ACT ONE Daughter of Parihaka

CHAPTER TWO

Flux of War

1

This is not a history of the Taranaki Wars. After all, I’m only a retired teacher who obtained my qualifications from Ardmore Teachers’ Training College, Auckland, in the 1960s. I will there-fore leave it to you to read the accounts of university-trained historians on the subject.

When I was younger, my elders would often talk on the marae about what happened to Maori way back then, but I really wasn’t interested. I had a well-paid job, Pakeha friends — and a Pakeha girlfriend that Josie doesn’t know about. Although I copped the occasional Maori slur or racist remark — ‘Hori’ or ‘Blacky’, you know the sort of thing — I generally laughed it off. If it got a bit too out of hand, as in, ‘Hey, you black bastard, can’t you find a girlfriend among your own kind?’ I was handy with my fists. On the whole, however, Pakeha and Maori got along pretty well really.

I think my tau’eke and kuia were affronted that I was teaching our kids about the kings and queens of England when there was all our own Maori history around us. In my own defence, I guess it was easier for me to look somewhere else, where history belonged to the victor and happened to other people, rather than locally, where we were the vanquished and it was a bloody mess. ‘Why bring up all that old stuff?’ I’d say to my elders. ‘We’re all one people now.’

It took the 1970s, when Whina Cooper led the land march from Te Hapua at the top of the North Island all the way down the spine to Parliament in Wellington, for me to confront the fact of ‘that old stuff’ and that, actually, we weren’t one people at all: history’s fatal impact had also happened here, in my own land.

I joined the march because my Auntie Rose came around to pick me up, no buts or maybes. She said to Josie, ‘I’m borrowing my nephew for a while.’

Josie answered, ‘Good, don’t return him if you don’t want to.’

The protesters carried banners proclaiming Honour the Treaty and Not One More Acre of Maori Land; while some of the stuff they spouted was pretty offensive, there I was, right in the middle of it all, and it started to rub off on me. It wasn’t long before I looked around and realised: Hey, where was our land, here in the Taranaki? What had happened to us? My eyes were opened.

They stayed opened.

But this isn’t my story; it is Erenora’s.

I’ve done my best in telling it because, of course, Erenora wrote it originally in Maori. When the family gave me the task of translating the manuscript into English, I must say I found it daunting. A lot of her handwriting had faded, making it difficult to read. And some of her phrasing — well, I’ve had to explain it a bit for the modern reader. But I’ve tried to ensure at all times that it’s my ancestor’s voice, not mine, in the translation.

Better a family member to do the job than a stranger, eh?

2

‘Mine were not the only parents who were killed by the Niger’s shells. All of us who were orphans were taken in by other families at Warea. In my case a couple by the name of Huhana and Wiremu took a shine to me. Even so, I felt I owed it to Enoka and Miriam to remember them as long as I could. As old as I am now, I have never forgotten their a’ua, their appearance. I know they loved me.

‘Following the attack, I returned to the mission’s classroom, my Bible and my books. After all, I was a little Christian girl, somewhat serious, and although I was puzzled that my parents were dead, I knew they would be together in heaven. But I did begin to wonder why, when the Pakeha professed Christian love, they would fight on Sundays, destroy the very churches we worshipped in and burn our prayer books. And why did they want to take land they did not own?

‘There was also the matter of Rimene. He had left Warea before the Niger’s shelling, and some people even said that he had probably given the Crown details that enabled them to target the community. Although, under Te Whiti and Tohu’s guidance, we rebuilt Warea, especially the mill, the people were suspicious of him. Whose side was he really on? He made several attempts to convince us that he loved us but, clearly, the assault on Taranaki placed all missionaries in a difficult position: they were shepherds with Maori flocks, but their masters were Pakeha. This was why, I think, many Taranaki tribes turned against the missionaries and also rejected the baptismal English names that had been given them.

‘Notwithstanding the suspicions about what Rimene did, or might have done, I will always remember him for a particular kindness. He must have had a soft spot for me. On the last occasion I saw him, he gave me a gift, a book of German phrases, and he stroked my chin. “Leb wohl, mein Herz,” he said. “Go well, sweetheart.”

‘I never forgot the words or him. But when Rimene abandoned us, we had already learnt to fend for ourselves.’

3

The situation between Maori and Pakeha escalated to full-scale war, and the Pakeha soon discovered that the love of Taranaki iwi for the land was greater than their own desire to steal it.

In 1860 Maori fought battles at Puketakauere and Omukukaitari and faced bombardment at Orongomaihangi. In 1861 they faced off troops under Major-General Thomas Simson Pratt for almost three months as he advanced by a series of trenches and redoubts.

Facing strong Maori resistance, however, and the huge costs of maintaining his troops, in May 1863, Governor George Grey declared the abandonment of the Waitara purchase and renounced all claims to it. At the time, Grey was in control of all military operations in New Zealand; he was in his second term as governor.

The troops may have retreated from the Waitara but they appeared within weeks to occupy the Tataraimaka Block and were closing in on Warea again.

Erenora was seven years old by then, and Te Whiti and Tohu had stepped into the gap left by Rimene’s desertion and become the people’s leaders.

4

‘We had already faced bombardment three years earlier by the Niger. This time, under supporting naval fire from the Eclipse, forty of our warriors died at the outer trenches of our pa. They had been protecting the rest of us; as was our practice we were sheltering within.

‘Te Whiti and Tohu kept us at prayer in the darkness but I saw Huhana stealthily leave our huddled congregation. “Where are you going?” I asked her. She replied, weeping, “You stay here, Erenora. I have to see what has happened to my husband. If Wiremu is dead, I must find out what the soldiers have done with his body or where they have taken him.” Even though Huhana told me to remain, I followed her. When she saw me dogging her footsteps she said, “’aere atu, go back, you’ll only get in the way.” But I wouldn’t listen to her.

‘The bodies had been laid out in a long row in front of the trenches and rifle positions where they had fought. Two important-looking men came to inspect them. I didn’t know it at the time but I later found out that one of them was Governor Grey. He seemed like a king on his white horse; it was such a pretty horse, stepping lightly along the trenches as, from his saddle, Grey inspected the dead warriors. Then he nodded to the soldiers and left.

‘Poor Huhana was distraught when she saw Wiremu’s body being dumped into a pit with all the others; some of the warriors were still alive, and one arm appeared to reach up before the dirt covered it. Our hearts were thudding as we waited for the soldiers to leave. Some of the bluecoat sailors stayed to have a smoke; how I wished they would just go. But once they had departed, Huhana called to me, “Kia tere, Erenora, quickly!” We ran to the pit to dig the men up. From all around, other villagers, having ceased their praying, were also running to dig, dig and dig with their hands. Huhana began to wail loudly when she found Wiremu; she hugged him close to her chest.

‘Among those who were kua mate, gone, I saw a twelve-year-old boy; his was not the only young body among the warriors. I recognised him as the same one who, three years earlier, had soothed my fears. I had come to know him as Horitana and had grown accustomed to seeing him from the schoolroom window, sometimes waving to me as he worked in the potato plantations.’

Erenora cleared the earth from Horitana’s face. He was still and wan with the waxen pallor of death.

‘When we first met,’ she said to him, ‘my heart opened to your aro’a, your love, but now you are dead. And every now and then I have seen you watching me in Warea to see if I am all right. How will I live without you?’ She lowered her face to his and wept and wept.

All of a sudden, Horitana coughed dirt from his mouth … then more dirt. He was alive! He began to take deep breaths and, once he had recovered, looked into her eyes and smiled weakly. ‘God has saved me for some purpose,’ he said. ‘He took me down into death so that I would get the taste of the land in my mouth and, behold, I am resurrected. Now that I have savoured our sweet earth, I will always serve it.’

Erenora cried out to Huhana, ‘Kui! Help me!’

Other women hurried to her side. They lifted Horitana from the earth. ‘We must keep digging out our other men, Erenora,’ Huhana said. ‘You take Horitana to the stream and wash the dirt from him.’

Erenora led him away but, when they reached the waterway, Horitana was embarrassed. ‘No, I can wash myself,’ he said.

Afterwards, when he was huddled in blankets, Erenora sat with him as he ate bread and drank some water.

5

The following days were a blur of men digging graves for those who had died and women wailing at tangi’anga, the burial rites. In the aftermath, Horitana stayed with Huhana and Erenora, chopping wood, gathering potatoes and catching fish for the cooking fires of other villagers. Huhana may have hoped that, now that she was a widow, Horitana would stay and become as a son to her. Every now and then, however, she saw him looking at the faraway hills; she knew he was restless.

