These austerities frightened potential novices; the little band grew slowly, and the new order might have died in infancy had not fresh ardor come to it in the person of St. Bernard. Born near Dijon (1091) of a knightly family, he became a shy and pious youth, loving solitude. Finding the secular world an uncomfortable place, he determined to enter a monastery. But, as if desiring companionship in solitude, he made effective propaganda among his relatives and friends to enter Cîteaux with him; mothers and nubile girls, we are told, trembled at his approach, fearing that he would lure their sons or lovers into chastity. Despite their tears and charms he succeeded; and when he was admitted to Cîteaux (1113) he brought with him a band of twenty-nine candidates, including brothers, an uncle, and friends. Later he persuaded his mother and sister to become nuns, and his father a monk, on the promise that “unless thou do penance thou shalt burn forever … and send forth smoke and stench.”22

Stephen Harding came presently to such admiration for Bernard’s piety and energy that he sent him forth (1115) as abbot, with twelve other monks, to found a new Cistercian house. Bernard chose a heavily wooded spot, ninety miles from Cîteaux, known as Clara vallis, Bright Valley, Clairvaux. There was no habitation there, and no human life. The initial task of the fraternal band was to build with their own hands their first “monastery”—a wooden building containing under one roof a chapel, a refectory, and a dormitory loft reached by a ladder; the beds were bins strewn with leaves; the windows were no larger than a man’s head; the floor was the earth. Diet was vegetarian except for an occasional fish; no white bread, no spices, little wine; these monks eager for heaven ate like philosophers courting longevity. The monks prepared their own meals, each serving as cook in turn. By the rule that Bernard drew up, the monastery could not buy property; it could own only what was given it; he hoped that it would never have more land than could be worked by the monks’ own hands and simple tools. In that quiet valley Bernard and his growing fellowship labored in silence and content, free from the “storm of the world,” clearing the forest, planting and reaping, making their own furniture, and coming together at the canonical hours to sing, without an organ, the psalms and hymns of the day. “The more attentively I watch them,” said William of St. Thierry, “the more I believe that they are perfect followers of Christ… a little less than angels, but much more than men.”23 The news of this Christian peace and self-containment spread, and before Bernard’s death there were 700 monks at Clairvaux. They must have been happy there, for nearly all who were sent from that communistic enclave to serve as abbots, bishops, and councilors longed to return; and Bernard himself, offered the highest dignities in the Church, and going to many lands at her bidding, always yearned to get back to his cell at Clairvaux, “that my eyes may be closed by the hands of my children, and that my body may be laid at Clairvaux side by side with the bodies of the poor.”24

He was a man of moderate intellect, of strong conviction, of immense force and unity of character. He cared nothing for science or philosophy. The mind of man, he felt, was too infinitesimal a portion of the universe to sit in judgment upon it or pretend to understand it. He marveled at the silly pride of philosophers prating about the nature, origin, and destiny of the cosmos. He was shocked by Abélard’s proposal to submit faith to reason, and he fought that rationalism as a blasphemous impudence. Instead of trying to understand the universe he preferred to walk unquestioning and grateful in the miracle of revelation. He accepted the Bible as God’s word, for otherwise, it seemed to him, life would be a desert of dark uncertainty. The more he preached that childlike faith the more surely he felt it to be the Way. When one of his monks, in terror, confessed to him that he could not believe in the power of the priest to change the bread of the Eucharist into the body and blood of Christ, Bernard did not reprove him; he bade him receive the sacrament nevertheless; “go and communicate with my faith”; and we are assured that Bernard’s faith overflowed into the doubter and saved his soul.25 Bernard could hate and pursue, almost to the death, heretics like Abélard or Arnold of Brescia, who weakened a Church which, with all her faults, seemed to him the very vehicle of Christ; and he could love with almost the tenderness of the Virgin whom he worshiped so fervently. Seeing a thief on the way to the gallows, he begged the count of Champagne for him, promising that he would subject the man to a harder penance than a moment’s death.26 He preached to kings and popes, but more contentedly to the peasants and shepherds of his valley; he was lenient with their faults, converted them by his example, and earned their mute love for the faith and love he gave them. He carried his piety to an exhausting asceticism; he fasted so much that his superior at Cîteaux had to command him to eat; and for thirty-eight years he lived in one cramped cell at Clairvaux, with a bed of straw and no seat but a cut in the wall.27 All the comforts and goods of the world seemed to him as nothing compared with the thought and promise of Christ. He wrote in this mood several hymns of unassuming simplicity and touching tenderness:

Iesu dulcis memoria,

dans vera cordi gaudia,

sed super mel et omnia

eius dulcis praesentia.

Nil canitur suavius,

auditur nil iocundius,

nil cogitatur dulcius

quam Iesu Dei filius.

Iesu spes poenitentibus,

quam pius es petentibus,

quam bonus es quaerentibus,

sed quid invenientibus?28

Jesus sweet in memory,

Giving the heart true joy,

Yea, beyond honey and all things,

Sweet is His presence.

Nothing sung is lovelier,

Nothing heard is pleasanter,

Nothing thought is sweeter

Than Jesus the Son of God.

Jesus hope of the penitent,

How gentle Thou art to suppliants!

How good to those seeking Thee!

What must Thou be to those finding Thee?

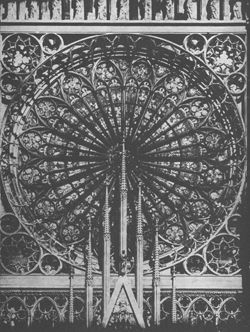

Despite his flair for graceful speech he cared little for any but spiritual beauty. He covered his eyes lest they take too sensual a delight from the lakes of Switzerland.29 His abbey was bare of all ornament except the crucified Christ. He berated Cluny for spending so much on the architecture and adornment of its abbeys. “The church,” he said, “is resplendent in its walls and wholly lacking in its poor. It gilds its stones and leaves its children naked. With the silver of the wretched it charms the eyes of the rich.”30 He complained that the great abbey of St. Denis was crowded with proud and armored knights instead of simple worshipers; he called it “a garrison, a school of Satan, a den of thieves.”31 Suger, humbly moved by these strictures, reformed the customs of his church and his monks, and lived to earn Bernard’s praise.

The monastic reform that radiated from Clairvaux, and the improvement of the hierarchy through the elevation of Bernard’s monks to bishoprics and archbishoprics, were but a part of the influence which this astonishing man, who asked nothing but bread, wielded on all ranks in his half century. Henry of France, brother of the king, came to visit him; Bernard spoke to him; on that day Henry became a monk, and washed the dishes at Clairvaux.32 Through his sermons—themselves so eloquent and sensuous as to verge on poetry—he moved all who heard him; through his letters—masterpieces of passionate pleading—he influenced councils, bishops, popes, kings; through personal contacts he molded the policies of Church and state. He refused to be more than an abbot, but he made and unmade popes, and no pontiff was heard with greater respect or reverence. He left his cell on a dozen errands of high diplomacy, usually at the call of the Church. When contending groups chose Anacletus II and Innocent II as rival popes (1130), Bernard supported Innocent; when Anacletus captured Rome Bernard entered Italy, and by the pure power of his personality and his speech roused the Lombard cities for Innocent; the crowds, drunk with his oratory and his sanctity, kissed his feet and tore his garments to pieces as sacred relics for their posterity. The sick came to him at Milan, and epileptics, paralytics, and other ailing faithful announced that they had been cured by his touch. On his return to Clairvaux from his diplomatic triumphs the peasants would come in from the fields, and the shepherds down from the hills, to ask his blessing; and receiving it they would return to their toil uplifted and content.

When Bernard died in 1153 the number of Cistercian houses had risen from 30 in 1134 (the year of Stephen Harding’s death) to 343. The fame of his sanctity and his power brought many converts to the new order; by 1300 it had 60,000 monks in 693 monasteries. Other monastic orders took form in the twelfth century. About 1100 Robert of Arbrissol founded the order of Fontevrault in Anjou; in 1120 St. Norbert gave up a rich inheritance to establish the Premonstratensian order of Canons Regular at Prémontré near Laon; in 1131 St. Gilbert constituted the English order of Sempringham—the Gilbertines—on the model of Fontevrault. About 1150 some Palestinian anchorites adopted the eremitical rule of St. Basil, and spread throughout Palestine; when the Moslems captured the Holy Land these “Carmelites” migrated to Cyprus, Sicily, France, and England. In 1198 Innocent III approved the articles of the order of Trinitarians, and dedicated it to the ransoming of Christians captured by Saracens. These new orders were a saving and uplifting leaven in the Christian Church.

