Chapter Five

1950

Thibaut has always said “Fall Rot” in English: an injunction; two verbs, or a noun and a verb; seasonal decay.

“Case Red,” Sam says. “It’s German. I think it’s something big.” She watches him closely. “You’ve heard of it,” she says.

In the economy of rumor, the partisans of Paris are always listening for stories of their enemies. Of any mention of Rudy de Mérode, of Brunner, of Goebbels and Himmler, of William Joyce or Rebatat or Hitler himself. Myth, spycraft, bullshit. “What do you know about someone called Gerhard?” Thibaut says. That name he has heard once, and once only, when the dying woman whispered it to him.

“Wolfgang Gerhard.” She says it slowly. “Nothing. But I’ve heard of him. A Wehrmacht deserter sold me that name at the border. He said it’s turning up in the chatter. Along with Fall Rot. Which I’d already heard of, Fall Rot, from a man in Sebastopol. That’s a bad place now. Full of devils.” She smiles oddly.

“He’d been into Paris, this guy, and got rich on what he brought out,” Sam says. “He didn’t care about Ernst, Matta, Tanning, Fini, he just wanted things. He had one of you-know-who’s telephone, that was…” Her hands describe it. “A lobster. With wires. If you held it to your ear it would grab for you and get its legs tangled in your hair, but it could tell you secrets. It never said anything to me. It didn’t like me. But this guy told me it once whispered to him, ‘Fall Rot’s coming.’”

“That’s why you’re here,” says Thibaut. “To find out about this Fall Rot. Not to take photographs.” He feels betrayed.

“I am here for photographs. For The Last Days of New Paris. Remember?” She is playful in a way he doesn’t understand. “And to find a few other things out, too. A bit of information. That’s true. You don’t have to stay with me.”

Thibaut beckons the exquisite corpse through the dust of ruins. Sam flinches at its approach. “They’re chasing you,” Thibaut says. “You got a picture of something that got the Nazis worked up enough to track you. What is it has them so worried?”

“I don’t know,” she says. “I have a lot of pictures. I’d have to get out to develop them to figure it out and there’s more to photograph first. I can’t leave. I don’t know what’s going on yet. Don’t you want to know about Fall Rot?”

What Thibaut has wanted is out. To outrace those who follow, now maybe to find whatever image in Sam’s films holds some secret Nazi weakness, to use it against them. But to his own surprise something in him, even now, stays faithful to his Paris. He’s buoyed by the thought of Sam’s book, that swan song, that valedictory to a city not yet dead. He wants the book, and there are pictures to take. When he tries to think of leaving, Thibaut’s head gets foggy. It’s madness, but Not yet, he thinks, not before we’ve finished.

The book is important. He knows this.

He imagines an oversized volume, bound in leather, with hand-drawn endpapers. Or another, rougher edition, rushed out by some backstreet press. Thibaut wants to hold it. To see photographs of these walls on which the crackwork whispers and scratch-figures etched with keys shift; of the impossibilities he has fought, that now walk with him.

Are they hunting images, then, as well as information about Fall Rot? Whatever else, Thibaut decides, yes, they are.

He follows Sam north over a spill of architecture. Refit vehicles still line the streets, too-big sunflowers push their way through buildings, a quiet partisan leans cross-armed over a rifle in a top-floor window, watching them. She raises her hand to Thibaut in a wary salute that he returns.

Sam photographs. They sleep in shifts. At dawn a great shark mouth appears at the horizon smiling like a stupid angel and chewing silently on the sky.

Women and men committed to no side, to nothing except trying to live, have taken up paving stones and plowed up earth underneath. They farm amid changeable ruins, fighting Hellish things and feral dreams. They have made front-room schools for their children in townlets of a street or two, keep barricades up.

One such is close to where a house has gone. By their path, where the cellar was, the hole has filled with sodden grit. Thibaut slows here, can feel something. He stops Sam. He points. There are wet bones in the pit.