A few days later, Erenora saw Horitana talking to Huhana. Then he knelt before the old woman. ‘What’s going on?’ Erenora asked.

‘Horitana has asked my blessing,’ Huhana answered. ‘Maori chiefs are fighting to the south, and he wishes to join them.’

‘What about us?’ Erenora was panicking.

‘Erenora!’ Huhana reprimanded her. ‘We can look after ourselves.’ Ignoring the young girl, she began a prayer for Horitana’s safety.

At the end of the karakia, Horitana saw that Erenora was still disconsolate. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be back,’ he assured her.

That evening, he said his goodbyes to Te Whiti, Tohu and the villagers. He asked Erenora to walk with him to the perimeter of Warea. Although he was tall, he was still a boy and not yet a man.

They stood watching the moon, and then Horitana turned to Erenora with his shining eyes. ‘Will you wait for me?’ he asked.

Erenora was much too young even to know what he was talking about. She knew, however, that she couldn’t say no.

‘If you want me to,’ she answered.

She watched with sadness as he melted into the bush and headed north.

Not long after that, Te Whiti and Tohu decided to take leave of Warea. They called upon those who had always followed them, and any others who wished to join them, to trust in another journey.

‘When I brought you here from Waikanae,’ Te Whiti said, ‘I thought we would be safe. But we have already been attacked twice. What happens if the soldiers come again? We have lost enough of our people. It is time to leave.’

At his words, the followers began to weep. Abandon the village they loved? But Te Whiti was adamant. He had already begun to fashion a remarkable new fellowship in God, a Maori brotherhood of man. After all, while the beliefs taught him by Minarapa at Waikanae and Riemenschneider at Warea had been based on Christian brotherhood, the offer of true fellowship to Maori was often lacking. But did not Christ also love the Maori? If He did, better to interpret the Bible and its many promises to the Chosen People from a Maori, not Pakeha, point of view. Better to act for themselves.

‘We are the more’u,’ Te Whiti continued, ‘the survivors, and God will succour us as we continue our travels. Although we may die many times, we will rise again in the face of adversity. Let us leave Warea for another sanctuary, another haven, our own Canaan land. Therefore gather our belongings, our children and our livestock, all that we can carry.’

He led the people swiftly away, and their pilgrimage in the wilderness began.

‘Me ’aere tatou,’ he said. ‘Let us go.’

1

This is not a history of the Taranaki Wars. After all, I’m only a retired teacher who obtained my qualifications from Ardmore Teachers’ Training College, Auckland, in the 1960s. I will there-fore leave it to you to read the accounts of university-trained historians on the subject.

When I was younger, my elders would often talk on the marae about what happened to Maori way back then, but I really wasn’t interested. I had a well-paid job, Pakeha friends — and a Pakeha girlfriend that Josie doesn’t know about. Although I copped the occasional Maori slur or racist remark — ‘Hori’ or ‘Blacky’, you know the sort of thing — I generally laughed it off. If it got a bit too out of hand, as in, ‘Hey, you black bastard, can’t you find a girlfriend among your own kind?’ I was handy with my fists. On the whole, however, Pakeha and Maori got along pretty well really.

I think my tau’eke and kuia were affronted that I was teaching our kids about the kings and queens of England when there was all our own Maori history around us. In my own defence, I guess it was easier for me to look somewhere else, where history belonged to the victor and happened to other people, rather than locally, where we were the vanquished and it was a bloody mess. ‘Why bring up all that old stuff?’ I’d say to my elders. ‘We’re all one people now.’

It took the 1970s, when Whina Cooper led the land march from Te Hapua at the top of the North Island all the way down the spine to Parliament in Wellington, for me to confront the fact of ‘that old stuff’ and that, actually, we weren’t one people at all: history’s fatal impact had also happened here, in my own land.

I joined the march because my Auntie Rose came around to pick me up, no buts or maybes. She said to Josie, ‘I’m borrowing my nephew for a while.’

Josie answered, ‘Good, don’t return him if you don’t want to.’

The protesters carried banners proclaiming Honour the Treaty and Not One More Acre of Maori Land; while some of the stuff they spouted was pretty offensive, there I was, right in the middle of it all, and it started to rub off on me. It wasn’t long before I looked around and realised: Hey, where was our land, here in the Taranaki? What had happened to us? My eyes were opened.

They stayed opened.

But this isn’t my story; it is Erenora’s.

I’ve done my best in telling it because, of course, Erenora wrote it originally in Maori. When the family gave me the task of translating the manuscript into English, I must say I found it daunting. A lot of her handwriting had faded, making it difficult to read. And some of her phrasing — well, I’ve had to explain it a bit for the modern reader. But I’ve tried to ensure at all times that it’s my ancestor’s voice, not mine, in the translation.

Better a family member to do the job than a stranger, eh?

2

‘Mine were not the only parents who were killed by the Niger’s shells. All of us who were orphans were taken in by other families at Warea. In my case a couple by the name of Huhana and Wiremu took a shine to me. Even so, I felt I owed it to Enoka and Miriam to remember them as long as I could. As old as I am now, I have never forgotten their a’ua, their appearance. I know they loved me.

‘Following the attack, I returned to the mission’s classroom, my Bible and my books. After all, I was a little Christian girl, somewhat serious, and although I was puzzled that my parents were dead, I knew they would be together in heaven. But I did begin to wonder why, when the Pakeha professed Christian love, they would fight on Sundays, destroy the very churches we worshipped in and burn our prayer books. And why did they want to take land they did not own?

‘There was also the matter of Rimene. He had left Warea before the Niger’s shelling, and some people even said that he had probably given the Crown details that enabled them to target the community. Although, under Te Whiti and Tohu’s guidance, we rebuilt Warea, especially the mill, the people were suspicious of him. Whose side was he really on? He made several attempts to convince us that he loved us but, clearly, the assault on Taranaki placed all missionaries in a difficult position: they were shepherds with Maori flocks, but their masters were Pakeha. This was why, I think, many Taranaki tribes turned against the missionaries and also rejected the baptismal English names that had been given them.

‘Notwithstanding the suspicions about what Rimene did, or might have done, I will always remember him for a particular kindness. He must have had a soft spot for me. On the last occasion I saw him, he gave me a gift, a book of German phrases, and he stroked my chin. “Leb wohl, mein Herz,” he said. “Go well, sweetheart.”

‘I never forgot the words or him. But when Rimene abandoned us, we had already learnt to fend for ourselves.’

3

The situation between Maori and Pakeha escalated to full-scale war, and the Pakeha soon discovered that the love of Taranaki iwi for the land was greater than their own desire to steal it.

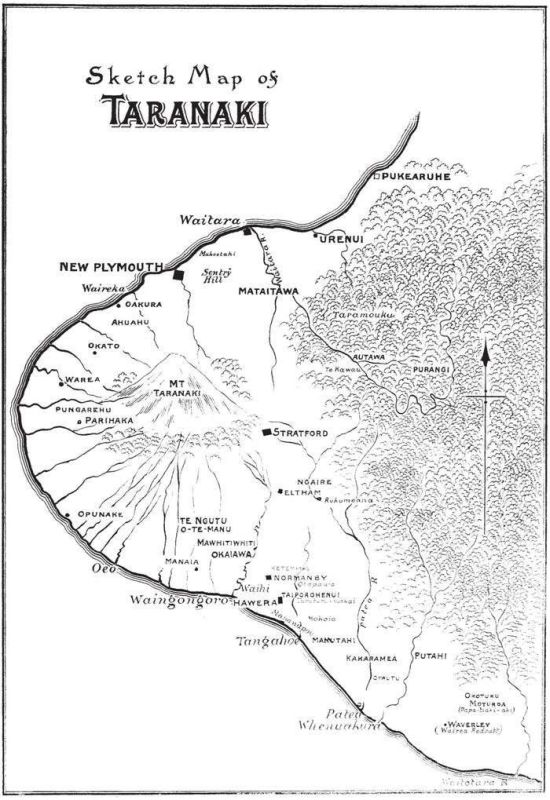

In 1860 Maori fought battles at Puketakauere and Omukukaitari and faced bombardment at Orongomaihangi. In 1861 they faced off troops under Major-General Thomas Simson Pratt for almost three months as he advanced by a series of trenches and redoubts.

Facing strong Maori resistance, however, and the huge costs of maintaining his troops, in May 1863, Governor George Grey declared the abandonment of the Waitara purchase and renounced all claims to it. At the time, Grey was in control of all military operations in New Zealand; he was in his second term as governor.

The troops may have retreated from the Waitara but they appeared within weeks to occupy the Tataraimaka Block and were closing in on Warea again.

