PART III

*

RUSSIA UNDER THE FIRST ROMANOVS (1613-1689)

The central government and its institutions

MARSHALL РОЕ

For the Muscovite state, the seventeenth century was one of evolution and growth, rather than radical change.[1] The century experienced no political revolutions of the magnitude seen during the reigns of Ivan III and Ivan IV. Russia, having recovered from the confusion of the Time of Troubles, remained a strong autocracy held firmly in the hands of a small, martial ruling class. This is not to say that there was general stasis. Things still fell apart, though only for brief moments. And one can detect a single important political trend - the remarkable inflation of honours begun under Tsar Aleksei (Alexis) Mikhailovich and radically amplified by his weak successors. Nonetheless, the general picture was one of continuity, punctuated by momentary fits of confusion and gradual change.

The case is much the same in the realm of institutions.[2] Seventeenth-century Muscovy was administered by the same fundamental types of organisation that it had been before the great upheaval ofthe beginning ofthe century. The most important institutions remained the royal family, its court and courtiers (gosudarev dvor) and the administrative chancelleries (prikazy). Similarly, the boyar council and the Assembly ofthe Land-both inventions of an earlier age - continued to operate in the seventeenth century much as they had before. All of these institutions grew, but not so much as to fundamentally alter their essential character.

Finally, we might note that the state existed for the same purpose as it had in the sixteenth century and earlier - to serve the interests of the Muscovite ruling class.[3] Though one occasionally finds biblical tropes in Muscovite ornamental texts about monarchs 'tending their flocks' and such, the truth is that the elite did not hide the fact that they were a self-interested ruling class and that the state was the instrument of their domination. They showed open contempt for peasants, merchants and often clergymen, and almost never missed an opportunity to fleece them - a point made and bemoaned by the well-travelled, well-educated and well-informed political philosopher (and proto-Slavophile!) Iurii Krizhanich in the 1660s.4 Any attempt at protest that was not couched in the most subservient terms was met with a rush of horrific violence (violence that only the state could muster, since it was the only organised interest in early modern Russia). As visiting foreigners often noted, there was no talk of the 'commonwealth', the 'common good', or common anything (that would come with Peter and from Europe). Muscovites high and low believed the tsar owned everything - land and those occupying it - by heavenly proclamation.5 That he distributed his largesse unequally (and predominantly to the elite) bothered not a soul. No one could conceive of any other order, no one objected to it (at least for very long . . .) and no one even thought it wrong. It was the way of things, and that was that.

The tsar in his court

Muscovites had an entire catalogue of sayings to the effect that the tsar was like God (and, one might add, the God of Moses rather than Jesus),[4] so it is only appropriate that we begin our survey of seventeenth-century institutions with the ruler and his court.

Let us begin with the royal person, for he was an institution in his own right. In contrast to some monarchies, the Russians do not seem to have recognised or even known about the 'king's two bodies' doctrine.7 The clergy said and commoners believed that the tsar was selected by the Lord, not to hold the office of tsar, but to be tsar. This is why one finds so much talk of the 'true tsar' and 'pretenders', particularly during the Time of Troubles when it was hard to tell the difference, but also after the ascension of the Romanovs.8 Just how one could know the 'true tsar' was anybody's guess, but that there was a 'true' - that is, divinely appointed - tsar was never seriously questioned. There was, then, no office of'tsar'; there was just the 'true tsar', a person and family ordained by the hand of the All Mighty.

We know, of course, that Michael Romanov was elected or, rather, his family won out in a rough and tumble competition dominated by occupying cossacks in 1613. But it was not considered polite (or even safe)[5] to mention this after the fact. That is because Michael was the 'true tsar'. His family and their propagandists spent a lot of effort to drive this point home. They went so far as to argue that they were not only the very descendents and rightful heirs to the Riurikids (via one of Ivan IV's marriages), but that they were in some mystical sense Riurikids themselves. This effort to cloak themselves in other-worldly divinity appealed to the Muscovite mind, but it doubtless had little effect on the men who actually engineered the Romanov 'succession'. They knew, as politicians always know, what had actually happened. Nonetheless, it made no sense for them to do anything but play along. The tsar, after all, was one of them and would - if he were wisely selected - protect their interests. Michael and his successors did just this, and they became 'true tsars' as a result.

Though one reads occasionally in Muscovite didactic texts that the tsar should do this or that (take council, be merciful, be wise),[6] he really had only two hard and fast duties: to produce a suitable heir and to rule the country in consultation with his boyars. There were, naturally, rules about how he would perform these two tasks, the former governed by Christian doctrine and the latter by custom. Since the rights and obligations of Orthodox marriage are

Duma ranks

Boiare <

t

Okol'nichie -4— t

Dumnye dvoriane <

' t . Ceremonial ranks <

| n |

| >Dumnye d'iaki |

|

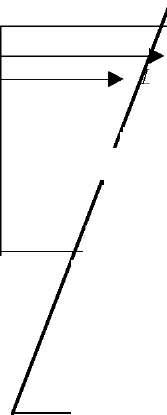

| Figure 19.1. The sovereign's court in the seventeenth century |

sufficiently well known (one wife, or at least one at a time), as is the process by which an heir is begotten, let us discuss the rules of Muscovite politics as they were practised in their principal arena, the sovereign's court (gosudarev dvor).11

The sovereign's court was the locus of political power in Muscovy. It was not a place (though the royal family did have quarters in the Kremlin called a 'court' or dvor), but rather a hierarchy of ranks. Figure 19.1 outlines them.

As one would expect, higher ranks were more honourable than lower ranks, and generally less populous. To some degree, different rank-holders did different things: the men in the duma ranks (boiare i dumnye liudi) advised the tsar in the royal council (duma), an ill-defined customary body whose power waxed and waned depending on the age of the tsar, the authority of those around him and the number of counsellors present. Those below the duma ranks (the sub-duma court ranks in Figure 19.i) generally worked as footmen of various sorts at court - serving at table, guarding the palace, performing in ceremonies, escorting emissaries and so on. Despite their modern 'servile' connotations, these lines of employ were considered very honourable duty by high-born Muscovites (and certainly better than serving in the provinces). Finally, the administrators served in the chancelleries (prikazy). Because they performed servile work (writing), they were drawn from a less honourable class (sluzhilyeliudipopriboru, or 'service people by contract') rather than from the ranks of hereditary servitors (sluzhilye liudi po otechestvu, or 'service people by birth').[7]

As Figure 19.1 suggests, servitors sometimes moved through the ranks. The rules for entry into and promotion through the upper ranks were as follows.[8]The men in the three duma ranks above dumnyi d'iak (boiarin, okol'nichii, dumnyi dvorianin) were generally recruited from hereditary servitors in the sub-duma court ranks. Elected hereditary servitors could be appointed to any of these three ranks (that is, not dumnyi d'iak). Once they had assumed a rank, they could progress upward, for example, from dumnyi dvorianin to okol'nichii or from okol'nichii to boiarin. Ranks could not be skipped after entry - one could not go directly from dumnyi dvorianin to boiarin. Dumnye d'iaki were generally recruited from the ranks of d'iaki who were themselves recruited from clerks (pod'iachie), all of whom were men of lower birth.[9] Like their hereditary counterparts in the duma cohort, they could progress through ranks after appointment, again, without skipping.

To simplify a bit, the game of Muscovite politics had as its goal either advancement to the high ranks (for individuals and their families) or control of the composition of these ranks (for the royal family, or blocs of allied families). It bears mentioning that seventeenth-century politics had very little to do with policies and everything to do with persons. There may have been debate on this or that issue, but, as we have noted, everyone in the sovereign's court was (to continue our metaphor) on the same team and pursued the same goal - the maintenance and, if possible, the expansion of the elite's interests.15 Certainly there was conflict over issues. But it is telling that the Muscovites never developed a formal institution that might represent differing political agendas among notables. None was needed. The prime political question, it appears, was always who would pursue this common agenda, and only rarely whether it should be pursued.

