Epilogue:

And Always Beginning Again

A work of such magnificent proportions may perhaps not find access to many private houses except those of the rich; but it should be the most coveted possession of all public libraries in the United Kingdom, in the Colonies, and at least at the headquarters of every District in India and at her principal Colleges.

(Asiatic Quarterly Review, 1898)

But of course, it wasn't really finished. It never could be, it never would be, and it never will be. One of the infuriating marvels of the slippery fluidity of the English language is that for all of its 1,500 years of history it has been changing, enlarging, evolving: it would continue to do so long after the 1928 publication date, even as Herbert Coleridge had anticipated it would, when he undertook the beginnings of the task back in 1860.

What was essentially finished, though, was the new Dictionary's structure. In creating it, James Murray had made something that was so good in all its essentials that, no matter how many editions and evolutions the OED would subsequently undergo, Murray's basic plan remained intact. Sir William Craigie, when he came to be Senior Editor on the death of Henry Bradley, remarked, generously, that Murray's form and methods and design `proved to be adequate to the end, standing the test of fifty years without requiring any essential modification'.

The Murray methods would still be firmly entrenched when the first Supplement emerged, five years later, in 1933. There was no doubt but that a Supplement would be made. Those who had bought the complete edition in 1928 were told of it, and advised it would be supplied to them gratis, so long as they had already paid in full. Someone in the Press—possibly it was Craigie, though that is doubtful, since the editors themselves tended to adopt in public a rather modest pose—made a suitably Grandisonian announcement:

The superiority of the Dictionary to all other English Dictionaries, in accuracy and completeness, is everywhere admitted. The Oxford Dictionary is the supreme authority, and without a rival. I t is perhaps less generally appreciated that what makes the Dictionary unique is its historical method; it is a Dictionary not of our English, but of all English; the English of Chaucer, of the Bible, of Shakespeare is unfolded in it with the same wealth of illustration as is devoted to the most modern authors. When considered in this light, the fact that the first part of the Dictionary was published in 1884 is seen to be relatively unimportant; 44 years is a small period in the life of a language. I t is, however, obviously desirable that aeroplane and appendicitis should receive due recognition. A supplement is accordingly in preparation, the main object of which will be to include words which were born too late for inclusion. Copies of the Supplement will be offered free to all holders of the complete Dictionary. 1

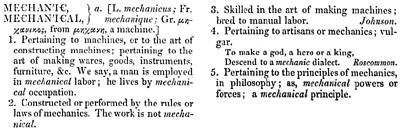

Four centuries of definitions

Robert Cawdrey: Table Alphabeticall (1604)

Samuel Johnson: Dictionary of the English Language (1755)

Noah Webster: American Dictionary of the English Language (1828)

Oxford English Dictionary (1928)

OEB third edition, draft entry (December 2001)

And so in due course all these modern words were included, and the histories of both these and scores of words which deserved more amplification or explication—or which had evolved new meaning in the years between—were duly inscribed. Most related to technologies that had not even been imagined when Coleridge and Furnivall sat down to work, as Craigie wrote—words connected to biochemistry, wireless telegraphy and telephony, mechanical transport, aerial locomotion, psycho-analysis, the cinema. In the end, 867 pages accommodated them all. The inclusions began with the use of the letter A to denote the highest attainable mark given in American schools (the phrase straight A is there as well: 1897 for the first use of A, 1926 for straight A). And they ended with the word zooming, defined as `making or accompanied by a humming or buzzing sound', and first noted in a July edition of Blackwood's Magazine in 1923.

The word pacifist is in the Supplement too. Some critics had earlier written of their disappointment in discovering that `though of decent parentage and respectable antiquity' it was a word that for some mysterious and perhaps politically sinister reason `found no place in the OED'. But the truth was far simpler: the word had simply not been quoted in any published material until the year 1906—even though pacify had been around since the fifteenth century and pacific since the sixteenth. The notion that Murray had overlooked it because quotations that included pacifist were destroyed with the other Pa slips in the southern Irish barn does not stand up: lexicographers have scoured the literature ever since, and it is an Edwardian neologism, pure and simple.

African was in the Supplement, now that Murray had taken his hostility to the word with him to the grave. The forlornly misplaced bondmaid was there, its slips having been found lurking under a pile of books in the Scriptorium long after the B volume had gone to press. Television was there (in the 1928 edition it was too, but with the caveat `not yet perfected'). Radio was fleshed out (earlier there had been merely a passing reference, taken from TitBits, to a Mr Marconi and `his radio or coherer', which transmitted wireless telegraphy). And radium was properly included too—`a rare metallic element … Curie … 1898 … atomic number 88'. Nary a mention of tobacco tins or squint-eyed rats; nothing untoward had crept into the definition.

