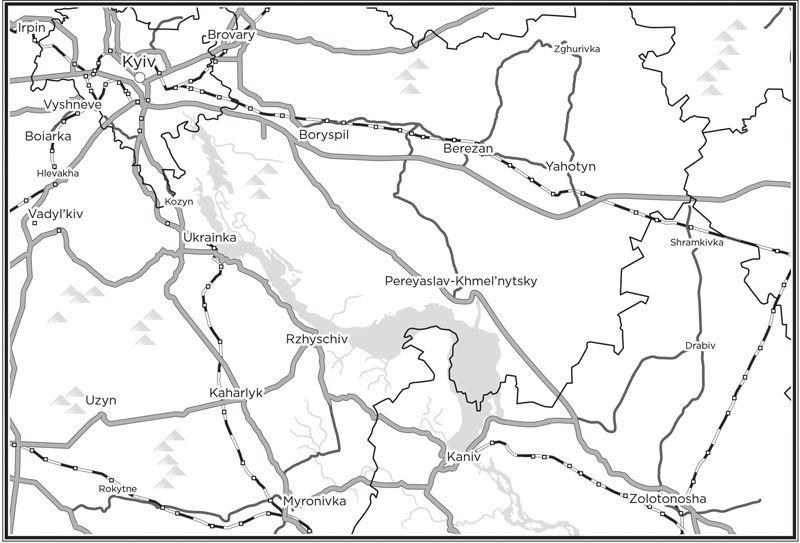

Room 7. The Road to Zolotonosha

The Last Interview by Reporter Goshchynska

Who is he, really—Vadym?

He sits across the table from me, heavy and immovable. He always sits like that, wherever he is, as if he were at home where he owns everything—things, and people, even this unsettlingly empty restaurant, like the setting in a Hollywood horror flick, where he has brought me, after he called, in the middle of the night. It actually looks very much like he owns it, because when we came the doors were locked; he pushed a button I hadn’t seen and as soon as the doors opened, went straight in, not waiting (and not letting me go first, how rude!), pulling the scarf off his neck (Armani, 100 percent cashmere), saying to his door-opening lackey over the shoulder, as he walked, “Valera, have Mashenka lay the table for us.” He didn’t ask for the menu, nor did he ask me what I would like, or whether I would like anything at all, and now here he sits, across the table from me, in the large empty room, like Ali Baba in the thieves’ cave (it is a cave: black lacquer, black leather, backlit surfaces—the all-too-familiar mix of ostentation and grim industrialism that lacks charm but passes for glamour in our latitude). He is capacious and amiable like a shaved, whiskerless walrus, and his breathing is a bit heavy and irregular, as happens to well-nourished men past their prime: an early shortness of breath that, if you’re not used to it, might be taken for erotic arousal. Did Vlada like it perhaps? Or maybe he didn’t breathe like this back then, with Vlada?

“Stay out of it,” he says, looking at me without expression in his eyes, vacant like this restaurant of his (when’d he have time to buy it?). “There are serious people involved. You don’t want any part of it.”

Serious people. Meaning—those who, should you get in the way of their financial interests, might just whack you, another Ukrainian journalist disappeared without a trace. Or you might end up dead in a car accident, or found dead in your own apartment, a suicide. A woman who could not, for instance, get over being fired, why not? A single woman (the boyfriend is not mentioned in the police protocol), without children, all her life in her work, got a pink slip—and that’s it, she couldn’t take it, lost her will to live. And the best thing—no one would even think twice about it: a childless woman is a perfect target, keels over without a thump.

How nice of Vadym to warn me. And I, truth be told, after that ill-advised conversation we had, started to think nothing would get to him. And he, in the meantime, did some legwork, took the time to ask around—how kind of him. There are serious people behind the Miss New TV show, people whose names no one will ever read in the credits. Like the names of the girls who will come to Kyiv for the contest’s preliminary rounds and never make it to the screen, girls who will make it to a completely different place. Not necessarily to foreign brothels even—but right here at home. Someone has to welcome the EU sex tourists and thereby raise the country’s attractiveness-to-foreign-investment ratings; someone has to give a donor a blow job while he is speeding home in his SUV from the meeting at campaign headquarters. Serious people, serious business.

Crying’s the last thing I need right now, but my nose tickles treacherously, and I begin to breathe hard, like Vadym, hard and fast. We sit facing each other, the two of us, and snuffle like hedgehogs on a narrow path. We must be quite a sight. But, dear God, what a nasty feeling this is—to know a crime is about to happen, and not be able to stop it.

How much does it cost—one girl? Those who trade in people—how much do they charge for a soul? Why do I not, after ten years of hard-boiled journalism, know these figures? And why can’t I now bring myself to ask Vadym, who must know?

Who in the hell is he—Vadym?

All I know is that in his previous life, before he became a serious person himself, he graduated with a degree in history, from Kyiv State U. A useful department it was, history: full of country boys straight from army service who paraded around in double-breasted navy suits with Komsomol pins in their lapels and signed up to rat for the KGB for the love of the game. Now the boys are all well past forty and have a new and improved uniform—an Armani suit and a Rolex on the wrist, a real one. And chauffeur Vasya in the SUV—a distant relative from the native village. Who are all these people, and how did they come to manipulate the lives of millions of others—including mine?

“Have some sausage,” Vadym says, nodding at the plate of cold cuts. The slices—beet-red, blood-black, rusty-brown with whitish curlicues of fat—look in the glamorous light like Gothic porn—an installation of vulvas post-coitus. I think I’m going to throw up. Wordlessly I shake my head. Vadym, oblivious, hooks a forkful; a parsley sprig drops from the folded red flesh and remains against the backlit tabletop like an exhibit in a natural history museum. Vadym’s always had a good appetite—a sure sign that the man knows how to enjoy life.

I taste the wine: a 2002 Pinot Noir from an Italian winery with an unpronounceable name. A sunny year, Vadym assured me when his lackey brought out the bottle swaddled in a napkin and, following a commanding motion of Vadym’s eyebrows, proudly presented it to me, like he was a midwife holding up a newborn for the mother to see. Vadym, as is his custom, is drinking cognac, but he knows his wines. People like him know many inessential things that nevertheless make life undeniably more pleasant. Would their life be utterly intolerable without this pleasantness—like a petrified turd under the milk-chocolate cover of a Snickers bar? The long-forgotten face of R., the way he looked after sex, pops up before my eyes, and I take another sip. Indeed, the wine is superb.

“The opposition won’t do anything about this,” Vadym explains, moving more food to his plate. “This show won’t make a loud case, and it’s not good enough for an attack-ad campaign—not much there to work with. This close to elections they want heavy artillery. And your show’s just games, small potatoes.”

“Human lives, actually,” I remind him.

Vadym grows momentarily surly, as if I’d said something tactless, and sets to work on his salmon. I’ve noticed this habit of his before: not responding to an unpleasant remark as if he hasn’t heard it at all. As if the other person farted in public. This is what power really is: the privilege of ignoring anything you find distasteful.

“And if that’s how things are,” I go on farting, “then what’s the difference between your opposition and the goons that are running this country?”

Vadym sizes me up with a quick, short squint over his plate. (Where did I recently see this triumphant look—like a card player dealt a good hand?)

“And what, in your opinion, should it be?”

“It’s only in Jewish jokes that you answer a question with a question. I thought we were serious.”

Vadym smiles mysteriously, then says, “The same difference, Daryna, as always separates people: some have more money and others have less.”

“And you think there are no other differences that separate people?”

“In politics—no,” he says firmly.

I can see he is not joking.

“I’m sorry, but what about ideas? Views? Convictions?”

“That was good in the nineteenth century. In the twenty-first—been there, done that.”

“That’s how it is, huh?”

“And you thought?” he retorts, mimicking my intonation in jest—he’s got quick reflexes, like a boxer—and dabs his lips with his napkin: he has large, sensuous lips, almost cartoonish, and they make it hard to notice, at first, what a strong, willful face Vadym has. “All those ideologies that in the nineteenth century set the course for politics for a hundred years ahead have given up the ghost by now. Nationalism is the only one that has survived. And that’s only because it relies not on convictions but on emotions.”

“So did Communism! It relied on one of the most trivial human emotions of them all—envy. Class hatred, in their parlance. Because you can’t make everyone rich, let’s make everyone poor so there isn’t anyone to be jealous of! Isn’t that the way it worked?”

Vadym does not like being contradicted.

