THE CAMBRIDGE ANCIENT HISTORY

VOLUME X

THE CAMBRIDGE ANCIENT HISTORY

SECOND EDITION

VOLUME X

The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C.—a.d. 69

edited by ALAN K. BOWMAN

Student of Christ Church, Oxford

EDWARD CHAMPLIN

Professor of Classics, Princeton University

ANDREW LINTOTT

Fellow and Tutor in Ancient History, Worcester College, Oxford

Cambridge

UNIVERSITY PRESS

published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom

cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vie 32.07, Australia

Ruiz de Alarcon 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa

http://www.cambridge.org

© Cambridge University Press 1996

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 1996 Fifth printing 2006

Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Catalogue card number: 75-85719

isbn 0 521 26430 8 hardback

CONTENTS

'List of maps page xiv

List of text-figures xv

List of tables xv

List of stemmata xv

Preface xix

PART I NARRATIVE

The triumviral period i by Christopher pelling, Fellow andPraelector in

Classics, University College, Oxford

I The triumvirate i

II Philippi, 42 b.c. 5

The East, 42—40 в.с. 9

Perusia, 41-40 в.с. 14 V Brundisium and Misenum, 40-39 b.c. 17

VI The East, 39-37 в.с. zi

VII Tarentum, 37 в.с. 24

VIII The year 36 в.с. 27

IX 35—33 в.с. 36

X Preparation: 3 2 B.C. 48

XI Actium, 31 в.с. 54

XII Alexandria, 30 в.с. 59

XIII Retrospect 65

Endnote: Constitutional questions 67

Political history, 30 в.с. to a.d. 14 70 by j. a. crook, Fellow of St John's College, and Emeritus Professor of Ancient History in the University of Cambridge

I Introduction 70

II 30-17 в.с. 73

III 16 b.c.—a.d. 14 94Augustus: power, authority, achievement 113 by j.a. crook

I Power 113

II Authority 117

III Achievement 123

The expansion of the empire under Augustus 147 by erich s. gruen, Professor of History and Classics,

University of California, Berkeley

Egypt, Ethiopia and Arabia 148 II Asia Minor 151

Judaea and Syria 154

Armenia and Parthia 15 8

Spain 163 VI Africa 166

VII The Alps 169

VIII The Balkans 171

IX Germany 178

X Imperial ideology 188

XI Conclusion 194

Tiberius to Nero 198 by т. e.j. Wiedemann, Reader in the History of the Roman Empire, University of Bristol

I The accession of Tiberius and the nature of politics

under the Julio-Claudians 198

II The reign of Tiberius 209

Gaius Caligula 221

Claudius 229

Nero 241

From Nero to Vespasian 2 5 6 by t.e.j. wiedemann

I A.D. 68 256

II A.d. 69—70 265

PART II THE GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION OF THE EMPIRE

The imperial court 283 by andrew wallace-hadrill, Professor of Classics at

the University of Reading

I Introduction 283

Access and ritual: court society 285

Patronage, power and government 296

Conclusion 306

The Imperial finances 309 by d. w. rath bone, Reader in Ancient History, King's

College London

The Senate and senatorial and equestrian posts 3 24 by Richard j.a. talbert, William Rand Kenan, Jr,

Professor of History, and Adjunct Professor of Classics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

I The Senate 324

II Senatorial and equestrian posts 357

Provincial administration and taxation 344

by ALAN K. BOWMAN

I Rome, the emperor and the provinces 344

II Structure 351

Function 357

Conclusion 367

The army and the navy ■ 371 by lawrence keppie, Reader in Roman Archaeology, Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow

I The army of the late Republic 371

II The army in the civil wars, 49-30 b.c. 373

The army and navy of Augustus 3 76

Army and navy under the Julio-Claudians 387 V The Roman army in a.d. 70 393

The administration of justice 397 by h. galsterer, Professor of Ancient History at the

Rheinische Friedrich- Wtlhelms- Universitdt, Bonn

PART III ITALY AND THE PROVINCES

The West 414

13a Italy and Rome from Sulla to Augustus 414

by m. h. Crawford, Professor of Ancient History, University College London

I Extent of Romanization 414

II Survival of local cultures 424

13 b Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica 434

by r.j. a. Wilson, Professor of Archaeology, University of Nottinghamijf Spain 449

by g. alfoldy, Professor of Ancient History in the University of Heidelberg

I Conquest, provincial administration and military

organization 449

II Urbanization 455

Economy and society 458

The impact of Romanization 461

13 d Gaul 464 by c. goudineau, Profosseur du College de France (chaire d' Antiquites nationales)

I Introduction 464

II Gallia Narbonensis 471

III Tres Galliae 487

13* Britain 43 в.с. to a.d. 69 503 by john wacher, Emeritus Professor of Archaeology, University of Leicester

I Pre-conquest period 503

II The invasion and its aftermath 5 06

Organization of the province 510

Urbanization and communications 511 V Rural settlement 513

VI Trade and industry 514

VII Religion 515

13/ Germany 517 by c. ruger, Honorary Professor, Bonn University

I Introduction 517

II Roman Germany, 16 b.c.-a.d. 17 524

III The period of the establishment of the military zone

(a.d. 14-90) 528

13g Raetia 535

by h. wolff, Professor of Ancient History, University of Passau

I 'Raetia' before Claudius 537

The Claudian province 541

13h The Danubian and Balkan provinces 545

by j.j. wilkes, Yates Professor of Greek and Roman Archaeology, University College London

I The advance to the Danube and beyond, 43 b.c.-a.d. 6 545

II Rebellion in Illyricum and the annexation of Thrace (a.d.

6-69) 5 5 3

The Danube peoples 5 5 8

IV Provinces and armies 565

Roman colonization and the organization of the native

peoples 573

13i Roman Africa: Augustus to Vespasian 586 by c.r. whittaker, Fellow of Churchill College, and formerly Lecturer in Classics in the University of Cambridge

I Before Augustus 586

II Africa and the civil wars, 44—51 b.c. 590

Augustan expansion 591

Tiberius and Tacfarinas 593

Gaius to Nero 5 96

VI The administration and organization of the province 600

VII Cities and colonies 603

VIII Romanization and resistance 610

IX The economy 615

X Roman imperialism 616

13/ Cyrene 619 by joyce Reynolds, Fellow of Newnham College, and Emeritus Reader in Roman Historical Epigraphy in the University of Cambridge and j. a. lloyd, Lecturer in Archaeology in the University of Oxford, and Fellow of Wolf son College

I Introduction 619

II The country 622

The population, its distribution, organization and

internal relationships 625

From the death of Caesar to the close of the Marmaric

War (c. a.d. 6/7) 630

a.d. 4-7O 636

14 The East 641

14л Greece (including Crete and Cyprus) and Asia Minor

from 43 b.c. to a.d. 69 641 by в. m. levic к, Fellow and Tutor in Ancient History, St Hilda's College, Oxford

