2. The diesel train — Morton Peto's palace — Visiting Somerleyton — The Cities of Germany in flames — The decline of Lowestoft — The former coastal resort — Frederick Farrar and the court of King James II

It was on a grey, overcast day in August 1992 that I travelled down to the coast in one of the old diesel trains, grimed with oil and soot up to the windows, which ran from Norwich to Lowestoft at that time. The few passengers there were sat in the half-light on the threadbare seats, all of them facing the engine and as far away from each other as they could be, and so silent, that not a word might have passed their lips in the whole of their lives. Most of the time the carriage, pitching about unsteadily on the track, was merely coasting along, since there is an almost unbroken gentle decline towards the sea; at intervals, though, when the gears engaged with a jolt that rocked the entire framework, the grinding of cog wheels could be heard for a while, till, with a more even pounding, the onward roll resumed, past the back gardens, allotments, rubbish dumps and factory yards to the east of the city and out into the marshes beyond. Through Brundall, Buckenham and Cantley, where, at the end of a straight roadway, a sugar-beet refinery with a belching smokestack sits in a green field like a steamer at a wharf, the line follows the River Yare, till at Reedham it crosses the water and, in a wide curve, enters the vast flatland that stretches southeast down to the sea. Save for the odd solitary cottage there is nothing to be seen but the grass and the rippling reeds, one or two sunken willows, and some ruined conical brick buildings, like relics of an extinct civilization. These are all that remains of the countless wind pumps and windmills whose white sails revolved over the marshes of

Halvergate and all along the coast until in the decades following the First World War, one after the other, they were all shut down. It's hard to imagine now, I was once told by someone who could remember the turning sails in his childhood, that the white flecks of the windmills lit up the landscape just as a tiny highlight brings life to a painted eye. And when those bright little points faded, the whole region, so to speak, faded with them. — After Reedham we stopped at Haddiscoe and Herringfleet, two scattered villages just visible in the distance; and at the next station, the halt for Somerleyton Hall, I got out. The train ground into motion again and disappeared round a gradual bend, leaving a trail of black smoke behind it. There was no station at the stop, only an open shelter. I walked down the deserted platform, to my left the seemingly endless expanses of the marshes and to my right, beyond a low brick wall, the shrubs and trees of the park. There was not a soul about, of whom one might have asked the way. At one time, I thought, as I slung my rucksack over my shoulder and crossed the track, things would have been quite different here. Almost everything a residence such as Somerleyton required for its proper upkeep and all that was necessary in order to sustain a social position never altogether secure would have been brought in on the railway from other parts of the country and would have arrived at this station in the goods van of the olive-green-liveried steam train — furnishings, equipment and impedimenta of every description, the new piano, curtains, and portières, the Italian tiles and fittings for the bathrooms, the boiler and pipes for the hothouses, supplies from the market gardens, cases of hock and Bordeaux, lawn mowers and great boxes of whalebone corsets and crinolines from London. And now there was nothing any more, nobody, no stationmaster in gleaming peaked cap, no servants, no coachman, no house guests, no shooting parties, neither gentlemen in indestructible tweeds nor ladies in stylish travelling clothes. It takes just one awful second, I often think, and an entire epoch passes. Nowadays Somerleyton Hall, like most important country houses, is open to a paying public in the summer months. But these people do not arrive by the diesel train; they drive in at the main gates in their own automobiles. If one nevertheless arrives at the railway halt, as I did, and has no desire to walk all the way round to the front, one has to climb the wall like some interloper and struggle through the thicket before reaching the park. It seemed to me like a curious object lesson from the history of evolution, which at times repeats its earlier conceits with a certain sense of irony, that when I emerged from the trees I beheld a miniature train puffing through the fields with a number of people sitting on it. They reminded me of dressed-up circus dogs or seals; and at the front of the train, a ticket satchel slung about him, sat the engine driver, conductor and controller of all the animals, the present Lord Somerleyton, Her Majesty The Queen's Master of the Horse.