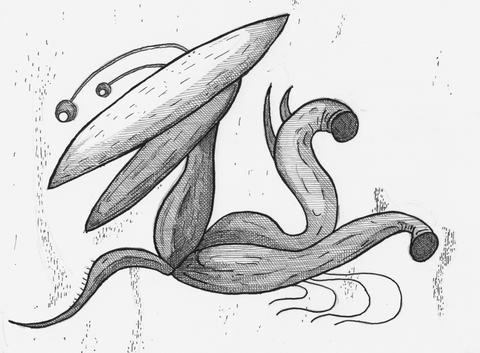

The travelers stay still and something twitches in the sludge. Snares of tubular parts tangle, untangle and rear. Water falls with a rushing sound away from a big vicious elliptical head rising, now the ambush has failed.

It is a sandbumptious, an ugly thing torn from an English painting. It eyes them with eyes on bobbing stems. Judging by the remains around it, it eats stragglers and scrawny horses, like most of its kind.

Sam takes a picture of the predator rising in the muck, and hissing. When she’s done, Thibaut braces his rifle on the remains of a wall. He focuses from his core.

His aim is not very good, but his focus can enhance his fire, his techniques are powerful, and the proximity of the exquisite corpse helps him. When he shoots his bullets slam into the hole and its inhabitant and the wallowing animal bleats and all in a rush, a single flame, at the wrong scale like the tip of a giant matchhead, takes it and goes out.

There is a burnt-out smell. The manif is dead.

As Thibaut and Sam walk on someone shouts “Hey!”

Wary faces rise into view above the nearby barrier. A tough-faced woman with her hair under a scarf throws Thibaut a bag of bread and vegetables. “We saw what you did,” she says.

“Thank you,” says a younger man in a flat hat, looking down his shotgun, “and no offense, but fuck off now, and stay away.” He watches the exquisite corpse.

“This?” Thibaut says. “It won’t cause you any trouble.”

“Fuck off and keep your Nazis away.”

“What? What did you call me?” Thibaut shouts. “I’m Main à plume!”

“You’ll bring them here!” the man shouts back. “Everyone knows you’re being hunted!” Sam and Thibaut look at each other.

“You heard of Wolfgang Gerhard?” Sam shouts. The young fighter shakes his head and gestures them away.

The wind explores the buildings. They hear firefights in distant streets. Thibaut and Sam descend a series of great declivities cracked in the pavement, that Thibaut realizes are the footprints of some giant.

Near the boulevard Montparnasse, Sam checks her charts and journals in the hard sunlight. An old woman watches Thibaut from a doorway. She beckons and when he comes to her, she hands him a glass of milk. He can hear a cow lowing in the cellar.

“Careful,” she says. “Devils are around.”

“For the catacombs?” he wonders. Their entrance is nearby, by the tollhouses called the Barrière d’Enfer.

She shrugs. “I don’t think even the Germans know what they’re doing. The observatory’s close,” she says, “and it’s full of astronomers from Hell. Round here when they look through the telescopes we see what they remember.”

The milk is cool and Thibaut drinks it slowly. “Can I do anything for you?” he says.

“Just be careful.”

In Place Denfert-Rochereau, the Lion of Belfort has disappeared from its plinth. Surrounding the empty platform where the black statue used to stare stiff-legged are now a crowd of stone men and women, all with the heads of lions.

Thibaut is happy among those frozen flaneurs. The exquisite corpse murmurs beside him.

Sam is agitated. She won’t or can’t come close, will only just enter the square. She takes pictures of the motionless crowd from the edge and watches him with a curious expression.

Élise, Thibaut thinks. Jean. You should be here. For the first time since the Bois de Boulogne he feels as if he is somewhere that he has fought for.

He should have played his card. I killed my friends, he thinks.

What treachery against the collectivism, the war socialism of the Main à plume, keeping the card for himself. He doesn’t even know what it would have done. But play is insurrection in the rubble of objective chance. That was the aspiration, the wager of the Surrealists trapped in the southern house.

“Historians of the playing card,” Breton said, “all agree that throughout the ages the changes it has undergone have always been at times of great military defeats.” Turn defeat into furious play. The story had reached Paris with its manifs. Breton, Char, Dominguez, Brauner, Ernst, Hérold, Lam, Masson, Lamba, Delanglade, and Péret, purveyors of the new deck. Genius, Siren, Magus usurping the pitiful aristocratic nostalgia of King, Queen, and Jack. Père Ubu the Joker, his spiraled stomach mesmeric.