There were, in essence, three players in this contest.[10] First, there was the tsar himself. In theory, he made all appointments to and promotions through the ranks. Yet in fact he did not rule alone, but rather with the aid of close relatives, advisers and mentors.[11] The existence of a small retinue of advisers around the tsar was recognised by the Muscovites themselves: Grigorii Kotoshikhin, the treasonous scribe who penned the only indigenous description of the Muscovite political system, explicitly calls them the 'close people' (blizhnie liudi).[12] These confidants would and could bend the tsar's ear when it came to appointments and promotions. The second major class of players at the Muscovite court were old elite servitors, that is, men of very high, heritable status whose families traditionally held positions in the duma ranks. These were Muscovy's aristocrats: for centuries, they had commanded Muscovy's armies, administered Muscovy's central offices, and governed Muscovy's far- flung territories.[13] Their right to high offices was guarded by mestnichestvo,

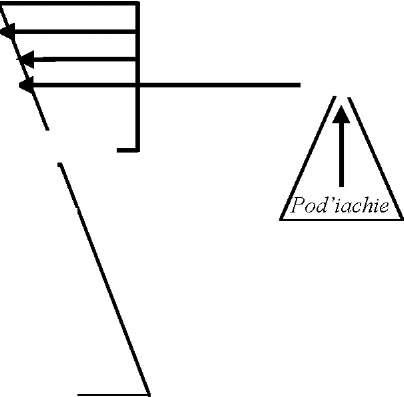

The tsar and his retinue

| 4fil, |

| Lower-status courtiers |

| [2,000 men/1,000 families] Stolfniki Dvoriane moskovskie Striapchie Zhil'tsy |

| D'iaki |

| Administrative class |

| Figure 19.2. The sovereign's court (c.1620) |

[2-4 f/milies]

The traditional elite

[30 m/n/20 faMies]

Boyars Okol'nichie

)umnye dvoriane Dumnye d'iaki

Younger members of the old\lite

early Russia's mechanism for protecting the order of precedence.[14] Finally, we have men and families serving in the lower orders of the sovereign's court - the thousands of stol'niki, dvoriane moskovskie, and striapchie who occupied minor offices in Moscow and the provinces. They could never reasonably hope to win appointments to the duma. Figure 19.2 describes the three interest groups within the system of ranks.

The contest over the duma ranks was not a fair one. The tsar held the most power - he, as we have said, made all the appointments. The old elite had considerable though less power - by Muscovite tradition, elite families had a special claim on the upper ranks, often passing them on through several generations. And the mass of courtiers had the least power - only very occasionally would the tsar reach down into the lower rungs ofthe court to elevate a common stol'nik, but the possibility was always open.

Each of these parties deployed different strategies to gain victory. The tsar's course was one of balance: he attempted to distribute just enough of the ranks to elite servitors so as to guarantee their allegiance, while at the same time reserving a portion for the purposes of patronage, reward of merit, or some

other end. Members of the old elite pursued a strategy of maintenance: they fought to preserve their hold on the duma ranks by keeping new servitors out ofexisting positions and preventing the tsar from creating new posts. The common courtiers' strategy was offensive: they used a variety of mechanisms to win favour with the tsar or elite (service, marriage alliances, etc.) in order to gain a place among the duma men.

Who won? A brief overview of seventeenth-century high politics

As Michael Romanov ascended the throne in 1613, he and the coalition of forces that supported him faced serious difficulties. There were several claimants to the crown (some arguably more legitimate than Mikhail Fedorovich), the country was occupied by Swedes, Poles and numerous rebel bands, and the economy was in shambles after many years of bloody civil war. No one was really sure who the 'true tsar' was. The Romanov party did the only thing it could to maintain power: issue a 'national' call to eject the foreigners, declare a de facto amnesty to those in other camps and begin the slow and painful process of reducing its opponents - alien and domestic - one at a time. First, the rebels were defeated (Zarutskii, Mniszech), then the otherwise distracted Swedes were pacified (the Treaty of Stolbovo, 1617) and finally the Poles were ejected (the Truce of Deulino, 1618). These measures shored up the Romanovs' hold on power. The return of Michael's father, soon-to-be Patriarch Filaret, from Polish captivity in 1619 solidified it. For the first and last time in Russian history, father and son - the head of the Church and head of the state - ruled together.

Aside from this single (albeit dramatic) innovation, the diarchy pursued a moderate course aimed at cultivating political support and recouping the considerable losses incurred during and after the Troubles. Even after the situation had stabilised, there was no general purge of elements who had fought for the 'wrong' side in the previous decades (though the Romanovs did turn hard on their former allies the cossacks). Rather, the sins of the Time of Troubles were forgotten for all but a few. The old boyars returned to their high places, irrespective of what port they had sought in the storm of the Troubles. The administrative class took its station as well, again without suffering for its prior allegiances. And the central and provincial military servitors were prepared for the imminent reckoning with Poland, which finally came in 1634.

Indeed, after the Romanov political settlement, Russian high politics were marked by a general peace for over thirty years. Certainly there were intrigues,

schemes and plots (many of which are unknown to us, hidden by the habit of not writing anything of importance down), but these were the quotidian affairs of every court in every country. The political quiet was shattered, finally, in 1648. Three years earlier, the young Aleksei Mikhailovich succeeded his much venerated father (see Table 19.1). Alexis's former tutor, Boris Ivanovich Morozov, became regent and packed the court and council with his cronies. Though a capable man, he was surrounded by the corrupt Miloslavskii clique (Alexis's first wife was a Miloslavskii; Morozov married her sister, thereby becoming the tsar's brother-in-law). Calls of government corruption grew louder until Moscow and several other cities exploded in riots aimed at bringing Morozov and the Miloslavskiis down. The mob lynched officials, burnt houses and looted shops. At one point, the tsar himself was threatened by the angry crowd. By all reports, this episode had a powerful effect on the youthful, pious ruler.[15] Bowing to pressure, Morozov and the tsar's father-in-law were exiled (only to return shortly), corrupt officials (or at least those the crowd said were corrupt) were brutally executed and the tsar resolved to reform the state in such a way as to make sure such things never happened again.

Alexis turned to the able Prince N. I. Odoevskii for help. He headed a commission designed to solve all the unattended problems faced by Muscovy at one bold, legislative stroke. Perhaps recalling his father's fondness for public input (it had saved them in 1613), Alexis called a massive assembly of 'all kinds of people' in Moscow for this purpose. In hindsight, it was a risky move for an immature leader still reeling from his first taste of popular protest. But the commission did its monumental work, the public acclaimed it, and Muscovy had a roadmap to permanent order - the Sobornoe Ulozhenie of 1649, one of the largest law codes of the early modern period. Like all successful compromises, there was something in it for everyone (or at least everyone who mattered): the powerful had their places next to the tsar affirmed; the gentry received the right to pursue runaway serfs and slaves as long as necessary to return them; and the common urban folks were promised that the corruption would be punished to the fullest extent of the law (which was, we should note, quite far).22 Again, peace reigned at court and in the country. Save two periods of

Table 19.1. The early Romanovs

Roman Iur'evich Zakhar'in

| Nikita |

| Anastasiia |

IVAN IV d. 1584

| FEDOR r. 1584-98 |

| Fedor (Patriarch Filaret) d. 1633 |

| ..m. (2) Natal'ia Naryshkina |

MICHAEL r. 1613-45

ALEXIS m. (1) Mania Miloslavskaia . r. 1645-76

| IVAN V r. 1682-96 |

| FEDOR r. 1676-82 |

Sophia Regent, 1682-9

PETER I ('the Great') r. 1682-1725

urban unrest brought on by debasement of the silver with copper (1656 and 1662), all was quiet. Or so it appeared. Under the calm surface, however, an important struggle was occurring at the very heart of Muscovite high politics.

The greatest cause of Alexis's reign (and his greatest triumph) was the Thirteen Years War, his effort to recoup the losses suffered at the hands of the hated Poles. Personally marching off to battle in 1654, he took a direct interest in making sure his crusade was brought off successfully. In the course of his campaigning, Alexis must (and here we are speculating) have judged for himself the merits (and demerits) of his soldiers, for he came back to the capital devoted to the idea of reforming, if not overturning, the existing political order.[16] In the context of a rapidly evolving administrative and military situation, the traditional boyar elite had become distinctly less useful. Even men of low status did not respect them, as Kotoshikhin's unflattering portrait demonstrates.24 Talented men - regardless of birth - who were willing to serve and serve well were needed. Given the rules of appointment to the boyar ranks, such 'new men' had no chance to attain the highest honours. Merit was not being rewarded, at least not in the way Alexis believed it should be. Obviously, the rules had to be changed so as to allow the entry of the 'new men'.[17]

The tsar did not bring the 'new men' into the duma all at once. He could not do so without risking a costly and dangerous political battle with the old elites. Rather, he pursued a conservative approach, appointing a few 'new men' at time. But even here his options were limited by the hold of the old elites over the upper ranks. Alexis knew that they would probably grumble if he promoted men oflower status to the highest ranks in the duma orders, forthese were the traditional preserve of the old elite. Neither could Alexis make the more honourable of the 'new men' conciliar secretaries (dumnye d'iaki), for that rank was deemed too low for the hereditary servitors in the sovereign's court. Therefore Alexis opted for a strategy that would at once appease the hereditary boiarstvo and permit him to promote the 'new men': he transformed the rank of conciliar courtier (dumnyi dvorianin). The chronology of events is telling. In 1650, Alexis took the unprecedented step of appointing a fifth man to dumnyi dvorianin. Prior to that act, the largest number of dumnye dvoriane had been four (in 1634 and 1635), and ordinarily there had only been one. By the first year of the war, there were eight of them. During the war, he promoted sixteen more. Among them we find many of Alexis's 'new men'.[18] During the war the tsar began to promote his dumnye dvoriane into the ranks of okol'nichie.27 One of them, A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin, was made boyar in 1667 and served as effective prime minister until 1671. In that year another 'new man', A. S. Matveev, took his place, though he was not promoted to boyar until 1674.28