Erenora was seven years old by then, and Te Whiti and Tohu had stepped into the gap left by Rimene’s desertion and become the people’s leaders.

4

‘We had already faced bombardment three years earlier by the Niger. This time, under supporting naval fire from the Eclipse, forty of our warriors died at the outer trenches of our pa. They had been protecting the rest of us; as was our practice we were sheltering within.

‘Te Whiti and Tohu kept us at prayer in the darkness but I saw Huhana stealthily leave our huddled congregation. “Where are you going?” I asked her. She replied, weeping, “You stay here, Erenora. I have to see what has happened to my husband. If Wiremu is dead, I must find out what the soldiers have done with his body or where they have taken him.” Even though Huhana told me to remain, I followed her. When she saw me dogging her footsteps she said, “’aere atu, go back, you’ll only get in the way.” But I wouldn’t listen to her.

‘The bodies had been laid out in a long row in front of the trenches and rifle positions where they had fought. Two important-looking men came to inspect them. I didn’t know it at the time but I later found out that one of them was Governor Grey. He seemed like a king on his white horse; it was such a pretty horse, stepping lightly along the trenches as, from his saddle, Grey inspected the dead warriors. Then he nodded to the soldiers and left.

‘Poor Huhana was distraught when she saw Wiremu’s body being dumped into a pit with all the others; some of the warriors were still alive, and one arm appeared to reach up before the dirt covered it. Our hearts were thudding as we waited for the soldiers to leave. Some of the bluecoat sailors stayed to have a smoke; how I wished they would just go. But once they had departed, Huhana called to me, “Kia tere, Erenora, quickly!” We ran to the pit to dig the men up. From all around, other villagers, having ceased their praying, were also running to dig, dig and dig with their hands. Huhana began to wail loudly when she found Wiremu; she hugged him close to her chest.

‘Among those who were kua mate, gone, I saw a twelve-year-old boy; his was not the only young body among the warriors. I recognised him as the same one who, three years earlier, had soothed my fears. I had come to know him as Horitana and had grown accustomed to seeing him from the schoolroom window, sometimes waving to me as he worked in the potato plantations.’

Erenora cleared the earth from Horitana’s face. He was still and wan with the waxen pallor of death.

‘When we first met,’ she said to him, ‘my heart opened to your aro’a, your love, but now you are dead. And every now and then I have seen you watching me in Warea to see if I am all right. How will I live without you?’ She lowered her face to his and wept and wept.

All of a sudden, Horitana coughed dirt from his mouth … then more dirt. He was alive! He began to take deep breaths and, once he had recovered, looked into her eyes and smiled weakly. ‘God has saved me for some purpose,’ he said. ‘He took me down into death so that I would get the taste of the land in my mouth and, behold, I am resurrected. Now that I have savoured our sweet earth, I will always serve it.’

Erenora cried out to Huhana, ‘Kui! Help me!’

Other women hurried to her side. They lifted Horitana from the earth. ‘We must keep digging out our other men, Erenora,’ Huhana said. ‘You take Horitana to the stream and wash the dirt from him.’

Erenora led him away but, when they reached the waterway, Horitana was embarrassed. ‘No, I can wash myself,’ he said.

Afterwards, when he was huddled in blankets, Erenora sat with him as he ate bread and drank some water.

5

The following days were a blur of men digging graves for those who had died and women wailing at tangi’anga, the burial rites. In the aftermath, Horitana stayed with Huhana and Erenora, chopping wood, gathering potatoes and catching fish for the cooking fires of other villagers. Huhana may have hoped that, now that she was a widow, Horitana would stay and become as a son to her. Every now and then, however, she saw him looking at the faraway hills; she knew he was restless.

A few days later, Erenora saw Horitana talking to Huhana. Then he knelt before the old woman. ‘What’s going on?’ Erenora asked.

‘Horitana has asked my blessing,’ Huhana answered. ‘Maori chiefs are fighting to the south, and he wishes to join them.’

‘What about us?’ Erenora was panicking.

‘Erenora!’ Huhana reprimanded her. ‘We can look after ourselves.’ Ignoring the young girl, she began a prayer for Horitana’s safety.

At the end of the karakia, Horitana saw that Erenora was still disconsolate. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be back,’ he assured her.

That evening, he said his goodbyes to Te Whiti, Tohu and the villagers. He asked Erenora to walk with him to the perimeter of Warea. Although he was tall, he was still a boy and not yet a man.

They stood watching the moon, and then Horitana turned to Erenora with his shining eyes. ‘Will you wait for me?’ he asked.

Erenora was much too young even to know what he was talking about. She knew, however, that she couldn’t say no.

‘If you want me to,’ she answered.

She watched with sadness as he melted into the bush and headed north.

Not long after that, Te Whiti and Tohu decided to take leave of Warea. They called upon those who had always followed them, and any others who wished to join them, to trust in another journey.

‘When I brought you here from Waikanae,’ Te Whiti said, ‘I thought we would be safe. But we have already been attacked twice. What happens if the soldiers come again? We have lost enough of our people. It is time to leave.’

At his words, the followers began to weep. Abandon the village they loved? But Te Whiti was adamant. He had already begun to fashion a remarkable new fellowship in God, a Maori brotherhood of man. After all, while the beliefs taught him by Minarapa at Waikanae and Riemenschneider at Warea had been based on Christian brotherhood, the offer of true fellowship to Maori was often lacking. But did not Christ also love the Maori? If He did, better to interpret the Bible and its many promises to the Chosen People from a Maori, not Pakeha, point of view. Better to act for themselves.

‘We are the more’u,’ Te Whiti continued, ‘the survivors, and God will succour us as we continue our travels. Although we may die many times, we will rise again in the face of adversity. Let us leave Warea for another sanctuary, another haven, our own Canaan land. Therefore gather our belongings, our children and our livestock, all that we can carry.’

He led the people swiftly away, and their pilgrimage in the wilderness began.

‘Me ’aere tatou,’ he said. ‘Let us go.’

CHAPTER THREE

Te Matauranga a te Pakeha

1

As for Horitana, he was soon in the midst of the fighting.

Like many young boys of the time, he was simply a foot soldier. His young mind scarcely comprehended the traumatic machinations of the Pakeha as they established their settler society in Aotearoa. All he knew was that, although he was only thirteen, he was needed in the fight against them.

Alas, the Maori throughout Aotearoa found themselves facing increasing odds: government forces, local militia and, propelling it all, more and more Pakeha wishing to settle in New Zealand. They also faced an arch manipulator in Governor Grey, who, with one piece of legislation, achieved two goals: punishing Maori for fighting against Pakeha; and obtaining more land for Pakeha settlement. Thus his New Zealand Settlements Act enabled him to confiscate land from Maori because they had rebelled against what he considered to be his legitimate government.

Here’s how historian Dick Scott describes what took place:

In 1863 all of Taranaki except the uninhabited hinterland was proclaimed a confiscation area. From Wanganui to the White Cliffs this involved a million acres and with that bonanza, fortune hunters, younger sons without prospects and Old World failures of all kinds need moulder no longer in the colonial dustbin to which they had been relegated.[1]

What else could Maori do except continue to defend the land?

We know from eyewitness accounts that Horitana fought with such defenders, led by Te Ua Haumene, the founder of the Pai Marire religion, at the battle of Kaitake Pa in 1864. Te Whiti and Tohu acknowledged Te Ua who, two years earlier, had been visited by the Angel Gabriel, bringing a message from God. The angel, whose Maori name was Tamarura, told Te Ua to battle the Pakeha and cast their yoke from the Maori people. Some say that Te Whiti and Tohu inherited the mantle of Te Ua as a cloak, which combined with theirs in creating Parihaka.

Let’s imagine Horitana running, with other boys — bearers — along the trenches: older warriors are firing at the government troops and calling urgently for more ammunition. The battle is not going well for the Pai Marire; the ground shakes with the sounds of exploding shells and gunfire.

Horitana is passing one warrior to supply another with bullets when the man slumps down, a bullet through his head. Horitana picks up the dead man’s tupara — his double-barrelled shotgun — loads and, sighting above the trench, fires. What are his thoughts as he watches a fresh-faced young soldier fall, his chest blossoming red?

The record shows that 420 redcoats and eighty military settlers, together with supporting bombardments and devastating artillery fire, finally triumphed over the Maori defenders. ‘Come, boy, time to go,’ one of the warriors tells Horitana. ‘You’ve earned the shotgun, bring it with you. Live to fight another day.’

Blooded in the battle, Horitana flees. On the way he stumbles over a dead warrior with a tattoo on his buttocks — a spiral rapa motif. Later it would catch the eye of one of the redcoats; sliced from the body it was made into a tobacco pouch.