The cards were made and lost, and sometimes found again. If the war stories were true, a bird-faced Pancho Villa, Magus of Revolution, played by some Gévaudan militant, had saved his fighters from demon-baiting soldiers. In 1946, the cephalopod heads of Paracelsus, Magus of Keyholes, rose from the Seine and sank two Kriegsmarine ships. Freud, Carroll’s Alice, the Ace of Flames, de Sade, Hegel, a beetle-faced Lamiel are rumored to be loose.

Thibaut carries the Siren of Keyholes. Victor Brauner’s work. That double-faced woman in snarling jaguar stole. Drawn on paper but transferred by some force, scribbled lines, unfinished and all, to a card.

But Thibaut is too cautious a player. He trudges in guilt. He walks with the exquisite corpse, avatar of mad love, in a week of kindness.

“Tonight,” Sam says. They bivouac in a preserved café. “There’s another picture I need to take.”

Thibaut looks up through the unbroken window and struggles to speak. “How about a picture of that?” he says at last.

The stars are wheeling far faster than they should. The sky is dark gray, the stars yellow, and they are not the stars of earth. They are alien clusters. Abruptly and from nowhere Thibaut knows each constellation—the Alligator, the Box without Locks, the Fox-Trap. They shift in all directions.

Sam is smiling. “The devils must be looking through the telescope,” she says. “It’s like that woman said.” He didn’t know she’d heard her. “That’s the sky over Hell. They must feel nostalgic,” Sam says. “There’s no gate here. It’s hard for anything more than scraps to get in or out. To Hell, from Hell, I mean. All the demons can do is look.”

“Do you have any pictures of devils?” Thibaut says. Sam smiles again.

There are lost Nazis in the Jardin du Luxembourg. Men who sob at some depredation, mesmerized by the Statue of Liberty in the grounds. Its head is gone, just a knot of girders, its up-thrust right hand a gnarl. Protruding from the iron chest is a corpulent flesh eye. It blinks. One soldier calls out a prayer, in German, then French. He is hushed by his comrades.

Thibaut and Sam creep by them in the hedgerow. The exquisite corpse fades in and out of their company, always returning. It accelerates through the overgrowing gardens, through thickets and rosebushes, its caterpillar rearing, to where tall railings at its edge are spread like the tines of a ruined fork.

Night comes with gunfire. The beige and black shutters of rue Guynemer are bloody. Sam does not take rue Bonaparte but smaller streets, away from the lights and engine sounds of someone’s excavations. The Bureau of Surrealist Research is nearby—long-closed but haunted with emanations from those early experiments, cabinets of juxtaposed equipment. The exquisite corpse is energized here.

This is a contested zone. In the rue du Four they hide at the sounds of shouted German. “There are bases nearby,” Sam whispers. The Hotel Lutetia where Nazi officers are stationed, the Prison du Cherche-Midi where political prisoners become experiments and food for terrible things.

“Where are you taking us?” Thibaut says. When he sees the spire of a church at the end of rue de Rennes, he abruptly knows the answer.

“You can’t get in,” he says. He wants to be wrong.

“Neither can you,” Sam says.

Two of the five corners of the junction they reach have slid into building-dust. Where rue de Rennes meets Bonaparte, a great rock, like something split from a mountain, hangs just above the ground. The church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés is still a church, and it looks untouched. And there, on the fifth corner, is Les Deux Magots.

The café’s green awning flaps frantically, pushed outward by a rushing wind from within. Around it are tables and chairs, all heaving up and suspended as if about to fly away, then spasming back to their positions on the ground. Up again, head height, and back. As they have jumped for years.

The windows are blown out repeatedly, surrounded by broken glass that twitches and snaps back into the panes then out again, repeatedly, an oscillating instant of combustion. The café rumbles.

Sam walks heavily toward it, into the empty road around it. It looks as if the air exhausts her, as if she walks against a gale. She stops, gasping, still meters from the entrance. The air rushes in Thibaut’s ears.

