The origins of Rus' (c. 900-1015)

JONATHAN SHEPARD

The Rus' Primary Chronicle's quest for the origins of Rus'

The question of the origins of Rus', how a 'land' of that name came into being and from what, has been asked almost since record-keeping began in the middle Dnieper region. The problem is formulated in virtually these terms at the beginning of the Rus' Primary Chronicle. The chronicle supposes a political hierarchy to have formed at a stroke, through a covenant between locals and outsiders. The Slavs, Finns and other natives of a land mass criss-crossed by great rivers agreed jointly to call in a ruler from overseas. Turning to 'the Varangians, to the Rus'' they said 'our land is vast and abundant, but there is no order in it. Come and reign as princes and have authority over us!'[1] The response, in the form of the arrival of three princely brothers with 'their kin' and 'all the Rus", is dated to around 862. The younger brothers soon died and the survivor, Riurik, joined their possessions to his own and assigned his men to the various 'towns' (grady). There were already 'aboriginal inhabitants' in them, 'in Novgorod, the Slovenes; in Polotsk, the Krivichi; in Beloozero, the Ves . . . And Riurik ruled over them all.' Before long a move was made southwards to the middle Dnieper by non-princely 'Varangians', Askold and Dir. They are said to have come upon a small town called Kiev and took charge, having learnt that the inhabitants paid tribute to the Khazars. Later a certain Oleg arrived, not, apparently, a prince himself, but acting on behalf of Riurik's infant son, Igor'. Denouncing Askold and Dir as 'neither princes, nor of princely stock', Oleg brought forth the child with the words 'Behold the son of Riurik!' and the two unlicensed venturers were put to death. The installation of princely rule in Kiev is dated around 882, with Oleg acting as Igor''s military commander.2

This sequence of tableaux was still being incorporated in works such as the chronicle of Nikon in the sixteenth century. They form the framework to any 'political' survey of the areas that would come to form part of Muscovy and, eventually, Russia. The Primary Chronicle's focus on princes can readily be dismissed as an oversimplification, a variant of European foundation myths involving two or three brothers. And the chronology sets developments both too early and too late. In reality, some sort of hegemonial structure already existed in the second quarter of the ninth century, perhaps earlier still, whereas the middle Dnieper only became a significant princely centre a generation or more after 882. Other qualifications could be made to the chronicle's picture, which is very much a product of the time when it neared completion, the opening years of the twelfth century, and also of the place - the Kievan Caves monastery. By then, the routes leading southwards along such rivers as the Volkhov and the Western Dvina to converge at the Dnieper and run down to the sea - 'the way from the Varangians to the Greeks' - formed an axis of obvious (though not unassailable) primacy The chroniclers' wishful assumption that power was from the first vested at points such as Novgorod and Kiev is understandable. They had little time for alternatives, such as routes from northerly regions to the Khazars based on the lower Volga and to the Islamic world. They note that people's rituals and customs across this 'vast' land had been variegated,3 but there are only occasional hints that princely authority itself might have been strung across several political centres through the ninth and most of the tenth centuries.

The vicissitudes of one leading family are treated as virtually synonymous with the emergence and extent of the land of Rus'. And yet in addressing the questions posed at the beginning of the chronicle - 'Whence came the land of Rus', who first began to rule as prince in Kiev . . .?'4 - the chroniclers did not play fast and loose with facts. Some places mentioned as centres of the 'Varangian' newcomers have been shown by excavations to have had Scandinavian occupants and visitors from the outset, for example Staraia Ladoga, while archaeology is uncovering important settlements started by 'aboriginal inhabitants' before the arrival of Scandinavians, for example, at Murom, Sarskoe and Pskov and a fortified settlement on the site of Izborsk. Other aspects of the chronicle's tableaux likewise gain corroboration from independent

2 PVL, p. 14.

3 The whereabouts and languages of different tribal groupings are described: PVL, pp. 10-11.

4 PVL, p. 7.

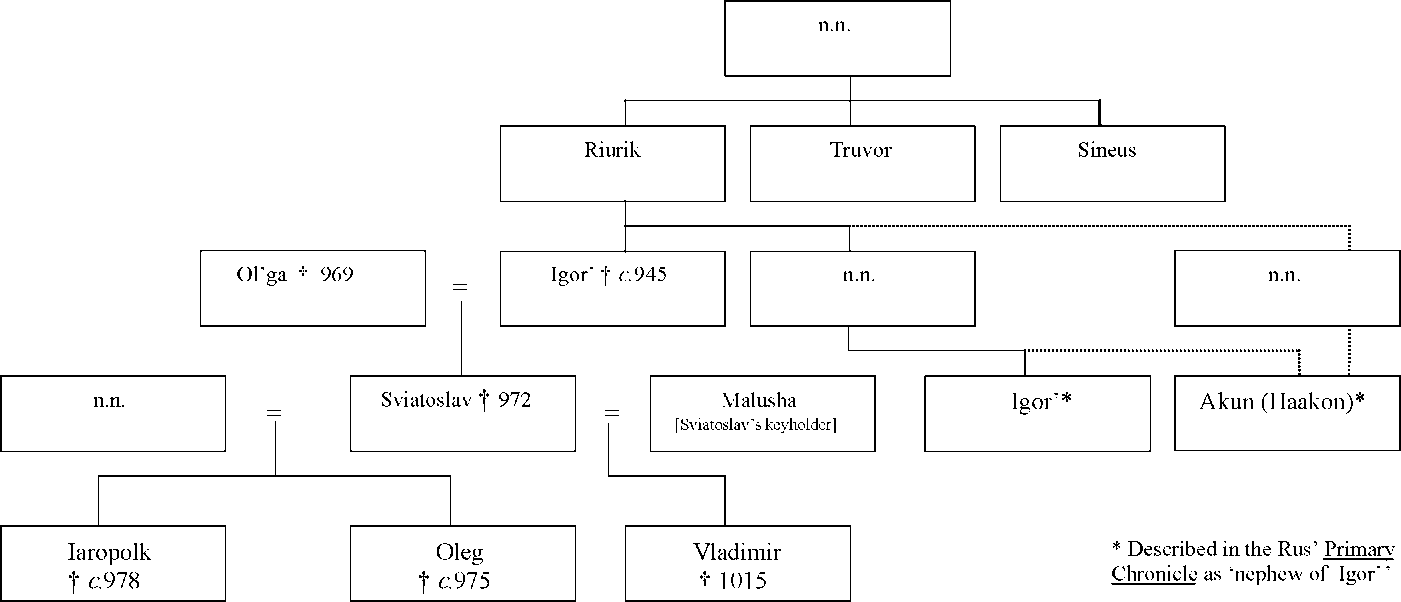

evidence. The princely line traced back in the chronicle was the most resilient and effective of whichever other ruling kin groups may have existed among the early Rus' (for the known descendants of Riurik, see Table 3.1). The name of the leading brother points clearly to an Old Norse original, *Hr0rikR, a form philologically plausible for the ninth century, when Riurik is supposed to have lived.[2] His son Igor' - the Slavic form of whose name harks back to Old Norse *Inghari - is an unquestionably historical figure. And for the final decade or so of the ninth century there is archaeological evidence of the establishment at Kiev of persons from much further north. Thus the Primary Chronicle registers actual political change and population movement under way in the late ninth century. But its composers drew from an exiguous database, spreading it thinly across gaps in their knowledge. Riurik is depicted as a commanding figure in the mid-ninth century, yet his son was active in the mid-tenth.[3] To gain an inkling of antecedents, one has to glance back to sources written far away and without first-hand knowledge, and to the oft equivocal findings of archaeology.

The beginnings of political formations

First signs of an organised power in the forest zone and of long-distance trading between the Muslim and Baltic worlds There had been a political hierarchy somewhere north of the middle Dnieper long before the turn of the ninth century, but it is hard to reconstruct the barest outlines. One firm fact is that by 838 there existed the ruler of a 'people' known to the Byzantines as Rhos and answering to that, or a very similar, name. Some Rhos accompanied a Byzantine embassy to the court of Louis the Pious, who was requested to assist them back to their 'homeland'.[4] The contemporary Frankish court annal relating this is carefully worded. It shows that the Rhos were well enough organised under a 'king' to send a mission to the Byzantine emperor, with sufficient resources for long-range embassies. The annal provides further clues about the strangers, clues at once suggestive and confusing. They described their own ruler as a chaganus, and when Louis investigated 'more diligently' he discovered that they 'belonged to the people

Table 3.1. Prince Riurik's known descendants

of the Swedes'. Fearing they might be spies, he detained them for further questioning. Thus their ruler bore a title akin to that of the ruler of the Khazars, the khagan, while their characteristics suggested those of 'Swedes'.

