Here you will meet unique sidewhiskers, tucked under the necktie with extraordinary and astounding skill, sidewhiskers that are velvety, satiny, black as sable or as coal, but, alas belonging to the Foreign Office alone. Providence has refused to permit civil servants from other departments to sport black side-whiskers; to their very great chagrin, they must wear red ones.

The blurring of the distinction between the part and the whole - Gogol's characteristic grotesque synecdoche - was to strike a chord in several

modernist writers, for whom it became a means of conveying intensity of emotion, the disintegration of personality, or essential psychological features. Thus, Maiakovskii's lyrical persona in "A Cloud in Trousers" (1915) cries: "But can you turn yourself inside out as I can, so that you are nothing but lips?"; and the hero of Zamiatin's We (written 1920-21, first complete publication in Russian 1952) declares: "imagine a human finger cut off from the whole, from the hand - a separate human finger hunched up, running in a series of hops along the glass pavement. That finger was me" (Entry 18).

In the context of Russian Modernism, the grotesque fantasy of "The Nose" is of particular importance. This story in which a bumptious civil servant, "Major" Kovalev, awakens one day to find that he has lost his nose and later sees it in the guise of a general riding round in a carriage, is astonishingly "modern" for a work written in the first half of the nineteenth century. It is deliberately elusive, with a characteristic dream-like fluidity that extends to every level. Nothing here is stable; character, plot, language, point of view, dimensions, even such a basic category as "animate"/ "inanimate" - all are in constant flux, and there is no fixed point that the reader can hold on to with certainty. One moment the nose is discovered baked in a loaf of bread, the next it is wearing a general's uniform during a service in the Kazan Cathedral and Kovalev approaches it tentatively, since it appears to outrank him. When it is finally recovered, Kovalev tries to stick it back on the smooth place left on his face, but it falls to the table with a dull thud, like something inorganic; later still it reappears in its proper place, once more an integral part of an organism. Some critics have seen in "The Nose" little more than an amusing piece of whimsy, yet the underlying themes of sexual and social anxiety and alienation mark the work as a precursor of Russian Modernism no less clearly than do the stylistic features. A further similarity comes with reader response. The amusement that the reader of "The Nose" is likely to feel will almost certainly be accompanied by an uneasiness that is a characteristic reaction to many of the modernist works of the first two decades of the twentieth century. Gogol's grotesque, unstable fantasy is to find many echoes in the years to come, in works by Belyi, Maiakovskii, Zamiatin, and Olesha, as well as in Kharms's literature of the absurd.

The similarities between Gogol's St. Petersburg tales and the early Dostoevskii have been widely recognized, particularly in the case of The Double, which takes thematic and stylistic elements that had been found earlier in "The Nose" and "Notes of a Madman" and relates them to the onset of the hero's schizophrenia. The modernist features of fractured style, anxiety, and social alienation in the city are all to be found in Dostoevskii

as in Gogol, but in the younger writer they are more explicitly related to their metaphysical and psychological undercurrents. If Gogol's anticipation of Modernism is instinctive, then Dostoevskii's appears to me to be the result of a profound understanding of the great shift in consciousness that was about to take place and that would be expressed in different spheres of thought by Freud, Nietzsche, Lobachevskii, Einstein, and many others. Dostoevskii both anticipates and, through his enormous influence on twentieth-century art and thought, helps to shape modern consciousness,4 a process that can be seen nowhere more clearly than in two of the novelist's St. Petersburg works, Notes from Underground and Crime and Punishment. Here the protagonists' isolation is not only social, but also existential. The question of identity and how it can be determined runs through both works.5 In their attempts to find out who they are, and in their eschewal of definition by such extraneous factors as class, wealth, nationality, or self-interest, the Underground Man and Raskolnikov are deeply modern heroes. Similarly, the uneasy, apocalyptic atmosphere of The Devils (1871-72), a sense of being on the edge of catastrophe, anticipates one of the central features of modern consciousness.

The form which Dostoevskii employed for his examination of the existential and psychological condition of modern man was the realistic novel, but it was a new kind of realism, what he himself termed "realism in a higher sense," and in its blend of verisimilitude and fantasy, in its instability and unpredictability, it was exactly suited to the depiction of contemporary life, and was to be a major influence throughout the next century. It is beyond the scope of this essay to examine in any detail the nature of Dostoevskii's realism (a topic that has been extensively discussed by many critics), but one or two examples will indicate the general nature of his innovations. First, there is the depiction of space. The city of St. Petersburg as a whole, its individual streets and buildings, and the rooms inhabited by the heroes of the works are all on the one hand "real," in that their representation is mimetic, and on the other hand they are psychological constructs, spatial analogues of the characters' minds. As has been pointed out by Leonid Grossman, Dostoevskii's depiction of St. Petersburg is the most palpable and accurate in nineteenth-century literature.6 Yet the city inhabited by the Underground Man is the physical embodiment of his psychological condition, it is "the underground." And Raskolnikov's room seems to change dimensions in accordance with his frame of mind; one moment it is tiny and stuffy, no bigger than a cupboard, the next it swells to accommodate the student himself and several visitors. Likewise, the stifling weather is both the real St. Petersburg summer climate and a metaphor for Raskolnikov's overheated, airless mind. Similar points could be made about

the handling of time, which appears to expand and contract as a function of Raskolnikov's consciousness; and about some of the secondary characters, whose inconsistencies become explicable if the characters are seen as in part real (that is portrayed by an objective narrator) and in part projections by Raskolnikov of his own preoccupations.

It is important to stress what Dostoevskii himself stressed: that the world which he depicts in Crime and Punishment is no more fantastic than the world of real experience depicted in the newspapers. Modern life in the city is intense and chaotic, and if artists are to portray it adequately they must find new forms. It is but a small step from this point to twentieth-century Modernism. That step was taken by Andrei Belyi in Petersburg (first version 1913-14, second version 1916, final version 1922). The novel's modernity is evident in the mood of anxiety and alienation that permeates the entire work and that arises out of the awareness of impending catastrophe.7 That sense of being on the edge of the abyss that is characteristic of the modernist sensibility has, in Belyi's novel, a concrete historical context, since the work is set in the autumn of 1905, when Russia was in the grip of revolutionary turmoil. The plot involves an attempt to assassinate a senior official, Senator Apollon Apollonovich Ableukhov, by planting in his home a bomb hidden in a sardine tin. The first stage of the plan, the placing of the bomb, is carried out by Apollon Apollonovich's son, Nikolai Apollonovich, who is not a revolutionary but who is bound by a promise of help made in a rash moment. Most of the novel is pervaded by an atmosphere of imminent disaster engendered in Nikolai Apollonovich and in the reader by the awareness that the bomb is ticking away and must soon explode.

The absorbing plot and convincing evocation of a particular time and place form the framework on which Belyi hangs his brilliant narrative, which has occasionally been described as the Russian Ulysses. The comparison with Joyce's novel is not entirely without foundation; Vladimir Nabokov placed both (along with works by Kafka and Proust) in his list of the four leading masterpieces of the twentieth century. Like Joyce, Belyi writes highly dynamic prose, the normal semantic significance of which is constantly supplemented by rich phonetic patterning and occasionally by experimental typographical layout. In part, the character of the prose is determined by the voice (or voices) of the narrator, who adopts a wide variety of tones from bumbling incomprehension to sweeping lyricism, and who switches between them without warning, thereby contributing to that volatility, that lack of certainty that is a key modernist concept.

The city itself is rendered with minute topographical accuracy necessitating frequent reference to a contemporary street plan, and yet it is

simultaneously that spectral, fantastic creation of Peter the Great, mythologized by Pushkin, Gogol, and Dostoevskii, that had become a vital element in the definition of Russia's national identity. Belyi is constantly aware of the works of his predecessors (the Bronze Horseman is a character), as well as the libretto of Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades, and the reader is required to place the events and characters in their cultural environment by picking up the references. St. Petersburg itself, with all its cultural and mythical significance, emerges as the novel's protagonist, every bit as alive as the human characters.

