They must be setting up a big shift or something.”

Gino said a sharp, hard word. Here he was, successful boss of a big score, a clean score, a score that would be bound to make any of the boys sit up and take notice of him. And he had no way of letting them know it. He wondered what you had to do to stop being a punk.

The news came on again. There was nothing about the gathering of the criminal clans in the City. There wouldn’t be. More important, there was nothing new on the Fellowes murder.

The announcer was giving the ball scores when the radio went dead. “That damn box!” He went over and banged it. Nothing.

Gino said, “Try the light switch.”

Mike did and again nothing happened. Dora looked at him and said, “Mike, what’d you do with that dough I gave you to pay the electric bill last month?”

Mike opened and closed his mouth three times, like a goldfish. He looked around him, wildly. He said, “Jeest, so I blew it on a filly at Aqueduct. And then forgot to tell you. So what? Have I committed a crime or something?”

Dora just looked at him. She was barely half his size, but she dominated him like a tugboat dominating an ocean liner. Then she said, “I got to use the bathroom to get ready.” She picked up her dress from one of the chairs, and her bag, and went out to the hall. Seconds later, Gino could hear the banging of the pipes as the water came on in the bathroom that served the floor.

A glance at his watch told him it was too late to pay the electric bill until the morning. They could manage without lights — candles or electric lanterns were available at any drugstore. But they needed a radio, not only to keep increasingly frazzled nerves down but for the news broadcast. There was always the possibility that something might break that would affect their security.

It might, Gino decided, even be turned to their advantage. If he could somehow pick up a portable with a police broadcast band... He decided to talk to Ozzie, the fence, wondered briefly what Mike had had occasion to talk to him about during his afternoon outing. Before he had time to ask questions, Dora came back.

She looked about fourteen years old, with her broken-out face, her hair clubbed back and clipped with a rubber band, her little red dress and white patent-leather belt. He got up from his chair and began putting on his own outer clothing — trousers and a red, brown and yellow aloha shirt. He said, “Let’s get going.”

“Hey! What about the lights?” Mike wanted to know. “It’ll be dark in here real soon. You want Big Stupe and me to sit around without seeing each other?”

“It should be a relief — for both of you,” said Gino. “Come on, Dora.”

6

She said nothing till they got outside. Hot as the room had been, the radiations from pavement and sidewalk struck them like a blow in the face, as they emerged from the tenement door. Dora said, “Damn, it’s murder!” Then, “What a birdbrain — can’t even be trusted to pay a lousy bill. Aren’t you afraid to leave him there with Arne?”

“Maybe — but not as afraid as I am of having him outside,” Gino told her. In the late-afternoon sunlight, Dora’s induced-allergy complexion was ghastly.

He waited with her for the bus that would take her to her job. She said, “Any chance of you changing your mind, Gino?”

He shook his head, told her, “Forget it, chick. You and me, we’re going places, all right, but not together — not now. Maybe we can hook up later when we’re both in the clear. But we got too much dead wood hanging to us.”

“You mean Mike?” Dora asked, incredulous. “You could take care of Mike. You already have.”

“Listen,” said Gino. “I’m not after small fry. I’m going to be big. I’ll run my own show. It’s not like the old days. If you want to be big today, you got to be responsible. I freeze Mike out and I got trouble. I kill him and maybe I queer the whole pitch. I’m not connected strong enough yet — not a chance of it in this stinking burg. But if I play what I got smart, I can make it. So can you if you cut loose and get moving. How about it?”

“A girl like me’s got to have a guy to cover her,” said Dora quietly. “It’s a tough pick. She goes for a wrong guy and she’s trimmed like a seal. She holds back from a right one and she’s out in the cold. That’s why I want you. We’d make a team.”

“Don’t you ever get tired?” Gino asked her. “What about Mike?”

“I’ll think of something,” she said. “I’ve got all evening to think of something. How about it if I do?”

“It better be good,” said Gino. “Here’s your chariot.”

“See you at midnight,” she said. Then she was aboard the bus.

