MAPS

& RULES

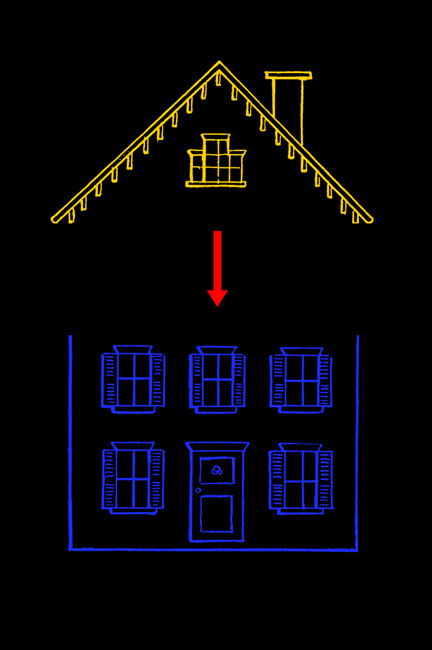

The action in To the Lighthouse unfolds at a house in the Hebrides. If you asked me to describe the house, I could tell you some of its features. But much like my mental picture of Anna Karenina, the house is a shutter here, a dormer there.

There’s nothing to keep the rain out! Now I picture a roof. I still don’t know if it’s slate or shingle. Shingle. I’ve decided. (Sometimes our choices are significant—sometimes not.)

I know that on the Ramsays’ property there is a garden, and a hedge. A view of the ocean and the lighthouse. I know the rough placements of the characters on this stage. I have mapped the surroundings, but mapping isn’t exactly picturing—not in the sense of re-creating the world, as it appears to us, visually.

(Nabokov also used to map novels.)

I do this too on occasion. I’ve mapped To the Lighthouse.

But I still can’t describe the Ramsays’ house.

Our maps of fictional settings, like our maps of real settings, perform a function. A map that guides us to a wedding reception is not a picture—a picture of what the wedding reception will look like—but rather, it is a set of guidelines. And our mental maps of the Ramsay house are no different—they govern the actions of its occupants.

William Gass (again):

We do visualize, I suppose. Where did I leave my gloves? And then I ransack the room in my mind until I find them. But the room I ransack is abstract—a simple schema … and I think of the room as a set of likely glove locations…

The Ramsay house is a set of likely Ramsay locations.

Visibility can be confused with credibility. Some books seem as though they are presenting us with imagery, but are actually presenting us with fictional facts. Or rather, these books predicate their plausibility, and for the reader, their conceivability, on an accretion of detail and lore. J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is one such text. The endpapers tell the readers that they might like to know the location of Rivendell, and the appendix suggests that it might be prudent to learn Elvish. (Endpaper maps are always tip-offs that one is entering just such a book/compendium-of-knowledge.)

These books demand scholarship. (The scholarship demanded is a large part of the appeal of such books.) One can learn about the myths and legends of Middle Earth as one can acquaint oneself with its flora and fauna. (One can similarly investigate the fictional worlds of non-fantasy-genre novels—for instance, the “Organization of North American Nations” in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest.)

Simulacrum worlds such as these require that their constituent parts, their contents, seem endless. The authors lead us down a narrative path, but we always have the impression that we could leave that trail and bushwhack, and at the end of our wanderings, we’d find the unlit parts of these worlds intact and replete with nuance.

However: an author does not need to stockpile detail in order to create a credible world (or character).

A shape may be defined by a set of points that lie on its perimeter—nothing more is needed. Or: a rule can be determined.

W. H. Auden writes of The Lord of the Rings: “It is a world of intelligible law.”

What is crucial in the formulation of a rule or function is its applicability. The user must possess the ability to apply the rule forward. (The function, and those who apply it, must be able to “go on.”)

The same can be said of, say, a character. Anna can be defined by several discrete points (her hands are small; her hair is dark and curly) or through a function (Anna is graceful*).

*Unlike how she appears in earlier drafts of the novel, wherein (as Richard Pevear tells us in the introduction to his new translation of the book) Anna is portrayed as “graceless” and rude.

ТЕЛЕГРАМ

ТЕЛЕГРАМ Книжный Вестник

Книжный Вестник Поиск книг

Поиск книг Любовные романы

Любовные романы Саморазвитие

Саморазвитие Детективы

Детективы Фантастика

Фантастика Классика

Классика ВКОНТАКТЕ

ВКОНТАКТЕ