KAIROS

‘We are the ones who confront head-on,’ said the professor, once they were out of the big airport building, waiting for their taxi. He took pleasure in deep breaths of warm, gentle Greek air.

He was eighty-one years old, with a wife twenty years his junior, a woman he had married prudently, as the air was leaking out of his first marriage, his adult children having left the nest. And it was a good thing, because that other wife now needed to be cared for herself, living out her days in a perfectly reasonable retirement home.

He handled the flight well, and a few hours’ time difference didn’t really make a difference; the rhythm of the professor’s sleep had long since come to resemble a cacophonous symphony, random timetables of unexpected sleepiness and dazzling lucidity. The time change merely shifted those chaotic chords of waking and sleep by seven hours.

The air-conditioned taxi took them to their hotel; there, Karen, the professor’s younger wife, skilfully oversaw the unloading of their baggage, collected information from the organizers of the cruise at reception, got the keys and then, accepting help from a solicitous porter – for this was no easy task – took her husband up to the second floor, to their room. There she carefully arranged him in their bed, loosened his scarf and took his shoes off for him. Instantly he was asleep.

And they were in Athens! She was happy, she went up to the window and struggled for a second with its ingenious latch. Athens in April. Spring at full tilt, leaves feverishly clambering into space. The dust had risen already outside, but it wasn’t yet severe; and the noise, of course: ever-present. She shut the window.

In the bathroom Karen tousled her short grey hair and got into the shower. Inside it she felt all her tension washing away with the soap, pooling at her feet, then escaping for all eternity down the drain.

Nothing to get worked up about, she reminded herself, deep down. All of our bodies must conform to the world. There is no other way.

‘We’re nearing the finish line,’ she said aloud, standing still under the stream of warm water. And because somehow she couldn’t help but think in images – which, she thought, had almost certainly been a hindrance to her academic career – she saw something like an ancient Greek gymnasium with its characteristic starting block raised on cables, and its runners, her husband and herself, trotting awkwardly towards the finish line, although they’d only just taken off.

She wrapped a fluffy towel around herself and applied moisturizer, thoroughly, to her face, neck and chest. The familiar scent of the cream soothed her fully now, so she lay down for a moment on the made bed beside her husband, and fell asleep without realizing.

Over dinner, which they ate downstairs, in the restaurant (sole and broccoli for him, for her a feta salad), the professor asked her if they’d brought his notebooks, books, outlines, until finally among those ordinary questions there came the one that sooner or later had to arrive, revealing the latest situation on the front:

‘My dear, where are we right now?’

She reacted calmly. She explained in a few simple sentences.

‘Ah, of course,’ he said happily. ‘I’m ever so slightly discombobulated.’

She ordered herself a bottle of retsina and looked around the restaurant. Mostly wealthy tourists, Americans, Germans, Brits, and also those who had lost – in the free flow of money, which they let guide them – any and all defining traits. They were simply attractive, healthy, moving with unsummoned ease from language to language.

At the table next to theirs, for example, sat a pleasant group, people who might have been a little younger than she was, happy fifty-somethings, hale and flushed. Three men and two women in fits of laughter, the waiter bringing them another bottle of Greek wine – Karen had no doubt she would have fit in. It occurred to her that she could leave her husband, who just then was scraping apart the pale corpse of his fish with a trembling fork. She could grab her retsina and as naturally as a dandelion seed fall onto a chair at that next table, catching onto the final chords of those people’s laughter, chiming in with her own smooth alto.

Of course she did not do so. She got to gathering up the broccoli from the placemat, which had jumped ship from the professor’s plate, offended at his incompetence.

‘Gods in heaven,’ she snapped, calling over the waiter to request some herbal tea. Then, turning back to him: ‘Can I help you?’

‘I draw the line at being fed,’ he said, and with redoubled strength went back to hacking at his fish.

Often she got mad at him. The man was utterly dependent on her, and yet he acted as though it were the reverse. She thought to herself that men, or at least the cleverest among them, must be prompted by some self-preservation instinct in clinging to much younger women, not realizing it, near desperation – but not at all for the reasons sociobiologists ascribed them. Since no, it was in no way connected to reproduction, to genes, to stuffing their DNA into the tiny little tubes of matter through which time coursed. It has to do instead with the presentiment men have at every moment of their lives, a foreboding adamantly hushed and hidden – that left to their own devices, in the dull, quiet company of passing time, they would atrophy faster. As though they’d been designed for a brief spurt of intensity, a high-stakes race, a triumph and, immediately afterwards, exhaustion. That what kept them alive was excitement, a costly life strategy; energy reserves eventually ran out, and then life would be lived in overdraft.