Apart from the work of Belyi, perhaps the outstanding example of the modernist novel in Russia was by Evgenii Zamiatin, in whom modern consciousness can be seen at its purest. For Zamiatin, no true writer could be settled, content with present realities; writers had to be heretics, forever restless, in constant intellectual movement, and provoking a life-affirming and creative anxiety in their readers. As he said in the essay "Tomorrow" (1919-20):

Today is doomed to die because yesterday died, and because tomorrow will be born. Such is the cruel and wise law. Cruel, because it condemns to eternal dissatisfaction those who already today see the distant peaks of tomorrow; wise, because eternal dissatisfaction is the only guarantee of eternal movement forward, eternal creation . . . The world is kept alive only by heretics.8

In Zamiatin we can see, perhaps more clearly than anywhere else, the roots of Russian Modernism in the restless spirit of Romanticism. A recurrent image in his work is that of the lone Scythian horseman forever in motion, a figure similar to Lermontov's rebellious lone white sail, and reminiscent of the constant oppositional nature of Pechorin in A Hero of Our Time (1840, definitive version 1841): "Where is he galloping? Nowhere. Why? For no reason. He gallops simply because he is a Scythian, because he has become one with his horse, because he is a centaur, and the dearest things to him are freedom, solitude, his horse, the wide open steppe."9

For Zamiatin, there can be no immutable truths, for if there were any such fixed philosophical points they would contradict the "cosmic, universal law" of constant revolution, which "is everywhere, in everything."10 His world view is Einsteinian rather than Euclidean, based on the "speeding, curved surfaces" of the new mathematics and the new cosmology rather than the plane surfaces of Euclid and the fixed forces of Newton. Given this view of a universe in constant movement, Zamiatin uses and advocates a correspondingly dynamic literary form. The nineteenth-century Realists' leisurely descriptions of landscape and character are inappropriate

in the modern age: "who will even think of looking at landscapes and genre scenes when the world is listing at a forty-five-degree angle … ? Today we can look and think only as people do in the face of death."11 The urgent anxiety of modern life demands brevity, compression, innovative syntax and imagery, and a literary vocabulary enhanced by provincialisms, neologisms, and scientific and technical terms. The syntax of Zamiatin's artistic prose is, in his own words, "elliptic, volatile"; his imagery is "sharp, synthetic, with a single salient feature - the one feature you will glimpse from a speeding car."12

Zamiatin was keenly aware of the distinctiveness of modern art. His terms for it were "synthetism" and "neo-realism," and he viewed it as a synthesis of Realism's search for the physical reality of the flesh and Symbolism's obsession with death and retreat from the everyday in quest of the spiritual. On the one hand there was "vivid, simple, strong, crude flesh: Moleschott, Büchner, Rubens, Repin, Zola, Tolstoi, Gorkii, realism, Naturalism"; on the other "Schopenhauer, Botticelli, Rossetti, Vrubel, Churlionis, Verlaine, Blök, idealism, symbolism." The modernist artist returns to the sphere of the first group, to the flesh, but with the full knowledge of the discoveries of the second group. "Thus synthesis: Nietzsche, Whitman, Gauguin, Seurat, Picasso - the new Picasso, still little known - and all of us, great and small, who work in modern art, whatever it may be called - neo-realism, synthetism, or something else."13 It is clear from this list that for Zamiatin the essence of modern art lies in sensibility rather than chronology. Whitman, for example, was born before Zola, Tolstoi, or Gorkii, yet Zamiatin considers him a Modernist and the others Realists.

Zamiatin's novel We, substantially written in 1920 and completed in 1921, exemplifies his views on modern consciousness and its formal expression; indeed, essays such as "On synthetism" and, especially, "On literature, revolution and entropy" can be read as a commentary on and explication of the novel. First, the philosophical position adopted within We reflects the view expressed in the essays that revolution must be constant and all-embracing, and that the rejection of all fixed systems of belief, be they religious or political, is a primary requirement for a true artist. In Entry 30 of the fictional diary the following conversation takes place between the rebel I-330 and the mathematician D-503:

"Darling, you're a mathematician. Even more than that, mathematics has

made you a philosopher. Well then, name the final number for me."

"Meaning? I… I don't understand. What final number?"

"The final one, the highest number, the biggest one."

"But, I, that's absurd. Since the number of numbers is infinite, how can there

be a final one?"

"Well then, how can there be a final revolution? There is no final one, revolutions are infinite."

For those brought up in the Single State, taught since early childhood that the revolution which resulted in the foundation of their present society was the last one that would ever take place, such notions of constant revolution are frightening. Surely, argues D-503, those who founded the Single State were right to do so? I-330 wholeheartedly agrees. They were right at the time, but, as with all revolutionaries, when they achieved power they tried to prevent anyone else from rebelling against them. Conviction led to dogma and, eventually, the desire to preserve the status quo at all costs. The specific political implications of passages such as this for the fledgling Soviet state are obvious. Although it is undoubtedly the prescience of Zamiatin's novel - its anticipation of twentieth-century totalitarianism -that is its most striking political feature, its satirical reflection of certain aspects of the political, social, and cultural life of Soviet Russia in the Civil War era should not be overlooked, and was sufficient to ensure that it was not published in Russia in the 1920s. Yet to interpret the theme of revolution in the novel primarily on the political plane is to minimize its significance, not least as the philosophical cornerstone of Zamiatin's Modernism.

The concept of revolution advanced in We is universal, affecting human behavior, social and political institutions, and natural phenomena alike, and is equated with movement, with energy. The opposite tendency, towards stasis, is also universal, and is referred to by Zamiatin as "entropy," a term which he characteristically borrows from science. Thus, whereas Christ is seen as historically and philosophically revolutionary, the Christian church is portrayed as the true ancestor of the Single State: a deadening body, convinced that it is right in all things, and seeking to stifle opposition to its dogma by rooting out and destroying heretics. Entropy and dogma affect even the apparently objective world of mathematics. The conformist D-503 favors those branches of mathematics concerned with certainty, predictability, integration, and the geometry of plane surfaces and fixed solid objects. His heroes are Euclid, Pythagoras, and the early eighteenth-century English mathematician Brook Taylor, and he appears to have no knowledge of, or no esteem for, those nineteenth- and twentieth-century mathematicians whose work supported philosophical notions of uncertainty and relativity. For Zamiatin himself, as for his heroine I-330, the desire for complete certainty, whether in philosophy, religion, mathematics, or any other area, runs counter to the laws of thermodynamics. As I-330 says: "Surely, as a mathematician, you understand that only differ-

ences, differences of temperature, only contrasts in heat, only that makes for life? And if everywhere throughout the universe all bodies are equally warm or equally cool . . . They've got to be smashed into each other - so there'll be fire, explosion, inferno" (Entry 30).

Zamiatin's philosophy provokes unease and anxiety. It permits no comforting notions of eventual peace, no ultimate goal, no heaven, whether on Earth or elsewhere; instead, it promises only "the torment of endless movement" (Entry 28). In this it is modernist thought, strikingly similar in some respects to that of Nietzsche.14

A second aspect of the content of We that marks it as a modernist text is the prominence of the irrational and the subconscious. There is no evidence that Zamiatin believed in the primacy of the irrational, but in the societies which he depicts (not only the Single State but also the middle-class England of "Islanders," 1917) it has been largely suppressed, thereby destroying that balance between reason and the irrational that, he argues, is essential for the wholeness of the personality. Hence his apparent championing of irrationality. Attempting to explain to D-503 who the Mephi are, I-330 says: "Who are they? The half that we have lost. There's H2 and there's O, but in order to get H20 - streams, seas, waterfalls, waves, storms - the two halves must unite" (Entry 28). The Single State has split the human personality into its rational and irrational components and has almost succeeded in eradicating the latter. But just as water ceases to be water when either of its two elements is removed, so do people cease to be people when their irrational side is repressed. Under the influence of an overwhelming and uncomprehended wave of sexual desire for I-330, D-503's dormant irrationality is aroused, manifesting itself in dreams, in his synaesthetic perception of the physical world around him, especially his perception of color, and in the increasingly original and creative language of his diary entries.