Gino walked four blocks to the Alcove, thinking about Dora and her proposition. He wondered what he would do if she did come up with something good. Gino had an orderly mind. He liked to carry through with a plan the way it was set up. Eight thousand dollars was a lot of money. But twenty-four grand was a lot more, even for two people instead of one. If they did get rid of Mike, what about Arne? Arne, the silent, Arne, the cop-smeller, Arne, the stupid — or was he as stupid as he looked and acted? Could anybody be that stupid? Gino wondered. Arne was Mike’s friend. They’d been palling around together since grammar school. It took a lot of figuring out.

The Alcove was air-conditioned. It was a good spot for that part of town. Gino could feel the excitement like a singing high-tension wire, the moment he got inside. The usual noise was missing. The boys and girls were talking low to each other, instead of shouting it up, at this time of day.

There were three characters in one of the booths, beyond the bar. Gino could see them in the back-bar mirror. They were wearing loud, light-weight sports jackets and open-collar shirts. From the neck down, they looked like college boys on vacation.

But not from the neck up. Their faces bore the stamp of their trade. Any colleges they had attended wore bars on the windows. They were part of the big picture, maybe a very small part, but branded major league all the way. Gino regarded them thoughtfully, without envy for once, wondering how long it would take him to be one of them — or better. Eight gees, sixteen gees, maybe twenty-four gees — not big money in their world, maybe, but big enough to get inside if he handled it right.

“Beer, Gino?” It was Murphy, the bartender, with his face like a Swiss cheese. Seven holes in its round, yellow surface — two for his ears, two for his eyes, two for his nose, a big one for his mouth.

Gino said, “Yeah, a beer for now.” Then, nodding toward the men in the booth, “I see we got company tonight.”

Murphy scraped foam off the top with a black wooden spatula. He nodded and put the beer on the bar in front of Gino. Gino said, “Ozzie around today?”

“He was,” said Murphy. “He said he’d be back.” He turned his back on Gino and went down to the end of the bar to wait on somebody else.

Gino stared after him, a sardonic smile on his lips. Murphy usually liked to pass the time of day with him. But with the big boys in town, Gino was just a punk. Murphy didn’t even want to be seen talking to him. Someday, he told himself, Murphy would be dancing to a different tune. Not that Gino intended ever to walk into the Alcove if he ever came back to the City. He’d be occupying the Presidential suite at the City Hotel, the one with the black-marble bathroom. He thought of the lush ladies the bell-captain held on tap for favored customers. During his term as bellhop there, he’d seen enough of them cruising the corridors with their fur stoles and huge shoulder-bags, always carried by the strap in the hand.

He wondered if Dora would raise any hell about that and decided he’d have to take steps if she did. What right, he asked himself, did she have to put in any claim on him? He caught himself and smiled faintly. Hell, he was thinking as if he was already married to her. Married to Dora? That was out, come what might.

Sitting there, alone in the midst of the taut excitement and rising merrymaking around him, waiting for Ozzie, a sudden flicker of panic passed through him, almost making him upchuck his beer. What if he had the picture all wrong? What if Dora’s proposition had been a last chance? What if the others had ganged up on him?

They could have made it easy enough, he thought. Arne was Mike’s pal, Dora was Mike’s girl. What if she’d gotten off the bus after a couple of blocks and cut back to the hideout and the three of them had taken off with the dough? Not for a moment did he kid himself she wasn’t capable of it. Maybe he should have kidded her along instead of playing hard to get.

How could he make trouble for them without showing himself up as F. Hubert Fellowes’ murderer? He had no underworld connections, he had no dough — hell, he didn’t even have a gun. But he’d been right to have Arne throw the weapons into the river after the killing. That way there was no question of a weapon-chase, no ballistics evidence.

Gino got himself back under control. Arne lacked the brains to make such a move, and Mike lacked the cold guts. Dora had both, but she wouldn’t saddle herself with such a pair of creeps. Gino ordered another beer from the nose-lofty Murphy and helped himself to a handful of peanuts from one of the bowls on the bar. He told himself he was getting punchy, dreaming up combinations like that.

He wondered what kind of a plan Dora would dream up to get rid of Mike. Sitting there, he discovered he was not sweating for the first time in days. Time was passing. It was already dark outside. He glanced at his watch, saw it was almost nine o’clock. Where the hell was Ozzie? Gino didn’t want to leave Mike and Arne alone too long in a radio-less, unlighted room. Not Mike, anyway, not full of beer and God only knew what else.