Once, Horitana had been a boy. Now, before his time, he is a man. Fighting a desperate rearguard action through the enemy lines, he goes on to further guerrilla action against the Pakeha soldiers at Te Morere, Nukumaru and Kakaramea.

2

You know, a lot of people are unaware that at one time there were more British troops in New Zealand than in any other country in the world; that’s how great the odds were against Maori.

Michael King offers some details:

In 1863 Grey used the opportunity provided by the second outbreak of fighting in Taranaki to prise further troops from the British Government. By early 1864 he had as many as 20,000 men at his disposal — imperial troops, sailors, marines, two units of regular colonial troops (the Colonial Defence Force and the Forest Rangers), Auckland and Waikato militia (the latter to be rewarded with confiscated land after the fighting), some Waikato hapu loyal to the Crown and a larger number of Maori from Te Arawa.[2]

The Taranaki Military Settlers were also formed, in 1865. Many were recruited from Australia, attracted by the prospect that they would be settled on the land, once they had gained it.

Under the command of Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, an imperial field force of some 3,700 men descended in what we Maori call the murderous Te Karopotinga o Taranaki, the slaughtering of the people and the encirclement of Taranaki. Yes, 3,700.

Imagine Horitana again, now a fully fledged warrior. War had made a hardened killer of him. Whenever he pressed the trigger of the tupara, he no longer wondered about the soldier or settler caught in his sights.

As for the people of Warea, they were on the run, trusting completely in their two prophet leaders.

3

‘You want a description of Te Whiti?

‘Aue! Well, he was the son of Honi Kaakahi, a chief of Te Ati Awa. His mother, Rangikawa, also came from a rangatira line and was the daughter of a Taranaki chief. His height was similar to Horitana’s as an adult, so that must mean he was around 5' 10''. His forehead was narrow and his face was marked by piercing eyes. He had a strong build and his movements were always dynamic, agile and spirited. I can remember that one of his fingers was missing; I think he had an accident at the mill at Warea. In all his life he was humble and gentle and, you know, he lived as part of the people and not apart from them. His wife was Hikurangi, a lovely woman. Actually, it was her sister, Wairangi, who was the wife of Tohu Kaakahi. Although he was Te Whiti’s uncle, Tohu was only three years older than him.

‘Our patriarchs likened our situation to that of the descendants of Joseph, the same Hohepa of the Old Testament who was sold into Egypt by his brethren. In some respects Te Whiti and Tohu saw in Joseph’s story a parallel with what the Treaty of Waitangi had done: some “brothers” signed it and others, like Taranaki, did not. They were thus enslaved by Pharaoh without their consent but, just as Hohepa and his descendants had done, the two prophets and their followers kept strongly to the belief that, one day, would come their deliverance from the Pakeha.’

Te Whiti and Tohu took the more’u along the coast.

There were around 200 of them, a rag-tag bunch of pilgrims: old men — the young having gone to fight — women and children. Te Whiti and Tohu and some of the men scouted ahead, carrying the very few arms they possessed. The main party was in the middle, the old women on horses, but the others on foot pushing handcarts or shepherding a few milking cows, bullocks, horses, pigs and hens before them. The rest of the men brought up the rear.

They were spied by a gunship at sea, probably the Eclipse, which was still in the vicinity. Next moment there was a small puff of smoke from the ship and its first shell exploded close to them.

‘We are too exposed,’ Te Whiti yelled. ‘Quickly, strike inland.’ The sound of cavalry pursuit followed them as, crying with alarm, they ran into the bush and climbed to higher ground where the cavalry’s horses couldn’t go and where they wouldn’t be easy targets for rifle fire.

They were all exhausted by the time they came to Nga Kumikumi, where Te Whiti thought they would be safe from the dogs of war. There they raised a kainga. Well, it was more like a camp really, with the scouts patrolling the perimeter, ready to tell the people to go to ground whenever soldiers were nearby.

The more’u didn’t stay there very long. A small band of other Maori trying to flee a pincer movement of the field forces came across their camp, and it was clear to Te Whiti that the soldiers would not be far behind. ‘Time for us to move again,’ he said.

Huhana woke Erenora. ‘Quickly, rouse the tataraki’i.’ Women were helping the men on sentry duty, and Huhana had a rifle in her hands. ‘We must leave before dawn.’ Her eyes were full of fear.

The word tataraki’i referred to the many orphan children in their ranks. It was the word for the cicada, which rubbed its legs together and made a chirruping noise. The great chief Wiremu Kingi Te Matakatea was credited with the symbolism surrounding the tataraki’i. ‘Watch the cicada,’ he said, ‘which disappears into its hiding places during winter but reappears in the summer.’

The children were the embodiment of Matakatea’s concept, always reminding the people to look beyond their current troubles to when the sun comes out. There must have been about seventy tataraki’i in the pilgrim band.

As the more’u departed Nga Kumikumi, Erenora was given a special job: Huhana told her to take charge of the young ones. ‘If we are attacked,’ Huhana said, ‘take them into the bush, and don’t come out with them until everything is clear.’

Erenora nodded, and crept around the tataraki’i, waking them and warning them. ‘Not a sound, all right?’ She even cocked her head at the dogs. ‘That goes for you too! No barking from any of you either, you hear me?’

Those dogs were good; they obeyed her.

With smoke rising behind them as the cavalry torched the camp, the survivors embarked again on their pilgrimage. This time their convoy included horse-drawn wagons as well as bullock sleds. They set down their belongings at Waikoukou, where they made another kainga, another makeshift camp; this was in 1866. However, their cooking fires gave their position away and when they were attacked there — Major-General Trevor Chute had taken over from Lieutenant-General Cameron in this, the last campaign of the Imperial forces in New Zealand — the running battle through the bush forced them to leave the protective embrace of Mount Taranaki and move to the foothills beside the Waitotoroa Stream.

‘I have a half-brother, Taikomako, living on a block of land there,’ Te Whiti said. ‘He will take us in.’

Erenora never knew how they managed to get away. All she recalled was the pell-mell flight, the sound of rifle fire, and her shame about one incident: she was with other children, herding the bullocks, when two beasts took flight and there was no time to go back for them. The villagers had to keep on going because if they were caught, what would Major-General Chute do to them? Finally evading the troops, they burst out of the bush. Lungs burning, they flung themselves down to rest in an area sheltered by small hillocks. It was there that Te Whiti and Tohu walked among the people. They could see how tired and distressed everyone was.

Huhana asked them, ‘Will there ever be an end to our running?’

Te Whiti hesitated … and then he looked up at Mount Taranaki, arrowing into the sky, and posed the question to the mountain. The mounga began to shine, and it answered him.

The prophet raised his hand for the attention of the people. ‘Put down your weapons,’ he began. ‘From this time forward, we live without them.’

There was a murmur of anxiety, but the mountain nodded and blessed his words.

‘Enough is enough,’ Te Whiti continued. ‘We will run no longer.’ He bent down and took some earth in his hands. ‘In peace shall we settle here, for good and forever, and we will call our new kainga Parihaka.’

1

As for Horitana, he was soon in the midst of the fighting.

Like many young boys of the time, he was simply a foot soldier. His young mind scarcely comprehended the traumatic machinations of the Pakeha as they established their settler society in Aotearoa. All he knew was that, although he was only thirteen, he was needed in the fight against them.

Alas, the Maori throughout Aotearoa found themselves facing increasing odds: government forces, local militia and, propelling it all, more and more Pakeha wishing to settle in New Zealand. They also faced an arch manipulator in Governor Grey, who, with one piece of legislation, achieved two goals: punishing Maori for fighting against Pakeha; and obtaining more land for Pakeha settlement. Thus his New Zealand Settlements Act enabled him to confiscate land from Maori because they had rebelled against what he considered to be his legitimate government.

Here’s how historian Dick Scott describes what took place:

In 1863 all of Taranaki except the uninhabited hinterland was proclaimed a confiscation area. From Wanganui to the White Cliffs this involved a million acres and with that bonanza, fortune hunters, younger sons without prospects and Old World failures of all kinds need moulder no longer in the colonial dustbin to which they had been relegated.[1]

What else could Maori do except continue to defend the land?

We know from eyewitness accounts that Horitana fought with such defenders, led by Te Ua Haumene, the founder of the Pai Marire religion, at the battle of Kaitake Pa in 1864. Te Whiti and Tohu acknowledged Te Ua who, two years earlier, had been visited by the Angel Gabriel, bringing a message from God. The angel, whose Maori name was Tamarura, told Te Ua to battle the Pakeha and cast their yoke from the Maori people. Some say that Te Whiti and Tohu inherited the mantle of Te Ua as a cloak, which combined with theirs in creating Parihaka.