They met at a reception in the home of a mutual friend who was just finishing up his two-year appointment at their university, fifteen years earlier. The professor brought her a glass of wine, and when he handed it to her, she noticed how his totally outmoded woollen vest was coming apart at the seams, how at the professor’s hip fluttered a long, dark thread. She had just arrived to take the place of a professor who was retiring, taking on all his students; she was just furnishing her rented home and stocking up after her divorce, which would have been more painful had they had children. Her husband, after fifteen years of marriage, had left her for another woman. Karen was over forty, already a professor, with several books to her name. She specialized in lesser-known ancient cults of the Greek islands. Religious studies was her field.

It took a few years, after that meeting, before they got married. The professor’s first wife was seriously ill, which made it more difficult for him to get divorced. But even his children were on their side.

She often reflected on how her life had turned out, and she was coming to the conclusion that the truth was simple: men needed women more than women needed men. In fact, thought Karen, women could get along perfectly fine without men altogether. They tolerated solitude well, took care of their health and cultivated friendships, lasted longer – as she tried to think of other qualities, she realized she was imagining women as a highly useful breed of dog. With a certain satisfaction she began to expand this list of canine traits: they learned quickly, they liked children, they were sociable, they kept at home. It was easy to awaken in them – particularly when they were young – that mysterious, all-encompassing instinct that only sometimes was connected with the possession of offspring. But it was something decidedly greater – an encompassing of the world; the tamping into place of trails; the unfurling, then tucking in of days and nights; the establishment of soothing rituals. Rousing this instinct with little exercises in helplessness wasn’t hard. Then they’d be blinded, the algorithm would kick in, at which point it would be possible to pitch a tent, settle down in their nests, tossing everything else out of them, and the women wouldn’t even notice that the chick was a monster, and someone else’s cast-off.

The professor had retired five years earlier, receiving awards and distinctions when he took his leave, inclusion in the registry of the most meritorious academics, a commemorative publication with articles by his students; several receptions were given in his honour. One of these was attended by a comedian well-known from TV, which, truth be known, was the thing that most cheered and revived the professor.

Then they settled down permanently in a modest but comfortable home in their university town; there he occupied himself with ‘putting his papers in order’. In the morning Karen would brew him tea and make a light breakfast. She’d go through his correspondence, responding to letters and invitations, a task that hinged primarily upon declining politely. In the mornings she tried to match his early rising, sleepily preparing herself some coffee as she made his oatmeal. She’d lay out clean clothing for him. At around noon the home help would come, so Karen had a few hours to herself, as he gave in to his daily nap. In the afternoon another mug of tea, this time herbal, and then she’d see him off on the walk he took in the early evenings on his own. Reading Ovid aloud, dinner, and the nightly preparations for bed. All this interspersed with the meting out of pills and drops. Each year, for these five peaceful years, there had only been one invitation to which she’d said yes – the luxury cruises every summer around the Greek islands, where the professor gave daily lectures to the passengers, not counting Saturdays and Sundays. It was ten lectures in all, on the topics that most fascinated the professor; there was no fixed list of subjects.

The ship was called Poseidon (its black Greek letters stood in stark relief against the white hull: ΠΟΣΕΙΔΩΝ), and it contained two decks, restaurants, a billiards room, little cafés, a massage parlour, a solarium and comfortable cabins. For several years they’d occupied the same one, with a queen-sized bed, a bathroom, a table with two armchairs and a microscopic desk. On the floor a soft coffee-coloured carpet, and Karen, as she looked at it, still held out hope that in its long fibres she might still find the earring she lost here, four years before. The cabin led directly out onto the first-class deck, and in the evenings, once the professor was already asleep, Karen liked to take advantage of this amenity and stand at the railing to smoke her one daily cigarette, gazing out at the lights in the distance they had passed. The deck, heated by the sun during the day, now, too, gave off a warmth, while a dark, cool air flowed out over the water, and it seemed to Karen that her body marked the boundary between day and night.

‘For you are the saviour of ships, the tamer of war-steeds, blessed art thou, O Poseidon, wielding the earth, raven-haired and fortunate, show mercy upon the sailors,’ she’d say under her breath, and then she’d throw her barely started cigarette to the god, her daily allocation – an act of pure extravagance.

The ship’s trajectory hadn’t changed in five years.

From Piraeus it went to Eleusis, then to Corinth, and from there back south, to the island of Poros, so that the passengers could see the ruins of Poseidon’s temple and meander around the little town. Then their route took them to the Cyclades – it was all supposed to be unhurried, even lazy, so that everyone could bask in sun and sea, in the views of the towns arrayed along the islands, towns with white walls and orange roofs, scented by lemon groves. High season hadn’t started yet, so there wouldn’t be hordes of tourists – these the professor was always disparaging, unable to conceal his impatience. He felt that they looked without seeing, their gazes sliding over everything, alighting only on whatever their mass-produced guidebooks pointed out to them specifically – the print equivalent of a McDonald’s. Next they stopped on Delos, where they would study the temple of Apollo, and then finally they’d head for the Dodecanese island of Rhodes, completing their excursion there and flying home from the local airport.