Ozzie came in then, a dumpy, plump, friendly little man with gold-rimmed glasses and a seersucker suit. Gino gave him a sign but he went back and talked to the three big-timers in the booth. He could hear their voices, their laughter, but he couldn’t make out what they were saying. Ozzie was a great one for stories.

After a few minutes, he came to the bar, alongside Gino, and asked Murphy for a napkin to wipe his glasses on. He said out of the corner of his mouth, his voice low, “Boy, it’s hot — too hot!”

Gino got it. He looked down at his beer and rolled a couple of peanuts around the base of the glass. He said, “I’m not selling, I’m buying for a change.”

Murphy hesitated, then nodded as he put his gold-rimmed glasses back on. He said, “The place — half an hour.” Then he was gone.

Greedy little man, Gino thought. Like everyone else.

7

Ozzie was one of the few criminal institutions the City could boast, one of the few it allowed to operate. Ostensibly, Ozzie ran a discount store, one of those semi-converted lofts in which the smart purchaser can pick up anything from a claw-hammer to a five-hundred-dollar camera or a thousand-buck color TV set — at from a third to a half off the listed market price.

Actually, Ozzie was a fence, part of a nationwide string of stolen-goods dispensers with international affiliations. He’d buy anything, under any circumstances, sell anything, ditto — and always at his own price. According to the grapevine, he had a stucco mansion with a swimming pool in Miami, and an apartment on Central Park West, as well as his suite in the City Hotel. That was where Gino had got to know him, during his bellhop hitch. Without Ozzie, he wouldn’t have been able to operate at all.

But to Ozzie, Gino was a punk, now, always and forever. Ozzie had no use for ambitious kids, though he was willing enough to make money off them. The only reason he was allowed to operate in the City was because the big shots insisted on it. Sometimes, when they hit town, they had hot items to dispose of fast. Ozzie was the answer. He never sold in the City what he purchased there. The stuff he picked up went to syndicate outlets in other cities, just as his stock came from them in return. It was safe as houses. And Ozzie was a rich man, getting richer. No crook dared touch him, not with his syndicate protection. Having them on your tail was worse than G-heat.

Gino would have enjoyed parking a knife in his guts.

He had another beer and sipped it slowly. All at once he discovered he was hungry, hungry as hell, but this was no time to eat. When twenty-five minutes were up, Gino tossed a crumpled dollar bill, on the bar and went outside. Three doors down the block, he turned into an alley, passed through a dilapidated wooden door in a high fence and picked his way among ashcans and cartons of other refuse until he reached the back door of Ozzie’s discount store. He rapped twice, and then three times fast, and after a moment the fat little man with the glasses opened up for him. He led the way without talking into a shadowy basement, lit by a single globe hanging from the ceiling.

There he stopped and said, “What the hell do you want?”

“I want to buy a radio,” said Gino. “A portable, with batteries, maybe one with a police band. And a good electric lantern.”

Ozzie mopped a streaming brow with a silk handkerchief. “ ‘I want to buy a radio,’ ” he mimicked, “ ‘and a good electric lantern.’ Hey, kid, you brought me over here for that?”

“I’ve got to have them,” said Gino. He pulled a small, sweat-stained roll of bills from his pocket. “Cash,” he said.

Ozzie raised his hands to heaven — or, more literally, to the pipelined ceiling. He said, “God have mercy on my soul. The City’s hot as a pistol, I’m up to my ears in trouble, and you punks keep bothering me. First your pal Mike, this afternoon, tries to sell me a gold table lighter. Then you want to buy a radio. Why don’t you guys get together and leave me alone?”

“You make money off us,” said Gino. Then, as realization swept over him, “You know Mike and I ain’t friends. Not since that trouble we had last spring.”

“Friends, enemies, who can keep up with you schlemiels? As for money, you’re all peanut operators.”

“Money’s money to you, Ozzie,” Gino told him, getting angry because he was scared. “You’d take a penny profit as long as it was profit. That’s the way your old man raised you.” Inside, he was remembering the only gold table lighter he’d seen recently. It had stood in the living room of the Fellowes mansion. He remembered Mike noticing it, saying, “Hey, that smoke-pot must be worth a coupla hundred bucks.” He remembered himself telling Mike to forget it till they’d tried the safe. Good old Mike — always wrong!

