Byzantine art, so generated, dedicated itself to expounding the doctrines of Christianity, and displaying the glory of the state. It recounted on vestments and tapestries, in mosaics and murals, the life of Christ, the sorrows of Mary, the career of the apostle or martyr whose bones were enshrined in the church. Or it entered the court, decorated the palace of the sovereign, covered his official robes with symbolic emblems or historical designs, dazzled his subjects with flamboyant pageantry, and ended by representing Christ and Mary as an emperor and a queen. The Byzantine artist had small choice of patron, and therefore of subject or style; monarch or patriarch told him what to do, and how. He worked in a group, and seldom left an individual name to history. He achieved miracles of brilliance, he exalted and humbled the people with the splendor of his creations; but his art paid in formalism, narrowness, and stagnation for serving an absolute monarch and a changeless creed.

He commanded abundant materials: marble quarries in the Proconnesus, Attica, Italy; spoliable columns and capitals wherever a pagan temple survived; and bricks almost growing in the sun-dried earth. Usually he worked with mortared brick; it lent itself well to the curved forms imposed upon him by Oriental styles. Often he contented himself with the cruciform plan—a basilica crossed with a transept and prolonged to an apse; sometimes he broke the basilica into an octagon, as in Sts. Sergius and Bacchus’ at Constantinople, or in San Vitale’s at Ravenna. But his distinctive skill, in which he surpassed all artists before him or since, lay in raising a circular dome over a polygonal frame. His favorite means to this end was the pendentive: i.e., he built an arch or semicircle of bricks over each side of the polygon, raised a spherical triangle of bricks upward and inward between each semicircle, and laid a dome upon the resultant circular ring. The spherical triangles were the pendentives, “hanging” from the rim of the dome to the top of the polygon. In architectural effect the circle was squared. Thereafter the basilican style almost disappeared from the East.

Within the edifice the Byzantine builder lavished all the skills of a dozen arts. He rarely used statuary; he sought not so much to represent figures of men and women as to create an abstract beauty of symbolic form. Even so the Byzantine sculptors were artisans of ability, patience, and resource. They carved the “Theodosian” capital by combining the “ears” of the Ionic with the leaves of the Corinthian order; and to make profusion more confounded, they cut into this composite capital a very jungle of animals and plants. Since the result was not too well adapted to sustain a wall or an arch, they inserted between these and the capital an impost or “pulvino,” square and broad at the top, round and narrower at the base; and then, in the course of time, they carved this too with flowers. Here again, as in the domed square, Persia conquered Greece.—But further, painters were assigned to adorn the walls with edifying or terrifying pictures; mosaicists laid their cubes of brightly colored stone or glass, in backgrounds of blue or gold, upon the floors or walls, or over the altar, or in the spandrels of the arches, or wherever an empty surface challenged the Oriental eye. Jewelers set gems into vestments, altars, columns, walls; metalworkers inserted gold or silver plates; woodworkers carved the pulpit or chancel rails; weavers hung tapestries, laid rugs, and covered altar and pulpit with embroidery and silk. Never before had an art been so rich in color, so subtle in symbolism, so exuberant in decoration, so well adapted to quiet the intellect and stir the soul.

3. St. Sophia

Not till Justinian did the Greek, Roman, Oriental, and Christian factors complete their fusion into Byzantine art. The Nika revolt gave him, like another Nero, an opportunity to rebuild his capital. In the ecstasy of a moment’s freedom the mob had burned down the Senate House, the Baths of Zeuxippus, the porticoes of the Augusteum, a wing of the imperial palace, and St. Sophia, cathedral of the patriarch. Justinian might have rebuilt these on their old plans, and within a year or two; instead he resolved to spend more time, money, and men, make his capital more beautiful than Rome, and raise a church that would outshine all other edifices on the earth. He began now one of the most ambitious building programs in history: fortresses, palaces, monasteries, churches, porticoes, and gates rose throughout the Empire. In Constantinople he rebuilt the Senate House in white marble, and the Baths of Zeuxippus in polychrome marble; raised a marble portico and promenade in the-Augusteum; and brought fresh water to the city in a new aqueduct that rivaled Italy’s best. He made his own palace the acme of splendor and luxury: its floors and walls were of marble; its ceilings recounted in mosaic brilliance the triumphs of his reign, and showed the senators “in festal mood, bestowing upon the Emperor honors almost divine.”36 And across the Bosporus, near Chalcedon, he built, as a summer residence for Theodora and her court, the palatial villa of Herion, equipped with its own harbor, forum, church, and baths.

Forty days after the Nika revolt had subsided, he began a new St. Sophia-dedicated not to any saint of that name, but to the Hagia Sophia, the Holy Wisdom, or Creative Logos, of God Himself. From Tralles in Asia Minor, and from Ionian Miletus, he summoned Anthemius and Isidore, the most famous of living architects, to plan and superintend the work. Abandoning the traditional basilican form, they conceived a design whose center would be a spacious dome resting not on walls but on massive piers, and buttressed by a half dome at either end. Ten thousand workmen were engaged, 320,000 pounds of gold ($134,000,000) were spent, on the enterprise, quite emptying the treasury. Provincial governors were directed to send to the new shrine the finest relics of ancient monuments; marbles of a dozen kinds and tints were imported from a dozen areas; gold, silver, ivory, and precious stones were poured into the decoration. Justinian himself shared busily in the design and the construction, and took no small part (his scornful adulator tells us) in solving technical problems. Dressed in white linen, with a staff in his hand and a kerchief on his head, he haunted the operation day after day, encouraging the workers to complete their tasks competently and on time. In five years and ten months the edifice was complete; and on December 26, 537, the Emperor and the Patriarch Menas led a solemn inaugural procession to the resplendent cathedral. Justinian walked alone to the pulpit, and lifting up his hands, cried out: “Glory be to God who has thought me worthy to accomplish so great a work! O Solomon! I have vanquished you!”

The ground plan was a Greek cross 250 by 225 feet; each end of the cross was covered by a minor dome; the central dome rose over the square (100 by 100 feet) formed by the intersecting arms; the apex of the dome was 180 feet above the ground; its diameter was 100 feet—32 less than the dome of the Pantheon in Rome. The latter had been poured in concrete in one solid piece; St. Sophia’s dome was made of brick in thirty converging panels—a much weaker construction.* The distinction of this dome was not in size but in support: it rested not on a circular structure, as in the Pantheon, but on pendentives and arches that mediated between the circular rim and the square base; never has this architectural problem been more satisfactorily solved. Procopius described the dome as “a work admirable and terrifying … seeming not to rest on the masonry below it, but to be suspended by a chain of gold from the height of the sky.”37

The interior was a panorama of luminous decoration. Marble of many colors—white, green, red, yellow, purple, gold—made the pavement, walls, and two-storied colonnades look like a field of flowers. Delicate stone carvings covered capitals, arches, spandrels, moldings, and cornices with classic leaves of acanthus and vine. Mosaics of unprecedented scope and splendor looked down from walls and vaults. Forty silver chandeliers, hanging from the rim of the dome, helped as many windows to illuminate the church. The sense of spaciousness left by the long nave and aisles, and by the pillarless space under the central dome; the metal lacework of the silver railing before the apse, and of the iron railing in the upper gallery; the pulpit inset with ivory, silver, and precious stones; the solid silver throne of the patriarch; the silk-and-gold curtain that rose over the altar with figures of the Emperor and the Empress receiving the benedictions of Christ and Mary; the golden altar itself, of rare marbles, and bearing sacred vessels of silver and gold: this lavish ornamentation might have warranted Justinian in anticipating the boast of the Mogul shahs—that they built like giants and finished like jewelers.

St. Sophia was at once the inauguration and the culmination of the Byzantine style. Men everywhere spoke of it as “the Great Church,” and even the skeptical Procopius wrote of it with awe. “When one enters this building to pray, he feels that it is not the work of human power. … The soul, lifting itself to the sky, realizes that here God is close by, and that He takes delight in this, His chosen home.”†38

4. From Constantinople to Ravenna

St. Sophia was Justinian’s supreme achievement, more lasting than his conquests or his laws. But Procopius describes twenty-four other churches built or rebuilt by him in the capital, and remarks: “If you should see one of them by itself you would suppose that the Emperor had built this work only, and had spent the whole time of his reign on this one alone.”39 Throughout the Empire this fury of construction raged till Justinian’s death; and that sixth century which marked the beginning of the Dark Ages in the West was in the East one of the richest epochs in architectural history. In Ephesus, Antioch, Gaza, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Salonika, Ravenna, Rome, and from Crimean Kerch to African Sfax, a thousand churches celebrated the triumph both of Christianity over paganism and of the Oriental-Byzantine over the Greco-Roman style. External columns, architraves, pediments; and friezes made way for the vault, the pendentive, and the dome. Syria had a veritable renaissance in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries; her schools at Antioch, Berytus (Beirut), Edessa, and Nisibis poured forth orators, lawyers, historians, and heretics; her artisans excelled in mosaics, textiles, and all decorative arts; her architects raised a hundred churches; her sculptors adorned them with lavish reliefs.

