“How can it have escaped?” Giulio asked. “Are you saying it’s already reached a height where gravity’s negligible?”

His tone of incredulity was appropriate, but he’d missed the point. Nereo said, “At the altitude it had reached on my last observation, gravity is barely diminished—but it was already moving rapidly enough to guarantee that it would never be brought to a halt. Not by the world—though the sun still had hold of it.”

Yalda looked to Amando, and together they managed to slide the tinted pane aside without the pieces falling on them. The bunker’s five occupants climbed to their feet and scrambled up onto the sand, slipping between the ground and the mirror.

Yalda searched the sky, high to the east. There weren’t many Hurtlers today to confuse the view, and she could see a faint gray speck that could only be Eusebio’s house-sized pillar of rock—engines still blazing, still gaining speed. The escape velocity for the sun itself was only three times greater than the world’s. Given the results from earlier yield experiments, if the rocket burned all its fuel without mishap it could actually end up leaving the solar system.

Giulio addressed Eusebio. “You should come to Red Towers and talk about your plans. Nereo’s already given public lectures on rotational physics, so the ideas aren’t completely new to people, but I can run some articles in the Report beforehand to help your audiences prepare.”

Yalda wondered what was in the crops around Red Towers that was missing from Zeugma’s diet.

Eusebio said, “I’d be delighted.”

Yalda thanked Nereo for his participation. “It’s a pleasure,” he said. “I don’t know if your guess about the Hurtlers is right, but I’m glad someone’s thinking about these possibilities.”

“I can’t interest you in a place on the rocket?”

Nereo buzzed with mirth. “I’d rather stay safe on the ground, and wait for your dozen-fold-great-grandchildren to tell me all the marvelous science they’ve discovered.”

Yalda said, “I get that answer a lot.”

She wished she could have spent longer with Nereo, but he and Giulio needed to get back to Red Towers. Amando brought one of the trucks out of the shed and sped off across the desert with their guests.

Eusebio turned to Yalda. “Will you come to Red Towers with me? Tour the show?”

“If I can get leave from the university.” Yalda hesitated. “Do you think you could pay me a small fee for that?”

“Of course.” Eusebio had invited her several times to become an employee, but so far she’d resisted; she’d wanted to retain her independence, in order to be able to speak her mind to him freely.

She added apologetically, “If I’m not teaching I won’t get paid, and it’s not fair on Lidia and Daria to be looking after the children with no help.”

“Hmm.” Eusebio had already made it clear that he disapproved of what the three of them were doing: women—however capable they could be in other spheres—had not been shaped by nature for the raising of children. There were plenty of widowers in Zeugma desperate for heirs, and prepared to treat them like the flesh of their own co.

But he had more important things to think about than the flaws in Yalda’s domestic life. “Beyond spreading the news to the citizenry of Red Towers,” he said, “I’m hoping your colleague Nereo can arrange a meeting for me with his patron.”

“You can’t get an introduction to Paolo yourself?” Yalda was amused. “Whatever happened to the plutocrats’ network?”

“Networks, plural. They’re not all joined together.”

“Why do you want to meet Paolo?”

“Money,” Eusebio replied bluntly. “My father’s set a ceiling on my investment in the rocket. If I’m going to have to build the whole structure myself—mining and transporting all the sunstone, incorporating it into an artificial shell… if I tried to match the scale of Mount Peerless the costs would be greater by a factor of several gross, but even the smallest viable alternative is far beyond what I can afford on my own.”

“Have you thought of bribing all the people who are entitled to vote on the observatory?” Yalda suggested. “Not just with a shiny new telescope—with money they can put in their own pockets?”

Eusebio was insulted. “I’m not a fool; that was my very first plan. But Acilio has the Council scrutinizing the University’s business very closely, and he has so many spies in the University himself that I doubt I could get away with that kind of thing.”

Yalda joked, “I’m always willing to kill Ludovico, for a nominal fee.”

Eusebio regarded her with a neutral expression for an uncomfortably long moment.

“Don’t tempt me,” he said.

As the train approached Red Towers, Yalda was surprised to discover that the city still lived up to its name. She’d read that the local calmstone deposit with the eponymous hue had been mined out long ago, but now she could see with her own eyes that the skyline still bore an unmistakable red tint. Perhaps the original buildings had been lovingly preserved. Either that, or they’d all been recycled as decorative veneer.

Nereo met her at the station—along with all four of his children, who fought with each other for the thrill of carrying her luggage. Seeing how young they were, Yalda guessed that his co must have lived almost as long as her own grandfather. Nereo was still healthy, though—and no doubt he’d made arrangements for the children to be cared for even if some tragedy struck him down.

“Your friend Eusebio’s already at the house,” Nereo said.

“He had some business in Shattered Hill,” Yalda explained. “We’ve come in from opposite directions.”

Nereo lived within his patron’s walled compound. Yalda’s skin crawled as they walked past the sentries with their knife belts, but the children took the sight for granted. “It’s just a tradition,” Nereo told her, noticing her discomfort. “Paolo has no enemies; those weapons have never been used.”

“Don’t the guards get bored, then?”

Nereo said, “There are worse jobs.”

Eusebio was sitting on the floor in the guest room, reading a copy of The Red Towers Report. He greeted Yalda, then added in a tone of disbelief, “This man Giulio actually read and understood every word in the briefings I sent him. He raises some objections and concerns, but… they’re all entirely sensible.”

“Let’s just strap the whole city to a rocket and get it over with,” Yalda suggested. “Let Red Towers flourish in splendid isolation in the void for an age or two, then they can come back and teach the world how to live.”

They only had a couple of bells before the show, so they went to the hall to familiarise themselves with the layout. Yalda hadn’t been able to bring the equipment to produce the projected backdrops they’d used in Zeugma, but Giulio had organized printed sheets bearing the same material, which would be handed to the audience as they entered. That meant keeping the general lighting on during the performance.

“Seeing all those faces is going to make me anxious,” she told Eusebio, standing on the stage at the front of the empty hall.

“Don’t worry, you’re a professional now.” He squeezed her shoulder reassuringly.

The solution only came to her when she finally stepped out in front of the crowd: she delivered exactly the same message as in Zeugma, but she shifted her attention to her rear gaze and focused on the blank wall behind her, allowing herself to imagine that all the people in the hall were staring, not at her, but at the same soothing whiteness.

After Eusebio had done his part—with a few changes from the original version in which he’d boasted of a rocket the size of a mountain—it was time for questions. Everyone they’d spoken to in Red Towers had told them that they’d have to take questions from the floor; it was the custom here, and if they defied it they would not be forgiven. Giulio—whose employers had paid half the cost of renting the hall, in exchange for the right to display the paper’s name prominently throughout the venue—joined Yalda and Eusebio on stage to moderate.

Yalda braced herself for the predictable “Why can’t I walk to yesterday?” jokes, or perhaps even the perennial “Where’s your co?”

The first questioner Giulio selected, an elderly man, called out, “How will you keep the machinery repaired?”

Eusebio said, “There’ll be workshops within the rocket, equipped for every eventuality.”

The man was unimpressed. “And factories? Mines? Forests?”

“There’ll be stocks of minerals,” Eusebio said, “and gardens for raw materials as well as for food.”

“Stocks to last an age? Soil to last an age? All inside one tower? I don’t think so.”

Giulio chose another questioner.

“How will you control the population?” the woman asked.

“At the moment we have more of a shortage of travelers than an excess,” Eusebio replied.

“Double that number a few dozen times,” she suggested, “then tell me where you’ll put them, and how you’ll feed them.”

Eusebio was beginning to look flustered. Yalda said, “There’ll be the same mortality rates on the rocket as we experience anywhere else. No city’s population actually doubles in a generation.”

“So there’ll be no progress in medicine, then? For era after era, the only thing these travelers will care about is dealing with the Hurtlers… which no longer even threaten them?”

Yalda said, “Progress in medicine could end up controlling population growth as much as it lowers mortality.”

“Could—but what if it doesn’t?”

The questions continued in this fashion: tough but undeniably pertinent. It felt like an eternity before Giulio called a halt; Yalda was so exhausted that it took her a moment to realize that the audience was now cheering enthusiastically.

“That went well,” Giulio whispered to her.