I Geography and development 641

II The triumviral period 645

The Augustan restoration 647

Consolidation under the Julio-Claudians 663

Conclusion: first fruits 672

14b Egypt 676

by alan k. bowman

I The Roman conquest 676

II Bureaucracy and administration 679

Economy and society 693

Alexandria 699 V Conclusion 702

14c Syria 703

by DAVID Kennedy, Senior Lecturer, Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Western Australia

I Introduction 703

Establishment and development of the province 708

Client states 728

Conclusion 736

iJudaea 737 by martin Goodman, Reader in Jewish Studies, University of Oxford, and Yellow of Wolf son College

I The Herods 737

II Roman administration 750

Jewish religion and society 761

Conclusion 780

PART IV ROMAN SOCIETY AND CULTURE UNDER THE JULIO-CLAUDIANS

Rome and its development under Augustus and his successors 782 by Nicholas purcell, Fellow and Tutor in Ancient

History, St John's College, Oxford

The place of religion: Rome in the early Empire 812

by s. r. f. price, Fellow and Tutor in Ancient History, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

I Myths and place 814

II The re-placing of Roman religion 820

Imperial rituals 837

Rome and Her empire 841

The origins and spread of Christianity 848 by g.w. clarke, Director, Humanities Research Centre, and Professor of Classical Studies, Australian National University

I Origins and spread 848

II Christians and the law 866

III Conclusion 871

Social status and social legislation 873 by susan treggiari, Professor of Classics and Bass

Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, Stanford University

I Legal distinctions 873

II Social distinctions 875

Social problems at the beginning of the Principate 883

The social legislation of Augustus and the Julio-

Claudians 886

The impact of the Principate on society 897

Literature and society 905 by Gavin townend, Emeritus Professor of Eat in in the University of Durham

Definition of the period 905

Patronage and its obligations 907

Rhetoric and escapism 916

The justification of literature 921

The accessibility of literature 926

Roman art, 43 в.с. to a.d. 69 930 by Mario torelli, Professor of Archaeology and the

History of Greek and Roman Art, University of Perugia

I The general characteristics of Augustan Classicism 930

The creation of the Augustan model 934

From Tiberius to Nero: the crisis of the model 952

Early classical private law 959 by bruce w. frier, Professor of Classics and Roman Earn, University of Michigan

I The jurists and the Principate 959

II Augustus' procedural reforms 961

Labeo 964

Proculians and Sabinians 969

Legal writing and education 973 VI Imperial intervention 974

VII The Flavian jurists 97^

Appendices to chapter 13a by м.н. crawford

I Consular dating formulae in republican Italy 979

II Survival of Greek language and institutions 981

Inscriptions in languages other than Latin after the

Social War 983

Italian calendars 985

Votive deposits 987 VI Epichoric funerary practices 987

VII Diffusion of alien grave stelae 989

Stemmata 990

Chronological table 995

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations page 1006

A General studies 1015

В Sources 1019

Works on ancient authors 1 о 19

Epigraphy 1027

Numismatics 1031

Papyrology 1034

С Political history 1035

The triumviral period and the reign of Augustus 103 5

The expansion of the empire, 43.b.c.-a.d. 69 1044

The Julio-Claudians and the year a.d. 69 1047

D Government and administration 1050

The imperial court 1050

The Senate and the equities 105 1

Provincial administration 1053

The imperial wealth io54

The army and the navy 1056

The administration of justice 1059

E Italy and the provinces 1061

Italy 1061

Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica 1066

Spain 1068

Gaul 1070

Britain 1082

Germany 1083

Raetia 1084

The Balkans 1086

Africa 1089

Cyrene 1091

Greece and Asia Minor io93

Egypt 1097

Syria 1100

Judaea 1104

F Society, religion and culture 1111

Society and its institutions 1111

Religion 1114

Art and architecture 1120

Law 113 5

Index 113 8

NOTE ON THE BIBLIOGRAPHY The bibliography is arranged in sections dealing with specific topics, which sometimes correspond to individual chapters but more often combine the contents of several chapters. References in the footnotes are to these sections (which are distinguished by capital letters) and within these sections each book or article has assigned to it a number which is quoted in the footnotes. In these, so as to provide a quick indication of the nature of the work referred to, the author's name and the date of publication are also included in each reference. Thus 'Syme 1986 (a 95) 50' signifies 'R. Syme, The Augustan Revolution, Oxford, 1986, p. 50', to be found in Section a of the bibliography as item 95.MAPS

