FICTIONS

“A world of disorderly notions, picked out of his books, crowded into his imagination.”—Don Quixote in his library

What do we see when we read?

(Other than words on a page.)

What do we picture in our minds?

The story of reading is a remembered story. When we read, we are immersed. And the more we are immersed, the less we are able, in the moment, to bring our analytic minds to bear upon the experience in which we are absorbed. Thus, when we discuss the feeling of reading we are really talking about the memory of having read.*

*William James describes the impossible attempt to introspectively examine our own consciousness as “trying to turn up the gas quickly enough to see how the darkness looks.”

And this memory of reading is a false memory.

When we remember the experience of reading a book, we imagine a continuous unfolding of images.

For instance, I remember reading Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina:

“I saw Anna; I saw Anna’s house …”

We imagine that the experience of reading is like that of watching a film.

But this is not what actually happens—this is neither what reading is, nor what reading is like.

If I said to you, “Describe Anna Karenina,” perhaps you’d mention her beauty. If you were reading closely you’d mention her “thick lashes,” her weight, or maybe even her little downy mustache (yes—it’s there). Mathew Arnold remarks upon “Anna’s shoulders, and masses of hair, and half-shut eyes …”

But what does Anna Karenina look like? You may feel intimately acquainted with a character (people like to say, of a brilliantly described character, “it’s like I know her”), but this doesn’t mean you are actually picturing a person. Nothing so fixed—nothing so choate.

***

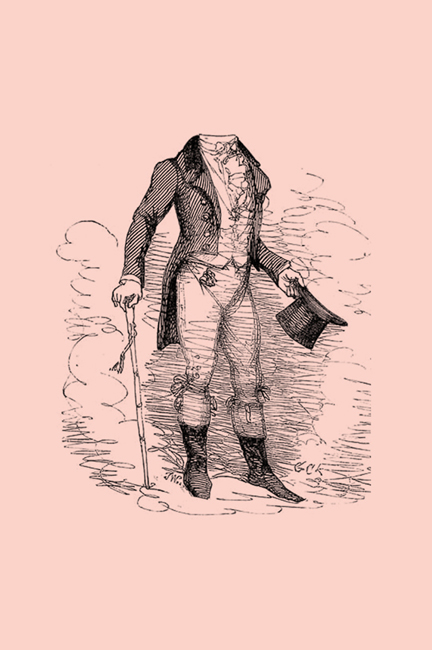

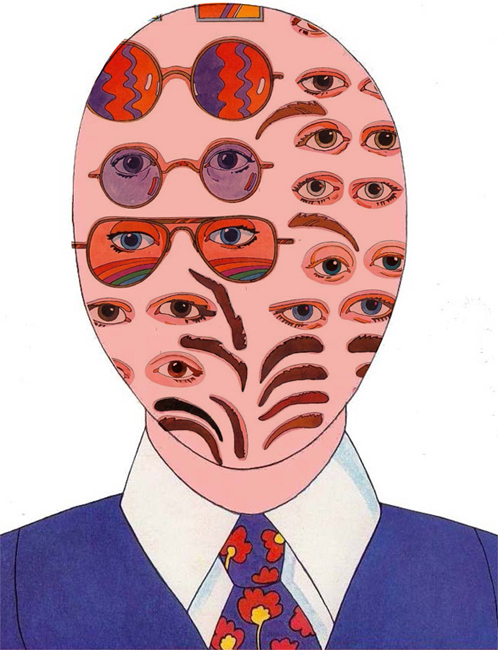

Most authors (wittingly, unwittingly) provide their fictional characters with more behavior than physical description. Even if an author excels at physical description, we are left with shambling concoctions of stray body parts and random detail (authors can’t tell us everything). We fill in gaps. We shade them in. We gloss over them. We elide. Anna: her hair, her weight—these are facets only, and do not make up a true image of a person. They make up a body type, a hair color…What does Anna look like? We don’t know—our mental sketches of characters are worse than police composites.

Anna Karenina, rendered by police composite-sketch software based on the descriptions in Tolstoy’s text. (I always imagined her hair as being more tightly curled, and blacker…)

Visualizing seems to require will…

…though at times it may also seem as though an image of a sort appears to us unbidden.

(It is tenuous, and withdraws shyly upon scrutiny.)

I canvass readers. I ask them if they can clearly imagine their favorite characters. To these readers, a beloved character is, to borrow William Shakespeare’s phrase, “bodied forth.”

These readers contend that the success of a work of fiction hinges on the putative authenticity of the characters. Some readers go further and suggest that the only way they can enjoy a novel is if the main characters are easily visible:

“Can you picture, in your mind, what Anna Karenina looks like?” I ask.

“Yes,” they say, “as if she were standing here in front of me.”

“What does her nose look like?”

“I hadn’t thought it out; but now that I think of it, she would be the kind of person who would have a nose like …”

“But wait—how did you picture her before I asked? Noseless?”