Karen was fond of the afternoons when they docked at little ports, and, dressed for walking – the professor with the scarf he simply had to have around his neck – they’d go into the town. Bigger boats would also moor at these ports, and when they did the local merchants would immediately open up their little shops to offer visitors towels with the name of the island, sets of shells, sponges, mixes of dried herbs in tasteful baskets, ouzo or just ice cream.

The professor walked valiantly, indicating landmarks with his cane – gates, fountains, ruins encircled by frail barriers, and he’d tell stories his listeners would never be able to find even in the best guidebooks. These walks were not included in his contract, though. It stated just a single lecture every day.

He would begin: ‘I’m of the belief that human beings need, to live their lives, more or less the same climactic conditions as lemons.’

He’d raise his gaze to the ceiling dotted with little round lights and let it stay there for a moment longer than was strictly permissible.

Karen would clench her hands until her knuckles went white, but she thought she managed to contain the intrigued, lightly provocative smile – raised eyebrows, irony across her face.

‘This is our point of departure,’ continued her husband. ‘It is not by chance that the range of Greek civilization coincides, roughly speaking, with the incidence of citrus. Beyond this sun-drenched, life-giving realm, everything undergoes a slow, but inevitable, decline.’

It was like an unrushed, protracted take-off. Karen saw the same picture each time: the professor’s plane would stagger, its wheels dipping down into a rut, maybe even running off the runway – so he would take off from the grass. But in the end the engine would kick in, tossing from side to side, rocking, and by then it would be clear the plane would fly. And Karen would let out a discreet, relieved sigh.

She knew the topics of the lectures, knew their outlines from the index cards covered over in the professor’s miniscule handwriting, and from his notes that she would use to help him if something were indeed to happen – she could stand up from her seat in the first row and latch onto any of his sentences halfway through and just proceed, along the path he’d beaten. But it was true she wouldn’t speak with the same eloquence, nor would she permit herself the little quirks with which he held his audience’s attention, without even always being aware of them. Karen would await the moment when the professor would stand up and start pacing, which meant – returning to her picture – that his plane had reached its cruising altitude, that everything was fine, that she could now simply walk out onto the upper deck and extend her gaze in joy over the surface of the water, letting it linger on the masts of the yachts they had passed, on the just-traced mountain peaks in the light white mist.

She looked at the listeners – they were sitting in a semi-circle; those in the first row had notebooks before them on their small folded-out tables, eagerly jotting down the professor’s words. Those in the last rows, around the windows, lounging, ostentatiously indifferent, were also listening. Karen knew it was these rows that produced the most inquisitive among them, the ones who would later exhaust the professor with questions, calling her into the service of shielding her husband from all additional – now unpaid – consultations.

She was amazed by this man, her own husband. It seemed to her that he knew everything there was to know about Greece, everything that had been written, excavated, ever said. His knowledge wasn’t so much enormous as monstrous; it was made up of texts, quotes, references, citations, painstakingly deciphered words on chipped vases, drawings not entirely intelligible, dig sites, paraphrases in later writings, ashes, correspondences and concordances. There was something inhuman in all this – to be able to fit all that knowledge in himself, the professor must have needed to perform some special biological procedure, permitting it to grow into his tissues, opening his body to it and becoming a hybrid. Otherwise, it would have been impossible.

It was clear that such an enormous stock of knowledge could not be put in order; it had instead the form of a sponge, of deep-sea corals growing over years until they started to create the most fantastic forms. This was knowledge that had already attained critical mass and had since crossed over into some other state – it appeared to reproduce, to multiply, to organize in complex and binary forms. Associations travelled down unusual routes, likenesses were found in the least expected versions – like kinship in Brazilian soap operas, where anyone could turn out to be the child or husband or sister of anybody else. Well-trodden paths turned out to be worth nothing, while those thought untraversable proved convenient routes. Something that meant nothing for years suddenly – in the professor’s mind – became the departure point for some great revelation, a real paradigm shift. She had an unshakeable awareness of being the wife of a great man.

As he was speaking, his face changed, as though his words washed it clean of old age and exhaustion. A different face emerged: now his eyes shone, his cheeks lifted and tightened. The unpleasant impression of a mask that face had made only moments earlier now faded. It was as much of a change as if he had been given drugs, a small dose of amphetamines. She knew that when that drug wore off – whatever kind of drug it was – his face would freeze back, his eyes go matte, his body would slump into the nearest armchair, taking back on that appearance of helplessness she knew so well. And she would need to lift that body carefully, by its armpits, prod it ever so slightly, lead it dragging its feet and swaying to a nap in their cabin – it would have expended too much energy.