Countless historical interpretations revolve around this annalistic entry. There is no matrix against which to judge the inherent plausibility of one reconstruction against another. Much depends on assumptions about overall conditions between the Gulf of Finland and the Khazar-dominated Don and Volga steppes. But coexistence of a Scandinavian-led polity to the north with a Khazar power collecting tribute as far west as the Dnieper is the scenario implied in the Primary Chronicle. Objections can, of course, be raised: for example, to the discrepancy between the annal's intimation of a polity in 838 and the Primary Chronicle's chronology, and the sheer unlikelihood of a supposedly Swedish potentate assuming a Khazar title. There is, however, suggestive evidence of other Khazar and Turkic nomad traits in some of the Rus' elite's status symbols - for example the sporting of belts studded with metal mounts and ofbridles with elaborate sets ofornaments (see also below). Moreover, ambitious Scandinavian warlords in the British Isles were apt to take on local customs and Christian kingly attributes to bolster their regimes.

There are several reasons why Khazar styles of rulership and titles would have resonated among the inhabitants of major river basins north of the Black Sea steppes. This semi-nomadic people showed formidable organisational powers, regularly extracting resources from its neighbours, while the pax khazarica in the steppes between the Crimea and north-east of the Caspian Sea beckoned to traffickers along the 'Silk Roads' from the Far East, Caucasian markets and the core lands of the Abbasid caliphate. The abatement of Arab attempts to submit the Khazars and other steppe-dwellers to Islam, followed by the Abbasids' issue of huge quantities of silver dirhams from the mid-eighth century onwards, gave a fillip to trade nexuses of long standing. The dynamics of these exchanges are unknown to us and they fluctuated according to circumstances. But the predisposition of populations to cluster around lakes and along riverways provided staging posts and potential emporia for longer-distance traders. Great lakes such as Il'men' and Ladoga performed a dual function. Their resources and the fertile lakeside soils sustained sizeable concentrations of persons engaged in hunting, fishing and agriculture with iron ploughs. But they also acted as communications hubs, drawing in miscellaneous groups and individuals and enabling them to practise craftsmanship and trade. The nexuses between fur-yielding northern regions, the peoples of the steppes and Sasanian Persian and Byzantine markets attested in the sixth and earlier seventh centuries were probably not obliterated by the first century of Arab conquests. Their persistence would account for the speed with which silver coins from Abbasid mints reached the Gulf of Finland. At the small trading-post of Staraia Ladoga, Abbasid coins occur in almost the earliest 'micro-horizon'; so does a set of smith's tools analogous to kits found in Scandinavia. Workshops welded knives by an apparently Scandinavian technique, produced nails and boat rivets and by the beginning of the ninth century, if not earlier, glass beads were being worked up. One of the earliest hoards of dirhams uncovered in Russia was deposited early in the ninth century beside the Gulf of Finland, just west of modern St Petersburg. On some, Scandinavian-type runes and Arabic characters are scratched while the name of 'Zacharias' is scratched in Greek on one dirham and others have Turkic runes, such as might have been acquired en route through the Khazar dominions.[5] These markings serve as a paradigm of the types of outsider then active in the fur trade. And it can hardly be coincidental that dirhams feature among grave goods in central Sweden from the end of the eighth century. The region of Sweden facing the Aland islands was known in medieval Swedish law codes as 'Rodhen' or 'Rodhs'. The Baltic Finns' designation for persons hailing from there, Rotsi, probably became attached to all Scandinavians whom they encountered. So did the version subsequently borrowed by the Slavs, Rus'. These Rotsi probably traded in smallish groups on their own account, but emporia east of the Baltic facilitated travel and exchange, while an overarching symbol of authority would have encouraged order. An overlord sporting the same title as the Khazar ruler's - through whose dominions the dirhams, mentioned above, passed - fitted the bill. There is thus some congruence between the Frankish annals' indication of a Scandinavian 'people' headed by a khagan and the chronicle's tale of the native peoples' covenant with 'Varangians'.

Signs of turbulence c.86o-c.8yi

The location of the principal base of the 'khagan of the Northmen' (as a Byzantine imperial letter of 871 termed him)[6] is controversial, but may well have looked onto Lake Il'men', just south of the later Novgorod. Fortified from the start and with outlying settlements dating from the beginning of the ninth century or earlier, this large settlement-cum-emporium dominated communications northwards to Ladoga, eastwards towards the Volga's headwaters, and south towards the Western Dvina. The island-like site of what is now called Riurikovo Gorodishche could well be the inspiration for Arabic descriptions of a huge boggy 'island', three days' journey wide, where 'the khaqan of the Rus' resided.[7] This is presumably where a Byzantine religious mission headed for in the earlier 860s. The mission was requested by the Rus' soon after a great fleet had sailed to Constantinople, looting the suburbs but apparently coming to grief in a storm on the way back. This Viking-style raid had at least the co-operation of the Rus' leadership and our main Byzantine source for the subsequent mission intimates that its purpose was to convert the ruler and notables responsible.[8] Many participants in the 860 expedition are likely to have been newcomers to the lands east of the Baltic and a fresh influx of fortune-seeking war-bands could well account for the disorder and political discontinuity evident for the final third of the century. Staraia Ladoga seems to have been razed to the ground between c.863 and c.871; around the same time there was a conflagration at Gorodishche and other settlements in the Volkhov basin suffered devastating fires in the second half of the ninth century.

One cannot be sure whether the archaeological evidence registers one wave of turbulence or recurrent bouts. But the damage done to two outstanding emporia cannot have been without political implications, and there was probably at least one change of princely regime. The Byzantine mission could well have been dislodged by such upheavals: there is no further trace of a prelate among the Rus' for a hundred years. The violence did not put paid to commercial vitality and may actually have been prompted by it, in that accumulation of silver and other treasure could be used to win followers and spectacularly raise one's status, while one of the main 'products' exchanged for dirhams was slaves, a trade involving at least the threat of duress. But incessant free-for-all violence was deleterious to so intricate a network, consisting of clusters of settlements around major emporia, towards which countless outlying 'feeders' contributed the most important product of all, furs. So it would not be surprising if a rather tighter political order emerged after a period of instability. One hint is the construction at Staraia Ladoga of what was apparently a citadel, surrounded by limestone slabs. Across the river from the expanding settlement, at Plakun, warriors armed in Scandinavian mode began to fill a separate burial ground. In the mid-890s a 'great hall' was built, partly from dismantled ship's timbers, and this could well have been where a prince or governor lived. The ensemble may register an attempt to guard the western approaches of Rus' against further marauders or conquerors from the Scandinavian world.

At the other end of the Volkhov, Gorodishche likewise recovered from physical destruction. By the end of the ninth century structures were being raised on boggier ground below the original hill-fortress. Workshops turned out Scandinavian-style brooches for women, weaponry and other metalwork for men. Silver, glass beads and other semi- de luxe items from eastern markets were dealt in, hoarded or worn as ornaments and, as at other centres of the trading nexus, pottery was beginning to be turned on the wheel rather than moulded by hand. Grandees, full-time warriors and wealthy wives were probably of Scandinavian stock, like the princely family presumed to have presided over them. But the majority of those choosing to work bone, wood and clay at Gorodishche were Slavs and Finns, some having travelled great distances to do so. Finds of their products attest this. The composition of the populations of other centres such as Pskov varied according to circumstances, but a constant is the presence of wealthy, armed, Scandinavians.

In the later ninth century a number of settlements, some quite sizeable and accommodating new arrivals from the Aland isles, appeared near the largely Finnish settlements flanking major lakes and rivers connected with the upper Volga. Their inhabitants, like many of the locals, engaged in the fur trade and it was probably prospects of self-enrichment as well as the fertile soils around Lake Nero and Lake Pleshcheevo that attracted them. The area offered good hunting and trapping, and connections between centres such as Sarskoe and fur-yielding regions much further north were long established. The newcomers' boatmanship provided means of reaching lucrative markets by water. Towards the end of the ninth century a new political structure formed on the middle Volga, under the auspices of the khagan of the Bulgars; the Bulgars themselves amassed huge quantities of furs from the north through barter and tribute collection. Two or three weeks' river journey to the Volga mouth brought one to the Khazar capital, Itil, while caravan routes led overland to the Samanid realm in Transoxiana. From the end of the ninth century the Samanids issued immense quantities ofdirhams to stimulate trade. The Bulgar khagan took from them his first silver coins' designs, and soon the Bulgar elite was Muslim, with mosques and schools. The Rus' newcomers to the upper Volga fully exploited their relative proximity to ample supplies of silver. Tenth- century Samanid dirhams form easily the largest group of Islamic coins found in what is now Russia and a high proportion of those found in the Baltic world. These exchanges did not, however, require a particularly high level of regular co-ordination or armed protection. So although the Volga Rus' and their collaborators made up a kind of polity, perhaps for a while distinct from that in the north-west, they did not create a tight politico-military structure. Silver in the north-east was too easily obtainable and shared out too widely; the routes to northernmost furs were too multifarious. In so far as order needed to be maintained along the middle and lower reaches of the Volga, the Bulgars and Khazars were already there in force.

The installation of northerners on the middle Dnieper towards the end of the ninth century may be viewed against this background. Their cultural characteristics - including language - were still preponderantly Scandinavian and they will have been deemed Rhos, much as the envoys to Byzantium in 838/9 had been. But in so far as status in the burgeoning 'urban' networks was attainable by wealth, advance was open to a wider range of individuals and outriders willing to adopt the elite's working practices. Besides, a likely by-product of the trade in nubile slave girls was children of mixed origins. The newcomers from the north used building techniques characteristic of settlements such as Staraia Ladoga rather than the middle Dnieper region. Log cabins were built on the damp soil beside the river at Kiev in the 890s, judging by dendrochronological analysis, and many structures served as workshops or warehouses. The riverside took on a new importance in the economy of what was still a small town. Kiev had been of significance as an emporium in antiquity, a convenient point for bartering forest produce for products of the steppes and southern civilisations. And it may well have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders shuttling between Western Europe, Itil and China. But only around the end of the ninth century did the Dnieper gain primary importance as a waterway. Kiev became the trading base of navigators capable of negotiating the fearsome Rapids downstream and then, from the Dnieper's mouth, raising masts and setting sail for markets across the sea. It was essentially for this purpose that northerners installed themselves in force at Kiev, Chernigov and nearby Shestovitsa.

Within a few years emissaries were negotiating with the Byzantine emperor and gaining the right for Rus' to trade toll-free in Constantinople itself, entering the city in groups of fifty 'through [only] one gate, without their weapons'. Provided that they brought merchandise, free board and lodgings were theirs for six months as well as 'food, anchors, ropes and sails and whatever is needed' for the return journey.12 An initial charter of privileges was soon followed by a bilateral treaty laying down procedures to settle likely disputes between individual Rus' and Byzantines, and also regulations for shipwrecks and due restitution of cargo. The emissaries' provenance is uncertain, but all five of those named as responsible for the first agreement recur among the fourteen listed for the September 911 treaty. Such continuity and regard for law and order implies a political structure, while the emissaries' names have a Nordic ring: Karl, Rulav, Stemid.

The northerners' move to Kiev might initially have been an attempt at secession from the other Rus' strongpoints, reminiscent of the tale of Askold and Dir. But these traders could scarcely have stood alone for very long, seeing that the finest furs originated far to the north. The 911 treaty, if not its precursor, most probably involved northern-based princes, as well as magnates newly installed on the middle Dnieper. By contrast with Kiev a centre such as Gorodishche was huge and populous, and the military potential of its ruling elite correspondingly formidable. In the early tenth century as earlier, this elite had a paramount leader. An Arab envoy to the Bulgars, who observed Rus' traders on the middle Volga in 922, evoked the court of the Rus' ruler. Residing on a huge throne together with forty slave girls, he mounts his horse without ever touching the ground; 400 'bravest companions' live in his 'palace', 'men who die with him and kill themselves for him'. A lieutenant commands troops and fights his battles.[9] The Rus' debt to Khazar political culture is clear from this and other evidence, including the style of dual rulership, the title ofkhagan and use of variants of his trident-like authority symbol. It may well be that their sacral ruler was ensconced in the north, at Gorodishche, as late as the 920s. The Rus' on the middle Dnieper, while affiliated to this polity, may also have paid tribute to the Khazars. In the mid-tenth century a Khazar ruler still regarded the Severians, Slavs near the middle Dnieper, as owing him tribute, while Kiev had an alternative, apparently Khazar, name, Sambatas.[10]

Princes of Kiev and the 'Byzantine connection': challenge and response

The earliest firm evidence of Rus' paramount rulership based in the region of Kievisforthe son ofRiurik, Igor', andheis only clearly attested there c.940.Itis

significant that the politico-military locus of Rus' shifted south little more than a generation after northerners first arrived in force on the middle Dnieper. This registers the rapid development and allure of the 'Byzantine connection', in terms oftrading and the wealth it could yield. But it also reflects a unique state of affairs. Demand in Byzantium was particularly strong for slaves and this was of practical convenience to the Rus' because, unlike inanimate goods, slaves could disembark and walk their way round the most hazardous of the Rapids. Other perils, including steppe nomads and shipwreck, tipped the Rus' self- interest in favour of an agreed command structure for voyages in convoy and regular dealings with the Byzantine authorities. So did the need to ensure a steady influx of slaves and confront the relatively well-organised and well- armed Slav groupings in the region of the middle Dnieper. Possessing towns and led by 'princes', they could resist tribute demands deemed excessive. Perhaps most important of all, the Rus' leadership needed to deal diplomatically or otherwise with the Khazar realm, whose resilience is easily overlooked. Events from c.940, the first in Rus' relatable with any degree of confidence, tend to bear this out.

Around that time a Rus' leader was impelled by the Byzantine government 'with great presents' to seize the Khazar fortress guarding the Straits of Kerch. Subsequently the Rus' were dislodged and their leader, named by our Khazar source as 'H-l-g-w', was overpowered and obliged to attack Byzantium. Reluctantly he complied and the Rus' expedition lasted four months, but the Byzantines were 'victorious by virtue of Fire'.[11] The latter details concur with our data for the well-attested Rus' attack on Constantinople of 941, the one serious mismatch being that its leader was Igor'. But the name H-l-g-w could well register the Nordic 'Helgi', and the earliest extant precursor of the Primary Chronicle actually names Igor' and Oleg (the Slavic form of Helgi) as jointly organising a raid against Byzantium.[12] The slight discrepancies in our sources could well reflect a joint arrangement, reminiscent of the dual ruler- ship mooted by Ibn Fadlan and the chronicle itself. The debacle recounted by our Khazar source also implies the precariousness of the Rus' hold on the middle Dnieper, while the importance of privileged access to Byzantine markets would be demonstrated a few years later. Igor' apparently lacked the wherewithal to satisfy his retainers and was put to death while trying to raise additional tribute from the Derevlians. Their prince sought the hand of Igor' 's widow, Ol'ga, albeit unsuccessfully. By this time, however, a new treaty had been negotiated with the Byzantines and commerce resumed. Princess Ol'ga, acting as regent, took measures to regularise the payment of tribute and set up hunting lodges where birds - probably of prey - could be caught for shipping to Byzantium together with furs, wax, honey and slaves. Ol'ga herself sailed to Constantinople, partly to confirm or improve the terms of the foresaid treaty. She was received at court 'with princesses who were her own relatives and her ladies-in-waiting' as well as 'emissaries of the princes of Rhosia and traders'.[13] During her stay Ol'ga was baptised and took the Christian name of the emperor's wife, Helena. However, no bishop accompanied Ol'ga-Helena back to Rus', and by autumn 959 she was asking Otto of Saxony for a full religious mission. Eventually a bishop, Adalbert, was sent but he soon returned together with his followers, describing the venture as futile.[14]

Evaluation of these events is difficult. Even the date of Ol'ga's visit to the emperor is controversial. The year 946 is one possibility but the main alternative, 957, has its merits, not least in more or less reconciling chronological pointers in the Rus' and Byzantine sources. What is certain is that Ol'ga made her journey against a background of economic boom and competent organisation. Constantine VII himself describes the marshalling of convoys at Kiev every spring. Slaves, together with the tribute collected over the winter by 'their princes (archontes) with all the Rhos', were loaded aboard for a voyage tailed by opportunistic nomads: if a boat was wrecked in the Black Sea, 'they all put in to land, in order to present a united front against the Pechenegs'.[15]The underlying stability of the princely regime is suggested by its survival through major setbacks and challenges in the 940s, although this owed something to Ol'ga's personality. A concentration of wealth and weaponry in the middle Dnieper region is also suggested by the finds of chamber graves at Kiev and Shestovitsa. Their occupants were equipped for the next world with arms and riding gear - sometimes horses or slave girls, too - while their dealings in trade are signalled by the weights and balances accompanying them (see Plate 1). Most were probably the retainers of the princes and other leading notables. The number of chamber graves on the middle Dnieper is not vast, but this tallies with Constantine VII's indication that Rus' military manpower was finite, further grounds for self-discipline.

The risks did not throttle trading along the waterway to Byzantium, and its range and vigour are registered at the site of modern Smolensk's precursor. Now called Gnezdovo, this was located near the outflow into the Dnieper of a river accessible via portages from many northern waterways, including the Western Dvina and Lovat. Its raison d'etre was as emporium and service station for boats hauled over lengthy portages and in need of repair or replacement. From the mid-tenth century the settled area expanded drastically to cover approximately 15 hectares by the century's end and it is from this period that the largest, most lavishly furnished, barrows date. Ten or so contain traces of boat-burnings and while finds of a few iron rivets need not denote the burning of entire boats, their symbolic value is none the less eloquent - of Scandinavian-style funerary rites and the status attaching to trade and boats. Pairs of tortoiseshell brooches attest the burial of well-to-do Scandinavian women and some chamber graves contain Byzantine silks, the single most valuable luxury obtained from 'the Greeks'. Many persons were drawn to Gnezdovo, whether to drag boats or make a living in smithies and other workshops. A pot with a Slavic graffito from the first half of the tenth century denotes, probably, a literate Slav resident. Comparable expansion was under way at Gorodishche, whose overspill began to take up the nearby site of Novgorod. The influx of Muslim dirhams, which had so long driven its economic growth, continued but Western markets were also involved in the networks of exchange. Silks of probable Byzantine manufacture played some part, as witness finds in the burial ground at Birka and, occasionally, still further west, in Scandinavian-dominated parts of the British Isles where dirhams of the later ninth and earlier tenth centuries have also come to light.

The pattern of finds of luxury goods is loosely congruent with that of chamber graves. Chamber graves have been excavated at Birka, Hedeby and elsewhere in Denmark, a kind of 'social register' of the well-to-do. Their occupants had not necessarily belonged to ruling elites, and war-bands could cause serious disorder, especially when legitimate authority was in dispute. However, the direct involvement of many retainers in trading gave them an underlying interest in stability. The distribution pattern of the chamber graves in Rus' charts princely strongpoints and the most regulated trading nodes from the end of the ninth century onwards: from Staraia Ladoga, Gorodishche and Pskov down to Gnezdovo and the middle Dnieper, with a cluster at Timerevo on the upper Volga. Membership of war-bands and trading companies was not closed to talent, and costumes, riding gear and ornament designs were adopted from both host populations and more exotic cultures. But their breeding- and, frequently, homing-ground was the Scandinavian world, long-range travel being a mark of membership.

Christianising impulses reached the Rus' in several ways - from individual warriors and traders frequenting Swedish and Danish kingly courts and emporia; from those who journeyed to Byzantium and back; and through missionary efforts by Byzantine emperors and churchmen. These impulses can hardly have failed to affect the sacral aspects of rulership, whatever its precise complexion at that time, and by 946 baptised Rus' were being paraded at receptions in the Great Palace. Whether to impress her Christian notables or out of personal belief, Ol'ga proceeded to associate herself sacramentally with the ruling family in Byzantium. The Byzantines' apparent reluctance to send a mission is understandable in light of Bishop Adalbert's experiences. After his mission was abandoned, several members were killed and Adalbert claimed that he had only narrowly escaped himself. Ol'ga maintained a priest in her entourage until she died in 969 and the presence of other priests and a church in Kiev would not be surprising, given that a number of leading Rus' were Christian. Yet powerful Rus' were opposed to Christianisation. Their stance is epitomised by the Primary Chronicle's tale of Ol'ga's attempts to convert her son, Sviatoslav. He responded: 'My retainers will laugh at this.'20 This image of Sviatoslav as swashbuckler, consciously reacting against his mother's new-found eirenic disposition, accords with an eyewitness description. Sviatoslav's head was shorn save for one long strand of hair, a mark of nobility among Turkic peoples. Members of the Rus' elite were no strangers to artefacts evoking myths and customs of steppe dwellers. The mounting on a drinking-horn depicts a scene of men and predators in combat which may evoke Khazar concepts of sacral kingship. The horn, one of a pair, was buried in the barrow of a Chernigov magnate in the 960s, as was a statuette of Thor.

Sviatoslav: the last migration

Sometime in the mid-960s Sviatoslav forged an alliance with a group of nomads, the Oghuz, and launched a joint attack on the Khazars. Sviatoslav's aggression was reportedly triggered by his discovery that the Viatichi were paying tribute in 'shillings' to the Khazars.21 This vignette illustrates the lucrative involvement of the Slavs with the trading nexus; the long reach of the Khazars;

and, more generally, the many compass-bearings of the Rus'. In laying waste to the Khazar capital of Itil, Sviatoslav destroyed a rival power intruding into his own sphere, and in attacking the Volga Bulgars and the Burtas he was perhaps seeking unhindered access to the Samanid realm, the main source of Rus' silver. Sviatoslav did not, however, try and base himself on the lower Volga or at the Straits of Kerch, where his forces sacked the Khazar fortress of S-m-k-r-ts. In fact the influx of silver from Samanid mints began to falter from around this time. Instead he opted for Pereiaslavets on the lower Danube. This, he determined, would be 'the centre of my land, for there all good things flow: gold from the Greeks, precious cloths, wines and fruit of many kinds; silver and horses from the Czechs and Hungarians; and from the Rus' furs, wax, honey and slaves'.[16] The immediate reason for Sviatoslav's intervention in the Balkans in 968 was fortuitous. The Byzantine emperor, Nicephorus II, incited him to raid Bulgaria, offering gold as an inducement. Byzantine sources portray the Rus' as marvelling at the fertility of the region, and the emissary delivering the gold is said to have urged Sviatoslav to stay there, furthering his own ambitions for the imperial throne. But Sviatoslav probably needed little prompting to stay on in the south. He had already shown impatience with the status quo in shattering the Khazar hegemony and, as stressed above, the Rus' on the middle Dnieper were hemmed in by many constraints. The Pechenegs were incited by the emperor to attack Kiev, once Sviatoslav showed signs of overstepping his brief, and the town came close to surrendering. But Sviatoslav proved able to come to terms with the nomads and many Pech- enegs accompanied him back to the Balkans in, probably, the autumn of 969. Hungarians, too, joined in and with their help Sviatoslav ranged as far south as Arcadiopolis, impaling prisoners en masse. The atrocities were not entirely random. Sviatoslav seems to have envisaged a commonwealth spanning several cultures and climate zones: his young sons Iaropolk, Oleg and Vladimir were respectively assigned to Kiev, the Derevlian land and Novgorod, while Sviatoslav ensconced himself near the Danube's mouth. The Bulgarian Tsar Boris was left in his capital, Preslav. Rus' garrisons were installed there and in Danubian towns. Sviatoslav's underlying aim was probably to foster trade along and between major riverways, employing nomads to police the steppes and keep the peace. His base had the advantage of proximity to the markets of both 'the Greeks' and Central Europe, where Saxon silver was beginning to be mined. Sviatoslav was not the first Rus' leader to have a keen eye for commercial openings.

Sviatoslav overestimated the Byzantines' willingness to accept him as a new neighbour. In April 971 Nicephorus' successor, John I Tzimisces, led a surprise offensive through the Haemus mountain passes and soon Sviatoslav was holed up at Dorostolon. Retreat down the Danube was barred by the imperial fleet, while most of the nomads were won over by imperial bribery. In late July, after ferocious fighting, a deal was struck. The Rus' received grain, safe-conduct and confirmation of the right to trade at Constantinople in return for Sviatoslav's written oath never again to attack imperial territory or Bulgaria. His ambitions had canniness. While reputedly adopting the nomads' lifestyle, with a saddle for pillow,[17] Sviatoslav seems to have determined that the best prospects for commercial growth lay with Byzantine and Western European markets rather than - as traditionally - the East. Had Byzantine forces not then been in peak condition, a Danubian Rus' might have formed. As it was, the outcome of the campaigning was uncertain only days before Sviatoslav proposed terms: he did not actually surrender nor does he seem to have given up his captives or his loot. These spoils and putative slaves were his undoing. Concern for shipping them back to Rus' slowed down withdrawal, and Sviatoslav and his men were ambushed by Pechenegs at the Dnieper Rapids early in 972. Few escaped and Sviatoslav's own skull became a plated drinking cup, a use to which steppe peoples put the heads of enemies.

972-C.978 Fragmentation

Sviatoslav's demise brought instability to the princely dynasty and allowed outsiders to set themselves up near the 'way from the Varangians to the Greeks'. His two eldest sons, Iaropolk and Oleg, fell out after a clash between hunting parties which cost Liut, the son of Iaropolk's military commander, his life. Iaropolkthen attacked and defeated his brother, and Oleg perished in the crush of fugitives. Vladimir fled 'beyond the sea'. The Primary Chronicle's account is laconic, a tale of the commander's vengeance for Liut. Nonetheless its intimations of quarrels over resources involving princely retainers may not be sheer fiction. There had been problems with satisfying retainers after Igor' 's disastrous expedition to Byzantium; on that occasion the Derevlians themselves had been involved. Both episodes imply reduced princely circumstances after defeat by the Byzantines and probable dislocation of trade. There are hints that Iaropolk attempted a rapprochement with Emperor Otto I, in that Rus' envoys were among those at Otto's court in March 973. An attempt to step up exports of furs and slaves to silver-rich Central European markets through amity with their chief protector would be quite understandable, a substitute for Byzantine and oriental outlets. Taking advantage of the political disarray, figures with Scandinavian names such as Rogvolod (*Ragnvaldr in Old Norse) and Tury reportedly set themselves up at, respectively, Polotsk and Turov. These strongholds could give access to the West but lay near 'the way from the Varangians to the Greeks'. This route had not lost its magnetism and drew Vladimir Sviatoslavich back. Having lodged at some Scandinavian court or courts, he mustered a company of retainers and led them to Rus'. He enjoyed advantages over other power holders or seekers, being a son of Sviatoslav and acquainted with leading figures of Gorodishche-Novgorod. Dobrynia, his mother's brother, had in effect been his guardian there and was probably still with him. Vladimir was thus better able to enlist many citizens, Finns as well as 'Slovenes', and although they may have been inexpert fighters, their numbers together with the 'Varangians' proved more than a match for Rogvolod. Vladimir's personal qualities also gave him a head start. Ruthless and shrewd, he put to death Rogvolod, reportedly a 'prince',24 and also Rogvolod's sons. But he took Rogvolod's daughter to wife and led his Novgorodians and retainers to Kiev. There he suborned the commander of Iaropolk's defence force and invited his half-brother to parley in their father's old stone hall. As Iaropolk entered, 'two Varangians stabbed him in the chest with their swords'.25 Thus Vladimir gained the throne city of Kiev around 978.

Vladimir's force, his legitimacy deficit and turning to the gods

Vladimir suffered the handicap of lacking reputable ties with local elites or populations on the middle Dnieper. He was of princely stock, but his mother had been Sviatoslav's key-holder and of unfree status. Vladimir had spent his youth far away and lacked a longstanding retinue, once he had dispatched his 'Varangian' retainers to Byzantium. He sent them off after declining to pay them in precious metal and then reneging on a promised payment in marten- skins. This episode demonstrates the high running costs of war-bands and also Vladimir's political nous. He was anxious not to antagonise the better-off inhabitants of Kiev through over-taxation. As at Novgorod, the active cooperation of the citizenry was needed to underpin his regime: at least one prominent supporter of his murdered half-brother had fled to the Pechenegs and 'often' took part in their raids.26

Lack of material resources partly explains the tempo of Vladimir's early years in power. He needed to reimpose and extend tribute collection so as to feed the markets of Kiev and secure means for rewarding his followers. He led campaigns to the west and campaigned repeatedly against the redoubtable Viatichi, so as to reimpose tribute on them. Besides restoring the exchange nexuses, war-leadership could bond Vladimir with contingents of warriors of his choosing and strengthen his power base. This, however, presupposed victories and the public cult he instituted was designed to induce them, besides appealing to the heterogeneous population of the middle Dnieper region. The 'pantheon' of wooden idols set up outside his hall in Kiev was headed by Perun, the Slavic god of lightning and power. This is our first evidence of a prince's attempt to organise public worship and to associate his rule with a medley of gods, some quite local, others (like Perun) with a widespread following. Vladimir presumably hoped to bolster his legitimacy through such measures, and to win further victories. After subjugating the Iatviagians in the west, he ordered sacrifices in thanksgiving to the idols outside his hall. We know of this only because the father of a boy chosen by lot for sacrifice happened to be Christian, a Varangian who had come from 'the Greeks' to reside in Kiev and who refused to give up his son, at the cost of his own life. Vladimir's command- cult thus gave rise to 'martyrs'. But judging by the coffins and contents of several graves in Kiev's main burial ground, Christians and part-Christians lived peaceably with pagans, and were buried near them. The incessant circulation of travellers between the Baltic and Byzantium prompted individual Rus' to be baptised and Christianity was quite well known to inhabitants of the urban network, but this did not oblige their prince to follow suit.

Vladimir's campaigns brought mastery of the towns between the San and the Western Bug. Among these were Cherven and Peremyshl' (modern Przemysl in Poland), population centres astride routes to Western markets. The run of victories abated when Vladimir suffered a setback at the hands of the most sophisticated power adjoining Rus', the Volga Bulgars. He had presumably hoped to subjugate their markets, too, but on his uncle's advice came to terms. Dobrynia is supposed to have pointed out that these enemies wore boots: 'Let us go and look for wearers of bast-shoes!'27 His implication that Vladimir should seek tribute from simpler folk was demeaning, setting limits to the resources he could bring under his sway. To that extent, Perun and his fellow gods had failed to 'deliver', and a quest for a better guarantor of victory would be understandable. It may be no accident that the Primary Chronicle's next entry after Vladimir's reverse on the Volga is the arrival of a Bulgar mission to convert him to Islam, in the mid-980s. This serves as the preliminary to a lengthy account sometimes termed Vladimir's 'Investigation of the Faiths'. Most - though not all - of the material in the 'Investigation' is stylised doctrinal exegesis. But its image of Vladimir investigating four brands of monotheism - Eastern and Western Christianity besides Islam and Judaism - encapsulates what the immediately preceding chronicle entries and the general historical context lead one to expect. Rus' rulers since Ol'ga had been considering alternative sacral sources of authority. The cult of an all-powerful God had its attractions for a prince pre-eminent, yet light on legitimatisation, as Vladimir was. One might consider Vladimir's eventual choice of Byzantine Christianity inevitable, given the exposure of so many of his notables to its wealth and majesty. But Vladimir could have obtained a mission from the Germans, following his grandmother's precedent, had the government during Otto III's minority been better placed to further mission work. And there is evidence that Vladimir sent emissaries to Khorezm and obtained an instructor to teach 'the religious laws of Islam'. This demarche by a Rus' 'king' is recounted by a late eleventh-century Persian writer and it is compatible with the Primary Chronicle's tale of the dispatch of enquirers to the Muslims, Germans and Byzantines.[18] Seeking a mission from the Orient was nothing untoward, even if commercial ties with Central Asia were set to slacken.

An unusual conjuncture of events caused Vladimir to settle for a religious mission, marriage alliance and treaty with the senior Byzantine emperor, Basil II. The outlines are clear: by early 988 Basil was beleaguered in his capital by rebel armies encamped across the Bosporus, while a Bulgarian uprising against Byzantine rule in the Balkans was in full flame. Basil came to terms with Vladimir, sending his sister as bride in exchange for military aid; Vladimir's baptism was the inevitable corollary of this. Vladimir sent an army - 6,000- strong by one account - and they caught the rebels off-guard at Chrysopolis in the opening months of 989, at latest. This turned the tide. Within a couple of years the military rebellion ended and Anna Porphyrogenita settled in Kiev with her spouse, who took the Christian name 'Basil', in honour of his brother-in-law. These outlines convey the essence, that Basil II's domestic interests momentarily converged with those ofVladimir. The Rus' ruler could supply desperately needed troops and in return received generous concessions, such as had not been vouchsafed to Ol'ga.

The exact course and significance of events is harder to reconstruct, especially the expedition of Vladimir to Cherson. The Primary Chronicle's account draws on disparate sources, and our near-contemporaneous foreign sources are sketchy. Various explanations for Vladimir's expedition are feasible. This could have been a 'first strike', akin to his seizure of Cherven and other towns to the west. Cherson had prospered greatly in the tenth century and the town's built-up area expanded. Vladimir may have exploited Basil II's preoccupation with rebellions to grab the Crimea's richest town, reckoning that he could either mulct its revenues or use it as a bargaining counter. As part of an ensuing treaty, he may have sent Basil military aid. Alternatively, Vladimir may have seized Cherson in retaliation for Basil's slowness to honour an initial agreement on similar lines, forcing him to abide by it. Or the capture of Cherson could even have been carried out as a form of assistance to Basil if, as has been suggested, the townsfolk had sided with the rebellious generals.[19] What is not in doubt is that Vladimir exploited Byzantine disarray in order to secure his own authority, underwritten by Almighty God.

Vladimir-Basil, 'new Constantine' and patriarch

Vladimir was acclaimed by later churchmen as an 'apostle among rulers' who had saved them from the devil's wiles.[20] The devil bemoaned expulsion from where he had thought to make his home. Such imagery was fostered by the spectaculars staged in the wake of Vladimir's own baptism, and in the second half of the eleventh century a Kievan monk could still recall 'the baptism of the land of Rus".[21] Kiev's citizens were ordered into the Dnieper for mass baptism. The idol of Perun was dragged by a horse's tail and thrashed with rods, then tossed in the river and kept moving as far as the Rapids, clear of Rus'. Vladimir ordered 'wood to be cut and churches put up on the sites where idols had stood'; 'the idols were smashed and icons of saints were installed.'[22]

This scenario of purification and transformation must be qualified. A fair proportion of the Rus' elite were probably more or less Christian just before the conversion: there had been baptised Rus' in the 940s. Conversely, the extent and nature of the 'Christianisation' of ordinary folk, especially those living outside towns and the immediate sway of princely agents, is very uncertain. Even the chronicle merely has Vladimir getting people baptised 'in all the towns and villages'. Priests were assigned to towns, rather than villages. It was pagan idols, sanctuaries and communal rituals - alternative focuses of loyalties and expectation - that were swept away.

The churchmen's portrayal of Vladimir's achievement is not, however, sheer make-believe. The initiatives taken by Vladimir were intended to associate his regime indissolubly with the Christian God and His saints, making promotion of the Church a function of princely rule. And he succeeded in embedding a version of Christianity in the political culture of Rus'. No aspiring prince in Rus' mounted a pagan revival, unlike some usurpers in Scandinavia. Vladimir's Christian leadership predicated victories and the vein of triumphalism in the Primary Chronicle's depiction of Vladimir's activities at Cherson probably relays his own propaganda. But he also exploited his new-found ties with a court renowned among the Rus' for God-given wealth. Anna Porphyrogenita would eventually be laid to rest in a marble sarcophagus beside Vladimir's own, a symbol of parity of status as well as conjugal bonds. Anna probably lived in the halls built on the Starokievskaia Hill and graced the feasts held there every Sunday, presumably after religious services in the church of the Mother of God which the halls flanked. These stone and brick buildings were the work of 'masters' from Byzantium and were embellished with wall-paintings and marble furnishings. The church's design seems to have followed that of the main church in the emperor's palace complex, the church of the Pharos, and they shared a dedicatee, the Mother of God. Vladimir was inviting comparisons between his own residence and that of the emperor. The message that he could match the Greeks was underlined when he placed a certain Anastasius in charge of his palace church. Reputedly, Anastasius had betrayed Cherson to Vladimir by revealing where the pipes supplying its water ran; once these were cut, the thirst-stricken Chersonites surrendered.[23] A number of other priests from Cherson were assigned to the church, which became known as the 'Tithe church' (Desiotinnoio) because of the tenth of revenues allocated to it. The relics of St Clement brought back from Cherson had a prominent position, while looted antique statuary was displayed outside. Thus the show church served as a kind of victory monument to Vladimir's role in the conversion of his people.

The middle Dnieper is the region where Rus' churchmen's rhetoric concerning 'new Christian people, the elect of God' rings most true. In order to protect his cult centre, Vladimir established new settlements far into the steppe, taking advantage of the black earth's fertility. Kiev itself was enlarged to enclose some 10 hectares within a formidable earthen rampart and ramparts of similar technique were raised to the south of the town. The construction of barriers and strongholds along the main tributaries of the Dnieper brought a new edge to Rus' relations with the nomads. Although never unproblematic, these had hitherto involved constant trading and had more often than not been peaceable. There was now, according to the Primary Chronicle, 'great and unremitting strife'34 and although Kiev was secure, even the largest of the fortified towns shielding it came under pressure from the Pechenegs. Belgorod, south-west of Kiev, underwent a prolonged siege. It did not, however, fall and this owed something to the layers of unfired bricks forming the core of the ramparts, which still stand between five and six metres high. They enclosed some 105 hectares, and a very high level of organisation was needed to supply the inhabitants. The princely authorities adapted techniques from the Byzantine world, not only brick- and glass-making but also plans for large cisterns and a beacon system perhaps fuelled by naphtha. Few new towns matched Belgorod or Pereiaslavl' in size and many settlements lacked ramparts, the nearby forts serving as places of refuge. But the grain and other produce grown by the farmers fed the cavalrymen and horses stationed in the forts, sickles and ploughshares were manufactured in the smithies, and nexuses of trade burgeoned. Finds of glazed tableware and, in substantial quantities, amphorae and glass bracelets attest the prosperity of the settlements' defenders. The risks of voyages to Byzantium were mitigated - though never dispelled - by ramparts beside the Dnieper and a large fortified harbour near the River Sula's confluence with the Dnieper, at Voin. Cavalry could escort boats to the Rapids, and from the late tenth century the Byzantine government let the Rus' establish a trading settlement in the Dnieper estuary.

The middle Dnieper region had not been densely populated before Vladimir's reign. He is represented by the Primary Chronicle as rounding up 'the best men' from among the Slav and Finnish inhabitants of the forest zone and installing them in his settlements.35 The newcomers to the hundred or more forts and settlements in the great arc protecting Kiev were prime targets for evangelisers, as well as raiders. Divine intervention supporting princely leadership was in constant demand, and one of the few bishoprics quite firmly attributable to Vladimir's reign is that of Belgorod. At Vasil'ev Vladimir founded a church and held a great feast in thanksgiving, after hiding under its bridge from pursuing Pechenegs. The apparent intensity of pastoral care and the deracination of most of the population from northern habitats made inculcation of Christian observances the more effective. Judging by the funerary rituals in the burial grounds of these settlements, few flagrantly pagan practices persisted. Barrows were not heaped over graves in cemeteries within a 250-kilometre radius of Kiev, or in regions such as the Cherven towns where Christianity was already well established. Elsewhere barrows were much more common, although heaped over plain Christian burials. The small circular barrows often contained pottery, ashes and food symbolising - if not left over from - funeral feasts, occasions of which the Church disapproved.

The regions and key points where Vladimir's conversion transformed the landscape, physically as well as figuratively, were finite but the number of persons affected was considerable. New Christian communities were instituted in the middle Dnieper region and existing ones in the trading network massively reinforced, especially in the northern towns frequented by Christians from the Scandinavian world. Novgorod was made an episcopal see. Churches were most probably built and priests appointed in Smolensk and Polotsk, albeit without resident bishops. Even in north-eastern outposts, Christianity became the cult of retainers and other princely agents, and it appealed to locals trafficking with them and aspiring to raise their own status. At Uglich on the upper Volga (as at Smolensk, Pskov and Kiev itself) the pagan burial grounds were destroyed in the wake of Vladimir's conversion and in the first quarter of the eleventh century a church dedicated to Christ the Saviour was built. Soon members of the elite began to fill St Saviour's graveyard in strict accordance with Church canons. Vladimir's tribute collectors and other itinerant agents did not just owe allegiance in return for treasure such as his new-fangled silver coins, share-outs of tribute and sumptuous feasts featuring silver spoons, important as these were (for examples of Vladimir's silver coins, see Plate 2). They had religious affiliations with him: greed, ambition and concern for individual survival in life and after death fused with loyalty to the prince. Vladimir probably saw the advantages of instilling the faith into the next generation. There is no particular reason to doubt that the children of 'notable families' were taken off to be instructed in 'book learning' while their mothers, 'still not strong in the faith . . . wept for them as if they were dead'.[24]

The wording of the Primary Chronicle seems to treat book learning as more or less synonymous with studying the Scriptures and the new religion, and Vladimir stood to gain moral stature from enlightening his notables' children. One should not, however, suppose that the literacy which boys - maybe also girls - of his elite obtained was of much application to everyday governance. The administrative and ideological underpinnings of princely rule were still quite rudimentary, even if Vladimir loved his 'retainers and consulted them about the ordering of the land, about wars and about the law of the land'.[25]The 'land of Rus" was an archipelago of largely self-regulating communities. Extensive groupings in the north were still considered tribes, most notoriously the Viatichi. It was mainly in Vladimir's new fortresses and settlements in the middle Dnieper region that princely commanders, town governors and agents were numerous enough to intervene in the affairs of ordinary people; the standing alert against the nomads required as much. But even there the officials seem to have had little occasion to issue deeds or written judgements. Nor do they seem to have played a commanding role in adjudicating disputes or enforcing laws. There had longbeen some sense of due legal process among the Rus'. Procedures for making amends for insults, injuries, thefts and killings inform the tenth-century treaties with the Byzantines. However, practical measures for conflict resolution of mutually inimical parties fell far short of upholding an inherently ethical code, of punishing upon Christian principle actions deemed sinful. A hint of attitudes towards justice as a non-negotiable quality is offered by a passage in the Primary Chronicle, perhaps first set down before Vladimir's reign passed from living memory. Vladimir's bishops urged punitive action against robbers, for 'you have been appointedby God to punish evil-doers'. Vladimir gave up exacting fines in compensation for offences (viry) but later he reverted to 'the ways of his father and grandfather'.[26] The story shows awareness in Church circles that Rus"s 'new Constantine'[27] had only limited conceptions concerning his authority.

Vladimir's regime rested less on elaborate institutional frameworks or justifications in law than on well-oiled patronage mechanisms and the aura with which his paternal ancestry invested him. The blood of a murdered half-brother on one's hands could be offset by imposing a well-ordered public cult. In every other way, family blood and concomitant bonds were assets that Vladimir exploited to the full. His maternal uncle, Dobrynia, seems to have been a mainstay and there is no sign of the multiplicity of 'princes' or magnates attested for the middle Dnieper in the mid-tenth century. The losses incurred during Sviatoslav's campaigns and his sons' internecine strife may have cleared what was always a hazardous deck. In any case, Vladimir quite soon came to rely on his own sons in what was probably a new variant of collective, family, leadership. He was not the first Rus' prince to assign sons to distant seats of authority, but he seems to have carried this out on a wider scale than his predecessors. Twelve sons are named and associated with seats by the Primary Chronicle, a likely evocation of the twelve Apostles. The actual number of sons assigned to towns may well have been greater, since the distinction between those born in wedlock rather than to a concubine was not sharply drawn. That Vladimir was the father was what mattered: they could deputise for him in a variety of places. If it is unsurprising that a son was installed in Novgorod, the failure to grace Pskov - the town of Vladimir's grandmother and probably a longstanding seat of authority - with a prince of its own is noteworthy. So is the assignment of sons to towns which, though of fairly recent origin, had proved to be potential power bases, Polotsk and Turov. When Iziaslav, Vladimir's first assignee to Polotsk, died in 1001, his son was permitted to take his place and, in effect, put down the roots of a hereditary branch of princes there; Iziaslav's mother hadbeen Rogneda, daughter of Rogvolod. Presumably Vladimir calculated that so strongly rooted a regime would block any future bids for Polotsk by outsiders. Princes were also sent to locales whose ties with the urban network had not been specifically 'political'. For example, Rostov was only developed into a large town in the 980sor 990s, when the local inhabitants were mainly the Finnic Mer. The newly fortified town was dignified with a resident prince, Iaroslav, and an oaken church was subsequently built. Some places of strategic importance but lacking recent princely associations were not assigned a prince. It was a governor who had to cope with Viking-type raids on Staraia Ladoga and the town suffered conflagrations, at the hands of Erik Haakonson in 997 and of Sveinn Haakonson early in 1015.

Sveinn raided down 'the East Way' at a time when the shortcomings of Vladimir's regime were becoming plain. Ties between father and sons could hold together for a generation of peace, but they were not immune from jockeying for prominence and ultimate succession. By around 1013 Vladimir's relations with one leading son, Sviatopolk, were so fraught that he was removed from his seat in Turov and imprisoned. And, ominously, Vladimir's relations with the occupant of the most important seat after Kiev itself deteriorated drastically. In 1014 Iaroslav, now prince of Novgorod, held back the annual payment due from that city to Kiev and Vladimir began detailed preparations for the march north. The fact that Vladimir was on such bad terms with two of his foremost sons suggests that thoughts about the succession were in the air. Iaroslav 'sent overseas and brought over Varangians' for what promised to be outright war.[28] However, Vladimir fell ill, putting off the expedition, and on 15 July 1015 he died.

Essentially, the vast 'land of Rus" was a family unit, with all the affinities and tensions germane to that term, and there were no effective ritual or legal mechanisms making for a generally accepted succession. Once the family 'patriarch' died, these uncertainties could only be resolved by a virtual free- for-all between the more or less eligible sons of Vladimir. The coming of Christianity fostered economic well-being, fuller settlement of the Black Earth region and cultural advance, while a kind of 'cult of personality' now invested Vladimir, accentuating the aura of princely blood. Over the centuries there would scarcely ever be a question of persons who were not his descendants seizing thrones for themselves in Rus'. This was partly due to force of custom and princely retinues' force majeure. But there was also symbiosis amounting to consensus across diverse populations and urban centres with a positive interest in the status quo - and in the profits to be had from long-distance trading. For these members of Rus', the tale of the summoning of Riurik from overseas had resonance. The regime fashioned by Vladimir could maintain order of a sort. There was no other overriding authority, no well-connected senior churchmen to knock princely heads together. But given the remarkable make-up of Christian Rus', how could it have been otherwise?

Kievan Rus' (1015-1125)

SIMON FRANKLIN

The period from 1015 to 1125, from the death of Vladimir Sviatoslavich to the death of his great-grandson Vladimir Vsevolodovich (known as Vladimir Monomakh), has long been regarded as the Golden Age of early Rus': as an age of relatively coherent political authority exercised by the prince of Kiev over a relatively coherent and unified land enjoying relatively unbroken economic prosperity and military security along with the first and best flowerings of a new native Christian culture.[29]

One reason for the power of the impression lies in the nature of the native sources. This is the age in which early Rus', so to speak, comes out from under ground, when archaeological sources are supplemented by native writings and buildings and pictures which survive to the present. From the mid-eleventh century onwards, in particular, the droplets of sources begin to turn into a steady trickle and then into a flow. Before c.1045 we possess no clearly native narrative, exegetic or administrative documents. By 1125 we have the first sermons, saints' lives, law codes, epistles and pilgrim accounts, as well as a rapidly increasing quantity of brief letters on birch bark and of scratched graffiti on church walls and miscellaneous objects.[30] Before the death of Vladimir Sviatoslavich no component of our main narrative source, the Primary Chronicle (Povest' vre- mennykh let) is clearly derived from contemporary Rus' witness; by the early twelfth century, when the chronicle was compiled, its authors could incorporate several decades of contemporary native narratives and interpretations. No building from the age of Vladimir Sviatoslavich or earlier survived above ground into the modern age. Monumental buildings from the mid-eleventh to early twelfth centuries can still be seen today - in varying states of completeness - the length of Rus', from Novgorod in the north to Kiev and Chernigov in the south. Still more survived until the mid-twentieth century, when they were destroyed either by German invaders or by Stalinist zealots.[31] These early writings and buildings came to acquire - and in some cases were clearly intended to convey - an aura of authority, a kind of definitive status as cultural and political and ideological models, as the foundations of a tradition.

Between 1015 and 1125, then, for subsequent observers Rus' emerged into the light, and immediately contemplated and celebrated its own enlightenment. Such perceptions are real and significant facts of cultural history. However, their documentary accuracy is debatable and our own retelling of the period is necessarily somewhat grubbier than the image.

Dynastic politics

Political legitimacy in Rus' resided in the dynasty. The ruling family managed to create an ideological framework for its own pre-eminence which was maintained without serious challenge for over half a millennium. To this extent the political structure was simple: the lands of the Rus' were, more or less by definition, the lands claimed or controlled by the descendants of Vladimir Sviatoslavich (or, in more distant genealogical legend, by the descendants of the ninth-century Varangian Riurik). But the simplicity of such a formulation hides its potential complexity in practice. It is one thing to say that legitimacy resided in the dynasty, quite another to determine how power should be defined and allocated within it. Legitimacy was vested in the family as a whole, not in any individual member of it. Power was distributed and redistributed, claimed and counter-claimed, among members of a continually expanding kinship group, not passed intact and by automatic right from father to son. The political history of the period thus reflects, above all, the interplay of two factors, the dynastic and the regional: on the one hand the issue ofprecedence or seniority within the ruling family; on the other hand - as a consequence of the distribution of power - the increasingly entrenched and often conflicting regional interests of its local branches.

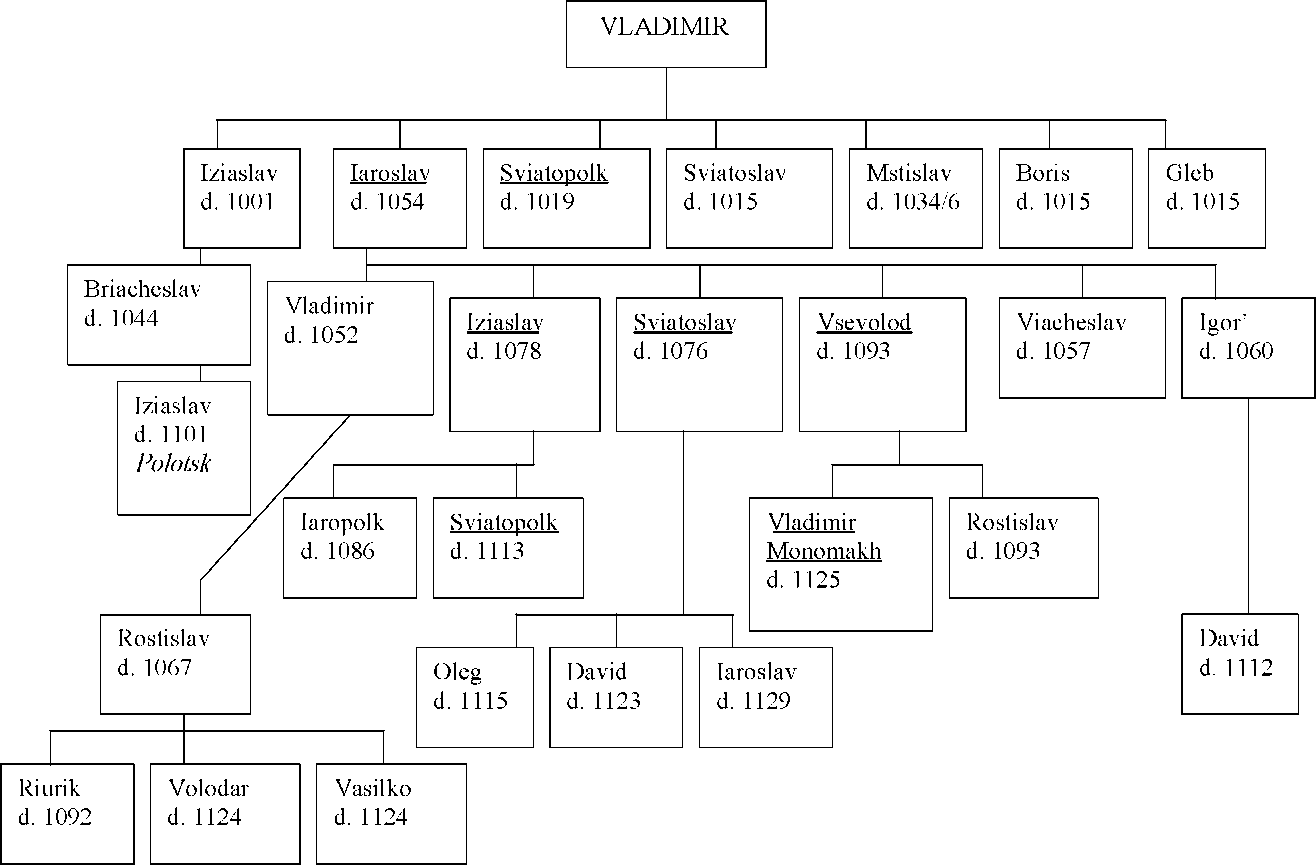

The changing patterns of internal politics are most graphically shown at moments of strain resulting from disputes over succession. Succession took place both 'vertically' from an older generation to a younger, and 'laterally' between members ofthe same generation, from brother to brother or cousin to cousin. Three times between 1015 and 1125 the dynasty had to adjust to 'vertical' succession: in 1015 on the death of Vladimir himself; in 1054 on the death of his son Iaroslav, and in 1093 on the death of his grandson Vsevolod (see Table 4.1). On each occasion the adjustment to 'vertical' succession introduced a fresh set of 'lateral' problems among potential successors in the next generation, and on each occasion the solutions were slightly different. Through looking at the sequence of adjustments to changes ofpower we can followthe development of a set of conventions and principles which, though never neat or fully consistent in their application, are the closest we get to a political 'system'.[32]

In 1015 Vladimir's sons were scattered around the extremities ofthe lands, for it had been his policy to consolidate family control over the tribute-gathering areas by allocating each of his sons to a regional base. One was given Turov, to the west, on the route to Poland; another had the land of the Derevlians, the immediate north-western neighbours of the Kievan Polianians; one was installed at Novgorod in the north, another at the remote southern outpost of Tmutorokan', beyond the steppes, overlooking the Straits of Kerch between the Black Sea and the Azov Sea. There were a couple of postings in the northeast, at Rostov and Murom, and one in Polotsk in the north-west. This was Vladimir's framework for ensuring that each of his sons had autonomous means of support and that the family as a whole could establish and maintain the territorial extent of its dominance.

On Vladimir's death this structure collapsed. Despite their remoteness from each other, the regional allocations were clearly not regarded as substitutes for central power (if we regard the middle Dnieper region as the 'centre'). The only exception was Polotsk, where Vladimir's son Iziaslav had already died and had been succeeded by his own son Briacheslav: there is no indication that Briacheslav competed with his uncles, and this is the first recorded example of a regional allocation coming to be treated as the distinct patrimony of a particular branch of the family. Relations between Vladimir's surviving sons, however, were more turbulent. Three were murdered (two of them, Boris and Gleb, went on to become venerated as saints),[33] and three more - Sviatopolk of Turov,

Table 4.1. From Vladimir Sviatoslavich to Vladimir Monomakh (princes of Kiev underlined)

Iaroslav of Novgorod, and Mstislav of Tmutorokan' - emerged as the principal combatants. From their widely dispersed power bases each used his own regional resources and contacts to reinforce the campaign for a secure place at the centre. Sviatopolk formed an alliance with the king of Poland, whose multinational force occupied Kiev for a while; Iaroslav augmented his local Nov- gorodian forces with Scandinavian mercenaries who helped him eventually to defeat and expel Sviatopolk; Mstislav gathered conscripts from his tributaries in the northern Caucasus, with whose aid he was able (in 1024) to negotiate an agreement with Iaroslav: he (Mstislav) would occupy Chernigov and would control the 'left-bank' lands (east of the Dnieper), while Iaroslav would control the 'right bank' lands including Kiev and Novgorod. Only on Mstislav's death (in 1034 or 1036) did Iaroslav revert to his father's status as sole ruler.6

Thus the death of Vladimir was followed by multiple fratricide, three years of dynastic war, a further seven years of periodic armed conflict, then a decade of coexistence before the final resolution when just one ofVladimir's numerous sons - Iaroslav - was left alive and at liberty. We can (and scholars do) speculate as to how the succession in 1015 'should have' worked. For such speculations to have any value, we need to be reasonably confident of three things: (i) that we know the seniority of his sons; (ii) that we know Vladimir's own wishes; and (iii) that we know what in principle constituted dynastic propriety at the time. But we know none of these things. Even if we did, and even if we could thereby in theory extrapolate a system to which his sons were meant to adhere, their actions demonstrate that any notional system failed to function. For practical purposes no such system existed.

The next change of generations, on Iaroslav's death in 1054, was more orderly. Like Vladimir, Iaroslav allocated regional possessions to his sons. Unlike Vladimir - according to the Primary Chronicle - he specified a hierarchy of seniority both within the dynasty and between the regional allocations, and he laid down some principles of inter-princely relations. The chronicle presents Iaroslav's arrangements in the form of what purports to be his deathbed 'Testament' to his sons, though it is possible that the document itself was composed retrospectively.7

6 Franklin and Shepard, The Emergence of Rus, pp. 183-207. The precise course of events is contentious: see e.g. I. N. Danilevskii, Drevniaia Rus' glazami sovremennikov i potomkov (IX-XIIvv.) (Moscow: Aspekt Press, 1998), pp. 336-54; A. V Nazarenko, Drevniaia Rus' na mezhdunarodnykhputiakh. Mezhdistsiplinarnye ocherki kul'turnykh, torgovykh, politicheskikh sviazei IX-XIIvekov (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul'tury, 2001), pp. 451-503.

7 Povest' vremennykh let (hereafter PVL), ed. D. S. Likhachev and V P. Adrianova-Peretts, 2 vols. (Moscow and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1950), vol. I, p. 108. See Martin Dimnik, 'The "Testament" of Iaroslav "the Wise": A Re-Examination', Canadian Slavonic Papers 29 (1987): 369-86.

As at the death of Vladimir, the offspring of older sons who had pre-deceased their father were not part of the general share-out. Seniority was lateral before it was vertical: that is, it passed down the line of sons before it passed to grandsons. However, whereas in 1015 Polotsk had remained with the family of Vladimir's deceased son, in 1054 Novgorod - the seat of Iaroslav's first son, who had died in 1052 - was not alienated as patrimony but reverted to being in the gift of the prince of Kiev. The oldest of Iaroslav's surviving sons in 1054 were given towns in the middle Dnieper region. Iziaslav and Sviatoslav were to have Kiev and Chernigov (still the two most desirable cities, as in the arrangement between Iaroslav and Mstislav thirty years before), while the third son, Vsevolod, was given the more precarious prize of Pereiaslavl', further south and more exposed to the steppes. As for the conduct of family business, the 'Testament' made two stipulations: first, the eldest son (Iziaslav) was to take the place of the father, was owed the same respect and had similar responsibility for resolving disputes; and second, the territorial allocations were to be inviolate, with no brother entitled to transgress the boundaries of another.

Iaroslav's 'Testament' dealt with an immediate problem of succession, but in the larger dynastic context over time it had to be more aspirational than operational. It only dealt explicitly with a small number of regions. It said nothing about subsequent succession. It was vague about the potential contradiction between its two principal instructions: that the oldest brother had a father's authority, yet that all the brothers' allocated possessions were inviolate (were Chernigov and Pereiaslavl' now the patrimonial possessions of Sviatoslav and Vsevolod respectively, or did Iziaslav have the right to reallocate as a father might?). And of course the 'Testament', like any document, could only be as effective as it was allowed to be by interested parties. Iaroslav's sons do seem to have operated as a reasonably harmonious triumvirate for nearly twenty years (briefly disrupted in 1067-8 when a kinsman from the Polotsk branch of the dynasty, Vseslav Briacheslavich, was installed as prince of Kiev by a faction of the townspeople). Yet in 1073 the two younger brothers, Sviatoslav and Vsevolod, blatantly contravened the provisions of their father's 'Testament' by ousting Iziaslav themselves. Iziaslav returned to Kiev after Svi- atoslav's death in 1076, only to be killed in 1078 in battle against a nephew, one of Sviatoslav's sons. Despite the dynastic messiness of Iziaslav's last few years, the result was neat. Kiev passed laterally down the line of brothers and Vsevolod at last found himself in a position similar to that of his father Iaroslav in the mid-i030s: with all his male siblings dead, he was left as 'sole ruler'. The 'Testament' of Iaroslav, blueprint for collective governance, was seemingly dissolved into monarchy. As we shall see, however, in the intervening period the dynasty had developed, and its complexities cannot be reduced to the struggle for Kiev alone.

The next change of generation, on Vsevolod's death in 1093, illustrated and affirmed an important feature of dynastic convention. Vsevolod was succeeded as prince of Kiev by Sviatopolk Iziaslavich. Seniority did not, therefore, pass directly from Vsevolod to his offspring, but reverted to the offspring of his older brother. Or rather, it reverted to the offspring of the oldest of his brothers who had been prince of Kiev (the general practice was that one could only succeed to a throne where one's father had already been prince - so those whose fathers died young were at risk of falling off the ladder of succession). Three principles thus emerge: (i) legitimacy in general resides with the dynasty as a whole; (ii) seniority passes laterally down the line of brothers, and then back up to the offspring of the senior brother, except that (iii) a prince of Kiev should be the son of a prince of Kiev (according to the chronicles' formula a prince 'sits on the throne of his father and grandfather').