In the Middle Ages, the manor of Somerleyton was held by the FitzOsberts and the Jernegans, but over the centuries ownership of the estate passed to a number of families related either by blood or by marriage. From the Jernegans it feel to the Wentworths, from the Wentworths to the Garneys, from the Garneys to the Allens, and from the Allens to the Anguishes, whose line became extinct in 1843. In that year, Lord Sydney Godolphin Osborne, a distant relative of that extinct family chose not to take up his inheritance and instead sold the entire property to Sir Morton Peto. Peto, who came of humble origins and who had worked his way up from bricklayer's labourer, was just thirty when he purchased Somerleyton, but was already among the foremost entrepreneurs and speculators of his time. In the planning execution of prestigious construction projects in London, among them Hungerford Market, the Reform Club, Nelson's Column and a number of West End theatres, he set new standards in every respect. Moreover, his financial interests in the railways being built in Canada, Australia, Africa, Argentina, Russia and Norway had made him a truly massive fortune in the shortest of times, so that he was now ready to crown his ascent into the highest social spheres by establishing a country residence, the comfort and extravagance of which would eclipse everything that nation had hitherto seen. And indeed Morton Peto's dream, a princely palace in what was known as the Anglo-Italian style, along with its interiors, was completed within a very few years on the site of the old, demolished hall. As early as 1852, The Illustrated London news and other society periodicals were running the most effusive reports on the new Somerleyton. In particular, it was famed for the scarcely perceptible transitions from interiors to exterior; those who visited were barely able to tell where the natural ended and the man-made began. There were drawing rooms and winter gardens, spacious halls and verandahs. A corridor might end in a ferny grotto where fountains ceaselessly plashed, and bowered passages criss-crossed beneath the dome of a fantastic mosque. Windows could be lowered to open the interior onto the outside, and inside the landscape was replicated on the mirror walls. Palm houses and orangeries, the lawn like green velvet, the baize on the billiard tables, the bouquets of lowers in the morning and retiring rooms and in the majolica vases on the terrace, the birds of paradise and the golden pheasants on the silken tapestries, the goldfinches in the aviaries and the nightingales in the garden, the arabesques in the carpets and the box-edged flower beds — all of it interacted in such a way that one had the illusion of complete harmony between the natural and the manufactured. The most wonderful sight of all, according to one contemporary description, was Somerleyton of a summer's night, when the incomparable glasshouses, borne on cast-iron pillars and braces and seemingly weightless in their filigree grace, shed their gleaming radiance on the dark. Countless Argand burners backed with silver-plated reflectors, the white flames consuming the poisonous gas with a low hissing sound, cast an immense brightness that pulsated like the current of life that runs through the earth.

Not even Coleridge, in an opium dream, could have imagined a more magical scene for his Mongol overlord, Kubla Khan. And now, the writer continues, suppose that at some point during a soirée you and someone close to you climb the campanile at Somerleyton, you stand on the gallery at the very top and are brushed by the soundless wing of a bird gliding by in the night! The intoxicating scent of linden blossom is wafted up from the great avenue. Below, you see the steep roofs tiled with dark blue slate, and in the snow-white glow from the shimmering glasshouses the level blackness of the lawns. Further off in the park drift the shadows of Lebanese cedars; in the deer enclosure, the wary animals keep one eye open in their sleep; and beyond the furthermost perimeter, away toward the horizon, the marshes extend and the sails of the mills are turning in the wind.

