“Pretty swank,” Ann said, as I walked her toward the Cigarette.

“I even got us a driver for the night,” I told her, so she wouldn’t spook when I opened the back door for her.

“And got all dressed up, too,” she tossed back, making an approval-face at my dove-gray alpaca suit. Michelle had made me buy it before I went hunting for the man who’d changed my face with a bullet. It had cost a fortune, but everything she’d said about it was right. Maybe it didn’t transform my appearance, but it sure answered any questions about my financial standing.

Flacco was behind the wheel, Gordo in the front passenger seat. Neither of them said a word, looking straight ahead. As soon as they heard the door close, they took off, slow and smooth. The big SUV rode like a taut limo.

“Do you think—?” Ann started to ask, before I cut her off with a finger against her lips.

She nodded that she understood. Flacco and Gordo had end-played me perfectly. Anytime a man offers to back your play, you’re cornered. So we went through this whole elaborate game where I’d tell Ann they were just hired for the night and they’d pretend they were really worried about me . . . instead of Gem.

When Gem hadn’t even asked me where I was going, I knew I was right. I didn’t blame them for it. They were with her, not with me. She wouldn’t ask them to spy on me—besides anything else, it would be a real loss of face. But if they decided to ride along on their own, well . . .

Flacco docked the Cigarette like it was a boat, backing it into a narrow slot between two other cars only a few yards from the front door of the joint. Once in, he moved forward so we could open the back door, making it clear that he’d be ready to leave as soon as we were, and that we wouldn’t have to look for him when we came out.

I jumped down, held out a hand for Ann. She wasn’t wearing a streetwalking outfit, but her burnt-orange sheath was slit so deep on one side that it opened almost to her waist as she stepped down. A beret of the same color sat jauntily on top of long straight black hair that fell to her shoulders.

If there was a doorman at the club, he stayed invisible. Two-fifteen in the morning; the place was moderately full, most of the attention on an angular brunette in a classy blue dress. She was singing “Cry Me a River” into a microphone that looked like it was out of the forties. The mike had to be a prop—the sound system was Now and Today all the way, draping itself over and around the crowd without a hint as to speaker location.

The waitresses all wore French-maid uniforms with only a moderate amount of cleavage. This wasn’t a joint for jerkoffs or gawkers—players were expected to bring their own.

I ordered a bourbon-and-branch, told her not to mix them. Ann asked for a glass of white wine.

“You like her?” she asked me, making a little gesture with her head in the direction of the singer.

“She’s no Judy Henske.”

“Who is?”

“You know her?” I said, surprised. Judy’s river runs real deep, but it doesn’t run wide.

“I know her work. I caught her in L.A. Twice. She’s . . . amazing. What’s your favorite?”

“ ‘Till the Real Thing Comes Along,’ “ I told her.

“Amen,” Ann said, holding up her glass.

The girl in the blue dress finished her set, walked off with a wave, glowing in the applause.

“Pretty slick, huh?” Ann said.

“What is?”

“That girl, she’s one of Kruger’s.”

“A hooker?”

“A ‘performer’ is what he’d say. All his girls are stars. They want to be actresses, Kruger gets a video made, sends it on the rounds of studios. They want to be singers, he’s got a place for them to perform. And he’s got an agent, a legit one, handles their careers.”

“It’s a scam, though, right?”

“It is and it isn’t. That’s the secret of how he stays on top. Is that girl who just got off the stage going to get a recording contract? I don’t think so. But this town is loaded with great musicians who never get studio time, just work the clubs, building a following. And everybody knows that, so . . . is it really a scam? She is working.”

“And the movie girls? Where do they end up? In porno?”

“Some do,” she said, seriously. “There’s all kinds of porn, some of it real high-end. Kruger wouldn’t go near the ugly stuff. Wouldn’t let any of his girls do it, either.”

“You sound as if you admire him.”

“I admire anyone who knows how to work a system. That’s what I’m trying to do.”

“With the pain-management thing?”

“Yes. But now’s not the time to talk about it.” She turned to the hovering waitress, handed over one of her poker-chip business cards and a folded bill. “Would you please tell Kruger that my man would like to buy him a drink?” she said, smiling sweetly.

The girl in the blue dress was just starting another set when the waitress came over, bent down, and whispered something in Ann’s ear.

“Let’s go,” she said to me.

I followed her as she made her way between tables, heading for a horseshoe-shaped booth in the far corner. When she stopped, we were standing before a man seated at the apex of the booth, a line of girls stretching out on either side. He was a mixed-breed of some kind. Small head, dark-complected face with fine features and very thin lips under a narrow, perfectly etched mustache. Dark hair worn very close to his scalp, tightly waved. He was draped in several shades of off-white silk: sports coat, shirt, and tie. A two-finger ring on his right hand held a diamond too big to be fake.

“Well, Miss Ann,” he said, just a trace of Louisiana in his voice.

One of the black girls on his left laughed at the crack. I kept my face flat, as if I hadn’t gotten it.

“Kruger,” is all Ann said.

He made a little gesture with his diamond. Every woman to his right stood up and walked away.

Ann slid in first. I had to look past her shoulder to see Kruger, who turned his back on the girls to his left and squared up to face us.

“So?” he said, smiling just enough to show a razor-slash of white.

“This is Mr. Hazard,” she said. “He wants to talk to you.”

“Why didn’t you simply come yourself?” he asked me.

“You don’t know me,” I said. “I’m nobody. You’re an important man. It wouldn’t be respectful to just roll up on you, unannounced.”

He measured my eyes to see if I was juking him.

“What is it that you do, Mr. Hazard?”

“I find people.”

“Yes. Well, you found me. And . . . ?”

“I’m looking for a girl. A teenage girl. Runaway. She’s—”

“Oh, Miss Ann here will tell you, I wouldn’t have anything to do with—”

“I know,” I cut him off. “The thing is, I’m not the only one who’s looking. A couple of the other people looking, they came to you.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes. And it’s them I’m interested in.”

He shifted his small head slightly. Said, “I didn’t think you liked men, Miss Ann.”

“Some men,” she answered him, levelly.

“You’ve got game,” he said. Approvingly, as if he was complimenting a kid on the basketball court.

“I’m straight-edge,” she told him.

“I don’t think so, Miss Ann. You’re all curves, girl.”

Ann twisted her mouth enough to acknowledge the barbed stroke, said, “Something for something.”

“What have you got?” he asked me.

“I wouldn’t insult you with money. . . .” I let my voice trail away, in case he wanted to disabuse me of that notion, but he just sat there, waiting. “I’m out and about. A lot. I hear things. I could run across something that might be valuable to you. If I did, I’d just bring it. No bargaining, no back-and-forth, I’d just turn it over.”

“You must be . . . an unusual man, I’ll grant you that. I’ve never seen Miss Ann here with a man before. Are you and she close?”

“Is that what we can trade for? The rundown?”

“Hah!” he snorted delicately. “That was just idle curiosity, Mr. Hazard. What is your first name?”

“B.B.,” I said.

“As in King?”

“No relation.”

“Maybe it stands for Big Boy,” a blonde on his left said, giggling.

Kruger turned slightly in her direction. He didn’t say anything. The other girls got up.

“I . . .” the blonde girl appealed.

Dead silence.

She slid out of the booth and walked away.

Kruger leaned forward slightly. “It’s always difficult to determine what something is worth to someone else. A man like you, if a fly landed on the table, you’d probably ignore it. But if someone paid you, you’d slap your hand on that same table and crush it. The fly isn’t worth anything, do you follow me? But your time is.”

“Sure.”

“My time is valuable as well. And right now I’m afraid I can’t spare any of it. I’ve been quite preoccupied with this problem I’ve been having.”

“Yeah?”

“I am unsure as to the . . . dimensions of this problem, to be frank. But one aspect of it stands out rather clearly. He calls himself Blaze,” Kruger said, shifting his glance to Ann.

She nodded at Kruger. Dropped her hand to the inside of my thigh, squeezed hard enough to get my attention, said, “Some other time, then,” and twitched her hip against me to tell me to get up.

I held out my hand. Kruger made a “Why not?” face and shook it.

Flacco and Gordo dropped us off on a quiet block in the Northwest. The Cigarette purred off into the night. We got into Ann’s Subaru.

“I’ve got to go change,” she said. “I’ll tell you all about it there.”

She hung the burnt-orange sheath carefully on a padded hanger, put the black wig on a Styrofoam head, and sat across from me. She crossed her legs as casually as if she’d been fully dressed.

“You can smoke, if you want,” she said.

I made a “Thank you” expression, fired one up, and put it in a heavy crystal ashtray.

The smoke rose between us.