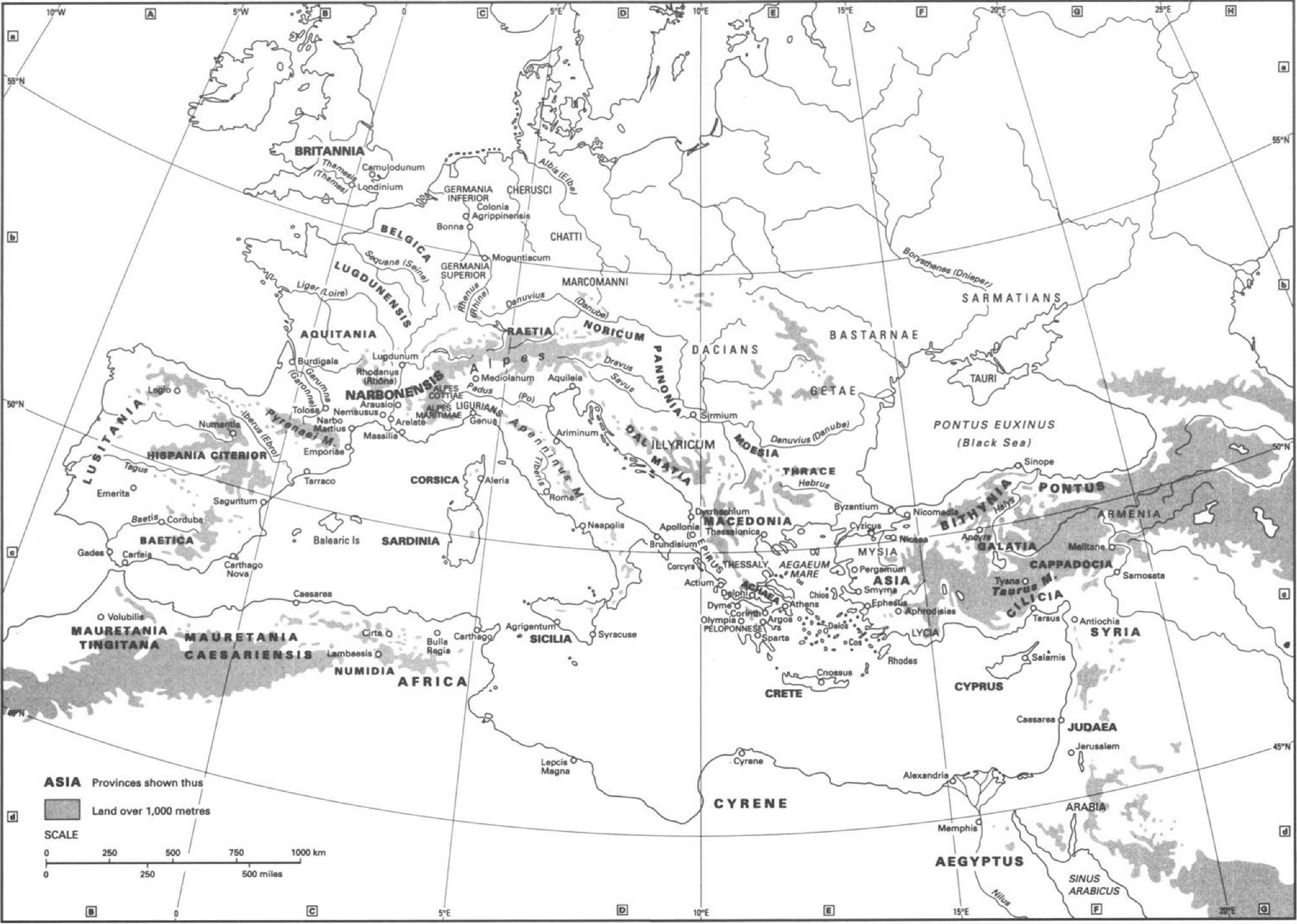

The Roman world in the time of Augustus and the Julio-Claudian Emperors page xvi

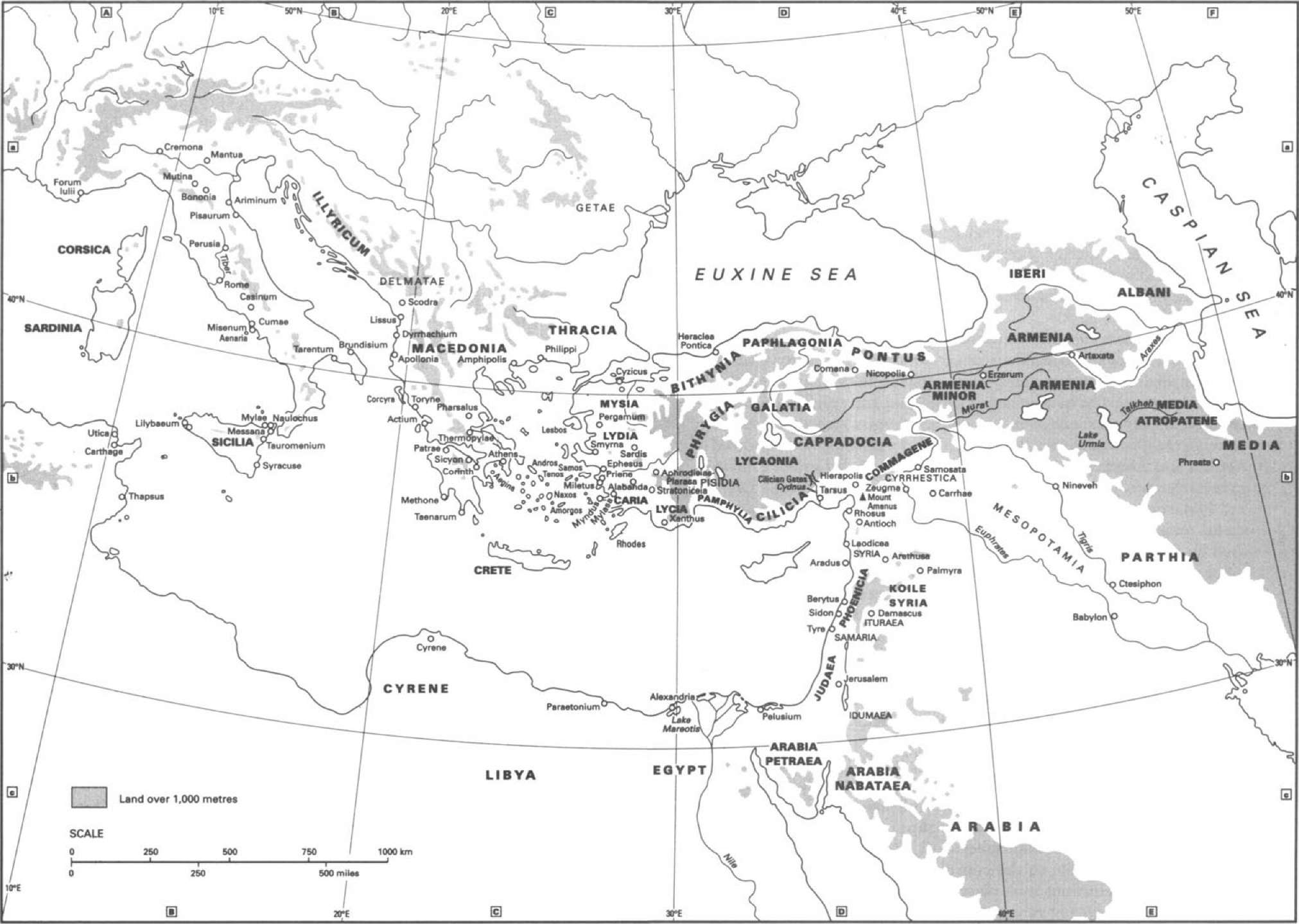

Italy and the eastern Mediterranean 2

Italy 416

Sicily 436

Sardinia and Corsica 444

Spain 450

Gaul 466

Britain as far north as the Humber 5 04

Germany 518 ro Raetia 536

Military bases, cities and settlements in the Danubian provinces 5 46

Geography and native peoples of the Danubian provinces 5 60

Africa 588

Cyrene 620

Greece and the Aegean 642

Asia Minor 660

Egypt 678

Physical geography of the Near East 704

Syria and Arabia 710

Judaea 738

The eastern Mediterranean in the first century a.d. illustrating the origins and spread of Christianity 850

TEXT-FIGURES

Actium: fleet positions at the beginning of the battle page 60

Distribution of legions, 44 в.с. 374

Rodgen, Germany: ground-plan of Augustan supply base 380

Distribution of legions, a.d. 14 386

Vetera (Xanten), Germany: ground-plan of a double

legionary fortress, Neronian date 390

Valkenburg, Holland: fort-plan, c. a.d. 40 392

Distribution of legions, a.d. 23 394

The geography of Gaul according to Strabo 467

Autun: town-plan 494 10 Sketch map of Rome 786

TABLES

New senatorial posts within Rome and Italy page 338

Provinces and governors at the end of the Julio-Claudian period 369

The legions of the early Empire 388

STEMMATA

I Descendants of Augustus and Livia page 990

II Desendants of Augustus' sister Octavia and Mark Antony 991

The family of Marcus Licinius Crassus Frugi 992

Eastern clients of Antonia, Caligula and Claudius 993 V Principal members of the Herodian family 994