“Really?”

“They took you seriously,” he said. “What more did you want?”

In the foyer, they recruited more than three dozen ground crew volunteers, but no passengers. People here were far more willing than their cousins in Zeugma to accept Yalda’s premise about the Hurtlers, and even the abstract principle behind Eusebio’s solution—but no one was confident that he could build the kind of habitation in which they’d want their own grandchildren to spend their entire lives.

The servant ushered Yalda, Nereo and Eusebio into the dining room, then withdrew.

Paolo was standing at the far end of the room, flipping through a thick stack of papers. He looked younger than Yalda had expected, perhaps a bit more than two dozen years old. He put the papers down on a shelf and approached, gesturing at a wide circle of cushions on the floor. “Welcome to my home! Sit, please!”

Nereo introduced Yalda and Eusebio. Yalda tried not to be intimidated by the opulence of the room; the walls were decorated with an abstract mosaic, and there was a bewildering array of food spread out in front of them, almost none of it familiar to her. To her eye, there was enough to feed at least a dozen people—and when six young men entered the room, the quantity began to seem almost reasonable—but it turned out that Paolo’s sons were just passing through to greet his guests, and would not be joining them.

Six sons! Had he adopted some of them, or taken two co-steads? Either way, if it was a family tradition the house would be overflowing with grandchildren.

The formalities over, Paolo sat with them and urged them to start eating. Yalda made a conscious decision not to hesitate—not to stare at the dishes and try to guess their origins. She was confident that nothing here would be too repellent, let alone dangerous, so it didn’t really matter that she had no idea what she was putting in her mouth. The first few flavors were strange, but not unpleasant. She decided to adopt a fixed expression of mild enjoyment and maintain it throughout the meal, regardless.

Paolo addressed Eusebio. “I’ve heard about your rockets; an extraordinary venture.”

“It’s only just beginning,” Eusebio replied. “To send people safely into the void will take many more years of work.”

“I admire the audacity of your vision,” Paolo said, “and I appreciate that the Hurtlers might well become dangerous. But what exactly do you think your travelers will bring back from a trip into empty space?”

“That’s difficult to predict,” Eusebio admitted. “Imagine, though, how wondrous our cities would appear to a visitor from the eleventh age. They had no engines, no trucks, no trains. Only the crudest lenses. No reliable clocks.”

“But what comes next?” Paolo wondered. “An engine that runs a little more smoothly? A clock that loses no time in a year? Undoubtedly civilized refinements, but how would they safeguard us against the Hurtlers?”

Eusebio said, “Have you heard of the Eternal Flame?”

Yalda was glad she’d already committed to a policy of benign inexpressiveness.

Paolo buzzed amiably—not mocking his guest, but treating this invocation as if it could only have been meant as deliberate, flippant hyperbole.

Eusebio’s tone remained scrupulously polite, but Yalda could see him struggling to keep his frustration in check. “The old stories of the Eternal Flame were misguided in their details,” he said, “but modern ideas suggest that such a process might actually be possible.” He turned to Nereo. “Am I wrong about that?”

Nereo said cautiously, “Rotational physics doesn’t rule it out immediately, the way our earlier understanding of energy did.”

Paolo was surprised. “Honestly?” He put down the loaf he’d been chewing. “So all those wild-eyed alchemists might simply have given up too soon? Ha!” He shot Nereo a reproving glance, as if his science adviser might have thought to mention such an interesting fact a few years earlier.

Eusebio said, “Sir, may I tell you one message we received very clearly from the people of Red Towers last night?”

“Certainly,” Paolo replied.

“My venture, as it stands, is too modest,” Eusebio confessed. “Nobody believes that a few dozen people in a vehicle perhaps the size of this compound could survive long enough to reap the benefits of their situation. The basic physics of the trajectory puts no limit on the length of their journey—no limit on the advantage they could have over us in years. But the practicalities of their situation will be the determining factor. A robust society requires a certain scale, in both people and resources. An isolated camp in the desert with well-chosen supplies might endure for a generation or two, but it takes a whole city to flourish for an age.”

Paolo said, “I understand.” He was silent for a while. “But how large a rocket would be large enough? No one knows. It’s a very big risk to take, based on nothing but guesswork.”

“If it stops the Hurtlers from destroying us,” Eusebio replied, “how could it not be worth it?”

“But that judgment depends not only on the travelers succeeding,” Paolo reasoned, “but also on an absence of other solutions. The same resources spent here on the ground might solve the problem more efficiently. I can’t speak for others, but I do like having my own money doing its work somewhere nearby, where I can watch over it.”

“Yes, sir.” Eusebio lowered his gaze. The rejection could not have been clearer.

Paolo turned to Nereo. “So, perhaps the Eternal Flame could be made real?”

“Perhaps,” Nereo conceded reluctantly. “But there are a number of subtleties to be considered, some of which we barely understand.”

“What if I hired a gross of chemists to go out into the desert and start testing every possible combination of ingredients? Somewhere far from any people they could harm?” Nereo didn’t reply immediately, but Paolo was already warming to his own vision. “We could require that each experiment take place at a location on the map that encoded the particular choice of reagents. That way, it would be apparent from the positions of the craters which reactions should never be attempted again.”

“Ingenious, sir,” Nereo declared. He was being sarcastic, but Paolo chose to take him at his word.

“The credit,” Paolo replied, “should go to our guest, who delivered this inspiration to me.” He bowed his head toward Eusebio.

Throughout their second, final show in Red Towers, Eusebio kept up an admirably professional veneer of optimism, but as soon as they were back in Nereo’s guest room he slumped against the wall.

“It’s too much,” he said numbly. “I can’t do this anymore.”

“We can find someone else to take over the recruitment drive,” Yalda suggested.

“I’m not talking about the recruitment drive! The whole project is impossible. I should give up this idiocy and go back to the railways; let someone else worry about the Hurtlers. I’ll probably be dead before the worst of it, anyway. Why should I care?”

Yalda walked over to him and touched his shoulder reassuringly. “So Paolo won’t invest in the rocket. He’s not the only wealthy person on the planet.”

“But Red Towers is as good as it gets,” Eusebio said. “Journalists here understand the whole message. People listen to our plan and offer intelligent, constructive criticism. But no one here will volunteer to be a passenger, and the man who owns half the city would rather try to resurrect alchemy as his weapon against the Hurtlers than watch his money disappear into the void.”

“It’s a setback,” Yalda admitted. “But don’t make any decisions right now. Things might look different after a few days.”

Eusebio was unconvinced, but he tried to receive her advice graciously. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I couldn’t throw this all away in an instant if I wanted to. It’s not as if someone’s going to walk up to me tomorrow and offer to buy the mining licenses.”

Yalda woke in the night, unsure for a moment where she was. She raised herself up on her elbows to look around the room. Soft-edged shadows tinged with spectral colors stretched across the floor from beneath the window, framing Eusebio’s sleeping form.

He was beautiful, she realized: tall and strong, perfectly shaped even in slumber. How had she never seen that before?

But it was the thought of him that had woken her. If they brought their bodies together now, she was sure she could extract the promise from him. Her flesh wouldn’t die; she’d let her mind and its anxieties fade away, leaving her children with a devoted protector. He was the closest thing to a co she could hope for, and she did not believe he would refuse her. Not here, alone with her; not if she insisted.

She rose to her feet and stood watching him, imagining his skin pressed against her own, rehearsing the words that would convince him. If Paolo could have six sons, why should Eusebio limit himself to two? She would not say a word against his co; she wasn’t asking him to betray his lifelong partner, only to enlarge his prospective family.

Eusebio opened his eyes. She saw him register her presence, her gaze. She expected to be questioned, but he remained silent, as if everything between them was clear to him already. If she lay beside him now, it would not take much persuasion. They both wanted the comfort of this, and the promise of life for their children.

But as she took a step toward him, Yalda felt a chilling clarity spread across her mind. She wanted comfort—not oblivion. And whatever Eusebio wanted, it was not the encumbrance of her children. Nothing in this beguiling vision had any connection to their real plans, their real needs, their real wishes. The oldest part of her believed it could survive this way—as her mother had survived in her—but even that blind hope was misplaced. Eons of persistence would count for nothing when the sky lit up with orthogonal stars.