Among the many influences on Zamiatin, mention should be made of Dostoevskii. Much in We, including the role of the irrational in human behavior, and the philosophical issue of the relationship between freedom and happiness, had been encountered earlier in Notes from Underground, The Devils, and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). Like twentieth-century writers the world over, Zamiatin found in the work of Dostoevskii a brilliant artistic investigation of the human condition in the modern age which corresponded in many respects to his own creative concerns.15 On the philosophical level, however, there is a fundamental difference between the two: Zamiatin rejects all notions of peace and reconciliation in Christ, whereas Dostoevskii and some of his heroes, while finding it impossible to accomplish the "leap of faith," need to preserve the figure of Christ as the

only way out of the "underground," the moral and intellectual impasse that is the lot of modern man. Dostoevskii's famous dictum about preferring Christ to the truth if a choice were necessary is diametrically opposed to Zamiatin's relentless refusal to accept any fixed points of belief.

Zamiatin's modernist view of life is expressed in the correspondingly fractured, elliptical prose of We. D-503 begins his diary with the intention of explaining to the less fortunate inhabitants of other planets the near-perfect, rational way of life in the Single State. His ideal is total clarity, a transparency of language that would correspond to the transparency of the buildings in the Single State. Almost immediately, however, this ideal is compromised by the intrusion of metaphor, and as the diary proceeds, its style reflects the increasingly chaotic state of D-503's mind. Zamiatin's short, dynamic sentences, punctuated by dashes and frequently tailing off into three dots, are perfectly suited both to his own view of the nature of prose in the post-Einstein age and to D-503 's uncomprehending slide into the state of alienation and anxiety, simultaneously exhilarating and terrifying, that is the modern mode.

The extreme compression of the syntax is complemented by the use of recurrent physical leitmotifs as a kind of shorthand for characterization. The characters are frequently reduced to a single detail that simultaneously suggests physical appearance and personality or function. Thus, I-330 becomes the "X" that is formed in her face by the lines of her eyebrows and the slight furrows from her nostrils to the sides of her mouth and that serves both as a physical identification tag and as an indication of her mysterious inner world. O-90 is constantly described in terms of roundness, a detail expressing her looks, the appropriateness of her name, and the maternalism that is her primary characteristic. The doctor who tells D-503 that he has developed a soul is seen as a pair of scissors, thin, sharp and dangerous. The Guardian S-4711 always appears as a hunched, snake-like figure, the physical embodiment of his ambivalent role as apparent upholder and would-be destroyer of the Single State. His serpent-like shape also acts as a frequent reminder of the mythical level on which the novel operates: the Single State corresponds to the Garden of Eden, the Benefactor to God, D-503 to Adam, I-330 to Satan, Eve and the serpent. On occasion, when D-503 catches a fleeting glimpse of someone, recognition depends entirely on the leitmotif. This is in line with Zamiatin's view that modern prose must correspond to the pace of modern life, that, as we have seen, the image must consist only of the basic detail that would be spotted from a speeding car, yet it must be capable of suggesting the whole character.

With its rapid, elliptical syntax, its identification of single salient features

of physique and character, and its displacement of the "normal" planes of time and space - most evident in stories such as "Mamai" (1920) and "A Story about the Most Important Thing" (1923) - Zamiatin's prose corresponds to his own description of the essence of modern painting. In "On synthetism" he points out that the earthquake in geometric and philosophical thought brought about by Einstein was anticipated by "the seismograph of the new art," which had shattered accepted notions of perspective, the "X, Y and Z axes" of Realism (Zamiatin, "O sintetizme," p. 286). In describing the paintings of his friend Iurii Annenkov, Zamiatin could be describing his own prose: "he has a sense of the exceptional pace and dynamism of our epoch, a sense of time refined to hundredths of a second, the skill (characteristic of synthetism) to provide only the synthetic essence of things" (Zamiatin, "O sintetizme," p. 288).

The painterly qualities of Zamiatin's modernist prose can be seen in his handling of color and light, no less than line. Scholars have sometimes attempted to assign significance to particular colors in We. Thus, for example, the light blue of the clear sky above the Single State and the bluish-grey of the numbers' uniforms have been seen as emblematic of that society's predominant rationality; the red of I-330's lips and of the fire that burns inside her as representing the heat of passion and revolution; the yellow of the ancient dress, of the sap that covers everything in spring, and of the eyes of the beast glimpsed through the glass of the Green Wall as suggesting man's struggle for freedom, for escape to the life-giving force of the sun.16 Yet, useful as these attempts at disclosing the significance of color in We have been, they have generally failed to do justice to the complexity of the subject. In a recent article Sona S. Hoisington and Lynn Imbery have, for the first time, shown how subtle and dynamic is Zamiatin's use of color, linking him with modern painters, especially Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse.17 Hoisington and Imbery demonstrate convincingly that Zamiatin's handling of color is based on transformation rather than fixed attributes, and that the opposition between energy and entropy that is the philosophical core of the novel is conveyed through such color transformations. Most of the colors in We are, therefore, dynamic and relative rather than absolute in value, which accords with Zamiatin's concept of Modernism.

Like everything else in the Single State, light is perceived by the citizens as uniform and clear, an analogue of their rational lives. D-503 eulogizes the cloudless blue sky and the even light of the "crystalline sun" and is afraid of the fog that occasionally envelops the city, blurring the customary sharp outlines of the glass buildings. On one level, Zamiatin uses different states of light as symbols of the rational and irrational halves of his hero's

psyche. I-330 tells D-503 that besides fearing the obscurity of the fog (meaning his irrationality) he also loves it (Entry 13). But, like color, light is also used by Zamiatin in a purely painterly fashion; reflecting and refracting, it can become solid, as in the following examples: "on the mirrored door of the wardrobe - a shard of light - in my eyes"; "a sharp ray of sunlight fractures like lightning on the floor, on the wall of the wardrobe, higher, and then this cruel, flashing blade falls on I-330's thrown-back, naked neck"; "a golden sickle of sunlight on the loudspeaker" (Entries 18 and 19).

The diary form and the increasing unpredictability of the narrator focus the attention of the reader of We on the artistic medium itself, as well as on the relativity of perspective. In certain other works of Russian Modernism these issues play an even greater part. The novels of Boris Pilniak, for example, have often been criticized for their dishevelled lack of organization, their repetitiveness (the author habitually incorporated earlier texts within later ones, sometimes with little revision), and their rambling, apparently arbitrary plot development (Donat, the character who, in the early pages of The Naked Year [1922], seems most likely to develop into the novel's hero is disconcertingly killed off at the end of the first chapter). Critics from Pilniak's time to the present have voiced the suspicion that his adoption of a modernist stance merely masks an inability or unwillingness to conform to the discipline of consistent plot and character development.18 Yet to argue thus is implicitly to apply to Pilniak the inappropriate criteria of the realistic novel. The Naked Year, which owes much to Belyi and Remizov, is an attempt to convey the elemental chaos of revolution by rendering it in a prose that is itself chaotic to the point of near unintelli-gibility in places. Pilniak's text is indeterminate; it cannot be tied down to consistency of language, point of view, or moral perspective. It is driven at least as much by phonetics as by plot or characterization, with many paragraphs being structured on particular sound combinations rather than on a core of meaning. And yet, meaning does emerge through a deliberate lack of coherence in the literary medium analogous to that in Russian life. Pilniak's prose is an eclectic montage of loosely connected (and sometimes unconnected) episodes narrated in a variety of equally heterogeneous stylistic registers. It is prose that insistently draws attention to the nature of the medium and yet remains representative of Russian reality.

Pilniak's style, with colloquialisms alongside archaisms, and phonetic and rhythmic repetitive patterns, is an example of the manner known as "ornamentalism" practiced by many Russian novelists and short-story writers in the 1920s. Patricia Carden considers ornamentalism to be "simply the name attached to the appearance of Modernism in Russian

prose" ("Ornamentalism and Modernism," p. 49). There are advantages in Carden's identification of the two terms, notably the attention which it focuses on the links between Modernism in literature and in the other arts in Russia in the first quarter of the century. In the early work of the painters Goncharova, Larionov and Kandinskii, and the composer Stravinskii, Carden sees "a mood and style reminiscent of ornamental prose," the common features being "a folkloristic primitivism of subject and mood" and "a display of artistic virtuosity" (Carden, "Ornamentalism and Modernism," p. 49). Although this insight into the unifying elements of Modernism in the Russian arts is productive, it serves to narrow the scope of literary Modernism by restricting it to the work of writers who exhibit precisely this combination of folkloric primitivism and formal experimentation. While some of Zamiatin's stories would be covered by this definition, the folkloric elements (though not the primitivism) are absent in We. And authors from a slightly later period, such as Olesha, would be considered by most critics to be modernist, although far removed from the ornamentalism of Remizov or Pilniak.