Map i. The Roman world in the time of Augustus and the Julio-Claudian emperors,

PREFACE

The period covered in this volume begins a year and a half after the death of Iulius Caesar and closes at the end of a.d. 69, more than a year after the death of Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudian emperors. His successors, Galba, Otho and Vitellius had ruled briefly and disappeared from the scene, leaving Vespasian as the sole claimant to the throne of empire. This was a period which witnessed the most profound transformation in the political configuration of the res publico. In the decade after Caesar's death constitutional power was held by Caesar's heir Octavian, Antony and Lepidus as tresviri ret publicae constituendae. Our narrative takes as its starting-point 27 November 43 b.c., the day on which the Lex Titia legalized the triumviral arrangement, a few days before the death of Cicero, which was taken as a terminal point by the editors of the new edition of Volume ix. By 27 в.с, five years after the expiry of the triumviral powers, Octavian had emerged as princeps and Augustus, and in the course of the next forty years he gradually fashioned what was, in all essentials, a monarchical and dynastic rule which, although passed from one dynasty to another, was to undergo no radical change until the end of the third century of our era.

If Augustus was the guiding genius behind the political transformation of the res publico, his influence was hardly less important in the extension of Roman dominion in the Mediterranean lands, the Near East and north-west Europe. At no time did Rome acquire more provincial territory or more influence abroad than in the reign of the first princeps. Accretion under his successors was steady but much slower. Conquest apart, the period as a whole is one in which the prosperity resulting from the pax romana, whose foundations were laid under the Republic, can be properly documented throughout the empire.

It is probably true that there is no period in Roman history on which the views of modern scholars have been more radically transformed in the last six decades. It is therefore appropriate to indicate briefly in what respects this volume differs most significantly, in approach and coverage, from its predecessor and to justify the scheme which has been adopted, particularly in view of the fact that the new editions of the three

xix

volumes covering the period between the death of Caesar and the death of Constantine have to some extent been planned as a unity.

As far as the general scheme is concerned, we have considered it essential to have as a foundation a political narrative history of the period, especially to emphasize what was contingent and unpredictable (chs. i—6). The following chapters are more analytical and take a longer view of government and institutions (chs. 7—12), regions (chs. 13-14), social and cultural developments (chs. 15—21), although we have tried on the whole to avoid the use of an excessively broad brush. Interesting and invaluable though it was in its day, we have not been able to contemplate, for example, a counterpart to F. Oertel's chapter (1st edn ch. 13) on the 'Economic unification of the Mediterranean region'. We are conscious, however, that in the absence of such chapters something of value has been lost and we urge readers not to regard the first edition as a volume of merely antiquarian interest; the chapters of Syme on the northern frontiers (12) and Nock on religious developments (14), to name but two, still have much to offer to the historian.

The profound influence of Sir Ronald Syme's The Roman Revolution, published five years after the first edition of САН Volume x, is very evident in the following pages, as is that of his other, prosopographical and social studies which have done so much to re-write the history of the Roman aristocracy in the first century of the Empire. No one will now doubt that the historian of the Roman state in this period has to take as much account of the importance of family connexions, of patronage, of status and property relations as of constitutional or institutional history; and to see how these relations worked through the institutions of the res publico, the ordines, the army, the governmental offices and provincial society.

The influence of another twentieth-century classic, M. I. Rostovt- zeff's Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, first published in 1926, was perhaps less evident in the pages of the first edition of САН Volume x than might have been expected. That balance, it is hoped, has been redressed. Rostovtzeff's great achievement was to synthesize, as no-one had done before, the evidence of written documents, buildings, coins, sculpture, painting, artefacts and archaeology into a social and economic history of the empire under Roman rule which did not adopt a narrowly Romanocentric perspective. The sheer amount of new evidence accruing for the different regions of the empire in the last sixty years is immense. It is impossible for a single scholar to command expertise and knowledge of detail over the empire as a whole, and regional specialization is a marked feature of modern scholarship. The present volume recognizes this by incorporating chapters on each of the regions or provinces, as well as Italy, a scheme which will also be adopted in the new edition of Volume xi. As far as these surveys of the parts of the empire are concerned, the guiding principle has been that the chapters in the present volume should attempt to describe the developments which were the preconditions for the achievements, largely beneficial, of the 'High Empire', while the corresponding chapters in Volume xi will describe more statically, mutatis mutandis, the state of the different regions of the Roman world during that period.

Something must be said about the apparent omissions and idiosyncrasies. We have not thought it necessary to write an account of the sources for the period. The major literary sources (Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio, Josephus) have been very well served by recent scholarship and this period is not, from the point of view of the literary evidence, as problematical as those which follow. The range of documentary, archaeological and numismatic evidence for different topics and regions has been thought best left to individual contributors to summarize as they considered appropriate.

The presence in this volume of a chapter on the unification of Italy might be thought an oddity. Its inclusion here was a decision taken in consultation with the editors of the new edition of Volume ix, on the ground that the Augustan period is a good standpoint from which to consider a process which cannot really be considered complete before that, and perhaps not fully complete even by the Augustan age. Two of the chapters (those on Egypt and on the development of Roman law) will have counterparts in Volume xii (a.d. 193-337), but not in Volume xi; in both cases the accounts given here are intended to be generally valid for the first two centuries a.d. The treatment of Judaea and of the origins of Christianity posed difficulties of organization and articulation, given the extensive overlap of subject-matter. We nevertheless decided to invite different scholars to write these sections and to juxtapose them. It still seems surprising that the first edition of this volume contains no account of the origins and early growth of Christianity, a phenomenon which is, from the point of view of the subsequent development of civilization, surely the most important single feature of our period. Some degree of overlap with other standard works of reference is inevitable. We have, however, deliberately tried to avoid this in the case of literature by including a chapter which is intended as a history of literary activity in its social context, rather than a history of the literature of the period as such, which can be found in The Cambridge History of Classical Literature, Vols, i and 11.