Alexandria was the one city in the Empire that never ceased to prosper. Her founder had chosen for her a site that almost forced the Mediterranean world to use her ports and enhance her trade. None of her ancient or early medieval architecture has survived; but the scattered relics of her work in metal, ivory, wood, and portraiture suggest a people as rich in art as in sensuality and bigotry. Coptic architecture, which had begun with the Roman basilica, became under Justinian predominantly Oriental.

The architectural splendor of Ravenna began soon after Honorius made it the seat of the Western Empire in 404. The city prospered in the long regency of Galla Placidia; and the close relations maintained with Constantinople brought Eastern artists and styles to mingle with Italian architects and forms. The typical Oriental plan of a dome placed with pendentives over the transept of a cruciform base appeared there as early as 450 in the Mausoleum where Placidia at last found tranquillity; within it one may still see the famous mosaic of Christ as the Good Shepherd. In 458 Bishop Neon added to the domed baptistery of the Basilica Ursiana a series of mosaics that included remarkably individual portraits of the Apostles. About 500 Theodoric built for his Arian bishop a cathedral named after St. Apollinaris, the reputed founder of the Christian community in Ravenna; here, in world-renowned mosaics, the white-robed saints bear themselves with a stiff solemnity that already suggests the Byzantine style.

The conquest of Ravenna by Belisarius advanced the victory of Byzantine art in Italy. The church of San Vitale was completed (547) under Justinian and Theodora, who financed its decoration, and lent their unseductive features to its adornment. There is every indication that these mosaics are realistic portraits; and emperor and empress must be credited with courage in permitting their likenesses to be transmitted to posterity. The attitudes of these rulers, ecclesiastics, and eunuchs are hard and angular; their stiff frontality is a reversion to preclassical forms; the robes of the women are a mosaic triumph, but we miss here the happy grace of the Parthenon procession, or the Ara pacis of Augustus, or the nobility and tenderness of the figures on the portals of Chartres or Reims.

Two years after dedicating San Vitale the Bishop of Ravenna consecrated Sant’ Apollinare in Classe—a second church for the city’s patron saint, placed in the maritime suburb that had once been the Adriatic base of the Roman fleet (classis). Here is the old Roman basilican plan; but on the composite capitals a Byzantine touch appears in the acanthus leaves unclassically curled and twisted, as if blown by some Eastern wind. The long rows of perfect columns, the colorful (seventh-century) mosaics in the archivolts and spandrels of the colonnades, the lovely stucco plaques in the choir, the cross of gems on a bed of mosaic stars in the apse, make this one of the outstanding shrines of a peninsula that is almost a gallery of art.

5. The Byzantine Arts

Architecture was the masterpiece of the Byzantine artist, but about it or within it were a dozen other arts in which he achieved some memorable excellence. He did not care for sculpture in the round; the mood of the age preferred color to line; yet Procopius lauded the sculptors of his time—presumably the carvers of reliefs—as the equals of Pheidias and Praxiteles; and some stone sarcophagi of the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries have human figures chiseled with almost Hellenic grace, confused with an Asiatic plethora of ornament. The carving of ivory was a favorite art among the Byzantines; they used it for diptychs, triptychs, book covers, caskets, perfume boxes, statuettes, inlays, and in a hundred decorative ways; in this craft Hellenistic techniques survived unimpaired, and merely turned gods and heroes into Christ and the saints. The ivory chair of Bishop Maximian in the Basilica Ursiana at Ravenna (c. 550) is a major achievement in a minor art.

While the Far East, in the sixth century, was experimenting with oil colors,40 Byzantine painting adhered to traditional Greek methods: encaustic—colors burnt into panels of wood, canvas, or linen; fresco—colors mixed with lime and applied to wet plaster surfaces; and tempera—colors mixed with size or gum or glue and white of egg, and applied to panels or to plaster already dry. The Byzantine painter knew how to represent distance and depth, but usually shirked the difficulties of perspective by filling in the background with buildings and screens. Portraits were numerous, but few have survived. Church walls were decorated with murals; the fragments that remain show a rough realism, unshapely hands, stunted figures, sallow faces, and incredible coiffures.

The Byzantine artist excelled and reveled in the minute; his extant masterpieces of painting are not murals or panels, but the miniatures with which he literally “illuminated”—made bright with color—the publications of his age.* Books, being costly, were adorned like other precious objects. The miniaturist first sketched his design upon papyrus, parchment, or vellum with a fine brush or pen; laid down a background usually in gold or blue; filled in his colors, and decorated background and borders with graceful and delicate forms. At first he had merely elaborated the initial letter of a chapter or a page; sometimes he essayed a portrait of the author; then he illustrated the text with pictures; finally, as his art improved, he almost forgot the text, and spread himself out in luxurious ornament, taking a geometrical or floral motive, or a religious symbol, and repeating it in a maze of variations, until all the page was a glory of color and line, and the text seemed like an intrusion from a coarser world.

The illumination of manuscripts had been practiced in Pharaonic and Ptolemaic Egypt, and had passed thence to Hellenistic Greece and Rome. The Vatican treasures an Aeneid, the Ambrosian Library at Milan an Iliad, both ascribed to the fourth century, and completely classic in ornament. The transition from pagan to Christian miniatures appears in the Topographia Christiana of Cosmas Indicopleustes (c. 547), who earned his sobriquet by sailing to India, and his fame by trying to prove that the earth is flat. The oldest extant religious miniature is a fifth-century Genesis, now in the Library of Vienna; the text is written in gold and silver letters on twenty-four leaves of purple vellum; the forty-eight miniatures, in white, green, violet, red, and black, picture the story of man from Adam’s fall to Jacob’s death. Quite as beautiful are the Joshua Rotulus (Little Roll of the Book of Joshua) in the Vatican, and the Book of the Gospels illuminated by the monk Rabula in Mesopotamia in 586. From Mesopotamia and Syria came the figures and symbols that dominated the iconography, or picture-writing, of the Byzantine world; repeated in a thousand forms in the minor arts, they became stereotyped and conventional, and shared in producing the deadly immutability of Byzantine art.

Loving brilliance and permanence, the Byzantine painter made mosaic his favorite medium. For floors he chose tesserae of colored marble, as Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans had done; for other surfaces he used cubes of glass or enamel in every shade, cut in various sizes, but usually an eighth of an inch square. Precious stones were sometimes mingled with the cubes. Mosaic was often employed in making portable pictures or icons, to be set up in churches or homes, or carried on travels as aids to devotion and safety; preferably, however, the mosaicist sought the larger scope of church or palace walls. In his studio, upon a canvas bearing a colored design, he tentatively laid his cubes; and here his art was strained to produce immediately under his hand the precise gradation and melting of colors to be felt by other eyes from greater distances. Meanwhile a coat of heavy cement, and then a coat of fine cement, were laid upon the surface to be covered; into this matrix the mosaicist, following his canvas model, pressed his cubes, usually with cut edges to the front to catch the light. Curved surfaces like domes, and the conches or shell-like half domes of apses, were favored, since they would catch at different times and angles a variety of softened and shaded light. From this painstaking art Gothic would derive part of its inspiration for stained glass.

Such glass is mentioned in fifth-century texts, but no example remains, and apparently the stain was external, not fused.41 Glass-cutting and blowing were now a thousand years old, and Syria, their earliest known home, was still a center of the crafts. The art of engraving precious metals or stones had deteriorated since Aurelius; Byzantine gems, coins, and seals are of relatively poor design and workmanship. Jewelers nevertheless sold their products to nearly every class, for ornament was the soul of Byzantium. Goldsmith and silversmith studios were numerous in the capital; gold pyxes, chalices, and reliquaries adorned many altars; and silver plate oppressed the tables of moneyed homes.

Every house, almost every person, carried some textile finery. Egypt led the way here with its delicate, many-colored, figured fabrics—garments, curtains, hangings, and coverings; the Copts were the masters in these fields. Certain Egyptian tapestries of this period are almost identical in technique with the Gobelins.42 Byzantine weavers made silk brocades, embroideries, even embroidered shrouds—linens realistically painted with the features of the dead. In Constantinople a man was known by the garments he wore; each class prized and defended some distinctive refinement of dress; and a Byzantine assemblage doubtless shone like a peacock’s tail.