The only notable omission is not a word, but a listing in the Preface: for the first time since 1884 there is no mention anywhere of either Miss Edith or Miss E. P. Thompson, of Liverpool, Reigate, and Bath. The Dictionary had outlived them, as it would eventually outlive all who helped to make it. And as it always will.

And so there, with its thirteen majestic, gold-blocked dark blue cloth and clotted-cream-coloured paper-covered volumes, the Oxford English Dictionary duly stood guard over the tongue for the next 40 years. It had taken 76 years and had cost £375,000 to get to this point—though nobody at Oxford had a real idea of what the monetary figures really meant: overheads had never been included, and the value of money had changed beyond all reason. The Dictionary was no money-spinner, that was for sure—the coincidence of the Supplement's publication with the Great Depression limited still further any sales which might optimistically have been predicted.

The new Delegates' wonderfully old-fashioned Secretary, R. W. Chapman—a man who never rode in a car nor ever used a typewriter or a fountain pen—ordered up 10,000 sets of the complete Dictionary in 1935. It was supposed they would endure for all time, and there would never be the need to print again. At the outbreak of the war in 1939 there were 6,000 of them left, and it was thought that if the worst came to the worst they could be used as some kind of air raid shelter, at least as efficacious as sandbags and, for Oxford people, rather more suitable.

Once the debris of war had been cleared away and the dreaming leisure of peace began to settle back onto Oxford, the single admitted deficiency of the OED, one common to any dictionary of English—the fact that it was always bound to be out of date— was addressed once more. A further clutch of supplements were planned, this time under the editorship of a genially energetic New Zealander, Robert Burchfield, who took a suite of nondescript offices in a house near to the Press, in Walton Crescent, and eventually installed eighteen staff members there. One formal picture of the team, taken in the same style and the same place (the main quadrangle of the Press) as all the formal pictures of Murray's and Bradley's and Craigie's teams before—shows, in the front row, one `Mr. J. P. Barnes'. Rarely does an OED man become a celebrity beyond his own rather crabbed field of endeavour: but, as Julian Barnes, this particular young editorial assistant was soon to emerge from the harmless drudgery of lexicography to become one of Britain's most celebrated essayists and novelists.

Burchfield's four-volume Supplement, assembled from the vast hoard of words that scattered members of the Dictionary team had been gathering all the while 2 —and which tried to make sense of the vocabulary havoc that was being played by some authors, James Joyce most notable among them—came out at four-year intervals, the first in 1972, the last, dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II, in 1986. Charles Onions 3 was still alive, and helped Burchfield until the mid-1960s. In the end, 50,000 words were added— including (as Burchfield wrote in his final Preface to Volume IV) several which their creators helped to define: Anthony Powell, for example, helped with acceptance world, A. J. Ayer with drogulus, Buckminster Fuller with Dymaxion, J. R. R. Tolkien—a former assistant and walrus expert—with hobbit, and the cosmologist Murray Gell-Mann with quark. Psychedelic, coined in 1957, but popular at the time that Volume III was being printed, made it, just in time.

Robert Burchfield, the New Zealand-born lexicographer who created the four-volume supplement to the completed OED, which appeared between 1972 and 1986. He added a further 50,000 words to the amassment of the tongue.

The books that resulted, superficially identical in design and layout to their predecessors, were composed on machines, printed lithographically and bound, not by hand as before, but on a wondrous contraption known as a No. 3 Smyth-Horne Casing-In Machine. Whole quires were sent to Tokyo and New York to be similarly assembled there. And at the same time as Oxford's printing passed from letterpress to lithography, so all the steel-andantimony printing plates that served the OED for decades past were dumped, eventually to be tossed away. A few survive: I still have, mounted in a frame, the plate for page 452 of Volume V, which encompasses the words Humoral to Humour. It was made in 1933. I would like to think that it might have been made in perhaps June 1899 and used to print sheets for the following 70 years.

In 1971, just before the publication of the first of the Supplement volumes, and to help OUP make money out of this enormous enterprise and inject some cash into Burchfield's endeavours, the entire first edition was `micrographically reproduced', its print made near-invisibly tiny so that all thirteen volumes could be compressed into two. The entire OED was thus able to be sold in one big blue box, along with a handsome magnifying glass in a nifty little drawer at the top—and it sold like hot cakes, particularly in America, where book clubs bought it at massive discounts and used it as a free gift to induce readers to join.