Under Alexis, then, two prominent 'new men' came to rule Russia. Others exercised less visible but no less important roles as leaders in the chancellery system. In all, Alexis appointed forty-eight low-status 'new men' to the duma ranks. As we can see in Figure 19.3, the tsar entrusted them with a great number of Muscovy's highest administrative offices.[19]

Particularly notable is the fact that Alexis placed his 'new men' in the most important prikazy: the Military Service Chancellery (Razriad), arguably the most powerful prikaz in seventeenth-century Muscovy; the Service Land Chancellery (Pomestnyi prikaz), which administered estates given to the gentry throughout Russia; and the Ambassadorial Chancellery (Posol'skii prikaz), which controlled Muscovy's foreign affairs.30

Alexis began the process of supplementing hereditary rank-holders with competent 'new men'.[20] It is difficult to overestimate the impact of these appointments on the Muscovite political system. Alexis's alteration of duma appointment policy destroyed the equilibrium between the tsar and the elite families that ended the Time of Troubles. By the end of the Thirteen Years War, the tsar clearly had the upper hand in political matters. Alexis had successfully transformed the duma ranks from a royal council controlled by hereditary clans into a fount of royal patronage to be distributed as the tsar desired. The

DD > DDv > Ok > B

1646 1650 1655 Service Land [1643/4-63/4] 1646 Tsar's Workshop [1635 / 6-46 / 7]

1647 Grand Treasury [1630/1-46/7]; Ore [1641/2]; Ambassadorial [1646/7-47/8]

1648 Grand Revenue [1648 / 9-51 / 2]

1649 1664 Military Service [1648/9-63/4];

Monastery [1667/8-75/6]; New Tax District [1676/7] Kazan' Palace [1646/7-71/2]; Ambassadorial [i652/ 3-64/5]; Novgorod Tax District [1652/3-64/5]; Seal [1653/4-63/4]; Provisions [1674/5] 1655 Equerry [1646 / 7-53 / 4]

Patriarch's Court [1641/ 2-46/7, 1648/9-52/3]

Great Treasury [1634/5-61/2]; Ore [1641/ 2]

1653 Treasury [1639/40-44/5]; Ambassadorial

[1645/6-66/7]; Novgorod Tax District [1645/6-63/4]; Seal [1653/4-68/9]; Monastery [1654/5]; Seal Matters [1667/8]

Investigative [1654/5-56/7] NONE

Moscow (Zemskii) [1655/6-71/2]; Kostroma Tax District [1656/7-70/1]; Financial Investigation [i662/3-64/ 5] Moscow Judicial [1630/1-31/2]; Grand Revenue [1632/3-37/8]; Artillery [1658/9-62/3,1672/3-77/8]; Grand Treasury [1663/4-68/9]

1658 i665 i667 Ambassadorial [i666/7-70/ i]; Vladimir Tax District [1666/7-70/1]; Galich Tax District [1666/7-70/1]; Little Russian [1666/7-68/9]; Ransom [1667/8]

| Name |

| Baklanovskii, I. I. |

| O.-Nashchokin, A. L. |

| Anichkov, G. M. |

| Pronchishchev, A. O. Eropkin, I. F. Elizarov, P. K. |

| Kondyrev, Z. V Ianov, V. F. |

| Matiushkin, I. P. |

| Ivanov, A. I. |

| Elizarov, F. K. Anichkov, I. M. Chistoi, N. I. |

| Narbekov, B. F. Zaborovskii, S. I. |

| Lopukhin, L. D. 1651 1667 |

| 1655 1655 |

| 1655 |

| Ranks |

| Chancelleries led |

1659 Grand Palace [1657/8-64/5]; Palace Judicial [i664/ 5]; New Tax District [1664/5-68/9]

Figure 19.3. Alexis's new men in the chancelleries

| Ranks |

| Name |

Chancelleries led

DD > DDv > Ok > B

Pronchishchev, I. A. 1661

Leont'ev, Z. F. 1662

Chaadaev, I. I. 1662

Nashchokin, G. B. 1664

Khitrovo, I. T. 1664

Bashmakov, D. M. 1664

Karaulov, G. S. 1665

Durov, A. S. 1665

Khitrovo, I. B. 1666 1674

O.-Nashchokin, B. I. 1667

Grand Treasury [1661/2-62/3]; Monastery [1664/5]; Grand Revenue [1667/8-69/70]; Ransom [1667/8-69/70]; Criminal [1673/ 4-74/ 5] NONE

Moscow (Zemskii) [1672/3-73/4]; Foreign Mercenaries [1676/7-77/8]; Dragoon [1676/7-86/7]; Siberian [1680/1-82/3] Vladimir Judicial [1648/9]; Slave [1658/9-61/2]; Postal [1662/3-66/7] NONE

Tsar's Workshop [1654/5]; Grand Palace [1655/6]; Privy Affairs [1655/6-63/4]; Lithuanian [1657/ 8]; Ustiug Tax District [1657/ 8-58/ 9]; Financial Investigation [1662/3]; Military Service [1663/4-69/70, 1675/6]; Ambassadorial [1669/70-70/1]; Vladimir [1669/70-70/1]; Galich [1669/70-70/1]; Little Russian [1669/70-70/1]; Petitions [1674/5]; Seal [1675/6-99/1700]; Treasury [1677/8-79/80,1681/2]; Investigative [1676/7,1679/80]; Financial Collection [1680/1]

Service Land [1659/60-69/70]; Grand Palace [1669/70]; Postal [1669/70-71/2]; Kazan' [1671/2-75/6]; Moscow (Zemskii) [1679/80]; Criminal [1682/3]; Investigative [1689/90] Postal [1630/1-31/2]; Equerry [1633/4]; Grand Revenue [1637/ 8-39/40]; Musketeers [1642/3-44/5,1661/2-69/70]; Ustiug Tax District [1653 / 4, 1669/ 70-70/ 1]; New Tax District [1660/1-61/2]

Grand Palace [1664/5-69/70]; Palace

Judicial [1664/ 5-69/ 70]

NONE

Figure 19.3 (cont.)

| Ranks |

| Name |

Chancelleries led

DD > DDv > Ok > B

Tolstoi, A. V. Rtishchev, G. I. Ivanov, L. I.

Titov, S. S.

Solovtsov, I. P. Sokovnin, F. P.

| 1669 |

| 1670 |

| Dokhturov, G. S. 1667 |

| Golosov, L. T. 1667 |

| 1670 1670 |

| 1670 |

Nesterov, A. I.

Patriarch's Court [1652/3-58/9, 1660/1-62/3]; Ambassadorial [1662/3-69/70,1680/1]; Novgorod [1662/3-69/70,1680/1]; Ransom [1667/ 8]; Tsarina's Workshop [1659/60-60/1]; Vladimir [1667/8-69/70, i680/ i]; Galich [i667/ 8-69/ 70, i680/ i]; Little Russian [i667/ 8-69/70, i680/ i]; Pharmaceutical [1669/70-71/2]; Smolensk [i680/ i]; Ustiug [i680/ i] Postal [1649/50-51/2]; Grand Palace [1651/2-53/4]; Musketeers [1653/4-61/2]; Grand Treasury [1661/2-63/4]; New Tax District [1664/5,1666/7,1669/70-75/6]; Ambassadorial [1666/7-69/70]; Vladimir Tax District [i667/ 8-69/ 70]; Galich Tax District [1667/8-69/70]; Novgorod Tax District [1667/8-69/70]; Little Russian [1667/8-69/70]; Seal [1668/9-75/6]; Service Land [i669/70-75/ 6]; Military Service [1673/4-75/ 6]; Ransom [1677/8] NONE

Tsar's Workshop [i649/50-68/9] New Tax District [1662/3-63/4]; Grand Palace [i663/4-69/ 70, i680/i]; Armoury [1663/4-69/70]; Musketeers [1669/70-75/6,1677/8]; Ustiug Tax District [1672/3-75/6,1679/80]; Lithuanian [1674/5]; Investigative [1675/6]; Ambassadorial [1675/6-81/2] Musketeers [1655/6-56/7]; Vladimir Tax District [1655/6-56/7]; Galich Tax District [1655/6-56/7]; Criminal [1656/7]; Military Service [i657/ 8-58/ 9, 1669/70-73/4]; Financial Collection [1662/3-63/4]; Grand Palace [1663/ 4-69/70]; Vladimir Judicial [1663/4] Provisions [1669/70-70/1] Tsarina's Workshop [1666/7-69/ 70, 1676/7-81/2, 1681/2]; Petitions [1675/6] Gun Barrel [1653/4,1655/6,1657/8, 1660/1, 1665/6]; Armoury [1659/60-67/8]; Gold Works [1667/8]

Figure 19.3 (cont.)