Let’s imagine Horitana running, with other boys — bearers — along the trenches: older warriors are firing at the government troops and calling urgently for more ammunition. The battle is not going well for the Pai Marire; the ground shakes with the sounds of exploding shells and gunfire.

Horitana is passing one warrior to supply another with bullets when the man slumps down, a bullet through his head. Horitana picks up the dead man’s tupara — his double-barrelled shotgun — loads and, sighting above the trench, fires. What are his thoughts as he watches a fresh-faced young soldier fall, his chest blossoming red?

The record shows that 420 redcoats and eighty military settlers, together with supporting bombardments and devastating artillery fire, finally triumphed over the Maori defenders. ‘Come, boy, time to go,’ one of the warriors tells Horitana. ‘You’ve earned the shotgun, bring it with you. Live to fight another day.’

Blooded in the battle, Horitana flees. On the way he stumbles over a dead warrior with a tattoo on his buttocks — a spiral rapa motif. Later it would catch the eye of one of the redcoats; sliced from the body it was made into a tobacco pouch.

Once, Horitana had been a boy. Now, before his time, he is a man. Fighting a desperate rearguard action through the enemy lines, he goes on to further guerrilla action against the Pakeha soldiers at Te Morere, Nukumaru and Kakaramea.

2

You know, a lot of people are unaware that at one time there were more British troops in New Zealand than in any other country in the world; that’s how great the odds were against Maori.

Michael King offers some details:

In 1863 Grey used the opportunity provided by the second outbreak of fighting in Taranaki to prise further troops from the British Government. By early 1864 he had as many as 20,000 men at his disposal — imperial troops, sailors, marines, two units of regular colonial troops (the Colonial Defence Force and the Forest Rangers), Auckland and Waikato militia (the latter to be rewarded with confiscated land after the fighting), some Waikato hapu loyal to the Crown and a larger number of Maori from Te Arawa.[2]

The Taranaki Military Settlers were also formed, in 1865. Many were recruited from Australia, attracted by the prospect that they would be settled on the land, once they had gained it.

Under the command of Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, an imperial field force of some 3,700 men descended in what we Maori call the murderous Te Karopotinga o Taranaki, the slaughtering of the people and the encirclement of Taranaki. Yes, 3,700.

Imagine Horitana again, now a fully fledged warrior. War had made a hardened killer of him. Whenever he pressed the trigger of the tupara, he no longer wondered about the soldier or settler caught in his sights.

As for the people of Warea, they were on the run, trusting completely in their two prophet leaders.

3

‘You want a description of Te Whiti?

‘Aue! Well, he was the son of Honi Kaakahi, a chief of Te Ati Awa. His mother, Rangikawa, also came from a rangatira line and was the daughter of a Taranaki chief. His height was similar to Horitana’s as an adult, so that must mean he was around 5' 10''. His forehead was narrow and his face was marked by piercing eyes. He had a strong build and his movements were always dynamic, agile and spirited. I can remember that one of his fingers was missing; I think he had an accident at the mill at Warea. In all his life he was humble and gentle and, you know, he lived as part of the people and not apart from them. His wife was Hikurangi, a lovely woman. Actually, it was her sister, Wairangi, who was the wife of Tohu Kaakahi. Although he was Te Whiti’s uncle, Tohu was only three years older than him.

‘Our patriarchs likened our situation to that of the descendants of Joseph, the same Hohepa of the Old Testament who was sold into Egypt by his brethren. In some respects Te Whiti and Tohu saw in Joseph’s story a parallel with what the Treaty of Waitangi had done: some “brothers” signed it and others, like Taranaki, did not. They were thus enslaved by Pharaoh without their consent but, just as Hohepa and his descendants had done, the two prophets and their followers kept strongly to the belief that, one day, would come their deliverance from the Pakeha.’

Te Whiti and Tohu took the more’u along the coast.

There were around 200 of them, a rag-tag bunch of pilgrims: old men — the young having gone to fight — women and children. Te Whiti and Tohu and some of the men scouted ahead, carrying the very few arms they possessed. The main party was in the middle, the old women on horses, but the others on foot pushing handcarts or shepherding a few milking cows, bullocks, horses, pigs and hens before them. The rest of the men brought up the rear.

They were spied by a gunship at sea, probably the Eclipse, which was still in the vicinity. Next moment there was a small puff of smoke from the ship and its first shell exploded close to them.

‘We are too exposed,’ Te Whiti yelled. ‘Quickly, strike inland.’ The sound of cavalry pursuit followed them as, crying with alarm, they ran into the bush and climbed to higher ground where the cavalry’s horses couldn’t go and where they wouldn’t be easy targets for rifle fire.

They were all exhausted by the time they came to Nga Kumikumi, where Te Whiti thought they would be safe from the dogs of war. There they raised a kainga. Well, it was more like a camp really, with the scouts patrolling the perimeter, ready to tell the people to go to ground whenever soldiers were nearby.

The more’u didn’t stay there very long. A small band of other Maori trying to flee a pincer movement of the field forces came across their camp, and it was clear to Te Whiti that the soldiers would not be far behind. ‘Time for us to move again,’ he said.

Huhana woke Erenora. ‘Quickly, rouse the tataraki’i.’ Women were helping the men on sentry duty, and Huhana had a rifle in her hands. ‘We must leave before dawn.’ Her eyes were full of fear.

The word tataraki’i referred to the many orphan children in their ranks. It was the word for the cicada, which rubbed its legs together and made a chirruping noise. The great chief Wiremu Kingi Te Matakatea was credited with the symbolism surrounding the tataraki’i. ‘Watch the cicada,’ he said, ‘which disappears into its hiding places during winter but reappears in the summer.’

The children were the embodiment of Matakatea’s concept, always reminding the people to look beyond their current troubles to when the sun comes out. There must have been about seventy tataraki’i in the pilgrim band.

As the more’u departed Nga Kumikumi, Erenora was given a special job: Huhana told her to take charge of the young ones. ‘If we are attacked,’ Huhana said, ‘take them into the bush, and don’t come out with them until everything is clear.’

Erenora nodded, and crept around the tataraki’i, waking them and warning them. ‘Not a sound, all right?’ She even cocked her head at the dogs. ‘That goes for you too! No barking from any of you either, you hear me?’

Those dogs were good; they obeyed her.

With smoke rising behind them as the cavalry torched the camp, the survivors embarked again on their pilgrimage. This time their convoy included horse-drawn wagons as well as bullock sleds. They set down their belongings at Waikoukou, where they made another kainga, another makeshift camp; this was in 1866. However, their cooking fires gave their position away and when they were attacked there — Major-General Trevor Chute had taken over from Lieutenant-General Cameron in this, the last campaign of the Imperial forces in New Zealand — the running battle through the bush forced them to leave the protective embrace of Mount Taranaki and move to the foothills beside the Waitotoroa Stream.

‘I have a half-brother, Taikomako, living on a block of land there,’ Te Whiti said. ‘He will take us in.’

Erenora never knew how they managed to get away. All she recalled was the pell-mell flight, the sound of rifle fire, and her shame about one incident: she was with other children, herding the bullocks, when two beasts took flight and there was no time to go back for them. The villagers had to keep on going because if they were caught, what would Major-General Chute do to them? Finally evading the troops, they burst out of the bush. Lungs burning, they flung themselves down to rest in an area sheltered by small hillocks. It was there that Te Whiti and Tohu walked among the people. They could see how tired and distressed everyone was.

Huhana asked them, ‘Will there ever be an end to our running?’

Te Whiti hesitated … and then he looked up at Mount Taranaki, arrowing into the sky, and posed the question to the mountain. The mounga began to shine, and it answered him.

The prophet raised his hand for the attention of the people. ‘Put down your weapons,’ he began. ‘From this time forward, we live without them.’

There was a murmur of anxiety, but the mountain nodded and blessed his words.

‘Enough is enough,’ Te Whiti continued. ‘We will run no longer.’ He bent down and took some earth in his hands. ‘In peace shall we settle here, for good and forever, and we will call our new kainga Parihaka.’

CHAPTER FOUR

Oh, Clouds Unfold

1

By musket, sword and cannon, Major-General Chute cut a murderous swathe from Whanganui to the Taranaki Bight.

Just in case he missed Maori standing in his path — whether or not they were warriors or civilians didn’t matter — he smote them down when he turned back to Whanganui. He destroyed seven pa and twenty-one kainga. He also burned crops and slaughtered livestock; if he couldn’t kill Maori, he would starve them to death. ‘There were no prisoners made in these late engagements,’ the Nelson Examiner reported, somewhat chillingly, ‘as General Chute … does not care to encumber himself with such costly luxuries.’