“Well …”

“Does she have a heavy brow? Bangs? Where does she hold her weight? Does she slouch? Does she have laugh lines?”

(Only a very tedious writer would tell you this much about a character.*)

***

*Though Tolstoy never tires of mentioning Anna’s slender hands. What does this emblematic description signify for Tolstoy?

Some readers swear they can picture these characters perfectly, but only while they are reading. I doubt this, but I wonder now if our images of characters are vague because our visual memories are vague in general.

***

A thought experiment: Picture your mother. Now picture your favorite literary character. (Or: Picture your home. Then picture Howards End.) The difference between your mother’s afterimage and that of a literary character you love is that the more you concentrate, the more your mother might come into focus. A character will not reveal herself so easily. (The closer you look, the farther away she gets.)

(Actually, this is a relief. When I impose a face on a fictional character, the effect isn’t one of recognition, but dissonance. I end up imagining someone I know.* And then I think: That isn’t Anna!)

*I recently had the experience while reading a novel wherein I thought I had clearly “seen” a character, a society woman with “widely spaced eyes.” When I subsequently scrutinized my imagination, I discovered that what I had been imagining was the face of one of my coworkers, grafted onto the body of an elderly friend of my grandmother’s. When brought into focus, this was not a pleasant sight.

Often, when I ask someone to describe the physical appearance of a key character from their favorite book they will tell me how this character moves through space. (Much of what takes place in fiction is choreographic.)

One reader told me Benjy Compson from William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury was “lumbering, uncoordinated …”

But what does he look like?

***

Literary characters are physically vague—they have only a few features, and these features hardly seem to matter—or, rather, these features matter only in that they help to refine a character’s meaning. Character description is a kind of circumscription. A character’s features help to delineate their boundaries—but these features don’t help us truly picture a person.*

*Or is it that comprehensiveness is not an important factor in the identification of anything?

***

It is precisely what the text does not elucidate that becomes an invitation to our imaginations. So I ask myself: Is it that we imagine the most, or the most vividly, when an author is at his most elliptical or withholding?

(In music, notes and chords define ideas, but so do rests.)

William Gass, on Mr. Cashmore from Henry James’s The Awkward Age:

We can imagine any number of other sentences about Mr. Cashmore added … now the question is: what is Mr. Cashmore? Here is the answer I shall give: Mr. Cashmore is (1) a noise, (2) a proper name, (3) a complex system of ideas, (4) a controlling perception, (5) an instrument of verbal organization, (6) a pretended mode of referring, and (7) a source of verbal energy.

The same could be said of any character—of Nanda, from the same book, or of Anna Karenina. Of course—isn’t the fact that Anna is ineluctably drawn to Vronsky (and feels trapped in her marriage) more significant than the mere morphological fact of her being, say, “full-figured”?

It is how characters behave, in relation to everyone and everything in their fictional, delineated world, that ultimately matters. (“Lumbering, uncoordinated …”)

Though we may think of characters as visible, they are more like a set of rules that determines a particular outcome. A character’s physical attributes may be ornamental, but their features can also contribute to their meaning.

(What is the difference between seeing and understanding?)

A = Anna is young and pretty (is in possession of “slender hands”; is pleasingly plump; is pale and blushing; has masses of dark curly hair; etc.)

K = Karenin is old and ugly.

V = Vronsky is young and handsome.

M = Mores: i.e., the condemnation of extramarital affairs (by women) in nineteenth-century Russia

T = Anna will be killed by a train.

“a,” “k,” & “v” = Anna, Karenin, & Vronsky

Take Karenin’s ears…

(Karenin is the cuckolded husband of Anna Karenina.)

Are his ears large or small?

At Petersburg, so soon as the train stopped and she got out, the first person that attracted her attention was her husband. ‘Oh, mercy! Why do his ears look like that?’ she thought, looking at his frigid and imposing figure, and especially the ears that struck her at the moment as propping up the brim of his round hat…

Karenin’s ears grow in proportion to his wife’s disaffection with him. In this way, these ears tell us nothing about how Karenin looks, and a great deal about how Anna feels.

Ishmael.”

What happens when you read the first line of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick?

You are being addressed, but by whom? Chances are you hear the line (in your mind’s ear) before you picture the speaker. I can hear Ishmael’s words more clearly than I can see his face. (Audition requires different neurological processes than vision, or smell. And I would suggest that we hear more than we see while we are reading.)