Each contributor was asked, as far as possible, to provide an account of his or her subject which summarizes the present state of knowledge and (in so far as it exists) orthodoxy, indicating points at which a different view is adopted. It would have been impossible and undesirable to demand uniformity of perspective and the individual chapters, as is proper, reflect a rich variety of approach and viewpoint, Likewise, we have not insisted on uniformity of practice in the use of footnotes, although contributors were asked to avoid long and discursive notes as far as possible. We can only repeat the statement of the editors in their preface to Vol. viii, that the variations reflect the different requirements of the contributors and their subject-material. It will be noted that the bibliographies are much more extensive and complex than in earlier volumes of The Cambridge Ancient History; again a reflection of the greater volume of important work which has been produced on this period in recent years. Most authors have included in the bibliographies, which are keyed by coded references, all, or most, of the secondary works cited in their chapters; others have included in the footnotes some reference to books, articles and, particularly, publications of primary sources which were not considered of sufficient general relevance to be included in the bibliographies. We have let these stand.

Most of the chapters in this volume were written between 1983 and 1988 and we are conscious of the fact that the delay between composition and publication has been much longer than we would have wished. The editors themselves must bear a share of the responsibility for this. The checking of notes and bibliographies, the process of getting typescripts ready for the press has too often been perforce relegated because of the pressure of other commitments. Contributors have, nonetheless, been given the opportunity to update their bibliographies and we hope that they still have confidence in what they wrote.

There are various debts which it is a pleasure to acknowledge. Professor John Crook was involved in the planning of this volume and we are much indebted to his erudition, sagacity and common sense. We very much regret that he did not feel able to maintain his involvement in the editorial process and we are the poorer for it. For the speedy and efficient translation of chapters 14c, 14d and 20 we are indebted, respectively, to Dr G. D. Woolf, Dr J.-P. Wild (who also provided valuable bibliographical guidance) and Edward Champlin. Mr Michael Sharp, of Corpus Christi College, Oxford and Mr Nigel Hope rendered meticulous and much-appreciated assistance with the bibliographies. David Cox drew the maps; the index was compiled by Barbara Hird.

To Pauline Hire and to others at Cambridge University Press involved in the supervision and production of this volume, we offer thanks for patience, good humour and ready assistance.

A.K.B E.J.С A.W.L

CHAPTER 1 THE TRIUMVIRAL PERIOD

CHRISTOPHER PELLING

i. the triumvirate

On 27 November 43, the Lex Titia initiated the period of absolute rule at Rome. Antony, Lepidus and Octavian were charged with 'restoring the state', triumviri rei publicae constituendae\ but they were empowered to make or annul laws without consulting Senate or people, to exercise jurisdiction without any right of appeal, and to nominate magistrates of their choice; and they carved the world into three portions, Cisalpine and Further Gaul for Antony, Narbonensis and Spain for Lepidus, Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica for Octavian. In effect, the three were rulers. Soon there would be two, then one; the Republic was already dead.

Not that, at the time, the permanence of the change could be clear. As Tacitus brings out in the first sentence of the Annals, the roots of absolute power were firmly grounded in the Republic itself: there had been phases of despotism before - Sulla and Caesar, and in some ways Pompey too — and they had passed; the cause of Brutus and Cassius in the East was not at all hopeless. But what was clear was that history and politics had changed, and were changing still. The triumviral period was to be one of the great men feeling their way, unclear how far (for instance) a legion's loyalty could simply be bought, whether the propertied classes or the discontented poor of Rome and Italy could be harnessed as a genuine source of strength, how influential the old families and their patronage remained. At the beginning, there was a case for a quinquevirate, for Plancus and Pollio had played no less crucial a role than Lepidus in the manoeuvrings of mid-43. But Lepidus was included, Plancus and Pollio were not; and Lepidus owed that less to his army than to his clan and connexions. In 43 those seemed to matter; a few years later they were irrelevant, and so was he. Money too was a new, incalculable factor. In 44-43 the promises made to the troops reached new heights; and there was certainly money around — money of Caesar himself; money from the dead dictator's friends, men like Balbus and Matius; money that would be minted in plenty throughout the Roman world — no wonder that so many hoards from the period have been found, some of them vast.1 But would that money ever find its way to the

1 Crawford 1969(8 318) 117-31, 198) (в 320) 252.

i

Map г. Italy and the eastern Mediterranean,

legionaries? They did not know; no one knew. The role of propaganda was also changing. Cicero had been one master of the craft — we should not, for instance, assume that the Philippics were simply aimed at a senatorial audience; they would have force when read in the camps and market-places of Italy. But what constituency was worth making the propagandist's target? The armies, certainly: they were a priority in 4443. But what of the Italians in the municipalities? Could they be won, and would they be decisive? Increasingly, the propaganda in the thirties turned in their direction, and they were duly won for Octavian. But was he wise to make them his priority — did they matter much in the final war? One may doubt it, though they certainly mattered in the ensuing peace. But it was that sort of time. No one knew what sources of strength could be found, or how they would count. The one thing that stood out was that the rules were new.

The difference is even harder for us to gauge than for contemporaries, simply because of our source-material. No longer do we have Cicero's speeches, dialogues and correspondence to illuminate events; instead we have only the sparsest of contemporary literary and epigraphic material, and have to rely on much later narratives - Appian, who took the story down to the death of Sextus Pompeius in his extant Civil Wars (he told of Actium and Alexandria in his lost Egyptian History)-, Cassius Dio, who gave a relatively full account of the triumviral period in Books xlvii-l; and Plutarch's fine Lives of Brutus and Antony. Suetonius too had some useful material in his Augustur, so does Josephus. The source-material used by these authors is seldom clear, though Asinius Pollio evidently influenced the tradition considerably, and so did Livy and the colourful Q. Dellius; but all the later authors may well have used other, more recherche material. Still, all are often demonstrably inaccurate, and there is indeed a heavy element of fiction throughout the tradition. Octavian's contemporary propaganda, doubtless repeated and reinforced in his Autobiography when it appeared during the twenties, spread stories of the excesses and outrages of Antony and Cleopatra; then the later authors, especially Plutarch, elaborated with romance, evincing sometimes more sympathy for the lovers, but scarcely more accuracy. And all these authors naturally concentrated on the principals themselves - Brutus, Cassius, Octavian, Sextus, Antony and Cleopatra. We are given very little idea of what everyday political life in Rome was like, how far the presence of these great men smothered routine activity and debate in the Senate, the courts, the assemblies and the streets. The triumvirs controlled appointments to the consulship and to many of the lower offices, but some elections took place as well; we just do not know how many, or how fiercely and genuinely they were contested.2 The plebs and

2 Cf. Frei-Stolba 1967 (c 92) 80-6; Millar 1973 (c 175) 51-3.

the Italian cities did not always take the triumvirs' decisions supinely; but we do not know how often or how effectively the triumvirs were opposed in the Senate, or how much freedom of speech and action senators asserted in particular areas. We hear little or nothing of the equiter. we cannot be sure that they were so passive or uninfluential. We no longer hear of showpiece political trials; it does not follow that they never happened. Everything in the sources is painted so starkly, in terms of the actions and ambitions of the great persons themselves. We have moved from colour into black and white.

ii. philippi, 42 b.c.