Among all classes music was popular. It played a rising role in the liturgy of the Church, and helped to fuse emotion into belief. In the fourth century Alypius wrote a Musical Introduction, whose extant portions are our chief guide to the musical notation of the Greeks. This representation of notes by letters was replaced, in that century, by abstract signs, neumes; Ambrose apparently introduced these to Milan, Hilary to Gaul, Jerome to Rome. About the end of the fifth century Romanus, a Greek monk, composed the words and music of hymns that still form part of the Greek liturgy, and have never been equaled in depth of feeling and power of expression. Boethius wrote an essay De Musica, summarizing the theories of Pythagoras, Aristoxenus, and Ptolemy; this little treatise was used as a text in music at Oxford and Cambridge until our times.43

One must be an Oriental to understand an Oriental art. To a Western mind the essence of Byzantinism means that the East had become supreme in the heart and head of Greece: in the autocratic government, the hierarchical stability of classes, the stagnation of science and philosophy, the state-dominated Church, the religion-dominated people, the gorgeous vestments and stately ceremonies, the sonorous and scenic ritual, the hypnotic chant of repetitious music, the overwhelming of the senses with brilliance and color, the conquest of naturalism by imagination, the submergence of representative under decorative art. The ancient Greek spirit would have found this alien and unbearable, but Greece herself was now part of the Orient. An Asiatic lassitude fell upon the Greek world precisely when it was to be challenged in its very life by the renewed vitality of Persia and the incredible energy of Islam.

CHAPTER VII

The Persians

224–641

I. SASANIAN SOCIETY

BEYOND the Euphrates or the Tigris, through all the history of Greece and Rome, lay that almost secret empire which for a thousand years had stood off expanding Europe and Asiatic hordes, never forgetting its Achaemenid glory, slowly recuperating from its Parthian wars, and so proudly maintaining its unique and aristocratic culture under its virile Sasanian monarchs, that it would transform the Islamic conquest of Iran into a Persian Renaissance.

Iran meant more, in our third century, than Iran or Persia today. It was by its very name the land of the “Aryans,” and included Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Sogdiana, and Balkh, as well as Iraq. “Persia,” anciently the name of the modern province of Fars, was but a southeastern fraction of this empire; but the Greeks and Romans, careless about “barbarians,” gave the name of a part to the whole. Through the center of Iran, from Himalayan southeast to Caucasian northwest, ran a mountainous dividing barrier; to the east was an arid lofty plateau; to the west lay the green valleys of the twin rivers, whose periodic overflow ran into a labyrinth of canals, and made Western Persia rich in wheat and dates, vines, and fruits. Between or along the rivers, or hiding in the hills, or hugging desert oases, were a myriad villages, a thousand towns, a hundred cities: Ecbatana, Rai, Mosul, Istakhr (once Persepolis), Susa, Seleucia, and magnificent Ctesiphon, seat of the Sasanian kings.

Ammianus describes the Persians of this period as “almost all slender, somewhat dark … with not uncomely beards, and long, shaggy hair.”1 The upper classes were not shaggy, nor always slender, often handsome, proud of bearing, and of an easy grace, with a flair for dangerous sports and splendid dress. Men covered their heads with turbans, their legs with baggy trousers, their feet with sandals or laced boots; the rich wore coats or tunics of wool and silk, and girt themselves with belt and sword; the poor resigned themselves to garments of cotton, hair, or skins. The women dressed in boots and breeches, loose shirts and cloaks and flowing robes; curled their black hair into a coil in front, let it hang behind, and brightened it with flowers. All classes loved color and ornament. Priests and zealous Zoroastrians affected white cotton clothing as a symbol of purity; generals preferred red; kings distinguished themselves with red shoes, blue trousers, and a headdress topped with an inflated ball or the head of a beast or a bird. In Persia, as in all civilized societies, clothes made half the man, and slightly more of the woman.

The typical educated Persian was Gallicanly impulsive, enthusiastic, and mercurial; often indolent, but quickly alert; given to “mad and extravagant talk … rather crafty than courageous, and to be feared only at long range”2—which was where they kept their enemies. The poor drank beer, but nearly all classes, including the gods, preferred wine; the pious and thrifty Persians poured it out in religious ritual, waited a reasonable time for the gods to come and drink, then drank the sacred beverage themselves.3 Persian manners, in this Sasanian period, are described as coarser than in the Achaemenid, more refined than in the Parthian;4 but the narratives of Procopius leave us with the impression that the Persians continued to be better gentlemen than the Greeks.5 The ceremonies and diplomatic forms of the Persian court were in large measure adopted by the Greek emperors; the rival sovereigns addressed each other as “brother,” provided immunity and safe-conducts for foreign diplomats, and exempted them from customs searches and dues.6 The conventions of European and American diplomacy may be traced to the courts of the Persian kings.

“Most Persians,” Ammianus reported, “are extravagantly given to venery,”7 but he confesses that pederasty and prostitution were less frequent among them than among the Greeks. Rabbi Gamaliel praised the Persians for three qualities: “They are temperate in eating, modest in the privy and in marital relations.”8 Every influence was used to stimulate marriage and the birth rate, in order that man power should suffice in war; in this aspect Mars, not Venus, is the god of love. Religion enjoined marriage, celebrated it with awesome rites, and taught that fertility strengthened Ormuzd, the god of light, in his cosmic conflict with Ahriman, the Satan of the Zoroastrian creed.9 The head of the household practiced ancestor worship at the family hearth, and sought offspring to ensure his own later cult and care; if no son was born to him he adopted one. Parents generally arranged the marriage of their children, often with the aid of a professional matrimonial agent; but a woman might marry against the wishes of her parents. Dowries and marriage settlements financed early marriage and parentage. Polygamy was allowed, and was recommended where the first wife proved barren. Adultery flourished.10 The husband might divorce his wife for infidelity, the wife might divorce her husband for desertion and cruelty. Concubines were permitted. Like the ancient Greek hetairai, these concubines were free to move about in public, and to attend the banquets of the men;11 but legal wives were usually kept in private apartments in the home;12 this old Persian custom was bequeathed to Islam. Persian women were exceptionally beautiful, and perhaps men had to be guarded from them. In the Shahnama of Firdausi it is the women who yearn and take the initiative in courtship and seduction. Feminine charms overcame masculine laws.

Children were reared with the help of religious belief, which seems indispensable to parental authority. They amused themselves with ball games, athletics, and chess,13 and at an early age joined in their elders’ pastimes-archery, horse racing, polo, and the hunt. Every Sasanian found music necessary to the operations of religion, love, and war; “music and the songs of beautiful women,” said Firdausi, “accompanied the scene” at royal banquets and receptions;14 lyre, guitar, flute, pipe, horn, drum, and other instruments abounded; tradition avers that Khosru Parvez’ favorite singer, Barbad, composed 360 songs, and sang them to his royal patron, one each night for a year.15 In education, too, religion played a major part; primary schools were situated on temple grounds, and were taught by priests. Higher education in literature, medicine, science, and philosophy was provided in the celebrated academy at Jund-i-Shapur in Susiana. The sons of feudal chiefs and provincial satraps often lived near the king, and were instructed with the princes of the royal family in a college attached to the court.16

Pahlavi, the Indo-European language of Parthian Persia, continued in use. Of its literature in this age only some 600,000 words survive, nearly all dealing with religion. We know that it was extensive;17 but as the priests were its guardians and transmitters, they allowed most of the secular material to perish. (A like process may have deluded us as to the overwhelmingly religious character of early medieval literature in Christendom.) The Sasanian kings were enlightened patrons of letters and philosophy—Khosru Anushirvan above all: he had Plato and Aristotle translated into Pahlavi, had them taught at Jund-i-Shapur, and even read them himself. During his reign many historical annals were compiled, of which the sole survivor is the Karnamaki-Artakhshatr, or Deeds of Ardashir, a mixture of history and romance that served Firdausi as the basis of his Shahnama. When Justinian closed the schools of Athens seven of their professors fled to Persia and found refuge at Khosru’s court. In time they grew homesick; and in his treaty of 533 with Justinian, the “barbarian” king stipulated that the Greek sages should be allowed to return, and be free from persecution.