Somerleyton strikes the visitor of today no longer as an oriental palace in a fairy tale. The glass-covered walks and the palm house whose lofty dome used once to light up the nights, were burnt out in 1913 after a gas explosion and subsequently demolished. The servants who kept all in good order, the butlers, coachmen, chauffeurs, gardeners, cooks, sempstresses, and chambermaids, have long since gone. The suites of rooms now make a somewhat disused, dispirited impression. The velvet curtains and crimson blinds are faded, the settees and armchairs sag, the stairways and corridors which the guided tour takes one through are full of bygone paraphernalia. A camphor wood chest which may once have accompanied a former occupant of the house on a tour of duty to Nigeria or Singapore now contains old croquet mallets and wooden balls, golf clubs, billiard cues and tennis racquets, most of them so small they might have been intended for children, or have shrunk in the course of the years. The walls are hung with copper kettles, bedpans, hussars' sabres, African masks, spears, safari trophies, hand-coloured engravings of Boer War battles—Battle of Pieters Hill and Relief of Ladysmith: A Bird's-Eye View from an Observation Balloon—and a number of family portraits painted perhaps some time between 1920 and 1960 by an artist not untouched by Modernism, the plaster-coloured faces of the sitters mottled with scarlet and purple blotches. The stuffed polar bear in the entrance hall stands over three yards tall. With its yellowish and moth-eaten fur, it resembles a ghost bowed by sorrows. There are indeed moments, as one passes through the rooms open to the public at Somerleyton, when one is not quite sure whether one is in a country house in Suffolk or some kind of no-man's-land, on the shores of the Arctic Ocean or in the heart of the dark continent. Nor can one readily say which decade or century it is, for many ages are superimposed here and coexist. As I strolled through Somerleyton Hall that August afternoon, amidst a throng of visitors who occasionally lingered here or there, I was variously reminded of a pawnbroker's or an auction hall. And yet it was the sheer number of things, possessions accumulated by generations and now waiting, as it were, for the day when they would be sold off, that won me over to what was, ultimately, a collection of oddities. How uninviting Somerleyton must have been, I reflected, in the days of the industrial impresario Morton Peto, MP, when everything, from the cellar to the attic, from the cutlery to the waterclosets, was brand new, matching in every detail, and in unremittingly good taste. And how fine a place the house seemed to me now that it was imperceptibly nearing the brink of dissolution and silent oblivion. However, on emerging into the open air again, I was saddened to see, in one of the otherwise deserted aviaries, a solitary Chinese quail, evidently in a state of dementia, running to and fro along the edge of the cage and shaking its head every time it was about to turn, as if it could not comprehend how it had got into this hopeless fix.

The grounds, in contrast to the waning splendour of the house, were now at their evolutionary peak, a century after the heyday of Somerleyton. The flower beds might well have been better tended and more gloriously colourful, but today the trees planted by Morton Peto filled the air above the gardens, and several of the ancient cedars, which were there to be admired by visitors even then, now extended their branches over well-nigh a quarter of an acre, each an entire world unto itself. There were sequoias towering more than sixty yards, and rare oriental planes, the outermost extremities of which had bowed down as low as the lawn, securing a hold where they touched the ground, to shoot up once more in a perfect circle. It was easy to imagine this species of plane tree spreading over the country, just as concentric circles ripple across water, the parents becoming weaker and dying off from within as the progeny conquers the land about them. Some of the lighter-coloured trees seemed to drift like clouds above the the parkland. Others were of a deep, impenetrable green. Like terraces the crowns rose one upon another, and if one defocused one's eyes just slightly it was like looking upon mountains covered with vast forests. Yet the densest and greenest was for me the Somerleyton yew maze, in the heart of the mysterious estate, where I became so completely lost that I could not find the way out again until I resorted to drawing a line with the heel of my boot across the white sand of every hedged passage that had proved to be a dead end. Later, in one of the long hothouses built against the brick walls of the kitchen garden, I struck up a conversation with William Hazel, the gardener who now looks after Somerleyton with the help of several odd-job men. When he realized where I was from he told me that during his last years at school, and his subsequent apprenticeship, his thoughts constantly revolved around the bombing raids then being launched on Germany from the sixty-seven airfields that were established in East Anglia after 1940. People nowadays hardly have any idea of the scale of the operation, said Hazel. In the course of one thousand and nine days, the eighth airfleet alone used a billion gallons of fuel, dropped seven hundred and thirty-two thousand tons of bombs, and lost almost nine thousand aircraft and fifty thousand men. Every