“That’s the way, but it ain’t. Remember Marx? Ideas only become a material force when they’ve gripped the masses—remember that?”

“Let’s say I do, so then what?”

“So, no one ever said what came next. And that was the most interesting part, and the Bolsheviks were the first to catch on to it—Lenin really was a genius…. How do you get an idea to grip the masses? The masses never did, and never will, give a flying fuck about ideas, pardon my language—the masses don’t want ideas, they want bread and circuses. Like in ancient Rome, and that’s how it’s always been, and that’s how it will always be. It’s just that, until now, no society has ever been able to give the masses a steady supply of what they want, the economics weren’t there. Developed Western nations today are the first to have come within reach of the ideal: a well-fed citizen sitting down in front of his TV after work with a beer. The running of the country is conducted entirely behind his back; he is only shown talking heads on TV, the floor of the parliament—where people are making speeches, debating, working hard to sway his opinion—and he develops a sense of his own significance, a sense that he matters, that he has a say. So every now and then he goes to vote, casts his ballot, persisting in the illusion that he was the one who elected all those people into office, hired them, that he rules the country. And he is quite pleased with himself—and a person who is pleased with himself will never rebel. That he only cast his ballot for those he saw on TV most often, and at the best angles, never occurs to him. And if it ever does, he’ll dismiss the idea on the spot, because it threatens to topple his comfortably ordered world. Do you follow? You don’t seem to be eating anything…”

“I had dinner already, thank you. So what about those ideas that grip the masses?”

“What I’m telling you is there aren’t any left in big politics. That’s the thing, Daryna. Have some cheese. They’re all illusions of the pre-information age—all those socialisms, liberalisms, communisms, and other what-have-you…. The nineteenth century still believed all that—in the last twitches of Enlightenment. But, you can write four-letter words on a wall all you want—it’s still a wall, and everything’s still behind it. Take the Second World War—it was a clash of two socialisms, the Russian against the German, and who now remembers that? What ideas? Who gives a damn? The masses are not ruled by ideas—they are ruled by certain complex emotions, but even those are not so complex that you couldn’t predict and model them. Self-satisfaction, envy, resentment, fear—you’ve studied psychology, you know this yourself. And ideas in politics—whenever politicians really needed the support of the masses—always had the same function as slogans in advertising: they’re triggers.”

“Meaning—they affect the subconscious?”

“You got it. They mobilized certain complex emotions and locked them into a short circuit. Like with Pavlov’s dogs. You said it right, just then: Communism was a mobilization of envy. Thus, your core constituency is the socially disenfranchised; that’s the base you can count on. Everyone knows the best pogrom squads are made of those who’d grown up being pogrommed themselves. Bolsheviks made good use of the Russian Jewry before they secured their power. You mobilize the base with envy, with the desire for revenge—and intimidate the rest, the passive majority, terrorize them to nip resistance in the bud. And that’s it; you don’t need no ideologies after that.”

“Are you trying to tell me that was the Bolsheviks’ original plan?”

“That, or something else—what does it matter? The main thing was that Lenin made the brilliant discovery: it’s not an ideology that constitutes a material force—it’s political technology!” Vadym enunciates the last word with such gusto you’d think it were edible. “You can feed the masses whatever hogwash you want—today one thing, tomorrow another, and the day after something different yet, without any connection to what came before. Today we’re dismantling the army, tomorrow we’re shooting the deserters; today we’re recognizing Ukraine’s independence, tomorrow we’re installing a puppet government with our bayonets; today we’re giving land to the peasants, tomorrow we’re taking it away. Any maneuver can be justified by the political goal of the moment, and the masses will keep eating it up. But—only as long as you keep pushing the same button. That is to say, engaging the same complex emotions. And you can keep pushing it till kingdom come if you not only have the means of enforcement in your pocket, but also the media—and Lenin didn’t even have television! What you can’t do, under any circumstances, is change the button or the whole machine will explode. Gorbachev tried it—and you see what happened?”

“Vadym, you lost me. Are you talking about political history, or the mechanisms by which criminal groups co-opt political power?”

Vadym cringes, but in a friendly way: he heard my fart this time and is letting me know that in the company of serious people it will not be tolerated.

“I am talking about effective politics, Daryna. Have some cheese; it’s Brie, good stuff, fresh…. Politics is by definition the struggle for power.”

“To what end?”

“What—to what end?” Vadym asks, confused.

“Struggling for power—to what end? To come to it, get it, and sit there? Chase away new contenders? Or is power still a means of implementing certain, forgive me for belaboring the point—ideas? Certain convictions about the way your nation ought to develop and, more generally speaking, about how we can all collectively dig ourselves out from the pile of shit your effective politicians have piled on the human society? I’m sorry, I know I’m spouting banalities here, but I do feel like I’m missing something.”

We have never had conversations like this before, Vadym and I. When he called me out of the blue at ten at night—“Hello, Daryna, Vadym here, gotta talk”—and stunned me by declaring he was coming to get me, I could imagine anything (my first thought was, something’s happened to Katrusya) other than this lecture on the fundamentals of political cynicism in an empty restaurant. If what he really wanted to do was to warn me, he could have done that on the phone. And yet somehow I am not surprised; I am playing right along, dutifully posing my questions. As if I were interviewing him for the cameras. (Do they have security cameras, I wonder?) As if one day I were going to bring this interview before Vlada who stands, an invisible shadow, between us: she is the one who left Vadym to me—like a question to which she failed to find an answer.

Vadym finishes chewing unhurriedly, dabs his lips with the napkin again, folds it neatly, and puts it down beside his plate. Then he raises his eyes to me—a statesman’s weary gaze, a mix of boredom, lenity, irony, and pity.

“Do you think that Bush lost sleep over saving the world? Or Schroeder, after he stuck his country on the Russians’ gas needle? Or Chirac? Or Berlusconi?”

“What’s gas got to do with anything? Even if they’re all rotten bastards it doesn’t automatically mean that…”

“Whoa, now!” Vadym cuts in, beginning to enjoy himself. “What do you mean, what’s gas got to do with it? Power is access to energy sources, my dear! Fuel is the key to world domination—always has been, always will be.”

“I seem to remember hearing this before, somewhere—the thing about world domination…”

Again Vadym squints at me with the directed gaze of an attentive, always internally focused person. (Where, where did I see this look? Night, darkness, reddish reflections of fire on people’s faces…)

“If Hitler’s who you have in mind, his case is actually the best proof that having an idea can only undermine a serious politician. Really, ideas are counter-indicated. Of ideas, poor Adolf, unfortunately, had plenty—and believed in them, to make things worse.”

For an instant, I despair: it’s like Vadym and I are speaking two different languages, using the same words that have different meanings for each of us, and I don’t know how to disentangle myself from this confusion. And he is on a roll, words are spilling out of him, and he is clearly enjoying the process—how smoothly and evenly it all comes out.

“It was from the Bolsheviks that Hitler learned the most important thing—the technology of manipulating the masses. And the button he found was good, too: national resentment, the Weimar defeat complex. Plus the same envy of the socially disenfranchised that the Bolsheviks exploited. And there he had it—the German nation of workers and peasants, and on an order of magnitude more successful, by the way, than the one the Russians had built. If Hitler hadn’t had a brain-fuck, excuse me, on the idea of winning world domination for his beloved German people—and that’s a totally demented idea; no people can dominate the world, only corporations can, and that’s how it has always been and always will be—if he hadn’t had, to put it simply, a bunch of idiotic fantasies in his head, history would’ve have taken a different course. And the US today would mean no more than Honduras. Or, say, New Zealand.”

“So what then, Adolf fucked up?”

Vadym does not share my irony.

“Exactly. Fucked up. There was a reason Stalin couldn’t, until the very last moment, believe that Hitler would attack him. He couldn’t fathom that a politician of that stature could turn out to be such an ideological dickhead, like a green student radical or something. They could have—couldn’t they?—just divided the world into spheres of influence as they’d agreed in ’39, and everything would’ve been fine. A lot less blood would’ve been spilled, too. Back in my university days, I wrote my thesis on the Battle of Kursk—I tell you, that was a horrific business: if you didn’t know better, you’d think the only thing either side cared about was how to kill more of its own soldiers. There you have your ideas.”

“Is there any chance it might matter what those ideas are?”