The burst of monastic reform climaxed by Bernard died down as the twelfth century advanced. The younger orders kept their arduous rules with reasonable fidelity; but not many men could be found, in that dynamic period, to bear so strict a regimen. In time the Cistercians—even at Bernard’s Clairvaux—became rich through hopeful gifts; endowments for “pittances” enabled the monks to add meat to their diet, and plenty of wine;33 they delegated all manual labor to lay brothers; four years after Bernard’s death they bought a supply of Saracen slaves;34 they developed a large and profitable trade in the products of their socialistic industry, and aroused guild animosity through their exemption from transportation tolls.35 The decline of faith as the Crusades failed reduced the number of novices, and disturbed the morale of all the monastic orders. But the old ideal of living like the apostles in a propertyless communism did not die; the conviction that the true Christian must shun wealth and power, and be a man of unflinching peace, lingered in thousands of souls. At the opening of the thirteenth century a man appeared, in the Umbrian hills of Italy, who brought these old ideals to vigor again by such a life of simplicity, purity, piety, and love that men wondered had Christ been born again.

III. ST. FRANCIS*

Giovanni de Bernadone was born in 1182 in Assisi, son of Ser Pietro de Bernadone, a wealthy merchant who did much business with Provence. There Pietro had fallen in love with a French girl, Pica, and he had brought her back to Assisi as his wife. When he returned from another trip to Provence, and found that a son had been born to him, he changed the child’s name to Francesco, Francis, apparently as a tribute to Pica. The boy grew up in one of the loveliest regions of Italy, and never lost his affection for the Umbrian landscape and sky. He learned Italian and French from his parents, and Latin from the parish priest; he had no further formal schooling, but soon entered his father’s business. He disappointed Ser Pietro by showing more facility in spending money than in making it. He was the richest youth in town, and the most generous; friends flocked about him, ate and drank with him, and sang with him the songs of the troubadours; Francis wore, now and then, a parti-colored minstrel’s suit.36 He was a good-looking boy, with black eyes and hair and kindly face, and a melodious voice. His early biographers protest that he had no relations with the other sex, and, indeed, knew only two women by sight;37 but this surely does Francis some injustice. Possibly, in those formative years, he heard from his father about the Albigensian and Waldensian heretics of southern France, and their new-old gospel of evangelical poverty.

In 1202 he fought in the Assisian army against Perugia, was made prisoner, and spent a year in meditative captivity. In 1204 he joined as a volunteer the army of Pope Innocent III. At Spoleto, lying in bed with a fever, he thought he heard a voice asking him: “Why do you desert the Lord for the servant, the Prince for his vassal?” “Lord,” he asked, “what do you wish me to do?” The voice answered, “Go back to your home; there it shall be told you what you are to do.”38 He left the army and returned to Assisi. Now he showed ever less interest in his father’s business, ever more in religion. Near Assisi was a poor chapel of St. Damian. Praying there in February, 1207, Francis thought he heard Christ speak to him from the altar, accepting his life and soul as an oblation. From that moment he felt himself dedicated to a new life. He gave the chapel priest all the money he had with him, and went home. One day he met a leper, and turned away in revulsion. Rebuking himself for unfaithfulness to Christ, he went back, emptied his purse into the leper’s hand, and kissed the hand; this act, he tells us, marked an era in his spiritual life.39 Thereafter he frequently visited the dwellings of the lepers, and brought them alms.

Shortly after this experience he spent several days in or near the chapel, apparently eating little; when he appeared again in Assisi he was so thin, haggard, and pale, and his clothes so tattered, his mind so bewildered, that the urchins in the public square cried out, Pazzo! Pazzo!—“A madman! A madman!” There his father found him, called him a half-wit, dragged him home, and locked him in a closet. Freed by his mother, Francis hurried back to the chapel. The angry father overtook him, upbraided him for making his family a public jest, reproached him for making so little return on the money spent in his rearing, and bade him leave the town. Francis had sold his personal belongings to support the chapel; he handed the proceeds to his father, who accepted them; but he would not recognize the authority of his father to command one who now belonged to Christ. Summoned before the tribunal of the bishop in the Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore, he presented himself humbly, while a crowd looked on in a scene made memorable by Giotto’s brush. The bishop took him at his word, and bade him give up all his property. Francis retired to a room in the episcopal palace, and soon reappeared stark naked; he laid his bundled clothing and a few remaining coins before the bishop, and said: “Until this time I have called Pietro Bernadone my father, but now I desire to serve God. That is why I return to him this money … as well as my clothing, and all that I have had from him; for henceforth I desire to say nothing else than ‘Our Father, Who art in heaven.’”40 Bernadone carried off the clothing, while the bishop covered the shivering Francis with his mantle. Francis returned to St. Damian’s, made himself a hermit’s robe, begged his food from door to door, and with his hands began to rebuild the crumbling chapel. Several of the townspeople came to aid him, and they sang together as they worked.

In February, 1209, as he was hearing Mass, he was struck by the words which the priest read from the instructions of Jesus to the apostles:

And as ye go, preach, saying, “The kingdom of heaven is at hand.” Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils. Freely ye have received, freely give. Provide neither gold nor silver nor brass in your purses, nor scrip for your journey, neither two coats, neither shoes, nor a staff. (Matt. x, 7–10.)

It seemed to Francis that Christ Himself was speaking, and directly to him. He resolved to obey those words literally—to preach the kingdom of heaven, and possess nothing. He would go back across the 1200 years that had obscured the figure of Christ, and would rebuild his life on that divine exemplar.

So, that spring, braving all ridicule, he stood in the squares of Assisi and nearby towns and preached the gospel of poverty and Christ. Revolted by the unscrupulous pursuit of wealth that marked the age, and shocked by the splendor and luxury of some clergymen, he denounced money itself as a devil and a curse, bade his followers despise it as dung,41 and called upon men and women to sell all that they had, and give to the poor. Small audiences listened to him in wonder and admiration, but most men passed him by as a fool in Christ. The good bishop of Assisi protested, “Your way of living without owning anything seems to me very harsh and difficult”; to which Francis replied, “My lord, if we possessed property we should need arms to defend it.”42 Some hearts were moved; twelve men offered to follow his doctrine and his way; he welcomed them, and gave them the above-quoted words of Christ as their commission and their rule. They made themselves brown robes, and built themselves cabins of branches and boughs. Daily they and Francis, rejecting the old monastic isolation, went forth, barefoot and penniless, to preach. Sometimes they would be absent for several days, and sleep in haylofts, or leper hospitals, or under the porch of a church. When they returned, Francis would wash their feet and give them food.

They greeted one another, and all whom they met on the road, with the ancient Oriental salutation: “The Lord give thee peace.” They were not yet named Franciscans. They called themselves Fratres minores, Friars Minor, or Minorites; friars as meaning brothers rather than priests, minor as being the least of Christ’s servants, and never wielding, but always under, superior authority; they were to hold themselves subordinate to even the lowliest priest, and to kiss the hand of any priest they met. Very few of them, in this first generation of the order, were ordained; Francis himself was never more than deacon. In their own little community they served one another, and did manual work; and no idler was long tolerated in the group. Intellectual study was discouraged; Francis saw no advantage in secular knowledge except for the accumulation of wealth or the pursuit of power; “my brethren who are led by desire of learning will find their hands empty in the day of tribulation.”43 He scorned historians, who perform no great deed themselves, but receive honors for recording the great deeds of others.44 Anticipating Goethe’s dictum that knowledge that does not lead to action is vain and poisonous, Francis said, Tantum homo habet de scientia, quantum operatur —“A man has only so much knowledge as he puts to work.”45 No friar was to own a book, not even a psalter. In preaching they were to use song as well as speech; they might even, said Francis, imitate the jongleurs, and become ioculatores Dei, gleemen of God.46