evening I watched the bomber squadrons heading out over Somerleyton, and night after night, before I went to sleep, I pictured in my mind's eye the German cities going up on flames, the firestorms setting the heavens alight, and the survivors rooting about in the ruins. One day when Lord Somerleyton was helping me prune the vines in this greenhouse, for something to do, said Hazel, he explained the Allied carpet-bombing strategy to me, and some time later he brought me a big relief map of Germany. All the place names I had heard on the news were marked in strange letters alongside symbolic picture sof the towns that varied in the number of gables, turrets and towers according to the size of population; and moreover, in the case of particularly important cities, there were emblems of features associated with them, such as Cologne cathedral, the Römer in Frankfurt, or the statue of Roland in Bremen. Those tiny images of towns, about the size of postage stamps, looked like romantic castles, and I pictured the German Reich as a medieval and vastly enigmatic land. Time and again I studied the various regions on the map, from the Polish border to the Rhine, from the green plains of the north to the dark brown Alps, partly covered with eternal snow and ice, and spelled out the names of the cities, the destruction of which had just been announced: Braunschweig and Würzburg, Wilhelmshaven, Schweinfurt, Stuttgart, Pforzheim, Düren, and dozens more. In that way I got to know the whole country by heart; you might even say it was burnt into me. At all events, ever since then I have tried to find out everything I could that was in any way connected with the air in the air. In the early Fifties, when I was in Lüneburg with the army of occupation, I even learnt German, after a fashion, so that I could read what the Germans themselves had said about the bombings and their lives in the ruined cities. To my astonishment, however, I soon found the search for such accounts invariably proved fruitless. No one at the time seemed to have written about their experiences or afterwards recorded their memories. Even if you asked people directly, it was as if everything had been erased from their minds. As for myself, though, whenever I close my eyes, to this day, I see the formations of bombers, Lancasters and Halifaxes, Liberators and Flying Fortresses, going out towards Germany across the grey North Sea, and then straggling home in the dawn. In early April 1945, not long before the War ended, said Hazel, sweeping up the vine shoots he had cut, I saw two American Thunderbolts crash here, over Somerleyton, It was a fine Sunday morning. I had been helping my father with an urgent repair job up on the campanile, which is really a water tower. When we were finished we stood on the look-out platform, from where there is a view right out to sea. We had hardly had time to look around when the two planes, returning from a patrol, staged a dogfight over the estate, out of sheer high spirits, I suppose. We could see the pilots' faces clearly in their cockpits. The engines roared as they chased after each other, or flew side by side in the bright spring air, till their wing tips touched as they banked. It had seemed like a friendly game, said Hazel, and yet now they fell, almost instantly. When they disappeared beyond the white poplars and willows, I went all tense waiting for the crash. But there were no flames or clouds of smoke. The lake swallowed them up without a sound. Years later we pulled them out. Big Dick, one of the airplanes was called and the other Lady Loreley. The two pilots, Flight Lieutenants Russel P. Judd from Versailles, Kentucky, and Louis S. Davies from Athens, Georgia, or what bits and bones had remained of them, were buried here in the grounds.

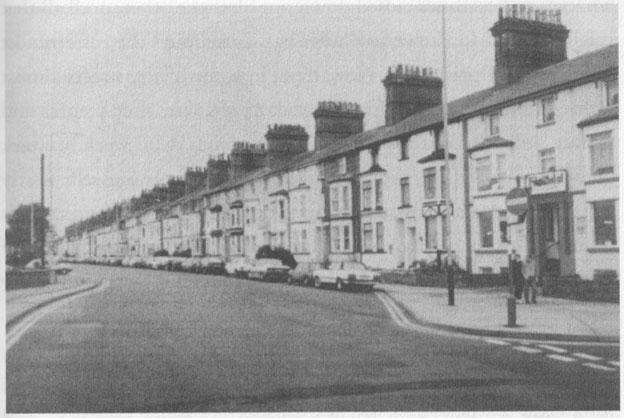

After I had taken my leave of William Hazel I walked for a good hour along the country road from Somerleyton to Lowestoft, passing Blundeston prison, which rises out of the flatland like a fortified town and keeps within its walls twelve-hundred inmates at any one time. It was already after six in the evening when I reached the outskirts of Lowestoft. Not a living soul was about in the long streets I went through,

and the closer I came to the town centre the more what I saw disheartened me. The last time I had been in Lowestoft was perhaps fifteen years ago, on a June day that I spent on the beach with two children, and I thought I remembered a town that had become something of a backwater but was nonetheless very pleasant; so now, as I walked into Lowestoft, it seemed incomprehensible to me that in such a relatively short period of time the place could have become so run down. Of course I was aware that this decline had been irreversible ever since the economic crises and depressions of the Thirties; but around 1975, when they were constructing the rigs for the North Sea, there were hopes that things might change for the better, hopes that were steadily inflated during the hardline capitalist years of Baroness Thatcher, till in due course they collapsed in a fever of speculation. The damage spread slowly at first, smouldering underground, and then caught like wildfire. The wharves and factories closed down one after the other, until all that might be said for Lowestoft was that it occupied the easternmost point in the British Isles. Nowadays, in some of the streets almost every other house is up for sale; factory