At Rome the year 42 began momentously. Iulius Caesar was consecrated as a god.[1] Roman generals were used to divine acclamations in the East, and divine honours had been paid in plenty to Caesar during his lifetime: but a formal decree of this kind was still different. Octavian might now style himself divifilius if he chose;4 and the implications for his prestige were, like so much else, incalculable. But a more immediate concern was the campaign against Brutus and Cassius in the East, a war of vengeance which the consecration invested with a new solemnity. Antony and Octavian were to share the command. The triumvirs now controlled forty-three legions: probably forty were detailed to serve in the East, though only twenty-one or twenty-two actually took part in the campaign and only nineteen fought at Philippi.[2] Lepidus would remain in control of Italy, but here too Antony's influence would be strong: for two of his partisans were also to stay, Calenus in Italy and Pollio in the Cisalpina, both with strong armies.

A preliminary force of eight triumviral legions, under C. Norbanus and L. Decidius Saxa, crossed the Adriatic early in the year: but the Liberators' fleets soon began to operate in the Adriatic, eventually some i jo ships under L. Staius Murcus and Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus, and it would evidently be difficult to transport the main army. A further uncertainty was furnished by the growing naval power of Sextus Pompeius. His role in the politics of 44-43 had been slight, but he had appeared on the proscription list, and now it must have seemed inevitable that he would be forced into the Liberators' camp. By early 42 he had established himself in control of Sicily, his fleet was growing formidable, and he was already serving as a refuge for the disaffected, fearful and destitute of all classes. Many of the proscribed now swelled his strength. But Octavian sent Salvidienus Rufus to attack Sextus' fleet, and a great but indecisive battle ensued outside the Straits of Messana. After this Sextus' contribution was slight, and the Liberators gained very little benefit from potentially so valuable an ally. By summer, the main triumviral army managed to force its crossing.

In Macedonia the news of the proscriptions and Cicero's death had sealed C. Antonius' fate: he was at last executed, probably on Brutus' orders.[3] Brutus himself had been active in Greece, Macedonia, Thrace and even Asia through the second half of 43, raising and training troops and securing allies and funds. He finally began his march to meet Cassius perhaps in the late summer, more likely not until early 4г.[4] Cassius himself was delayed far away in the East till late in 43: even after Dolabella's defeat in July, there was still trouble to clear up — in Tarsus, for instance, where he imposed a fine of 1,5 00 talents, and in Cappadocia, where unrest persisted until Cassius' agents murdered the king Ariobar- zanes and seized his treasure in summer 42. The troubles were doubtless exacerbated by the harshness of Cassius' exactions, but the wealth of the East was potentially the Liberators' greatest asset (extended though they were to support their army, the triumvirs' position was even worse), and Cassius naturally wanted to exploit it to the full. It was perhaps not until winter, when the triumvirs had united and there were already fears that the first of their troops were crossing to Greece, that Cassius began the long westward march.[5] He and Brutus met in Smyrna in the spring of 42. Between them they controlled probably twenty-one legions, of which nineteen fought in the decisive campaign.[6]

The story went that they differed over strategy, Brutus wishing to return quickly to Macedonia, Cassius insisting that they first needed to secure their rear by moving against Rhodes and the cities of Lycia.[7]Cassius had his reasons, of course. Lycia and Rhodes were temptingly wealthy, and there were even some strategic arguments for delay: with the Liberators dominating the sea, the triumviral armies might be destroyed by simple lack of supplies. But still he was surely wrong. Philippi is a very long way east, and the battles there were fought very late in the year. The friendly states in Macedonia and northern Greece, who had welcomed Brutus with some spontaneity the previous year and whose accession Cicero had so warmly acclaimed in the Tenth Philippic, were by then lost, and their wealth and crops were giving vital support to the triumvirs, not the Liberators. Rhodes and Lycia had strong navies, but Cassius and Brutus had very litde to fear from them: the Liberators would dominate the sea in any case. It would surely have been better to move west quickly, provide better bases for their fleet in the Adriatic, and seek to isolate the advanced force on the west coast of Greece — to play the 48 campaign over again, in fact; and those eight unsupported legions of Norbanus and Saxa would have been hopelessly outmatched. The Liberators' brutal treatment of Rhodes and Lycia did nothing for their posthumous moral reputation. Perhaps it also cost them the war.

Cassius moved against Rhodes, Brutus against Lycia, and both won swift, total victories: in particular, the appalling scenes of slaughter and mass suicide in Lycian Xanthus became famous. Perhaps 8,500 talents were extorted from Rhodes; the figure of 15 о talents for Lycia is hard to believe.11 The other peoples of Asia were ordered to pay the massive sum of ten years' tribute, although the region had already been squeezed dreadfully in the preceding years. Some of the money was doubtless paid direct to the legionaries, some more was kept back for further distributions during the decisive campaign: in the event the army stayed notably loyal, though this was doubtless not only for crude material reasons. The campaigns were rapid, but it was still June or July before Brutus and Cassius met again at Sardis, and began the northward march to the Hellespont, which they crossed in August.

Norbanus and Saxa had marched across Macedonia unopposed, and took up a position east of Philippi, trying to block the narrow passes; but the much larger force of Brutus and Cassius outflanked them, and reached Philippi at the beginning of September. Norbanus and Saxa fell back upon Amphipolis, where they linked with the main army under Antony: Octavian, weakened by illness, was following some way behind. Brutus and Cassius then occupied a strong position across the Via Egnatia. Within a few days Antony came up and boldly camped only a mile distant, in a much weaker position in the plain. Octavian, still sick, joined him ten days later. Despite the strength of their position, the Liberators at first sought to avoid a battle. They controlled the sea, the triumvirs' land communications to Macedonia and Thessaly were exposed, and Antony and Octavian would find it difficult to maintain a long campaign. But Antony's deft operations and earthworks soon began to threaten the Liberators' left, and Cassius and Brutus decided to

11 Plut. Brut. 32.4.

accept battle. There was not much difference in strength between the two sides: the triumviral legions had perhaps nearly 100,000 infantry, the Liberators something over 70,000; but the Liberators were the stronger in cavalry, with 20,000 against 13,000.[8]

Cassius commanded the left, Brutus the right, facing Antony and Octavian respectively. The battle began on Cassius' wing, as Antony stormed one of his fortifications. Then Brutus' troops charged, apparently without orders; but they were highly successful, cutting to pieces three of Octavian's legions and even capturing the enemy camp. Cassius fared much worse: Antony's personal gallantry played an important part, it seems, and he in turn captured Cassius' camp. In the dust and the confusion Cassius despaired too soon, and in ignorance of Brutus' victory he killed himself. So ended this first battle of Philippi (early October 42). On the same day (or so it was said) the Liberators won a great naval victory in the Adriatic, as Murcus and Ahenobarbus destroyed two legions of triumviral reinforcements.

