Twentieth Chapter

The North Quarter of the city looked as if a migration of the population were in progress. The streets were crowded with people, all moving toward the North Gate.

When the palanquin of Judge Dee was carried through the gate, the crowd made way in sullen silence. But as soon as they saw the small, closed sedan chair in which Mrs. Loo was carried along, they burst out in loud cheers.

The long file of people went through the snow hills to the northwest part of the city, toward the plateau where the main graveyard was located. They followed the path winding among the larger and smaller grave mounds, and converged on the open grave in the center, where the constables had erected an open shed of reed mats.

As he descended from his palanquin the judge saw that the temporary tribunal had been set up as well as circumstances permitted. A high wooden table served as bench, and the senior scribe sat at a side table, blowing in his hands to keep them warm. In front of the open grave mound stood a large coffin, supported on trestles. The undertaker and his assistants stood by its side. Thick reed mats had been spread out over the snow in front, and Kuo was squatting there by a portable stove, vigorously fanning the fire.

About three hundred people stood in a wide circle all around. The judge sat down in the only chair behind the bench, and Ma Joong and Chiao Tai stood themselves on either side of him. Tao Gan had walked over to the coffin and was examining it curiously.

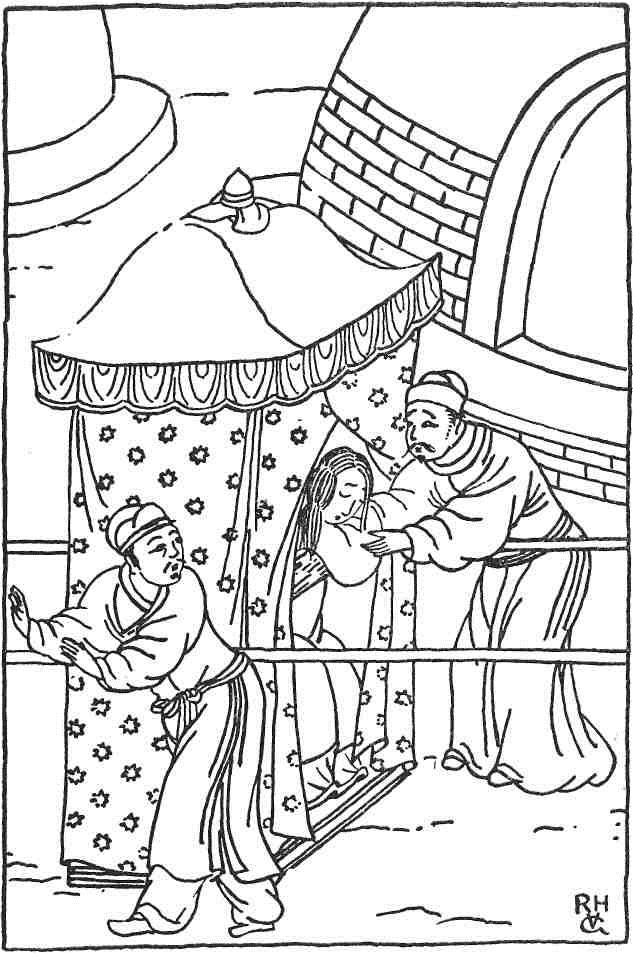

The bearers put down Mrs. Loo's sedan chair and the headman pulled the screen curtain open. He drew back with a gasp. They saw the still body of Mrs. Loo, slumped over the crossbar.

Muttering angrily the crowd drew closer.

"Have a look at that woman!" Judge Dee ordered Kuo. To his assistants he whispered: Heaven forbid that the woman has died on our hands."

Kuo carefully lifted Mrs. Loo's head. Suddenly her eyelids fluttered. She heaved a deep sigh. Kuo removed the crossbar, and assisted her as she staggered to the shed, supporting herself on a cane. When she saw the open grave mound, she shrank back and covered her face with her sleeve.

"Nothing but play-acting," Tao Gan muttered disgustedly.

"Yes," Judge Dee said worriedly, "but the crowd loves it."

He struck the table with his gavel. It sounded curiously weak in the cold, open air.

"We shall now," he announced in a loud voice, "proceed to the autopsy on the corpse of the late Loo Ming."

Suddenly Mrs. Loo looked up. Supporting herself on her stick she said slowly:

Mrs. Loo arrives at the cemetery

"Your Honor is the father and mother of us, the common people. This morning in the tribunal I spoke rashly, because as a poor young widow I had to defend my honor, and that of our Master Lan. But I received the just punishment for my unseemly conduct. Now I beg Your Honor on my knees to let the matter rest here, and not to desecrate the coffin of my poor dead husband."

She sank to her knees and knocked her forehead on the ground three times.

A murmur of approval rose from the onlookers. Here was a reasonable proposal for a compromise, a settlement so familiar to them in their daily lives.

The judge tapped on the bench.

"I, the magistrate," he said firmly, "should never have ordered this autopsy if I didn't have ample proof that Loo Ming was murdered. This woman has a clever tongue, but she shall not prevent me from executing my duties. Open the coffin!"

As the undertaker stepped forward, Mrs. Loo again rose. Half-turning to the crowd she shouted:

"How can you oppress your people like this? Is that your conception of being a magistrate? You maintain that I murdered my husband, but what evidence did you bring forward? Let me tell you that although you are the magistrate here, you are not omnipotent! They say that the doors of the higher authorities are always open for the persecuted and the oppressed. And remember, when a magistrate has been proved to have falsely accused an innocent person, the law shall mete out to the offender the same punishment he wanted to give the falsely accused! I may be a defenseless young widow, but I shall not rest until that judge's cap has been removed from your head!"

Loud shouts of "She's right! We won't have an autopsy!" rose from the crowd.

"Silence!" the judge called out. "If the corpse fails to show clear proof of murder, I shall gladly take the punishment to be meted out to that woman!"

As Mrs. Loo again made to speak, Judge Dee pointed to the coffin and continued quickly: "Since the proof is there, what are we waiting for?" As the crowd seemed to hesitate, he barked at the undertaker: "Proceed!"

The undertaker hammered his chisel under the lid, and his two helpers set to work on the other side of the coffin. Soon they had loosened the heavy lid, and lowered it to the ground. They covered their mouth and nose with their neckcloth, and took the body out of the coffin together with the thick mat on which it had rested inside. They put it down in front of the bench. Some of the onlookers who in their eagerness to miss nothing had come very near, now drew back hastily. The corpse presented a sickening sight.

Kuo placed two vases with burning incense sticks on either side of the dead body. Having covered his face with a veil of thin gauze, he replaced his thick gloves by thin leather ones. He looked up at the judge for the sign to begin.

Judge Dee filled in the official form, then said to the undertaker:

"Before we start the autopsy, I want your statement as to how you opened the grave."

"In accordance with Your Honor's instructions," the undertaker said respectfully, "this person and his two assistants opened the tomb after noon. They found the stone plate that closes the grave in exactly the same condition as when they put it there five months ago."

The judge nodded, and gave the sign to the coroner.

Kuo cleaned the corpse with a towel dipped in hot water, then examined it inch by inch. All watched his progress in tense silence.

When he had completed the front side, he rolled the corpse over and began examining the back of the skull. He probed its base with his forefinger, then went on to examine the back of the corpse. Judge Dee's face grew pale.

At last Kuo rose, and turned to the judge to report.

"Having now completed the examination of the outside of the body," he said, "I report that there are no signs that this man met with a violent death."

The onlookers began to shout, "The magistrate lied! Set the woman free!" But the people in the front row called out to those behind to be quiet, and listen to the end of the report.

"Therefore," Kuo continued, "this person now requests Your Honor's permission to proceed to the inside examination, so as to verify whether poison has been administered."

Before the judge could answer, Mrs. Loo screamed:

"Isn't this enough? Must the poor body be submitted to further indignities?"

"Let that official put the noose around his own neck, Mrs. Loo!" a man in the front row shouted. "We know you are innocent!"

Mrs. Loo wanted to scream something again, but Judge Dee had already given the sign to the coroner, and the onlookers shouted at Mrs. Loo to keep quiet.

Kuo worked on the body for a long time, probing with a lamella of polished silver, and carefully studying the ends of the bones that were sticking out of the decomposed body.