She said, “The Hurtlers woke me. I’m sorry I disturbed you.”

Eusebio said, “That’s all right, Yalda. Just try to sleep.” He closed his eyes.

Yalda returned to her bed, but she was still awake at dawn.

After breakfast, Amando came in his truck to take Eusebio to another test launch. Eusebio didn’t demur; the sheer momentum of the project still counted for something. At least until the money ran out.

Nereo walked Yalda to the station. “I’m sorry we didn’t have a chance to talk optics,” he said. “I’ve been tinkering with your light equation recently, trying to find the right way of adding a source.”

“Really?” Yalda was intrigued. The equation she’d come up with five years before described the passage of light through empty space, but said nothing about its creation. “How far did you get?”

“I took some inspiration from gravity,” Nereo said. “Think about the potential energy of a massive body, such as a planet. Outside the body, the potential obeys a three-dimensional equation very similar to the one for light: the sum of the second rates of change along the three directions of space is zero. Inside the body, instead of zero that sum is proportional to the density of matter.”

“So you think I should add a similar term to the light equation, to represent the light source?” Yalda thought about this. “But a light wave involves a vector with four components; the source would have to be the same kind of thing.”

Nereo said, “What about a vector that’s aligned with the history of the light source—pointing into its future—with the length of the vector proportional to the density of the source?”

“That’s the right kind of vector,” Yalda conceded, “but what would this ‘density’ actually be describing?” He didn’t mean mass; this was something else entirely.

“Whatever property matter needs in order to produce light,” Nereo replied. “We don’t have a word for it yet; maybe ‘source strength’? But assuming we can put a number on it, we can talk about how tightly it’s packed: the ‘source density’.”

“Hmm.” Yalda worked through the implications as they entered the station. “So if we’re looking at the simplest case, where everything is motionless, only the time component of the equation would be non-zero, and it would have solutions a bit like gravitational potentials.”

“But not quite the same,” Nereo stressed. “These solutions oscillate as you move across space.”

Yalda’s train was boarding; they didn’t have time to take the discussion further. Nereo said, “I’ll send you a copy of my paper when I’ve written it.”

On the journey back to Zeugma, Yalda managed to find one solution to Nereo’s equation herself: the equivalent of the potential energy around a motionless, point-like mass.

For gravity, it had been known since the work of Vittorio an era and a half ago that the potential was inversely proportional to the distance from the mass. For light, the overall strength of the wave diminished with distance in exactly the same fashion, but it also underwent an oscillation with the smallest possible wavelength—that of a wave traveling at infinite speed. All of this was just an idealization—the need to wrap around the cosmos smoothly would impose additional constraints and complications—but it was a start.

Yalda pondered the curve. Perhaps there was something like this present in everything from sunstone to a flower’s petals. Light at the minimum wavelength would be invisible, so when the source was motionless the petals would be dark. But a system of oscillating sources, suitably arranged, might well be able to twist the original pattern into a set of tilted wavefronts, corresponding to light slow enough to lie in the visible realm.

Exact solutions when the source was in motion wouldn’t be easy to find, but the general idea made sense; to generate a wave that moved energy around, something had to feed in the energy in the first place, whether that meant jiggling the end of a string or vibrating your tympanum in air. That the creation of light would draw true energy out of an oscillating source—increasing its kinetic energy, rather than draining it—was a peculiar twist, but that was rotational physics for you.

There was, Yalda realized, another strange twist, arising from Nereo’s choice of a vector aligned with the particle’s history as the term to add to the equation. If you accelerated a light source long enough to curve its history around a half-circle and send it backward in time… then once it was settled on its new, straight trajectory it would be surrounded by a wave that was the opposite of the original. Compared with its earlier self, the pattern of light the source generated would now appear upside-down.

But how could a featureless speck of matter tell which way it was traveling through time? The arrow of time was meant to come solely from entropy’s rise; a lone particle couldn’t grow disordered. A wave changing sign wasn’t as dramatic as the difference between a stone being smashed and the shards spontaneously reassembling, but it did imply that there might be two distinguishable kinds of source, at least when they weren’t moving too rapidly: one “positive”, one “negative”.

It was evening when the train pulled into Zeugma. Yalda didn’t have the energy to face the four squabbling brats at bedtime, so she wandered around the city center for a while, killing time until she was sure they’d be asleep.

When she finally braved the apartment, she was surprised to find Lidia sitting in the front room, in the dark.

“I thought you’d be at work,” Yalda said. “Did they change your shift—or was there some problem with the helper?” The whole point of asking Eusebio to pay her had been to hire someone to watch the children in her place.

“The helper was fine,” Lidia said, “but we didn’t need her tonight.”

“So you’re working mornings again?”

“No, I’ve lost my job.”

“Oh.” Yalda sat beside her. “What happened?”

“Did I tell you about my new supervisor?”

“The idiot who kept asking you to become his deserted brother’s co-stead?” Yalda didn’t believe the rumor that Lidia had murdered her own co, but there were times when it might have been helpful if more people had taken it seriously.

Lidia said, “Two days ago he came up with a new offer: either I hand the children over to his brother, or he tells the factory owner that I’ve been stealing dye.”

“But you only ever took from the spoiled batches. I thought everyone did that!”

“They do,” Lidia replied. “But he told the owner I was taking good jars as well. He had some kind of paperwork prepared, inventory records that made it look plausible. So the owner believed him.”

“What a piece of shit.” Yalda put an arm across her shoulders. “Don’t worry, you’ll find a better job.”

“I’m just tired,” Lidia said, shivering. “I used to think everything would be different by now—by the time I was this old. But what’s changed? There aren’t even women on the Council.”

“No.”

“Why doesn’t your friend Eusebio do something about that?” Lidia demanded.

“Don’t blame him,” Yalda pleaded. “He’s already fighting the Council on a dozen different fronts.”

Lidia was unimpressed. “The whole point of being a new member of the Council is to fight the old guard and get something useful done. But sharing power never seems to be a priority with anyone.”

“Shocking, isn’t it?”

“Will he have free holin on his rocket?” Lidia wondered. “I might join up for that alone.”

Yalda said, “Of course there’ll be free holin. In fact, it looks as if the entire crew will consist of solos and runaways: one of each, in a rocket the size of this room.”

“That’s beginning to sound less tempting.”

Yalda rose. “I’m sorry about your job. I’ll ask around, see if anyone knows of a position…”

“Yeah, thanks.” Lidia put her head in her arms.

As Yalda crossed the room, a slab of sharp-edged brightness on the floor beside the window caught her eye. The diffuse light from the Hurtlers didn’t look like this; it was as if one of their neighbors had stolen a spotlight from the Variety Hall and mounted it on their balcony.

She walked over to the window and looked out. The neighbors weren’t to blame; the light was coming from high above the adjacent tower. A single bluish point was fixed in the sky, displaying no discernible color trail.

Lidia had noticed the light too; she joined Yalda by the window.

“What is it?”

Yalda suddenly realized that she’d seen the same object high in the east when she’d walked out of the railway station—but it had been a great deal paler then, so she hadn’t given it a second thought. “Gemma,” she said. “Or Gemmo.” The naked eye couldn’t separate them, so there was no point guessing which of the two had suffered the change.

Lidia hummed with exasperation; she was in no mood to be mocked. “I might not be an astronomer,” she said, “but I’m not a fool. I know what the planets look like, and none of them are that bright.”

“This one is, now.” A dark, lifeless world that had once shone by nothing but reflected sunlight was turning into a star before their eyes.

Lidia steadied herself against the window frame; she’d grasped Yalda’s meaning. “A Hurtler struck it? And this is the result?”

“It looks that way.” Yalda was surprised at how calm she felt. Tullia had always believed that a large enough Hurtler could set the world on fire. Dark world, living world, star; they were all made of the same kinds of rock, the distinction was just a matter of luck and history.

Lidia said, “Now tell me the good news.”

Good news? Gemma and Gemmo were far away, and much smaller than the sun, so at least the world wouldn’t suffer intolerable heating from the new star.

In fact, the two planets were so far from the sun that the density of the solar wind in their vicinity was believed to be a tiny fraction of its value around the nearer worlds—and no Hurtlers had ever been seen at such a distance, in accord with the idea that it was friction with that gas that made the pebbles burn up. But the lack of the usual pyrotechnics hadn’t prevented this unheralded impact.