Under this enlightened monarch the college of Jund-i-Shapur, which had been founded in the fourth or fifth century, became “the greatest intellectual center of the time.”18 Students and teachers came to it from every quarter of the world. Nestorian Christians were received there, and brought Syriac translations of Greek works in medicine and philosophy. Neoplatonists there planted the seeds of Sufi mysticism; there the medical lore of India, Persia, Syria, and Greece mingled to produce a flourishing school of therapy.19 In Persian theory disease resulted from contamination and impurity of one or more of the four elements—fire, water, earth, and air; public health, said Persian physicians and priests, required the burning of all putrefying matter, and individual health demanded strict obedience to the Zoroastrian code of cleanliness.20

Of Persian astronomy in this period we only know that it maintained an orderly calendar, divided the year into twelve months of thirty days, each month into two seven-day and two eight-day weeks, and added five intercalary days at the end of the year.21 Astrology and magic were universal; no important step was taken without reference to the status of the constellations; and every earthly career, men believed, was determined by the good and evil stars that fought in the sky—as angels and demons fought in the human soul—the ancient war of Ormuzd and Ahriman.

The Zoroastrian religion was restored to authority and affluence by the Sasanian dynasty; lands and tithes were assigned to the priests; government was founded on religion, as in Europe. An archimagus, second only to the king in power, headed an omnipresent hereditary priestly caste of Magi, who controlled nearly all the intellectual life of Persia, frightened sinners and rebels with threats of hell, and kept the Persian mind and masses in bondage for four centuries.22 Now and then they protected the citizen against the taxgatherer, and the poor against oppression.23 The Magian organization was so rich that kings sometimes borrowed great sums from the temple treasuries. Every important town had a fire temple, in which a sacred flame, supposedly inextinguishable, symbolized the god of light. Only a life of virtue and ritual cleanliness could save the soul from Ahriman; in the battle against that devil it was vital to have the aid of the Magi and their magic—thai divinations, incantations, sorceries, and prayers. So helped, the soul would attain holiness and purity, pass the awful assize of the Last Judgment, and enjoy everlasting happiness in paradise.

Around this official faith other religions found modest room. Mithras, the sun god so popular with the Parthians, received a minor worship as chief helper of Ormuzd. But the Zoroastrian priests, like the Christians, Moslems, and Jews, made persistent apostasy from the national creed a capital crime. When Mani (c. 216–76), claiming to be a fourth divine messenger in the line of Buddha, Zoroaster, and Jesus, announced a religion of celibacy, pacifism, and quietism, the militant and nationalistic Magi had him crucified; and Manicheism had to seek its main success abroad. To Judaism and Christianity, however, the Sasanian priests and kings were generally tolerant, much as the popes were more lenient with Jews than with heretics. A large number of Jews found asylum in the western provinces of the Persian Empire. Christianity was already established there when the Sasanians came to power; it was tolerated until it became the official faith of Persia’s immemorial enemies, Greece and Rome; it was persecuted after its clergy, as at Nisibis in 338, took an active part in the defense of Byzantine territory against Shapur II,24 and the Christians in Persia revealed their natural hopes for a Byzantine victory.25 In 341 Shapur ordered the massacre of all Christians in his Empire; entire villages of Christians were being slaughtered when he restricted the proscription to priests, monks, and nuns; even so 16,000 Christians died in a persecution that lasted till Shapur’s death (379). Yezdegird I (399–420) restored religious freedom to the Christians, and helped them rebuild their churches. In 422 a council of Persian bishops made the Persian Christian Church independent of both Greek and Roman Christianity.

Within the framework of religious worship and dispute, governmental edicts and crises, civil and foreign wars, the people impatiently provided the sinews of state and church, tilling the soil, pasturing flocks, practicing handicrafts, arguing trade. Agriculture was made a religious duty: to clear the wilderness, cultivate the earth, eradicate pests and weeds, reclaim waste lands, harness the streams to irrigate the land—these heroic labors, the people were told, ensured the final victory of Ormuzd over Ahriman. Much spiritual solace was needed by the Persian peasant, for usually he toiled as tenant for a feudal lord, and paid from a sixth to a third of his crops in taxes and dues. About 540 the Persians took from India the art of making sugar from the cane; the Greek Emperor Heraclius found a treasury of sugar in the royal palace at Ctesiphon (627); the Arabs, conquering Persia fourteen years later, soon learned to cultivate the plant, and introduced it into Egypt, Sicily, Morocco, and Spain, whence it spread through Europe.26 Animal husbandry was a Persian forte; Persian horses were second only to Arab steeds in pedigree, spirit, beauty, and speed; every Persian loved a horse as Rustam loved Rakush. The dog was so useful in guarding flocks and homes that the Persians made him a sacred animal; and the Persian cat acquired distinction universally.

Persian industry under the Sasanians developed from domestic to urban forms. Guilds were numerous, and some towns had a revolutionary proletariat.27 Silk weaving was introduced from China; Sasanian silks were sought for everywhere, and served as models for the textile art in Byzantium, China, and Japan. Chinese merchants came to Iran to sell raw silk and buy rugs, jewels, rouge; Armenians, Syrians, and Jews connected Persia, Byzantium, and Rome in slow exchange. Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled state post and merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all provinces; and harbors were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India. Governmental regulations limited the price of corn, medicines, and other necessaries, and prevented “corners” and monopolies.28 We may judge the wealth of the upper classes by the story of the baron who, having invited a thousand guests to dinner, and finding that he had only 500 dinner services, was able to borrow 500 more from his neighbors.29

The feudal lords, living chiefly on their rural estates, organized the exploitation of land and men, and raised regiments from their tenantry to fight the nation’s wars. They trained themselves to battle by following the chase with passion and bravery; they served as gallant cavalry officers, man and animal armored as in later feudal Europe; but they fell short of the Romans in disciplining their troops, or in applying the latest engineering arts of siege and defense. Above them in social caste were the great aristocrats who ruled the provinces as satraps, or headed departments of the government. Administration must have been reasonably competent, for though taxation was less severe than in the Roman Empire of East or West, the Persian treasury was often richer than that of the emperors. Khosru Parvez had $460,000,000 in his coffers in 626, and an annual income of $170,000,00030—enormous sums in terms of the purchasing power of medieval silver and gold.

Law was created by the kings, their councilors, and the Magi, on the basis of the old Avestan code; its interpretation and administration were left to the priests. Ammianus, who fought the Persians, reckoned their judges as “upright men of proved experience and legal learning.”31 In general, Persians were known as men of their word. Oaths in court were surrounded with all the aura of religion; violated oaths were punished severely in law, and in hell by an endless shower of arrows, axes, and stones. Ordeals were used to detect guilt: suspects were invited to walk over red-hot substances, or go through fire, or eat poisoned food. Infanticide and abortion were forbidden with heavy penalties; pederasty was punished with death; the detected adulterer was banished; the adulteress lost her nose and ears. Appeal could be made to higher courts, and sentences of death could be carried out only after review and approval by the king.

The king attributed his power to the gods, presented himself as their vicegerent, and emulated their superiority to their own decrees. He called himself, when time permitted, “King of Kings, King of the Aryans and the non-Aryans, Sovereign of the Universe, Descendant of the Gods”;32 Shapur II added “Brother of the Sun and Moon, Companion of the Stars.” Theoretically absolute, the Sasanian monarch usually acted with the advice of his ministers, who composed a council of state. Masudi, the Moslem historian, praised the “excellent administration of the” Sasanian “kings, their wellordered policy, their care for their subjects, and the prosperity of their domains.”33 Said Khosru Anushirvan, according to Ibn Khaldun: “Without army, no king; without revenues, no army; without taxes, no revenue; without agriculture, no taxes; without just government, no agriculture.”34 In normal times the monarchical office was hereditary, but might be transmitted by the king to a younger son; in two instances the supreme power was held by queens. When no direct heir was available, the nobles and prelates chose a ruler, but their choice was restricted to members of the royal family.

The life of the king was an exhausting round of obligations. He was expected to take fearlessly to the hunt; he moved to it in a brocaded pavilion drawn by ten camels royally dressed; seven camels carried his throne, one hundred bore his minstrels. Ten thousand knights might accompany him; but if we may credit the Sasanian rock reliefs he had at last to mount a horse, face in the first person a stag, ibex, antelope, buffalo, tiger, lion, or some other of the animals gathered in the king’s park or “paradise.” Back in his palace, he confronted the chores of government amid a thousand attendants and in a maze of officious ceremony. He had to dress himself in robes heavy with jewelry, seat himself on a golden throne, and wear a crown so burdensome that it had to be suspended an invisible distance from his immovable head. So he received ambassadors and guests, observed a thousand punctilios of protocol, passed judgment, received appointments and reports. Those who approached him prostrated themselves, kissed the ground, rose only at his bidding, and spoke to him through a handkerchief held to their mouths, lest their breath infect or profane the king. At night he retired to one of his wives or concubines, and eugenically disseminated his superior seed.