Several significant novels of the 1920s and early 1930s raise the issue of the boundaries of Modernism in Russian literature: can a work be modernist by virtue of experimental form alone, or does Modernism imply a sensibility marked by uncertainty and instability? The question is made more difficult by the chaotic and paradoxical nature of the period - that of the Revolution and Civil War - in which many Russian novels of the 1920s are set. When Pilniak reflects the political, social, and moral uncertainties of the year 1919 in the chaotic canvas of The Naked Year, when Konstantin Fedin uses a convoluted chronological structure to suggest the complications of the period between 1914 and 1922 in his Cities and Years (1924), or when Isaac Babel depicts the Cossack campaign in Poland in 1920 in a series of interrelated short stories that shock and thrill through the juxtaposition of ethical and aesthetic opposites (Red Cavalry, 192.6), are the chaos and instability an inherent part of the subject-matter, or are they indications of a modernist sensibility in the authors concerned? There is no comprehensive answer to this question. Many major authors of the 1920s attempted to find formal, aesthetic equivalents of the massive social and moral upheaval of the age, but if Babel's prose, for example, is undoubtedly modernist, Fedin's is essentially traditional, with its roots in the Western nineteenth-century realistic novel and a hero, Andrei Startsov, who is the direct descendent of the superfluous men of an earlier period of Russian Realism. The experimental form of Cities and Years derives less from a modernist sensibility than from Fedin's interest in the story-telling possibilities of the Western novelistic tradition which he and other members of

the Serapion Brothers felt were absent in the Russian novel, as well as from the structural possibilities suggested by the new art of the cinema. It is one of several prose works of the period given a modernist veneer by the desire to convey some of the excitement and suspense of the adventure novel or of narrative film.

Nowhere can this tendency be seen more clearly than in the early novels of Valentin Kataev, particularly the much underrated Time, Forward! (1932). In 1936 Kataev wrote: "The elements of cinematic montage, the very concept of montage became organic for many writers of my generation. . . . Time, Forward! is a work constructed literally on cinematic principles."19 Yet, in contrast to some of Kataev's disturbing late works published between 1965 and his death in 1986, the Modernism of Time, Forward! is one of form rather than spirit. Despite its emphasis on movement, the novel promotes stability, combining the formal experimentation of the 1920s with the new political certainties of the Stalinist period.

A more secure place in the Russian modernist canon is occupied by Yurii Olesha's Envy (1927), a novel which bears a formal resemblance to Notes from Underground. The sense of alienation and existential anxiety experienced by the protagonist, Nikolai Kavalerov, may be linked with the general alienation of the "little man" in Russian literature from Pushkin onward, and, more specifically, with the theme of the "vacillating intellectual" that featured prominently in works of the 1920s. Unable to commit himself to the detested new regime to which he feels superior, and afraid that in its reliance on reason and technology it will shun his essentially emotional and impressionistic apprehension of the world, Kavalerov feels painfully isolated and deprived of a sense of belonging. His ambivalent response to the new world of Soviet society, which he both despises for its supposed lack of humanity and envies because of its vigor and purposefulness, is typical of the heroes of a number of novels in the 1920s, including Andrei Startsov in Cities and Years. But unlike other works with a similar hero, Envy transcends the topical concerns of post-revolutionary Russia by focusing on the relationship between the observer and the material world, and in this respect it is located in one of the mainstreams of European Modernism. Olesha's concern is frequently with the nature of objects and the defamiliarizing effect of such optical tricks as magnification, miniaturization, reflection, refraction, and observation from unusual angles. Kava-lerov's precise and detailed, yet personal, observation of the world around him is reminiscent of the literary Impressionism of Proust and other French writers. When the sharpness of vision is allied to Kavalerov's seemingly endless cascade of unusual and provocative metaphors, the essence of Olesha's modernist prose emerges: fresh, idiosyncratic observation of the

surrounding world combined with metaphor that simultaneously renders the physical reality of the object for the reader and illuminates the psychology of the protagonist/observer.

In his 1992. book Utrachennye al'ternativy (Lost Alternatives), M. M. Golubkov examines the "aesthetic pluralism" of Russian literary theory and practice in the 1920s and shows how, largely as the result of political pressure, Realism, which was simply one aesthetic trend among several, came to be canonized as the only acceptable method for Soviet literature of the 1930s and later decades. The "cultural polycentrism" of the 1920s was replaced by a "monistic" or "monophonie" culture in 1934, and the various modernist trends that had contributed to making the 1920s one of the most interesting periods in the history of Russian literature became nothing more than the "lost alternatives" of Golubkov's title.20 This analysis of the Russian literary process in the 1920s and early 1930s is hardly original (it has been the standard Western interpretation for many years),21 but Golubkov's examination of the various branches of modernist prose of the period is of considerable interest. As elsewhere in Europe at this time, the two major divisions of modernist poetics were Impressionism and Expressionism, the former marked by a subjective and hence psychologically significant apprehension of the physical world, and the latter by grotesque deformations, and the absence of individual psychology. The distinctiveness of Russian Modernism, however, lies in the fact that Impressionism and Expressionism are rarely juxtaposed as opposites. Instead, elements of both aesthetic systems are frequently to be found in the same work. Thus, while Expressionism can be most clearly seen in anti-utopian novels such as Zamiatin's We and Andrei Platonov's Chevengur (completed in 1929) and The Foundation Pit (1930), some of its elements can be found in the work of many novelists of the 1920s, such as Gorkii, Kaverin, Tynianov, Bulgakov, and Olesha, who could not adequately be defined as Expressionists. Olesha's debt to Proust might suggest that Envy can be categorized as a work of literary Impressionism, yet in some respects such as the presentation of Andrei Babichev and the starkness of the conflict, with the characters drawn up in opposing camps, its expressionistic elements are strong.

Platonov's The Foundation Pit is one of the major works of Russian Modernism, a grotesque, expressionist vision of the Utopian myths of the first Five-Year Plan period and at the same time an ontological discourse on the relationship between existential essence, flesh, and language. The 1920s saw a widening of the boundaries of literary language in Russia. In itself, skaz - the narration of a text in part or in whole through the substandard speech of an uneducated and sometimes morally obtuse narrator - was not

new (Leskov in particular had used it to great effect in the nineteenth century), but in the 1920s it became very common. The satirical short stories of Zoshchenko and some of Babel's Red Cavalry stories are among the best examples. The incorrect use of "officialese" by semi-literate workers and peasants was also a feature of some works of the 1920s (for example, one of Pilniak's characters uses the memorable phrase enegrichno fuktsirovat' - "to fuction enegretically," meaning, presumably, "to function energetically"). But even in a period of linguistic experimentation and eclecticism, the language of Platonov's tales and novels (which Joseph Brodsky described as "untranslatable")22 is unusually striking. It appears to arise from a confrontation between the colloquial language of the newly and as yet incompletely literate peasants and workers on the one hand and the grandiloquent, slogan-laden "Sovietese" of official publitsistika on the other. Disconcertingly, this awkward fusion of linguistic elements is addressed repeatedly to ontological questions. The narrative stance is stubbornly materialistic. Platonov's narrators, their mentality formed by the militant materialism of the 1920s and early 1930s, make no distinction between abstract and concrete, animate and inanimate. Thus, nouns denoting inanimate objects are frequently combined with "inappropriate" adjectives and verbs denoting feelings. In addition, prepositions and cases are used in an unexpected fashion so as to draw attention to particular details. The effect can be strangely disorientating. Here, for example, is a typical extract, taken from the opening pages of The Foundation Pit:

Voshchev grabbed his bag and set off into the night. The questioning sky shone over Voshchev with the agonizing strength of the stars, but in the city the lights had already been extinguished: whoever was able to do so was sleeping, having eaten his fill of supper. Voshchev descended the crumbly earth [po kroshkam zemli] into a ravine and lay belly-down, so as to fall asleep and part from self. But for sleep, peace of mind was necessary, its trustfulness in life, forgiveness of experienced grief, and Voshchev lay in the dry intensity of consciousness and did not know whether he was useful in the world or whether everything would manage well without him. From an unknown place a wind began to blow, so that people should not suffocate, and in a weak voice of doubt a suburban dog made known its service.