Astonishingly, although the Angel of Death flew over Taranaki, Parihaka escaped in what some people called the Passover. Instead, as the trumpets and bugles of war faded, a sanctuary was born beneath unfolding clouds and, with the mountain looking on, the pilgrims built a citadel.

2

‘It was winter and bitterly cold, the wind coming off the flanks of Taranaki, when our prophets put an end to our pilgrimage. The peak was wearing a coronet of snow and the landscape all around was fringed with ice and snow drifts.

‘In the beginning, the only cover to be had from the driving rain was provided by the bullocks. The old people herded them to form a circle and then commanded them to lie down. Then they said to us, “Tataraki’i, huddle close to our beloved companions.” Oh, I will never forget the heat coming from those noble animals as they pillowed our heads and blew their steaming warmth over us.

‘When the weather was really stormy, the adults had to provide extra shelter by standing and becoming the roofs above us; they were like sentinels, and they sang to each other to keep themselves awake until the storm passed. Why did they do that? Well, as Huhana told me one morning, “Our children are our future. Without you, why keep going?”

‘Eventually we erected makeshift tents like the camp we had at Nga Kumikumi, but we couldn’t start raising our kainga quite yet, oh no. From my recollection it was 1867 and the spring tides, nga tai o Makiri, were especially high and strong. At those times when the moon switched from full to new, our people gathered kai moana, our staple diet. You can’t tell the spring tides, “Wait, we’re not ready!” or the fish to stop rising at the most propitious time of all for fishing! We were soon busy harvesting both shellfish and sea fish, like shark, and also trapping eels when they swirled upwards to suck at the surface of the water.

‘At the same time as this was happening, Te Whiti and Tohu were also concerned to get some seeds into the ground. If we missed the planting time, there would be no food in the coming year. Not until we had some cultivations under way were the two prophets satisfied. “Now we raise Parihaka,” Te Whiti said. And so we began the work of clearing the site. We were so happy to start building the kainga. Even the tataraki’i, how they chirruped!

‘Meanwhile, Huhana had fully taken me to her breast as my mother. She also took in two other orphans, Ripeka and Meri, as w’angai or adopted daughters. She said to Te Whiti, “If I have to take in one it might as well be three”, which was her way of saying that she had an embrace that could accommodate us all.

‘I can remember only hard-working but happy times through that warming weather. Ripeka and Meri and I helped the adults smooth down the earth and take the stones away so that the houses could be built. Ripeka was the pretty one, with her lovely face and shapely limbs. As for Meri, she always tried to please, and that endeared her to everyone.

‘Both my sisters were older than me but somehow they were followers rather than leaders. For instance, we had a small sled on which Ripeka and Meri would pile the stones, but I was the one who pulled the sled from the construction sites. Even in those days, although I was always slim, I was strong. Ripeka would follow my instructions but Meri was often disobedient. One time she thought she would give me a rest and pull the sled while I wasn’t looking, but she took it to the wrong place and unloaded it there. “I was only trying to help,” she said to me plaintively as I reloaded the sled. “Please, Meri, don’t try,” I answered.

‘It took us the best part of the season and then the summer to raise Parihaka. I think one of the reasons why it happened so quickly was that Te Whiti discouraged the carving of meeting houses or any such adornment on other w’are. He was more concerned with us concentrating on food-gathering and sustaining ourselves. He also wanted to discourage any competition between the various tribal peoples who came to live with us.

‘The days turned hot, and we sweated under the burning sun. Te Whiti ordered the men to build the houses in rows and very close together. Those men were out day and night selecting good trees to cut down for all the w’are. They sawed the trunks into slabs of wood, two-handed saws they used in those days, one man at each end. When a w’are’s roof was raised, we would cheer, sing and dance in celebration!

‘My sisters and I graduated to helping the women thatch the roofs with raupo, which the men brought from the bush. Huhana was always yelling to me, “Erenora, hop onto the roof.” Men mostly did the thatching but, sometimes, they were busy on other heavier work — and Huhana knew I had good balance and was not afraid of heights. The women threw the thatch up to me and I laid it in place. After that, my sisters and I helped the women as they made the tukutuku panels for the walls of the houses: I sat on one side pushing the reeds through the panels to my sisters on the other side; they would push the reeds back and, of course, Meri’s reed kept coming through at the wrong place. Why was she so hopeless?

‘Everybody was vigorous with the work. Later, my sisters helped to make blankets, pillows and clothing, but I had no patience with such feminine tasks and preferred to work outside with the men. Te Whiti and Tohu had marked out the surrounding country for cultivations and there were a lot of fences to construct, and small roadways and pathways between them. As we worked, we sang to each other and praised God for bringing us here. There could have been no better place really. The Waitotoroa Stream was ideal as a water supply, and it would have been almost impossible to sustain ourselves without it.’

‘It must have been around this time, as autumn descended and the leaves began to fall, that Te Whiti had word from the South Island that the Reverend Johann Riemenschneider had died. Apparently, after he and his wife had left Warea in 1860, Rimene had spent two years in Nelson. Then he accepted an invitation from a society in Dunedin to do mission work among the Maori people in the city. He lived four years there, and his body was committed to the earth in Port Chalmers.

‘Te Whiti mourned the German missionary, telling us, “Rimene did not achieve great victories but he sowed the seed of God so that the harvest was sure. What more can you ask from a servant of Christ?”

‘We all said a prayer for him. Now he was forever with the Lord. And I found my own karakia for him from the German phrasebook:

‘“Selig sind die Toten. Blessed are the dead.”’

3

The next few years flew by. Sometimes when Erenora looked back on them, it was as if the raising of Parihaka, so that it would stand triumphant in the sun, had taken place on one long day. Of course it hadn’t, but certainly Parihaka grew as Maori fled from the British soldiers in Taranaki.

‘From 200 people we increased to 500. Word got around, you see, that Te Whiti and Tohu were building a city, a kainga like the Biblical city of Jerusalem. We therefore mushroomed to over 1,000 as refugees poured in, driven by the encirclement of Taranaki. They were all hungry and thirsty, and some were grievously wounded. Once they had been fed and recovered, however, they had to pitch in straight away — no mucking around and having a rest! The consequence was that we were building all the time, and Parihaka was quickly forced to become a large kainga.

‘Still the refugees sought us out. Sometimes we would see a cloud of dust and know they were painfully making their way to salvation. Or the rain would part like a curtain and there they were, ghost-thin, crying out to us from the space between. At night, we lit a bonfire so that the flames would show those who were searching for us. During the day, a pillar of smoke, like the sword of an angel, revealed the gateway to Eden:

‘“Here be Parihaka.”

‘And when the pilgrims arrived, nobody was turned away.’

‘Depending on our skills, Te Whiti organised the iwi into working groups to ensure a continuous food supply. Farmers tilled the cultivations mainly of potato, pumpkin, maize and taro to the north and between us and the sea. The sea, of course, remained the source of our primary sustenance; whenever nga tai o Makiri came, down we would go to harvest the kai moana as it rose to the surface of the sea. Some men even ventured in waka out to the deep water to fish, but usually we kept close to shore. You could drown so easily in those dangerous seas; the weather could change even as you were watching it.

‘At the beginning Te Whiti didn’t like us to eat meat but, rather, to use our oxen and cattle as our beasts of burden. He wanted us to be self-sufficient but later we began to run sheep, pigs and poultry.’

‘One day the villagers were all busy storing kumara and kamokamo carefully away for the winter. Huhana happened to notice that some tataraki’i, bored with helping us, were baiting each other. She gave me a shrewd look and said, “Erenora, the children have stopped chirruping and are pulling each other’s wings off. Go and teach them something.”

‘I was astonished! After all, I must have been only eleven. Te Whiti was passing by and he said, “Yes, you go, Erenora. Plenty of others can store food but not many have your brains.” My sisters were affronted by Huhana’s remark that I was “too clever” and even more by Te Whiti’s acknowledgement of it. They were practising a poi dance, their poi going tap tap tap, tap tap tap. Ripeka sniffed and said, “You may have the brains but we have the beauty.” And Meri said, “I can do anything that Erenora can do,” which was true, but she always did it wrong.

‘Now, about Te Whiti, don’t forget that he himself was not without Pakeha education and knew the value of such learning. He was a scholar, had been a church acolyte at Waikanae and Warea; later he became a teacher, and he even managed the flour mill. Both he and Tohu were good organisers too. As Parihaka grew even larger, they were the ones who promulgated the regulations every person had to comply with; we all knew our civic duties. As well, they organised the daily and weekly timetables by which we conducted our work.’