It was from here that the S-Blast came.

And in all the years since, this famous ground has been impenetrable. No one has been able to push through the windless windlike force it extrudes, its own memory of its explosion.

“I know you want a picture,” Thibaut shouts. “But how can you get in there…?”

She points.

The exquisite corpse is walking forward. Continuing where they can’t. The old-man face sniffs the air, the steam train’s plume streams backward. It recognizes this place, some stink of something here.

Thibaut’s insides are boiling. Sam shoves him after the manif. It strides without effort through the outer fringe of glass.

“That thing won’t let me get close to it,” she says. “You, though…”

“I can’t take your picture for you!”

“I don’t want a fucking picture, you fool,” she says. “There’s something in there. Bring it out.”

What? What is she asking me?

Am I doing this? Thibaut thinks. I can’t be.

But not only is he grabbing the cord that trails the ground behind the manif, and winding it around his wrist, to link himself to the exquisite corpse, but now he is running, shoving his way toward it, putting his hands on its metal body.

Thibaut is drunk on whatever streams out of that place. He walks with this most perfect manif, this ambulatory chance, like the towering exquisite corpse on the grounds where his parents died, that first manif he ever saw, a terrified boy, that would not hurt him.

Glass shatters unendingly but Thibaut is safe and can force himself on in the corona of the manif’s presence. They pick their way together between tables and chairs, pushing, Thibaut gasping in hot air, into Les Deux Magots, inside.

A room full of darkness and light, glare and black, heat and soot, and Thibaut can hear his own blood and the drumming of wood. His face streams with heat. His eyes itch. The tables are dancing on their stiff legs. They somersault endlessly at the point of an explosion.

There are bodies. Skeletons and dead flesh dancing, too, in the same blast, meat ripping from bones and returning to them. The exquisite corpse steps like a dainty child through a carnage of burning waiters, and Thibaut follows, fighting for breath, on his mission again.

The kitchen is full of a storm of burst plates. At its center is someone long-dead. He is a ruin.

A tough, wiry young man, whose glimpsed face snarls and burns up and whose bones burst from him in twitching repetition, his grimace dead pugnacity then dead pain then the rictus of just death, again and again, too fast to follow. He moves like a blown-up rag doll as fire and devilry and shrapnel flay him in a cloud of shards. His hand is on a metal box, it blossoms extruding wires, paper, light. It, too, bursts forever.

Out of it comes, had come, would come the blast.

The exquisite corpse trembles, this close to the point. A dream straining against what made it into flesh, reaching, with limbs like industry, for the bomb.

As it takes the exploded box from the hand of the dead exploder, Thibaut hears Sam scream his name.

Going out is so much faster. The manif and Thibaut half run, half fly.

Sam is waiting as close as she can come. She shouts in delight to see them reemerge. As they approach her she shouts again, eager and loud, at the sight of what the exquisite corpse carries.

But the bomb is strewing parts as it comes, and nothing is happening.

The box is collapsing and the explosion does not. Behind them the room continues to blow endlessly apart.

Thibaut and the manif run into the last of the light and Sam stands in the road with her camera out and Thibaut realizes there is a wall of smoking thorns around her, a defense from somewhere, already withering, and at the edge of the junction, Thibaut can see Nazi soldiers gathering.

Something is coming. The street trembles. There is a booming as if things are falling out of space.

“Give it to me!” Sam bellows as they run.

But the box is still dropping components and wires and now its case is falling apart. Sam reaches toward the manif she does not like to touch, grabs it from the exquisite corpse’s hand.

It scatters into nothing, and is gone. Sam screams a long scream of rage.

Mortars streak over them and take down buildings to block their way. Sam and Thibaut veer. The exquisite corpse does things to physics and they blink with the twists, and ahead of them now is the river and in it the Île de la Cité, and they keep running east along the riverbank on the Quai des Grands Augustins and across from where the Palace of Justice once was and where there is now a channel of clear water that spells something from above, and where sawdust swirls from the windows and doors of Sainte-Chapelle, a landscape of choking drifts and sastrugi at the island’s edge.