The Hurtlers were everywhere, visible or not—and Ludovico’s absurd explanation for them that blamed the solar wind alone was now completely untenable. Yalda didn’t expect him to recant, but the people who’d voted with him against Eusebio’s offer didn’t have the same degree of pride invested in the matter.

Perhaps the new star was no more exotic than the Hurtlers themselves, but its meaning was far easier to read: the only thing that had spared their own planet so far was luck. Any day, any night, the world could go the same way.

“The good news,” Yalda said, “is that we might just get our flying mountain after all.”

12

“Stay close to me!” Yalda called out to the group as they approached a bend in the tunnel. “Anyone suffering from nausea? Weakness? Dizziness?”

A chorus of weary denials came back at her; they were tired of being asked. She’d been pacing the tour carefully—and the mountain’s interior was maintained at higher pressure than the air outside—but everyone’s metabolism was different, and Yalda had decided that it was better to nag than face a crisis. She certainly didn’t want any of these potential recruits associating the place with sickness.

“All right, we’re now coming to one of the top engine feeds.” For the last few saunters the tunnel had been lit solely by the red moss clinging to its walls, but the illumination from a more variegated garden could already be seen spilling around the bend.

As they took the turn, a vast, vaulted chamber appeared in front of them, a disk almost half a stroll wide and a couple of stretches high. It had been hollowed out of the rock three years before, using jackhammers powered by compressed air; no engines or lamps were employed in the presence of naked sunstone. The usual drab moss and some hardy yellow-blossomed vines covered the arched ceiling, but between the supports the floor was a maze of flower beds luminescing in every hue. Many of the plants were arranged haphazardly, or in small, localized designs, but long strands of cerulean and jade could be seen weaving from garden to garden around the gaping black mouths of the boreholes.

“It wasn’t always so colorful here,” Yalda recalled, “but the construction workers brought in different plants over the years.”

“Will you keep the gardens when the engine’s in use?” Nino asked.

“No—that would interfere with the machinery, and in the long term their roots could even damage the cladding. But these plants won’t be destroyed; they’ll be shifted to the permanent gardens higher up.”

Yalda led her dozen charges to the edge of the nearest borehole and invited them to peer down into the gloom. Far below the chamber, the darkness was relieved by four splotches of green and yellow light; clinging to rope ladders that ran the full height of the shaft, workers wreathed in vines were inspecting the hardstone cladding that lined the surrounding sunstone.

“When the engine is operating,” Yalda explained, “these holes will have been filled-in again, but liberator will be pouring down around the edges. If there are gaps in the cladding, the fuel could start burning in the wrong place.”

“This is the top layer of the rocket, isn’t it?” Doroteo asked.

“Yes.”

“So it won’t be in use for a very long time,” he pointed out.

“That’s true, and I’m sure it will be inspected again before it’s fired,” Yalda said. “But that’s no reason for us to neglect the job now.” Her ideal would have been to prepare every piece of machinery in the Peerless in such a way that the travelers would be able to turn around and come home safely whenever they wished—without requiring any new construction work, let alone any radical innovations. But given the current yield from the sunstone, this top layer of fuel would actually be burned away sometime during the decelerate-and-reverse phase, halfway through the journey. Relying on the status quo would not be an option.

Yalda led the group to a stairwell at the rim of the chamber, and they gazed up into its moss-lit heights. Four taut rope ladders ran down the center—installed early in the construction phase and retained in anticipation of weightlessness—but for now a more convenient mode of ascent involved the helical groove three strides deep that had been carved into the wall, its bottom surface tiered to form a spiral staircase.

“We’ll be climbing up four saunters here,” Yalda warned the group, “so please, take it carefully, and rest whenever you need to.”

Fatima said, “I don’t feel weak, but I’m getting hungry.”

“We’ll have lunch soon,” Yalda promised. Fatima was a solo, barely nine years old; Yalda felt anxious every time she looked at the girl. What kind of father would have let her travel alone across the wilderness, to enlist in a one-way trip into the void? But perhaps she’d lied to him in order to come here; perhaps he thought she was hunting for a co-stead in Zeugma.

The group was evenly split between couples and singles; the singles were all women, except for Nino. Yalda hadn’t interrogated Nino about his background, but she’d formed a hunch that he was that rare and shameful thing, a male runaway.

They began trudging slowly up the stairs; the pitch appeared to have been set to discourage running, should anyone have felt tempted. Their footsteps, and the whispered jokes of Assunta and Assunto up ahead, came back at them in multiple echoes from the underside of the stairs above. Beyond their own presence, Yalda could hear an assortment of odd percussive sounds, creaks and murmurs drifting down from higher levels. The workforce inside the mountain had fallen far below its peak, but it still numbered about a dozen gross, and most of the activity now was in the habitation high above the engines.

“Will the travelers be able to see the stars?” Fatima asked Yalda, trailing her by a couple of steps.

“Of course!” Yalda assured her, trying to dispel any notion that the Peerless would end up feeling like a flying dungeon. “There are observation chambers, with clearstone windows—and it will even be possible to go outside for short periods.”

“To stand in the void?” Fatima sounded skeptical, as if this were as fanciful as walking on the sun.

Yalda said, “I’ve been in a hypobaric chamber, as close to zero pressure as the pumps could produce. It feels a bit… tingly, but it’s not painful, and it’s not harmful if you don’t do it for too long.”

“Hmm.” Fatima was begrudgingly impressed. “And in the sky—will they be our stars, or the other stars?”

“That depends on the stage of the journey. Sometimes both will be visible. But I’ll talk about that with everyone later.” A moss-lit staircase wasn’t the place to start displaying four-space diagrams.

They emerged from the stairwell into a wide horizontal tunnel; this one ran all the way around the mountain, but the nearest junction was just a short walk ahead. Yalda offered no warning as to what lay around the corner; the light gave some clues, but the thing itself always took the uninitiated by surprise.

The chamber was no wider than the one below, but it was six times taller—and the broad stone columns supporting the arched ceiling were all but lost among the trees. High above their heads, but far below the treetops, giant violet flowers draped across a network of vines formed a fragmented canopy that divided the forest vertically. With no sunlight to guide their activity, these flowers had organized themselves into two populations with staggered diurnal rhythms, one group opening while the others were closed. Through the gaps left by the sagging, dormant blossoms, shafts of muted violet reflected back by the stone above revealed swirling dust and swooping insect throngs. Even the air moved differently here, driven by complex temperature gradients arising within the vegetation.

Yalda strode forward through the bushes that had been planted around the chamber’s edge, where the ceiling was too low for trees. “This might look like a strange indulgence,” she admitted. “When we have farms, plantations and medicinal gardens, what need is there for wilderness? But if our survival depends on the handful of plants we’ve learned to harvest routinely, this place still encodes more knowledge about light and chemistry than all the books ever written. Every living organism has solved problems concerning the stability of matter and the manipulation of energy that we’re only just beginning to grasp. So I believe it’s prudent to bring as many different kinds of plant and animal life with us as we can.”

“What kind of animals?” Leonia asked; she didn’t sound too happy about the prospect of sharing the Peerless with a teeming menagerie.

“In here right now, there are insects, lizards, voles and shrews. Soon we’ll be adding a few arborines.” Yalda watched the group’s reaction with her rear gaze; eventually it was Ernesto who said, “Aren’t arborines dangerous?”

“Only when threatened,” Yalda declared confidently. “Most of the stories about them are exaggerated. In any case, they’re our closest cousins; if there are medical treatments we need to test, there’s only so much you can learn from a vole.” It was Daria who’d sold her on most of these assertions—the same Daria who’d made half her wealth from impresarios’ claims about the creature’s ferocity.

Fatima said, “What happens when there’s no gravity? Won’t everything… come loose?”

Yalda squatted down and cleared a small patch of soil, exposing the layer of netting that sat over it. “This is attached to the rock with spurs at regular intervals. The root systems bind the soil together, too—and the soil itself is actually quite sticky. A handful of soil will trickle through your fingers easily enough, but an absence of gravity is not the same as turning everything upside down. What I’m expecting is that the air here and in the farms will grow hazy with dust, but there’ll be an equilibrium where that dust is re-adhering to the bulk of the soil as often as it’s breaking free.”