Name Ranks Chancelleries led

DD > DDv > Ok > B

Matveev, A. S. 1670 1672 1674 Little Russian [1668/9-75/6];

Ambassadorial [1669/70-75/6]; Vladimir Tax District [1669/70-75/6]; Galich Tax District [1669/70-75/6]; Novgorod Tax District [1669/70,1671/2-75/6]; Ransom [1670/1-71/2]; Pharmaceutical [1671/ 2-75/ 6]

Leont'ev, F. I. 1670 Artillery [1672/3-76/7]

Khitrovo, I. S. 1670 1676 Provisions [1667/ 8-69/70]; Ustiug Tax

District [1670/1-71/ 2]; Monastery [1675/6-77/8]; Judicial Review [1689/90] Poltev, S. F. 1671 Dragoons [1670/1-75/6]; Foreign

Mercenaries [1670/1-75/6]

Naryshkin, K. P. 1671 1672 1672 Ustiug Tax District [1676/7]; Grand

Treasury [1676/7-77/8]; Grand Revenue [1676/7-77/8]

Grand Palace [1669/70-78/9]; Court Judicial [1669/70-75/6,1677/8-78/9] Military Service [1656/7-60/1]; New Tax District [1660/1-65/6]; Ransom [1666/7, 1668/9, 1670/1-71/2]; Ambassadorial [1670/1-75/6]; Little Russian [1668/ 9-75/6]; Vladimir [1670/1-75/6]; Galich [1670/1-75/6]; Grand Treasury [1675/ 6-76/7]; Grand Revenue [1675/6-76/7] Privy Affairs [1671/2-75/6]; Provisions [1675/6-77/8]; Grand Revenue [1675/6]; Investigative [1675/6,1677/8]; Musketeers [1675/6-77/8,1681/2]; Ustiug Tax District [1675/6-77/8]; Judicial [1680/1]; Moscow (Zemskii) [1686/ 7-89/ 90]; Treasury [1689/ 90] NONE

Artillery [1655/ 6]; Foreign Mercenary [1656/7-57/8]; Grand Treasury [1659/60-63/4]; Grand Revenue [1662/3]; Privy Affairs [1663/ 4-71/ 2]; Grand Palace [1671/ 2-76/7]

Equerry [1653/4-63/4]; Gun Barrel

| Khitrovo, A. S. 1671 1676 |

| Bogdanov, G. K. 1671 |

| Polianskii, D. L. 1672 |

| Naryshkin, F. P. 1672 Mikhailov, F. 1672 |

| Matiushkin, A. I. 1672 |

| Lopukhin, A. N. 1672 |

| Panin, V. N. 1673 |

[1653/4]

Tsarina's Workshop [1669/ 70-76/ 7] NONE

Figure 19.3 (cont.)

tsar no longer ruled exclusively with the duma men, but instead via special conciliar and executive bodies. Kotoshikhin described two of them. The first was a kind of privy council chosen from the 'closest boyars and okol'nichie' (boiare i okol'nichie blizhnie). Here Alexis discussed affairs 'in private', outside the large council.32 Second, Kotoshikhin detailed the workings of the Privy Chancellery (Prikaz tainykh del), where the 'boyars and duma men do not enter . . . and have no jurisdiction'.33 And that chancellery', he wrote, 'was established in the present reign, so that the tsar's will and all his affairs would be carried out as he desires, without the boyars and duma men having any knowledge ofthese matters.'34 Kotoshikhin's understanding of Alexis's relation to hereditary duma men is clear: while he honoured them, he did his real business with the 'closest people'. He was, it is true, hardly the first Russian ruler to surround himself with an inner circle of powerful advisers.35 He was, however, the first to do so since the political settlement that ended the Time of Troubles. For one of the few times in Muscovite history, the tsar had succeeded in liberating himself from the elite of which he was a part. Muscovy became an autocracy - or at least less of an oligarchy - as it had been under Ivan III and Ivan IV.

But only for a moment, for Alexis's new order proved untenable. He was strong enough and clever enough to use his novel tool of patronage sparingly. His successors were neither. As a result of their political insecurity, Fedor, Sophia and young Peter -together with those who urged them on - were forced to 'go to the well' of duma patronage often in order to win support among the boiarstvo. They made hordes of appointments from the ever-expanding court in a desperate effort to curry favour. The result can be seen in Figure 19.4.

The duma ranks ballooned, and thereby lost their meaning even as royal patronage. Alexis's weak successors had, in essence, devalued the currency bequeathed to them by their father. What Alexis had carefully designed as a mechanism to bring new talent into the political class resulted, under his children, in the destruction of that class. Confusion reigned among the elite; mestnichestvo - a nuisance from the point of view of the crown and meaningless from the point of view of the old elite - died an unmourned death.36 As early

32 Kotosixin, ORossii,fo. 36.

33 Ibid., fo. i23v.

34 Ibid., fo.i24.

35 On the existence ofsuch 'inner circles' in previous eras, see A. I. Filiushkin, Istoriiaodnoi mistifikatsii: Ivan Groznyi i 'IzbrannaiaRada' (Moscow: VGU, 1998), and Sergei Bogatyrev, The Sovereign and His Counsellors. Ritualised Consultations in Muscovite Political Culture, 135os-157os (Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Science and Letters 2000).

36 Marshall T. Poe, 'The Imaginary World of Semen Koltovskii: Genealogical Anxiety and Falsification in Seventeenth-Century Russia', Cahiers du monde russe 39 (1998): 375-88.

| 40 | |||||||||

| J3 - | |||||||||

| 64 5 | |||||||||

| 87 | |||||||||

| 107 | |||||||||

| 143 | |||||||||

| .„ 1 | |||||||||

| , 139 | |||||||||

| 65 59 59 | |||||||||

| 50 41 | |||||||||

| 38 | |||||||||

| 38 | |||||||||

| 30 | |||||||||

| 31 | |||||||||

| 34 3U | |||||||||

| 3! | |||||||||

| 3S 39 3! 3! | |||||||||

| _ | |||||||||

| 3 3 | |||||||||

| 3! | 5 ™ | ||||||||

| 41 | |||||||||

| 3 | 7 ! | ||||||||

| UO[V JO ,|.М|ШП\ |

| 1712 1709 1706 1703 1700 1697 1694 1691 1688 1685 1682 1679 1676 1673 1670 1667 1664 1661 1658 1655 1652 1649 1646 1643 1640 1637 1634 1631 1628 1625 1622 1619 1616 1613 |

as 1681, even the wise old men of the traditional elite - led in this instance by Vasilii Golitsyn - were actively searching for a new order to replace what had obviously been broken.[21] They failed, and it would be up to Peter, who personally witnessed the corruption of his father's legacy, to forge a new and profoundly monarchical political system.

The chancelleries

While the boyar and court elite led Muscovy, chancellery personnel - the prikaznye liudi - administered it. They were, as we have seen, distinctly second- class citizens at court, 'employees at will' serving at the pleasure of the tsar - or not. But the state was growing rapidly in the seventeenth century, and with it the administrative burden of far-flung, complex operations. Since the prikaz personnel needed organisational skill and a deep knowledge of affairs, the elite generally kept them employed and reasonably satisfied - the state could not run without them. If a chancellery man performed well and had the proper connections, he could advance, first, through the administrative ranks (pod'iachii to d'iak) and, then, to the duma (though very rarely and almost always to dumnyi d'iak, no further). This cursus honorum was steep: only a small proportion of all clerks (pod'iachie) were made d'iaki (secretaries) and few d'iaki were made dumnye d'iaki.38 As we have noted, late in the century some of the prikaz people occupied important positions in the government, and one served as de facto prime minister. This remarkable shift upward was a reflection of the growing importance of administrative work for the state.

The world of the prikaz people was different from that of any other Muscovite in a number of ways. First, the chancellery employees were literate, a fact that differentiated them from even most members of the elite (Koto- shikhin called the latter 'unlettered and uneducated').[22] As the century drew to a close, a few of them would even develop a taste for something we might sensibly call 'literature' (almost all of it imported), a first for Muscovy.40 Second, the prikaz people worked in offices run in quasi-rational fashion. The chancelleries had many ofthe trademarks of the classic Weberian bureaucracy: written rules, regular procedures, functional differentiation, reward to merit.41 This is not, of course, to say that prikaz employees were insulated from the winds of nepotism, favouritism and even caprice. Far from it: most prikaz people were the sons of prikaz officials, all had patrons and not a few were summarily dismissed without cause. Nevertheless, the rudiments of the modern administrative office were all present in the prikazy. Finally, chancellery workers lived in Moscow cheek-by-jowl with the elite: the prikazy were located in the Kremlin and Kitai gorod and their employees lived in the environs. This proximity gave them access to power that was unimaginable for the typical Russian.

As the interests of the state expanded, so too did the ranks of the prikazy.[23]The number of prikaz people grew significantly in the seventeenth century, from a few hundred in 1613 to several thousand in 1689. The vast majority of them were lowly clerks (pod'iachie). These men did most of the work in the offices, and their numbers expanded mightily during the century: in i626 there were around 500 of them in the Moscow offices; by i698 there were nearly 3,000.[24] As in all Muscovite institutions, we find hierarchy among the clerks - junior (mladshii), middle (srednii) and senior (starshii). If a man were particularly lucky, he might be appointed to d'iak. D'iaki ordinarily commanded the chancelleries, serving together with an extra-administrative servitor (usually a man holding duma rank). They could be tapped for other services as well, as Kotoshikhin tells us: 'they [d'iaki] serve as associates of the boyars and okol'nichie and duma men and closest men in the chancelleries in Moscow and in the provinces, and of ambassadors in embassies; and they . . . administer affairs of every kind, and hold trials, and are sent on various missions.'44 Like the pod'iachie, the numbers of d'iaki grew in the seventeenth century: in i626 there were around fifty serving in the chancelleries; by i698, there were roughly twice that many.45 Of the roughly 800 men who served as d'iaki in the century, only forty-seven ever achieved the exalted status of dumnyi d'iak. These men were super-secretaries: they attended the royal council (though they were required to stand during the proceedings), advised the tsar, and administered the most sensitive affairs.46 Of them, thirteen achieved the rank of dumnyi dvorianin; four, okol'nichii; and one, boyar.47 Naturally, all of these men were advanced late in the century, after Aleksei Mikhailovich had 'opened the ranks to merit'.

The number of chancelleries themselves grew in the seventeenth century as well. In the ten years following the accession of Michael, the number rose from around 35 to around 50; thereafter, the number varied between 45 and 59.48 These figures are, however, misleading on a number of counts. First, most chancelleries were quite short-lived, reflecting the fact that they were often created on an ad hoc basis to fulfil a specific mission (for example, the collection of a tax, or the investigation of a particular affair). Only the largest chancelleries administering the most central functions - the Military Service, Service Land, the Ambassadorial and so on - operated continuously throughout the century.

Though the chancelleries were not officially arranged in any 'organisational chart', we can gauge their administrative scope by placing them in functional categories (see Figure 19.5: Numbers and type of chancelleries per decade, i6i0s-i690s).49 What is most apparent in Figure 19.5 is the concentration on military and foreign affairs - the prikazy were primarily instruments of war- making. Most of them were either directly engaged in provisioning the army (the military chancelleries, and we should include the Service Land Chancellery here as well) or funding the army (the financial chancelleries). Though

44 Kotosixin, O Rossii, fo. 37v.

45 Demidova, Sluzhilaia biurokratiia, p. 23.

46 Kotosixin, O Rossii, fos. 33ff.

47 See Poe, The Russian Elite in the Seventeenth Century, vol. 11, p. 35.

48 On all that follows concerning the prikazy, see Brown, 'Early Modern Russian Bureaucracy' and his 'Muscovite Government Bureaus'.

49 Peter B. Brown, 'Bureaucratic Administration in Seventeenth-Century Russia', inJ. Koti- laine and M. Poe (eds.), Modernizing Muscovy: Reform and Social Change in Seventeenth- Century Russia (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), p. 66. Sub-headings such as 'Manpower mobilisation' indicate areas of competence, and the numbers do not add up to the sub-totals above them.

| i6i0s i620s i630s i640s i650s i660s i670s i680s i690s | |||||||||

| CHANCELLERIES OF THE REALM | 44 | 50 | 48 | 47 | 50 | 54 | 51 | 40 | 46 |

| MILITARY AFFAIRS | i2 | 9 | i7 | i5 | i5 | i7 | i5 | ii | i5 |

| • Manpower | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| mobilisation | |||||||||

| • Weapons production | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| • Fortification | i | i | 2 | 2 | i | i | i | i | i |

| • Finance and supply | 4 | i | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| • Prisoner of war | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | i | 0 | 0 |

| redemption | |||||||||

| • Military administration | 2 | i | i | i | i | 2 | i | i | 2 |

| FINANCE | i2 | i2 | i0 | ii | ii | i2 | i2 | 9 | ii |

| • Taxation | ii | ii | ii | ii | ii | ii | ii | 9 | i0 |

| • Treasuries | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| • Minting | i | i | 0 | 0 | i | 2 | i | 0 | 0 |

| • Mining | 0 | 0 | 0 | i | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | i |

| SERVICE LAND | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i |

| FELONY PROSECUTION | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | 2 | i |

| FOREIGN AND | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| COLONIAL AFFAIRS | |||||||||

| • Diplomacy | i | i | i | 2 | i | 2 | i | i | i |

| • Southern and western | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| territories | |||||||||

| • Colonial | i | i | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| administration | |||||||||

| • Judicial instance for | i | i | i | 2 | 3 | 2 | i | i | i |

| foreigners | |||||||||

| POSTAL SERVICE | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i |

| URBAN AFFAIRS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | i | i |

| • Townsmen | i | i | i | 2 | i | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Moscow | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i |

| • Health statistics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | i | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| • Social welfare | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | i | i | 0 | 0 |

| LITIGATION | 7 | i0 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| • Petitioning | 2 | 2 | 2 | i | i | i | i | i | 0 |

| • Upper and middle | ii | i3 | 9 | 9 | 9 | ii | ii | ii | ii |

| service classes | |||||||||

| DOCUMENTS AND | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| PRINTED MATTER | |||||||||

| ECCLESIASTICAL | 3 | 2 | 0 | i | 2 | i | i | 0 | 0 |

| AFFAIRS | |||||||||

| MISCELLANEOUS | i | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | i | 2 | i | i |

| Figure i9.5. Numbers and type of chancelleries per decade, i6i0s-i690s | |||||||||

| PALACE | 10 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| CHANCELLERIES | |||||||||

| COURT AND ITS LANDS | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| CARE OF THE TSAR | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| PRECIOUS METALS AND OBJECTS | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| MEMORIAL SERVICES AND HISTORY | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PRIVY CHANCELLERIES OF THE TSAR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| ALEKSEI MIKHAILOVICH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PETER THE GREAT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| PATRIARCHAL CHANCELLERIES | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| TOTAL | 57 | 68 | 65 | 63 | 66 | 66 | 65 | 56 | 61 |

| Figure 19.5 (cont.) | |||||||||

| the foreign affairs chancelleries | were | fewer | in number, | one | ofthem | - the | mas- |

sive Ambassadorial Chancellery - was a locus of state power which controlled far-flung territories. Chancelleries in these categories were the largest, best funded, most powerful and most honourable of all the administrative organs in the central government.

Like the workaday lower-court nobility, the chancellery personnel grew more powerful during the course of the century for the simple reason that the tsar found their services increasingly indispensable. Modern states cannot operate without relatively efficient - or at minimum, effective - bureaucracies. They collect the taxes, recruit personnel, and organise complex affairs generally Throughout early modern Europe, states were travelling a road that made them more and more dependent on the offices of well-trained, skilled administrators. So it was in Muscovy By the close of the century, the status of both administrators and administrative work had risen appreciably More and more of them were elevated to the royal council, and increasingly hereditary military servitors of very high status (the old boyars and 'new men') opted to serve the tsar in the prikazy.50 The once entirely martial ruling class gained a hybrid character, working with near equal frequency in the court, army and

50 Robert O. Crummey, 'The Origins of the Noble Official: The Boyar Elite, 1613-1689', in D. K. Rowney and W M. Pintner (eds.), Russian Officialdom: The Bureaucratization of

offices. It was a common story, one that has parallels in Prussia, France and all other successful early modern states.51

Other central institutions: the 'boyar council' and 'Assembly of the Land'

The tsar, the court and the prikazy were the central stable elements of Muscovite governance throughout the seventeenth century. This being said, there were two other institutions, quite different in character, that we find in this era: the so-called 'boyar council' (boiarskaia duma) and Assembly of the Land' (zemskii sobor). Both have been the subject of considerable controversy. Early historians, with their eyes to the West, saw in them formal counselling and even representative bodies, the Russian analogues to peer councils and parliaments. Later historians called these views into question, noting that both terms were invented by eighteenth-century Russian historians and that there is very little in law or custom that defined the competence or operation of these bodies. With this in mind, let us look at what is known about these institutions today.