II. SASANIAN ROYALTY

Sasan, in Persian tradition, was a priest of Persepolis; his son Papak was a petty prince of Khur; Papak killed Gozihr, ruler of the province of Persis, made himself king of the province, and bequeathed his power to his son Shapur; Shapur died of a timely accident, and was succeeded by his brother Ardashir. Artabanus V, last of the Arsacid or Parthian kings of Persia, refused to recognize this new local dynasty; Ardashir overthrew Artabanus in battle (224), and became King of Kings (226). He replaced the loose feudal rule of the Arsacids with a strong royal power governing through a centralized but spreading bureaucracy; won the support of the priestly caste by restoring the Zoroastrian hierarchy and faith; and roused the pride of the people by announcing that he would destroy Hellenistic influence in Persia, avenge Darius II against the heirs of Alexander, and reconquer all the territory once held by the Achaemenid kings. He almost kept his word. His swift campaigns extended the boundaries of Persia to the Oxus in the northeast, and to the Euphrates in the west. Dying (241), he placed the crown on the head of his son Shapur, and bade him drive the Greeks and Romans into the sea.

FIG. 1—Interior of Santa Maria Maggiore

Rome

FIG. 2—Interior of Hagia Sophia

Constantinople

FIG. 3—Interior of San Vitale

Ravenna

FIG. 4—Detail of Rock Relief

Taq-I-Bustan

Courtesy of Asia Institute

FIG. 5—Court of the Great Mosque

Damascus

Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

FIG. 6—Dome of the Rock

Jerusalem

FIG. 7—Portion of Stone Relief

Mshatta, Syria

FIG. 8—Court of El Azhar Mosque

Cairo

FIG. 9—Wood Minbar in El Agsa Mosque

Jerusalem

FIG. 10—Pavilion on Court of Lions, the AIhambra

Granada

FIG. 11—Interior of Mosque

Cordova

FIG. 12—Façade of St. Mark’s

Venice

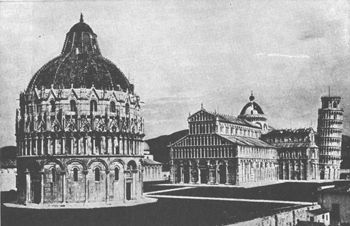

FIG. 13—Piazza of the Duomo, Showing Baptistry, Cathedral, and Learning Tower

Pisa

FIG. 14—Interior of Capella Palatina

Palermo

FIG. 15—Apse of Cathedral

Monreale

Shapur or Sapor I (241–72) inherited all the vigor and craft of his father. The rock reliefs represent him as a man of handsome and noble features; but these reliefs were doubtless stylized compliments. He received a good education, and loved learning; he was so charmed by the conversation of the Sophist Eustathius, the Greek ambassador, that he thought of resigning his throne and becoming a philosopher.35 Unlike his later namesake, he gave full freedom to all religions, allowed Mani to preach at his court, and declared that “Magi, Manicheans, Jews, Christians, and all men of whatever religion should be left undisturbed” in his Empire.36 Continuing Ardashir’s redaction of the Avesta, he persuaded the priests to include in this Persian Bible secular works on metaphysics, astronomy, and medicine, mostly borrowed from India and Greece. He was a liberal patron of the arts. He was not as great a general as Shapur II or the two Khosrus, but he was the ablest administrator in the long Sasanian line. He built a new capital at Shapur, whose ruins still bear his name; and at Shushtar, on the Karun River, he raised one of the major engineering works of antiquity—a dam of granite blocks, forming a bridge 1710 feet long and 20 feet wide; the course of the stream was temporarily changed to allow the construction; its bed was solidly paved; and great sluice gates regulated the flow. Tradition says that Shapur used Roman engineers and prisoners to design and build this dam, which continued to function to our own century.37 Turning reluctantly to war, Shapur invaded Syria, reached Antioch, was defeated by a Roman army, and made a peace (244) that restored to Rome all that he had taken. Resenting Armenia’s co-operation with Rome, he entered that country and established there a dynasty friendly to Persia (252). His right flank so protected, he resumed the war with Rome, defeated and captured the Emperor Valerian (260), sacked Antioch, and took thousands of prisoners to forced labor in Iran. Odenathus, governor of Palmyra, joined forces with Rome, and compelled Shapur again to resign himself to the Euphrates as the Roman-Persian frontier.

His successors, from 272 to 302, were royal mediocrities. History makes short shrift of Hormizd II (302–9), for he maintained prosperity and peace. He went about repairing public buildings and private dwellings, especially those of the poor, all at state expense. He established a new court of justice devoted to hearing the complaints of the poor against the rich, and often presided himself. We do not know if these strange habits precluded his son from inheriting the throne; in any case, when Hormizd died, the nobles imprisoned his son, and gave the throne to his unborn child, whom they confidently hailed as Shapur II; and to make matters clear they crowned the foetus by suspending the royal diadem over the mother’s womb.38

With this good start Shapur II entered upon the longest reign in Asiatic history (309–79). From childhood he was trained for war; he hardened his body and will, and at sixteen took the government and the field. Invading eastern Arabia, he laid waste a score of villages, killed thousands of captives, and led others into bondage by cords attached to their wounds. In 337 he renewed the war with Rome for mastery of the trade routes to the Far East, and continued it, with pacific intervals, almost till his death. The conversion of Rome and Armenia to Christianity gave the old struggle a new intensity, as if the gods in Homeric frenzy had joined the fray. Through forty years Shapur fought a long line of Roman emperors. Julian drove him back to Ctesiphon, but retreated ingloriously; Jovian, outmaneuvered, was forced to a peace (363) that yielded to Shapur the Roman provinces on the Tigris, and all Armenia. When Shapur II died Persia was at the height of its power and prestige, and a hundred thousand acres had been improved with human blood.

In the next century war moved to the eastern frontier. About 425 a Turanian people known to the Greeks as Ephthalites, and mistakenly called “White Huns,” captured the region between the Oxus and the Jaxartes. The Sasanian King Bahram V (420–38), named Gur—“the wild ass”—because of his reckless hunting feats, fought them successfully; but after his death they spread through fertility and war, and built an empire extending from the Caspian to the Indus, with its capital at Gurgan and its chief city at Balkh. They overcame and slew King Firuz (459–84), and forced King Balas (484–8) to pay them tribute.

So threatened in the east, Persia was at the same time thrown into chaos by the struggle of the monarchy to maintain its authority against the nobles and the priests. Kavadh I (488–531) thought to weaken these enemies by encouraging a communist movement which had made them the chief object of its attack. About 490 Mazdak, a Zoroastrian priest, had proclaimed himself God-sent to preach an old creed: that all men are born equal, that no one has any natural right to possess more than another, that property and marriage are human inventions and miserable mistakes, and that all goods and all women should be the common property of all men. His enemies claimed that he condoned theft, adultery, and incest as natural protests against property and marriage, and as legitimate approximations to utopia. The poor and some others heard him gladly, but Mazdak was probably surprised to receive the approval of a king. His followers began to plunder not only the homes but the harems of the rich, and to carry off for their own uses the most illustrious and costly concubines. The outraged nobles imprisoned Kavadh, and set his brother Djamasp upon the throne. After three years in the “Castle of Oblivion” Kavadh escaped, and fled to the Ephthalites. Eager to have a dependent as the ruler of Persia, they provided him with an army, and helped him to take Ctesiphon. Djamasp abdicated, the nobles fled to their estates, and Kavadh was again King of Kings (499). Having made his power secure, he turned upon the communists, and put Mazdak and thousands of his followers to death.39 Perhaps the movement had raised the status of labor, for the decrees of the council of state were henceforth signed not only by princes and prelates, but also by the heads of the major guilds.40 Kavadh ruled for another generation; fought with success against his friends the Ephthalites, inconclusively with Rome; and dying, left the throne to his second son Khosru, the greatest of Sasanian kings.