The exquisite corpse is ahead of them. It lurches left onto the Pont au Double, leads them over the bridge. It is as if Paris ushers them in. To the island, to where Notre-Dame looms.

Since the S-Blast the squat square towers to either side of its sunburst central window have been industrial silos, tall and fat, crudely hammered metal. One seeps bloody vinegar from imperfect seals: the air they enter is full of its sour stink, the ground below wet and fermented. Through the wire-strengthened windows of the other tank is a thick pale swirl. It’s said that it contains sperm. Thibaut has often begged the sky to bomb it.

He barely sees it now. The manif takes them right, through the tangled wasteland of the gardens behind the church, and there at the furthest tip of the islet the Pont de l’Archevêché back over to the south side and the little bridge to neighboring Île Saint-Louis are both gone. Nothing but rubble in the river. There is nowhere to go.

They turn. The mud shudders. “They’ve found us,” Thibaut says.

Out of the darkness by the buttresses of Notre-Dame comes a dreadful thing.

“Christ,” Sam says. She lifts her camera. She looks almost exultant with fear. Thibaut shouts without words at what approaches.

A walking jag, a huge, broken white shard.

Aryan masterlegs, muscled in that Reich way, kick up dirt. At the height of a third storey is a waist, above which is what is left where a great body broke, a crack and a massive headless ruin. The right side is a crumbling stone slope, the left the remains of the torso that ascend to an armpit where one stump of biceps still swings.

At the thing’s feet scurry Wehrmacht and SS men. A familiar jeep in a gust of scab-colored smoke.

“What in hell is that?” Thibaut shouts. Fall Rot? he thinks. Is this staggering splinter the project?

“Nothing in Hell,” Sam says. “It’s a manif. A brekerman.”

“Breker?” shouts Thibaut. They got one of his to move?

Arno Breker’s looming, kitsch, retrograde marble figures stare with vacant stares of notional mastery. Ubermensch twee, even in Paris they have all always been stubbornly lifeless, Thibaut has thought. But these legs are stamping closer.

Once it must have been a white marble man taller than a church, clapping stone hands; now it is cracked and split and half gone and still walking. Can living artwork die? Can it live, before it does?

“They got it upright again,” Sam whispers.

“Again?”

The camera clicks. The ruins of the brekerman rock back as if the sound has buffeted it. It steadies itself with its half-arm, comes forward. It stamps down trees and begins to run.

The soldiers follow, rifles up. The jeep chutters. In it is the driver they saw before and the man in full church regalia, two others in plain clothes. This time Thibaut can see the priest’s heavy, lined, debauched face, and he knows it, from news reports, from posters.

“Alesch,” he shouts. Alesch himself. The traitor-priest, head of the city’s demon-tilted church.

The foot soldiers run at Thibaut and Sam and the exquisite corpse. The broken Nazi manif comes.

Thibaut fires a useless shot. The stone legs raise a stone foot. He gazes dumbly up at it and sees that the thing is most lifelike on its underside, all folds, verucas, gnarls. It stamps. He leaps with pajama-aided bravery. His skirt parachutes and the filthy fabric flaps. Bullets hit him but the cotton hardens.

He shoots midair. Not at the broken manif but past it, and over the infantry, at the jeep behind them all. The driver jerks and spurts blood, and as the car veers the exquisite corpse reaches from somewhere and hauls Thibaut back from danger, taking his breath all out of him. It huffs, and the two closest soldiers fold away with wails into nothing, leave pencil sketches of themselves where they were standing. Thibaut sees the jeep spin and spray earth and slam with an ugly burst of metal into the church’s side.

Those brekerman legs run forward and with a great swing, kick the exquisite corpse in the center of its pile-up self. The Surrealist manif staggers mightily and sways and sheds bits of itself. Things wheel in the black sky.

Sam is behind an outcropping of wall, pinned by fire and blasts of Gestapo magic. She is aiming her camera, again, and Thibaut sees that what goes between it and the soldiers is a jet of bad energy. She takes their picture and blows them away. She takes a picture of the brekerman legs, too, but they brace against the impact and stand tall and come for her.