They took the stairs up to one of the farms, and ate a lunch prepared from the local crops. Wheat adapted well to sunlessness; it grew faster in here than on the farms outside, now that Gemma had all but banished night again. The disruption caused by the second sun varied with the season and the year—and there were periods when it rose and set close to the original, almost restoring normality—but the last Yalda had heard from Lucio was that he and her cousins had given up trying to adjust to the complicated cycle and were simply building canopies over all their fields.

Then it was on to the storerooms, workshops and factories, the school, the meeting hall, the apartments. They ended the day in an observation chamber close to the peak, where they watched the sun setting over the plain below, revealing the mountain’s stark shadow in the rival light from the east.

There was a food hall beside the chamber. Yalda found a free patch of floor among the crowd of construction workers and sat everyone down. Up here they were far enough from the sunstone to use lamps; it might have been any busy establishment in Zeugma or Red Towers.

Yalda dropped her recruiting spiel and let the group eat, with no accompaniment but the sputter of firestone and the chatter of their fellow diners. By now they’d seen not the whole of the Peerless, but at least one example of everything it contained. They’d reached the point of being able to imagine what it would be like to spend their lives inside this mountain.

Leonia, who’d been tense throughout the tour, now appeared almost tranquil; Yalda’s guess was that she’d made up her mind to find an easier way of avoiding her co than fleeing into the void in the company of wild animals. Nino looked haunted, but equally resolved to make the opposite choice. Looking back, Yalda realized that every question he’d asked her had concerned something innocuous or trivial; it was as if he’d wanted to appear engaged as a matter of courtesy, but he’d been so committed to his plan from the start that he’d preferred not to delve into anything that might risk swaying him.

With the others, she was unsure. It was as easy to undersell the problems the travelers would face as to oversell them. Anyone who reached the end of the tour believing that the project was hopelessly ill-conceived would walk away—but equally, anyone who was convinced that the triumphant return of the Peerless was inevitable would have scant motivation to join the crew. Rather than sentencing your descendants to indefinite exile, why not choose the version of events that lasted a mere four years, in which your death far from home was replaced by the imminent arrival of the most powerful allies you could hope for? Of course a Hurtler might incinerate the world before then, but it had been five years since Gemma’s ignition, so it wasn’t hard to imagine the same luck holding out for another five.

In between those two extremes was a sweet spot, where the mission’s potential was beyond doubt but its success remained far from guaranteed—allowing a wavering recruit to imagine their own contribution tipping the balance. Yalda aimed squarely for that result, and she no longer felt guilty or manipulative for doing so. The truth was, though she and Eusebio had filled all the jobs that they knew beyond doubt to be essential, there was nothing gratuitous about raising the numbers still higher—increasing the range of skills, temperaments and backgrounds among the travelers. It was like bringing the forest as well as the farms: the Peerless was sure to find a use for everyone, even if they could not yet say what it would be.

“One came back!” Benedetta shouted ecstatically, running across the sandy ground between the main office and the truck compound. There was a rolled-up sheet of paper in her hand. “Yalda! One came back!”

Yalda gestured to the group to wait for her. She’d been about to take them over to the test site to watch a demonstration launch, but if she understood Benedetta’s cryptic exclamation then this was worth a delay.

Yalda jogged over to meet her. “One of the probes returned?”

“Yes!”

“You’re serious?”

“Of course I’m serious! This is the image it took!”

Benedetta unrolled the crumpled sheet.

Yalda had barely taken in the spatter of black specks when Benedetta turned the paper over to show her the opposite side. It had been marked with three signatures in red dye: Benedetta’s, Amando’s and Yalda’s, along with a serial number, an arrow in one corner to fix its orientation in the imaging device… and instructions to anyone finding it upon its return.

Apart from the image on the sensitized side, Yalda certainly recognized the sheet. It was one of a gross that she’d signed at Benedetta’s request, two and a half years earlier, to guarantee their authenticity.

“Who sent this to you?”

“A man in a little village near Mount Respite,” Benedetta said. “I’ll need your authorization to pay him the reward.”

“Do you know what state the probe itself is in?”

“In his letter he said there wasn’t much left of it apart from a few cogs hanging off the frame, but it was still so heavy that he couldn’t afford to send it to us.”

“Add something to the reward to cover the freight, and get us the whole thing.” Yalda took the sheet from her. “Octofurcate me sideways,” she muttered. “You and Amando really did it.” She looked up. “Have you told him yet?”

“He’s in Zeugma helping Eusebio with something.”

“I never thought this would work,” Yalda admitted.

Benedetta chirped gleefully. “I know! That makes it so much better!”

Yalda was still having trouble believing it. She was holding in her hands a sheet of paper that had left the world behind, crossed the void faster than anything but a Hurtler, turned around and come back… and then traveled here by post from Mount Respite.

“Which stage was it taken in?” she asked.

Benedetta pointed to the serial number.

“Meaning…?” Yalda had forgotten what the numbers signified.

“Odd numbers were for the first stage of the journey, when the probe was traveling away from us.”

“Good,” Yalda managed numbly. She thought for a while. “I think you should come and tell my recruits what you’ve found.”

“Of course.”

Yalda introduced Benedetta to the group, then recounted some of the background to the problem. Years before, she had managed to identify a slight asymmetry in the Hurtlers’ light trails, demonstrating that their histories were not precisely orthogonal to the world’s. This had finally made it possible to say which direction they were coming from; until then, their trails might have marked a burning pebble crossing the sky in either direction. But it had revealed nothing about the Hurtlers’ own arrow of time.

Doroteo was confused. “Why doesn’t their arrow of time just point from their origin to their destination?”

Yalda said, “Suppose you drive toward a railway crossing, and you notice that the track doesn’t make a perfect right angle with the road you’re on; it comes in from the left as you approach the crossing. You might think of the ‘origin’ of the track as being a station that lies behind you, to the left—but assuming that this track is only used in one direction, you still have no reason to believe that the trains will actually be traveling from your left to your right.”

Doroteo grappled with the analogy. “So… we can map the geometry of a Hurtler’s history through four-space as a featureless line, but we can’t put an arrow on it. We can’t assume that the tilt you discovered means the Hurtler’s arrow is pointing slightly toward our future; it might as easily be pointing slightly toward our past.”

“Exactly,” Yalda said. “Or at least, that was how things stood until now.”

Benedetta was shy before the strangers, but with Yalda’s encouragement she took over the story.

The probes had been launched two and a half years earlier: six dozen rockets fuelled by sunstone from the mountain’s excavations, fitted with identical instruments and sent out like a swarm of migrating gnats in the hope that one of them would complete its task and find its way home. Their flight plan had been a less ambitious variation on that of the Peerless, reaching just four-fifths the speed of blue light before decelerating and reversing, with literally just a couple of bells spent in free fall along the way. Compressed air, clockwork and cams controlled the timing of the engines, with opposing pairs of thrusters built into the design to avoid the need to rotate the craft. The aim of the project had been to get an imaging device moving as rapidly as possible, parallel to the Hurtlers’ path, first in one direction and then the opposite.

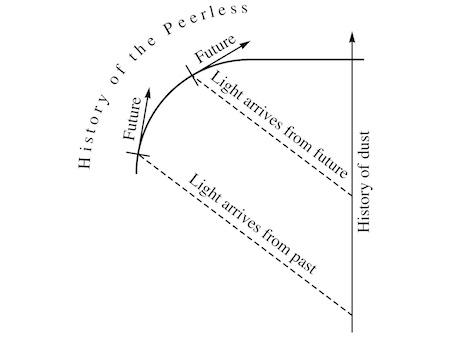

“This paper was made sensitive to ultraviolet light, about one and a half times as fast as blue light,” Benedetta explained, holding up the travel-worn sheet. “The orthogonal stars all lie in our future, so we can’t expect to see them, or image them under ordinary conditions. But the whole meaning of ‘past’ and ‘future’ depends on your state of motion.”

She sketched the relevant histories on her chest.