When he rose he gave the judge a puzzled look. It was very still in the packed graveyard now. After some hesitation Kuo said:

"I have to report also that the inside of the body doesn't show any marks that poison was administered. To the best of my knowledge this man died a natural death."

Mrs. Loo screamed something, but her voice was drowned in the angry shouts of the crowd. They surged forward toward the shed, and pushed the constables aside. Those in front shouted:

"Kill that dog official! He has desecrated a grave!"

Judge Dee left his seat and went to stand in front of the bench. Ma Joong and Chiao Tai sprang to his side, but he roughly pushed them away.

When the people in the front row saw the expression on Judge Dee's face, they involuntarily stepped back and fell silent. Those behind them stopped their shouting, to hear what was going on.

Folding his arms in his sleeves the judge called out in a stentorian voice:

"I have said that I would resign, and I shall do so! But not before I have verified one more point. I remind you that as long as I have not yet tendered my resignation, I am still the magistrate here. You can kill me if you like, but remember that you are then rebels, rising against the Imperial Government, and that you will suffer the consequences! Make up your minds; I am here!"

The crowd looked with awe at the impressive figure. They hesitated.

Judge Dee went on quickly:

"If there are any guildmasters here, let them come forward, so that I can entrust to them the reburial of the corpse."

As a burly man, the master of the Butchers' Guild, detached himself from the crowd, the judge ordered:

"You will supervise the undertakers when they place the body in the coffin, and you will see to it that it is replaced in the tomb. Then you will have the entrance sealed."

He turned around and ascended his palanquin.

Late that night a doleful silence reigned in Judge Dee's private office. The judge sat behind his desk, his shaggy eyebrows knit in a deep frown. The glowing coals in the brazier had turned to ashes, and it was bitterly cold in the large room. But neither the judge nor his lieutenants noticed it.

When the large candle on the desk began to splutter, the judge spoke up at last:

"We have now reviewed all possible means for settling this case. And we are agreed that unless we discover new evidence, I am finished. We have to find the evidence, and we have to find it quickly."

Tao Gan lighted a new candle. The flickering light shone on their haggard faces.

A knock sounded on the door. The clerk came in and announced excitedly that Yeh Pin and Yeh Tai asked to speak to the judge.

Greatly astonished Judge Dee ordered him to bring them in.

Yeh Pin entered, supporting Yeh Tai on his arm. The latter's head and hands were heavily bandaged, his face had an unnatural green color, and he could hardly walk.

When with Ma Joong and Chiao Tai's help Yeh Tai had been made to sit down on the couch, Yeh Pin said:

"This afternoon, Your Honor, four peasants from outside the East Gate brought my brother home on a stretcher. They had found him by accident, lying unconscious behind a drift of snow.

He had a fearful wound on the back of his head, and his fingers were damaged by frostbite. But they looked after him well, and this morning he regained consciousness and told them who he was."

"What happened?" Judge Dee asked eagerly.

"The last I remember," Yeh Tai said in a weak voice, "is that two days ago when I was walking home for dinner, I suddenly received a crushing blow on the back of my head."

"It was Chu Ta-yuan who hit you, Yeh Tai," the judge said. "When did he tell you that Yu Kang and Miss Liao had met secretly in his house?"

"He never told me, Your Honor," Yeh Tai answered. "Once I was waiting outside Chu's library, and heard him talk loudly inside. I thought he was having a quarrel with someone, and put my ear to the door. I heard him raving about Yu Kang and Miss Liao making love under his own roof; he used the most obscene language. Then the steward came and knocked. Chu was suddenly silent, and when I was admitted inside, I saw that he was alone, and quite calm."

Turning to his lieutenants Judge Dee said:

"That clears up the last obscure point connected with the murder of Miss Liao." To Yeh Tai he continued: "Having thus accidentally obtained this knowledge, you blackmailed the unfortunate Yu Kang. But August Heaven has already severely punished you for that."

"My fingers are gone!" Yeh Tai cried out despondently.

The judge gave a sign to Yeh Pin. Together with Ma Joong and Chiao Tai they helped Yeh Tai to the door.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