A strong streak of fantasy, with its roots in Gogol and in Dostoevskii's "realism in a higher sense," is characteristic of many of the most significant modernist novels in Russia, including Petersburg, We, and The Foundation Pit. One of the characters in Platonov's novel is a proletarian "blacksmith-bear" who wages a particularly ferocious class war against kulaks. He is presented as a real bear and at the same time a real blacksmith, and his

origins seem to lie simultaneously in folklore and in the realization of a metaphor (native Russian strongman = bear) that is so deeply embedded that it scarcely affects the reader's perception of the bear's animal status. Apart from We, however, the most celebrated example of fantasy in the Russian modernist novel is that of Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita (1928-40), in which farcical comedy coexists with high seriousness, mundane reality with supernatural interventions, twentieth-century Moscow with first-century Jerusalem. Bulgakov's text moves freely in time and space, in the realms of the real and the fantastic, and in matching stylistic registers in a manner that anticipates the "magic realism" of a later era. Some of the principal features of the modernist novel are clearly present here, notably the initially bewildering heterogeneity of the material, the free handling of time and space, and the prominence of the irrational and fantastic. Yet although the novel has a strong apocalyptic element, it lacks the nervous, edgy tenor of much Russian modernist fiction. Its foregrounding of the theme of ultimate justice is reassuring in a way that runs counter to the anxiety and uncertainty of modernity.

Among the many themes of The Master and Margarita is one which is particularly relevant to the modernist novel as a whole: the nature of fiction itself and the status of the fictional text. Most major Russian modernist novels are concerned to some extent with the creative process itself. The precise nature of the diary and the full implications of the act of writing in We, and the relationship between the Master's novel, the authorial novel, and "real" events in The Master and Margarita are but two examples of this concern.

Of course, one must be careful not to imply that metafiction is inherently modernist; fiction about the creation of fiction has existed throughout the ages, and was particularly prominent in the Romantic period. In the age of Modernism and subsequently postmodernism, though, a strikingly high proportion of literary texts are metafictional. In addition to those already mentioned, the novels of Vladimir Nabokov are perhaps the prime example, and it is no coincidence that Nabokov's influence may be detected in the work of several of Russia's postmodernist writers of the present generation, such as Viktor Erofeev and Andrei Bitov. For Erofeev in particular, the aesthetic lessons of the modernist period are very important for the future of Russian literature. In his influential article "Soviet literature: In memoriam," published in 1990, he draws attention to the huge extraliterary weight traditionally attached to creative writing in Russia. It was never enough, he reminds us, for a writer to be simply a writer; under Tsars and Soviets alike he or she had also to fulfil one or more of the roles of mystic, prosecutor, sociologist, and economist, and this

extraliterary burden was frequently borne at the expense of the more properly literary aspects of the writer's craft: "while [the writer] was busy being everything else, he was least of all a writer."23 Attention to the social, political, or philosophical "message" frequently displaced attention to style, to the precise nuances of literary language. Erofeev expresses the hope that Russian writers will shake off their obsession with society and turn inwards to the proper, wholly aesthetic concerns of art, and that literature will become self-sufficient and self-justifying in a way it had rarely done in the past.

Given the chronological boundaries of Modernism adopted earlier (from the 1890s to the 1930s), detailed consideration of the work of Erofeev, Bitov, Sasha Sokolov, and other writers of the late Soviet and post-Soviet period is beyond the scope of this chapter. It is worth noting, though, that the legacy of Modernism is to be seen almost everywhere in serious contemporary Russian fiction. The dazzling artfulness and intertextuality of Bitov's Pushkin House (1978); the surrealism of Sokolov; the use of the grotesque by writers such as Liudmila Petrushevskaia, Viktor Pelevin, and Vladimir Sorokin; and the highly volatile, identity-questioning prose of Valeriia Narbikova - these and other aspects of contemporary literature owe much to the tradition of the Russian modernist novel.

NOTES

1. V. Erlich, Modernism and Revolution: Russian Literature in Transition (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994), p. 1.

2. M. Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983).

3. The Marquis de Custine quoted in Donald Fänger, Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism: A Study of Dostoevsky in Relation to Balzac, Dickens and Gogol (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1967), p. 105.

4. See Fänger, Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism, p. 1x9.

5. On this point see M. Holquist, Dostoevsky and the Novel (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1986), p. 36.

6. Grossman is quoted in Fänger, Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism, p. 129.

7. On this point see R. Maguire and J. Malmstad, "Translators' introduction," in Andrei Bely, Petersburg, trans, and intro. R. Maguire and J. Malmstad (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978), p. vii.

8. E. Zamiatin, "Zavtra," in Zamiatin, Sochineniia, 4 vols. (Munich: Neimanis, 1970-88), vol. IV, pp. 246-47 (p. 246).

9. E. Zamiatin, "Skify li?" ("Scythians?"), in Zamiatin, Sochineniia, vol. IV, pp. 503-13 (p. 503).

10. E. Zamiatin, "O literature, revoliutsii i entropii" ("On literature, revolution and entropy"), in Zamiatin, Sochineniia, vol. IV, pp. 291-97 (p. 291).

11. Ibid., p. 293.

12. Ibid, p. 296.

13- E. Zamiatin, "? sintetizme" ("On synthetism") in Zamiatin, Sochineniia, vol. IV, pp. 282-90 (pp. 282-83).

14. On Zamiatin and Nietzsche see Peter Doyle, "Zamyatin's philosophy, humanism, and We: a critical appraisal," Renaissance and Modern Studies, 28 (1984), 1-17.

15. On Zamiatin's artistic indebtedness to Gogol and Dostoevskii, and on the nineteenth-century writers as progenitors of Russian Modernism, see Susan Layton, "Zamyatin and literary modernism," in Gary Kern (ed.), Zamyatin's "We": A Collection of Critical Essays (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1988), pp. 140-48, especially pp. 146-47.

16. See Carl Proffer, "Notes on the imagery in Zamyatin's We," in Kern, pp. 95-105; Alex M. Shane, The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), p. 158; Christopher Collins, Evgenij Zamjatin: An Interpretive Study (The Hague: Mouton, 1973), p. 53.

17. Sona S. Hoisington and Lynn Imbery, "Zamjatin's modernist palette: colors and their function in We," Slavic and East European Journal, 36 (1992), 159-71.

18. For a critical modern appraisal of Pilniak see Patricia Carden, "Ornamentalism and Modernism," in George Gibian and H. W. Tjalsma (eds.), Russian Modernism: Culture and the Avant-Garde, 1900-1930 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1976), pp. 49-64.

19. V. Kataev, "Rovesniki kino," in Kataev, Sobranie sochinenii, 9 vols. (Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1968-72), vol. VIII (1971), p. 314.

20. M. M. Golubkov, Utrachennye al'ternativy (Moscow: Nasledie, 1992).

21. For a somewhat different view see Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism, translated by Charles Rougle (Princeton University Press, 1992).

22. I. Brodskii, "Predislovie," in A. Platonov, Kotlovan (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1979), p. 7.