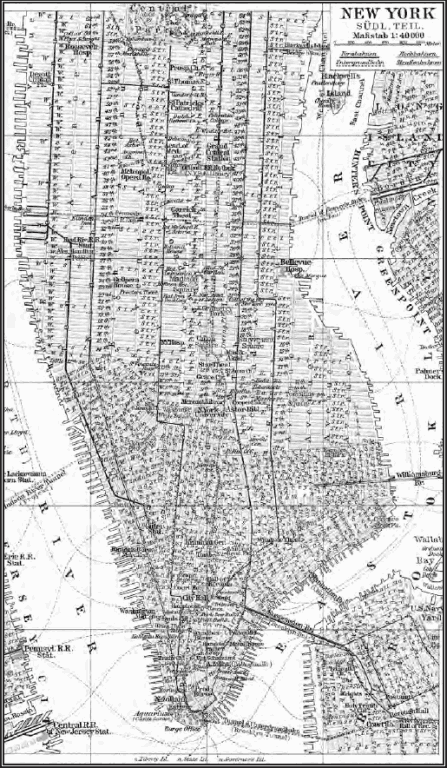

She knew the course of the lectures well. But each time it brought her pleasure to observe him, like putting a desert rose in water, as though he were recounting his own history rather than that of Greece. All the figures he mentioned were him, that was obvious. All the political problems were his problems, personal as possible. Philosophical concepts – those were what kept him up at night; they belonged to him. The gods he knew intimately, of course; he had lunch with them daily, at a restaurant near their house. Lots of nights they’d stayed up talking, drinking an Aegean Sea of wine. He knew their addresses and phone numbers, could call them up at any time. Athens he knew like the inside of his pocket, though not (needless to say) the city they’d just set sail from – that one, truth be told, did not interest him in the slightest – but rather the old Athens, from the times of, let’s say, Pericles, and their map was overlaid onto today’s layout, rendering the present one spectral, unreal.

Karen had already done her private survey of her fellow passengers that morning, when they had boarded the ship in Piraeus. Everyone, even the French, spoke English. Taxis had brought them straight from the airport in Athens or from their hotels. They were polite, attractive, intelligent. Here was a couple, in their fifties, slim, probably older than they looked, in fact, in light-coloured natural clothing, linen and cotton, him playing with his pen, her sitting up straight and loose, like someone trained in relaxation techniques. Continuing on, a young woman whose eyes were glazed by her contact lenses, taking notes, left-handed, writing in big round letters, drawing figures of eight in the margins. Behind her two gay guys, well-dressed, well-groomed, one of them wearing funny glasses à la Elton John. By the window a father with his daughter, which they mentioned immediately upon introducing themselves, the man probably afraid of being suspected of an affair with a minor; the girl always wore black and had her head shaved almost bald, with pretty dark pouting lips that betrayed an expression of irrepressibly swollen disdain. The next couple, harmoniously grey-haired, was Swedish, apparently ichthyologists – Karen had noticed this on the list of lecture participants they had received ahead of time. The Swedes were calm and looked a lot like one another, though not in the way people look like each other from birth – it was instead the kind of resemblance that must be worked at, hard, over the course of many years of marriage. A few younger people, this cruise was their first; they seemed to still be unsure whether this ancient Greek stuff was for them, or whether they wouldn’t rather delve into the mysteries of orchids or of turn-of-the-century Middle Eastern decorative arts. Was their rightful place this ship with this old man who commenced lectures by rambling about citrus fruits? Karen took a longer look at the red-headed, fair-skinned man in jeans that hung around his hips, who rubbed the several days’ worth of light-blond stubble on his face. She thought he looked German. A handsome German. And a dozen or so others, in focused silence, watching the professor.

Here was a new type of mind, thought Karen, that didn’t trust words from books, from the best textbooks, from papers, monographs, encyclopaedias – abused over the course of its studies, now it had cerebral hiccups. It had been corrupted by the ease of breaking down any construct – even the most complex – into prime factors. Reducing ad absurdum every ill-considered argumentation, taking on every few years a completely new, fashionable language, which – like the latest advertised version of a pocketknife – could do anything with everything: open cans, clean fish, interpret novels and foresee the evolution of the political situation in central Africa. A mind for charades, a mind that employed citations and cross-references like knife and fork. A rational and discursive mind, lonely and sterile. A mind that seemed to be aware of everything, even things it didn’t really understand, but that moved fast – a quick, intelligent electric impulse without limits, linking everything with everything, convinced that all of it together must mean something, even if we couldn’t yet know what.

Now, with verve, the professor began to expound upon the origins of the name Poseidon, and Karen turned her face towards the sea.

After every lecture he needed her assurance that it had gone well. In their cabin, as they dressed for dinner, she would hug him to her, his hair smelling slightly of his chamomile shampoo. Now they were ready to go, him in his lightweight dark-coloured jacket and his favourite old-fashioned scarf, her in her green velvet dress, and stood inside their cramped cabin with their faces at the windows. She handed him his little cup of wine, he took a sip and whispered a few words, then dipped his fingers in and sprinkled wine around the cabin, but carefully, so as not to stain the fluffy brownish carpet. The drops sank into the dark upholstery of the chair, wine vanishing into furniture; there would be no trace of it. She did the same.