“With the probe traveling at four-fifths the speed of blue light, infrared light from the orthogonal stars would have reached it at an angle in four-space corresponding to ultraviolet light from the past.” Benedetta held up the evidence again. “So we’ve managed to record an image of these stars—which to us still lie entirely in the future—by giving the probe a velocity that placed part of their history in its past.”

Fatima said, “How do you know those are images of orthogonal stars, not ordinary ones?”

Benedetta gestured at her chest. “Look at the angle between the light and the histories of the ordinary stars. To them, the light’s traveling backward in time! Only the orthogonal stars could have emitted it.”

Yalda added, “And if the orthogonal stars’ future had pointed the other way, then the probe could only have imaged them once it had reversed and was coming back toward us. So we know the direction of the arrow now—not from the Hurtlers themselves, but from the light of these stars whose origin the Hurtlers share.” This finally put to rest Benedetta’s old fear: that the Peerless might be headed straight toward the orthogonal cluster’s past, requiring the rocket to function while opposing the entropic arrow of its surroundings. Now it was clear that it would not face that challenge until the return leg of the journey.

“And how far away are they?” Fatima asked. “These orthogonal stars?”

Benedetta looked down at the images. “We can’t be sure, because we don’t know how bright they are. But if they’re about as luminous as our own stars, the nearest could be no more than a dozen years away.”

The group absorbed this revelation in silence. Five Hurtlers were spreading lazily across the morning sky, and while Gemma itself was below the horizon, here was a promise of interlopers vastly larger than the baubles that had set that world on fire.

Just when Yalda was beginning to think that the stark new threat might push some of the waverers into making a commitment, Leonia broke the mood. “Six dozen probes went up,” she said, “and this is the only one that’s been recovered? What happened? Did all the others end up as craters in the ground?”

“That’s possible,” Benedetta conceded. “Landings are difficult to automate. But the real problem was returning the probes to this tiny speck of rock from such a distance. The world is a very small target; the tolerances required for attitude and thrust control were close to the limits of what any of us believed was feasible. We were lucky to get even one back.”

“But the Peerless will be traveling much farther,” Serafina noted anxiously.

“With people inside it to navigate,” Yalda replied. “It won’t be down to clockwork to get them home.”

Leonia was unswayed. “Be that as it may, when you rehearsed your great project—on a much smaller scale—you only had one success in six dozen. And you were hoping to impress us by juggling voles!”

The demonstration launch Yalda had arranged would carry six of the animals above the atmosphere, then bring them back down again—hopefully still alive. While clearly no surrogate for the flight of the Peerless, this was not a trivial achievement—and some people did find it reassuring to see that Eusebio’s rockets no longer exploded on launch, or cooked their passengers with the engine’s heat.

“What would persuade you, then?” Yalda demanded irritably. “A full-scale rehearsal, where we send up Mount Magnificent with a crew of arborines?”

Leonia responded to this sarcastically grandiose proposal with a much more modest alternative. “It might mean something if you went up yourself, instead of the voles.”

Before Yalda could reply, Benedetta said, “I’ll do it.”

Fatima emitted an anxious hum. “Are you serious?”

Benedetta turned to her. “Absolutely! Just give me a few days to check the rocket and re-arrange things for the new weight.”

Yalda said, “We need to discuss this—”

“That would be a lot more convincing than voles!” Assunto enthused. His co agreed. “What can an animal the size of my hand tell us about the risks of flight?” she complained. “Our bodies are completely different.”

Yalda looked on helplessly as the group debated Benedetta’s offer; the majority soon reached the view that nothing less would be of interest to them. Only Fatima was reluctant to witness such a risky stunt, while Nino struggled to summon up the appearance of caring one way or the other.

Yalda wasn’t going to argue this out with Benedetta in front of everyone; she sent the recruits off to kill some time at the Basetown markets.

Benedetta was already contrite. “That was poorly judged,” she admitted. “I shouldn’t have sprung it on you out of nowhere.”

Yalda said, “Forget about the timing.” Being made to look foolish in front of the recruits was the least of it. “Why do you think you need to do this at all?”

“We’ve talked about it for years,” Benedetta replied. “You, Eusebio, Amando… everyone agrees it would be a good idea to send someone up—but always later. How long is it until the Peerless is launched now?”

“Less than a year, I hope.”

“And we still haven’t put a single person on a rocket!”

“Flesh is flesh,” Yalda said firmly. “What are voles made of—stone? When it comes to the Peerless, the things we have to worry about will be attitude control and cooling—and we’ve got both of them down to a fine art: in the last four dozen test launches, they’ve worked flawlessly. It’s only the landings that have failed.”

“And only three times,” Benedetta pointed out. “So those aren’t bad odds that I’d be facing.”

Yalda said, “No… but if you did this, what would it actually tell us? Whether you survived or not, how would it make the Peerless safer?”

Benedetta had no ready reply for that. “I can’t point to any one thing,” she said finally. “But it still feels wrong to me to try to launch a whole town’s worth of people into the void, without at least one of us going there first. Even if it’s only a gesture, it’s a gesture that will calm some people’s fears, win us a few more recruits and quieten some of our enemies.”

Yalda searched her face. “Why now, though? You see an image of the future—proof that it’s fixed—and suddenly you’re offering to surrender your life to fate?”

Benedetta buzzed, amused by the implication. She held up the paper from the probe. “If I stare at this long enough, do you think I might spot myself living happily among the orthogonal stars?”

Yalda said, “What if I tell you that I’ve seen the future, and it’s voles all the way?”

Benedetta gestured toward the markets. “Then I can confidently predict that most of those recruits will be gone in a couple of days.”

Silvio stood in the doorway of Yalda’s office. “You need to see this new camp,” he said. “Way out of town.”

She looked down at the calculations Benedetta had submitted on the modified test launch. She’d checked them over and over again, but she still hadn’t made a final decision on whether or not to approve the flight.

“Are you sure there’s a problem?” she asked him. Traders sometimes arrived and set up camp in inconvenient places, but it usually only took them a few days to realize that they were better off in Basetown.

Silvio didn’t reply; he’d given his advice, he wasn’t going to repeat it. It was Eusebio who paid his wages, and if Eusebio put Yalda in charge of the project in his absence then that won her a certain amount of courtesy—but not much.

She said, “All right, I’m coming.”

Silvio drove her a few strolls north along the dirt track that ran from Basetown to one of the disused entrances to the mountain. Yalda didn’t know exactly what he’d been doing there himself; maybe Eusebio had him patrolling the whole area.

There were five trucks at the abandoned construction camp, most of them loaded with soil and farming supplies. A couple of dozen people were visible, digging in the dusty ground. In some respects it wasn’t a bad place to farm, Yalda realized; the shadow of the mountain might well block Gemma’s light enough of the time to allow the crops to retain their usual rhythm, without the need for unwieldy awnings. Having to truck in soil wasn’t promising, but once a crop became established the roots of the plants, and the worms that lived among them, could start breaking down the underlying rock.

Yalda climbed down from the cab and approached the farmers.

“Hello,” she called out cheerfully. “Can anyone spare a lapse or two to talk?”

She caught a few people looking away, embarrassed at the realization that they were being addressed by a solo, but one man put down his shovel and walked over to her.

“I’m Vittorio,” he said. “Welcome.”

“I’m Yalda.” She resisted the urge to make a joke about his famous namesake; either he’d be sick of people doing it, or he’d have no idea what she was talking about. “I work with Eusebio from Zeugma—the man who owns the mines here.” That had become the standard euphemism for the rocket project; everyone knew precisely what was going on inside the mountain, and why, but some people who took a dim view of Eusebio’s whole endeavor were less hostile if they weren’t confronted with explicit reminders of it.

“I don’t believe he owns this land,” Vittorio replied defensively.

“No, he doesn’t.” Yalda tried to keep her tone as friendly as possible. “But if you were hoping to trade with his workers, we have a whole town just south of here where you’d be welcome to set up.” If they signed an agreement with some very reasonable conditions, they could farm just as much land as they were using here, sell their produce in the markets and have access to Basetown’s facilities for no cost at all.

“We chose this location with care,” Vittorio assured her.

“Really? It’s a long way from everything but Basetown, and not as close to there as it could be.”

Vittorio made a gesture of indifference. Other members of his community were watching them discreetly, but Yalda didn’t sense any physical threat, just a mood of resentment at her interference.

“I need to be honest with you,” she said. “In less than a year, this land won’t be suitable for farming anymore.” She was trying to work from the most innocent assumptions she could think of: that the chaos in the sky had driven them off their land in search of some reliable diurnal darkness, and they were unaware of quite how soon it would be before Mount Peerless ceased casting its convenient shadow.

“Are you threatening us?” Vittorio sounded genuinely affronted.

She said, “Not at all, but I think you know what I’m talking about. That you won’t have shade for your crops will be the least of it.”

“Ah, so your master Eusebio will consign us all to flames?” Vittorio made no effort now to hide his contempt. “He’d knowingly slaughter this entire community?”

“Let’s not get melodramatic,” Yalda pleaded. “You’ve barely begun to dig your fields, and now you’ve been informed of the danger so you won’t waste your time putting down roots here. Nobody is going to be consigned to flames.”

“So you pay no heed to the fate of Gemma?”

Yalda was confused. “Gemma is why half the planet has given its blessing to Eusebio’s efforts.”

“Gemma,” Vittorio countered, “taught those of us with eyes that an entire world can be lost to flames. But your master has learned nothing, and in his ignorance he’d blindly set this one alight as well.”

Yalda was growing irritated with the whole “master” thing, but it made a change from being told he was her co-stead. She glanced back toward the truck; Silvio was pretending to be taking a nap.

“You think the rocket would set the world on fire?” If that was his honest belief, Yalda could only admire him for deciding to become a living shield against the threatened conflagration, but he might have dropped by the office and asked a few questions first. “It was a Hurtler that ignited Gemma, and it would take a Hurtler to do the same to us,” she declared.

“A Hurtler, and nothing else?” Vittorio buzzed, amused by her rhetoric. “How can you possibly know that?”

Yalda said, “I don’t know that nothing else could do it—but I know what this rocket will and won’t do. Under the mountain, beneath the sunstone, there’s a seam of calmstone; I’ve been there, I’ve touched it with my own hands. We’ve tested the combination, burning one on top of the other, for far, far longer than they’ll stay together at the launch. The calmstone is ablated by the flame, but there’s no sustained reaction that spreads beyond the site. And before you start protesting that the calmstone is unlikely to be pure, we’ve tested dozens of other rocks as well.”

“And how large was your flame?” Vittorio enquired. “The size of a mountain?”

“No, but that’s not the issue,” Yalda explained. “By holding the flame in place longer in the tests, we can achieve identical conditions in a slab a few strides wide.”

Vittorio simply didn’t accept this. “You’ve played around with some childish fireworks, and you think that proves something. The proof is in the sky.”

“If you’re so impressed by the example of Gemma, how do you propose fending off the Hurtlers that would re-enact the whole thing here?” Yalda demanded. “Thwarting Eusebio won’t spare you from that.”

Vittorio was unfazed. “Do you think there were people on Gemma?”

“No.” This was becoming surreal. “What difference does that make?”

“People can douse small fires,” Vittorio replied. “If one kind of stone is burning, the sand of another kind can be fetched to put it out. If there had been people on Gemma, that’s what they would have done, and that world would not have been lost to the flames.”

Yalda didn’t know how to answer this. To hope that quick thinking and a bucketful of sand could defeat the Hurtlers was absurd… but if you scaled it up to something systematic with teams of rostered observers in every village and whole truckloads of inert minerals at the ready, that might actually contain the effects of a small impact.

“How large is a Hurtler?” Vittorio asked her. He held up two fingers, about a scant apart. “This big? Larger? Smaller?”

“About that size,” Yalda conceded.

“So my choice is between a fire that starts from a pebble, and one that starts from this.” Vittorio turned and gestured at the mountain. “Only a fool would choose the greater risk.”

From the top of the rocket, Yalda could see the wind lifting brown dust from the plain to trace out its eddies and flows. “You can still change your mind,” she said.

“But I’ve already completed the trip,” Benedetta replied placidly. “Time is a circle. It’s happened, it’s over; there’s nothing left to choose.”

Yalda hoped that this fatalist blather was just Benedetta teasing her, but there was no point arguing about it now. The last three of the recruits she’d brought up to ogle the tiny cabin were on the ladder heading back to the ground. Benedetta was strapped onto a bench that had been installed in place of the rack of voles’ cages in the original design; the same cool gases would blow over her body as those that had kept the animals safe from hyperthermia in previous launches. The elaborate clockwork around her that would control the timing of the engines and the parachute’s release had been inspected thrice: by Frido, by Yalda, then finally by Benedetta herself. The voles had only merited two inspections.

“I won’t say good luck then; you won’t need it,” Yalda told her.

“Exactly.”

Yalda couldn’t leave it at that; she squatted down beside the bench. “You know, if you’re made famous by this your co might come looking for you.”

“Whose co?” Benedetta retorted. “Nobody here knows my birth name.”

“No, but how many people as crazy as you could have been born in Jade City?”

Benedetta was amused. “You think I’m from Jade City?”

“Aren’t you?” Yalda had always believed that part of her story. “Your accent sounds authentic.”

“You should hear the other six regions I can do.”

Yalda squeezed her shoulder. “See you soon.” She straightened up then climbed out of the cabin; perched on the ledge above the ladder, she slid the hatch firmly into place. Through the window, she saw Benedetta gesture toward the enabling lever, then make a four-fingered hand: on the fourth chime from the clock beside the bench, she’d launch the rocket. This was the normal protocol, but unlike the voles she’d have to initiate the process herself.

Yalda usually had no trouble with heights, but as she descended the ladder she felt a kind of sympathetic vertigo at the thought of the altitude the cabin would soon reach.

On the ground, she pulled the ladder away and let it fall to one side. The recruits were quiet now; even Leonia was subdued as they started back toward the bunker.

When a gust of wind rose up and sprayed stinging dust into their faces, Fatima said, “Someone should make a truck that runs on compressed air.”

“They should,” Yalda agreed. It had probably been discussed at some point, but then slipped off the agenda; that had happened with a lot of good ideas. Compounding the problem of the project’s sheer complexity, some of Eusebio’s fellow investors had insisted that their funds could only be spent directly on the rocket itself, lest they be viewed as mere secondary players when the descendants of the travelers returned. Yalda found it hilarious that anyone believed that such choices could guarantee them access to the project’s ultimate harvest. If the Peerless really did come back after an age in the void—with the kind of technology that could defeat the Hurtlers and everything that threatened to follow them—they’d trade with whomever they liked, on whatever terms they wished. A certain amount of compassion for their distant cousins was the most she was hoping for; any prospect of scrupulous adherence to contracts signed by their long-dead ancestors was just a fantasy Eusebio had encouraged so the plutocrats could part with vast sums of money without having to confront the horrifying reality that it was actually being spent for the common good.

Frido was waiting by the bunker. “How was she?” he asked anxiously.

“Calm,” Yalda said. “She was joking with me.”

Frido stared back across the plain. Yalda decided that they were the ones who were getting the real taste of cosmic determinism; Benedetta could still decide either to launch the rocket or back out, but nothing her two friends did now could influence her choice.

Everyone clambered down into the bunker. It had been years now since a rocket had exploded at launch, but these precautions weren’t arduous, and though the dust was even thicker down here it was good to get out of the wind.

Yalda lay between Frido and Fatima, watching the mirrored horizon. The rocket was almost lost in the brown haze. She glanced over at the clock; there were three lapses still to go.

Leonia said, “What if she loses her resolve, then regains it? If we come out of the bunker and that thing goes off—”

“That’s not going to happen,” Yalda replied. “She’ll launch at the agreed time, or not at all.”

“What if something jams inside the engine feed?” Ernesta asked. “How can you walk away from that safely, if it might unjam at any time and fire the engines?”

Yalda said, “There’s a backup system to close off the liberator tanks. And if that doesn’t work, Benedetta knows how to take the whole engine feed apart.” Can’t you all be quiet, and just let this happen? She closed her eyes; her head was throbbing.

Time passed in silence. Fatima touched her arm warily. Yalda opened her eyes and looked at the clock. Frido counted softly, “Three. Two. One.”

The radiance of burning sunstone burst through the haze and lit up the plain. Benedetta hadn’t flinched; she hadn’t waited one flicker past the chime. As the rocket rose smoothly into the sky the walls of the bunker shook, but it was no more than a gentle nudge. Yalda felt a rush of empathetic delight. This courageous woman had pushed the lever, and the rocket had done her bidding. Cool breezes would be flowing over her skin, her weight would be no more than half above normal, and with her tympanum held rigid the noise of the engine wouldn’t trouble her too much. Yalda, braced the same way, barely registered the sound of the launch as it reached her.

When the rocket went off the edge of the mirror, Yalda scrambled out of the bunker and stood watching it ascend. Frido followed her, and though she gave no instructions to the recruits everyone soon joined them.

In less than a chime Benedetta would be four slogs above the ground—almost nine times the height of Mount Peerless. From her bench, she would be peering through the window and watching the horizon growing ever wider. Yalda’s skin tingled vicariously at the thought of this foretaste of the greater journey: to ascend and return, without the bitterness of parting from the world forever.

Frido had a theodolite on a tripod set up beside the bunker, but Yalda was content to use her naked eyes, merely checking the time on the clock that sat behind them both. Distance soon dimmed the rocket to a faint white speck, but it was not so pale that there was any ambiguity when the engines shut off and it vanished entirely. Now Benedetta would be weightless, as if she’d stepped into the skin of one of her descendants from the generations who would know nothing else.

The rocket would rise another two slogs before gravity brought it to a halt. As five lapses passed, Yalda pictured it slowing, approaching its peak. Would Benedetta have any way of knowing that she’d reached the midpoint of her journey, apart from the reading on her own clock? How well could you judge your speed, when the landscape that offered the only cues was at such a great remove? Yalda tried to imagine the view from this pinnacle, but the task defeated her. She would have to wait to hear it in the traveler’s own words.

For five more lapses the rocket would fall freely, then the engines would start up again, burning more fiercely than during the ascent, slowing the vehicle sufficiently for the parachute to take over and ease its fall. Yalda kept her rear eyes on the clock and her forward gaze raised to the zenith, trying not to be distracted by the Hurtlers.

Where was the speck of light? She glanced at Frido, but he hadn’t spotted it either. She forced herself to remain calm; the wind was whipping up dust all around them, and it was always easier to track the rockets to burn-out than to catch sight of them as they lit up again.

There! Lower and westwards from where she’d been looking, faint but unmistakable. The cross-winds would have given the rocket an unpredictable horizontal push, keeping it from retracing its trajectory precisely—and Yalda suspected that she’d lost her bearings a little, telling herself that she’d kept her gaze fixed when she’d really been following some slowly drifting streak of color in her peripheral vision.

Frido spoke quietly, his words for her alone. “Something’s wrong,” he said. “It’s coming down too fast.”

Yalda couldn’t agree. He had watched more launches then she had, but he was more anxious too; his perceptions were skewed.

The flame grew closer, its intensity becoming painful; in her mind’s eye Yalda followed it down to a point just a few strolls from the launch site. Benedetta would meet them halfway across the plain, waving and shouting triumphantly.

She waited for the flame to cut out, watching the clock as the moment approached. But when it had passed, the engines were still blazing.

“Something’s wrong,” Frido repeated softly. “The burn must have started late.”

As he spoke, the flame went out. Yalda fixed the clock’s reading in her mind: six pauses after the scheduled time. If the entire burn had been delayed for six pauses, the rocket would have been moving more than ten dozen strides per pause faster than intended when the engines cut out and the parachute was unfurled. Falling faster, from a lower altitude.

“What can you see?” Yalda asked him. The recruits were starting to notice their whispering, but Yalda ignored them and watched Frido searching the sky with the theodolite’s small telescope. The unlit rocket itself would be impossible to make out from this distance, but if the parachute was open the white fabric would catch the sun.

Yalda saw it first—her view was wider, and no telescope was needed. Not a flutter of sunlight on cloth, but the full glare of burning sunstone again. She touched Frido’s shoulder; he looked up and cursed in amazement.

“What’s she doing?” he asked numbly.

“Taking control,” Yalda said. The engines had no provision for manual operation, but Benedetta must have dragged the useless timing mechanism out of the way and re-opened the liberator feed herself.

Fatima approached. “I don’t understand,” she complained.

Yalda addressed the recruits, explaining what she believed was happening. The timer must have jammed for a few pauses while the rocket was in free fall, delaying everything that followed. The parachute must have been torn away when it unfurled at too high a speed. The only way to slow the rocket’s descent now was with the engines. Benedetta would try to execute a series of burns that would bring her to the ground safely.

She said no more; all they could do now was watch and hope. But even with perfect knowledge and perfect control, a powered landing could only be a compromise. You needed to be as low as possible before you finally cut the engines, to spare yourself from the fall—but the lower you descended, the more the ground below you would trap heat from the rocket’s exhaust.

And Benedetta did not have perfect knowledge, just a sense of her own weight to gauge the engine’s thrust and an oblique view of the landscape from which to judge her height and velocity. As Yalda watched, the burn intended to slow the rocket’s fall went on too long; the piercing light hung high above the plain for a moment then rose back into the sky.

The flame went out, leaving the rocket invisible again. Yalda tried to think her way back into the cabin, to regain the sense of empathy she’d felt at the moment of launch. Benedetta had already shown quick thinking and resolve, but what she needed most was information.

The engines burst into life once more, showing the rocket far lower than before. Yalda watched it approaching the horizon, afraid it was not slowing quickly enough, but as it entered the dust haze, sending rippling shafts of light and shade across the plain, her spirits soared. It was easier now to judge its trajectory, and it looked as near to perfect as she could have wished. If Benedetta cut the engines at the lowest point, the fall might be survivable.

The flame dimmed slightly, but it did not go out. Yalda peered into the dust and glare, struggling to discern any sign of motion. Frido reached over and touched her arm; he was looking through the theodolite. “She’s trying to get lower,” he said. “She knows she’s close, but she doesn’t think it’s good enough.”

“Is it good enough?”

Frido said, “I think so.”

Then cut the engines, Yalda begged her. Cut the engines and fall.

The light grew brighter, but it remained in place. Yalda was confused, but then she understood: Benedetta hadn’t increased the thrust, but the rocket was now so low that it was heating the ground below it to the point of incandescence.

Frido let out a hum of dismay. “Go up!” he pleaded. “You’ve lost your chance; give it time to cool.”

The glow flared and diffused. The wind shifted, clearing the haze, and Yalda could see exactly what was happening. The ground was ablaze, while the rocket crept toward it, feeding the flames.

Yalda called out “Down!” and managed to push Fatima toward the bunker before the light became blinding and she stumbled. She lay where she’d fallen, her face in the dirt, covering her rear eyes with one arm.

The ground shuddered, but it was not a big explosion; most of the sunstone and liberator had already been used up. She waited for debris, but whatever there was fell short. When she relaxed her tympanum, all she heard was the wind.

Yalda rose to her feet and looked around. Frido was crouched beside her, his head in his hands. Nino was standing, apparently unharmed; the other recruits were still picking themselves up. Fatima peered out from the bunker, humming softly in distress.

In the distance, a patch of blue-white flame jittered over the ground. Yalda couldn’t tell if it was spilt fuel burning or the dust and rock of the plain itself. She watched in silence until the fire had died away.

“When Benedetta wanted to launch her imaging probes,” Eusebio recalled, “she just wore me down. Six dozen was what she wanted; six dozen was what she got. And if I’d been here for the test flight, it would have been the same. Whatever my misgivings, she would have talked me around them.”

Yalda said, “I wish we’d had a way of contacting her family. Or at least a friend somewhere. There must have been someone she would have wanted to be told.”

Eusebio made a gesture of helplessness. “She was a runaway. Whatever farewells she was able to say would have been said long ago.”

Yalda felt a surge of anger at that, though she wasn’t even sure why. Was he exploiting people, by helping them escape their cos? There was no crime in offering a way out, so long as you were honest about what it entailed.

The hut was lit by a single lamp on the floor. Eusebio looked around the bare room appraisingly but resisted making any comment. Yalda had spent the last ten days here, struggling to find a way to salvage something from Benedetta’s pointless death.

She said, “We need to be more careful with everything we do. We should always be thinking of the worst possibilities.”