Coldly, suddenly, watching the broken brekerman withstand and the onslaught of the soldiers, Thibaut knows that even with whatever it is Sam deploys with her lenses, despite the wordless solidarity of the exquisite corpse, they will lose this fight.

From his pocket he pulls the Marseille card. And plays his hand.

The Siren of Keyholes becomes. Between Thibaut and the soldiers and the staggering Nazi manif is a wide-eyed woman, in smart and dated clothes. She is not like a person. The lines of her are not lines of matter.

She gabbles. Thibaut is staring at a dream of Hélène Smith, the psychic, dead twenty years and commemorated in card, glossolalic channeler of a strange imagined Mars. The inaugurated thought of her, her avatar invoking a spirit in a new suit in a new deck. Keyholes for knowledge. She writes in the air with her finger. Glowing script appears in no earth alphabet.

German bullets spray away from her like drops. Smith’s letters crackle and in the sky there is a rushing. The night clouds race. A fiery circle is coming down, coming in, a dream’s dream, a manif of manif Smith’s conjuration of a Martian craft, spinning.

Behind the suddenly stationary marble legs, Thibaut can make out the priest and another man stumbling from the smoking car. They retreat, supporting each other, further and further back as he aims at them, getting away from him, out of sight, and though he fires Thibaut cannot pay any more attention, because now the cartomantic Smith is pulling into presence the crafts of more Martians and troll-like Ultra-Martians. Her extra-terrestrial contacts exist, at last, in this moment, and they are descending, tearing into the air, firing. The Smith-thing exults.

Bolts burn, twist, melt metal. Fire descends and holes the earth. A fusillade out of the sky engulfs the Nazis and their smashed manif giant. There is a sound and light cataclysm.

And, at last, quiet and dark.

The sky is empty. Smith is gone. The card is gone. The wet towers of Notre-Dame quiver. Vinegar spurts where one’s seams are buckled.

Where the dream Martians attacked, the ground has become a glass zone. Dying people twitch between the brekerman’s feet. The legs are pulverized, the marble feet charred. They do not twitch. They sink slowly into vinegar mud.

Sam runs past the exquisite corpse. It trembles, wounded but upright. She is taking pictures, touching things, prodding smoking remnants. Her camera is a camera again. She reaches the buckled car and without seeming effort wrenches open the door by where the driver lolls. She rummages within.

“Look,” she calls to Thibaut.

“Hold on, be careful,” he says. She yanks a smoking briefcase from the man in the passenger seat and holds it up so Thibaut can see on it the letter K. She holds up something else, too, something twisted, three broken legs like another, wounded, Martian.

“It’s a projector,” she says as he approaches.

The passenger is pinioned and crushed, spasming and breathing out gore across an absurd little imitation Führer-mustache. He is trying to speak to the driver. “Morris,” he breathes. “Morris. Violette!” The driver’s uniform is a man’s but she is a broad, muscular woman, now a dead ruin filling her bloodied Gestapo clothes. The passenger turns his head, shaking, watching the exquisite corpse as it approaches.

“The priest,” Thibaut says to Sam. “He got away.” With his other plain-clothed colleague. Moved by some uncanny means. “Sam, that was Alesch. The bishop. The traitor.”

The jeep is pouring off bloody smoke. Sam pulls documents from the wreck, more dirty objects, the remains of machines. “Well, he went too fast,” she says. “Left stuff behind.” She pulls out a smoking canister full of film.

“What did you do?” says Thibaut. He kneels, speaks almost gently to the passenger, whom he can tell is dying, too, who stares with widening eyes at the case Sam took from him, at the letter K. “You can control manifs, now? Is that your plan?”

The man wheezes and bats weakly at him as Thibaut goes through his pockets and finds and reads his papers.

“Is that your plan, Ernst?” Thibaut says. “Herr Kundt?” Sam stares at the man, at that. “What is Fall Rot?” Thibaut says.

The passenger coughs through his blood. “Sie kann es nicht stoppen…” he says. You can’t stop it. He even smiles. “Sie eine Prachtexemplar gestellt.” They made a—something.

“A specimen,” says Sam. “A good specimen.”

“A specimen?” Thibaut says. “Of what?”

But the man dies.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