Khosru I (“Fair Glory,” 531–79) was called Chosroes by the Greeks, Kisra by the Arabs; the Persians added the cognomen Anushirvan (“Immortal Soul”). When his older brothers conspired to depose him, he put all his brothers to death, and all their sons but one. His subjects called him “the Just”; and perhaps he merited the title if we separate justice from mercy. Procopius described him as “a past master at feigning piety” and breaking his word;41 but Procopius was of the enemy. The Persian historian al-Tabari praised Khosru’s “penetration, knowledge, intelligence, courage, and prudence,” and put into his mouth an inaugural speech well invented if not true.42 He completely reorganized the government; chose his aides for ability regardless of rank; and raised his son’s tutor, Buzurgmihr, to be a celebrated vizier. He replaced untrained feudal levies with a standing army disciplined and competent. He established a more equitable system of taxation, and consolidated Persian law. He built dams and canals to improve the water supply of the cities and the irrigation of farms; he reclaimed waste lands by giving their cultivators cattle, implements, and seed; he promoted commerce by the construction, repair, and protection of bridges and roads; he devoted his great energy zealously to the service of his people and the state. He encouraged—compelled—marriage on the ground that Persia needed more population to man its fields and frontiers. He persuaded bachelors to marry by dowering the wives, and educating their children, with state funds.43 He maintained and educated orphans and poor children at the public expense. He punished apostasy with death, but tolerated Christianity, even in his harem. He gathered about him philosophers, physicians, and scholars from India and Greece, and delighted to discuss with them the problems of life, government, and death. One discussion turned on the question, “What is the greatest misery?” A Greek philosopher answered, “An impoverished and imbecile old age”; a Hindu replied, “A harassed mind in a diseased body”; Khosru’s vizier won the dutiful acclaim of all by saying, “For my part I think the extreme misery is for a man to see the end of life approaching without having practiced virtue.”44 Khosru supported literature, science, and scholarship with substantial subsidies, and financed many translations and histories; in his reign the university at Jund-i-Shapur reached its apogee. He so guarded the safety of foreigners that his court was always crowded with distinguished visitors from abroad.

On his accession he proclaimed his desire for peace with Rome. Justinian, having designs on Africa and Italy, agreed; and in 532 the two “brothers” signed “an eternal peace.” When Africa and Italy fell, Khosru humorously asked for a share of the spoils on the ground that Byzantium could not have won had not Persia made peace; Justinian sent him costly gifts.45 In 539 Khosru declared war on “Rome,” alleging that Justinian had violated the terms of their treaty; Procopius confirms the charge; probably Khosru thought it wise to attack while Justinian’s armies were still busy in the West, instead of waiting for a victorious and strengthened Byzantium to turn all its forces against Persia; furthermore, it seemed to Khosru manifest destiny that Persia should have the gold mines of Trebizond and an outlet on the Black Sea. He marched into Syria, besieged Hierapolis, Apamea, and Aleppo, spared them for rich ransoms, and soon stood before Antioch. The reckless population, from the battlements, greeted him not merely with arrows and catapult missiles, but with the obscene sarcasm for which it had earned an international reputation.46 The enraged monarch took the city by storm, looted its treasures, burned down all its buildings except the cathedral, massacred part of the population, and sent the remainder away to people a new “Antioch” in Persia. Then he bathed with delight in that Mediterranean which had once been Persia’s western frontier. Justinian dispatched Belisarius to the rescue, but Khosru leisurely crossed the Euphrates with his spoils, and the cautious general did not pursue him (541). The inconclusiveness of the wars between Persia and Rome was doubtless affected by the difficulty of maintaining an occupation force on the enemy’s side of the Syrian desert or the Taurus range; modern improvements in transport and communication have permitted greater wars. In three further invasions of Roman Asia Khosru made rapid marches and sieges, took ransoms and captives, ravaged the countryside, and peaceably retired (542–3). In 545 Justinian paid him 2000 pounds of gold ($840,000) for a five-year truce, and on its expiration 2600 pounds for a five-year extension. Finally (562), after a generation of war, the aging monarchs pledged themselves to peace for fifty years; Justinian agreed to pay Persia annually 30,000 pieces of gold ($7,500,000), and Khosru renounced his claims to disputed territories in the Caucasus and on the Black Sea.

But Khosru was not through with war. About 570, at the request of the Himyarites of southwest Arabia, he sent an army to free them from their Abyssinian conquerors; when the liberation was accomplished the Himyarites found that they were now a Persian province. Justinian had made an alliance with Abyssinia; his successor Justin II considered the Persian expulsion of the Abyssinians from Arabia an unfriendly act; moreover, the Turks on Persia’s eastern border secretly agreed to join in an attaack upon Khosru; Justin declared war (572). Despite his age, Khosru took the field in person, and captured the Roman frontier town of Dara; but his health failed him, he suffered his first defeat (578), and retired to Ctesiphon, where he died in 579, at an uncertain age. In forty-eight years of rule he had won all his wars and battles except one; had extended his empire on every side; had made Persia stronger than ever since Darius I; and had given it so competent a system of administration that when the Arabs conquered Persia they adopted that system practically without change. Almost contemporary with Justinian, he was rated by the common consent of their contemporaries as the greater king; and the Persians of every later generation counted him the strongest and ablest monarch in their history.

His son Hormizd IV (579–89) was overthrown by a general, Bahram Cobin, who made himself regent for Hormizd’s son Khosru II (589), and a year later made himself king. When Khosru came of age he demanded the throne; Bahram refused; Khosru fled to Hierapolis in Roman Syria; the Greek Emperor Maurice offered to restore him to power if Persia would withdraw from Armenia; Khosru agreed, and Ctesiphon had the rare experience of seeing a Roman army install a Persian king (596).

Khosru Parvez (“Victorious”) rose to greater heights of power than any Persian since Xerxes, and prepared his empire’s fall. When Phocas murdered and replaced Maurice, Parvez declared war on the usurper (603) as an act of vengeance for his friend; in effect the ancient contest was renewed. Byzantium being torn by sedition and faction, the Persian armies took Dara, Amida, Edessa, Hierapolis, Aleppo, Apamea, Damascus (605–13). Inflamed with success, Parvez proclaimed a holy war against the Christians; 26,000 Jews joined his army; in 614 his combined forces sacked Jerusalem, and massacred 90,000 Christians.47 Many Christian churches, including that of the Holy Sepulcher, were burned to the ground; and the True Cross, the most cherished of all Christian relics, was carried off to Persia. To Heraclius, the new Emperor, Parvez sent a theological inquiry: “Khosru, greatest of gods and master of the whole earth, to Heraclius, his vile and insensate slave: You say that you trust in your god. Why, then, has he not delivered Jerusalem out of my hands?”48 In 616 a Persian army captured Alexandria; by 619 all Egypt, as not since Darius II, belonged to the King of Kings. Meanwhile another Persian army overran Asia Minor and captured Chalcedon (617); for ten years the Persians held that city, separated from Constantinople only by the narrow Bosporus. During that decade Parvez demolished churches, transported their art and wealth to Persia, and taxed Western Asia into a destitution that left it resourceless against an Arab conquest now only a generation away.

Khosru turned over the conduct of the war to his generals, retired to his luxurious palace at Dastagird (some sixty miles north of Ctesiphon), and gave himself to art and love. He assembled architects, sculptors, and painters to make his new capital outshine the old, and to carve likenesses of Shirin, the fairest and most loved of his 3000 wives. The Persians complained that she was a Christian; some alleged that she had converted the King; in any case, amid his holy war, he allowed her to build many churches and monasteries. But Persia, prospering with spoils and a replenished slave supply, could forgive its king his self-indulgence, his art, even his toleration. It hailed his victories as the final triumph of Persia over Greece and Rome, of Ormuzd over Christ. Alexander at last was answered, and Marathon, Salamis, Plataea, and Arbela were avenged.

Nothing remained of the Byzantine Empire except a few Asiatic ports, some fragments of Italy, Africa, and Greece, an unbeaten navy, and a besieged capital frenzied with terror and despair. Heraclius took ten years to build a new army and state out of the ruins; then, instead of attempting a costly crossing at Chalcedon, he sailed into the Black Sea, crossed Armenia, and attacked Persia in the rear. As Khosru had desecrated Jerusalem, so now Heraclius destroyed Clorumia, birthplace of Zoroaster, and put out its sacred inextinguishable light (624). Khosru sent army after army against him; they were all defeated; and as the Greeks advanced Khosru fled to Ctesiphon. His generals, smarting under his insults, joined the nobles in deposing him. He was imprisoned, and fed on bread and water; eighteen of his sons were slain before his eyes; finally another son, Sheroye, put him to death (628).

III. SASANIAN ART

Of the wealth and splendor of the Shapurs, the Kavadhs, and the Khosrus nothing survives but the ruins of Sasanian art; enough, however, to heighten our wonder at the persistence and adaptability of Persian art from Darius the Great and Persepolis to Shah Abbas the Great and Isfahan.