owners, shopkeepers and private individuals are sliding ever deeper into debt; week in, week out, some bankrupt or unemployed person hangs himself; nearly a quarter of the population is now practically illiterate, and there is no sign of an end to the encroaching misery. Although I knew all of this, I was unprepared for the feeling of wretchedness that instantly seized hold of me in Lowestoft, for it is one thing to read about unemployment blackspots in the newspapers and quite another to walk out on a cheerless evening, past rows of run-down houses with mean little front gardens; and, having reached the town centre, to find nothing but amusement arcades, bingo halls, betting shops, video stores, pubs that emit a sour reek of beer from their dark doorways, cheap markets, and seedy bed-and-breakfast establishments with names like Ocean Dawn, Beachcomber, Balmoral, or Layla Lorraine. It was difficult to imagine the holidaymakers and commercial travellers who would want to stay there, nor was it easy — as I climbed the steps coated with shiny blue paint up to the entrance — to recognize the Albion as the "hotel on the promenade of a superior description" recommended in my guidebook, which had been published shortly after the turn of the century. I stood for a good while in the empty lobby, and wandered through the public rooms, which were completely deserted even now at the height of the season — if one can speak of a season in Lowestoft — before I happened upon a startled young woman who, after hunting pointlessly through the register on the reception desk, handed me a huge room key attached to a wooden pear. I noticed that she was dressed in the style of the Thirties and that she avoided eye contact; either her gaze remained fixed on the floor or she looked right through me as if I were not there. That evening I was the sole guest in the huge dining room, and it was the same startled person who took my order and shortly afterwards brought me a fish that had doubtless lain entombed in the deep-freeze for years. The breadcrumb armour-plating of the fish had been partly singed by the grill, and the prongs of my fork bent on it. Indeed it was so difficult to penetrate what eventually proved to be nothing but an empty shell that my plate was a hideous mess once the operation was over. The tartare sauce that I had had to squeeze out of a plastic sachet was turned grey by the sooty breadcrumbs, and the fish itself, or what feigned to be fish, lay a sorry wreck among the grass-green peas and the remains of soggy chips that gleamed with fat. I no longer recall how long I sat in that dining room with its gaudy wallpaper before the nervous young woman, who evidently did all the work in the establishment single-handed, scurried out from the thickening shadows in the background to clear the table. She may have appeared the moment I put down my knife and fork, or perhaps an hour had passed; all I can remember are the scarlet blotches which appeared from the neckline of her blouse and crept up her throat as she bent for my plate. When she had flitted away once more I rose and crossed to the semi-circular bay window. Outside was the beach, somewhere between the darkness and the light, and nothing was moving, neither in the air nor on the land nor on the water. Even the white waves rolling in to the sands seemed to me to be motionless.

The following morning, when I left the Albion Hotel with my rucksack over my shoulder, Lowestoft had reawoken to life, under a cloudless sky. Passing the harbour, where dozens of decommissioned and unemployed trawlers rode at their moorings, I headed south through streets that were now congested with traffic and filled with blue petrol fumes. Once, right by Lowestoft Central station, which had not been refurbished since it was built in the nineteenth century, a black hearse decked out with wreaths slid past me amidst the other vehicles. In it sat two earnest-faced undertaker's men, the driver and a co-driver, and behind them, in the loading area, as it were, someone who had but recently departed this life was lying in his coffin, in his Sunday best, his head on a little pillow, his eyelids closed, hands clasped, and the tips of his shoes pointing up. As I gazed after the hearse I thought of that working lad from Tuttlingen, two hundred years ago, who joined the cortège of a seemingly well known merchant in Amsterdam and then listened with reverence and emotion to the graveside oration although he knew not a word of Dutch. If before then he had marvelled with envy at the tulips and starflowers behind the windows, and at the crates, bales and chests of tea, sugar, spices and rice that arrived in the docks from the faraway East Indies, from now on, when occasionally he wondered why he had acquired so little on his way through the world, he had only to think of the Amsterdam merchant he had escorted on his last journey, of his big house, his splendid ship, and his narrow grave. With this story in my head I made my way out of a town on which the marks of an insidious decay were everywhere apparent, a town which in its heyday had been not only one of the foremost fishing ports in the United Kingdom but also a seaside resort lauded even abroad as "most salubrious". At that time, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, a number of hotels were built on the south bank of the River Waveney, under the direction of Morton Peto. They met all the requirements of London society circles, and, as