At dinner, the golden German man joined their table, which they were sharing with the captain, and Karen saw that her husband was none too pleased with this new presence. The man, however, was pleasant, tactful. He introduced himself as a programmer, and said he worked with computers in Bergen, near the Arctic Circle. So he was Norwegian. In the soft lamplight his skin, eyes and the thin wire frames of his glasses all seemed made of gold. His white linen shirt unnecessarily covering his golden torso.

He was interested in one of the words the professor had used during his lecture, which had in fact been explained with great precision.

‘Contuition,’ repeated the professor, his irritation painstakingly concealed, ‘is, as I said, a variety of insight that spontaneously reveals the presence of some larger-than-human strength, some unity above heterogeneity. I’ll expand tomorrow,’ he added, with his mouth full.

‘Right,’ responded the man somewhat helplessly. ‘But what would that mean?’

He did not receive a response, because after ruminating for a moment, evidently searching through the stocks of the abyss of his memory, the professor finally began to trace a series of small circles in the air with his hand, reciting:

‘Reject everything, do not look, shut your eyes and change your gaze, awaken another one that almost everyone has, but that few use.’

He was so proud of himself he actually blushed.

‘Plato.’

The captain nodded knowingly, and then raised a toast – this was their fifth shared journey:

‘To our happy little anniversary.’

It was strange, but just then Karen felt certain this would be their last shared journey.

‘May we meet again next year,’ she said.

The professor, animated now, told the captain and the ginger-haired man, who introduced himself as Ole, about his latest idea.

‘A trip that would follow in the footsteps of Odysseus,’ he said, and then waited, to give them time to be astonished by the thought. ‘Approximately, of course. We’d need to think how to organize it, logistically.’ He looked at Karen, who muttered:

‘It did take Odysseus twenty years.’

‘That doesn’t matter,’ the professor replied merrily. ‘In today’s day and age you could do it in two weeks.’

Then Karen’s and Ole’s eyes met, by accident.

It was on that night or the following one that she had an orgasm, just like that, in her sleep. It was somehow connected with the red-headed Norwegian, but it wasn’t clear how, because she didn’t remember very much of what had gone on there, in her dream. She’d simply known that golden man, profoundly. She woke up with echoes of contractions in her lower abdomen, stunned, amazed and then embarrassed. Without realizing she was doing it, she started counting them, catching the final four.

The next day, as they were moving along the coast, Karen openly admitted to herself that in many places, at this stage, there was nothing left to see.

The road to Eleusis was an asphalt highway down which cars went speeding; thirty kilometres of ugliness and banality, desiccated hard shoulders, concrete homes, ads, parking lots and land it wouldn’t have made sense to cultivate. Warehouses, loading ramps, a giant dirty port, a heating plant.

Once they were ashore, the professor led the whole group to the ruins of Demeter’s temple, which now looked rather sad. The group could not conceal its disappointment, so he called on all of them to imagine turning back time.

‘This route from Athens was barely reinforced by stones back then, and very narrow – look, swarms of people move along it towards Eleusis, walking, kicking up the dust feared by the greatest rulers of the world. The packed crowd cries out, the sound of hundreds of throats.’

The professor stood still, leaned back on his heels, wedging his cane into the ground, and said:

‘It might have sounded something like this,’ and his voice cut off for a moment, for him to gather his breath, and then he shouted out with all the strength of his old throat. And suddenly his voice loud and clear. His wailing was carried by the heated air, causing everyone to look up: surprised tourists on their own, making their way between the rocks, and ice cream vendors, and workers lining the railings because high season was about to start now, and a small child poking at a frightened beetle with a stick, and two donkeys grazing off in the distance, on the other side of the slope.

‘Iacchus, Iacchus,’ cried the professor with his eyes closed.

Even after he had fallen silent again, his shout still hung in the air, so that everything held its breath for half a minute, for a few dozen strange seconds. Jarred by this eccentric comportment, his listeners couldn’t bring themselves to even look at one another, and Karen turned bright red, as though it had been her crying out in that strange way. She moved off to the side, to cool off from her embarrassment and from the heat.

But the old man didn’t look even remotely chagrined.

‘…and perhaps it is possible,’ she heard him say, ‘to look into the past, cast our glances backwards, imagine it as a panopticon of sorts, or, dear friends, to treat the past as though it still existed, it’s just that it’s been shifted over into another dimension. Maybe all we need to do is change our way of looking, look askance at it all somehow. Because if the future and the past are infinite, then in reality there can be no ‘once upon’, no ‘back when’. Different moments in time hang in space like sheets, like screens lit up by one moment; the world is made up of these frozen moments, great meta-images, and we just hop from one to the next.’