One major task lay ahead, however. In 1986 the language as corralled by Oxford was now arranged into not one but three parallel alphabetical lists: the main OED, the 1933 Supplement, and the four-volume Burchfield Supplement. Anyone looking for a word had of necessity to look in three different places. The OED was, in short, a mess. To make some sort of sense, all of the words, no matter how young or how old they might be, had now to be alphabetically integrated with one another, and one complete list had to be created in place of the existing three. The only way to do this—and to ensure that later expansions could take place with ease and without the need to unpick and rewrite all over again— was to take all of the original material and to recast it, from A to Zyxt, by using what in those days was a giant computer.

And so in the mid-1980s, with an enormously generous donation from IBM of computers and staff, with the work of a number of specialists at Canada's University of Waterloo in Ontario, by employing the keyboarding labours of hundreds of men and women who, in a vast warehouse in Florida, had hitherto been accustomed to the assembling of telephone directories, 4 and under the editorial supervision of two brand new co-editors, John Simpson and Edmund Weiner, the entire OED was ripped asunder, retyped, turned into binary code, and then reprinted. It came out on time in 1989 as an immense twenty-volume second edition, which defined a total of 615,100 words, and illustrated those definitions with 2,436,600 quotations. To do so took 59,000,000 words and 21,730 pages, and consumed almost 140 pounds of paper, for every single set of books.

John Simpson, the current editor of the OED, with some of his staff and their electronic versions of Murray's pigeon-hole filing systems. The third edition of the Dictionary, on which Simpson and his colleagues have been working since the 1990s, is due out some time in the early 21st century.

And though that final number might seem merely a facetiously introduced piece of trivia, it does in fact concern John Simpson, who currently edits (with Edmund Weiner as his Deputy Chief Editor) what is being called the Revised Edition. For this will truly be a monster—an OED so massive as perhaps only to be amenable to use on-line. Just as in Murray's time, no-one is precisely certain when it will be finished. It may include a million defined words. It could run to as many as forty volumes. It could weigh in at nearly a sixth of a ton, for each and every set. Each printing would consume a sizeable acreage of woodland. The environment would be affected, significantly. Would it be worthwhile? Would everyone like the comfort of knowing there was a beautiful 40-volume book out there? Or would all the world prefer the wisdom of the Dictionary to be purveyed electronically, with no physical harm to anyone or anything at all, and only the intellectual benefits deriving from all those decades of scholarship?

Such are the concerns of those who superintend the cataloguing and describing of our language today—concerns that go beyond the plain demands of learning, that so entirely consumed the lives of all those editors, sub-editors, and assistants who went before.

The pictures of those who began the OED haunt us still: legions of elderly, usually bearded men, formally dressed in tweeds and gabardine, sitting at high desks, pens in hand, volumes open beside them, sheaves of paper in racks and shelves and pigeonholes behind them, a heavy, cloistered atmosphere of academic rigour and polymathic knowledge enveloping and embracing them like the very air itself. Today's images are very different: the men and women are younger, they come to work dressed as they please, they spend their times in brightly lit offices, computer screens are everywhere, telephones warble, modems blink, files are transmitted across oceans in microseconds, queries of all kinds are asked and answered in an instant. And yet the sepia pictures of the times before are still around, high on the walls, talked about, pointed at, revered. It is as if they offer to the editors of today some reassurance that the task upon which they are bent is not much different in its essence from how it was when Herbert Coleridge sat down in Regent's Park, all those years before.

So different now—and yet so very much the same. `The circle of the English language has a well-defined centre,' James Murray wrote in his famous Introduction, `but no discernible circumference.' Those who worked before in London and Mill Hill, in the Scriptorium on Banbury Road and in the Old Ashmolean and on Walton Crescent, indeed found and defined the well-defined centre of the English language. That is all now safely gathered in, and for this all must be eternally grateful. Those who work today, building on these undeniable triumphs of the past, are trying now to catch and snare the indiscernible, ever outwardspreading ripples of idiom and neologism and slang and linguistic invention by which the English language expands and changes, year by year, decade by decade, century by century.

We cannot tell what the editors will be like, will look like, how their working places will be designed or defined, in another 50 years, in another century, or in the next millennium. But the English language will be there for sure. Its centre will remain static and well defined. The circumferential ripples of new-formed English words will become ever larger, ever wider, and ever less well defined: that much is certain. And what is certain too is that humans, being humans, will be on hand as well, in some way or another, as they have been for so long, to catch all these words, to list them all, and to record and fix them all in time, for always.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