Sometimes the friars were derided, beaten, or robbed of almost their last garment. Francis bade them offer no resistance. In many cases the miscreants, astonished at what seemed a superhuman indifference to pride and property, begged forgiveness and restored their thefts.47 We do not know if the following specimen of the Little Flowers of St. Francis is history or legend, but it portrays the ecstatic piety that runs through all that we hear of the saint:

One winter’s day as Francis was going from Perugia, suffering sorely from the bitter cold, he said: “Friar Leo, although the Friars Minor give good examples of holiness and edification, nevertheless write and note down diligently that perfect joy is not to be found therein.” And Francis went his way a little farther, and said: “O Friar Leo, even though the Friars Minor gave sight to the blind, made the crooked straight, cast out devils, made the deaf to hear and the lame to walk … and raised to life those who had lain four days in the grave —write: perfect joy is never found there.” And he journeyed on a little while, and cried aloud: “O Friar Leo, if the Friar Minor knew all tongues and sciences and all the Scriptures, so that he could foretell and reveal not only future things but even the secrets of the conscience and the soul—write: perfect joy is not there.” … Yet a little farther he went, and cried again aloud: “O Friar Leo, although the Friar Minor were skilled to preach so well that he should convert all infidels to Christ—write: not there is perfect joy.” And when this fashion of talk had continued for two miles, Friar Leo asked: … “Father, prithee in God’s name tell me where is perfect joy to be found?” And Francis answered him: “When we are come to St. Mary of the Angels” [then the Franciscan chapel in Assisi], “wet through with rain, frozen with cold, foul with mire, and tormented with hunger, and when we knock at the door, and the doorkeeper comes in a rage and says, ‘Who are you?’ and we say, ‘We are two of your friars,’ and he answers, ‘You lie, you are rather two knaves who go about deceiving the world and stealing the alms of the poor. Begone!’ and he opens not to us, and makes us stay outside hungry and cold all night in the rain and snow; then, if we endure patiently such cruelty … without complaint or mourning, and believe humbly and charitably that it is God who made the doorkeeper rail against us—O Friar Leo, write: there is perfect joy! And if we persevere in our knocking; and he issues forth, and angrily drives us away, abusing us and smiting us on the cheek, saying, ‘Go hence, you vile thieves!’—if this we suffer patiently with love and gladness, write, O Friar Leo: this is perfect joy! And if, constrained by hunger and by cold, we knock once more and pray with many tears that he open to us for the love of God, and he … issues forth with a ‘big knotted stick and seizes us by our cowls and flings us on the ground, and rolls us in the snow, bruising every bone in our bodies with that heavy club; if we, thinking on the agony of the blessed Christ, endure all these things patiently and joyously for love of Him—write, O Friar Leo, that here and in this is found perfect joy.”48

The remembrance of his early life of indulgence gave him a haunting sense of sin; and if we may believe the Little Flowers he sometimes wondered whether God would ever forgive him. A touching story tells how, in the early days of the order, when they could find no breviary from which to read the divine office, Francis extemporized a litany of contrition, and bade Brother Leo repeat after him words accusing Francis of sin. Leo at each sentence tried to repeat the accusation, but found himself saying, instead, “The mercy of God is infinite.”49 On another occasion, just convalescing from quartan fever, Francis had himself dragged naked before the people in the market place of Assisi, and commanded a friar to throw a full dish of ashes into his face; and to the crowd he said: “You believe me to be a holy man, but I confess to God and you that I have in this my infirmity eaten meat and broth made with meat.”50 The people were all the more convinced of his sanctity. They told how a young friar had seen Christ and the Virgin conversing with him; they attributed many miracles to him, and brought their sick and “possessed” to him to be healed. His charity became a legend. He could not bear to see others poorer than himself; he so often gave to the passing poor the garments from his back that his disciples found it hard to keep him clothed. Once, says the probably legendary Mirror of Perfection,51

when he was returning from Siena he came across a poor man on the way, and said to a fellow monk: “We ought to return this mantle to its owner. For we received it only as a loan until we should come upon one poorer than ourselves…. It would be counted to us as a theft if we should not give it to him who is more needy.”

His love overflowed from men to animals, to plants, even to inanimate things. The Mirror of Perfection, unverified, ascribes to him a kind of rehearsal for his later Canticle of the Sun:

In the morning, when the sun rises, every man ought to praise God, who created it for our use…. When it becomes night, every man ought to give praise on account of Brother Fire, by which our eyes are then enlightened; for we be all, as it were, blind; and the Lord by these two, our brothers, doth enlighten our eyes.

He so admired fire that he hesitated to extinguish a candle; the fire might object to being put out. He felt a sensitive kinship with every living thing. He wished to “supplicate the Emperor” (Frederick II, a great hunter of birds) “to tell him, for the love of God and me, to make a special law that no man should take or kill our sisters the larks, nor do them any harm; likewise that all the podestas or mayors of the towns, and the lords of castles and villages, should require men every year on Christmas Day to throw grain outside the cities and castles, that our sisters the larks, and other birds, may have something to eat.”52 Meeting a youth who had snared some turtle doves and was taking them to market, Francis persuaded the boy to give them to him; the saints built nests for them, “that ye may be fruitful and multiply”; they obeyed abundantly, and lived near the monastery in happy friendship with the monks, occasionally snatching food from the table at which these were eating.53 A score of legends embroidered this theme. One told how Francis preached to “my little sisters the birds” on the road between Cannora and Bevagna; and “those that were on the trees flew down to hear him, and stood still the while St. Francis made an end of his sermon.”

My little sisters the birds, much are ye beholden to God your Creator, and always and in every place ye ought to praise Him for that He hath given you a double and triple vesture. He hath given you freedom to go into any place…. Moreover ye sow not, neither do ye reap, and God feedeth you and giveth you the rivers and the fountains for your drink; He giveth you the mountains and the valleys for your refuge, and the tall trees wherein to build your nests; and for as much as ye can neither spin nor sew, God clotheth you and your children…. Therefore beware, little sisters mine, of the sin of ingratitude, but ever strive to praise God.54

We are assured by Friars James and Masseo that the birds bowed in reverence to Francis, and would not depart until he had blessed them. The Fioretti or Little Flowers from which this story comes are an Italian amplification of a Latin Actus Beati Francisci (1323); they belong less to factual history than to literature; but there they rank among the most engaging compositions of the Age of Faith.

Having been advised that he needed papal permission to establish a religious order, Francis and his twelve disciples went to Rome in 1210, and laid their request and their rule before Innocent III. The great Pope gently counseled them to defer formal organization of a new order until time should test the practicability of the rule. “My dear children,” he said, “your life appears to me too severe. I see indeed that your fervor is great … but I ought to consider those who will come after you, lest your mode of life be beyond their strength.”55 Francis persisted, and the Pope finally yielded—incarnate strength to incarnate faith. The friars took the tonsure, submitted themselves to the hierarchy, and received from the Benedictines of Mt. Subasio, near Assisi, the chapel of St. Mary of the Angels, so small—some ten feet long-that it came to be called Portiuncula—“little portion.” The friars built themselves huts around the chapel, and these huts formed the first monastery of the First Order of St. Francis.

Now not only did new members join the order, but, to the joy of the saint, a wealthy girl of eighteen, Clara dei Sciffi, asked his permission to form a Second Order of St. Francis, for women (1212). Leaving her home, she vowed herself to poverty, chastity, and obedience, and became the abbess of a Franciscan convent built around the chapel of St. Damian. In 1221 a Third Order of St. Francis—the Tertiaries—was formed among laymen who, while not bound to the full Franciscan rule, wished to obey that rule as far as possible while living in the “world,” and to help the First and Second Orders with their labor and charity.

The ever more numerous Franciscans now (1211) brought their gospel to the towns of Umbria, and later to the other provinces of Italy. They uttered no heresy, but preached little theology; nor did they ask of their hearers the chastity, poverty, and obedience to which they themselves were vowed. “Fear and honor God,” they said, “praise and bless Him…. Repent… for you know that we shall soon die…. Abstain from evil, persevere in the good.” Italy had heard such words before, but seldom from men of such evident sincerity. Crowds came to their preaching; and one Umbrian village, learning of Francis’ approach, went out en masse to greet him with flowers, banners, and song.56 At Siena he found the city in civil war; his preaching brought both factions to his feet, and at his urging they ended their strife for a while.57 It was on these missionary tours in Italy that he contracted the malaria which was to bring him to an early death.