He broke off for a moment to rest, because they were walking uphill, and then Karen heard him squeeze the next words out between his whistling breaths:

‘In reality, movement doesn’t exist. Like the turtle in Zeno’s paradox, we’re heading nowhere, if anything we’re simply wandering into the interior of a moment, and there is no end, nor any destination. And the same might apply to space – since we are all identically removed from infinity, there can also be no somewhere – nothing is truly anchored on any day, nor in any place.’

That evening Karen did a mental breakdown of the costs of that expedition: a burned nose and forehead, a foot injured to bleeding. A sharp stone had got under the strap of his sandal, and he hadn’t felt it. That must have been a serious symptom of worsening arteriosclerosis, which the professor had had for many years.

She knew this body well, too well – shrunken, sunken, the dried-out skin dappled with brown spots. The remains of grey hairs on his chest, his frail neck that barely held up his trembling head, the thin bones beneath a thin covering of skin and a skeleton that seemed made of aluminium it was so light, avian.

Sometimes he fell asleep before she had managed to undress him and prepare the bed, and then she had to carefully remove his jacket and shoes and steer him, still slumbering, towards the bed.

Every morning they had the same problem – his shoes. The professor suffered from an irritating ailment – he had ingrowing nails. His toes became inflamed, swollen, his nails got raised, boring holes into his socks, scraping painfully against the tops of his shoes. Placing a foot in such pain in its black leather slipper would be a gratuitous act of cruelty. So, for everyday things the professor wore sandals, and covered shoes they ordered from a particular shoemaker near where they lived, and for an incredible sum he would produce for the professor beautiful soft shoes, with a raised top, loose.

That evening, likely from the sun, he had a fever, so Karen gave up on dinner at the table and ordered food to their cabin.

In the morning, as the ship was sailing up to Delos, after brushing their teeth and a laborious shave, they went out together onto the deck with the pastries from the previous day’s tea. They crumbled them and threw them into the sea. It was early, everyone else was probably asleep. But the sun had already lost its redness and was shining, gathering its strength moment by moment. The water had turned a golden, honey colour, thick, the waves had died down, and the great iron of the sun pressed them without leaving even the finest line. The professor put his arm around Karen’s shoulder, and in fact that was the only gesture to be made in the face of such an obvious epiphany.

Looking around where you are once more is like looking at an image in which a million details conceal a hidden shape. Once you see it, you can never forget it’s there.

I won’t record every day of the trip, nor relay each lecture – in any case, Karen might have them published someday. The ship sailed, every evening there was dancing on the deck, the passengers with glasses of wine in their hands, leaning against the railings, having lazy conversations. Others gazed out at the night-time sea, at the cool, crystal darkness, lit up from time to time by the lights of big ships, bearing thousands of passengers, calling daily at different ports.

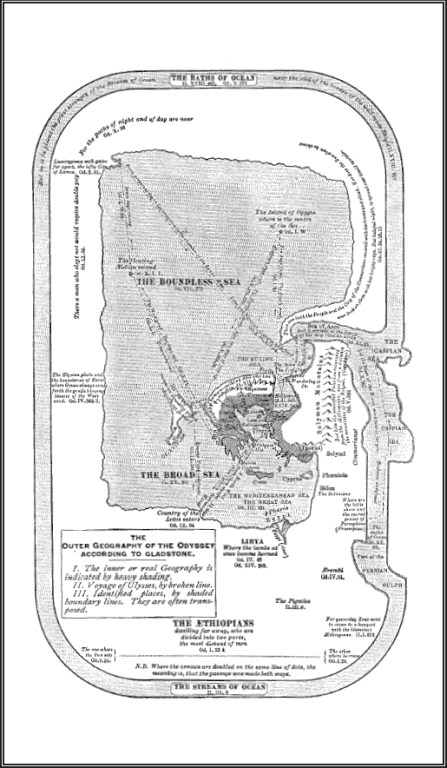

I’ll mention only one lecture, which happened also to be my favourite. Karen had come up with the idea, to talk about those gods who didn’t make it into the pages of the famous, popular books, those not mentioned by Homer, then ignored by Ovid; those who didn’t make names for themselves with drama or romance; who weren’t terrifying enough, cunning enough, elusive enough, who are known only from fragments of rock, from mentions, from the little extant from burned-down libraries. But thanks to that they’ve preserved something the well-known gods have lost forever – a divine volatility and ungraspability, a fluidity of form, an uncertainty of genealogy. They emerge from the shadows, from formlessness, then succumb once more to looming darkness. Just take Kairos, who always operates at the intersection of linear, human time and divine time – circular time. And at the intersection between place and time, at that moment that opens up for just a little while, to situate that single, right, unrepeatable possibility. The point where the straight line that runs from nowhere to nowhere makes – for one moment – contact with the circle.