Then there were three weeks of inaction. The first battle had done nothing to ease the triumviral problems of supply, and Antony was forced to detach a whole legion to march to Greece for provisions. But Brutus was under pressure from his own army to fight again; he was a less respected general than Cassius, and after the first battle he feared desertions; and he also soon found his own line of supplies from the sea threatened, for Antony and Octavian occupied new positions in the south. He felt forced to accept a second battle (23 October). His own wing may again have won some success, but eventually all his lines broke. The carnage was very great; and Brutus too took his own life. With him died the republican cause. Several of the surviving nobles also killed themselves, some were executed, others obtained pardon; a few fled to Murcus, Ahenobarbus, or Sextus Pompeius. Most of the troops came over to the triumvirs.[9]

Antony had long been known as a military man, but until now his record was not especially lustrous. His wing had played little part at Pharsalus, he had been absent from most of Caesar's other battles, and the outcome at Mutina had been shameful. All that was now erased. Octavian had given little to this victory; he had indeed been absent from the first battle — hiding in the marsh, and not even his friends could deny it.14 Before the fighting the forces had appeared equally matched: it was Antony's operations that forced the battles, his valour that won the day. He took the glory and the prestige. Now and for years to come, the world saw Antony as the victor of Philippi.

iii. the east, 42-40 b.c.

Antony's strength was reflected in the new division of responsibility and power. His task would be the organization of the East; he was also to retain Further Gaul, and take Narbonensis from Lepidus; he would lose only the Cisalpina, which was to become part of Italy. Italy itself was nominally left out of the reckoning, but Octavian was to be the man on the spot, with the arduous and unpopular task of settling the veterans in the Italian cities. He was also to carry on the war against Sextus Pompeius; he would retain Sardinia; and he too was to gain at Lepidus' expense, taking from him both provinces of Spain. Lepidus himself would be allowed only Africa; and there was some doubt even about that.15 Already, clearly, he was falling behind his colleagues. Antony was also to keep the greater part of the legions. A large number of the troops in the East had served their time, and were to be demobilized; the rest, including those who had just come over from Brutus and Cassius, were to be re-formed into eleven legions. Antony was to take six of these, Octavian five; he was also to lend Antony a further two. The position concerning the western legions is more obscure, but there too Antony's marshals seem to have controlled about as many legions as Octavian.[10]Antony promised that Calenus would transfer to Octavian two legions in Italy to compensate for the two he was now borrowing: but such promises readily foundered. The legions stayed with Calenus.

In Antony's lifetime two generals had successfully invaded Italy from their provinces, Sulla from the East and Caesar from Gaul. Both Gaul and the East would now fall to Antony. The menace was clear. The case of Gaul is particularly interesting. So much of the fighting and diplomacy of the last two years had been, in one way or another, a struggle for Gaul: and the province's strategic importance was very clear.[11] With hindsight, we always associate Antony with the East; Octavian's propaganda was to make great play with his oriental degeneracy. But nothing suggests that Antony yet planned any extended stay in the East. Naturally, he eyed its riches and prestige; he might of course have to play Sulla over again; but it was just as likely that he would return peaceably, as Pompey had returned in the sixties, to new power and authority in the West. In that case, and in the likely event of the triumvirs eventually falling out, Gaul would prove vital. Its governor would be Calenus, with eleven legions: Antony could rely on him. And, even if the Cisalpina were technically part of Italy, that too would not be out of Antony's control: Pollio was to be there, and he too had veterans under his command. The trusty Ventidius would also be active in the West, perhaps in Gaul, perhaps in Italy.[12] In the event Antony's possession of Gaul came to nothing, for Octavian took it over bloodlessly on Calenus' death in 40. It was that important historical accident that would turn Antony decisively towards the East. But, for the moment, possession of Gaul kept all his important options free.

The East came first. Its regulation would be a massive task, but a rewarding one; and it also offered the possibility of a war against Parthia. King Orodes had helped Cassius and Brutus,[13] and vengeance was in order; indeed, the republican commander Labienus was still at the Parthian court. No one yet knew what to expect of that; but, whether or not Parthia attacked Roman Asia Minor again, a Roman general could always attack Parthia, avenging Crassus' defeat, tickling the Roman imagination and enhancing his own prestige. He might even appear a second Alexander, if all went well: that always had a particular appeal to Roman fancy.

Antony spent the winter of 42/1 in Greece, where he made a parade of his philhellenism.[14] In spring 41 he crossed to Asia; it seems that he visited Bithynia, and presumably Pontus too, before returning to the Aegean coast.[15] At Ephesus, effectively Asia's capital, he was greeted as a god — such acclamations were by now almost routine in the East;[16] but exuberance soon turned sour, as Antony addressed representatives of the Asian cities and announced his financial demands. Yet again, the East found it had to fund both sides in a Roman civil war: and this time vast sums were needed to satisfy the legions — perhaps 15 0,000 talents if all the promised rewards were to be paid.[17] That was well beyond even the East's resources, especially after the exactions of Dolabella, then Cassius and Brutus. Antony eventually demanded nine years' tribute from Asia, to be paid over two years;[18] and he would be fortunate if the province could manage that. Asia's normal tribute was probably less than 2,000 talents a year.[19] Even allowing for contributions from the other eastern provinces and for extra sums from client kings and free cities,26 Antony could scarcely hope for more than 20,000 talents, the amount which Sulla raised in a similar levy after the Mithridatic War. And not all of that could be spent on rewards. There were the running costs of Antony's army and staff; there was a fleet to build, for Murcus, Ahenobarbus and Sextus were still worryingly strong;27 there were preparations to be made for war with Parthia. The troops were still calling for their rewards a year later.28

Yet there was generosity, too, in Antony's dispensations. He pardoned virtually all the supporters of Brutus and Cassius, excepting only those who had participated in the tyrannicide itself; that was more merciful than many expected.29 The states that had suffered worst from the Liberators, Lycia and Rhodes, were excused from the levies; later he extended a similar clemency to Laodicea and Tarsus. Rhodes was indeed given some new territory — Andros, Tenos, Naxos and Myndus.30 From mainland Greece the Athenians soon sent an embassy, and they too were favoured: they gained control of several islands, including Aegina. Antony was clearly favouring the great cultural centres. Such ostentatious philhellenism doubtless came naturally to him, but it might also prove politically valuable, and not merely in certain circles at Rome: in the East itself it had become fashionable for monarchs to show their enthusiasm for the great cities of the past by benefactions, and they might applaud Antony when he showed similar indulgence. It was also probably now, and in line with the same cultural policy, that he granted various privileges and immunities to 'the worldwide association of victors in the festival games' - an association which, it seems, included artists and poets as well as athletes.31 Antony spent the rest of summer 41 in touring the eastern provinces, imposing further levies and beginning to reorganize the administration after the disruption of the war: Antony himself could refer to Asia's need to recover from its 'great illness'.32 The range and deftness of his dispositions were eventually to be peculiarly impressive, but as yet there was only time for a few piecemeal measures. The highest priority had to be the regions furthest to the east, for they would be vital if it came to war with Parthia. Syria was particularly sensitive. Its cities had greeted Cassius with enthusiasm, and he had supported tyrants who were (it seems) disturbingly sympathetic to Parthia:33 most of them clearly had to go. So, probably, did Marion, tyrant of Tyre.34 Herod of Judaea was similarly compromised by his

App. BCiv. v. 55.230. 28 Dio xLvni.30.2.