Nevertheless, encouraged by his Italian success, and knowing little of Islam, Francis resolved to go to Syria and convert the Moslems, even the sultan. In 1212 he sailed from an Italian port, but a storm cast his ship upon the Dalmatian coast, and he was forced to return to Italy; legend, however, tells how “St. Francis converted the soldan of Babylon.”58 In the same year, says a story probably also mythical, he went to Spain to convert the Moors; but on arrival he fell so ill that his disciples had to bring him back to Assisi. Another questionable narrative takes him to Egypt; he passed unharmed, we are told, into the Moslem army that was resisting the Crusaders at Damietta; he offered to go through fire if the sultan would promise to lead his troops into the Christian faith in case Francis emerged unscathed; the sultan refused, but had the saint escorted safely to the Christian camp. Horrified by the fury with which the soldiers of Christ massacred the Moslem population at the capture of Damietta,59 Francis returned to Italy a sick and saddened man. To his chilling malaria, it is said, he added in Egypt an eye infection that would in later years almost destroy his sight.

During these long absences of the saint his followers multiplied faster than was good for his rule. His fame brought recruits who took the vows without due reflection; some came to regret their haste; and many complained that the rule was too severe. Francis made reluctant concessions. Doubtless, too, the expansion of the order, which had divided itself into several houses scattered through Umbria, made such demands upon him for administrative skill and tact as his mystic absorption could hardly meet. Once, we are told, when one monk spoke evil of another, Francis commanded him to eat a lump of ass’s dung so that his tongue should not relish evil any more; the monk obeyed, but his fellows were more shocked by the punishment than by the offense.60 In 1220 Francis resigned his leadership, bade his followers elect another minister-general, and thereafter counted himself a simple monk. A year later, however, disturbed by further relaxations of the original (1210) rule, he drew up a new rule—his famous “Testament”—aiming to restore full observance of the vow of poverty, and forbidding the monks to move from their huts at the Portiuncula to the more salubrious quarters built for them by the townspeople. He submitted this rule to Honorius III, who turned it over to a committee of prelates for revision; when it came from their hands it made a dozen obeisances to Francis, and as many relaxations of the rule. The predictions of Innocent III had been verified.

Reluctantly but humbly obedient, Francis now gave himself to a life of mostly solitary contemplation, asceticism, and prayer. The intensity of his devotion and his imagination occasionally brought him visions of Christ, or Mary, or the apostles. In 1224, with three disciples, he left Assisi, and rode across hill and plain to a hermitage on Mt. Verna, near Chiusi. He secluded himself in a lonely hut beyond a deep ravine, allowed none but Brother Leo to visit him, and bade him come only twice a day, and not to come if he received no answer to his call of approach. On September 14, 1224, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, after a long fast and a night spent in vigil and prayer, Francis thought he saw a seraph coming down from the sky, bearing an image of the crucified Christ. When the vision faded he felt strange pains, and discovered fleshy excrescences on the palms and backs of his hands, on the soles and tops of his feet, and on his body, resembling in place and color the wounds—stigmata—presumably made by the nails that were believed to have bound the extremities of Jesus to the cross, and by the lance that had pierced His side.*

Francis returned to the hermitage, and to Assisi. A year after the appearance of the stigmata he began to lose his sight. On a visit to St. Clara’s nunnery he was struck completely blind. Clara nursed him back to sight, and kept him at St. Damian’s for a month. There one day in 1224, perhaps in the joy of convalescence, he composed, in Italian poetic prose, his “Canticle of the Sun”:62

Most High, Omnipotent, Good Lord.

Thine be the praise, the glory, the honor, and all benediction;

to Thee alone, Most High, they are due,

and no man is worthy to mention Thee.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, with all Thy creatures,

above all Brother Sun,

who gives the day and lightens us therewith.

And he is beautiful and radiant with great splendor;

of Thee, Most High, he bears similitude.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of Sister Moon and the stars;

in the heaven hast Thou formed them, clear and precious and comely.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of Brother Wind,

and of the air, and the cloud, and of fair and of all weather,

by the which Thou givest to Thy creatures sustenance.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of Sister Water,

which is much useful and humble and precious and pure.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of Brother Fire,

by which Thou hast lightened the night,

and he is beautiful and joyful and robust and strong.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of our Sister Mother Earth,

which sustains and hath us in rule,

and produces divers fruits with colored flowers and herbs.

Be Thou praised, my Lord, of those who pardon for Thy love

and endure sickness and tribulations.

Blessed are they who will endure it in peace,

for by Thee, Most High, they shall be crowned.

In 1225 some physicians at Rieti, having to no good effect anointed his eyes with “the urine of a virgin boy,” resorted to drawing a rod of white-hot iron across his forehead. Francis, we are told, appealed to “Brother Fire: you are beautiful above all creatures; be favorable to me in this hour; you know how much I have always loved you”; he said later that he had felt no pain. He recovered enough sight to set forth on another preaching tour. He soon broke down under the hardships of travel; malaria and dropsy crippled him, and he was taken back to Assisi.

Despite his protestations he was put to bed in the episcopal palace. He asked the doctor to tell him the truth, and was told that he could barely survive the autumn. He astonished everyone by beginning to sing. Then, it is said, he added a stanza to his Canticle of the Sun:

Be praised, Lord, for our Sister Bodily Death, from whom

no man can escape.

Alas for them who die in mortal sin;

Blessed are they who are found in Thy holy will,

for the second death will not work them harm.63

It is said that in these last days he repented of his asceticism, as having “offended his brother the body.”64 When the bishop was called away Francis persuaded the monks to remove him to Portiuncula. There he dictated his will, at once modest and commanding: he bade his followers be content with “poor and abandoned churches,” and not to accept habitations out of harmony with their vows of poverty; to surrender to the bishop any heretic or recreant monk in the order; and never to change the rule.65

He died October 3, 1226, in the forty-fifth year of his age, singing a psalm. Two years later the Church named him a saint. Two other leaders dominated that dynamic age: Innocent III and Frederick II. Innocent raised the Church to its greatest height, from which in a century it fell. Frederick raised the Empire to its greatest height, from which in a decade it fell. Francis exaggerated the virtues of poverty and ignorance, but he reinvigorated Christianity by bringing back into it the spirit of Christ. Today only scholars know of the Pope and the Emperor, but the simple saint reaches into the hearts of millions of men.

The order that he had founded numbered at his death some 5000 members, and had spread into Hungary, Germany, England, France, and Spain. It proved the bulwark of the Church in winning northern Italy from heresy back to Catholicism. Its gospel of poverty and illiteracy could be accepted by only a small minority; Europe insisted on traversing the exciting parabola of wealth, science, philosophy, and doubt. Meanwhile even the modified rule that Francis had so unwillingly accepted was further relaxed (1230); men could not be expected to stay long, and in needed number, on the heights of the almost delirious asceticism that had shortened Francis’ life. With a milder rule the Friars Minor grew by 1280 to 200,000 monks in 8000 monasteries. They became great preachers, and by their example led the secular clergy to take up the custom of preaching, heretofore confined to bishops. They produced saints like St. Bernardino of Siena and St. Anthony of Padua, scientists like Roger Bacon, philosophers like Duns Scotus, teachers like Alexander of Hales. Some became agents of the Inquisition; some rose to be bishops, archbishops, popes; many undertook dangerous missionary enterprises in distant and alien lands. Gifts poured in from the pious; some leaders, like Brother Elias, learned to like luxury; and though Francis had forbidden rich churches, Elias raised to his memory the imposing basilica that still crowns the hill of Assisi. The paintings of Cimabue and Giotto there were the first products of an immense and enduring influence of St. Francis, his history and his legend, on Italian art.

Many Minorites protested against the relaxation of Francis’ rule. As “Spirituals” or “Zealots” they lived in hermitages or small convents in the Apennines, while the great majority of Franciscans preferred spacious monasteries. The Spirituals argued that Christ and His apostles had possessed no property; St. Bonaventura agreed; Pope Nicholas III approved the proposition in 1279; Pope John XXII pronounced it false in 1323; and thereafter those Spirituals who persisted in preaching it were suppressed as heretics. A century after the death of Francis his most loyal followers were burned at the stake by the Inquisition.

IV. ST. DOMINIC

It is unjust to Dominic that his name should suggest the Inquisition. He was not its founder, nor was he responsible for its terrors; his own activity was to convert by example and preaching. He was of sterner stuff than Francis, but revered him as the saintlier saint; and Francis loved him in return. Essentially their work was the same: each organized a great order of men devoted not to self-salvation in solitude but to missionary work among Christians and infidels. Each took from the heretics their most persuasive weapons—the praise of poverty and the practice of preaching. Together they saved the Church.

Domingo de Guzman was born at Calaruega in Castile (1170). Brought up by an uncle priest, he was one of thousands who in those days took Christianity to heart. When famine struck Palencia he is said to have sold all his goods, even his precious books, to feed the poor. He became an Augustinian canon regular in the cathedral of Osma, and in 1201 accompanied his bishop on a mission to Toulouse, then a center of the Albigensian heresy. Their very host was an Albigensian; it may be a legend that Dominic converted him overnight. Inspired by the advice of the bishop and the example of some heretics, Dominic adopted the life of voluntary poverty, went about barefoot, and strove peaceably to bring the people back to the Church. At Montpellier he met three papal legates—Arnold, Raoul, and Peter of Castelnau. He was shocked by their rich dress and luxury, and attributed to this their confessed failure to make headway against the heretics. He rebuked them with the boldness of a Hebrew prophet: “It is not by the display of power and pomp, nor by cavalcades of retainers and richly houseled palfreys, nor by gorgeous apparel, that the heretics win proselytes; it is by zealous preaching, by apostolic humility, by austerity, by holiness.”66 The shamed legates, we are told, dismissed their equipage and shed their shoes.

For ten years (1205–16) Dominic remained in Languedoc, preaching zealously. The only mention of him in connection with physical persecution tells how, at a burning of heretics, he saved one from the flames.67 Some of his order proudly called him, after his death, Persecutor haereticorum—not necessarily the persecutor but the pursuer of heretics. He gathered about him a group of fellow preachers, and their effectiveness was such that Pope Honorius III (1216) recognized the Friars Preachers as a new order, and approved the rule drawn up for it by Dominic. Making his headquarters at Rome, Dominic gathered recruits, taught them, inspired them with his almost fanatical zeal, and sent them out through Europe as far east as Kiev, and into foreign lands, to convert Christendom and heathendom to Christianity. At the first general chapter of the Dominicans at Bologna in 1220, Dominic persuaded his followers to adopt by unanimous vote the rule of absolute poverty. There, a year later, he died.

Like the Franciscans, the Dominicans spread everywhere as wandering, mendicant friars. Matthew Paris describes them in the England of 1240:

Very sparing in food and raiment, possessing neither gold nor silver nor anything of their own, they went through cities, towns, and villages, preaching the Gospel… living together by tens or sevens … thinking not of the morrow, nor keeping anything for the next morning…. Whatsoever was left over from their table of the alms give them, this they gave forthwith to the poor. They went shod only with the Gospel, they slept in their clothes on mats, and laid stones for pillows under their heads.68

They took an active, and not always a gentle, part in the work of the Inquisition. They were employed by the popes in high posts and diplomatic missions. They entered the universities and produced the two giants of Scholastic philosophy, Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas; it was they who saved the Church from Aristotle by transforming him into a Christian. Together with the Franciscans, the Carmelites, and the Austin Friars they revolutionized the monastic life by mingling with the common people in daily ministrations, and raised monasticism in the thirteenth century to a power and beauty which it had never attained before.

A large perspective of monastic history does not bear out the exaggerations of moralists nor the caricatures of satirists. Many cases of monastic misconduct can be cited; they draw attention precisely because they are exceptional; and which of us is so saintly that he may demand an untarnished record from any class of men? The monks who remained faithful to their vows—who lived in obscure poverty, chastity, and piety—eluded both gossip and history; virtue makes no news, and bores both readers and historians. We hear of “sumptuous edifices” possessed by Franciscan monks as early as 1249, and in 1271 Roger Bacon, whose hyperboles often forfeited him a hearing, informed the pope that “the new orders are now horribly fallen from their original dignity.”69 But this is hardly the picture that we get from Fra Salimbene’s candid and intimate Chronicle (1288?). Here a Franciscan monk takes us behind the scenes and into the daily career of his order. There are peccadilloes here and there, and some quarrels and jealousy; but over all that arduously inhibited life hovers an atmosphere of modesty, simplicity, brotherliness, and peace.70 If, occasionally, a woman enters this story, she merely brings a touch of grace and tenderness into narrow and lonely lives. Hear a sample of Fra Salimbene’s guileless chatter:

There was a certain youth in the convent of Bologna who was called Brother Guido. He was wont to snore so mightily in his sleep that no man could rest in the same house with him, wherefore he was set to sleep in a shed among the wood and straw; yet even so the brethren could not escape him, for the sound of that accursed rumbling echoed throughout the whole convent. So all the priests and discreet brethren gathered together … and it was decreed by a formal sentence that he should be sent back to his mother, who had deceived the order, since she knew all this of her son before he was received among us. Yet was he not sent back forthwith, which was the Lord’s doing…. For Brother Nicholas, considering within himself that the boy was to be cast out through a defect of nature, and without guilt of his own, called the lad daily about the hour of dawn to come and serve him at Mass; and at the end of the Mass the boy would kneel at his bidding behind the altar, hoping to receive some grace of him. Then would Brother Nicholas touch the boy’s face and nose with his hands, desiring, by God’s gifts, to bestow on him the boon of health. In brief, the boy was suddenly and wholly healed, without further discomfort to the brethren. Thenceforth he slept in peace and quiet, like any dormouse.71

V. THE NUNS

As early as the time of St. Paul it had been the custom, in Christian communities, for widows and other lonely or devout women to give some of all of their days and their property to charitable work. In the fourth century some women, emulating monks, left the world and lived the life of religious in solitude or in communities, under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. About 530 St. Benedict’s twin sister Scholastica established a nunnery near Monte Cassino under his guidance and rule. From that time Benedictine convents spread through Europe, and Benedictine nuns became almost as numerous as Benedictine monks. The Cistercian Order opened its first convent in 1125, its most famous one, Port Royal, in 1204; by 1300 there were 700 Cistercian nunneries in Europe.72 In these older orders most of the nuns came from the upper classes,73 and nunneries were too often the repository of women for whom their male relations had no room or taste. In 458 the Emperor Majorian had to forbid parents to rid themselves of supernumerary daughters by compelling them to enter a convent.74 Entry into Benedictine nunneries usually required a dowry, though the Church prohibited any but voluntary offerings.75 Hence a prioress, like Chaucer’s, could be a woman of proud breeding and large responsibilities, administering a spacious domain as the source of her convent’s revenues. In those days a nun was usually called not Sister but Madame.

St. Francis revolutionized conventual as well as monastic institutions. When Santa Clara came to him in 1212, and expressed her wish to found for women such an order as he had founded for men, he overlooked canonical regulations and, though himself only a deacon, received her vows, accepted her into the Franciscan Order, and commissioned her to organize the Poor Clares. Innocent III, with his usual ability to forgive infractions of the letter by the spirit, confirmed the commission (1216). Santa Clara gathered about her some pious women who lived in communal poverty, wove and spun, nursed the sick, and distributed charity. Legends formed around her almost as fondly as around Francis himself. Once, we are told, a pope

went to her convent to hear her discourse of divine and celestial things…. Santa Clara had the table laid, and set loaves of bread thereon that the Holy Father might bless them…. Santa Clara knelt down with great reverence, and besought him to be pleased to bless the bread…. The Holy Father answered: “Sister Clare, most faithful one, I desire that thou shouldst bless this bread, and make over it the sign of the most holy cross of Christ, to which thou hast completely devoted thyself.” And Santa Clara said: “Most Holy Father, forgive me, but I should merit great reproof if, in the presence of the Vicar of Christ, I, who am a poor, vile woman, should presume to give such benediction.” And the Pope answered: “To the end that this be not imputed to thy presumption but to the merit of obedience, I command thee, by holy obedience, that thou … bless this bread in the name of God.” And then Santa Clara, even as a true daughter of obedience, devoutly blessed the bread with the sign of the most holy cross. Marvelous to tell! forthwith on all those loaves the sign of the cross appeared figured most beautifully. And the Holy Father, when he saw this miracle, partook of the bread and departed, thanking God and leaving his blessing with Santa Clara.76

She died in 1253, and was canonized soon afterward. Franciscan monks in divers localities organized similar groups of Clarissi, or Poor Clares. The other mendicant orders—Dominicans, Augustinians, Carmelites—also established a “second order” of nuns; and by 1300 Europe had as many nuns as monks. In Germany the nunneries tended to be havens of intense mysticism; in France and England they were often the refuge of noble ladies “converted” from the world, or deserted, disappointed, or bereaved. The Ancren Riwle—i.e., the Rule of the Anchorites—reveals the mood expected of English nuns in the thirteenth century. It may have been written by Bishop Poore probably for a convent at Tarrant in Dorsetshire. It is darkened with much talk of sin and hell, and some blasphemous abuse of the female body;77 but a tone of fine sincerity redeems it, and it is among the oldest and noblest specimens of English prose.78

It would be a simple matter to gather, from ten centuries, some fascinating instances of conventual immorality. A number of nuns had been cloistered against their wills,79 and found it uncomfortable to be saints. Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury and Bishop Egbert of York deemed it necessary to forbid the seduction of nuns by abbots, priests, and bishops.80 Bishop Ivo of Chartres (1035–1115) reported that the nuns of St. Fara’s Convent were practicing prostitution; Abélard (1079–1142) gave a similar picture of some French convents of his time; Pope Innocent III described the convent of St. Agatha as a brothel that infected the whole surrounding country with its evil life and repute.81 Bishop Rigaud of Rouen (1249) gave a generally favorable report of the religious groups in his diocese, but told of one nunnery in which, out of thirty-three nuns and three lay sisters, eight were guilty, or suspected, of fornication, and “the prioress is drunk almost any night.”82 Boniface VIII (1300) tried to improve conventual discipline by decreeing strict claustration, or seclusion from the world; but the decree could not be enforced.83 At one nunnery in the diocese of Lincoln, when the bishop came to deposit this papal bull, the nuns threw it at his head, and vowed they would never obey it;84 such isolation had probably not been in their vows. The prioress in Chaucer’s Tales had no business there, for the Church had forbidden nuns to go on pilgrimage.85

If history had been as careful to note instances of obedience to conventual rules as to record infractions, we should probably be able to counter each sinful lapse with a thousand examples of fidelity. In many cases the rules were inhumanly severe, and merited violation. Carthusian and Cistercian nuns were required to keep silence except when speech was indispensable—a command sorely uncongenial to the gentle sex. Usually the nuns attended to their own needs of cleaning, cooking, washing, sewing; they made clothing for monks and the poor, linen for the altar, vestments for the priest; they wove and embroidered hangings and tapestries, and depicted on them, with nimble fingers and patient souls, half the history of the world. They copied and illuminated manuscripts; they received children to board, and taught them letters, hygiene, and domestic arts; for centuries they provided the only higher education open to girls. Many of them served as nurses in hospitals. They rose at midnight for prayers, and again before dawn, and recited the canonical hours. Many days were fast days, on which they ate no food till the evening meal.

Let us hope that these hard rules were sometimes infringed. If we look back upon the nineteen centuries of Christianity, with all their heroes, kings, and saints, we shall find it difficult to list many men who came so close to Christian perfection as the nuns. Their lives of quiet devotion and cheerful ministration have made many generations blessed. When all the sins of history are weighed in the balance, the virtues of these women will tip the scale against them, and redeem our race.

VI. THE MYSTICS

Many such women could be saints because they felt divinity closer to them than hands and feet. The medieval imagination was so stimulated by all the forces of word, picture, statue, ceremony, even by the color and quantity of light, that supersensory visions came readily, and the believing soul felt itself breaking through the bounds of nature to the supernatural. The human mind itself, in all the mystery of its power, seemed a supernatural and unearthly thing, surely akin to—a blurred image and infinitesimal fraction of—the Mind behind and in the matter of the world; so the top of the mind might touch the foot of the throne of God. In the ambitious humility of the mystic the hope burned that a soul unburdened of sin and uplifted with prayer might rise on the wings of grace to the Beatific Vision and a divine companionship. That vision could never be attained through sensation, reason, science, or philosophy, which were bound to time, the many, and the earth, and could never reach to the core and power and oneness of the universe. The problem of the mystic was to cleanse the soul as an internal organ of spiritual perception, to wash away from it all stain of selfish individuality and illusory multiplicity, to widen its reach and love to the uttermost inclusion, and then to see, with clear and disembodied sight, the cosmic, eternal, and divine, and thereby to return, as from a long exile, to union with the God from Whom birth had meant a penal severance. Had not Christ promised that the pure in heart would see God?

Mystics, therefore, appeared in every age, every religion, and every land. Greek Christianity abounded in them despite the Hellenic legacy of reason. St. Augustine was a mystic fountain for the West; his Confessions constituted a return of the soul from created things to God; seldom had any mortal so long conversed with the Deity. St. Anselm the statesman, St. Bernard the organizer, upheld the mystical approach against the rationalism of Roscelin and Abélard. When William of Champeaux was driven from Paris by the logic of Abélard, he founded in a suburb (1108) the Augustinian abbey of St. Victor as a school of theology; and his successors there, Hugh and Richard, ignoring the perilous adventure of young philosophy, based religion not on argument but on the mystical experience of the divine presence. Hugh (d. 1141) saw supernatural sacramental symbols in every phase of creation; Richard (d. 1173) rejected logic and learning, preferred the “heart” to the “head” à la Pascal, and described with learned logic the mystical rise of the soul to God.

The passion of Italy kindled mysticism into a gospel of revolution. Joachim of Flora—Giovanni dei Gioacchini di Fiori—a noble of Calabria, developed a longing to see Palestine. Impressed on the way by the misery of the people, he dismissed his retinue and continued as a humble pilgrim. Legend tells how he passed an entire Lent in an old well on Mt. Tabor; how, on Easter Sunday, a great splendor appeared to him, and filled him with such divine light that he understood at once all the Scriptures, all the future and the past. Returning to Calabria, he became a Cistercian monk and priest, thirsted for austerity, and retired to a hermitage. Disciples gathered, and he formed them into a new Order of Flora, whose rule of poverty and prayer was approved by Celestine III. In 1200 he sent to Innocent III a series of works which he had written, he said, under divine inspiration, but which, nevertheless, he submitted for papal censorship. Two years later he died.

His writings were based on the Augustinian theory—widely accepted in orthodox circles—that a symbolic concordance existed between the events of the Old Testament and the history of Christendom from the birth of Christ to the establishment of the Kingdom of Heaven on earth. Joachim divided the history of man into three stages: the first, under the rule of God the Father, ended at the Nativity; the second, ruled by the Son, would last, according to apocalyptic calculations, 1260 years; the third, under the Holy Ghost, would be preceded by a time of troubles, of war and poverty and ecclesiastical corruption, and would be ushered in by the rise of a new monastic order which would cleanse the Church, and would realize a worldwide utopia of peace, justice, and happiness.86

Thousands of Christians, including men high in the Church, accepted Joachim’s claim to divine inspiration, and looked hopefully to 1260 as the year of the Second Advent. The Spiritual Franciscans, confident that theirs was the new Order, took courage from Joachim’s teachings; and when they were outlawed by the Church they carried on their propaganda through writings published under his name. In 1254 an edition of Joachim’s main works appeared under the title of The Everlasting Gospel, with a commentary proclaiming that a pope tainted with simony would mark the close of the Second Age, and that in the Third Age the need of sacraments and priests would be ended by the reign of universal love. The book was condemned by the Church; its presumptive author, a Franciscan monk Gherardo da Borgo, was imprisoned for life; but its circulation secretly continued, and deeply affected mystical and heretical thought in Italy and France from St. Francis to Dante—who placed Joachim in paradise.

Perhaps in excited expectation of the coming Kingdom, a mania of religious penitence flared up around Perugia in 1259, and swept through northern Italy. Thousands of penitents of every age and class marched in disorderly procession, dressed only in loincloths, weeping, praying God for mercy, and scourging themselves with leather thongs. Thieves and usurers fell in, and restored their illegal gains; murderers, catching the contagion of repentance, knelt before their victims’ kin and begged to be slain; prisoners were released, exiles were recalled, enmities were healed. The movement spread through Germany into Bohemia; and for a time it seemed that a new and mystical faith, ignoring the Church, would inundate Europe. But in a little while the nature of man reasserted itself; new enmities developed, sinning and murder were renewed; and the Flagellant craze disappeared into the psychic recesses from which it had emerged.87

The mystic flame burned less fitfully in Flanders. A priest of Liege, Lambert le Bégue (i.e., the stutterer), established in 1184 on the Meuse a house for women who, without taking monastic vows, wished to live together in small semi-communistic groups, supporting themselves by weaving wool and making lace. Similar maisons-Dieu, or houses of God, were established for men. The men called themselves Beghards, the women Beguines. These communities, like the Waldenses, condemned the Church for owning property, and themselves practiced a voluntary poverty. A similar sect, the Brethren of the Free Spirit, appeared about 1262 in Augsburg, and developed in the cities along the Rhine. Both movements claimed a mystical inspiration which absolved them from ecclesiastical control, even from state or moral law.88 State and Church combined to suppress them; they went underground, emerged repeatedly under new names, and contributed to the origin and fervor of the Anabaptists and other radical sects in the Reformation.

Germany became the favorite land of mysticism in the West. Hildegarde of Bingen (1099–1179), the “Sibyl of the Rhine,” lived all but eight of her eighty-two years as a Benedictine nun, and ended as abbess of a convent on the Rupertsberg. She was an unusual mixture of administrator and visionary, pietist and radical, poet and scientist, physician and saint. She corresponded with popes and kings, always in a tone of inspired authority, and in Latin prose of masculine power. She published several books of visions (Scivias), for which she claimed the collaboration of the Deity; the clergy were chagrined to hear it, for these revelations were highly critical of the wealth and corruption of the Church. Said Hildegarde, in accents of eternal hope:

Divine justice shall have its hour… the judgments of God are about to be accomplished; the Empire and the Papacy, sunk into impiety, shall crumble away together…. But upon their ruins shall appear a new nation…. The heathen, the Jews, the worldly and the unbelieving, shall be converted together; springtime and peace shall reign over a regenerated world, and the angels will return with confidence to dwell among men.89

A century later Elizabeth of Thuringia (1207–31) aroused Hungary with her brief life of ascetic sanctity. Daughter of King Andrew, she was married at thirteen to a German prince, was a mother at fourteen, a widow at twenty. Her brother-in-law despoiled her and drove her away penniless. She became a wandering pietist, devoted to the poor; she housed leprous women and washed their wounds. She too had heavenly visions, but she gave them no publicity, and claimed no supernatural powers. Meeting the fiery inquisitor Conrad of Marburg, she was morbidly fascinated by his merciless devotion to orthodoxy; she became his obedient slave; he beat her for the slightest deviation from his concept of sanctity; she submitted humbly, inflicted additional austerities upon herself, and died of them at twenty-four.90 Her reputation for saintliness was so great that at her funeral half-mad devotees cut off her hair, ears, and nipples as sacred relics.91 Another Elizabeth entered the Benedictine nunnery of Schonau, near Bingen, at the age of twelve (1141), and lived there till her death in 1165. Bodily infirmities and extreme asceticism generated trances, in which she received heavenly revelations from various dead saints, nearly all anticlerical. “The Lord’s vine has withered,” her guardian angel told her; “the head of the Church is ill, and her members are dead…. Kings of the earth! the cry of your iniquity has risen even to me.”92

Toward the end of this period the mystic tide ran high in Germany. Meister Eckhart, born about 1260, would come to his ripe doctrine in 1326, to his trial and death in 1327. His pupils Suso and Tauler would continue his mystic pantheism; and from that tradition of unecclesiastical piety would flow one source of the Reformation.

Usually the Church bore patiently with the mystics in her fold. She did not tolerate serious doctrinal deviations from the official line, or the anarchic individualism of some religious sects; but she admitted the claim of the mystics to a direct approach to God, and listened with good humor to saintly denunciations of her human faults. Many clergymen, even high dignitaries, sympathized with the critics, recognized the shortcomings of the Church, and wished that they too could lay down the contaminating tools and tasks of world politics and enjoy the security and peace of monasteries fed by the piety of the people and protected by the power of the Church. Perhaps it was such patient ecclesiastics who kept Christianity steady amid the delirious revelations that periodically threatened the medieval mind. As we read the mystics of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries it dawns upon us that orthodoxy was often a barrier to contagious superstitions, and that in one aspect the Church was belief—as the state was force—organized from chaos into order to keep men sane.

VII. THE TRAGIC POPE

When Gregory X came to the papacy in 1271 the Church was again at the summit of her power. He was a Christian as well as a pope: a man of peace and amity, seeking justice rather than victory. Hoping to regain Palestine by one united effort, he persuaded Venice, Genoa, and Bologna to end their wars; he secured the election of Rudolf of Hapsburg as Emperor, but soothed with courtesy and kindness the defeated candidates; and he reconciled Guelf and Ghibelline in factious Florence and Siena, saying to his Guelf supporters: “Your enemies are Ghibellines, but they are also men, citizens, and Christians.”93 He summoned the prelates of the Church to the Council of Lyons (1274); 1570 leading churchmen came; every great state sent a representative; the Greek emperor sent the heads of the Greek Church to reaffirm its submission to the Roman See; Latin and Greek churchmen sang together a Te Deum of joy. Bishops were invited to list the abuses that needed reform in the Church; they responded with startling candor;94 and legislation was passed to mitigate these evils. All Europe was magnificently united for a mighty effort against the Saracens. But on the way back to Rome Gregory died (1276). His successors were too busy with Italian politics to carry out his plans.

Nevertheless when Boniface VIII was chosen pope in 1294 the papacy was still the strongest government in Europe, the best organized, the best administered, the richest in revenue. It was the misfortune of the Church that at this juncture, nearing the end of a virile and progressive century, the mightiest throne in Christendom should have fallen to a man whose love of the Church, and sincerity of purpose, were equaled by his imperfect morals, his personal pride, and his tactless will to power. He was not without charm: he loved learning, and rivaled Innocent III in legal training and wide culture; he founded the University of Rome, and restored and extended the Vatican Library; he gave commissions to Giotto and Arnolfo di Cambio, and helped finance the amazing façade of Orvieto Cathedral.

He had prepared his own elevation by persuading the saintly but incompetent Celestine V to resign after a pontificate of five months—an unprecedented act that surrounded Boniface with ill will from the start. To scotch all plans for a restoration, he ordered the eighty-year-old Celestine to be kept in detention in Rome; Celestine escaped, was captured, escaped again, wandered for weeks through Apulia, reached the Adriatic, attempted a crossing to Dalmatia, was wrecked, was cast ashore in Italy, and was brought before Boniface. He was condemned by the Pope to imprisonment in a narrow cell at Ferentino; and there, ten months later, he died (1296).95

The temper of the new Pope was sharpened by a succession of diplomatic defeats and costly victories. He tried to dissuade Frederick of Aragon from accepting the throne of Sicily; when Frederick persisted Boniface excommunicated him, and laid an interdict upon the island (1296). Neither King nor people paid any heed to these censures;96 and in the end Boniface recognized Frederick. To prepare for a crusade he ordered Venice and Genoa to sign a truce; they continued their war for three years more, and rejected his intervention in making peace. Failing to secure a favorable order in Florence, he placed the city under interdict, and invited Charles of Valois to enter and pacify Italy (1300). Charles accomplished nothing, but won the hatred of the Florentines for himself and the Pope. Seeking peace in his own Papal States, Boniface had attempted to settle a quarrel among the members of the powerful Colonna family; Pietro and Jacopo Colonna, both cardinals, repudiated his suggestions; he deposed and excommunicated them (1297); whereupon the rebellious nobles affixed to the doors of Roman churches, and laid upon the altar of St. Peter’s, a manifesto appealing from the Pope to a general council. Boniface repeated the excommunication, extended it to five other rebels, ordered their property confiscated, invaded the Colonna domain with papal troops, captured its fortresses, razed Palestrina to the ground, and had salt strewn over its ruins. The rebels surrendered, were forgiven, revolted again, were again beaten by the warrior Pope, fled from the Papal States, and planned revenge.