The phrase boiarskaia duma, though a later coinage, has come to stand for the regular high councils held at the courts of Kievan, apanage and particularly Muscovite princes from the ninth to the early eighteenth century.52 It appears in no medieval or early modern Russian source. The terms 'council' (duma), 'privy council' (blizhniaia duma) and 'tsar's senate' (tsarskii sinklit) appear in Muscovite sources and refer to a royal council of some sort. In early Muscovy, dependent service families, not princes or independent lords, staffed the council. Consistent with this fact, the council seems to have evolved into an

Russian Society from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), pp. 46-75. Also see Bickford O'Brien, 'Muscovite Prikaz Administration of the Seventeenth Century: The Quality of Leadership', FOG 24 (1978):

223-35.

51 On the All-European context, see Marshall T. Poe, 'The Military Revolution, Administrative Development, and Cultural Change in Early Modern Russia', Journal of Early Modern History 2 (1998): 247-73, and his 'The Consequences of the Military Revolution in Muscovy in Comparative Perspective', Comparative Studies in Society and History 38 (1996): 603-18.

52 The literature on the boyar elite (what we have called the duma ranks of the sovereign's court) is immense, while studies of the duma per se are few (largely due to a lack of sources). The standard treatments, all somewhat dated, are: V O. Kliuchevskii, Boiarskaia duma drevnei Rusi. Opytistoriipravitel'stvennogo uchrezhdeniiav sviazi s istoriei ohshchestva, 3rd edn (Moscow: Sinodal'naia tipografiia, 1902); S. F. Platonov, 'Boiarskaia duma - predshestvennitsa senata', in his Stat'ipo russkoi istorii (1883-1912), 2nd edn (St Petersburg: M. A. Aleksandrov 1912), pp. 447-94; V I. Sergeevich, Drevnosti russkogo prava, vol. 11: Vecheikniaz'. Sovetnikikniazia, 3rd edn (St Petersburg, 1908). The best modern treatment is Bogatyrev, The Sovereign and his Counsellors.

instrument of the prince's private administration (his 'patrimony' (votchina)). Officers of the domain ('chiliarchs' (tysiatskie)), 'major-domos' (dvoretskie), 'seal-bearers' (pechatniki), 'treasurers' (kaznacheia)) are identified among his counsellors. Classes appear among the boyars in the council early on: the 'privy boyars' (vvedennye boiare) and 'departmental boyars' (putnye boiare), for example, are distinguished from all others. These men were probably agents of the prince's private administration, but this is not certain. The competence of the council appears to have been extensive but is indistinguishable from that of the prince. No formal definition of powers is found in any source. Similarly, nothing is known of the internal operation of the council in the early period.

The princely council underwent considerable development in connection with the rise of Muscovy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. To the old Muscovite service families were added immigrants from defeated apanages, the Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Tatar khanates. These new arrivals were at first given minor positions in the grand-princely administration and later, after they had been tested, were given high court rank and served as councillors. Records of this era permit the identification of most of those holding these ranks, something impossible in the Kievan and Apanage periods.[25] The evidence suggests that the number of men holding 'conciliar ranks' (dumnye chiny) was small, hovering around fifteen members in the years of Ivan III and Vasilii III, though it increased in size to about fifty under Ivan IV In this period the competence of the duma - or at least of certain members of the council - is suggested in legislation and legal documents for the first time. The Law Code (Sudebnik) of 1497 directs that the 'boyars and okol'nichie are to administer justice' (suditi sud boiaram i okol'nichim), and it is known from surviving cases that they did so.54 In like measure, the duma seems to have had some legislative authority, as can be seen in the often-repeated Muscovite formula 'the sovereign orders and the boyars affirm' (gosudar' ukazal i boiare prigov- orili). Despite these hints, the exact boundaries of the duma's independent competence, if any, remained unregulated.

Towards the end ofthe sixteenth century foreigners provided some sketchy evidence of the operation of the council.55 They report seeing the council arrayed during ambassadorial audiences. However, it is evident that on such occasions the members played highly scripted roles that probably did not reflect the proceeding of 'private' council meetings. According to the English ambassador Giles Fletcher, central and provincial administrators, as well as private suitors, appeared before the duma on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays at seven in the morning.[26] The foreigners generally dismissed the duma as an ineffectual body, but this is not entirely accurate.[27] The council was very active during the Time of Troubles and succeeded in imposing an oath on Tsar Vasilii Shuiskii in 1606. According to Kotoshikhin, a similar oath was taken by Michael Romanov in 1613, but this is uncorroborated.58

In the seventeenth century, the competence of the council, as well as its exact composition and mode of operation, remained undefined - there was no constitution or even coherent (and inscribed) custom detailing who was (or should be) on it, or what it was to do (other than deliberate with the tsar). Kotoshikhin thoroughly describes general congresses of council members in which affairs were discussed and legislation was considered, affirmed and sent to the chancelleries for promulgation.[28] He tells us that 'although [Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich] used the title "autocrat", [he] could do nothing without the boyars' council'.[29] His son, in contrast, did quite a bit without their council. He favoured smaller groups of familiars (the blizhnie liudi) over the mass of courtiers who were coming to occupy the duma ranks.[30] By the second half of the century, the number of men who held these ranks was in all probability too large for all of them to serve as councillors, and there is no evidence that they did so. The duma ranks, as we have said, had turned into a source of patronage for weakmonarchs and thus the councillors - at least most of them - were deprived of their council.

The history of the zemskii sobor is just as controversial and murky.[31] The phrase itself was coined by the radical Slavophile Konstantin Aksakov around 1850.[32] It is found in no Muscovite source. Nineteenth-century Russian historians of a liberal bent tried their best to make out of the thin evidence a 'proto-parliamentary' body that - but for the unbridled power of self-seeking tsars and boyars - might have led Russia to enlightened liberal democracy. More sober historians, focusing on the evidence rather than projecting their fantasies on bygone eras, contradicted this rosy interpretation. The battle continues.

What can be said with confidence is this.[33] Some sort of popular assembly was first called by Ivan IV and, thereafter, occasionally by his successors. The regime of Michael Romanov-weakand attemptingto establishits legitimacy- seemed particularly fond of them (he was 'elected' by one), though his father was not. Though the assemblies (usually called sobory) could be assigned very specific tasks -for example, ratification ofthe Ulozhenie of 1649 (called 'Sobornoe' because it was affirmed by a sobor) - they were generally organised by the government to take stock of opinion on affairs domestic and international.

The composition of the assemblies was never set, though they appear to have had two salient characteristics-they were elite (almost entirely composed of high-born military servitors) and they were ad hoc (the government often simply gathered servitors and clerics already in Moscow). Some were large - several hundred delegates; others were small - several dozen delegates. The assemblies were not regularly conferred according to any schedule. Rather, they seem to have been called in moments of doubt or crisis. Delegates almost always supported the government; there was no forceful 'debate' as far as we know. Their exact competence - like the royal council - was never defined in law or custom, though they were consulted on a wide range of affairs. As we can see in Figure 19.6, some acclaimed tsars, others declared war, while others still adopted legislation.[34]

Delegates were called as a matter of service obligation (and sometimes viewed said service as onerous), not as a matter of 'right'. Neither in years

| Year | Primary activity |

| 1613 | Chose Michael as tsar |

| 1614 | Advised on stopping movements of Zarutskii and the cossacks |

| 1616 | Discussed conditions of peace with Sweden and a monetary levy |

| 1617 | Advised on a monetary levy |

| 1619 | Advised on raising of Filaret to the patriarchal throne |

| 1621 | Advised on war with Poland |

| 1622 | Advised on war with Poland |

| 1632 | Advised on the collection of money for the Polish campaign |

| 1634 | Advised on the collection of money and on the Polish campaign |

| 1637 | Advised on an invasion of the Crimean Khan Sefat Girey and the |

| collection of money | |

| 1639 | Advised on response to Crimean treatment of two Muscovite envoys |

| 1642 | Recommended support of Don cossacks in relation to the taking of |

| Azov | |

| 1645 | Chose Alexis as tsar |

| 1648 | Advised the composition of a new law code |

| 1648-9 | Approved the new law code |

| 1650 | Advised on the movement of people into Pskov |

| 1651 | Advised on Russo-Polish relations and Bohdan Khmel'nyts'kyi |

| 1653 | Advised on war with Poland and support of Zaporozhian cossacks |

| 1681-2 | Advised on military, financial and land reforms |

| 1682 | Chose Peter as tsar (27 April); chose Peter and Ivan as co-tsars (May) |

| 1683-4 | Advised on peace with Poland |

| Figure 19.6. Seventeenth-century 'Assemblies of the Land' and their activities |

without assemblies, nor in the year they were extinguished finally, was there any protest or even mention of them in Muscovite sources. Foreigners, who were often careful observers of Russian politics, very rarely note them and when they do attribute little importance to them.66

Concluding remarks

In the end, the seventeenth-century Muscovite state proved to be quite robust. Even after it was almost totally taken apart in the maelstrom of the Time of Troubles, the triptych tsar-court-prikazy re-emerged rapidly and in full form. The ruling class wasted no time or effort on costly government experimentation in 1613. It simply picked itself up and got down to business. And its business was rule, plain and simple. For the tsar, his court and the men of offices, the

66 Poe, A People Born to Slavery', pp. 66-7.

entire point ofthe state was to rule over others and live off them. Never was this point seriously questioned. One must admire the single-minded purpose this sort of concentration bespeaks. While other early modern states (whatever their form) might pursue any number of goals - fostering science, patronising the arts, educating the public, spreading the Good Word-the Muscovite elite focused nearly all its energy in ruling others or conquering others so that they might rule them. Domination was their raison d'etre.