He entered the room with a brisk step, dragging his feet and panting, and stood at his podium – the ordinary little restaurant table – and took a bundle out from under his arm. She knew his methods. The bundle was a towel, right out of their cabin. He knew perfectly well that as soon as he began to unroll it the room would fall silent, and the heads in the last row would incline towards him. People are children. Under the towel there was, first, her red scarf, and then, finally, there shone something white, a piece of marble, which may have looked like some shard of rock. The tension in the room had reached its pinnacle, and he, aware of the interest he was arousing, celebrated it with a slight sly smile, drawing out his gestures like he was acting in a movie. Then he lifted that light, flat piece almost to eye level, extending his arm, parodying Hamlet, and began:

Who is the sculptor, and where does he come from?

From Sicyon.

And his name?

Lysippus.

And who are you?

Kairos the All-Mastering.

Why do you tread on tiptoes?

I ceaselessly circumnavigate the world.

Why do you have wings on both feet?

Because I fly by with the wind.

And in your right hand, why do you carry a razor?

It is a sign to people that I am sharper than any blade.

Why does your hair fall over your eyes?

So that anyone who confronts me head-on can still catch me.

But, by Zeus, why is the back of your head bald?

So that no one I’ve run over with my winged feet,

Might seize me from behind, for much as he desired to do so.

Why did the sculptor create you?

On account of you, foreigners, and he set me at the entrance as a lesson.

He began with this lovely epigram by Posidippus – he ought to have used it as an epitaph. The professor went up to the first seats and handed the proof of the god’s existence over to his audience. The girl with the swollen, contemptuous lips reached out for the relief with exaggerated caution, sticking out her tongue slightly from the exertion. She passed it on, while the professor waited in silence, until the small god had made it halfway around the room, and then, with a stony expression on his face, he said:

‘Please don’t worry, it’s a plaster cast from a museum gift shop. Fifteen euros.’

Karen heard a murmur of laughter, the shifting of the listeners’ bodies, the scraping of someone’s chair – a clear sign that the tension had been broken. He’d started well. He must be having a good day today.

She quietly slipped out onto the deck and lit a cigarette, looking at the island of Rhodes as it got nearer, and the big ferries, the beaches still mostly empty at this time of year, and the city, which like some colony of insects climbed up the steep slope towards the bright sun. She stood there, enveloped in a peace that suddenly flowered over her, who knew from where.

She saw the island’s shores, and its caves. Cloisters and the naves carved into the rock by the water brought strange temples to her mind. Something had carefully built them over millions of years, that same force that now bore their small ship, rocked them. A thick transparent power, that had its workshops on land, as well.

Here were the prototypes of cathedrals, the slender towers and the catacombs, thought Karen. Those evenly stacked layers of rock on the shore, perfectly rounded stones, carefully elaborated over the ages, and grains of sand, and the ovals of caves. The veins of granite in sandstone, their asymmetrical, intriguing pattern, the regular line of the island’s shore, the shades of sand on the beaches. Monumental buildings and fine jewellery. What, in the face of this, could those little strings of houses lining the shores ever hope to be? Those little ports, those little ships, those little human shops, where with excessive confidence old ideas – simplified and in miniature – were sold.

Now she recalled the water grotto they’d seen somewhere on the Adriatic. Poseidon’s Grotto, where once a day the sun burst through an opening in the top. She remembered she herself had been next to the column of light as it pierced – sharp as a needle – the green water, and for just an instant revealed the sandy bed below. It lasted just a moment before the sun continued on its way.

The cigarette disappeared with a hiss into the great mouth of the sea.

He was sleeping on his side, with a hand under his cheek, his lips parted. His trouser leg had rolled up and now showed his grey cotton sock. She lay down beside him gently, put her arm around his waist and kissed his back in its woollen vest. It occurred to her that after he was gone she’d have to stay a little longer, even just to tidy all their things up and make room for others. She’d gather all his notes, go through them, probably publish them. She’d arrange things with the publishers – several of his books had already been made into textbooks. And in reality there was no reason not to continue his lectures, although she wasn’t sure the university would invite her to do so. But she would definitely want to take over these mobile Poseidon-like seminars on this meandering ship (if they asked her). Then she’d be able to add a lot of her own things. She thought about how no one had taught us to grow old, how we didn’t know what it would be like. When we were young we thought of old age as an ailment that affected only other people. While we, for reasons never entirely clear, would remain young. We treated the old as though they were responsible for their condition somehow, as though they’d done something to earn it, like some types of diabetes or arteriosclerosis. And yet this was an ailment that affected the absolute most innocent. And, her eyes closed now, she thought of something else: the fact that her back remained uncovered. Who would hold her?