Amid these Italian tribulations Boniface was suddenly confronted by a major crisis in France. Philip IV, resolved to unify his realm, had seized the English province of Gascony; Edward I had declared war (1294); now, to finance their struggle, both kings decided to tax the property and personnel of the Church. The popes had permitted such taxation for crusades, but never for a purely secular war. The French clergy had recognized their duty of contributing to the defense of the state that protected their possessions, but they feared that if the power of the state to tax were unchecked, it would be a power to destroy. Philip had already reduced the role of the clergy in France; he had removed them from the manorial and royal courts, and from their old posts in the administration of the government and in the council of the king. Disturbed by this trend, the Cistercian Order refused to send Philip the fifth of their revenues which he had asked for the war with England, and its head addressed an appeal to the Pope. Boniface had to move carefully, for France had long been the chief support of the papacy in the struggle with Germany and the Empire; but he felt that the economic basis of the power and freedom of the Church would soon be lost if she could be shorn of her revenues by state taxation of Church property without papal consent. In February, 1296, he issued one of the most famous bulls in ecclesiastical history. Its first words, Clericis laicos, gave it a name, its first sentence made an unwise admission, and its tone recalled the papal bolts of Gregory VII:

Antiquity reports that laymen are exceedingly hostile to the clergy; and our experience certainly shows this to be true at present…. With the counsel of our brethren, and by our apostolic authority, we decree that if any clergy … shall pay to laymen… any part of their income or possessions … without the permission of the pope, they shall incur excommunication… And we also decree that all persons of whatever power or rank, who shall demand or receive such taxes, or shall seize or cause to be seized, the property of churches or of the clergy … shall incur excommunication.97

Philip for his part was convinced that the great wealth of the Church in France should share in the costs of the state. He countered the papal bull by prohibiting the export of gold, silver, precious stones, or food, and by forbidding foreign merchants or emissaries to remain in France. These measures blocked a main source of papal revenue, and banished from France the papal agents who were raising funds for a crusade in the East. In the bull Ineffabilis amor (September, 1296) Boniface retreated; he sanctioned voluntary contributions from the clergy for the necessary defense of the state, and conceded the right of the King to be the judge of such a necessity. Philip rescinded his retaliatory ordinances; he and Edward accepted Boniface—not as pope but as a private person—as arbitrator of their dispute; Boniface decided most of the issues in Philip’s favor; England yielded for the moment; and the three warriors enjoyed a passing peace.

Perhaps to replenish the papal treasury after the decline of receipts from England and France, perhaps to finance a war for the recovery of Sicily as a papal fief, and another war to extend the Papal States into Tuscany,98 Boniface proclaimed 1300 as a jubilee year. The plan was a complete success. Rome had never in its history seen such crowds before; now, apparently for the first time, traffic rules were enforced to govern the movement of the people.99 Boniface and his aides managed the affair well; food was brought in abundantly and was sold at moderate prices papally controlled. It was an advantage for the Pope that the great sums so collected were not earmarked for any special purpose, but could be used according to his judgment. Despite half victories and severe defeats, Boniface was now at the crest of his curve.

In the meantime, however, the Colonna exiles were entertaining Philip with tales of the Pope’s greed, injustice, and private heresies. A quarrel arose between Philip’s aides and a papal legate, Bernard Saisset; the legate was arrested on a charge of inciting to insurrection; he was tried by the royal court, convicted, and committed to the custody of the archbishop of Narbonne (1301). Boniface, shocked by this summary treatment of his legate, demanded Saisset’s immediate release, and instructed the French clergy to suspend payment of ecclesiastical revenues to the state. In the bull Ausculta fili (“Listen, son”; December, 1301) he appealed to Philip to listen modestly to the Vicar of Christ as the spiritual monarch over all the kings of the earth; he protested against the trial of a churchman before a civil court, and the continued use of ecclesiastical funds for secular purposes; and he announced that he would summon the bishops and abbots of France to take measures “for the preservation of the liberties of the Church, the reformation of the kingdom, and the amendment of the King.”100 When this bull was presented to Philip, the count of Artois snatched it from the hands of the Pope’s emissary and flung it into the fire; and a copy destined for publication by the French clergy was suppressed. Passion was inflamed on both sides by the circulation of two spurious documents, one allegedly from Boniface to Philip demanding obedience even in temporal affairs, the other from Philip to Boniface informing “thy very great fatuity that in temporal things we are subject to no one”; and these forgeries were widely accepted as genuine.101

On February 11, 1302, the bull Ausculta fili was officially burned at Paris before the King and a great multitude. To forestall the ecclesiastical council proposed by Boniface, Philip summoned the three estates of his realm to meet at Paris in April. At this first States-General in French history all three classes —nobles, clergy, and commons—wrote separately to Rome in defense of the King and his temporal power. Some forty-five French prelates, despite Philip’s prohibition, and the confiscation of their property, attended the council at Rome in October, 1302. From that council issued the bull Unam sanctam, which made arrestingly specific the claims of the papacy. There is, said the bull, but one true Church, outside of which there is no salvation; there is but one body of Christ, with one head, not two; that head is Christ and His representative, the Roman pope. There are two swords or powers—the spiritual and the temporal; the first is borne by the Church; the second is borne for the Church by the king, but under the will and sufferance of the priest. The spiritual power is above the temporal, and has the right to instruct it regarding its highest end, and to judge it when it does evil. “We declare and define and pronounce,” concluded the bull, “that it is necessary for salvation that all men should be subject to the Roman pontiff.”102

Philip replied by calling two assemblies (March and June, 1303), which drew up a formal indictment of Boniface as a tyrant, sorcerer, murderer, embezzler, adulterer, sodomite, simoniac, idolator, and infidel,103 and demanded his deposition by a general council of the Church. The King commissioned William of Nogaret, his chief legist, to go to Rome and notify the Pope of the King’s appeal to a general council. Boniface, then in the papal palace at Anagni, declared that only the pope could call a general council, and prepared a decree excommunicating Philip and laying an interdict upon France. Before he could issue it William of Nogaret and Sciarra Colonna, heading a band of 2000 mercenaries, burst into the palace, presented Philip’s message of notification, and demanded the Pope’s resignation (September 7, 1303). Boniface refused. A tradition “of considerable trustworthiness”104 says that Sciarra struck the Pontiff in the face, and would have killed him had not Nogaret intervened. Boniface was seventy-five years old, physically weak, but still defiant. For three days he was kept a prisoner in his palace, while the mercenaries plundered it. Then the people of Anagni, reinforced by 400 horsemen from the Orsini clan, scattered the mercenaries and freed the Pope. Apparently his jailers had given him no food in the three days; for standing in the market place he begged: “If there be any good woman who would give me an alms of wine and bread, I would bestow upon her God’s blessing and mine.” The Orsini led him to Rome and the Vatican. There he fell into a violent fever; and in a few days he died (October 11, 1303).

His successor, Benedict XI (1303–4), excommunicated Nogaret, Sciarra Colonna, and thirteen others whom he had seen breaking into the palace at Anagni. A month later Benedict died at Perugia, apparently poisoned by Italian Ghibellines.105 Philip agreed to support Bertrand de Got, Archbishop of Bordeaux, for the papacy if he would adopt a conciliatory policy, absolve those who had been excommunicated for the attack upon Boniface, allow an annual income tax of ten per cent to be levied upon the French clergy for five years, restore the Colonnas to their offices and property, and condemn the memory of Boniface.106 We do not know how far Bertrand consented. He was chosen Pope, and took the name of Clement V (1305). The cardinals warned him that his life would be unsafe in Rome; and after some hesitation, and perhaps a pointed suggestion from Philip, Clement removed the papal seat to Avignon, on the east bank of the Rhone just outside the southeastern boundary of France (1309). So began the sixty-eight years of the “Babylonian Captivity” of the popes. The papacy had freed itself from Germany, and surrendered to France.