“Whatever you want them to be, Daryna! In politics, all they do is stand in the way—they’re noise. Trust me; I’ve been handling this shit for years. And without gloves,” he clarifies as if this were some especially sophisticated exclusive he were giving me. “We’re on the verge of a new world order—the status quo that emerged after World War II has long been pushed to its limits, the Yalta epoch has exhausted itself. Think about it, you’re a smart woman. Do you honestly believe that toppling the Twin Towers was the homespun work of a handful of demented Arabs from nowhere? And that Bush, who, by the way, has old family business ties to the Saudi oil sheiks, went into Iraq to save the world? And the apartment buildings blown up in Ryazan when Putin needed to send the Taman Guards to Chechnya, a division recruited from that same Ryazan—is that not the same scenario? Only they did a sloppier job in Russia, and everyone knows that those explosions were FSB’s handiwork. But it’s too late now; the deed’s done. The way to the Caspian oil pipeline’s been cleared—Georgia’s still fussing underfoot, but it’ll be its turn soon. Now one of your journalist people over in the States is making a movie about September 11—trying to prove the whole thing was a political provocation, and that Bush knew about it ahead of time…”

“You mean Michael Moore?” I remember I saw the headline on a news crawl somewhere—about the film’s presentation at the Cannes Film Festival, where I am no longer going. “I wouldn’t think you followed that kind of news. So, is there a hypothesis about who engineered that provocation?”

Again, a quick triumphant flame flares up in Vadym’s eyes—as if he himself were one of the provocation’s authors. “Who it was, Daryna, no one will find out for the next ten to twenty years. Until the new redistribution of the energy-source markets is over. And that Moore guy won’t prove anything to anyone, mark my word.”

“Why do you think that?”

“Because—again—it’s too late! The button has been pushed, the masses mobilized: they were shown very real horror on television, and they got scared. Bunched together into a herd. And no journalistic investigation can now convince them that that was precisely the goal—to have them bunch together into a herd and put their fate in the shepherd’s hands. On the contrary. Now, the more American blood is spilled in Iraq, the more trust there will be for the administration because it is the hardest thing for people to admit that their loved ones died for nothing. Nothing glues a nation together like spilled blood: the USSR was sealed in the same way—by the Great War. And Bush, you can be sure, will get reelected for a second term this fall. That’s the reality, Daryna. And all the talk about liberal democracy, or the Party’s dictatorship, or whatever—it’s all crap, forget it. The politics of today is an amalgamation of the experience of twentieth-century superpowers and the experience of the marketplace, of advertising. An immensely powerful combination, if you know how to use it.”

“Precisely. Orwell wrote about it, back in the day.”

Vadym ignores Orwell like another fart.

“This is a very serious shift, Daryna. A historical one. The masses no longer choose an idea, or a slogan—they are choosing a brand. And they’re not doing their choosing rationally either—they vote purely with their emotions. Bread and circuses? Here you go—public politicking itself becomes a circus! What are presidential debates if not the same old gladiator fights? September 11 is the most successful reality show in history: every soul on Earth who could find a TV set watched it. Putin is a TV superhero now, and seventy percent of Russian women have erotic dreams about him. In Stalin’s days, they threw people in jail for dreams like that. A public politician today is a showman first and foremost, the registered trademark of the company behind him.”

“And the company—who is that?”

“A corporation of those who do the actual governing,” Vadym answers calmly. “The world has always been ruled by such corporations. Only the post-information society is much easier to rule than societies were sixty years ago. He who ensures the best show for the masses wins. He who, to put it bluntly, puts the picture into the TV. Meaning, ultimately, whoever has the most money. And that’s that.”

“You really believe that?”

Vadym smiles. He does have a really nice smile.

“Believing belongs in church. And Daryna, I am used to dealing with things that are real. You just remember that history is made by money. That’s how it’s always been and will be.”

An unpleasant chill begins to fill me, like in a dentist’s waiting room when I was little.

“The Soviet Union had enough money to wipe its ass with it,” I tell him, mustering as much crudity as possible. “And fat lot of good it did them.”

“Whoa there one minute!” Vadym exclaims, astonished. “Half the world under control—that’s not good enough for you? You couldn’t swing a dead cat in the twentieth century without hitting Soviet cash! Take even what happened in ’33—Stalin got the West right where he wanted them when he flooded the world market with all that genocidal Ukrainian wheat! And remember, it was the Great Depression—d’you think Roosevelt just happened to roll over and recognize the USSR exactly then? There’s your fat lot of good, right there. In ’47, Moscow sent grain to France in silk sacks, and French Communists waved those like flags at the elections: look how the working class in the USSR lives! All those Western Communist parties, leftist movement, terrorism, Red Brigades, all the rumbles in the third-world jungles—do you think it all fed and clothed itself? No, dear, the hand of Moscow could be very, very generous when it needed to be. And not a single peep from anyone—so, alright, they let a couple dissidents out, and maybe the Jews stood up for their own, but that’s it; that’s your entire Cold War right there… Americans can tell themselves they won it all they want since it makes them so happy—but they’re living in a fool’s paradise. In reality, if oil prices hadn’t collapsed in the eighties, and if the Politburo hadn’t started squabbling, you and I would still be living in the USSR. You can be sure about that.”

He is talking like a sports commentator reflecting on the rise and fall of some team like Manchester United, and in that regard I also hear something else in his voice: the time-tested ardor of a soccer fan, a boy’s admiration for the forward—the same intonations with which old retired military remember the USSR. There are so many of them—people who are always ready to see all kinds of good in any crime as long as it goes unpunished.

“That’s exactly what I am not so sure about.” For some reason, my voice goes low; shit, could I possibly be nervous? “I know nothing about any squabbling in the Politburo, but as far as I can tell, if one were to try to find a single reason for why the USSR collapsed, it was under the burden of its own lies. All of it, accumulated over seventy years. Because virtual reality—it is this thing, I’m here to tell you, that can hit back very hard if you play with it for too long. You can’t keep lying and maintain your own sense of how things really are at the same time. If you keep ordering a certain picture on TV, you eventually start believing it yourself. Inevitably. And that’s the end of any, as you call it, actual governing—exactly what happened in the USSR. And this Politburo of yours, a corporation of senile old men…”

“It’s not mine,” Vadym grins, warming a glass of cognac in his paws. “But it does fit the definition of a corporation, I’ll give you that.”

That’s praise—as if he were assessing my performance in his mind, like a judge at an art show or a violin recital. Putting pluses in some imagined columns next to my name. And this, for some reason, really pisses me off.

“So then, this corporation of yours was made up of zombies who’d zombied themselves so thoroughly they knew nothing about the country they ruled! They thought Armenians were Muslims—remember that big shot from Moscow who let that drop in Nakhchevan? The FSB still can’t bring itself to believe that Ukraine is independent—they keep waiting for their made-up picture to come back on. Governors, my ass! Like blind butchers in a slaughterhouse.

“Some folks I know interviewed Fedorchuk not too long ago—the head of the Ukrainian KGB under Brezhnev, he’s living out his days in Moscow now—with not a soul to talk to, his son shot himself, wife also committed suicide, and to him it’s all like water off a duck: like they’d catapulted the dude to Mars decades ago, and he just stayed there—spent all his life in virtual reality. By the way, it was on his watch they packed my father off to the loony bin…. And do you know what this mummy remembers before he dies, the most important thing in his life? That he put up a new departmental apartment building for the KGB in Kyiv: made sure all his cronies had a place to live! My jaw dropped when I heard it: what kind of a Gestapo chief is that? I thought he’d at least lash out at the nationalists he used to fight, you know, regret that he didn’t quite finish them bastards off, since now they’ve brought the great country down. But he couldn’t care less—the only reality he had and still has is this one: a departmental apartment building. A family corporation, like the mob. Beyond that, the world doesn’t exist for these people; that’s how they see it—like a picture they chose for themselves, and on which they can push the delete button if they want to. Not much by way of ideas there, you’re right! What kind of government can there be with ideas like that? You’re a historian, Vadym,” I resort to my last argument (like all serious people who didn’t start out as goons, Vadym likes pointing out his former “civilian” vocation).

“You don’t need to be reminded how that corporate country burst, like a soap bubble, every time it came face to face with a reality on which it couldn’t press its delete button. That’s exactly what happened at the beginning of the war, only Hitler helped them out that time, by turning out to be a worse zombie yet—folks took a good look at what rolled into their backyards and went to fight for real. And in our own memory—when Chernobyl blew up: an idiot could see that the system was on its last legs, an idiot would’ve known people should have been evacuated from the contaminated area. But these zombies herded children to the Labor Day parade in Kyiv, and the KGB was running around like the proverbial chicken with its head cut off, desperately recruiting new finks because it ran out of the ones it already had… pressing the same old buttons, as you say. Lies can get you to the end of the world, but they can’t bring you back, thank God. You can’t keep raping reality with impunity; sooner or later it will take its revenge, and the later it comes, the more terrifying it will be. You don’t kid around with these things, Vadym!”

All of a sudden, Vadym starts laughing—with his entire body at once. His monumental bust in its Armani suit coat shudders above the table like Etna, with subterranean jolts; his face contorts pathetically, as if he were chopping onions, and looks so comical that I, too, can’t help smiling—making both of us look rather stupid. Vadym nods to a long-legged, long-necked, and black-clad young woman who has appeared, like a miniature giraffe, out of thin air next to our table. “Ice cream, Mashenka.”

From his mouth, this comes out as warmly as “sausage” did a bit earlier. Mashenka, before disappearing, shoots me, from the height of her triangular face—a Cubist’s dream—a professionally manufactured smile, a mirror image of my own momentary grin, and, at the same time, a sharp, wary look of the territory’s mistress who is about to leave an untrustworthy guest alone with her male: this is mine, don’t touch it. Wow. Did he really find the time to put his stakes down here, too? She’s pretty stylish, Mashenka is; she could’ve been a model… wow again. What about the massaging Svetochka now?

“At least you still have taste,” I tell Vadym vindictively, following his little black giraffe with my eyes as she leaves the room.

He pretends he didn’t hear, and pours me more wine. He does stop laughing, though. Only breathes heavier and louder than before. Exercise, you need to exercise more, Vadym—what kind of shape are you in, breathing like that at your age? While Vlada was alive, he and I always used to be a little caustic with each other, but back then I wrote it off to the natural jealousy every man feels toward his wife’s girlfriend, an owner’s reflex—so now I keep pushing. “You own this restaurant, don’t you?”

“What if I do?” Vadym replies, looking slyly around the brightly lit, black-lacquer cave and squinting like a cat that’s trying to get you to pet him. “Do you like it?”

Now, this is a look I remember exactly where I’ve seen before—that’s what my boss looked like when he waited for me to praise him at his housewarming, signaling at me with his eyes across a giant room full of people: applaud me now, go ahead, applaud, confirm to me that it hasn’t been all in vain—give my marathon swim through shit its long overdue justification.

So is this what Vadym’s brought me here for—to show off his new acquisition, to get my approval—you’re on the right path, comrade? Now I finally catch on to something I should’ve caught on to long ago (for the smart woman Vadym believes me to be, I can sometimes be incredibly daft): for him, I have replaced Vlada in the bar-setter’s role—if I approve, she would have approved, too. And then everything’s okay, and Vadym’s life is back in tiptop shape. That’s what he wants; that’s what he is trying to extract from me. He doesn’t miss a beat, this guy. He’s a bull!

Do you have to be a toothless old hag to stop falling into the same trap—to stop mixing up strength and resilience in men? In every war there is but one law: the strong die and the resilient survive. There’s no special accomplishment in that, no credit to be given them; it’s the genetic programming they were born with—to survive: like the lizard that grows back its tail, or the earthworm that regenerates its lost segments. Vadym, who so recently appeared to be utterly annihilated by Vlada’s death, has put himself back together like the damaged Terminator—by disassembling his dead wife into the various critical functions she performed for him and redistributing them to other women: N.U., Katrusya, several Svetochkas and Mashenkas, to each her own, like in Buchenwald, and only the niche of the bar-setter (“How am I going to live now? She set the bar for me…”), the one to whom you bring your life like homework to be graded, to receive, in return, a clear conscience and untroubled sleep—this extraordinarily important niche in every Ukrainian man’s life has been, for Vadym, unfilled, and he must be feeling a constant discomfort emanating from that spot. No one will tell him the truth now—he’s got too much money for that. But I—I’m always there. I’m Vlada’s closest friend, and I want nothing from him; I’m the perfect fit. And should I be inclined to blurt out something contrarian—well, that’s exactly why he’s given me, completely for free, his very valuable piece of advice: keep quiet.

Now I am supposed to pay him back for this favor, tit for tat, a fair trade! I am supposed to applaud his new acquisition without interrogating him about where he found the dough for the new glam digs (especially right now, when the powers that be are taxing everything that moves to fund their anti-Yushchenko campaign, which is beginning to look like an actual war and not just a publicity war, and Vadym’s ostensibly part of the opposition, if I’m not mistaken, so what fairy godmother waved her wand and conjured this restaurant?). I should praise the interior design and Mashenka and whatever else, whip up a bunch of compliments and ensure for him the aforementioned clear conscience and untroubled sleep. And I should not, God forbid, ask what the hell he wants from this fucking restaurant, and why, once he had money to spare, he didn’t put it—toward his dead woman’s memory, as she had dreamed of doing (“when I have real money, Daryna…”)—into any of the squalid pig-farm barns our museums have become: the National right here, for one, where to this day they can’t give what survived of the Boichuk School the space it deserves; or the Hanenki, out of which you could, if you fancied, lift a Velázquez or a Perugino as easily as canvases out of a crashed car—oh, the list goes on and on! That’s what Vlada would have told him. But I won’t because I don’t have the right to. And he knows that. He knows, and waits, and squints with pleasure in advance—like a cat about to be scratched behind the ear by the mouse he’s caught. How can you not love the guy?

“You, Vadym, are an amazing piece of work.”

He instantly takes this for the compliment he feels due, swallows said compliment like a morsel off his plate—gulp!—and brightens up so sweetly that only a complete bitch wouldn’t feel disarmed. “You shouldn’t have turned down the dinner! My chef has three international diplomas, beat a French guy at a contest in Venice last year.”

Dare I hope he is not about to take me to view those diplomas?

“As I said, I’ve eaten already.”

“And now you’re missing out; you can be sure about that. You have to join me for dessert, at least.”

“Uhu, as my granny used to say, ‘you haven’t eaten an ox until someone saw you do it.’”

“Mh-hm,” Vadym agrees, either because he doesn’t get it or because he didn’t quite hear me. “Our grandparents lived through some real tough times, what can you say…?”

And that’s why now we take such pride in what we eat, I think but do not say out loud—1933, 1947—it’s all stowed away somewhere inside us, coded into our cell memory, and the children and grandchildren, delirious with the sudden abundance of the nineties are now busy growing new segments, like the earthworms—catching up for everything uneaten in the generations before them. Only it’s as if there’s been an error in the genetic code, a mutation that’s been selecting for the most resilient, the best at chewing and digesting, and it is now they who fill our city with the petrified refuse of their gigantic intestines: restaurants, bistros, taverns, pubs, diners, and snack bars multiply at every step like mushrooms after the rain, only dentist’s office marquees can compete with the eateries in their intrusive density, and if one were to stroll around Kyiv with nothing particular to do (only who now can go strolling like that, with nothing to do), one might very well think that people in this city do nothing but eat, eat—and have their teeth sharpened so they can eat some more.

R., too, took great pleasure in talking about the delicacies he ate in Hong Kong, and the ones in the Emirates, and others in New York, in some stratospheric establishment where they don’t even give you a menu you just order whatever comes to mind, and don’t ask about the price. “And do they really just get you whatever you ask for?” I asked him. “They certainly do,” R. assured me with dignity. “What if it’s an endangered species? Komodo dragon brains? Siberian tiger steak? Or something more environmentally friendly, perhaps—charcuterie of donor kidneys, chopped out of some Albanians or Mongolians no one bothers to count?” R. laughed. And when I asked him, up front, how many starving people could be fed for the price of that one dinner, he took offense and called it bigotry. Although he, unlike Vadym, wasn’t even a bit heavy.

This is who they are, these serious people—all those who, after the Soviet Union’s collapse, rushed to rake in never-before-seen capitals, first as cash knitted into their undershorts, and later as transfers to offshore accounts—this is who they are: the descendants of a pogrom. The kind of pogrom modern history couldn’t fathom, and which, for that very reason, it failed to see or acknowledge when it happened in its own time, simply pressed the delete button. And now it is too late, they have arrived—the ones who, as Vadym said, make up the best pogrom squads. They have arrived and will take revenge on the new century for the mounds of deleted corpses from the past, spawning similarly deleted mounds of new corpses, and never suspecting that they themselves constitute a mutation—a tool of revenge. Flagellum Dei, the scourge of God (where did I just hear this phrase?). They have magnificent teeth, brand new titanium implants, and are insatiable like the iron locusts of the Apocalypse: they have come to eat, and they will eat until they burst—until their titanium teeth grind everything in their path into dust.

Suddenly I feel so tired, as if all the air had been let out of me. As if he’d sucked me dry, this Vadym—although it is not at all clear how he could’ve managed that. A growing ache buzzes at the back of my head; I try to hold it straight. The black-giraffe Mashenka brings ice cream in silver flutes—his own ice cream, made in house, Vadym continues to brag, from that same wonder chef.

“Taste it, you won’t regret it. Have you ever had homemade ice cream?”

Rich, thick-enough-to-cut-with-a-knife ice cream, yellowish like cream, does have an unusual taste—like the taste of country cooking: something filling, dense, unrefined and fragrant, from an era before plastics. One helping of this is enough to keep you full for a day. Obediently, I say this to Vadym. He nods like a professor happy with a student’s answer on an exam.

“Now this, Daryna,” he suddenly says didactically, “is the reality.”

“What—the ice cream?”

“And the ice cream, too.” He is no longer smiling. “All this,” he looks over his cave again, “and many other things. The ice cream, by the way, is all-natural, made with real milk. No chemical dyes, no GMOs. You know what gee-em-Os are?”

“I’ve seen that abbreviation before…”

“Genetically modified organisms. The ones that are winning a growing share of the world’s food market and our national market as well. Soy beans, potatoes with scorpion genes…”

“Good Lord, why scorpion?”

“So the bugs won’t eat them. And they don’t. But we do, all of Polyssya has been planted over with those potatoes. Western importers are dumping all this shit on us with no restrictions or controls whatsoever; another generation—and we’ll have the same problems with obesity as Americans do today. And in a few more generations on such a diet we might very well start growing tails, or, say, hooves, no one can tell for sure which in advance.”

“Come on, that’s straight out of Hollywood!”

“Yes!” Vadym responds, inexplicably encouraged. “Now we’re getting somewhere. You were so full of fire and brimstone when you were talking about reality and how one doesn’t kid around with it, you almost had me. You’re good! You nailed it, as if from the screen. But what is it—this reality? To listen to you, it’s a… a…” he hesitates for an instant, uncertain outside his regular vocabulary, “a fetish. As if reality existed separately, all by itself.”

“Doesn’t it, though?”

“For some village grandma—it may very well indeed. But you, of all people, ought to realize that reality is manufactured by people. And you can’t draw the boundary anymore between what you call reality and what’s been manufactured,” he slows down again, looking for words: he is not used to abstractions, “realities that have been manufactured by people.”

“Simulacra?”

Damn that silver tongue of mine! This is not a word Vadym knows—and for a few seconds he studies me with the unblinking antipathy of a redneck whose first instinct is to suspect treachery every time he runs into something unknown. (This momentary clash—as if he and I had rammed into each other at full tilt—makes me instantly dizzy; the world, shaken, lurches into motion like sloshing water, and a queer sense of someone else’s invisible presence flickers by, a near presence, somewhere by my side, where I don’t dare turn my suddenly aching head.)

“It’s postmodern theory,” I hear my own voice say, also as if from somewhere beside me. “Media, advertising, the Internet—they are simulacra. Phantom phenomena that do not bear a direct relationship to reality, but together constitute a parallel reality, the so-called hyperreality. A famous theory—Baudrillard wrote about it. He was French.”

“See!” hearing that he, by himself, came to the same conclusions as a famous Frenchman, Vadym regains magnanimity. “That’s what I’m telling you. Just then, when you didn’t believe me, you said, Hollywood, and that’s perfectly normal, that’s a normal reaction. It’s harder now to believe the truth than something made up. Any truth is the result of so many complicated moves and connections, with so many of those moves hidden, that a regular guy could never dream of making any sense of it. And something made up, a fiction—that’s what they call a slam dunk, every time. And the more information there is out there, the more regular people will favor simple solutions.”

“Occam’s razor?”

“That’s it. Tell the public that Kuchma ordered a journalist killed because the man had criticized him—and everyone will believe it. Because that’s what dictatorship always looks like in movies. But if you tell them it was a special operation of several intelligence services, one whose geopolitical significance for the region could be compared to that of the Balkan war—and people’ll look at you like you’re nuts.”

“So was it really an intelligence operation?”

“Doesn’t matter!” Vadym cuts me off, lips holding back a smile that threatens to slither out like a worm, and that same sensation, of a rocked vestibular apparatus, undercuts me again: a splash, a giant mudslide, the solid ground under my feet slipping apart like fissured ice.

He is bewitching me. He is bedeviling me, like a professional seducer, so that I won’t know what to believe—this must be how he gets all the women: by robbing them, step by step, of their footing, turning the ground beneath their feet into shifting gray sand like in that dream Vlada had, and once he has, all that’s left for his bewildered victim to do is to throw herself onto his broad chest: he is a wall of a man, the solitary rock among a fog of phantoms! A powerful erotic move, to be sure, but where, damn it, have I met a man exactly like this before (not R., R. was simpler)—with the same calmly assaulting manner of persuading and subjecting others, even with the same cunning glint of insanity in his eye? (A patient in a faded grayish gown whom I saw looking at me, a fifteen-year-old, in the yard of the Dnipropetrovsk loony bin, grinning as if he knew everything about me—all the worst, the stuff that would never in a million years even occur to Mom who went twaddling on about something pathetic; neither would it occur to her that a visit to my father could evoke in me any feelings different from her own, and that I, boiling with tears of rage, stood there thinking that my mother was a fool and my father had abandoned me, had betrayed me for the sake of his own, terrible grown-up business that was more important to him than I was, and had become this helpless desiccated old man with murky eyes. At that moment, I hated them both, with all the fervor of teenage resentment, and that’s when it hit me, head on, blinding me—the look of that other character who grinned as if he had read my mind, and I went cold—and only later saw what it was he held in his hand tucked under the loose hem of his robe.)

“Take another example,” Vadym pours out more of his sand. “The White House announced that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction—and everyone believed it. And never mind that they still haven’t found those weapons—and, most likely, won’t. They’ll be morons, of course, if they don’t; if it were the Russians, they would’ve planted some right away, and then no one would ever dig up what actually happened. There you have your reality. And you say—bad governors. No, my dear, the effectiveness of a government must be judged according to the tasks that the government sets for itself. The stuff that goes out to the public—that’s not an indicator, you can’t pay attention to that.”

He lied to her, I suddenly realize. He lied to Vlada. I don’t know how, I don’t know what about, but I know it as clearly as if the right switch finally flipped in my mind and the light came on: he lied. And was perfectly effective at it—Vlada lived with this simulacrum for three years and did not notice it. Only close to the end did she begin to suspect something—all her works from the last year of her life were full of a growing premonition of a catastrophe. Her best works, the ones that triggered such a fit of anger in Aidy’s art-worm (I still blush at the recollection of that ugly scene). And not in him alone—few in Ukraine appreciated Vlada’s Secrets, something about the series transgressed the boundaries of the acceptable.

An intimate knowledge of darkness—that’s what they contained. Her Secrets—of darkness made home, warmed by a feminine hand—adorned with flowers and decoupage, like a wolf’s lair hung about with elaborate patchwork quilts, her own darkness. Mixed media, the mysteriously shimmering collages by the girl who stood at the edge of the abyss and looked down with a child’s thrill—until she got dizzy. As I am getting right now.

He is shrouding me in his language, this Vadym—it’s like a cloud of marijuana smoke. I can’t contradict him: I do not, in fact, know anything, let alone have any of the intimate familiarity, about all that hidden machinery of big politics that he keeps hinting at—with passing, shifty references I can’t quite grip; I have no logical crutch I could lean on to help myself scatter this verbal fog—I am only sensing a fundamental untruth hidden in it, and this hypnotic cocoon in which he is ensnaring me is paralyzing my will, as though taking away my command of my own body. The bifurcation point, a phrase from Aidy’s vocabulary, shoots through my mind: this is the point at which women undress for Vadym. Or tell him to fuck off.

And, pretending that Aidy is watching me (and I am savoring, in advance, the story I’ll have to tell him when I get home), I improvise a husky, deep chuckle—in the big, empty dining room, it sounds more defiant than conspiratorial—“Why are you telling me all this, Vadym?”

Oh, what a look he gives me! A man’s look, sizing me up, taking direct aim—a look that’ll make your knees buckle!

“Are you bored?” he changes tack abruptly.

“No, but it’s late already.”

Music begins to play, low. “Hotel California,” an instrumental version. Mashenka must’ve put it on. Must be the way they do things here: put on music for dessert. It triggers the necessary complex emotions in the current object of wooing. Like in one of Pavlov’s dogs.

“Have you got someplace to be?”

“Just tired you know.”

“You’ll sleep in tomorrow. You’re not getting up for work, are you?”

Such a lovely place, such a lovely place, such a lovely face…

“Pardon?”

“Didn’t you resign? You don’t work in TV anymore. You don’t work anywhere, do you?”

God! It’s like my plane drops into an air pocket. Uncontrollably, my jaw drops: what a brilliant tactician he is! One could see what got Vlada, especially in contrast to Katrusya’s father, the newly minted Australian kangaroophile who’d spent the entire span of their marriage on a couch in front of the TV.

“You are well informed indeed. So you weren’t making your inquiries only about the beauty pageant?”

“Does it bother you?” he glows modestly: it’s always nice to knock your neighbor down a rung or two, lest she think too highly of herself.

“You could’ve just asked me—I’m not making a secret out of it. Or do you perhaps think that I could have gone on working there? In full knowledge of what they were doing?”

I hear how weak that sounds—like I’m making excuses. In this game, as in any kind of business, the what is not important, and neither is the how—the important thing is who got there first. A lead automatically means a better position. Vadym got ahead of me when he found out about my resignation behind my back—and now I’m forced to justify myself, and my obsession with that despicable beauty pageant begins to look not entirely unimpeachable (Could it be retaliation by a disgruntled employee perhaps, instead of simple righteous indignation?)—and he is looking at me like that Dnipropetrovsk nut, as if he knows something about me that’s so dirty I’ll never be clean again. As they say in American movies, anything you say or do can and will be held against you.

From this moment on, Vadym owes me nothing; the moral advantage is on his side. And all I’m left to do is applaud his brilliantly calculated timing—and prepare to hear what else he’s got in store for me: this is no longer my interview, I’m not the one asking questions, our roles have reversed.

“What are you thinking of doing next? Have anything in mind yet?”

“I don’t know, I haven’t thought about it.”

“You better start. The clock’s ticking. The reshuffling of the media market is in full swing, the cushiest gigs are up for grabs right now. Closer to the elections you’ll be looking at leftovers and rejects.”

“Somehow, I don’t feel compelled to get reshuffled to accommodate the elections.”

“What else do you want?” he asks, surprised. “An election cycle is an injection of money! Good money, Daryna. It’s like in the ocean where at different depths different currents begin to form, some stronger, some weaker. This is your chance to ride the one that’ll take you to the top. Later will be too late. And you, I’m sorry, won’t be getting any younger either.”

Knocking the last stool from under me. Bingo.

“So, do think about it. I, by the way, might be able to put someone with your experience to good use.”

So this is what we’ve taken our sweet time getting to. All this was mere exposition for the main plot, and the plot comes now—plain as nails: I am being bought. I am unemployed: naked and available. On the block.

And for some reason, I’m terrified. Inside, a sickening chill blasts just below my breasts—as if they have come for me. (Who? The human figures with wolf heads I imagined were behind the door of my bedroom when I was little, Goya’s monsters, mad paramedics, machine-gunners with dogs?) As if all my fears that until this instant had been scattered across my life like shadows on a sunny day rose at once and stood to their full height, leaned all together against an invisible divider and flipped my life to the other side—and now it seems there has never been anything in it, except these fears, not a glimmer of sunshine. Catacombs, dungeons. An artificially lit cave. (Someone will throw the switch now—and it will turn dark, and I’ll never find my way out of this darkness; I will remain here forever, for Vadym to do with as he pleases.)

“I mean that show of yours, about unknown heroes,” he says suavely. “Diogenes’ something…”

“Diogenes’ Lantern.”

“Oh yes, lantern. Was he the guy who went around with a lantern looking for a man? Not bad, only you got too clever there; you gotta keep it simple for the common folks. But the way you created those heroes out of nothing—that was awesome! Super professional work.”

“Thank you. Only I wasn’t making anything out of nothing. They were all amazing people—every person I ever made a show about.”

“Whatever. You know how to package a person—how to turn some Joe Schmo into a cult figure. You’ve got, as they say, the sales pitch. I still remember your show about that priest who keeps an orphanage and how those retarded kids call him Daddy…”

“Not retarded. There was only one kid with Down syndrome.”

(The boy with Down syndrome was already a grown, stout, wide-shouldered youth with the cognitive development of a two-year-old—he laughed, pushed to grab on to the shiny eye of the camera, and hooted, again and again, the same line from a VV song, “Spring comes! Spring comes! Spring comes!”—and somehow was not in the least bit repulsive to look at, made so, perhaps, by the presence of the priest who adored his charge with a real fatherly tenderness, as though he could see in him something invisible to the rest of us. “Let every thing that hath breath praise the Lord,” the priest said, and it came out sounding especially beautiful somehow, so that I, the sentimental cow that I am, got all teary-eyed: every creature born to this world has the right to live and be happy praising the Lord, and what ever made us think that some of us are better, and others are worse? And then I remember that Vadym has a son from his first marriage—from that woman who lost her mind, and he sent the boy to study in England: to an orphanage, one could say, only of a different kind, a five-star one. Whom does that boy call Daddy there?)

“And are you aware of the fact that later, when the local elections came around, three parties fought each other for that priest’s endorsement?”

“Can’t be! I’d never…”

“Exactly. You’d never. You made him a public figure, a moral authority. Who was he before you discovered him? Just another ragtag village priest, without voice or power. And then you made your show—and he’s a spiritual shepherd! Pilgrims from the whole region mob his church; bigwigs roll up in SUVs, bringing their children. We’ll do as Father says! And you say it wasn’t out of nothing!”

“You have a strange way of looking at things, Vadym. My role was not at all as critical as you see it.”

“Oh, stop it. Modesty, as a friend of mine says, is the shortest path to anonymity.” Vadym pauses to give me the opportunity to appreciate the joke and when he doesn’t get a reaction (my head’s humming like a power substation), winks at me: “And you were a star! And could remain one.”

“You want me to help you create heroes, is that it?”

He looks at me almost gratefully—did I save him from further verbal exertion?

“Precisely.”

Another pause. A kind of very slow approach—millimeter by millimeter, so as not to startle his prey, except that his breathing gets louder. (I heard a man breathe like this once, the two of us were in the same train compartment: I woke up in the middle of the night because he, breathing like a horse, was very carefully, so as not to wake me, pulling the covers off me before dashing back to his berth, the instant I, scared to death, stirred and mumbled something as if still half asleep.)

“A political project. Image focused. We’ll put together a strong team, with first-class foreign experts; you’ll love it. Naturally, they will all work behind the scenes. What’s needed is a public face, sort of like a press secretary. But it can’t be just a pretty face; it has to be someone who knows what they’re doing. Someone from inside the kitchen, so to speak.”

“And what will that kitchen be cooking?”

He nods in approval: we’ve finally gotten to the heart of the matter.

“This information cannot be made public yet. In the elections, besides the two main contenders—from the establishment and the opposition—there will be a number of technical candidates.”

“Meaning what?”

“What—the usual. Candidates who are there to divert votes from the front-runner.”

“From Yushchenko?!”

Now I really don’t understand anything. Isn’t Vadym a member of Yushchenko’s coalition?

“Give me a break, Daryna!” he cringes, and I shudder: it’s Vlada’s phrase, part of her vocabulary, that’s where he got it! “Yushchenko, while we’re on the subject, is also, you could say, a technical candidate. In a way…”

“What on earth are you talking about?”

“I am talking about the fact that things are much more complicated than they appear to you. Than what they look like from the outside. And even if Yushchenko wins, although that’s more than doubtful, his victory won’t be the end of the game that’s going on, you can be sure of that. Yushchenko got propelled to the top by a whole series of favorable circumstances, he’s always had luck; you might say he’s charmed.” At this last word, Vadym’s voice twangs with a barely audible note of envy, like the ding of chipped glass. “But there’s no corporation behind him. The ones backing him as a viable candidate today are all the disgruntled ones, the ones Kuchma left standing with nothing when he divvied up the property. And a coalition like that, as you can surely see yourself, cannot last. If Yushchenko does manage, by some miracle, to win, all hell will break loose—the ones who ride his coattails to parliament will waste no time wresting the steering wheel away from him.”