23. Viktor Erofeev, "Pominki po sovetskoi literature," Literaturnaia gazeta (4 July 1990).

4

STRUCTURES AND READINGS

12

ROBERT BELKNAP

Novelistic technique

The power of the Russian nineteenth-century novel depends in part on earlier techniques of novel-writing which most Western novelists had abandoned. This study will concentrate on the particularly Russian relation between plotting and narration, though it must also reckon with the interplay between Russian and the Western novelistic practices in the nineteenth century. In the first Western book on the Russian novel (1881), Melchoir de Vogué, the eloquent French diplomat, journalist, and gossip, says that for Turgenev the study "of our masters and the friendship and the advice of Mérimée offered precious help; to these literary associations he may have owed the intellectual discipline, the clarity, the precision, virtues which are so rare among the prose writers of his country."1 This denial that Turgenev is a fully Russian novelist shows that Vogué recognized something special about Turgenev, but it also led Western Europeans from the 1880s on to recognize that there was something special about most Russian novels. A generation later, Henry James praised the power and richness of the Russian novels, but his letter to Hugh Walpole called them "fluid puddings," and he complained to Mrs. Humphry Ward about Tolstoi's "promiscuous shifting of viewpoint and centre,"2 perhaps reflecting de Vogue's description of what he felt on reading Dostoevskii, "the shiver that seizes you on encountering some of his characters makes one wonder whether one is in the presence of genius, but one quickly remembers that genius in letters does not exist without two higher gifts, measure and universality …" (de Vogué, Le Roman russe, p. 267). James's prefaces contain the first and most subtle exposition of the novelistic techniques that evolved in the West in the nineteenth century, and his novels may be the least provincial ever written; and yet, somehow, he failed to realize that the rules he presented were not universal aspects of the psychology of art but the conventions of a particular time and place. The Russian interdependence between plotting and narration constituted a very different but no less demanding kind of technical mastery, as can be seen in The Brothers

Karamazov (1880) by looking at the tight relationship between the spiritual state of the character being discussed and the presence or absence of omniscience in the character discussing him. Many Western critics distinguish novels that tell readers what happens from novels that show them what happens; the Russian novelistic techniques let Tolstoi, Dostoevskii, and others go beyond both these practices and manipulate readers into experiencing for themselves what the characters in the novel are feeling and arguing.

The Russians inherited this literary goal from Rousseau, Sterne and the other sentimental novelists of the eighteenth century. The Russian Formalist literary critics distinguish between two kinds of literary plot, both of which fit the old definition of a plot as the arrangement of the incidents. In the first kind of plot, or the fabula, the incidents are arranged in the world where the characters live, so that in the fabula a character is always born before dying. In the second kind of plot, or siuzbet, the same incidents are arranged in the text, where the death of a character may be presented long before the birth. All novels rely heavily on the interplay between these two kinds of relationship among incidents, but the nineteenth-century Western novel centers on the relation between the fabula and character, with characters shaping and responding to the sequence of events. In many eighteenth-century and Russian nineteenth-century novels, the siuzbet plays a more important role, and has a closer relation to those crucial figures in all novels through whom we perceive everything else, the narrators. Novels in letters flourished in the eighteenth century partly because collections of real letters and manuals for letter-writing were popular, but also because letters enable authors to trace different careers through the same sequences of incidents and to triangulate a given incident through several sets of responses, so that narration interacts very closely with plot. Russians wrote only half a dozen letter novels in the eighteenth century and only one memorable one in the nineteenth century, Dostoevskii's Poor Folk (1846); yet even a markedly Russian novel like War and Peace shows Tolstoi's often-mentioned eighteenth-century mentality in the interwoven plotting that uses the lives and consciousnesses of several characters and a chameleon-like narrator to infect readers with Tolstoi's historical, psychological, and moral awarenesses.

Nikolai Karamzin (1766-1826) was the chief early conduit carrying this eighteenth-century tradition from the West into Russian nineteenth-century prose. Karamzin's most famous short story, "Poor Liza" (1792), appealed to the sentiment that expresses itself through tears, but the sentimentalist aesthetic also valorizes the emotions that produce laughter, social action, and many other responses. In Karamzin's "My Confession" (1802), the

narrator prides himself on his lack of honor, sanity, and social value, carrying Rousseau's wilful taboo-breaking and gratuitous actions to a level of insulting self-consciousness that bridges the gap between Rousseau's voice in his "Confessions" and that of Dostoevskii's Underground Man.

In his role of follower, competitor, and successor to Karamzin as the central figure on the Russian literary scene, Pushkin seems at first to belong to the Western nineteenth-century novelistic tradition, as Turgenev did in his major novels, and as did many lesser novelists in Pushkin's generation, such as Senkovskii, Polevoi, Marlinskii, Bulgarin, Pogorelskii, Lazhech-nikov, Veltman, or Zagoskin. Certainly Pushkin loved the fashionable and was drenched in Western literature; his Captain's Daughter (1836) draws its setting and much of its plot from Sir Walter Scott's Waverley. Yet the works of Pushkin that most influenced the later Russian novels were not conventional novels at all. One was Evgenii Onegin (1823-31), a novel in verse, and the other was The Tales of Belkin (1830), which are usually treated as a group of separate stories. The plotting in Onegin follows the standard pattern René Girard ascribes to European novels: desire is imitative and unreciprocated.3 Onegin rejects Tatiana's love until he sees her loved, and she rejects him when he offers himself to her. But in both of these works, the narrator stands back and reflects upon the incidents in ways that seem sometimes naive and sometimes remarkably sophisticated. The narrator of Evgenii Onegin cries out "Alas!" like a sentimental novelist, and digresses like Fielding or Sterne, although he also enters with the reader into conspiratorial judgment of his hero in the manner of Scott or later, Dickens and Thackeray. Pushkin may draw his plots from contemporary Europe, but his narrative technique in Onegin retains much of Sterne's or Fielding's or Voltaire's eighteenth-century flexibility and playfulness, with a "preface" at the end of chapter 7 and the siuzhet containing much detail about the life and opinions of the narrator which plays no part in the lives of the characters at all.

The Tales of Belkin fall midway through the evolution of the most ambitious Russian prose in the 1820s and 1830s as it recapitulated the long and intricate history of the proto-novel in Europe, moving from collections of individual tales, like Karamzin's, or the Gesta Romanorum (?. 1300), to tales linked by a narrative situation, like Marlinskii's Evenings on the Bivouac (1823) or Boccaccio's Decamaron (1360s), through tales linked by a single narrator like Belkin or Malory's narrator (1485), to tales linked by a single hero, like Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time (1841) or Don Quixote (1605, 1615). Such evolution never occurs neatly; early techniques often attract late writers more than prescient recent works of isolated geniuses, but the Russians were able to do in decades what took centuries

in the West precisely because in addition to the classical sources in epic, romance, Petronius, Apuleius, and others which shaped the Western novel, the Russians had an existing novelistic tradition developed by Emin, Chulkov, and others in the eighteenth century, and, far more important, the rich novelistic tradition of the West to draw on. Belkin breaks Henry James's cardinal rule for a narrator. James's narrators may be wise or foolish, even insane or fanatic, but must be consistently whatever they are, so that "the interest created, and the expression of that interest, are things kept, as to kind, genuine and true to themselves." Moreover, narrators who can see into a character's mind at one moment must not learn what that character is thinking from his countenance at another moment.4 The introduction to The Tales of Belkin states that Belkin died at the age of thirty, while on the first page of "The Station Master," Belkin states that he has been travelling through Russia steadily for twenty years. More important, Belkin begins telling "The Blizzard" with full insight into the mind of the heroine and suddenly switches to the narration of her actions entirely from outside. Pushkin breaks James's rules here not through ignorance or inattention, but simply because other literary needs precluded obedience to such rules. The effectiveness of the siuzhet demanded that the reader share Maria's bookish but wholehearted love and also her surprise at the ending of the story. Consistency would have cost him one or the other of these effects, and Pushkin therefore turns to the eighteenth-century tradition of more flexible narrators.

Like The Captain's Daughter, Lermontov's first novel, Vadim (1834), draws heavily on Walter Scott for its plot and atmosphere, and his A Hero of Our Time was the only Russian novel in the first half of the nineteenth century to be judged so accessible to the West that it was repeatedly translated into French. Yet for all its accessibility to Europeans and debts to Scott, Byron, Musset, George Sand, and others, the intricate interplay between its plot and narration sets A Hero of Our Time apart from the mainstream Western novels and other narratives of its time. As the arrangement of events in the world the characters inhabit, the fabula of A Hero of Our Time has an identity whose complexity rivals and intersects that of the narration. Narratively, the voices of Bela, Grushnitskii, or Princess Mary reach the reader through the accounts of Maksim Mak-simych or Pechorin, which are filtered through the voice of an "editor" who sometimes selects the materials from "a thick notebook," and always edits at least the names to protect the real people portrayed. And from the 1841 edition on, a preface interposes the outermost voice of an authorial figure who knows that all the others are fictional. Such narrative layering was commonplace in Russia and the West in the 1830s, but these different

figures inhabit very different worlds, knowing about different events, and more importantly, seeing totally different mechanisms as organizing these events.

In any novel, the central organizing principle in the fabula is usually cause and effect, or its psychological reflex, motivation, but A Hero of Our Time also takes the form of a philosophical dialogue on the nature of causality. On the first page of the novel, the "editor" introduces the topic with a question that applies a certain causal system naively, "How is it that four oxen can haul your loaded carriage like a lark, and six of the creatures can scarcely budge my empty one with the help of these Ossetians [inhabitants of the Northern Caucasus]?" This editor's world operates by the laws of physics, or, when he predicts a fine morrow, by appearances. Maksim Maksimych operates in a world of hidden causes, explaining how the Ossetian greed for extra business makes them impede their own oxen, or how the steam rising from a distant mountain presages a blizzard. Though he is the central figure, Pechorin is only a minor narrator in this first story, but he introduces a Byronic system of motivation into a story where Bela, Kazbich, and the other characters have motives out of a Walter Scott novel, "Listen, Maksim Maksimych … I have an unhappy character: whether my upbringing made me so, or God made me so, I don't know; I know only that if I am the cause of unhappiness to others, I am no less unhappy."5 Maksim Maksimych is as naive about such Byronism as the "editor" is about the Caucasus: "'Did the French bring boredom into fashion?' - 'No, the English.' - 'Aha, that's it … of course, they always were outrageous drunkards'" (p. 2.14). Maksim Maksimych introduces not only ethnic, economic, atmospheric, and alcoholic determinism into the causal system; he also uses social class to explain behavior: "What are we uneducated oldsters doing, chasing after you? . . . You're young society folk, proud; as long as you're here under the Cherkassian bullets, you're OK . . . but if you meet us afterwards you're ashamed to offer your hand to one of us" (p. 228).

Maksim Maksimych's causes relate events to one another in the realistic tradition, contrasting not only with the physical causality the editor espouses, but also with the Romantic kinds of causes Pechorin invokes: "These eyes, it seemed, were endowed with some magnetic power' (p. 235); "the bumps on his skull . . . would have astonished a phrenologist with the strange mix of conflicting drives" (p. 248); "We're reading one another in the heart" (p. 249), and so on. For the future of the Russian novel, more important than such phrases are four specially Russian features of causation in Pechorin's accounts: coincidence, including all Pechorin's accidental eavesdropping; the sovereign power of the will, as when Pechorin

draws a group of listeners away from other entertaining interlocutors, or makes Grushnitskii miss his shot; the gratuitous actions, motivated not by anything external but by the nature of the character, such as that which makes Pechorin wonder "why did I not want to set out on that path fate had opened to me where quiet joys and heartfelt calm awaited me? . . . No, I should never have adapted to that destiny" (p. 31z); and finally, fate, which he discusses throughout, but most especially in the final story.

The complex of Pechorinesque causations never exists alone because his narrative voice never exists alone any more than Onegin's does. At the end of the novel, Maksim Maksimych initially responds to Pechorin's account of an experiment in Russian roulette that appeared to confirm predestination: "Yes sir, It's a rather tricky matter! . . . Still, these Asiatic triggers often misfire, if they're badly oiled . . ." Here, the novel seems to have two fabulas, one organizing events according to the rules of practical life and another according to the more exciting rules of Pechorin's world. Lermontov gives Pechorin the last word about fatalism, but it is a curiously indecisive comment on the entire panoply of causal systems that this novel explores in its plot and narration: "[Maksim Maksimych] in general dislikes metaphysical debates."

Lermontov certainly popularized Rousseauesque and Byronic motivational systems that the Russians went on using in close conjunction with their narrative techniques, but the chief explanation for the differences between the Western and the Russian novels of the nineteenth century can be expressed in two words: Nikolai Gogol. Like Karamzin, Gogol has been called the Russian Sterne. It has been argued that the Western Europeans drew a new kind of novel from the tradition of Scott and the "Gothic" novelists because Sterne had carried so many eighteenth-century novelistic techniques to the point of absurdity. The Russians also drew heavily on the sensationalism of Hoffmann and the Gothic novels coupled with the sharp social, moral, and psychological judgment of Scott's novels. Gogol's first novel, Taras Bulba (1835), owes much to Scott; yet Gogol also enabled the Russians to go on developing the techniques of the eighteenth-century Western novels they had been reading in translation and in the original for generations. A short story that appeared almost simultaneously with A Hero of Our Time gives the clearest illustration of Gogol's departure from the Western European tradition later canonized in Henry James's prefaces.

"The Tale of how Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich" (1835) seems at first to be an almost plotless story of provincial pettiness, anger, and stupidity; two old friends quarrel over an insignificant request and go through their whole lives unreconciled. In the first sentences of the story, the narrator seems to be equally involved in the insignificant: "Ivan

Ivanovich has a glorious jacket! The most excellent! And what lambswool! Whew, go to, what lambswool! I'll wager Lord knows what if you find anybody's like it!" These words give little information about Ivan Ivanovich but a great deal about the narrator. He is still close enough to infancy to love fuzz, to end every phrase with an exclamation point, and to bubble over with enthusiasm at matters that most of us might at most consider nice. Three pages later, this narrator remains enthusiastic and naive, but already has acquired enough control of himself and the world to enter into sociological, statistical, and perhaps biological disputation:

It has been spread around that Ivan Nikiforovich was born with a tail at his back. But this canard is so absurd and at the same time stupid and indecent that I judge it unnecessary to refute before enlightened readers, who are aware without the slightest doubt, that only witches, and even very few of them have tails at their backs; and they, moreover, belong for the most part to the female sex rather than the male.6

Whatever our views on the statistics of caudal preponderance, we all can recognize a much more mature voice than that of the narrator at the beginning of the story. When he appears again twenty pages later, this narrator has developed the voice of a jaded traveler with a clear and ironic sense of the Russian bureaucracy: "The trial then moved with that uncommon speed for which our judiciary is so commonly renowned. They annotated papers, excerpted them, numbered them, bound them, and receipted them all on one and the same day, and placed it all in a cabinet where it lay, lay, lay, a year, another, a third . . ." (vol. n, p. 2.63). And a few pages later, the narrator has even acquired literary self-consciousness: "No, I cannot! . . . Give me another pen! My pen is faded, deadened, with too thin a stroke for this picture!" (p. 271). Finally, on the last two pages of the story, a conscientious, self-important, tired old man displays no trace of enthusiasm:

At that time the weather exercised a strong effect on me: I grew bored when it was boring … I sighed still more deeply and hurried to make my adieus because I was traveling on a quite important matter, and got into my carriage . . . It's boring on this earth, Gentlemen! (pp. 275-6)

This final exclamation point has nothing in common with those at the beginning of the story. These last words almost coincide with Winston Churchill's to his son-in-law while dying in his tenth decade.7 Henry James would consider this changing narrator loose and baggy, a danger to the reliability that rests on the integrity of the figure through whom the reader must apprehend everything in the text. And yet Gogol orders these changes

tightly. His narrator has rather more of a career than any other character in the story. Readers see the growing decrepitude and pointlessness of the officials, the provincial town and the two Ivans, and without noticing it, they also experience the ageing of the narrator, and his unsuccessful struggle against the pointlessness of his existence. By breaking the narrative rules of the West and giving his narrator a plot of his own, Gogol implicated the reader in the ageing process that is going on all around him.

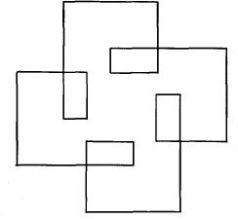

Gogol's Dead Souls (1842) became the most important force in the evolution of the Russian technique of novel-writing well before the novel gained recognition from thousands of bemused readers on the world scene. The fabula of the novel derives in large part from that of the typical romance of the road in which a picaro or a more highly placed scamp moves from place to place and extricates himself from scrape after scrape in separate adventures whose organization some critics compare to that of beads on a string. In the manner of Cervantes and Fielding, the siuzhet of Dead Souls contains digressions, responses to real and imaginary readers, and appeals to the reader's experience which are usually not a part of the world the characters inhabit. In one such digression in the last chapter, the narrator apologizes for the far from exemplary characters who have appeared in part I of the novel: "This is Chichikov's fault; in this he is full master and we must be dragged after him wherever he takes it into his head to go" (Gogol', Polnoe sobraniie sochinenii, vol. vi, p. 2.41). In part, this passage continues the playful mockery of verisimilitude that Gogol learned from Sterne and many others: "Although the time in whose duration they would traverse the hall, the anteroom, and the dining room is a bit on the short side, we will try and see whether we can use it somehow to say something about the master of the house" (vol. vi, p. 23). But blaming his hero for the fabula also rejects the idea of a structured plot with a beginning, a middle and an end, confirming the image of beads on a string. Aristotle defined an end as something which needs nothing after it to complete it, but if Sterne and Lermontov had lived longer, Tristram Shandy and A Hero of Our Time would probably have been longer, and Gogol actually wrote further chapters of Dead Souls, which he destroyed; one can always add another bead to a string. With such texts, structural analysis, based on a spatial metaphor in two or three dimensions, may be less useful than algorithmic analysis, based on a metaphor in a single sequence, like time, even though either system of reasoning can be made to work. The diagram on the next page can be described spatially, as a square with helically oriented inflected oblongs and similarly oriented smaller inset oblongs; sufficient measurements would enable a careful reader to reproduce the figure, but it is much easier to use an algorithm or a procedure in time:

Draw a line one unit long; turn left 90 degrees and draw a line two units long; turn left again and draw a line three units long; turn left again and draw a line four units long; turn left again and draw a line five units long; start over. In this procedure, the action at each step is a reaction to the situation after the last step rather than to a vision of the whole. But because it follows explicit rules, it produces a coherent whole. In fiction, a procedure can produce as elegant and powerful an experience as a structural plan can, but it looks loose and baggy to a nineteenth-century Western sensibility.

In Dead Souls, Gogol's rules are accretive and perverse. He adds and adds and adds, and suddenly takes it all away. This pattern repeats itself fractally, at the level of the sentence, of the episode, and of the string of episodes. Chichikov and his two recalcitrant serfs move among landlords with recalcitrant stewards managing recalcitrant serfs, under the aegis of petty officials who cannot control them or be controlled by figures still higher in the fractal hierarchy. Fawning and greed shape the hierarchy at every level, whether the greed be for vodka or a great house, and the protestant virtue, deferral of gratification, exploits the first of these vices for the sake of the second. At each stage of Chichikov's career, in school, as a provincial bureaucrat, as a customs officer, and on his visits to the various town and landed figures, he displays extraordinary discipline until he makes his coup, at which point he loses all control, lets his greed prevail, and has to escape and start over. This pattern of moving from misery into a moment of seeming paradise, and then losing it runs through all of Gogol's best work. Most often, the paradise was never really there in the first place. In Sterne, the anticlimax makes the reader feel foolish or cheated: "Why

didn't I see that coming?" or "How could I be expected to know that?" In Gogol, the frustration of expectations grows out of the logic of a situation that always partakes of the weirdness of Russian life. His very sentences have plots, adding, adding, adding, and then suddenly taking away. The last sentence of chapter 6 offers a good example: "Requesting the lightest possible repast, consisting of nothing but pork, he immediately undressed, and curling up under the bedclothes, fell hard asleep, soundly, in wondrous fashion, as only those sleep who are so happy as to know neither hemorrhoids, nor lice, nor overly powerful mental capacities" (Gogol', Polnoe sobraniie sochinenii, vol. vi, p. 132). Stupidity is often praised, but Gogol finds a context for the praise that contrasts the experience of Chichikov with that of thousands of insomniacs who do not inhabit the world of the novel. Narration here too has a plot of its own.

Tolstoi and Dostoevskii carried the innovations of their Russian predecessors to their highest fruition. When James called War and Peace a "large loose baggy monster" like The Three Musketeers (1844), he failed to see it as a novel of ideas that programmed the reader's experience of those ideas with a mastery as disciplined and well-read as his own. Dostoevskii probably was the person who told de Vogué, "We all emerged from under Gogol's 'Overcoat'." In any case, he often recognized his debt to Pushkin and the two great "demons" in Russian literature, Lermontov and Gogol, as well as to Karamzin and the creators of the nineteenth-century novelistic form in the West, Scott, Hoffmann, Balzac, Dickens, Hugo, and "Gothic" novelists like Ann Radcliffe. Virtually all the important Russian novels in the nineteenth century were written during his lifetime, and his own career paralleled that of the Russian novel in his youth and shaped it in his maturity.

A highly self-conscious experimenter in and borrower of novelistic techniques, Dostoevskii began his career with a novel in letters, a form that had gone out with the eighteenth century. Poor Folk is a novel of oppression and compassion and also a variant on the eighteenth-century theme of the libertine who seduces a young girl. The variant comes from Karamzin's "Poor Liza" via Pushkin; Belkin's "The Station Master" had already explored what happens when the seduced girl so enthrals the seducer that he is reduced to marrying her and setting her up in splendor. Dostoevskii shows how the seducer struggles against this comeuppance and finally gives in to Varvara, though he is no great catch for her; she had lovingly nursed his son through a fatal illness and later reciprocated the love of the poor clerk Makar, who longed to starve with her. Dostoevskii's chief literary polemic, however, is with Gogol's "Overcoat," where the poor clerk starves and deprives himself to obtain a coat he needs, and then loses

it. Dostoevskii's story is about Makar's paradise lost, but Makar loses a human being and not a piece of cloth.

Dostoevskii's second novel, The Double (1846), has a plot that uses many techniques from the tales and novels of Gogol and of E. T. A. Hoffmann. His hero, the disintegrating clerk Goliadkin, has a series of experiences which can be explained as strange coincidences, practical jokes, supernatural events, or the delusions of a perception sinking into madness. Dostoevskii provides strong evidence for each of these plots and no basis for selecting among them, so that the cognitive dissonance drives the reader towards a disintegration very like Goliadkin's. In his major novels, Dostoevskii expands this technique.

In Crime and Punishment (1866), when Raskolnikov stands in the room with two bleeding corpses, holding his breath as he listens at the door, inches from his potential discoverers, who may leave or may bring the police, the readers hold their breath, exert their will upon him not to give up and confess, and then suddenly realize that they are accessories after the fact, trying to help this merciless hatchet-murderer to escape. This complicity in the crime alternates with the reader's horror and revulsion at it, just as Raskolnikov alternates between a drive towards murder and escape and a drive towards freedom from the murderous impulse and - after the murder - towards confession. Dostoevskii manipulates his readers into the plot of the novel by never letting them outside the mind of Raskolnikov, or briefly, the two surrogates who share different parts of his situation and react to it very differently, Razumikhin and Svidrigailov. This intensity of narrative concentration on a single figure implicates the readers in his predicament much as readers willed the escape of picaresque scamps in earlier novels. Crime and Punishment has a beginning, a middle and an end, but it retains the algorithmic integrity of Gogol and his masters. In Crime and Punishment, the shaping rule is not accretive and perverse as in Dead Souls, but rather the terrifying alternation between the crime and the punishment, the rational calculation that the destruction of a bloodsucking insect was an action worthy of a great man, and the direct, emotional realization that this was the blood of a helpless fellow human being. Dostoevskii uses his narrative tools to draw the reader inside this vacillation.

Readers have often charged Dostoevskii with undue reliance on coincidence in structuring the plot of the novel, and plainly, Raskolnikov's overhearing a conversation about murdering the old pawnbroker, like his overhearing a conversation indicating that she will be alone the next day, or his finding an axe on his way to commit the murder, all seem to remove his motives from the tight causal system that a proper Western novel would