Interpreting Gino’s silence as determination, Ozzie grumbled and said, “Wait here a minute — I’ll see what I got.”

Gino waited, his fears crowding in around him with the shadows cast by the irregular stacks of crates and cartons that all but filled the basement. In the raw dimness of the light, he saw the stenciling on one of the biggest. It read Electric Trains in lampblack letters. He thought back to his own childhood, a childhood of fear and misery at home. He had never had an electric train, except for a cheap one his mother had bought him one Christmas. He’d laid it out under the tree and then his old man had come in loaded and stepped all over it and broken it to bits.

Ozzie came back in the wake of his footsteps, carrying a couple of cardboard boxes. He said, “Here’s your lousy radio,” and pulled it out of the larger box. It looked like a good one. Gino turned it on. There was a brief hum, then it was working. He tuned it, heard an announcer’s voice say, “...are following every possible lead but are not expecting an immediate break in the Fellowes murder.”

He switched it off, noted the short-wave police band, tested it, then turned to the lantern. It was okay.

He said, “How much for this junk, Ozzie?”

Ozzie said, “To you, fifty bucks the pair.”

Gino laid down a twenty and two fives — which left him a ten, three ones and some silver. He said, “Take it or leave it — thirty bucks.” Without waiting for Ozzie’s reply, he picked them up, stuck them back in their boxes and walked out. Ozzie was still screaming at him when he kicked the door shut be him. Something about staying away from Mike if he wanted to be smart.

I’m smart, okay, he thought.

8

Arne let him in. Gino looked around, saw the big dope was alone. He put down the radio, got the lantern out and turned it on. Then he said, “Where’s Mike?”

Arne said, “Mike went out. He got thirsty.”

Gino sat down and looked for the money and counted it in the light of the lantern. It was all there — thirty-two grand. Then he turned the lantern on Arne and said, “When you and Mike went out today — did he sell something to Ozzie?”

Arne nodded. He said, “We had no dough for beer. Mike sold a lighter — a gold lighter.”

“You ever see that lighter before?” Gino asked. Arne nodded. Gino said, sharply, “Where’d you see it?”

“Fellowes’ house,” was the reply. “Mike got ten for it.”

“If the damned fool hadn’t played the ponies, he’d never have had to sell it. If he’d had the brains of a gnat, he’d never have stolen it. I told him not to take anything out of the Fellowes house.”

Arne shrugged, nodded at the radio, said, “This one’s better than the old one.”

“Maybe you think I should have got a hi-fi set?” snapped Gino. Sudden awareness that they hadn’t gotten away clean with the big score, thanks to Mike’s dumbness and greed, frightened him. Frightened, he was sore and getting sorer. He wondered what the big jerk was up to now? All they needed was for him to get drunk and start bragging — or get into a fight and get picked up. Gino cursed Mike, Ozzie, all of them.

Arne said nothing. He just sat there in his chair by the window and listened. Gino tried to eat some cold canned chili, gave it up when his stomach began heaving. The sweat on his forehead was cold.

After a while, Mike came in. He had a bag with a bottle in it under one arm and a silly, drunken grin of triumph on his face. The grin stayed when he saw Gino and the portable and the lantern. He said, “Well, well, look what you brought back! Mam-bo — mam-bo!” He snapped his fingers and rotated his hips in time to the music.

“Why’d you steal that lighter, Mike?” Gino asked.

“What’s it to you?” Mike countered. “I did it, didn’t I? And I got paid off for it, too. What the hell!” He pulled the bottle of whiskey from the bag, uncapped it and took a long swig.

Gino’s first impulse was to give him a going over, try to beat some sense into him. But he didn’t want a row — not in a warren like the tenement, especially not in hot weather with all the windows open. He said, “Go ahead — get stewed. You’re more use passed out than you are conscious.”

Mike glowered at him and lifted the bottle as if to swing at Gino with it. He gave no sign of noticing the spring-blade that had suddenly appeared in Gino’s hand. He returned the bottle to his lips and took another swig. He had to fight to keep it down. Finally, he collapsed across the cot and, minutes later, murmured, “Wake me up when Dora darlin’ gets back. Wake me up when Dora dar—”

“We heard you the first time,” Gino cut him off.

He hoped Dora had a good plan. They were going to have to get out of town fast — and do something about Mike first. In another twenty-four hours, he’d do something to queer the game for all of them. The guy simply didn’t have the stability to stay with it.

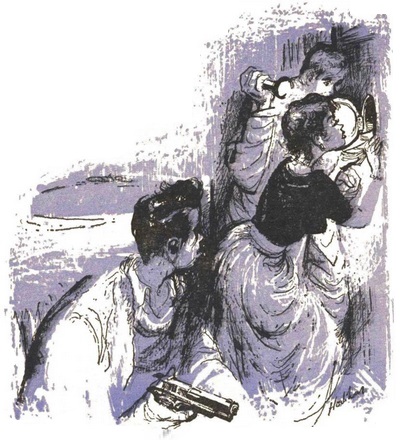

Dora slipped in at ten minutes of twelve. She looked at Mike, lying asleep on the cot, still holding the bottle. She looked at Arne, at the portable radio, at Gino. Then she said, “What in hell’s been happening around here? The block is full of cops.”

Gino was on his feet without knowing how he got there. So was Arne. Arne said, “I knew it. I can smell ’em.”

“Where are they?” Gino asked the girl.

She said, “Still a dozen doors away. They’re making a house-to-house. I think they’re getting warm. How come?”

“Your friend Mike,” Gino said bitterly. He told her about the lighter.

Dora was silent a moment. Then she said, “We got to get out of here quick. If they find us with that loot...”

“Right,” said Gino, “but what about him?” He nodded at Mike.

All at once, Mike was sitting up. “Yeah,” he said thickly, “what about me? If you think you’re going to take a powder now and leave me holding all the sacks you’re out of your mind, all of you. So maybe I made a mistake. I did my share on this sting.”

“Any ideas, Dora?” Gino asked softly.

“Maybe,” she said.

Mike advanced on Gino. He said, “You think you’re such a Goddamn Napoleon, trying to boss the show. You couldn’t boss a chicken-yard, you little punk. You don’t have the guts to pull anything now. I’ll cut you down to your shoe tops. I’ll—”

He stopped talking suddenly. His eyes rolled upward and he crumpled to the floor. Dora was standing beside him, holding the portable. One of its corners was crumpled in.

Gino said, “Nice work, Dora. But we got to make sure he won’t come to and talk.”

Arne advanced ominously into the beam of the lantern. He stood between Gino and the fallen Mike and said, “None of that. Mike’s my pal.”

“He’s your death-warrant if you leave him here,” said Gino.

“Knife,” said Dora, snapping her fingers at Gino. In the shadows, Gino could not see her face. All he could see was her small white hand, outstretched, waiting. He threw her the knife.

Before Arne could turn, she had it open and into him, right through the kidney, up to the hilt. He made a sodden, gasping sound. She pulled it free with a wrench, jammed it into his back, higher up. There was a shrill scrape as it glanced off a rib, then it was through. Arne fell forward across his pal.

Gino picked up the portable and hit Mike hard in the temple, twice. The second time, he felt the bone crumple. He wiped off the grip and stood erect, warily. But Dora was just finished wiping the blade of the knife. She snapped it shut and handed it to him. “Come on,” she said.

The money was in three packets of ten $1,000 bills each, two more of ten $100 bills. They divided it swiftly, gravely, wordlessly. Gino put his half in his pockets, Dora stuffed hers in her handbag. They left the lantern and radio on behind them. Let the cops figure it out — they’d have a ball with it. Gino locked the door carefully behind them.

A cop looked them over at the end of the block. He said, “Where do you think you’re going?”

Dora blasted his head off. She said, “If you must know, officer, we’re on our way to New York to start a new Jelke Ring. We got big plans. Maybe you’d like to come along with us — protection, you know. You’d run up a lot better score than you can here, bothering a girl whose boy-friend is walking her home.”

The cop shook his head and said, “Kids!” and let them through.

When they were safely past him, Gino said, “I’m handing it to you, Dora. You’re going all the way — you and me. Was this the plan you worked out for us?”

“Not exactly,” she said, “but it seems to have done the trick. Let’s get the hell out of town.”

“How?” said Gino. “They got a lot of cops out — not looking for us, maybe, but if they nail us with this loot...”

“How do you think?” said Dora. “We walk. We walk to that motel on the main highway. We tell them we got ditched by our pals. We take a room. Tomorrow, we make some contacts there and get a lift with a family. Leave it to me. By tomorrow night, we’ll be a thousand miles away.”

“I’m sold,” said Gino and he meant it. By the street lamps, he could see that her complexion was almost clear. Put her in decent clothes, put him in decent clothes, and they’d be a good-looking couple. They’d be welcome anywhere. They walked on past the factories and the houses got further apart. Gino said, “It’s a fine night for singing.”

“You can say that again,” said Dora. “Those two so-and-so’s were driving me bats. We start clean, you and me?”

“We start clean,” said Gino. Right then he was as close to being in love as he had ever been in his life. This was a girl in a couple of million, a girl who could kill when she had to, yet who could make respectable folk trust her. Some baby-sitter — some baby!

They swung hands in the moonlight, like a couple of kids at the beach. They could hear the locusts chirruping and zinging in the stretches of grass alongside the road. They couldn’t hear the big yellow Cadillac creeping a hundred yards behind them with only its parking lights for guidance. They weren’t even aware it was following them, had been following them all the way, until it drew alongside them and a voice said, “These your pigeons, Ozzie?”

Ozzie replied, “That’s them.” And, to Gino and Dora, “Come on in, kids. You look like you could use a lift.”

Gino felt like something on a slow motion film. Time seemed to have braked down to a creep. He seemed, to himself, to take minutes to recognize the three sport-jacket sharpies from the booth at the Alcove. He wanted to break and run, run until the world was behind him like a bad dream — but the snout of the submachine-gun pointed at him from the rear seat held him as fixed as if he were an insect held to a piece of card by a pin.

He tasted copper at the base of his tongue — he tasted paralyzing fear. Yet, as he followed Dora wordlessly into the car, he didn’t even know why he was afraid. He only knew he was.

They searched him, coldly, impersonally, as they searched Dora, with regard neither for modesty nor her quickly checked gasp of outrage. Ozzie was polite about it. He said, “Sorry, girlie, but we got to be sure.”

They took the money away from them, took Gino’s knife and Dora’s handbag, then sat them side by side in the rear seat, where the man with the submachine-gun covered them. As they got the car under way, still moving out of town, Ozzie leaned over the back of the front seat and shook his head at them paternally.

He said, “You gave us a bad time, kids. You really had us scared there for a few minutes. We lost you right after you cleared the block and didn’t pick you up again until a couple of miles back.”

“Stop twisting the knife,” said Gino. “Take the dough, Ozzie, and let us go. Why get on our backs just because we made a big score?”

Ozzie chuckled and said to his companions, “Score? Get that — they don’t even know the score.” Then, to Gino and like a teacher to a very stupid pupil, “Kid, it’s all a matter of who you score on. I guess it didn’t enter your fat little heads there had to be a reason for Fellowes having that kind of dough in his house.”

“Why should it?” Gino was defiant. “What’s it to you?”

Again Ozzie found him funny. So did the others this time. They didn’t actually laugh, but their chuckles reverberated inside the big car. Finally, unable to stand the tension, Gino shouted, “Come on, what’s the big boff?”

“The boff is,” Ozzie said owlishly, “that Hugh Fellowes was the payoff man for the syndicate. That dough you lifted was syndicate money. You punks had the whole organization walking on its heels. Until your pal Mike walked in with that lighter this afternoon, it could have been foe Blow as far as we knew. We called a meeting and decided to let the cops handle it for us, and then you walk right through them, you and the girl. A lucky thing we were hanging around.”

“Not lucky,” said one of the sports jackets. “Just insurance.”

Gino felt himself begin to tremble. He was up against something he couldn’t hope to get through. He didn’t know what irony was but there was bitterness for him in the thought that this job, that was to open the syndicate door for him, had put him forever beyond the pale.

He heard Dora ask, as if from a long way off, “For God’s sake, what are you going to do to us?”

And he heard Ozzie reply, without raising his voice, “What do you think, girlie?”

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