In the morning the sea was so calm, the weather so pretty, that everyone went out onto the deck. Someone was insisting that with such great weather they ought to be able to see in the distance the Turkish coast of Mount Ararat. But all they saw was a high rocky shore. From the sea the massif looked so powerful, dappled with bright splotches of bare rock resembling bones. The professor stood hunched over with his neck wrapped up in her red scarf, squinting. An image came to Karen’s mind: they were sailing underwater, because in reality the water level was high, like in times of flood; they were moving in an illuminated greenish space that slowed their motion and drowned out their words. Her scarf no longer flapped obnoxiously, but rippled, silent, and her husband’s dark eyes looked at her so softly, gently, rinsed by omnipresent salty tears. Glistening even more was Ole’s red-gold hair, his whole body like a drop of resin in the water that would harden into amber soon. And high above their heads someone’s hands were just releasing a bird to scout out the mainland, and soon they’d realize it was known where we were sailing, and just then that same hand was pointing out a mountaintop, a safe spot for a new beginning.

In that same moment she heard screams from up ahead, and instantly a hysterical whistle of warning, and the captain, who’d just been standing nearby, now ran towards the bridge, which, since it was such a violent departure from his usual decorum, frightened Karen. The passengers all started screaming and waving their hands; those leaning against the railings were no longer aiming their wide eyes at the mythical Ararat, but at something down below. Karen felt the ship brake sharply, the deck shifting and shuddering beneath their feet, and at the last possible moment she seized the metal of the railing and quickly tried to catch her husband’s hand, but she saw the professor pawing his way backwards, taking tiny steps, like she was watching a movie playing in reverse. On his face amusement arising from surprise, but not fear. His eyes said something like: ‘Catch me.’ Then she saw him hit his back and head on the iron scaffolding of the stairs, saw him bounce off of them and fall onto his knees. In the same instant from up ahead she heard the bang of a collision and people’s shouting, and then the splash of life buoys and the powerful impact in the water of a life boat, because – as Karen was able to put together from other people’s shouts – they’d rammed into some little yacht.

Around her people were rising from the deck, nobody else injured, and she was kneeling down beside her husband gently trying to revive him. He was blinking, blinks that were too long, and then he said quite audibly: ‘Pick me up!’ But that couldn’t be done now, his body refused to obey, so Karen lay his head on her lap and waited for help to arrive.

The professor’s well-selected health insurance meant that that same day he got transferred by helicopter from Rhodes to the hospital in Athens, where he underwent a battery of tests. The CT scan revealed extensive damage to the left hemisphere of his brain; he’d had a massive stroke. There was no way to stop it. Karen sat by his side to the end, stroking his already limp hand. The right side of his body was completely stiff; his eye stayed shut. Karen had called his children, who must have been en route by now. She sat up next to him all night, whispering into his ear, believing he heard and understood her. She led him down the dusty road among the ads, the warehouses, the ramps, the dirty garages, down the side of the highway, all night.

But the crimson inner ocean of the professor’s head rose from the swells of blood-bearing rivers and gradually flooded realm after realm – first the plains of Europe, where he’d been born and raised. Cities disappeared underwater, and the bridges and dams built so methodically by generations of his ancestors. The ocean reached the threshold of their reed-roofed home and boldly stepped inside. It unfurled a red carpet over those stone floors, the floorboards of the kitchen, scrubbed each Saturday, finally putting out the fire in the fireplace, attaining the cupboards and tables. Then it poured into the railway stations and the airports that had sent the professor off into the world. The towns he’d travelled to drowned in it, and in them the streets where he had stayed a while in rented rooms, the cheap hotels he’d lived in, the restaurants where he’d dined. The shimmering red surface of the water now reached the lowest shelves of his favourite libraries, the books’ pages bulging, including those in which his name was on the title page. Its red tongue licked the letters, and the black print melted clean away. The floors were soaked in red, the stairs he’d walked up and down to collect his children’s school certificates, the walkway he’d gone down during the ceremony to receive his professorship. Red stains were already collecting on the sheets where he and Karen had first fallen and undone the drawstrings of their older, clumsy bodies. The viscous liquid permanently glued together the compartments of his wallet where he kept his credit cards and plane tickets and the photos of his grandkids. The stream flooded train stations, tracks, airports and runways – never would another airplane take off from them, never would another train depart for any destination.

The sea level was rising relentlessly, the waters swept up words, ideas and memories; the streetlights went out under them, lamp bulbs bursting; cables shorted, the whole network of connections transformed into dead spiderweb, a lame and useless game of telephone. Screens were extinguished. And finally that slow, infinite ocean began to come up to the hospital, and Athens itself stood in blood – the temples, the sacred roads and groves, the agora empty at this hour, the bright statue of the goddess and her little olive tree.

She was by his side when they made the decision to unplug the machine that wasn’t necessary now, and when the gentle hands of the Greek nurse covered in one deft motion his face with the sheet.

The body was cremated, and Karen and his children scattered the ashes into the Aegean sea, believing this to be the funeral he would have wanted.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