Extant Sasanian architecture is entirely secular; the fire temples have disappeared, and only royal palaces remain; and these are “gigantic skeletons,”49 with their ornamental stucco facing long since fallen away. The oldest of these ruins is the so-called palace of Ardashir I at Firuzabad, southeast of Shiraz. No one knows its date; guesses range from 340 B.C to A.D. 460. After fifteen centuries of heat and cold, theft and war, the enormous dome still covers a hall one hundred feet high and fifty-five wide. A portal arch eighty-nine feet high and forty-two wide divided a façade 170 feet long; this façade crumbled in our time. From the rectangular central hall squinch arches led up to a circular dome.* By an unusual and interesting arrangement, the pressure of the dome was borne by a double hollow wall, whose inner and outer frames were spanned by a barrel vault; and to this reinforcement of inner by outer wall were added external buttresses of attached pilasters of heavy stones. Here was an architecture quite different from the classic columnar style of Persepolis—crude and clumsy, but using forms that would come to perfection in the St. Sophia of Justinian.

Not far away, at Sarvistan, stands a similar ruin of like uncertain date: a façade of three arches, a great central hall and side rooms, covered by ovoid domes, barrel vaults, and semicupolas serving as buttresses; from these half domes, by removing all but their sustaining framework, the “flying” or skeletal buttress of Gothic architecture may have evolved.51 Northwest of Susa another ruined palace, the Ivan-i-Kharka, shows the oldest known example of the transverse vault, formed with diagonal ribs.52 But the most impressive of Sasanian relics—which frightened the conquering Arabs by its mass—was the royal palace of Ctesiphon, named by the Arabs Taq-i-Kisra, or Arch of Khosru (I). It may be the building described by a Greek historian of A.D. 638, who tells how Justinian “provided Greek marble for Chosroes, and skilled artisans who built for him a palace in the Roman style, not far from Ctesiphon.”53 The north wing collapsed in 1888; the dome is gone; three immense walls rise to a height of one hundred and five feet, with a façade horizontally divided into five tiers of blind arcades. A lofty central arch—the highest (eighty-five feet) and widest (seventy-two feet) elliptical arch known—opened upon a hall one hundred and fifteen by seventy-five feet; the Sasanian kings relished room. These ruined façades imitate the less elegant of Roman front elevations, like the Theater of Marcellus; they are more impressive than beautiful; but we cannot judge past beauty by present ruins.

The most attractive of Sasanian remains are not the gutted palaces of crumbling sun-baked brick, but rock reliefs carved into Persia’s mountainsides. These gigantic figures are lineal descendants of the Achaemenid cliff reliefs, and are in some cases juxtaposed with them, as if to emphasize the continuity of Persian power, and the equality of Sasanian with Achaemenid kings. The oldest of the Sasanian sculptures shows Ardashir trampling upon a fallen foe—presumably the last of the Arsacids. Finer are those at Naqsh-i-Rustam, near Persepolis, celebrating Ardashir, Shapur I, and Bahram II; the kings are drawn as dominating figures, but, like most kings and men, they find it hard to rival the grace and symmetry of the animals. Similar reliefs at Naqsh-i-Redjeb and at Shapur present powerful stone portraits of Shapur I and Bahram I and II. At Taq-i-Bustan—“Arch of the Garden”—near Kermanshah, two column-supported arches are deeply cut into the cliff; reliefs on the inner and outer faces of the arches show Shapur II and Khosru Parvez at the hunt; the stone comes alive with fat elephants and wild pigs; the foliage is carefully done, and the capitals of the columns are handsomely carved. There is in these sculptures no Greek grace of movement or smoothness of line, no keen individualization, no sense of perspective, and little modeling; but in dignity and majesty, in masculine vitality and power, they bear comparison with most of the arch reliefs of imperial Rome.

Apparently these carvings were colored; so were many features of the palaces; but only traces of such painting remain. The literature, however, makes it clear that the art of painting flourished in Sasanian times; the prophet Mani is reported to have founded a school of painting; Firdausi speaks of Persian magnates adorning their mansions with pictures of Iranian heroes;54 and the poet al-Buhturi (d. 897) describes the murals in the palace at Ctesiphon.55 When a Sasanian king died, the best painter of the time was called upon to make a portrait of him for a collection kept in the royal treasury.56

Painting, sculpture, pottery, and other forms of decoration shared their designs with Sasanian textile art. Silks, embroideries, brocades, damasks, tapestries, chair covers, canopies, tents, and rugs were woven with servile patience and masterly skill, and were dyed in warm tints of yellow, blue, and green. Every Persian but the peasant and the priest aspired to dress above his class; presents often took the form of sumptuous garments; and great colorful carpets had been an appanage of wealth in the East since Assyrian days. The two dozen Sasanian textiles that escaped the teeth of time are the most highly valued fabrics in existence.57 Even in their own day Sasanian textiles were admired and imitated from Egypt to Japan; and during the Crusades these pagan products were favored for clothing the relics of Christian saints. When Heraclius captured the palace of Khosru Parvez at Dastagird, delicate embroideries and an immense rug were among his most precious spoils.58 Famous was the “winter carpet” of Khosru Anushirvan, designed to make him forget winter in its spring and summer scenes: flowers and fruits made of inwoven rubies and diamonds grew, in this carpet, beside walks of silver and brooks of pearls traced on a ground of gold.59 Harun al-Rashid prided himself on a spacious Sasanian rug thickly studded with jewelry.60 Persians wrote love poems about their rugs.61

Of Sasanian pottery little remains except pieces of utilitarian intent. Yet the ceramic art was highly developed in Achaemenid times, and must have had some continuance under the Sasanians to reach such perfection in Mohammedan Iran. Ernest Fenellosa thought that Persia might be the center from which the art of enamel spread even to the Far East;62 and art historians debate whether Sasanian Persia or Syria or Byzantium originated lusterware and cloisonné.*63 Sasanian metalworkers made ewers, jugs, bowls, and cups as if for a giant race; turned them on lathes; incised them with graver or chisel, or hammered out a design in repoussé from the obverse side; and used gay animal forms, ranging from cock to lion, as handles and spouts. The famous glass “Cup of Khosru” in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris has medallions of crystal glass inserted into a network of beaten gold; tradition reckons this among the gifts sent by Harun to Charlemagne. The Goths may have learned this art of inlay from Persia, and may have brought it to the West.64

The silversmiths made costly plate, and helped the goldsmiths to adorn lords, ladies, and commoners with jewelry. Several Sasanian silver dishes survive—in the British Museum, the Leningrad Hermitage, the Bibliothéque Nationale, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art; always with kings or nobles at the hunt, and animals more fondly and successfully drawn than men. Sasanian coins sometimes rivaled Rome’s in beauty, as in the issues of Shapur I.65 Even Sasanian books could be works of art; tradition tells how gold and silver trickled from the bindings when Mani’s books were publicly burned.66 Precious materials were also used in Sasanian furniture: Khosru I had a gold table inlaid with costly stones; and Khosru II sent to his savior, the Emperor Maurice, an amber table five feet in diameter, supported on golden feet and encrusted with gems.67

All in all, Sasanian art reveals a laborious recovery after four centuries of Parthian decline. If we may diffidently judge from its remains, it does not equal the Achaemenid in nobility or grandeur, nor the Islamic Persian in inventiveness, delicacy, and taste; but it preserved much of the old virility in its reliefs, and fore-shadowed something of the later exuberance in its decorative themes. It welcomed new ideas and styles, and Khosru I had the good sense to import Greek artists and engineers while defeating Greek generals. Repaying its debt, Sasanian art exported its forms and motives eastward into India, Turkestan, and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt, and Spain. Probably its influence helped to change the emphasis in Greek art from classic representation to Byzantine ornament, and in Latin Christian art from wooden ceilings to brick or stone vaults and domes and buttressed walls. The great portals and cupolas of Sasanian architecture passed down into Moslem mosques and Mogul palaces and shrines. Nothing is lost in history: sooner or later every creative idea finds opportunity and development, and adds its color to the flame of life.