As the century closed, this focus was, for good or ill, lost. Peter and his cohort were enamoured of a different vision of the state and its goals, one that was as new to Russia as it was profoundly alien to the Muscovite spirit. Aleksei Mikhailovich could no more have said he was the 'first servant of the state' than he could have sworn off the Orthodox faith. He could not serve the state because he owned the state. It was his instrument to do with as his master - God in Heaven - commanded. Neither could his servitors have said they were serving anything like the 'common good'. Such a thing was impossible, for they were honourable men and truly honourable men served only God and his representative, the tsar. As for the rest - all those who were neither tsars nor servants of tsars - they just did not matter.Local government and administration

BRIAN DAYIES

There were two important developments affecting local government in the period 1613-89. The first was the spread of the town governor system of local administration. In the sixteenth century annually appointed town commandants (godovye voevody) with some civil as well as military authority had been found in some districts on the southern and western frontier. But by the 1620s most districts were under commandants turned town governors (gorodovye voevody), with staffs of clerks and constables, and exercising authority over the guba and zemskii elders, fortifications stewards, siege captains and other local officials. Responsibility for most aspects of defence, taxation, policing, civil and criminal justice, the remuneration of servicemen and the regulation of pomest'e landholding at the district level was now concentrated in the town governors' offices. The second development was the increasing reliance of town governor administration on codified law, written instructions and regular reporting and account-keeping. This enhanced central chancellery control over local administration and partly compensated for the avocational nature of town governor service.

The spread of town governor administration

The universalisation of gorodovyi voevoda administration had been a response to the breakdown of the political order in the Time of Troubles. On the one hand, the spread of town governor administration across the southern frontier in the late sixteenth century had helped to fuel the Troubles: mass discontent with the heavy burdens of defence duty and agricultural corvee on the 'Sovereign's tithe ploughlands' had led to the overthrow of several southern frontier town governors and placed much of the south in the hands of the First False Dmitrii and successor insurgents. On the other hand, after the disintegration of Tsar Vasilii Shuiskii's regime in 1608 the tasks of defeating the rebels and foreign invaders and re-establishing strong central authority fell by default to other town governors, notably P. P. Liapunov of Riazan' and D. M. Pozharskii of Zaraisk, who had the military experience and political connections to lead the governors and lesser officials of the towns of the north-east into forming an army of national liberation and a provisional government. In coalition with certain boyars and cossack leaders Pozharskii's army drove the Poles from Moscow (1612) and restored the Russian monarchy under the new Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich (1613). It was natural that the new Romanov monarchy should see its continued survival in the utmost centralisation and militarisation of provincial government - the logical agents of which were the town governors, appointed by and accountable to the central chancelleries, selected from the court nobility, and given broad authority over district military, fiscal, judicial and police affairs. Upon Tsar Michael's accession his government was supposedly deluged with collective petitions from the provinces, 'from many towns, from the dvoriane and deti boiarskie and various servicemen and inhabitants', begging that town governors be placed in charge of their districts, for 'without town governors their towns would not exist'.[35] Whether these petitions really represented local will or its ventriloquism by the central government cannot be determined, but three days later the central government authorised the general restoration and expansion of town governor rule, to all districts in need of town governors. Whereas town governor administration had been confined mostly to the western and southern frontiers before the Troubles, it came to prevail throughout the centre and north as well by the 1620s. By 1633 there were 190 governors' offices, and 299 by 1682.[36]

After 1613 most of the local administrative organs common before the Troubles were liquidated or were absorbed into town governor administration. The title of vicegerent (namestnik) was still used at court as a ceremonial honorific, but vicegerents no longer governed in the provinces. The fortifications and siege stewards declined in number and became subordinate officials (prikaznye liudi) of the town governors' offices. Customs and tavern administration remained in the hands of elected community representatives or tax- farmers, but they came under the supervision of the town governors, who supervised their operations and gave them quarterly or annual accountings. District-level and canton-level elected zemskii offices for tax collection and justice continued to exist in the north, but most of them were subordinated to the town governors, so that zemskii officials no longer dealt with the chancelleries directly but only through their local governor; the more important kinds of court cases traditionally heard in the district-level zemskii court were now held in the governor's court, which also became a court of second instance over those matters still heard in zemskii courts; and the tax-collection activities of zemskii officials were subject to especially tight control from the governor's office, for the governor had the authority to beat zemskii officials under righter (pravezh), that is, in the stocks, for any tax arrears or irregularities and the tendency was towards requiring zemskii collections to be turned in to the governor's office.

For some time the guba constabulary offices for policing and investigating felonies were permitted greater autonomy, for Moscow saw some advantage in keeping the defence of the community against banditry and violent crime in the hands of elected community representatives - especially as those elected as chief constables were supposed to be the communities' 'best men', ideally prosperous dvoriane or deti boiarskie, reporting their investigations directly to the Robbery Chancellery (Razboinyi prikaz) at Moscow for pronouncement of verdict. Besides reducing the need to send down special inquisitors from Moscow, this would have the advantage of shifting blame for policing failures from state officials to community representatives. Moscow's preference for the continued independence of the guba system was indicated in the 1649 Ulozhenie and 1669 New Decree Statutes as well as in a 1627 decree that announced that guba chief constables should be elected in all towns. But this came up against fiscal and manpower concerns: maintaining guba offices cost the community additional taxes, and in wartime prosperous dvoriane and deti boiarskie were needed in the army, not at home performing constabulary duties which could be assumed by the town governors or, in worst cases, by inquisitors from the Robbery Chancellery. The guba system was therefore not expanded; the town governors increasingly sought to subordinate the guba officials de facto; and in 1679 all guba offices were closed.[37]

Enhanced control through improved record-keeping

Town governor administration operated under closer central chancellery control than had vicegerent administration in the previous century because the town governors' offices were held to higher expectations of written reporting and compliance with written instructions. The town governors were guided in their general or long-term responsibilities by written working orders (nakazy), and in more particular and non-routine matters by decree rescripts from the chancelleries; they were expected to submit frequent reports, even if all they had to relate was their progress in implementing relatively routine directives; and they had to maintain an increasingly wide range of rolls, inventories, land allotment and surveying books, court hearing inquest transcripts and account books for various indirect and direct revenues. Inventories of the archives of governors' offices generally show a significant increase in the rate of record production, especially from mid-century. This reflected the increasing demands upon the governors' offices by the central chancelleries, but also the demands upon them from the community in terms of litigation and petitioning of needs and grievances. [38]

Because the primary purpose of the governor's office was to gather and systematise information to facilitate executive decision-making in the central chancelleries and duma, the clerical staffing of the governor's offices was a crucial concern. It was the governor's clerks (pod'iachie) who produced, routed and stored all this information and kept order in the town archive and treasury. The clerks also performed important tasks in the field - supervising corvee, conducting obysk polling at inquests, conveying cash to and from Moscow, or surveying property boundaries. In some districts the governor's clerical staff was too small, too inexperienced or too poorly remunerated to maintain the flow of information required by the chancelleries. The smaller governors' offices might have only one or two clerks in permanent service and so be forced to turn over some tasks to public notaries or even press passing travellers into temporary clerical service. In the 1640s the clericate of the provincial governors' offices officially numbered no more than 775, slightly fewer than the number of clerks staffing the central chancelleries.[39] However, the total clerical manpower at work in provincial administration may have been significantly larger because this total does not include the clerks serving in the customs, liquor excise, guba and zemskii offices. Furthermore, the small clerical staffs of the smaller governorships could be compensated for by making these governorships satellites of the larger offices found in the bigger towns of the region or the capitals of regional military administrations (razriady). The larger governors' offices came to have nearly as many clerks as some Moscow chancelleries and to imitate chancellery internal organisation by distributing them among bureaux (stoly, 'desks') for specialised functions under the general direction of an experienced senior executive clerk. In the 1640s the Pskov governor's office had twenty-one clerks and by 1699 it would have fifty-four clerks, some of whom had thirty or forty years' experience.[40]