“You’re not an impatient man,” she finally said.

“It never changes anything.”

“Yes, it does!” she whispered harshly. “Me, I’m impatient. Tired of waiting for the government to do the right thing. You know my name. Do you know what it means?”

“Yeah, I know what ‘anodyne’ means,” I said. “I just look stupid.”

“I didn’t mean to offend you.”

“I don’t think you could. We’re just talking about a different kind of patience. You ever been on a flight where the take-off’s been delayed? You know, you sit out on the tarmac for an hour or two, you know damn well you’re going to miss your connection, and the pilot comes on the PA system in that fake down-home accent they all use and says, ‘Thank you for your patience.’

“Some people get real angry at that. I don’t. That’s the kind of patience I have. When I got no choice, I wait. When it’s smarter to wait, I wait. But it’s not a religious thing. I don’t think people should wait for what’s theirs.”

“Like civil rights?”

“Or revenge.”

“I’m done waiting,” she said. “There’s a new drug, Ultracept-7. It’s only been out a few months. Another form of morphine sulfate, but this one’s supposed to be the most potent of all.”

“I never heard of it.”

“Why would you? But you’ve heard of Paxil, right? And Zyrtec, yes?”

“Yes.”

“Anyone who’s ever watched TV has. Some drugs get advertised very heavily. Because there’s a big market for them. Anti-anxiety, impotence, allergies, baldness—lots of competition for those dollars. But pain? There’s no competition. Not much point convincing you to ask your doctor for a certain kind of medicine when it’s the dosage that’s your real problem.”

“This new stuff . . .” I put out there, to try and stop a rant-in-progress.

“It’s sensational,” she said. “Maybe ten times as potent as anything out there now. A tiny bit goes a real long way. But that’s not what’s so great about it. What’s so great about it is that I know where there’s going to be a lot of it . . . a whole lot of it.”

“And that’s what you want.”

“That’s what I want. It’s got a much longer shelf life—much deeper expiration dates—than anything else out there. I get enough of it, it could last for years. Enough time for things to change, maybe.”

“I already told you—”

“I know. And here’s what Kruger was really telling you. There’s a crew, nobody knows how big, moving on working girls.”

“Trying to pull them?”

“No. They’re not pimps. They sell insurance. Operating insurance.”

“What tolls are they charging?”

“Nickel-and-dime. Literally. They must be crazy. Even if they got every girl in Portland to pay, at twenty bucks a night, how much could they be making?”

“I don’t know. But whatever they make from a lame hustle like that, it’s all gravy.”

“It’s not a hustle,” she said. “The one who calls himself Blaze? He cut two different girls. He’s got a white knife. Supposed to be so sharp the girls didn’t even know they were cut until blood started spurting all over the place.”

“He cut them for not coming up with twenty bucks?”

“Yes. And he may have done more. He told one girl he was going to fire her up, for real. Showed her a spray bottle, said it was full of gasoline. Said that’s where he got his name. Scared her out of her mind.”

“How come the local pimps don’t—?”

“I don’t know what it’s like where you come from, but it isn’t an organized thing here. Not many stables. A lot of girls freelancing. And for most of them, their pimp is their boyfriend. Probably even another addict like they are. Nobody’s exactly patrolling the streets looking for punks with knives.”

“So why does Kruger care? They cut one of his girls?”

“No. At least, not that I ever heard about. But nobody can be sure these guys can tell who’s who, and it’s got everyone nervous. It’d be good for his profile if he did something about it, anyway. His game is that he looks out for all the working girls.”

“You know anything else about this Blaze guy?”

“White. Young guy, but not a kid. Tattoos on his hands. Nobody got a close enough look to see any more than that.”

“His car?”

“No.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“Not even a week.”

“And two girls cut already?”

“At least.”

“There isn’t much chance of catching a guy who operates like that. Nobody can watch all the girls all the time.”

“I know how to do it,” she said. “Let me show you something.”

I was sitting at the kitchen table in Ann’s hideout, a streetmap of Portland spread out in front of me. Ann’s hand rested casually on my shoulder. Every time she leaned forward to point out something, her breast casually brushed my cheek. Thewhole thing would have been a lot more casual if she’d had any clothes on.

“One girl was here,” she said, tapping a street corner with a burnt-orange fingernail. “The other was . . . here. And he confronted other ones here, here, and . . . here. You see it?”

“A triangle.”

“Right. And not a big one.”

“He doesn’t have to be operating from inside the triangle. But it makes the most sense.”

“Because he doesn’t have a car?”

“I don’t know about that. But . . . yeah, that could be it. If those tattoos are jailhouse, it probably is.”

“Why would an ex-con be more likely to—?”

“Pro bank robbers don’t do Bonnie and Clyde crap anymore. It’s still hit-and-run, but you don’t run far. Best way is to have a place to hole up real close to the bank. Just put a little distance between you and the job, then go to ground. And stay there. Disappear. The longer the law looks, the farther away they think you got. Sounds like the way this guy is playing it, too.”

“He would have learned that in prison?”

“Sure.”

“It doesn’t seem . . . I mean, it’s like a trade secret, right? Why would anyone give away information like that?”

“Couple of reasons. In prison, talking is one of the major activities. And you want to be as high up on the status ladder as you can get. There’s always old cons doing the book who’ll—”

“Doing the book?”

“Life. Some older guys, they like the idea of being mentors, pass along what they’ve learned, teach the techniques. And not just the pros. The freaks do it, too.”

“Freaks?”

“Rapists, child molesters, giggle-at-the-flames arsonists . . .”

“What ‘techniques’ could they have?”

“Why do you think so many ex-con rapists use condoms? So they won’t leave a DNA trail. Or why so many ex-con child molesters marry single mothers? Or why—”

“I get it,” she said, repulsion bathing her voice.

“This guy learned about shaking down street whores from somewhere. And about having a place close by to duck into. But whoever told him about ceramic knives left something out.”

“What’s a ceramic knife?”

“What he’s using. They’re not made from steel, they’re made from glass . . . like the obsidian knives the Aztecs used a long time ago. Glass takes a much sharper edge than any metal could. Ceramic knives come in black, too, but steel doesn’t come in white, see? So, if the word’s right about a white knife . . .”

“It is,” she said, confidently.

“Okay, then that’s how we play it. Thing is, ceramic knives aren’t just made of glass, they can also break like glass. They’re great for kitchens, but you wouldn’t want to fight with one.”

“He’s not doing any fighting.”

“That’s right. They’re for slashing, not stabbing. But it’s what he carries. And if he has to use it against someone who’s got a blade of his own, he’s going to come up short . . . unless he’s very good with it. That’s the problem with prison knowledge—there’s no way to really check it out until you make it back to the bricks. Inside, everybody’s fascinated with knives. A good knife-fighter can get to be a legend in there,” I said, thinking of Jester the matador, a million years ago. “And a good shank-maker can get rich. So maybe somebody was talking about how ceramic knives are the sharpest thing going. This guy was listening. And when he got out, that’s the first thing he bought.”

“Or maybe he . . .”

“What?”

“Maybe he wasn’t talking with knife-fighters at all. Maybe the prisoners he was talking with, like you said before, their experience was in terrifying people.”

“Or torturing them, yeah. There’s a school of martial arts that concentrates on fighting with edged weapons. Filipino, I think. Or maybe Indonesian. But they teach offense and defense. Meaning, the other guy’s got one, too, see? It’s for a culture where they don’t have a lot of guns. Prison’s like that, but Portland’s sure as hell not. You probably nailed it, girl. He wasn’t learning from pros, he was learning from freaks. I’ll bet that’s why he went with white. He wants people to remember him.”

“Do you think I’m right about the other thing, too? That he has a place inside the triangle?”

“I do. It scans like a guy just out of the joint, looking to build up a little stake before he tries something bigger. But there’s a few things I’d need to know.”

“What?”

“Housing inside that triangle. Is it expensive?”

“Nothing’s all that cheap in Portland, especially with all the gentrification going on. Neighborhoods that used to be skid row are fashionable now. But right in here,” she said, tapping the spot on the map, “there’s a couple of buildings tabbed for renovation. You know what that means.”

“Yep. Okay, you said the knifeman was with a crew, nobody knows exactly how big. Where’d you get that?”

“There’s at least one more. A black guy. Even younger than the guy with the knife. He’s collected from some of the girls.”

“Any more than him?”

“Not that I know about.”

“All right. But even if they’re holed up close, in one of the squats, that doesn’t solve it. I can’t go door-to-door without tipping them. And I can’t Rambo a whole building by myself.”

“But if you followed him . . .”

“Sure. But what’s the odds of me being in the exact spot where he—?”

“Pretty good,” she said, putting both arms around my neck and pulling herself against me, “if you have the right bait.”

It took us the better part of the next day to get the four different cars in place. If Flacco and Gordo were getting a little tired of playing rent-free Hertz for me, they kept it off their faces. But since they pretty much kept everything off their faces, I didn’t have a clue.

By the time we were done, we had the yellow Camaro, the black Corvette, a blue Ford F150 pickup, and a clapped-out eighties-era Pontiac in red primer all within a two mile radius of where Ann was going to make her stand.

“You sure you want to do this?” I asked Flacco.

“Why not?” He shrugged. “What’s the risk?”

“It’s not that. It’s . . .”

“What?” Gordo tossed in. “What’s up with you, hombre? This is just business, right?”

“I don’t know,” I told them, honestly. “I’m getting paid. But the guy who’s paying me, he isn’t paying for this, understand?”

“You double-backing on him?”

“I might,” I said. “If he turns out to be what I think he is.”

“I still don’t see what’s the problem,” Flacco said.

“Look . . . I don’t feel right about . . . this. You guys, you’re doing things for me out of friendship, right? But I’m getting paid. I’d feel better if I was—”

I caught Gordo’s look, nodded, and swiveled my head to bring Flacco into it, too. “See what I mean?” I said to them both. “You’re insulted if I offer you money, but . . .”

“We like you, amigo,” Flacco said, his voice soft. “But this isn’t about you, okay?”

“Then what—?”

“It’s about Gem, ¿comprende?”

“No,” I said, flatly, squaring up to face him. Glad to finally be getting it on.

“She didn’t ask us to do anything,” Flacco said, hands extended on either side of his face, palms out, as if ready to ward off a blow. “But we know how you and her . . . and . . . we’re with her, you see where I’m going?”

“Yeah. But I don’t even know how it is between me and Gem. So you shouldn’t be—”

“That’s not our business,” Gordo said, quickly.

“But you just told me—”

“Gem, she wouldn’t want nothing to happen to you. We don’t know what you’re doing. From what you say—what you say now—maybe she don’t know what you’re doing, either. Don’t matter to us. You know how it is with women. You don’t have to be with them for them to be with you.”

I didn’t say anything, listening to the quiet of the big garage, trying to decode what they were telling me.

“You know a guy . . . a cop, named Hong?” I asked them.

If anything, their faces went even flatter than usual. When neither of them said a word for a long minute, I tossed them a half-salute and walked out.

I made the first run just before eleven that night, driving the Corvette. Ann was standing in front of a vacant lot, about a third of the way down the block from the corner where some working girls were showing their stuff. Her location would make sense to the watcher that we hoped was on the set: close enough to the action, but not right in the middle of it. Just about right for a new girl who didn’t have a pimp with enough muscle to clear a prime spot for her.

She was wearing neon-lime hot pants, chunky stacked heels with ankle straps, and a not-up-to-the-job black halter top. Her hair was short, straight, and black. She looked luscious . . . but already too used to stay that way for much longer. Perfect.

She played it perfect, too. Let the Corvette cruise by the girls on the corner, then stepped out and waved like she was greeting a friend. I pulled over. She poked her head in the window.

“Any sign of him?” I asked her.

“Nothing.”

“Okay. Get in. If he is out there, let’s give him something to see.”

I brought her back about twenty minutes later. She jumped out quick, still trying to stuff her breasts back into the halter top as I left rubber pulling away.

At the corner, I passed the Camaro, Flacco behind the wheel. Making sure Ann wouldn’t be spending any time out there alone.

And by the time Flacco came back, I was ready with the pickup.

“Anything?” I asked, as soon as she climbed in.

“No. But he’s there.”

“How do you know?”

“I got the high-sign from one of the girls on the corner. He’s been around tonight. Collecting. I figure I’ve been doing so much business he hasn’t had a chance to move on me yet.”

“We’re going to do one more. You remember?”

“Yes,” she said impatiently. “Black Corvette, yellow Camaro, blue pickup—all done. Next up’s a rusty old Pontiac.”

“Good. Now, don’t be—”

“Just relax, B.B. I’m not getting in any strange cars.”

“And if he does make his move . . .”

“I just turn it over, and watch where he goes, if I can. I don’t try and follow him,” she recited, sighing deeply to show she didn’t need another rehearsal.

“Okay.”

“At least it’s easier to do it in a truck.” She chuckled.

“Ann . . .”

“Just stop it, all right? I’m fine. I know what I’m doing. He’s not going to do anything if I turn over the money.”

“And you think Kruger will really pay off? Tell me what he knows?”

“If you get it done? Sure. That’s his rep. He’s had it a long time. And he wants to keep it.”

I pulled over where she told me. Saw several other cars full of the same cargo. But this was no Lovers’ Lane; it was the checkout line in a sex supermarket, and I wasn’t worried about disturbos interrupting the action. Ann made herself comfortable on the front seat, her head in my lap. From the outside, it would look like the real thing.

“Are you going to do it?” she asked, softly.

“What? This isn’t a—”

“Not this,” she said harshly, giving my cock a squeeze. “Help me get the Ultracept.”

“I told you before. I don’t know if—”

“I don’t have much more time.”

“Then maybe you’d better go ahead without me.”

“Didn’t anything I showed you mean anything?”

“You’ve got me confused with one of the good guys,” I told her.

“No, I don’t. How does a hundred thousand dollars—in cash—sound to you?”

“Like nice words.”

“Not just words.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Never mind. Just take me back and let’s get this part done. Then we’ll . . . then you’ll see.”

I met Gordo where we’d arranged. Flacco and I changed places. I took the passenger seat of the ’Vette, he got behind the wheel of the pickup and moved off. Gordo drove me around to the back of the vacant lot, kept the peek while I pulled on a black hooded sweatshirt. I was already wearing black jersey pants, black running shoes, and black socks. A thin pair of black calfskin gloves covered my hands. I pulled a navy watch cap so low down on my head that only my eyes showed . . . then I slashed some light-eating black grease below them, and pulled the hood up. The Beretta went into my waistband, concealed by the sweatshirt. I fitted a heavy rubber wristband over the black leather slapjack, and I was ready.

Gordo looked me over, nodded approval, and vanished. He’d be close by, in case I had to exit fast.

I’d been over the waste ground a couple of times in daylight, and had a sense of where things were. I found a deep pool of pitch-black near a pile of rubble that was an open invitation to rats, and settled in.

From where I knelt, I could see the old Pontiac pull up. Watched Ann climb in. I knew I’d have some time to wait, so I concentrated on my breathing, letting the ground come up inside of me, settling my heartbeat, trying to become one with the rubble I was lurking in.

By the time I’d achieved that state, I knew we weren’t alone.

It took me a few minutes to focus him out of the shadows. Tall and slender, wearing a denim jacket with some kind of glitter design sewn along the sleeves, light-colored slacks that billowed around the knees, then narrowed to the top of shiny boots that looked like plastic alligator, at least from the thirty yards or so that separated us.

He wasn’t so much lurking as lounging, his stance as lame as his outfit. Whoever schooled him forgot to mention that predators don’t pose. There’s always bigger ones around. Or smarter ones.

He stuck something in his mouth and fired it up. From how long it took him to get it going, I figured it for a blunt. Pathetic little punk. Then I thought about the white knife, and let the ice come in.

All he did for the next fifteen minutes was watch the street, drag on his maryjane stogie, and fidget like a guy who thought he was going to get stood up. He was about as inconspicuous as a macaw on a glacier.

The Pontiac rolled to the curb. Ann got out, taking her time, as if she was scanning the street for new customers. When nothing showed, she stepped into the lot, walked behind an abandoned sofa, pulled the hot pants down to her thighs, and squatted below my sight line.

I couldn’t tell if she was relieving herself, or just making it look real. The watcher thought it was real—he hung back until she straightened up and pulled her pants back on. When he made his move, I made mine, cutting across his path, hanging just over his right shoulder so I’d be ready to follow him as soon as he split.

I didn’t want to get close enough to spook him. Couldn’t hear what either of them said, but I could see him brace her. Saw the white knife that earned him his rep. Watched Ann open her tiny little purse and take something out, hand it to him.

I saw him turn to leave. That should have been it, then—just follow him to his crib and take care of business. But he changed the game when he reached out and grabbed Ann by the arm. I saw the white knife slash, heard her make a grunting sound and go down to one knee. I was already moving by then, heard him say, “Fucking cunt! Don’t ever forget me!” as he backhanded her across the face.

Ann saw me coming, waved her hand frantically. He took it as a “No more!” gesture. I took it that she wanted me to stay with the plan. He made up my mind for me when he wheeled and headed back toward where he’d come from.

As I merged with the shadows, I caught a glimpse of Ann sticking a small packet in her teeth, tearing it open with one hand, then smearing it all over her arm. Alcohol swab? I couldn’t wait to see—the knifeman was moving now. Not exactly running, but making good time. And plenty of noise. Following him was no trick.

Ann’s guess about his hideout was on the money. He made his way through an alley to the side of an abandoned building. The door was barely hanging on the hinges. But when he swung it open, I could see a metal gate inside. His key opened the padlock. He stepped inside, about to vanish.

“Show me your hands, punk. Empty!” I said softly, the Beretta a couple of feet from the back of his head.

He whirled to face me. “I . . .”

“Now!” I almost whispered, cocking the piece.

His hands came up. Slow and open.

“You made a mistake,” I said, moving toward him, using the cushion of air between us to force him back inside the building. We were in a long, unlit hallway. All I could make out behind him was a set of stairs.

“Look, man. You got the wrong—”

“I don’t think so. They told me, look for a jailhouse turnout who carries a little white knife. And that’s you, right?”

“I’m not no—”

“Yeah, you are. That’s why you hate women so bad. And the white knife, that’s like your trademark, huh?”

“That was your woman? I didn’t know—”

“My woman? I look like a fucking pimp to you, pussy?”

“No, man. I didn’t mean—”

“Where’s your partner?”

“My . . . I don’t have no—”

“I don’t care what you call him, punk. The nigger you’ve been working with.”

“Look, you don’t get—”

“Yeah. I do,” I said, reading his face. “I do now. He’s not your partner, he’s your jockey, right?”

“Cocksucker!” he snarled, dropping his right shoulder to swing. I chopped the Beretta viciously into the exposed left side of his neck. He slumped against the wall, making a mewling sound, left hand hanging loosely at his side. I brought my knee up in a feint. He went for it, tried to cup his balls with his good hand. By then, the slapjack was in my left hand. I crushed his right cheekbone with it.

I pocketed the slapjack, then turned him over. It was hard to do with only one hand, especially with him vomiting, but I managed it without letting go of the Beretta. When I saw there was nothing left to him, I went back to work with the slapjack, elbows and knees, all the while whispering promises about how much worse this could get, until he passed out.

Kruger hadn’t asked for a body. And he hadn’t offered enough to trade for one, either. My job was done.

I started to get up and fade away when I flashed on Ann. In that vacant lot. The white knife . . .

A good needle-artist could change the tattoos on his hands. But no surgeon was going to reattach the first two joints of both his index fingers. I took them with me.

The maggot wasn’t going to bleed to death, even in that abandoned building—I used the little blowtorch to cauterize the nice clean amputations his pretty white knife had made.

By the time I got back to the vacant lot, Ann was gone.

“She took off in her own ride. The Subaru,” Gordo told me. “I asked her if she wanted to go to the hospital, but she told me she had it under control. I didn’t know what to—”

“You handled it perfect, Gordo. Let’s get out of here.”

“You have to do the motherfucker?”

I unwrapped the black handkerchief, showed Gordo the two index fingers.

“Should have taken his fucking cojones. He cut that girl for no—”

“He didn’t have any to take. Besides, the other one’s still out there.”

“Yeah? You think that gusano could describe you?”

“Not a chance,” I said confidently. “His eyes were closed.” But even as I spoke, I knew he’d gotten a real good look at Ann. And if I was right about the black guy being the jockey . . .

“Where you want to toss the fingers, hombre?” Gordo asked.

“Anyplace there’s rats,” I told him.

“Never in all my life been no place where there ain’t,” he said, pointing the Corvette toward the waterfront.

“You okay?” I said into the cell phone, relieved that she’d answered at all.

“Fine. It was a clean cut. Shallow. He was just like any other trick, doing whatever he has to do to get off.”

“Look, knife wounds can be—”

“It’s fine, okay? I swabbed it out, put on some antibiotic paste, gave myself a tetanus shot, and butterflied it closed. It was strictly subcue, didn’t get near the muscle. I’ll be fine.”

“You did that all yourself? You didn’t go to the—?”

“Don’t be dense,” she said curtly. “And don’t talk so much on the phone.”

“Okay. When do we get to see—?”

“Meet me at my . . . at the place I use.”

“When?”

“Now.”

“Can you drop me at—?”

“No, hombre. Here’s what’s up. I call Flacco, he comes to where we park, we leave you the ’Vette. You come back whenever you come back.”

“Why not just—?”

“Don’t be putting us in a cross, amigo,” he said, his voice full of that special sadness that works best in Spanish. “Gem asks us—and—you know what?—I don’t think she’s gonna ask us, but, if she does—we tell her the truth, understand? We don’t want to know where you meet anybody. Especially that woman.”

“It’s just a—”

“Don’t matter what it is. What you think it is, anyway. We had your back tonight, yes?”

“Yes. And I’m—”

“You don’t got to be nothing, man. Like we told you; it’s for Gem, bottom line. Get it?”

“Yeah. Thanks, Gordo.”

“De nada.”

As I guided the Corvette to where Ann said she’d be, I turned to one of the blues programs you can find on KBOO at odd hours. Slim Harpo’s “What’s Going On?” growled its way out of the speakers. The way I was going, I might make that one my Portland theme song.

The radio kept it going. Butterfield’s “Our Love Is Drifting.” Then Bo Diddley’s “Before You Accuse Me.” As if the DJ knew I was listening.

But before I could call Hong the other mule, what I had to figure out was . . . if it was really my stall.

Ann was waiting on me, her left biceps wrapped in a startlingly white bandage.

“Pretty sexy-looking, huh?” she greeted me.

Considering the bandage was all she was wearing, I decided not to guess what game she was playing and just nodded.

“What happened?” she asked, following me to the armchair.

“I took your signal, shadowed him back to where he was holed up. He went for his knife,” I lied, planting my self-defense seed just in case. “He ended up getting hurt.”

“Bad?”

“Yeah.”

“Dead?”

“No.”

“Think he’ll go to the cops?”

“Not a chance.”

“And he’s done putting the muscle on the girls?”

“He’s done with muscle, period.”

“So we can go to Kruger now.”

“We’d better give it a few days. No reason Kruger should take anyone’s word for anything. Besides,” I said, watching her closely, “that other one—the black guy—he’s still out there.”

“But he never cut—”

“Listen to me, Ann. I was there, okay?”

“So was I.”

“Not the same way I was. And you don’t come from the same place I do. The white guy, he liked doing what he did. But, the way I see it, the black guy, the whole shakedown thing was his idea. And he had a bigger plan in mind than these penny-ante payoffs.”

“What are you saying?”

“That it may not be over. And if it’s not, we’ve got nothing to trade to Kruger.”

“Damn! All this for . . .”

“Maybe not. But for the next few days, I think we have to play it out.”

“How?”

“You go back on the stroll. Or at least be visible. And I’ll be right with you. Only not.”

“Not . . . what?”

“Visible.”

“Like my bodyguard?”

“Not like tonight. If I even see him, I’m going to drop him.”

“But you don’t know what he looks like. And neither do I. Those descriptions, they aren’t worth the . . .”

“If it’s like I think, it won’t matter,” I told her, keeping my voice level.

“I don’t—”

I reached over, grabbed the fleshy pad at the inside of her thigh, squeezed it hard, pulling her closer to me.

“You’re—”

“I know I am,” I said. “But you are going to listen. And you are going to fucking ‘care,’ understand?”

“Yes! Now let me—”

I released my grip.

“You want to kiss it and make it better?” she half-snarled, flexing her thigh.

“You really are a stupid bitch, aren’t you? Fuck you, listen or don’t. The way I see it, the black guy can’t let this one go. He’s got a lot invested. Plus, he has to show his punk he’s stronger, understand?”

“No.”

“Stop pouting and pay attention. The black guy wasn’t the lackey; he was the leader. He’s been watching the street for a while. He probably knows you’re no hooker. He probably knows your car. And he’s probably going to try to take you out.”

“Kill me?”

“At the very least, hurt you. Real, real bad.”

She dropped into my lap. A bruise was blossoming on the inside of her thigh. It took me a minute to realize she was crying.

Gem wasn’t around when I got back to the loft. I realized how I felt about that when I let out the breath I was holding.

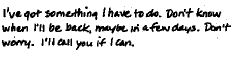

It didn’t take me long to throw everything I needed into my duffel. I found one of her cross-ruled pads; wrote:

I spent a minute trying to think of how to close it. Came up with nothing. So that’s how I signed it, too.

The penthouse topped a high-rise in downtown Portland. The woman who let us in looked to be in her early forties—impossible to tell when they’ve got unlimited money and are willing to spend it on their looks. The living room was overpowered by a condo-sized aquarium, densely packed with brilliantly colored fish. I didn’t recognize anything inside it except for what looked like a pair of miniature gray sharks near the bottom.

“It probably started with gays smuggling AZT,” the woman said. “That wasn’t even for pain, necessarily. But the pain of knowing there’s something out there that could maybe save you—or give you more of your life—and you can’t have it, that’s . . .”

“You’re sure about the Ultracept?” Ann interrupted.

The rich lady didn’t seem to mind. “Absolutely sure. Men just love to boast, don’t they?” she said, talking to Ann while giving me a piece-of-meat look. “It’s not information they’d guard zealously, like some hot stock tip. One thing about those dot-com parties, honey, they’re much more egalitarian than the kind you’d find at a country club. They’re all so very into mind, you know? Nerdy little biochemists who wouldn’t get listened to at a backyard cookout behind one of their tract houses, well, they get a lot of attention from people who just come at the prospect of a new IPO.”

“I’ll need some—”

“Whatever.” The rich lady waved her away. “Is this the man you’re going to use?” she asked.

“No,” Ann said smoothly.

“He doesn’t talk much. Is he yours?”

I didn’t rise to the bait.

“He’s not anybody’s,” Ann told her.

The football game filled the big-screen TV that dominated the glassed-in back porch of the little house set into the side of a hill. I figured it for European pro; it was too early for pre-season NFL.

“Hi, Pop,” Ann greeted the massive man in the recliner. She bent down to give him a kiss on the cheek. “Who’s winning?”

“Not the fans, that’s for damn sure,” the old man snorted.

“Pop used to play,” Ann told me.

“Is that right?”

“That’s right,” he answered. “Played for NYU when it was a national power.” Seeing my slightly raised eyebrows, he went on, “That was before your time, of course. But you could look it up. Hell, I played against Vince Lombardi; that was the caliber of the opposition back then.”

“The game’s changed since—”

“Changed? It’s not the same game, son. We didn’t play with all those pads. And the helmets we had, they wouldn’t turn a good slap. You played both ways then, offense and defense. None of this ‘special teams’ crap, either.”

“And no steroids,” Ann put in.

“That’s right, gal,” he said, smiling approvingly. “Annie knows more about the game than ninety-nine percent of the wannabe faggots who lose the rent money every week.”

“People bet their emotions,” I told him, on more familiar ground now.

“They do; that’s a fact,” the old man said. “Especially with pro ball. Doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. What’s the point betting on men who don’t give a damn themselves?”

“You mean the big salaries?”

“I mean the guaranteed salaries. When I played pro, it was a pretty harsh deal. Fifty bucks if you won. And five if you lost.”

“Was that a lot of—?”

“In 1936? That was still the shadow of the Depression. Fifty bucks, that was more than most men could hope to make in a month, and you could earn it in a couple of hard hours.”

“Who’d you play for?”

“Ah, teams you wouldn’t recognize. Not the big leagues. My dad did that,” he said proudly. “He played for the Canton Bulldogs, before the NFL. With me, it was all semi-pro. I was just a kid then. I did time with the City Island Skippers. . . . You know where City Island is?”

“Sure. In The Bronx.”

“Ah! You from the City?”

“Born and raised.”

“Good! Best place in the world . . . if you’re young and strong.”

“Doesn’t hurt to be rich and white, either.”

“That doesn’t hurt anywhere, son. I played with the Paterson Panthers, too. Same time as I was playing college ball. Way it worked, you played college on Saturdays, pro on Sundays.”

“Did the coaches know about it?”

His laugh was deep and harsh. “Know about it? Who the hell do you think took us to the games on Sunday? And got paid to do it?”

“I thought they were insane-strict with amateurs back then.”

“Yeah, if your name was Jim Thorpe, the racist hypocrites. The same ones who wouldn’t let Marty Glickman run in the Olympics, mark my words. Nah, they all knew. And they all looked the other way.”

“Did you play pro ball after college?”

“Never finished college,” he said, pride and sadness mixed in his voice. “Once that piece of shit Hitler made his move, well, I was bound and determined to make mine.”

“Pop was a war hero,” Ann said, standing next to him, hand on his soldier, as if daring me to dispute it.

“Shut up, gal,” he said, grinning. “I wasn’t a hero, son. Got a few medals, but they gave those out like cigarettes to bar girls, if you were in on any of the big ones. I started at Normandy and made it all the way up with my unit—what was left of it by then. But I’ll tell you this: wasn’t for guys like me, guys your age, you’d be in a slave-labor camp or gassed by now. You’re a Gypsy, right?”

“Right,” I said. No point in telling this fiercely proud old man that I didn’t have a clue as to what I was. And even less pride in it.

He had small eyes, light blue, set deep into a broad face. I watched his eyes watching me. “You were a soldier yourself, weren’t you?” he asked.

“Not me.”

“You’ve got the look. Maybe you were one of those mercenaries . . . ?”

“I was in Africa. During a war. But I wasn’t serving—”

“I don’t hold with that,” he said, plenty of power still in his barrel chest. “When I went in, I could speak a little high-school French. So they put me in charge of a Senegalese gun crew. Bravest fighting men I ever saw in my life. Didn’t have much use for the damn mortars, I’ll tell you that. Couldn’t wait to get nose-to-nose with the krauts. One volley, and they pulled those big damn knives and charged. I don’t hold with a white man killing people who aren’t bothering him. Far as I’m concerned, Custer got what he fucking deserved.”

“Pop . . .” Ann said, putting a hand on his arm.

“Ah, she’s always worried about my blood pressure, aren’t you, gal?”

“I just don’t want you to get all excited over nothing. B.B. wasn’t a mercenary, that’s all he was trying to tell you.”

“B.B.?” he asked me.

“That’s what it says on the birth certificate,” I told him, truthfully.

The old man sat in silence for a minute. Then he turned to Ann and looked a silent question at her, his glance including me in a way I didn’t understand.

“We’re going to do it, Pop,” she told him, her eyes shining.

The old man took a deep breath. “I watched her go,” he said, his once-concrete body shuddering at the memory. “That fucking Fentanyl patch, that was supposed to take all her pain. Well, it didn’t. And my wife, she was the strongest woman—the strongest person—I ever knew. She wasn’t afraid of a thing on this earth. All she ever cared about, right down to the end, was what was going to happen to me after she was gone. She was . . . she was screaming, and they wouldn’t give her any more medication, the slimy little . . . I got my hands on one of them once. Shook him like a goddamned rag doll until his eyeballs clicked. So they gave me a shot. Told me I was lucky they didn’t put me in jail. Watching Sherry like she was, I thought my heart was going to snap right in my chest. And then Annie came. With the right stuff. And when my Sherry went out, she went with a smile on her face. You understand what I’m telling you, son?”

“Yes.”

“I hope you do. I hope you’re not fooled by this damn cane I have to use to get around with now. Whatever my little Annie wants, she’s got, long as I’m alive. And when I’m gone, she gets—”

“Shut up, Pop,” Ann said, punching him on the arm hard enough to make a lesser man wince.

The old man just chuckled. “You sure I can’t come along?”

“No, Pop. But you’re in the plan, I promise.”

“Honey, think about it, all right? I can drive. I can pull a trigger. Maybe not like I could, but good enough. What difference would jail make to me now? Be about the same as here, way I see it. They’d have a TV there, I could watch the games. You’d still come and visit. Food’s food. And ever since my Sherry left, I don’t care nothing about . . .”

“Jail’s not like that,” I told him. “Not anymore.” Gently, so he’d know I wasn’t being disrespectful.

He gave me a long, hard look. Nodded. “I see Sherry every night, before I go to bed,” the old man said softly. “She’s smiling. At peace. I know she’s waiting for me.”

Ann was silent for the first half-hour of the drive back. “You never asked me,” she said, suddenly. “About Pop.”

“What’s to ask?”

“If he’s my real father, or . . .”

“He’s your real father,” I told her. “Biology’s got nothing to do with things like that.”

“You have . . . ?”

“Family, too? Yeah. Back home.”

“You miss them?”

“You going to miss him when he’s gone?”

The mobile home hadn’t been mobile for decades. It lurched on its cracked concrete slab as if held in place by the endless guy-wires running from it to the ground. Maybe it had been painted green, once. Now it was impossible to tell. Driving up the rutted dirt road, obeying the signs that said “5 Miles Per Hour!!!” in self-defense, I had mentally placed the trailer about midway up the prestige scale in that particular park. The whole place looked like an insane breeding farm for kids, dogs, and satellite dishes.

Ann said, “We’re right up the road,” into her cell phone.

When we approached the door, it opened before she could knock.

“About time!” a tall, wasp-waisted woman with shoulder-length, improbably red hair yelled at Ann, grabbing her in a hug hard enough for me to hear the air pop out.

“I told you we’d be here,” Ann said, as soon as she could get her breath.

“This him?” the redhead asked.

“B. B. Hazard, meet SueEllen Hathaway.”

“Hmmm . . .” she said. “What’d you look like before you had your face rearranged?”

“I was so good-looking, women used to give me presents.”

“Is that right?” she said, flashing a grin. Her teeth were way too perfect for a trailer-park diet.

“Yeah. But the clinic always had a cure for it.”

“I’ll just bet,” she said, laughing. Then, over her shoulder to Ann: “And, honey, that’s SueEllen Fennell now.”

“You went back to your maiden name?” Ann asked her.

“Always do, child. Always come back here, too. This address makes it a lot easier for my lawyers to squeeze the max out of my exes.”

“Don’t they make you sign a pre-nup?” I asked her.

The redhead fired a killer smile at me, instantly shifted to a sexy pout, put her hands behind her back, bowed her head, thrust her hips a little forward, said, “Oh, baby, you don’t love me at all, do you? Not one little bit, you don’t! You just like what I . . . do for you. Like I’m some mangy whore, after your money. I mean, who’s in charge, Daddy? All this,” she whispered, cupping my balls like she was testing them for weight, “or those nasty little lawyers? Don’t they work for you, sweetheart?”

I laughed. Couldn’t help myself.

“It’s not funny,” she said, still mock-pouting. She turned and walked off. The back pockets on her jeans danced. I could see where a rich old man wouldn’t have a chance.

Ann plopped down on a sagging bile-yellow couch, patted the spot next to her. I took a seat. The redhead perched on the arm of a chair, crossing her ridiculously long legs. She was wearing white spike heels . . . like putting whipped cream on coconut cake.

We’d been touring around for days, and I thought I had it figured out by then. “Who was it for you?” I asked her.

“My brother,” she said, no hesitation. “My little brother Rex. They named him right. He was a king. My mother wasn’t worth crap, and my father made her look like a goddess. I took care of Rex from the time he was born. Anything he ever needed, anything he ever wanted, I got it for him. I was his big sister, and I could do anything. I did all kinds of things to be able to do that. Never bothered me. Rex was my precious.

“When he got sick, I could see it in his eyes. ‘Big Sister, you got to fix this for me.’ And, Christ knows, I tried. I looked for the Devil to sell him my soul. But he wasn’t around. Or maybe he figured mine wasn’t worth it, I don’t know. Rex was always a delicate little boy. He wasn’t much for standing pain. When it came, he . . . I died a thousand times every time he . . . hurt. His pain was so real to me, I could feel its . . . texture, like a piece of cloth against my skin.

“And the pain, it took everything from him. It . . . degraded him. He had no dignity. They wouldn’t give him what he needed. Kept telling me what the ‘dose’ was supposed to be—like he was a fucking gas tank and they were reading a gauge to know when he was full!

“Well, Big Sister, she knows how to play that. I got him what he needed, right to the end. ‘You always watch out for me, SueEllen,’ that’s what he said, just before he left. And I been snake-mean ever since. It just sucked all the honey out of my heart. Before it . . . happened, I never thought about much. I was a party girl. Just having fun. And taking care of Rex. After he went, I got to thinking. How many other boys there were, dying like that. No dignity. So I looked around until I found Ann.”

“Without all the money you put up, we’d never have been able to—”

“Oh no you don’t, missy,” the redhead snapped at her. “I am in on this. That is what you promised. I want to do it with my own hands this time.”

“I said—”

“I don’t care what you said. If you just came for financing, you came to the wrong place, this time. You want my money, you got to take my body, too. How’s that for a twist?” she laughed, looking at me.

I gave her a neutral half-smile, kept my mouth shut.

The redhead kept her green eyes on me. “Ann thinks she’s been around. And she has. But not around men. Me, I have. Plenty. And I’m not dumb enough to think every ex-con’s a tough guy.”

“I didn’t say I was—”

“Which?”

“Either.”

“Oh, you been in prison, baby. Or someplace bad. What I want to know is, did it make you bad?”

“Some say I was born bad.”

“And SueEllen Fennell says nobody’s born bad. That’s one of those Christian lies. Nothing but a damn fund-raiser. Answer my question.”

“Ask Ann,” I told her. “I’m going for a walk.”

The trailer park wasn’t designed for tourists. I found the DMZ between the whites and the Mexicans—a ditch filled with something liquid. I sat down on the bank, in a spot from where I could keep an eye on SueEllen’s trailer, slitted my eyes against the sun, and breathed shallow. After a while, my mind drifted to where it always goes when I need to figure something out.

When I came around, my watch said it was almost an hour later. And the math I’d been doing kept coming out to the same total, no matter how many times I added it up.

“Some of those ‘gatekeeper’ nurses, they’d be happier working at Dachau,” the emaciated man in the wheelchair told me. “When they see you coming, they look for the pain in your eyes. It gets them excited, the dirty little degenerates.”

“Douglas . . .” Ann said.

“But you know what really gets them off?” he said to me. “When they get to tell you ‘no.’ “

The small house was modest, but in pristine condition, its fresh coat of blue paint with white trim set off against a masterful landscaping job that used boulders for sculpture. The ’Vette’s big tires crunched on the pebbled driveway. In the carport, an ancient pink Firebird squatted next to an immaculate Harley hard-tail chopper, its gleaming chrome fighting iridescent green lacquer for attention.

The man who answered the door was big, powerfully built, with dark, intelligent eyes. He looked past Ann to me. “I told Dawn we were coming,” Ann said.

He nodded, stepped aside.

The living room was dominated by a rose-colored futon couch. And the striking strawberry-blonde who sat on it. She was a pretty woman, but you could see she’d once been gorgeous. And way too young to have aged so much.

Ann went over to her. They exchanged a gentle hug and a kiss. The man who’d opened the door took up a position behind the couch.

“Tell him, Dawn,” Ann said.

The woman’s gaze was clear and direct, azure eyes dancing with anger. But her voice was soft and calm, almost soothing.

“I’ve got MS,” she said. “When I was first diagnosed, I set out to find out everything I could about it. Kind of ‘know your enemy.’ Back then, the medical establishment would go into this ‘Pain is not usually a significant factor in MS’ routine every time patients complained. Now, finally, it looks like they figured it out. . . .”

“Or decided to finally give a fuck!” the man standing behind her said.

Dawn reached back with her right hand as he was reaching down with his. Their hands met as if connected by an invisible wire. “Yes,” she said. “And now the Multiple Sclerosis Society is admitting that as many as seventy percent of folks with MS have what they call ‘clinically significant pain’ at some point, with around forty-eight percent of us suffering from it chronically.”

“You couldn’t get painkillers for MS?” I asked her, surprised despite everything I’d been hearing.

“Well, you could always get drugs,” she sneered. “Even in the bad old days, neurologists liked handing them out—stuff like Xanax and Valium. Not because our muscle cramps and flexor spasms were ‘real,’ you understand. Since the pain was ‘all in our heads,’ they figured the tranqs would calm us down and make the problems in our brains and in our spines magically disappear. And since they did acknowledge that the deep fatigue was ‘real,’ you could always get stimulants.”

“But aren’t all those just as addictive as painkillers?” I asked her.

“Addictive?” She laughed. “Oh, hell yes. I had one neuro prescribing eighty to a hundred milligrams of Valium a day for me. She told me not to worry, there was no chance of becoming addicted. Needless to say, she was full of it. She just wanted her patients calm and placid, so they wouldn’t complain or take up too much of her time. Medicaid wasn’t paying her to give a damn, just to keep us quiet.”

Her left arm twitched. Her mouth was calm, but I saw the stab in her eyes. She took a deep breath through her nose, pushed it into her stomach, then her chest, and finally into her throat. Let it out, slow. A yoga practitioner, then. People in pain try every path out of that jungle.

“Let me tell you,” she went on, “detoxing from the Valium was a megaton worse than jonesing off cocaine. They used to say that was nonaddictive, too. But when I was young, I was into all kinds of street drugs, even freebasing. And I got off all of them myself. No programs, no nothing. But that Valium . . . damn!

“And all the stims they hand out for fatigue, they have pretty serious side effects . . . plus a potential for permanent damage I’m not willing to accept. The hell with the neuros. These days, I treat the fatigue with good strong coffee and naps.”

“What about the pain?”

“All I get for that is the medical marijuana—it’s the only ‘illegal’ drug I’ve used since I got pregnant, and Tam’s eighteen now. And in college,” she said, proudly. “But even that doesn’t always work.”

“And that slimy Supreme Court just struck down the law that allows medical marijuana,” Ann said, fiercely. “They won’t let people even—”

“Shhh, honey,” Dawn said to her. “Look,” she said earnestly, turning to me, leaning forward slightly, her man’s big hand on her shoulder, “the thing about neurologically based chronic pain is, it doesn’t work like ‘normal’ pain. Pot isn’t enough. It relaxes the muscles just great, but does nothing at all for ‘nerve burn.’ It’s like a really bad sunburn, only all over your whole body. I can even feel it inside—like if you could get a sunburn on your large intestine, or something.

“And the thing about that is, when it gets bad enough, it makes you . . . I don’t know . . . something less than human. When you can’t sleep, can’t sit up, can’t move, can’t get any kind of relief, just lay there and cry, curled up in a ball. It got to the point where I was willing to do just about . . . anything to make it stop, even for a few minutes.”

“The only people who really understand pain are the ones who have it,” her man said, making it clear he was ready to help a few doctors learn. “When Dawn scratched her cornea, that lowlife punk in the white coat acted like she did it on purpose, just to score a few stinking Vicodins. You think I couldn’t find better stuff in ten minutes? You think I don’t know where the tweek labs are? If Dawn hadn’t . . .”

He didn’t finish. Didn’t have to.

“What’s with the Grand Tour?” I asked Ann on the drive back toward Portland.

“I’m not sure what you mean.”

“All these people, the ones you’re making sure I meet. They’re all in on whatever scheme you’ve got going. What do I need to see them for?”

“I thought, maybe if you knew that it wasn’t just about cancer . . . if you knew the . . . caliber of the people we’ve got involved, and why they’re doing it, you’d—”

“What? Enlist in the cause? This was supposed to be a trade, remember?”

“I told you, I’m ready to take you back to Kruger any—”

“And I told you, I don’t think it’s over. And if I want to get anything out of him, I need to make sure it is.”

“That’s the real reason you’ve been with me every second, then. Not because you really wanted to meet the others.”

“You like saying things like ‘real reason,’ don’t you? Like you’re just pure virgin goodness and, me, I’m a man for hire. You’re right about the last part, anyway. Only thing is, I’m not a stupid man for hire. Reason you brought me around to all those people is so they’d get a good long look at me, right? Just in case something goes wrong . . .”

“What could go—?”

“I think you’ve got a lot of information, and maybe even some halfass plan, but you’re not sure yet. Besides, I think maybe you’ve got desire confused with skill.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I knew a girl once. Janelle. She was loyal to the core. The kind of girl who’d never drop a dime. But she was so dumb, she might let one slip, you understand?”

“Yes,” she said, keeping her anger at bay because she wanted something. Or maybe she was smart enough to realize I wasn’t talking about her.

“We’ve been doing this running around for almost a week,” I told her. “I met a lot of people. More than one who could do anything I could do. Dawn’s man, he’s a good example. So here’s what I think, lady. I think I’m the perfect man for your job. Because the people you’ve got, they’re all good people. In your mind, anyway. You don’t mind them doing some stealing, maybe. But violence, that’s not their thing, as far as you’re concerned. And that’s all that counts, what you think. No plan is perfect. If things go wrong, if somebody has to be hurt—”

“Like that . . . man with the white knife.”

“Yeah. Like him. I’m perfect for it, the way you got it scoped. If I have to take a fall, well, I’ve been down before. And you know I wouldn’t take anybody else with me.”

“You think I set up the whole—?”

“Yeah. Yeah, I do. I mean, sure, it’s true: there was a freak doing shakedown. And Kruger was burned about it. And maybe there even are a couple of men looking for Rosebud, too. But I think this was all about me proving in. Again.”

“What are you talking about?”

“A test. Another test.”

“That’s not true! I need your help, I told you that. And I wanted to show you that we could . . . I mean, SueEllen alone, she’s good for the money I promised you. But I never thought it would come to—”

“I see how careful you are about risking your own people. You had it your way, none of them would be in on it.”

“They’re not criminals. All they want is to—”

“Sure. I’ve heard it. Heard a lot of it, these past few days. So it’s just you and me, right, bitch? Joan of Arc and the expendable fucking ex-con.”

She did a lousy job of trying to slap me as we were rounding a long curve, but a pretty good job of almost running us off the road. I kept my right hand and forearm in a blocking position in case she wanted to take another shot, but she seemed done.

“You bastard,” she said, quietly.

“I was in a war, once,” I said, softly. “There were two kinds of people you never wanted to go into the bush with: morons and martyrs. Understand?”

“Yes!”

“These drugs you want to hijack—you get caught doing it, they’ll never get into the right hands. So that only leaves three possibilities.”

“What?” she snapped.

“Either you want to get caught, go out in a blaze of glory, get a lot of media attention about your great sacrifice . . . like that. Or you don’t really have a plan; just a lot of information.”

“You said there were three.”

“Yeah. Or you plan to use me as bait: send me down a blind tunnel, tip the cops, then make your own move while I’ve got them tied up for a while.”

“I don’t even know what you’re talking about. How could you tie up a bunch of cops?”

“I don’t mean with ropes. I mean . . . I mean, I’m not going back to prison. So it might take them a long time to bring me in. And it wouldn’t be cheap at their end. And I think you know all that.”

“Maybe you give me too much credit.”

“Maybe. Only I don’t think so. I think people spend so much time looking at your chest they never figure out how smart you are.”

“And you, you’re, like, immune?” she said, bitterly.

“Not immune. I just don’t get D-cup blindness.”

“Good,” she said. “Fuck yourself.”

The light was gone by the time we got back to Portland. Ann had changed in a gas-station restroom, so when she popped out of the Subaru she looked ready for work. I was slouched in the passenger seat, making it look like she was working unleashed, no pimp. We couldn’t be sure what information the knifeman had given his boss. We couldn’t even be sure he’d given any information at all. There hadn’t been anything in the papers, but that didn’t necessarily mean he’d even survived. So we stayed with the script.

Ann took a few tentative steps on the cheap spike heels, wiggling her bottom like she was practicing her moves. She headed for the same patch in the vacant lot where it had all started. I settled in to wait.

When it happened, I almost didn’t pick him up. A black kid, looked maybe nineteen, smooth brown-skin face, neatly trimmed natural. He was wearing a way-oversize black-and-white flannel shirt with sleeves so long they covered his hands, moving in a bouncy, prancing strut, covering ground like he owned it. Typical gangsta-boy moves, about as menacing as Martha Stewart.

But I was working, so I hit the switch and the window slid down in sync with the kid rolling up on Ann’s left side. That’s when I saw the chrome muzzle protruding from the tip of his right sleeve. He was maybe fifteen feet away and closing when he brought the gun up in the trigger-boy’s Hollywood flat-sided grip.

By then, my left forearm was along the windowsill, with the Beretta resting on top. I had three into him before Ann heard the sound of the shots.

“Get in here!” I yelled at her.

She ran toward the car, stumbled to her knees, got up quickly, snatching one of the spike heels off the ground, and half-hopped her way around to the driver’s side. I was already next to the kid’s body, relieved despite myself to see the faint light from down the block reflect on the flashy chrome semi-auto in his hand—it was the real thing, all right.

I knew, from the standard mumbo-jumbo every shooter gets when he can’t afford anything better than Legal Aid, that “self-defense” also includes “defense of others.” But if I shot the kid again once he was down, I couldn’t ever use that one in court. I balanced it in my head for split seconds. The people who’d ambushed me back in New York hadn’t made sure of their kill, and paid heavy for it later. But I couldn’t see a sign he could make it even if someone around there had 911’ed the action. He spasmed once. Then he crossed over.

I was back inside in a flash, and Ann had us gone from the scene in less than that.

Her hands were steady on the wheel as she slid the Subaru around corners, not giving the impression of great speed, but really covering ground. My hands were trembling a little, so I left them in my pockets.

“What happened?” she asked.

“That was the other one.”

“He was going to—?”

“Kill you? Yeah. That’s what the fucking gun was for.”

“B.B., take it easy, okay? I’m all right. He didn’t—”

“This piece—the one I used—it has to go. Quick. We get stopped with it in the car, I’m done.”

“But you were just protecting me!” she said, as if reading my mind back when I stood over the kid’s body.

“That’s a law-school thing. Maybe even a courtroom thing. But with my record, even if I eventually walked, I’d be no-bailed for months, maybe years. And by then, people would know who I am.”

“Who you really are, you mean.”

“That’s right. Now, just go where I tell you.”

“¿Qué pasa?” Gordo asked me, as if walking into the garage at one in the morning was the most normal thing in the world.

“I need to borrow some tools.”

“What for, man? You ain’t no mechanic. Just bring whatever you got in here and we’ll—”

“It’s not a car. And it doesn’t need fixing; it needs destroying. Better you don’t see what it is, okay?”

He gave me a long look. “This . . . thing, it’s, like, metal, right?”

“Sure.”

“Not another . . . ?”

“No.”

“¿Cuánto?”

“Just the one,” I told him.

“I know this guy,” he said. “He’s got his own junkyard. Works a car-crusher there.”

“It has to be now, Gordo.”

“Sí. Just go and get it, compadre. Take me ten, fifteen minutes. Take you hours. I do it perfect. You do it, maybe not so good. Just go and get it.”

The unrecognizable pile of metallic filings and shavings and chips made a gentle rattling sound when Gordo shook the clear plastic box that held them. “Like a maraca, huh?” He laughed.

I pointed to Gordo and Flacco, separately. Bowed slightly. Said, “Obligado.” And walked out of the garage.

Ann was still in the front seat of her Subaru, but now she was dressed casual, in a pale-blue pullover and jeans.

“Where to?” she asked me.

“You’ve got all kinds of medical stuff, right?”

“Sure.”

“Got sulfuric acid?” I asked.

In the shadows of one of the bridges, just before a steel-gray dawn broke, I poured all that was left of the pistol out of a big glass jar into the Columbia River. We’d kept the news on the radio, but either the kid’s body was still in that vacant lot, or he hadn’t been important enough to crack the airwaves.

I went back to the apartment Ann used as a hideout. She said she wanted a shower. I wanted about four of them, but I told her to go first.

The next thing I remembered was waking up. It was late afternoon. I’d never had that shower, but I was stripped, laying across the bed, a soft, warm blanket across my back.

Ann.

I could say I was half asleep. I could say she started it. I could say I was still heavy-blooded with the killing in that vacant lot. And it would all be true.

But not the truth.

She ended up on her back, her face in my neck, not even trying to match her own counterthrusts with mine, just getting there. It didn’t matter who I was, maybe—she never called my name. When I felt her teeth part on my neck, I slipped my shoulder so she lost her grip. She reached out with one hand, grabbed a pillow, stuffed the end of it into her mouth, and bucked under me until she let go.

By the time I finished, she was already going slack. I felt as if I’d lost a sprint.

“Do you want a smoke?” she asked me, later.

“Huh?”

“A cigarette. Some people like to smoke after . . .”

“You read that in a book?”

“Look,” she said, propping herself up on one elbow, “I’m not a hooker, you already figured that out. But I’m not a virgin, either.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Which?”

“Either.”

“Did I do something wrong?”

“No,” I told her. “Not you.”

Later, when I was in the shower, my back to the spray, she parted the curtain and climbed into the tub, facing me. “This is the perfect place,” she said into my ear.

I didn’t say anything.

“I never tried to swallow before. I don’t know if I can. And if I can’t, it’ll all just wash right off. . . .”

When she carefully got down on her knees, I wasn’t half asleep. Turned out she couldn’t swallow it all. And that she was right about it not mattering.

But not the way she meant it.

When I got back to the loft, it was empty. But my note was missing. In its place, a piece of heavy red paper, folded origami-style to make a cradle for a single fortune cookie. Chinese inside Japanese—Gem’s idea of a joke? She once told me how the Vietnamese soldiers finally stopped the Cambodian mass-murderers, who supposedly took their ideology from the Chinese, who still hated the Japanese. . . . I remembered how she laughed bitterly when anyone used terms like “pan-Asian” to her face. I picked up the fortune cookie. It was weightless in my palm. I made a tight fist, crushed it to dust.

A tiny piece of paper was left when I opened my hand. Hand-lettered, in all caps:

It wasn’t like Gem to be cryptic. Mysterious, sure; but not mystical. This read like one of those sayings that took meaning only from interpretation . . . like the Bible. It sounded like a caution. But, for some reason I couldn’t pin down, it felt like a threat.

I stayed around long enough to take another shower, shave, change my clothes. I didn’t know what to do with all the laundry I’d accumulated during the past few days, but somehow I knew, if I handled it myself, that would be the end of everything with Gem.

If it wasn’t already.

Kruger didn’t put us through any elaborate ceremony this time. No sooner had we walked in the club than one of his girls came over and ushered us to his table.

When Ann started to slide into the booth like she had before, Kruger shook his head no. At the same time, he rapped twice on the tabletop with his two-finger ring. All the girls in the booth with him got up as if they’d been jerked by puppeteers.

Kruger rolled his head on his neck, like a fighter getting ready to come out for the first round. But it had nothing to do with getting out the kinks. His eyes swept the place, making sure everyone got the message: we wanted to be alone.

“You do good work,” he said.

“I keep my word,” I answered. Not acknowledging, reminding.

“Names help you, or you just want what they said?”

“Everything for everything.”

“Yes. Only I never asked for ‘everything,’ remember?”

“I don’t remember you asking for anything.”

He eye-measured me for a few seconds. Nodded to himself, as if confirming his own diagnosis. “G-men. Partners. Longtime, from the way they were with each other, you know what I mean?”

“Yeah.”

“Chambliss and Underhill. Salt and pepper.”

“Not new boys?”

“Not close. These guys had a lot of miles on their clocks. Very soft-shoe.”

“And they wanted?”

“What you figured. This girl. The runaway. Rosebud Carpin. They had photos. Good ones, recent.”

“And they thought you had her?”

“No, man. Even the feds know I don’t go near that kind of thing. What they wanted was . . . what you wanted. Keep an eye out; pull their coat if I got a line on her.”

“Just that?”

“Well, they sort of implied they’d be real grateful if I could put some . . . personnel on the matter as well.”

“How’d they come on? Muscle or grease?”

“Wasn’t a single threat between the two of them, man. Just how much they’d, you know, appreciate it if I could be of assistance. Like I told you, all soft-shoe. Nice little shuffle. ‘Even the most astute businessman can find himself in delicate situations occasionally, sir, especially with agencies such as the IRS. I am quite confident you would find it to your advantage to have certain, shall we say, references, should such a situation effectuate.’ “

He had a gift for imitation; I felt like I was listening to the G-men themselves. “You took them seriously, right?”

“As a punctured lung,” he said solemnly. “And I’ve got people looking. Okay, that square us?”

“No,” I said, watching his eyes.

“I’m not following you, Mr. Hazard. I already told you everything they—”

“What would square us,” I said, very soft, “is if you were to call me first. Not a lot first, just a little head start, understand? You get information, you sit on it just long enough to call me, then you go ahead and do what you have to do.”

“But if she’s not there when they go looking, how much of a favor did I really do them, then?”

“They’re pros. They’ll know she was wherever you said she was, just jumped out a little before they closed in, that’s all. They’ll be grateful.” I paused a long few seconds. “I’ll be, too. Everybody wins.”

He took a little sip from a tall glass with some colorless liquid and ice in it. Maybe water. Maybe vodka. Couldn’t tell from any expression on his face.

“A little while ago,” he said, “a young man was brought into the ER. Got in some weird accident. Chopped off the tips of a couple of his fingers. Must have happened when he fell down that flight of steps, busted his face all to pieces. He’s never going to walk without a limp, either.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah. They didn’t buy his story in the ER, especially when they ran a blood tox and found he’d been blasted with some primo horse before he got dropped off. Whoever shot him up knew exactly what they were doing—he was feeling no pain, but he was coherent enough to stay with his story. So the ER called the cops. But this guy, he wasn’t saying anything. Ex-con, you know what they can be like.”

“I’ve heard.”

“What I heard was that his street name was something like . . . Blaze, I think. Looked like someone tried to put out his fire.”

“Or just made it hard for him to strike any matches himself.”

“There’s that,” he acknowledged, saluting me with his glass of whatever. “Anyway, whoever was shaking down the night girls, that all stopped.”

“And that’s good, right?”

“It is. Should be sweet out there now. Only . . .”

“What?”

“Only there was a shooting right on one of the strolls. Pretty unusual. I mean, around here, you can’t buy dope and pussy on the same corner. It’s just not done, you understand? If it wasn’t about dope, had to be gangbangers. The guy who got smoked, he was a black dude, so the cops, I guess they’re satisfied.”

“Why tell me?”

“Just making conversation. This black guy, he looked young, the way I’m told. Only, turns out he was thirty-four. Too old to be banging. And he sure wasn’t an OG. Not local, either—they had to get their info from his prints.”

“Doesn’t sound like he was Joe Citizen, either.”