“And you decided not to wait until after the elections?”

Lord, my head hurts!

“And I,” Vadym doesn’t take offense, only swirls the cognac in his glass unnecessarily fast—with a short, slightly nervous circular motion. “I attempt to take a broader view. And to benefit from any outcome. And I would advise you to do the same. What does it ultimately matter if it’s Kuchma, or Yushchenko, or someone else, or the next guy? You can’t teach a pig to sing. Think about it, who are we, really? A former colony, with no statehood tradition of our own, knee-deep in shit. A transit zone. In the current global scheme of things, that’s our only asset: we are a country conveniently located for transit. And that’s where we can earn our commission—and trust me, it’s not pennies. The future outlook is not too shabby either, if one knows how to use one’s head.”

“What kind of outlook do we have if no one cleans up the shit?”

“You’re not paying attention,” he chides me. “I told you, the Yalta era is about to end. The balance of power in the world is changing; new players are coming to the stage… China, possibly India. And until the new trade balance shakes itself out, Russia and America will keep dragging us back and forth, like dogs in a tug-of-war. Neither will let go—the bone’s too big. We’ve always been a trading card in the big countries’ games anyway; it’s a function of our geography. Except that only a few of them in the past century realized that Ukraine is nothing less than critical for any serious political ambitions—Lenin knew this, and, by extension, Stalin. Today, the Russians understand this much better than the Americans. Europe’s not even worth mentioning—they’re off the field, and it’s not a given that they’ll ever get back on it, aside from falling into the Kremlin’s sphere of influence.”

“You’re kidding?”

“Not the least bit. Gazprom already owns a good half of Europe. They have Nord Stream lobbyists in every European government. Everyone, Daryna, loves money. Especially the big kind. Especially when the one paying it is someone you used to fear. That’s power. Money, you know, is not just banks—it’s also cell-phone service operators, and Internet providers. You see what I’m saying? As soon as those losers in the EU implement electronic ballots, you can write Europe off. Politically it’ll mean no more than some Kemerov region; they’ll have all their leaders chosen in Moscow. So the stakes are quite high, Daryna—it’s a big game. And in the scheme of this game, we are the testing ground for new management technologies. The ones that will determine the fate of the world in the new century. Try to see it that way.”

“So what, we are a kind of a shooting range? Like in World War II, and with Chernobyl? Your big players come play here, see what happens, and then bury us again—till the next time?”

“A range—that’s well put. Here’s to your health!” He holds up his snifter to let the cognac flash in the light. “You have a way with words. History’s secret range. Not bad at all, it’s got that something… I bought this book the other day, by a British guy, about Poland, a thick one.” He stretches his fingers, a pair of sausages, to show me. “It’s called God’s Playground. I liked that, too—I think that’s even more fitting for Ukraine than for Poland.”

“Then it shouldn’t be God’s. Should be the Devil’s. The Devil’s Playground.”

(Devil’s Playground, yes—where the best are the ones who perish. The ones who expose themselves, who stand up from the trenches. One can’t expose oneself on the Devil’s Playground—can’t step into the floodlight’s beam, unless one plays for the side that’s sitting in the bushes with the sniper’s rifle; on the Devil’s Playground, one can only make good if one lives the way Vadym says: get low and watch where the strongest current will run—and swim in it. You are a wise, wise man, Vadym, aren’t you; you’ve got it all figured out…)

“Why do you have to be so dramatic,” he mutters, and an absurd hope that he is simply drunk flares up in me—that he is just drunk, that’s it. Look at how much less cognac there is in the bottle; I didn’t even notice how he’d siphoned all that out. This may well be merely the ramblings of an intoxicated man. Damn it, why is my head crackling and hissing so much—like a cell phone with a weak signal! No, drunk he is not.

“Now, a range—that’s well put!” He sticks to his tune. “That’s exactly what it will be. Just you wait and see—there’ll be a whole bunch of interesting new tricks launched for the first time in these elections! Someday, they’ll write textbooks about it. Post-information era government technologies—that’s something! It’s like when they first split the atom. In the beginning, no one could see what possibilities that opened up either. This’ll be an interesting year for you and me, Daryna.” All of a sudden, he rubs his hands together with such a youthful, hungry lust for life, like a teenage boy after a swim that I, taken by surprise, miss my chance to react to his “you and me.”

“Let’s have a drink! Let’s drink, honey, let’s drink here, they won’t pour on the other side…. What’s that, why didn’t you finish your ice cream? Watching your girlish figure?”

“Drink to what, Vadym? To whose victory?”

“Ours, Daryna, ours! Let those Yankees and Ivans tussle all they want; our business is to make profits! The first round in this game went to Russia: after the Gongadze case, the Kremlin’s got Kuchma right where they want him, totally under their control. Now they’re betting on the Donets’k contingent, they do business together; they’re one crew and all that, I’m sure you know this. Going back to the Soviet days. And the Americans bet on Yushchenko—with the goal of keeping Ukraine in the buffer zone. And we shall wait and see how well it works for them.”

“And all the people who actually live in this country—the way you see it, they aren’t a part of this game? We’ve no will of our own?”

“Whose masses do, Daryna? Name one country. Or do you, by chance, believe that bullshit about history being shaped by the people? Don’t make me laugh; we don’t live in the nineteenth century! Seventy percent of people, according to statistics, wouldn’t know their own opinion if it bit them in the ass—they just keep repeating whatever they’ve heard. People are stupid, Daryna. That’s the way it has always been and always will be. People eat up what’s put before them. And you belong to the elite who have the opportunity to do the putting. So, please, do me a favor, don’t take that for granted.”

He squints—quickly, conspiratorially—and again this flicker, like a shadow across the surface of the water (and I’m underwater; I am under the whole time; what gills do I have to breathe?) and a flare-up of another senseless hope: what if it’s a sign he is giving me (Before whom, in front of what third party or surveillance camera?), a sign that all this is not for real, that he is pulling my leg and I shouldn’t believe a single word he says? “Do not trust anyone, and no one will betray you”—was it Vadym who said that? (When?) But instead, he grows more solemn.

“So when it comes to serious money, Daryna, only Russia is prepared to invest in us. That’s the reality.”

In my mind, I shake off the water—droplets sit cool under my skin.

“The foreign experts you mentioned—those are Russians?”

“What does that matter?” he shrugs. “I am offering you the most interesting work a creative person could have, and right up your alley: take a dark horse, Vasya the gas-station-guy, doesn’t matter who, we can talk about that later…. You take him—and make him a hero! A leader! A cult figure with his own myth—you guys can figure out what that myth is, brainstorm something together. You’re creating your own hero, like the Good Lord from clay—how beautiful is that? And in the people’s memory that Vasya will remain the man you made him. It’s like a whole new kind of art, right there! And with the widest appeal—even cinema can’t come close.”

You couldn’t say Vadym spent four years with an artist for nothing.

(Art, Vlada used to say, contemporary art, is first and foremost the making of one’s own territory, a discrete exhibition space where no matter what you brought in, even a urinal, would be perceived a work of art: modern civilization has allocated its artists a niche in which we can play with impunity, letting off steam, but from which we can no longer change anything in the accepted way of seeing things.)

“That’s not art, Vadym. Art is what you don’t get paid for.”

“Whoa there!” Vadym even leans back in his chair. “And when Leonardo da Vinci painted the Sistine Chapel—was he doing that for free now?”

“Michelangelo.”

“What?”

“Not Leonardo—it was Michelangelo. You’re getting it mixed up with The Da Vinci Code.”

“So Michelangelo, whatever. What’s the difference?”

“From the client’s point of view—none. The same job could have been done by someone else. They were only paying for a canonical treatment, nothing else. That airy lightness that blows you away, and you don’t even know why—that’s just a bonus, it may very well not have been there. Art is always a bonus. That’s how you know it when you see it.”