‘Parihaka continued to grow and I grew up with it, leaving childhood behind. Apart from farm, forest and fishing teams we also had village officials, kitchen workers and maintenance staff. Teams regularly swept the pathways, collected the rubbish every day, kept the drains clear and cleaned the latrines. We still had scouts patrolling our perimeters but, now, we also had our own police! They were on duty day and night ensuring law and order. You don’t think that Parihaka became a great citadel by accident, do you?

‘I was so proud of Huhana. She was appointed the kai karanga, the strong-voiced woman, who would call us all awake before first light. She would call again at the end of the day to finish our labours.

‘Meanwhile, the refugees always brought news of what was happening in the rest of Taranaki. One of them sought me out.

‘“Are you Erenora? I have a message for you from Horitana.”

‘My heart skipped a beat. “How is he?”

‘“He is alive and still fighting,” was the answer.

‘“Where is he?” I asked.

‘“He is now defending the land with Titokowaru’s guerrilla army.”’

4

Ah, Titokowaru.

All you have to do is mention the name and Maori throughout Aotearoa will recognise it as belonging to one of the greatest warrior prophets our world has ever known. He was perhaps seven or eight years older than Te Whiti and, like him, as a young man had become a Christian of the Methodist persuasion. The four prophets — Te Whiti, Tohu, Titokowaru and Te Ua Haumene — created an astounding Old Testament framework for Maori in Taranaki.

Titokowaru’s warrior ways began when, along with everyone else, he took up the fight against the Pakeha’s continuing predations upon our land. Under military provocation, he led a raiding party near New Plymouth in protest. From that time onward, he became a dreaded presence, waging an increasing number of attacks against the Pakeha in the lands south-west of Parihaka.

You can’t pinpoint Titokowaru. He was both civilised and savage, peacemaker and rebel. He bestrode both the spiritual and temporal worlds. He was a man about whom Maori wove legends, but he was not invincible. At his army’s assault on Sentry Hill in April 1864, a Pakeha bullet took the sight from the old leader’s right eye. It was Horitana who, along with Titokowaru’s lieutenants, treated the wound. From that moment, the young man became like a favoured son to the great chief.

While Te Whiti was raising Parihaka, Titokowaru was rebuilding Te Ngutu-o-te-manu, just north of the Waingongoro River. Sixty houses were centred on an imposing marae in front of the awe-inspiring meeting house called Wharekura. Like Te Whiti, Titokowaru wanted to live in peace. The trouble was that his lands, too, continued to be encroached upon by Pakeha and, in 1868, his defining moment arrived.

And all his previous military actions paled against what was to come: the campaign known in history as Titokowaru’s War.

For two years, Pakeha New Zealand trembled before Titokowaru’s military genius and brilliance. The narrative of his army’s astonishing field tactics, fought with a blend of intelligence and savagery, makes the hair stand on end; and Horitana fought with him in five do-or-die campaigns.

Historian James Belich describes the encounters in this way:

At the outset, the odds against Titokowaru were immense, twelve to one in fighting men, and the chances of victory minuscule. Yet Titokowaru and his people destroyed one colonist army (at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu on 7 September 1868); comprehensively defeated another (at Moturoa on 7 November 1868); and scored several lesser victories (including Turuturumokai on 12 June 1868, and Te Karaka and Otautu on 3 February and 13 March 1869). Their least successful tactical performance was a drawn out battle at Te Ngutu-ote-manu on 21 August 1868, and it could be argued that even this was a strategic success.[3]

Belich goes on to point out that at Turuturumokai, on 7 September 1868, Titokowaru deployed his fearless lieutenants against the best that the Pakeha military could offer; it was at this same battle that the great Prussian general, Gustavus von Tempsky, fell.

What a life von Tempsky had lived. Adventurer, artist and newspaper correspondent, he had fought twice in Central America, mined gold in California and Australia and, in New Zealand, his name was attached to the Forest Rangers. So great was his mana that when he was killed both Pakeha and Maori honoured him.

Titokowaru’s victories ‘brought the colony to its knees’, Belich says. However, inexplicably, the tide turned against the warrior prophet. At Tauranga-ika he built a fortress — but his own army abandoned it before any attack by colonial troops. Some people say that he fell out of favour with whatever gods supported him; as easily offended as any of the Greek deities of Olympus, they lightly tapped his knees and his stride began to falter. What was the reason? Nobody knows. But soon, with £1,000 on his head, Titokowaru was on the run. His followers melted away from him and by the time he returned to his homelands in 1871, he was a different man. He was older and less turbulent in his ways. With his own dream fading, he established a close liaison with Te Whiti and Tohu and their dreams at Parihaka.

Meantime, Parihaka had, indeed, become a sanctuary. And Erenora was a young woman now, certainly no longer a girl.

5

‘As young as I was, I had become a good teacher. I loved the children and enjoyed teaching them the English language, knowing it would enable them to converse with Pakeha and understand European ways.

‘My greatest thrill, however, was taking time off from my teaching duties to help the men break in the bullocks so that they would accept the yoke of the plough and pull the scythe cleanly through the dirt. With so much acreage to plough, the village needed good teams of strong, obedient beasts and, for some reason, I was able to calm their fears. I would stroke them, saying, “Thank you for being our beloved companions on our journey through the vale of the world. Will you not continue to be partners with us as we go further together?” Then I would introduce them to the yoke and command them, “Pull now.”

‘Huhana wasn’t too sure how to take my masculine habits. “Oh, Erenora!” she would sigh, “I don’t know what to make of you! And if I feel this way, you must be a puzzle to the young men too!” I think that was why she began to get a bit more persistent in pushing me, and, to a lesser extent, Ripeka and Meri, towards attachments with suitable male candidates. “We need men in our family,” she would chastise me, “and babies for the future.”

‘My sisters were not backward in taking up our mother’s prodding, especially Ripeka, who loved flirting. I might not have been as pretty as them but I wasn’t without suitors. None of the boys, however, like one called Te Whao, were at all desirable to me — and some of them couldn’t even plough a straight line.’

Then, in the summer of 1873, when Erenora was seventeen, while she and her sisters were carrying calabashes of water from the stream they heard someone coming towards them. As the stranger drew nearer, they saw that it was a young man. Around him a few excited tataraki’i were buzzing.

He happened upon Ripeka first, no doubt because she had seen him approaching and wanted to flirt accidentally on purpose. But she wasn’t fast enough in pretending to slip and fall at his feet because Erenora felt his shadow cutting the sunlight across her path. One moment the sun had been hot and spinning, the next, Erenora was shivering, not because of the sudden eclipse of the light but because she knew her destiny had arrived.

‘May I have some of the cool, sweet water that you carry from the stream?’ the young man asked.

Erenora could not look up at first; she knew immediately that the stranger was Horitana, and her heart leapt because he was still alive and had finally returned home. Thank goodness, as he had a price on his head for fighting with Titokowaru. However, when she appraised Horitana her heart sank. Although there was some sadness about him, he still had his shining eyes and he was so handsome now, and, well, her sisters had always been the attractive ones — surely he’d be more interested in them. His hair was thick, long and matted, and he looked as if he’d been walking for years. Across his back was a haversack and slung in a pouch across his chest was an Enfield rifle; it was a sharpshooter’s weapon, now his favoured gun, which he had looted from a dead British soldier.

Heartsick, she nodded. ‘Yes, you may have some water.’ She didn’t even bother to try to push her hair back or wipe the sweat from her brow. What would be the use? She gave him the dried pumpkin shell.

The tataraki’i pressed closer, wanting to look at Horitana’s rifle. ‘’aere atu,’ Erenora said to them. She began to motion them away and would have followed except that Horitana reached out a hand and stopped her.

‘No, don’t go,’ he said. Despite his war-weary appearance, he was attentive and polite. ‘It would be even nicer if your lovely hands would tip the calabash so that the sweet water can pour between my waiting and eager lips.’ His voice was low, thrilling and slightly teasing.

Erenora had never liked being addressed in such a familiar manner, so she said petulantly, ‘I do no man’s bidding! Tip the shell yourself or ask one of the other women to do it for you!’ Ripeka would have loved to do that.

Horitana didn’t take offence. Instead he laughed, ‘Don’t be angry with me.’ In a softer tone he said, ‘I haven’t had the opportunity in my life to know what is appropriate to say to women, and what is not.’

Erenora gave him a look of acceptance. She watched as he lifted his face, opened his mouth and held the calabash above it. Some of the water splashed down his neck. If he only knew how she wanted to lick the water. And the masculine smell of him: it was like the musk of the bullocks.