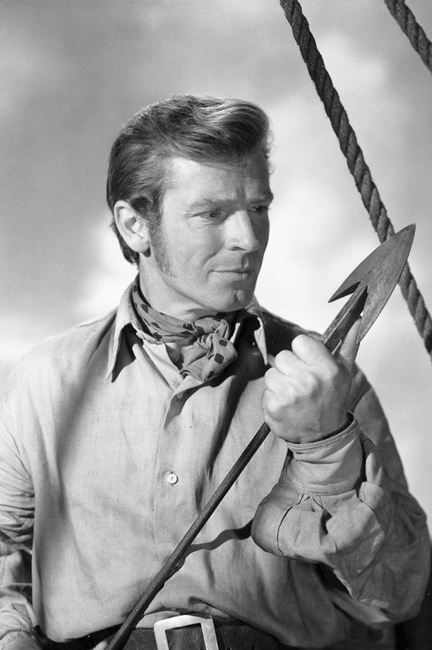

If you did manage to summon an image of Ishmael, what did you come up with? A seafaring man of some sort? (Is this a picture or a category?) Do you picture Richard Basehart, the actor in the John Huston adaptation?

(One should watch a film adaptation of a favorite book only after considering, very carefully, the fact that the casting of the film may very well become the permanent casting of the book in one’s mind. This is a very real hazard.)

***

What color is your Ishmael’s hair? Is it curly or straight? Is he taller than you? If you don’t picture him clearly, do you merely set aside a chit, a placeholder that says, “Protagonist, narrator—first person”? Maybe this is enough. Ishmael probably evokes a feeling in you—but this is not the same as seeing him.

Maybe Melville had a specific image in mind for his Ishmael. Maybe Ishmael looked like someone he knew from his years at sea. But Melville’s image is not ours. And no matter how well illustrated Ishmael may or may not be (I can’t remember if Melville describes Ishmael’s physical attributes, and I’ve read the book three times), chances are we will have to constantly revise our image of him as the book progresses. We are ever reviewing and reconsidering our mental portraits of characters in novels: amending them, backtracking to check on them, updating them when new information arises…

What kind of face you assign to Ishmael might depend upon what mood you are in on a particular day. Ishmael might look as different from one chapter to the next as, say, Tashtego does from Stubb.

Sometimes, in a play, several actors perform a single role. In these instances, the cognitive dissonance aroused by multiple actors is evident to the theatrical audience. But after reading a novel, we think back on its characters as if they were played by single actors. (In a narrative, multiplicity of “character” is read as psychological complexity.)

***

A question: Emma Bovary’s eye color (famously) changes during the course of Gustave Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary. Blue, brown, deep black … Does this matter?

It doesn’t appear to.

***

“I feel sorry for novelists when they have to mention women’s eyes: there’s so little choice … Her eyes are blue: innocence and honesty. Her eyes are black: passion and depth. Her eyes are green: wildness and jealousy. Her eyes are brown: reliability and common sense. Her eyes are violet: the novel is by Raymond Chandler.”

—Julian Barnes, Flaubert’s Parrot

Another question: As a character develops throughout the course of a novel, does the way this character “looks” to you (their appearance) change … as a result of their inner development? (A real person may become more beautiful to us once we are better acquainted with their nature—and in these cases our increased affection isn’t due to some closer physical observation.)

Are characters complete as soon as they are introduced? Perhaps they are complete, but just out of order; the way a puzzle might be.

***

To the Lighthouse is a novel that is exemplary for, among other merits, its close descriptions of sensory and psychological experience. The raw material of the book isn’t as much character, place, and plot as it is sense data.

The book opens like this:

“ ‘Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow,’ said Mrs. Ramsay.”

I imagine these words echoing in a void. Who is Mrs. Ramsay? Where is she? She is speaking to someone. Two faceless people in a void—inchoate and unconstituted.

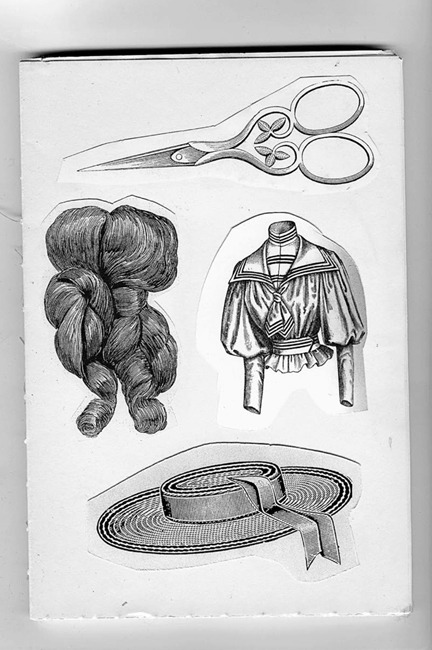

As we read on, Mrs. Ramsay becomes a collage, composed of clippings, like the ones in her son James’s book.

***

Mrs. Ramsay is speaking to her son, we are told. Is she, perhaps, seventy—and he fifty? No, we learn that he is only six. Revisions are made. And so on. If fiction were linear we would learn to wait, in order to picture. But we don’t wait. We begin imaging right out of the gate, immediately upon beginning a book.

When we remember reading books, we don’t remember having made these constant little adjustments.

Once again: We simply remember it as if we had watched the movie…

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