The demand for clerical manpower in the provinces after the end of the Troubles had made it necessary for Moscow to give its town governors a free hand in appointing clerks and to accept as eligible men of all kinds of backgrounds: church clerks, the sons of priests, servicemen, merchants' sons, the sons of taxpaying townsmen and state peasants and declasse itinerants. After about 1640 this was no longer affordable, for taxpayers or servicemen enrolled as clerks thereby left the tax and military service rolls. The central chancelleries therefore began tightening their control over the appointment of clerks (eventually all appointments would be controlled by the Military Chancellery). The chancelleries moved towards standardising clerical pay rates, and they gradually reduced the range of social estates and ranks eligible for clerical appointment. Cossacks and musketeers were forbidden to take service as clerks; by the i660s-i670s it was the rule that deti boiarskie could be appointed as clerks only if they had retired from military service, lacked the pomest'e lands to render military service or had not yet received formal initiation into military service. By the end of the century not even this was permitted: now no candidate could be appointed whose father had been registered in military service or on the tax rolls; only those whose fathers had been clerks were allowed to continue clerking in the governors' offices.

Thus the clericate became a closed hereditary corporation. Although this probably had the effect of slowing the growth rate of the provincial clericate, it had the advantage ofimproving clerical training and esprit de corps and making clerical service a life profession. Local clerical 'dynasties' emerged, with clerks accumulating decades of experience in the local governor's office and passing their training on to their sons, some of whom eventually worked their way up into the clericate of the central chancelleries. There was increased likelihood that clerical dynasties would tend to conduct themselves as local elites and exploit their neighbours, but clerical dynasties at least were motivated to attend closely to apprentice training out of self-interest.[41]

Local government in reconstruction and reform

The spread and systematisation of town governor administration was crucial to Patriarch Filaret's reconstruction programme (1619-33): the town governors helped reassemble and update chancellery cadastral knowledge, review the monasteries' fiscal immunities, return fugitive townsmen to the tax rolls, introduce new extraordinary taxes for military exigencies, suppress banditry and rebuild the pomest'e-based cavalry army by expediting response to petitions for entitlement award and land allotment.

In the period 1633-48 policy was made by the succession of cliques led by I. B. Cherkasskii, F. I. Sheremetev and B. I. Morozov. They gave priority to accelerating colonisation of the southern frontier and eliminating the tax-exempt social categories and enclaves in the towns. Town governor administration played an essential role in both projects.

The years 1648-54 saw town governor authority used to implement several important reforms strengthening the southern frontier defence system: the completion of most of the Belgorod Line; levies into the newly revived foreign formation infantry and cavalry regiments; the subjection of southern servicemen to the grain taxes (quarter grain, siege grain etc.) previously paid only by peasants and townsmen; and the laying of foundations for the vast Belgorod regional military administration (Belgorodskii razriad), which subordinated several town governors' offices in the south to the senior commander's office at Belgorod, not only for mobilisations and joint military operations but also for review of judicial, fiscal and land allotment matters. An equally significant reform in this period affected civil and criminal justice in governors' courts across the realm: the Ulozhenie law code (1649) greatly expanded and standardised instructions for investigations and hearings in the local courts and streamlined and further centralised judicial administration by giving the duma functions of an appellate court and by further concentrating the supervision of criminal justice matters in the Robbery Chancellery. The Ulozhenie also ended the time limit for the recovery of fugitive peasants, thereby completing the process of peasant enserfment, and provided instructions for the governors' offices to enforce enserfment by conducting mass dragnets of fugitive peasants and townsmen as well as holding hearings for fugitive remands. The fact that the zemskii sobor was no longer convened after 1653 may testify to the centre's confidence in town governor administration by this point: apparently the flow of information from governors' reports and accounts and community petitions was now considered regular and reliable enough to support decision- making in the duma and chancelleries without any need to supplement it by periodically assembling representatives of the estates to solicit their views.

During the Thirteen Years War expenditure on army pay (particularly upon the more expensive foreign formation regiments, which accounted for some 75-80 per cent) increased enormously, exceeding a million roubles annually by 1663, about four times what army service allowances had totalled in 1632.[42]The sharp rise in tax rates and infantry levy quotas in the war years was all the harder to bear because grain taxes and infantry conscription no longer fell only upon men of draft (tiaglye liudi) traditionally defined, and because ruinous inflation had resulted from the government's decision to debase coinage. The governors' offices came under great pressure to keep cash, grain and manpower resources flowing while at the same time policing against desertion, taxpayer flight and riot. To tighten central control over their accounting and policing two new chancelleries with broad investigatory powers were created: a Privy Chancellery (founded in 1654) and an Auditing Chancellery (founded in 1656). A second great regional military administration was also established at Sevsk to further co-ordinate resource mobilisation and military operations on the southern frontier.

The Andrusovo Armistice (1667) did not lead to any significant relief from high grain taxation and infantry conscription rates. It remained necessary to garrison eastern Ukraine, to keep Moscow's puppet hetmans Mnogogreshnyi and Samoilovich in power and hold Hetman Doroshenko at bay; it was also necessary to defend against the Crimean Tatars by reinforcing the Belgorod Line and sending troops down the Donto assist (and control) the Don cossacks; and in 1674 a Muscovite army had to take the field in western Ukraine to defeat Doroshenko, who was now actively supported by Ottoman forces. The defeat ofDoroshenko led immediately to the first Russo-Turkish war (1676-81), which depopulated much of eastern Ukraine and deterred the Ottomans from invading western Ukraine but also revealed the need to reform Muscovite military and fiscal practices. More regional military administrations were therefore formed (the Riazan', Tambov, Kazan', Smolensk and Vladimir razriady). A new Iziuma Line was built to extend the southern frontier defence a further 160 kilometres southward and shield military colonisation in Sloboda Ukraine. In 1678-80 six new foreign formation cavalry and ten new foreign formation infantry regiments were created, while the number of southern servicemen in the traditional formation cavalry was reduced by limiting eligibility to prosperous men holding at least twenty-four peasant households and therefore presumably able to maintain themselves in service from their pomest'ia alone, without cash allowances. To meet the higher costs for new foreign formation troop pay, a major reform of state finances was undertaken. It started with a new general cadastral survey (1677-9), the first since 1646; led to the decision (1679) to shift to the assessment of direct taxes by household, thereby abandoning the old method of assessing by sokha (i.e. by area and productive capacity of cultivated land); saw the amalgamation of a number of minor direct taxes into a single 'musketeers' money' tax for the army; and culminated in the founding of the Grand Treasury and the production of the first rudimentary state budget (1680). The simplification of direct taxation enhanced central chancellery control and permitted a further division of labour over fiscal matters at the local level, with the town governors' offices made responsible largely for recording and actual collection of taxes left to elected community representatives.

Efforts at bureaucratic rationalisation

Over the course of the seventeenth century voevoda administration came to display more of the characteristics of rational bureaucratic organisation. It was already significantly differentiated: official duties were distinguished from the pursuit of personal interests, it being an already long-established principle that the governor's office (the s"ezzhaia izba, assembly house) was separate from his residence (voevodskii dvor) and that he was forbidden to hold documents or the town seal at the latter; and there was some formal division of labour, at least within the larger offices - horizontally, in the form of discrete clerkships or even bureaux with specialised functions, and vertically, with supervising signatory clerks, document clerks and secretaries reporting in turn to the governor. By mid-century it had even become the tendency to rename the governor's office a prikaznaia izba in recognition that its organisation was increasingly resembling that of a small chancellery. Office work was subject to various integrating mechanisms promoting standardised practice: there was a comprehensive and fairly consistent repertory of routines for handling incoming business, recording expenditures and services performed and reporting up important information and unresolved business; and although there was as yet no uniform written General Regulation covering all aspects of office work, that sphere of activity where written regulations were most necessary - the administration of justice - had finally received a comprehensive code of procedures with the promulgation of the Ulozhenie. Surety bonding, oaths ofconduct, annual and end-of-term audits and investigations went some way towards tightening constraints over the conduct of governors and their staffs. To enhance co-ordination and compensate for the limited effectiveness of central control mechanisms, most executive decision-making was removed from the governors' offices and located above them in the chancelleries, with ultimate executive policy-making removed to an even higher level, above the central chancellery bureaucracy, in the duma counselling circle.