For a while, there was silence. Then Horitana coughed. ‘You waited for me?’

‘For someone who has a reward posted for him?’ Erenora retorted, her usual sense of independence returning. ‘Maybe I have, maybe I haven’t. And you should know better than to bring a rifle into Parihaka.’

His eyes clouded, as if the memories of the wars were painful to him. Then he looked her up and down. ‘You’ve grown as tall as me,’ he said, as if that were a problem, ‘and you sound very proud. Perhaps I should reconsider the plans that have always been in my heart to make you mine.’

He had the gall to wink at Ripeka in Erenora’s presence. Ripeka was lapping it up.

‘Alas,’ he sighed, ‘I am a man of honour …’

‘You had better be!’ Erenora said. Was he deaf? Could he not hear the loud beating of her heart: ka patupatu tana manawa? ‘As for my height,’ she continued, ‘the problem is easily solved … you must get used to it.’

Of course Ripeka was jealous but, really, she was never in the running.

Erenora was finally reunited with the orphan boy she had always loved, but she wasn’t an apple that fell too readily off a tree. Yes, she was proud and she knew her own worth. Horitana would have to do much more than simply profess his love to win her.

After a suitable time of wooing, throughout which Huhana was a vigilant duenna, Erenora and Horitana finally tied the knot. Although it was difficult to retain her virgin status in the face of Horitana’s persistent ardour, she was a virgin when she married him; he was twenty-two.

Te Whiti himself presided over their wedding and led them to their marriage bed.

‘My love for you is like a cloak of many feathers,’ Erenora said to Horitana. ‘Let me throw it around your shoulders.’

His voice was full of gratitude. ‘Erenora …’

‘And now, let me plait and weave the flax of our desire into each other’s heart and tighten the tukutuku so that it will never break apart.’

This time, Horitana’s voice flooded with urgency. ‘Erenora.’

1

By musket, sword and cannon, Major-General Chute cut a murderous swathe from Whanganui to the Taranaki Bight.

Just in case he missed Maori standing in his path — whether or not they were warriors or civilians didn’t matter — he smote them down when he turned back to Whanganui. He destroyed seven pa and twenty-one kainga. He also burned crops and slaughtered livestock; if he couldn’t kill Maori, he would starve them to death. ‘There were no prisoners made in these late engagements,’ the Nelson Examiner reported, somewhat chillingly, ‘as General Chute … does not care to encumber himself with such costly luxuries.’

Astonishingly, although the Angel of Death flew over Taranaki, Parihaka escaped in what some people called the Passover. Instead, as the trumpets and bugles of war faded, a sanctuary was born beneath unfolding clouds and, with the mountain looking on, the pilgrims built a citadel.

2

‘It was winter and bitterly cold, the wind coming off the flanks of Taranaki, when our prophets put an end to our pilgrimage. The peak was wearing a coronet of snow and the landscape all around was fringed with ice and snow drifts.

‘In the beginning, the only cover to be had from the driving rain was provided by the bullocks. The old people herded them to form a circle and then commanded them to lie down. Then they said to us, “Tataraki’i, huddle close to our beloved companions.” Oh, I will never forget the heat coming from those noble animals as they pillowed our heads and blew their steaming warmth over us.

‘When the weather was really stormy, the adults had to provide extra shelter by standing and becoming the roofs above us; they were like sentinels, and they sang to each other to keep themselves awake until the storm passed. Why did they do that? Well, as Huhana told me one morning, “Our children are our future. Without you, why keep going?”

‘Eventually we erected makeshift tents like the camp we had at Nga Kumikumi, but we couldn’t start raising our kainga quite yet, oh no. From my recollection it was 1867 and the spring tides, nga tai o Makiri, were especially high and strong. At those times when the moon switched from full to new, our people gathered kai moana, our staple diet. You can’t tell the spring tides, “Wait, we’re not ready!” or the fish to stop rising at the most propitious time of all for fishing! We were soon busy harvesting both shellfish and sea fish, like shark, and also trapping eels when they swirled upwards to suck at the surface of the water.

‘At the same time as this was happening, Te Whiti and Tohu were also concerned to get some seeds into the ground. If we missed the planting time, there would be no food in the coming year. Not until we had some cultivations under way were the two prophets satisfied. “Now we raise Parihaka,” Te Whiti said. And so we began the work of clearing the site. We were so happy to start building the kainga. Even the tataraki’i, how they chirruped!

‘Meanwhile, Huhana had fully taken me to her breast as my mother. She also took in two other orphans, Ripeka and Meri, as w’angai or adopted daughters. She said to Te Whiti, “If I have to take in one it might as well be three”, which was her way of saying that she had an embrace that could accommodate us all.

‘I can remember only hard-working but happy times through that warming weather. Ripeka and Meri and I helped the adults smooth down the earth and take the stones away so that the houses could be built. Ripeka was the pretty one, with her lovely face and shapely limbs. As for Meri, she always tried to please, and that endeared her to everyone.

‘Both my sisters were older than me but somehow they were followers rather than leaders. For instance, we had a small sled on which Ripeka and Meri would pile the stones, but I was the one who pulled the sled from the construction sites. Even in those days, although I was always slim, I was strong. Ripeka would follow my instructions but Meri was often disobedient. One time she thought she would give me a rest and pull the sled while I wasn’t looking, but she took it to the wrong place and unloaded it there. “I was only trying to help,” she said to me plaintively as I reloaded the sled. “Please, Meri, don’t try,” I answered.

‘It took us the best part of the season and then the summer to raise Parihaka. I think one of the reasons why it happened so quickly was that Te Whiti discouraged the carving of meeting houses or any such adornment on other w’are. He was more concerned with us concentrating on food-gathering and sustaining ourselves. He also wanted to discourage any competition between the various tribal peoples who came to live with us.

‘The days turned hot, and we sweated under the burning sun. Te Whiti ordered the men to build the houses in rows and very close together. Those men were out day and night selecting good trees to cut down for all the w’are. They sawed the trunks into slabs of wood, two-handed saws they used in those days, one man at each end. When a w’are’s roof was raised, we would cheer, sing and dance in celebration!

‘My sisters and I graduated to helping the women thatch the roofs with raupo, which the men brought from the bush. Huhana was always yelling to me, “Erenora, hop onto the roof.” Men mostly did the thatching but, sometimes, they were busy on other heavier work — and Huhana knew I had good balance and was not afraid of heights. The women threw the thatch up to me and I laid it in place. After that, my sisters and I helped the women as they made the tukutuku panels for the walls of the houses: I sat on one side pushing the reeds through the panels to my sisters on the other side; they would push the reeds back and, of course, Meri’s reed kept coming through at the wrong place. Why was she so hopeless?

‘Everybody was vigorous with the work. Later, my sisters helped to make blankets, pillows and clothing, but I had no patience with such feminine tasks and preferred to work outside with the men. Te Whiti and Tohu had marked out the surrounding country for cultivations and there were a lot of fences to construct, and small roadways and pathways between them. As we worked, we sang to each other and praised God for bringing us here. There could have been no better place really. The Waitotoroa Stream was ideal as a water supply, and it would have been almost impossible to sustain ourselves without it.’

‘It must have been around this time, as autumn descended and the leaves began to fall, that Te Whiti had word from the South Island that the Reverend Johann Riemenschneider had died. Apparently, after he and his wife had left Warea in 1860, Rimene had spent two years in Nelson. Then he accepted an invitation from a society in Dunedin to do mission work among the Maori people in the city. He lived four years there, and his body was committed to the earth in Port Chalmers.

‘Te Whiti mourned the German missionary, telling us, “Rimene did not achieve great victories but he sowed the seed of God so that the harvest was sure. What more can you ask from a servant of Christ?”

‘We all said a prayer for him. Now he was forever with the Lord. And I found my own karakia for him from the German phrasebook:

‘“Selig sind die Toten. Blessed are the dead.”’

3

The next few years flew by. Sometimes when Erenora looked back on them, it was as if the raising of Parihaka, so that it would stand triumphant in the sun, had taken place on one long day. Of course it hadn’t, but certainly Parihaka grew as Maori fled from the British soldiers in Taranaki.

‘From 200 people we increased to 500. Word got around, you see, that Te Whiti and Tohu were building a city, a kainga like the Biblical city of Jerusalem. We therefore mushroomed to over 1,000 as refugees poured in, driven by the encirclement of Taranaki. They were all hungry and thirsty, and some were grievously wounded. Once they had been fed and recovered, however, they had to pitch in straight away — no mucking around and having a rest! The consequence was that we were building all the time, and Parihaka was quickly forced to become a large kainga.