well as the hotels, pump rooms and pavilions were built, churches and chapels for every denomination, a lending library, a billiard hall, a tea house that resembled a temple, and a tramway with a magnificent terminus. A broad esplanade, avenues, bowling greens, botanical gardens, and sea- and freshwater baths were established, as were associations for the promotion and the beautification of Lowestoft. In no time at all, notes a contemporary account, Lowestoft had risen to pride of place in the public esteem, and now possessed every facility requisite for a bathing resort of repute. Anyone who considered the elegance and perfection of the buildings recently constructed along the south beach, the article continued, would doubtless recognize that everything, from the overall plan to the very last detail, had been informed and shaped by the principles of rationality in the most advantageous way. The crowning glory of the enterprise, which was in every respect exemplary, was the new pier, which stretched four hundred years out into the North Sea and was considered the most beautiful anywhere along the eastern coast of England. The promenade deck was made of African mahogany planking, and the white pier buildings, which were illuminated after nightfall by gas flares, included a reading and music room with tall mirrors around the walls. Every year at the end of September, as my friend Frederick Farrar told me a few months before he died, a charity ball was held there under the patronage of a member of the royal family to mark the close of the regatta. Frederick was born in Lowestoft in 1906 (far too late, as he once observed to me) and grew up there amidst the care and attention of his three sisters Violet, Iris and Rose. Then in early 1914 he was sent to a preparatory school near Flore in Northamptonshire. The great pain of separation, Frederick recalled, was with me for a long time, especially before going to sleep or when I was tidying my things; but one evening at the start of my second year, when we were told to assemble on the west forecourt, this pain was transformed within me into a kind of perverse pride. We were there to hear a patriotic speech from our headmaster, who told us of the just causes and higher significance of the war which had broken out during the school holidays. When he had finished, said Frederick, a junior cadet named Francis Browne, whom I have not forgotten to this day, played the Last Post on a bugle. From 1924 to 1928, at the wish of his father, who was a solicitor in Lowestoft and for a lengthy period also the consul of Denmark and of the Ottoman Empire, Frederick read law at Cambridge and London, and subsequently as he once said with a certain horror, spent more than half a century in lawyers' chambers and courtrooms. Since judges in England generally remain in office well into old age, Frederick had only just retired when in 1982 he bought a house in our neighbourhood and devoted himself to breeding rare roses and violets. I need hardly add that the iris was also one of his favourites. In the course of ten years he grew dozens of varieties of these flowers in the garden he had established, with the help of a young boy who came round almost every day to lend him a hand. His garden was one of the loveliest in the whole region, and towards the end of his life, after a stroke had left him very frail, I often sat there with him, listening to tales of Lowestoft and the past. And it was in that garden, one cloudless day in May, that Frederick died; as he was making his morning round, he somehow managed to set fire to his dressing gown with the cigarette lighter he always kept in his pocket. The garden boy found him an hour later, unconscious and with severe burns from head to foot, in a cool, half-shaded place, where the tiny viola labradorica with its almost black leaves had spread and established a regular colony. Frederick succumbed to his injuries that same day. At the funeral in the little graveyard at Framingham Earl I could not help thinking of that child bugler Francis Browne, playing into the night in a Northamptonshire schoolyard in the summer of 1914, and the white pier at Lowestoft, which reached out so far into the sea in those days. Frederick had told me that on the evening of the charity ball the common folk, who in the nature of things were not admitted, rowed out to the end of the pier in a hundred or more boats and barges, to watch, from their bobbing, drifting vantage points, as fashionable society swirled to the sound of the orchestra, seemingly borne aloft in a surge of light above the water, which was dark and at that time in early autumn usually swathed in mist. If I now look back at those times, Frederick once said, it is as if I were seeing everything through flowing white veils: the town like a mirage over the water, the seaside villas right down to the shore surrounded by green trees and shrubs, the summer light, and the beach, across which we have just returned from an outing, Father walking ahead with one or two gentlemen whose trousers are rolled up, Mother by herself with a parasol, my sisters with their skirts gathered in one hand, and the servants bringing up the rear with the donkey, between whose panniers I am sitting on my perch. Once, years ago, said Frederick, I even dreamed of that scene, and our family seemed to me like the court of King James II in exile on the coast of The Hague.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