IV. THE ARAB CONQUEST

Having killed and succeeded his father, Sheroye—crowned as Kavadh II—made peace with Heraclius; surrendered Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, and western Mesopotamia; returned to their countries the captives taken by Persia; and restored to Jerusalem the remains of the True Cross. Heraclius reasonably rejoiced over so thorough a triumph; he did not observe that on the very day in 629 when he replaced the True Cross in its shrine a band of Arabs attacked a Greek garrison near the River Jordan. In that same year pestilence broke out in Persia; thousands died of it, including the King. His son Ardashir III, aged seven, was proclaimed ruler; a general, Shahr-Baraz, killed the boy and usurped the throne; his own soldiers killed Shahr-Baraz, and dragged his corpse through the streets of Ctesiphon, shouting, “Whoever, not being of royal blood, seats himself upon the throne of Persia, will share this fate”; the populace is always more royalist than the king. Anarchy now swept through a realm exhausted by twenty-six years of war. Social disintegration climaxed a moral decay that had come with the riches of victory.68 In four years nine rulers contested the throne, and disappeared through assassination, or flight, or an abnormally natural death. Provinces, even cities, declared their independence of a central government no longer able to rule. In 634 the crown was given to Yezdegird III, scion of the house of Sasan, and son of a Negress.69

In 632 Mohammed died after founding a new Arab state. His second successor, the Caliph Omar, received in 634 a letter from Muthanna, his general in Syria, informing him that Persia was in chaos and ripe for conquest.70 Omar assigned the task to his most brilliant commander, Khalid. With an army of Bedouin Arabs inured to conflict and hungry for spoils, Khalid marched along the south shore of the Persian Gulf, and sent a characteristic message to Hormizd, governor of the frontier province: “Accept Islam, and thou art safe; else pay tribute. … A people is already upon thee, loving death even as thou lovest life.”71 Hormizd challenged him to single combat; Khalid accepted, and slew him. Overcoming all resistance, the Moslems reached the Euphrates; Khalid was recalled to save an Arab army elsewhere; Muthanna replaced him, and, with reinforcements, crossed the river on a bridge of boats. Yezdegird, still a youth of twenty-two, gave the supreme command to Rustam, governor of Khurasan, and bade him raise a limitless force to save the state. The Persians met the Arabs in the Battle of the Bridge, defeated them, and pursued them recklessly; Muthanna re-formed his columns, and at the Battle of El-Bowayb destroyed the disordered Persian forces almost to a man (624). Moslem losses were heavy; Muthanna died of his wounds; but the Caliph sent an abler general, Saad, and a new army of 30,000 men. Yezdegird replied by arming 120,000 Persians. Rustam led them across the Euphrates to Kadisiya, and there through four bloody days was fought one of the decisive battles of Asiatic history. On the fourth day a sandstorm blew into the faces of the Persians; the Arabs seized the opportunity, and overwhelmed their blinded enemies. Rustam was killed, and his army dispersed (636). Saad led his unresisted troops to the Tigris, crossed it, and entered Ctesiphon.

The simple and hardy Arabs gazed in wonder at the royal palace, its mighty arch and marble hall, its enormous carpets and jeweled throne. For ten days they labored to carry off their spoils. Perhaps because of these impediments, Omar forbade Saad to advance farther east; “Iraq,” he said, “is enough.”72 Saad complied, and spent the next three years establishing Arab rule throughout Mesopotamia. Meanwhile Yezdegird, in his northern provinces, raised another army, 150,000 strong; Omar sent against him 30,000 men; at Nahavand superior tactics won the “Victory of Victories” for the Arabs; 100,000 Persians, caught in narrow defiles, were massacred (641). Soon all Persia was in Arab hands. Yezdegird fled to Balkh, begged aid of China and was refused, begged aid of the Turks and was given a small force; but as he started out on his new campaign some Turkish soldiers murdered him for his jewelry (652). Sasanian Persia had come to an end.

BOOK II

ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION

569–1258

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE FOR BOOK II

570–632:

Mohammed

610:

Mohammed’s vision

622:

His Hegira to Medina

630:

Mohammed takes Mecca

632–4:

Abu Bekr caliph

634–44:

Omar caliph

635:

Moslems take Damascus

637:

and Jerusalem & Ctesiphon

641:

Moslems conquer Persia & Egypt

641:

Moslems found Cairo (Fustat)

642:

Mosque of Amr at Cairo

644–56:

Othman caliph

656–60:

Ali caliph

660–80:

Muawiya I caliph

660–750:

Umayyad caliphate at Damascus

662:

Hindu numerals in Syria

680:

Husein slain at Kerbela

680–3:

Yezid I caliph

683–4:

Muawiya II caliph

685–705:

Abd-al-Malik caliph

691–4:

Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem

693–862:

Moslem rule in Armenia

698:

Moslems take Carthage

705–15:

Walid I caliph

705f:

Great Mosque of Damascus

711:

Moslems enter Spain

715–17:

Suleiman I caliph

717–20:

Omar II caliph

720–4:

Yezid II caliph

724–43:

Hisham caliph

732:

Moslems turned back at Tours

743:

The Mshatta reliefs

743–4:

Walid II caliph

750:

Abu’l-Abbas al-Saffah founds Abbasid caliphate

754–75:

Al-Mansur caliph; Baghdad becomes capital

755–88:

Abd-er-Rahman I emir of Cordova

757–847:

The Mutazilite philosophers

760:

Rise of the Ismaili sect

775–86:

Al-Mahdi caliph

786f:

Blue Mosque of Cordova

786–809:

Harun al-Rashid caliph

780–974:

Idrisid dynasty at Fez

803:

Fall of the Barmakid family

803f:

Al-Kindi, philosopher

808–909:

Aghlabid dynasty at Qairuan

809–10:

Moslems take Corsica and Sardinia

809–77:

Hunain ibn Ishaq, scholar

813–33:

Al-Mamun caliph

820–72:

Tahirid dynasty in Persia

822–52:

Abd-er-Rahman II emir of Cordova

827f:

Saracens conquer Sicily

830:

“House of Wisdom” at Baghdad

830:

Al-Khwarizmi’s Algebra

844–926:

Al-Razi, physician

846:

Saracens attack Rome

870–950:

Al-Farabi, philosopher

872–903:

Saffarid dynasty in Persia

873–935:

Al-Ashari, theologian

878:

Mosque of Ibn Tulun at Cairo

909f:

Fatimid caliphate at Qairuan

912–61:

Abd-er-Rahman caliph at Cordova

915:

fl. al-Tabari, historian

915–65:

Al-Mutannabi, poet

934–1020:

Firdausi, poet

940–98:

Abu’l Wafa, mathematician

945–1058:

Buwayhid ascendancy in Baghdad

951:

d. of al-Masudi, geographer

952–77:

Ashot III and 990–1020: Gagik I: Golden Age of Medieval Armenia

961–76:

Al-Hakam caliph at Cordova

965–1039:

Al-Haitham, physicist

967–1049:

Abu Said, Sufi poet

969–1171:

Fatimid dynasty at Cairo

970:

Mosque of el-Azhar at Cairo

973–1048:

Al-Biruni, scientist

973–1058:

Al-Ma’arri, poet

976–1010:

Al-Hisham caliph at Cordova

978–1002:

Almanzor prime minister at Cordova

980–1037:

Ibn Sina (Avicenna), philosopher

983f:

Brethren of Sincerity

990–1012:

Mosque of al-Hakim at Cairo

998–1030:

Mahmud of Ghazna

1012:

Berber revolution at Cordova

1017–92:

Nizam al-Mulk, vizier

1031:

End of Cordova caliphate

1038:

Seljuq Turks invade Persia

1038–1123:

Omar Khayyam, poet

1040–95:

Al-Mutamid, emir and poet

1058:

Seljuqs take Baghdad

1058–1111:

Al-Ghazali, theologian

1059–63:

Tughril Beg sultan at Baghdad

1060:

Seljuq Turks conquer Armenia

1063–72:

Alp Arslan sultan

1071:

Turks defeat Greeks at Manzikert

1072–92:

Malik Shah sultan

1077–1327:

Sultanate of Roum in Asia Minor

1088f:

Friday Mosque at Isfahan

1090:

“Assassin” sect founded

1090–1147:

Almoravid dynasty in Spain

1091–1162:

Ibn Zohr, physician

1098:

Fatimids take Jerusalem

1100–66:

Al-Idrisi, geographer

1106f:

fl. Ibn Bajja, philosopher

1107–85:

Ibn Tufail, philosopher

1117–51:

Sanjar, Seljuq sultan

1126–98:

Ibn Rushd (Averroës), phil’r

1130–1269:

Almohad dynasty in Morocco

1138–93:

Saladin

1148–1248:

Almohad dynasty in Spain

1162–1227:

Jenghiz Khan

1175–1249:

Ayyubid dynasty

1179–1220:

Yaqut, geographer

1181f:

Alcazar of Seville

1184–1291:

Sa’di, poet

1187:

Saladin defeats Crusaders at Hattin & takes Jerusalem

1188:

fl. Nizami, poet

1196:

Giralda tower at Seville

1201–73:

Jalal-ud-Din Rumi, poet

1211–82:

Ibn Khallikan, biographer

1212:

Christians defeat Moors at Las Navas de Toledo

1218–38:

Al-Kamil sultan at Cairo

1219:

Jenghiz Khan invades Transoxiana

1245:

Mongols take Jerusalem

1248f:

The Alhambra

1250–1517:

Mamluk rule in Egypt

1252:

Moorish rule in Spain confined to Granada

1258:

Mongols sack Baghdad; end of Abbasid caliphate

1260: