Appendix 3:

Vector multiplication

and division

The travelers on the Peerless have developed a way of multiplying and dividing four-dimensional vectors, turning these vectors into a fully fledged number system like the more familiar real and complex numbers. In our own culture, this system is known as the quaternions; it was discovered by William Hamilton in 1843. Just as the real numbers form a one-dimensional line and the complex numbers form a two-dimensional plane, the quaternions form a four-dimensional space, making them the ideal number system for four-dimensional geometry. In our universe the distinction between time and space prevents us making full use of the quaternions, but in the Orthogonal universe the geometry of four-space and the arithmetic of the quaternions fit together seamlessly.

In the version used on the Peerless, the principal directions in the four dimensions are called East, North, Up and Future, with opposites West, South, Down and Past. The Future direction takes the role of the number one: multiplying or dividing any vector by Future leaves the original vector unchanged. Squaring any of the other three principal directions—East, North and Up—always gives Past, or minus one, so this number system contains three independent square roots of minus one, compared to the single square root of minus one, i, in the complex numbers. (Of course squaring the opposite directions—West, South and Down—also gives Past, just as in the complex numbers squaring –i also gives minus one, but these aren’t counted as independent square roots.)

Multiplication in this system is non-commutative: a × b generally isn’t the same as b × a.

Every non-zero vector v has a unique reciprocal or inverse, written v-1, which is the vector for which:

For example, East-1 = West, North-1 = South, Up-1 = Down and Future-1 = Future. In the first three cases the inverse of the vector is its opposite, but that’s not true in general.

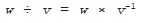

When we divide vectors, w ÷ v is just multiplication (on the right side) by v-1:

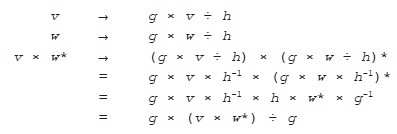

Because multiplication is non-commutative, we need to be careful with the order of vectors when we take inverses or perform division. Taking the inverse of two or more vectors multiplied together entails reversing their order:

This reversal is necessary to ensure that the original vectors come together in the right sequence to give a final result of Future:

Similarly, when we divide by a product of vectors we need to reverse their order:

Although the tables only give the results for multiplying and dividing the four principal directions, the same operations can be applied to any vectors at all (with the exception that you can’t divide by the zero vector). A completely general vector can be formed by adding together various multiples of the principal directions:

Here a, b, c and d are real numbers, and they can be positive, negative or zero. Let’s define another vector, w, using four other real numbers, A, B, C and D:

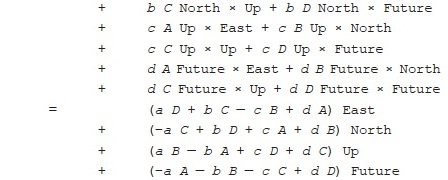

We can multiply v and w together by following the ordinary rules of algebra, taking care with the order in which we write the products of vectors:

The length of a vector can be found from the four-dimensional version of Pythagoras’s Theorem. We write the length of the vector v as |v|, and it is related to the size of its components in each direction by:

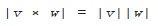

When two vectors are multiplied together, the length of the resulting vector is just the product of the lengths of the original vectors:

Given a vector v it’s often useful to talk about its conjugate, which we write as v* and define as the vector whose components in the three space directions are the opposite of those of v, while its component in the time direction is exactly the same as that of v:

Multiplying a vector by its own conjugate gives a very simple result:

Since the direction Future acts like the number one in this system, if v has a length of one its conjugate v* will also be its inverse, v-1. If the length of v is not one, we can still find its inverse from its conjugate by dividing by the square of its length:

Because of this close relationship between the conjugate of a vector and its inverse, it’s not hard to see that if we take the conjugate of a product of vectors we need to reverse their order, just as we do with the inverse:

The Future component of the product of one vector with the conjugate of another, v × w*, carries some useful geometric information about the two vectors:

The quantity on the right hand side of the first equation, where we multiply the four components (a, b, c, d) of v and (A, B, C, D) of w and add up the results, is known as the dot product of the two vectors. As the second equation shows, it depends only on their lengths and the angle between them.

Any rotation of four-dimensional space can be achieved by fixing two vectors whose length is one, say g and h, and then multiplying on the left with g and dividing on the right with h. So the vector v is rotated by:

For example, a rotation that swaps North and South and also Future and Past, while leaving all directions orthogonal to these unchanged, can be achieved by setting g = South and h = North.

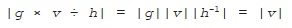

How can we be sure that this operation really is a rotation? For a start, it’s easy to see that the length of v is unchanged, since |g|=|h|=|h-1|=1 and:

We can also look at what happens to the angle between two vectors when we perform the same operation on both of them, by looking at the effect on v × w*:

The Future component of v × w* is left unchanged by this operation, since g × Future ÷ g = Future. And since the Future component of v × w* determines the angle between v and w—along with their lengths, which we know are unchanged—that angle is also unchanged.

All rotations that involve only the three dimensions of space can be achieved by restricting the original formula to the case where h = g:

For example, rotating everything by half a turn in the horizontal (North-East) plane can be achieved by setting g = Up.

Two other particular kinds of rotation occur when we set h = Future, which amounts to simply multiplying on the left by g:

and when we set g = Future, which amounts to simply dividing on the right by h:

Both these operations will always rotate in two orthogonal planes simultaneously, and by exactly the same angle in both. For example, multiplying on the left by East will rotate by a quarter-turn in both the Future-East plane and the North-Up plane.

Consider a rotation specified by g and h that transforms vectors according to the usual formula:

There are two other kinds of geometrical objects that can be described by quaternions, but which are not vectors because they obey different transformation laws when the same rotation takes place:

These curious objects are known as “spinors”: l is a “left-handed spinor” and r is a “right-handed spinor”. In our own universe the mathematics of spinors isn’t quite as simple as it is in the universe of Orthogonal, but it’s very similar, and in both universes spinors play a crucial role in describing the way certain fundamental particles behave when they’re rotated.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