“Give me a break.” Vadym is visibly irritated by our detour off topic. “That was a different time, so of course the commissions were also different. The church is also a governing corporation, and, while we’re at it, it was the most powerful one of its time. Take a broader view, Daryna! Everyone does this, not just politicians—every person tries to create a legend out of their life, if only for their kids and grandkids. It’s just that not everyone can have this done professionally—that takes money…”

And another splash, and again I am underwater. Why didn’t it ever occur to me to see things the way he talks about them? Aidy’s professor at The Cupid, the old poetess who shook her dyed tresses before me so proudly—they are losers, amateurs who simply did not have any money, and so were trying to buy me with what they had: their thinning tresses, gossip, lies, the peeling gloss of worn-out fake reputations. And there was more, more—crowds of random faces spill out of my memory as if from the opened doors of an overstuffed closet: bosses of all kinds, administrators, directors, princes of tiny local fiefdoms, all performing their greeting rituals for me—television’s come!—in their offices. They click through my mind frame after frame like a newsreel from a military parade: the suits—gray, charcoal, black pinstripe, gray herringbone (one such bundle of tweed with suede elbow patches still calls me, keeps inviting me out to dinner)—rise energetically from behind their desks cluttered with telephones; a front-desk Mashenka brings in the coffee; and, after a short prelude, every one of them turns the conversation to his monumental contribution to one thing or another, blows himself up into a hot-air balloon, bigger and bigger, ready to fly up to the stratosphere, and stoops, and bows, and fawns over his goods. And then there were the high-fliers, the unacknowledged geniuses, the inventors of perpetual motion machines, and the victims of incredibly convoluted intrigues who couldn’t wait to fill my poor ears with assurances that their story was the one that was going to make me famous world over (the breed that, fortunately, has collectively diverted to cyberspace with the arrival of the Internet, like water finding a break in a dam).

Lord, how many of them, in my years of work on TV, danced around me like savages around an idol, with tambourines, hollering, flowers, and toasts—all to sway me to turn them into the fantasy heroes they wished to remain in people’s memories? Like electrons wrenched from their natural orbits by some tremendous explosion, all these people, even when they managed to find perfectly good places for themselves in this world, kept smoldering with the secret conviction that those places were not really theirs, and that they were really meant for a different, amazing and remarkable, life, which had either been taken away from them or was not yet apparent to everyone else—and that’s why they needed an apostle, an advocate, a sculptor with a mass-media chisel who would help bring out the contours of the masterpieces hidden in the shapeless bulk of their biographies, someone who would chisel away everything redundant, and reveal them to the awestruck and speechless world.

They’ve always been swarming around me, these wrenched-from-their-orbit electrons who dreamt of becoming simulacra. Only I used to treat their presence as an inevitable cost of doing business—like the dark side of the moon, a gloomy shadow that trails every vocation—this was just what you got for being a journalist, you couldn’t help it…. Now, when my own center of gravity has shifted, under Vadym’s assault, onto this other, dark side, I see for the first time, in close-up, the way the whole army of them, with Vadym at its helm, sees journalism; it turns out they weren’t the shadow at all—they were my profession itself, its essence, its bare and hard core, cleared of all extraneous layers: advertising.

Not information. Not the collection and dissemination of the information that helps people develop their own views, as I had believed until now. (To journalism students at the university, when they asked me what my gold standard of reporting was, I always said, watching their young faces turn puzzled and surprised, Chornovil’s underground Ukrainian Messenger, which he published in the 1970s—I can name no reporting more chemically pure than that.) But in fact, my shows are in the same class with commercial breaks: I am an advertiser; I advertise people. Others advertise beer and sanitary pads with wings, and I advertise people. Shape them into attractively packaged legends. That’s my specialty.

And that’s all there is to it, as Vadym says.

“Excuse me?”

“Twenty-five grand,” Vadym says. US dollars. A month. Until the end of the election campaign. And sits there looking at me, eyes narrowed. (What color are they?)

I must be really good at advertising people. I am also, it would appear, good at controlling my face before the camera: he doesn’t seem to be able to read anything from it.

Looks like he is a bit disappointed.

“Hotel California” is ending; I hear the last chords. My head is pounding so hard that muscles throughout my whole body reverberate with pain. And inside—it’s empty; the fear’s gone. It’s the strangest thing: I am taking this round—compared to the previous one, in my boss’s office—incomparably more calmly, as if it were all happening to someone else. The reactions I do experience are peculiarly physiological—pain, nausea; the emotional machinery seems unplugged, as if my body has taken on the entire burden of this conversation and I, myself, am playing no part in it. As in a dream.

Wait. What dream was like that?

The pause is getting long (a commercial break without content, the screen burns vacant, and someone’s money is going down the drain as the purchased airtime ticks on: TICK… TICK… TICK… TICK…).

“What do you say?” Vadym gives up. Gives up first. So I am stronger than he is. And Vlada intuited it correctly when she painted me a maiden warrior to the accompaniment of “The Show Must Go On”—she had the right instinct: to seek in me the fulcrum she needed to leverage this man up and free herself from under him. It’s too bad I proved such a coward back then, got scared, flailed, and clucked “I’m not like that!” I did not recognize, I couldn’t see. Could not see anything, stuck my head in the sand: I needed everything to be just fine in Vlada Matusevych’s life—for my own peace of mind. I, too, betrayed her; I’m as guilty as Vadym before Yushchenko. I ran. I deserted. I abandoned her.

What I’d most like to ask Vadym right now is whether he has seen those photos in her archive—the ones of the two of us, me in the witchy makeup, in the style of the early Buñuel heroines, Vlada with the bloody lipstick smeared across her mouth. But I won’t ask him this: even if he had found them, he wouldn’t have seen anything in them. And would not have understood anything.

So I ask something completely different—what he least expects to hear. “Why me, Vadym?”

And he looks away.

“Why did you choose me, of all people?”

(Softer, someone at my side seems to prompt—softer, more intimately, less steely…)

“Money like that could buy you any of the super-popular faces from the national channels,” I rumble low like a cello or a bandura, an intimate, chest-deep timbre (of course, the voice is key, folks knew it all the way back in the time of the fairytale in which the wolf runs to the smith, smithy-smithy, cast me a voice—how’s that not an electoral technology?). “My show’s not that popular, it wasn’t even in prime time, never made the top ten…”

“People trust you,” he answers simply. He has chosen to be sincere. Good move.

“Oh. I see. That’s nice to hear.”

A pause. TICK… TICK… TICK… TICK…

“And that’s it? That’s the only reason?”

“Well,” he smiles wide, his most charming smile yet, “that and then again—we’re family, aren’t we?”

We would be “family” if I agreed. That’s what he’s after—this is it, finally. We would, and the trafficking would vanish between us—delete, delete. Vlada would also disappear—the Vlada I remember. Vadym would’ve bought her from me, together with her death. The way he’s already bought her from her mother, and is now buying her from her child.

Now, this is really slick. Not just slick—it’s awesome, it’s brilliant, it’s all but enough to have me sitting here stunned, breathless, with my jaw dropped again: regardless of the ends a man’s intellect is pursuing, the sight of said intellect at work is always as irresistible to women as female beauty is to men. I applaud you, Vadym Grygorovych. What was it he said—“history is made by money”? It’s only logical that this should apply to the history of an individual life as well—all one needs is to choose his witnesses well. Buy the right witnesses, as in any decent lawsuit. Because every story is ninety-five percent about who does the telling. And he knows that I know this. And I know that he knows that I know…

For an instant, I short circuit, a spasm grips my throat, and I am blind with hatred for this self-satisfied face with its pink-lipped mouth lined with white ice-cream residue—but the hatred, too, is somehow not my own: I watch it inside me as though I were filming it. Somehow now I need to switch to his language—and I find I do speak it; I know how they talk, these people.

“I understand you, Vadym. Now look what we’ve got here. You say people trust me. If I agree, then after all these… interesting experiments of yours, one thing is certain—they won’t trust me any longer. Even if I commit ritual suicide, samurai-style, right on camera, people will say—eh, a publicity stunt. I won’t make any more heroes; I’ll have to retrain. You say profit. Fine, let’s do the math. Twenty-five grand a month, how long do we have before the elections—six months? Okay, let’s say seven. Twenty-five times seven—a hundred and seventy-five. You are proposing that I sell”—(And here I break pace for a second: sell what? My country, which foreign secret services aim to shove back into the hole it hasn’t been able to dig itself out of anyway, going on thirteen years already? My friend whose death is on my conscience too, and whose memory is now on my conscience alone? No, none of that will do)—“sell my professional reputation”—(there, that’s better)—“for one hundred and seventy-five thousand dollars? For the price of a one-bedroom apartment in Pechersk? That won’t cut it, Vadym. I did spend ten years earning it, you know. And you, as my father-in-law says, want to pay a penny for a handful of nickels.”