Dio XLvm.24.6 — perhaps guesswork, but as often intelligent.

PossiblyAmorgustoo:cf./Gxii 5.58 and xii Jo/i/i. p. 102no. 38, withSchmitt i957(e872) 186 n. 2; contra, Fraser and Bean 1954 (e 828) 163 n. 3.

EJ2 300, RDCE 57; but it is possible that these privileges were not granted till 32: see RDGE adloc. and Millar 1973 (c 175) 55, 1977 (a 59) 4)6. Cf. also the triumviral inscription from Ephesus concerning travel-privileges for 'teachers, sophists and doctors': Knibbe 1981 (c 138).

52 In his letter to the Jews, Joseph. A] xiv.j 12.

According to App. BCiv. v.10.39,42> 'bey fled to the Parthian king after their deposition: not improbable, cf. Buchheim i960 (c 49) 27.

Tyrant in 42 when he invaded Galilee (Joseph. BJ 1.238-9, AJ xiv.298); but Antony's letter in 41 (next note) is addressed only to the magistrates and council (AJ xiv.314). Cf. Weinstock RE xiv 1803.

support for Cassius, but here Antony knew better than to play into the hands of the anti-Roman nobility. Herod and his brother Phasael were recognized as 'tetrarchs'; Judaea even recovered some territory it had lost to the Phoenician cities.35 And Egypt, with all its wealth, would inevitably be important. Momentously, Antony summoned its queen to meet him in Cilicia.

Plutarch and Shakespeare have immortalized the famous meeting on the Cydnus - the marvellous gilded barge, the purple sails, Cleopatra's display as Aphrodite; and, delightfully, much of the description is likely to be true.36 The queen's relations with Antony swiftly became more than diplomatic: their twins were born only a year later; and he spent the winter of 41-40 with her in Alexandria - a winter of careless frolics, so the story later went.37 But there were bloody elements too. Cleopatra was still insecure on her throne, threatened by her sister Arsinoe; Antony had Arsinoe dragged from sanctuary in Ephesus and murdered. Tyre had to surrender Serapion, the admiral who had betrayed Cleopatra's fleet to Cassius and Brutus; Arados was forced to give up a pretender to the Egyptian throne. Later writers naturally dwelt on the infatuation which forced Antony to such gruesomeness; but he could reasonably feel that it made political sense to favour Cleopatra in this way. He was regularly to favour strong, talented rulers, people like Polemo in Pontus or Herod in Judaea, people on whom he felt he could rely; and he could certainly rely on Cleopatra. Any infatuation was clearly under control; at least, for the present. In the spring of 40 he left her, and did not return for nearly four years.

For by the spring Alexandria was no place for Antony. Worrying news had been arriving about disorder in Italy, and now there was a more immediate threat in Asia Minor itself. During 41 Antony had probably been preparing for an offensive war against Parthia - by the end of the season he had indeed taken the border town of Palmyra in Syria. It seems that Parthia, naturally enough, responded by gathering a force in Mesopotamia to meet the evident threat. But, after Antony had departed to Alexandria for the winter, the Parthians decided to seize the moment and attack Roman Asia Minor themselves;38 and, far from waging a glorious campaign of vengeance, Antony had to hasten to put up what defence he could. The Parthian command was shared between the crown-prince Pacorus and Q. Labienus himself, son of that famous commander of Caesar who went over to Pompey at the beginning of the civil war. Brutus and Cassius had sent him to seek aid from Orodes, and

35 Tyre, Sidon, Antioch and Aradus: cf. Joseph. A] xiv.304-23, quoting verbatim Antony's letters to the Jews and to Tyre. * Plut. Ant. 26, with Pelling 1988 (в 138) aJloc.

Plut. Ant. 28-9; cf. App. BCiv. v.i 1.43-4.

Dio XLviii. 24.6-8, explicidy placing the decision after Labienus had heard of Antony's 'departure to Egypt'.

he had still been at the Parthian court when news of Philippi arrived. Wisely, he stayed where he was; and we need not doubt that he played an important role in persuading Orodes to attack now, when he rightly gauged that Antony might be vulnerable. It is easy but unfair to see Labienus as a latter-day Coriolanus, a renegade turning against his country through pique. In fact, republicans had long since been playing for Parthian support. Pompey had sought an alliance with Orodes against Caesar;39 a few years later the Parthians had been helping the republican troops of Q. Caecilius Bassus against Caesarians in Syria;40 Parthian contingents had even fought in the Philippi campaign.41 Over in the West, men could equally toy with the notion of exploiting Gallic nobles in a Roman civil war; might they not show themselves worthier champions of liberty than the Romans themselves?42 Doubtless there was hypocrisy in such proud phrases; but it was not confined to Labienus. He was indeed largely welcomed by the Roman garrisons in Syria,43 and apparently in Asia too.44

The campaign began in the early spring of 40. Labienus - now styling himself Q. LABIENUS PARTHICUS IMPERATOR45 - and Pacorus swiftly overran Syria: it had fallen before Antony could even reach Tyre, then he anyway found it necessary to sail west to Italy. The Parthian successes continued. Pacorus took Palestine, and installed the pretender Antigonus on the throne; Phasael was taken captive, then contrived to kill himself; Herod fled to Rome. Meanwhile Labienus swept through Cilicia and onward to the Ionian coast. The Carian cities of Alabanda and Mylasa fell to him, and Stratoniceia and Aphrodisias clearly suffered terribly;46 so perhaps did Miletus;47 Lydia too was overrun.48 Labienus met no effective resistance till 39, and by then northern Asia Minor had also felt his power; his agents were raising money even from Bithynia.49

And Antony could do nothing about it; for by now the news from Italy was even more alarming.

iv. perusia, 4i-4o b.c.

Even before Philippi, eighteen Italian cities had been marked down to provide land for the triumvirs' veterans; and it fell to Octavian to organize the settlement. It was a hateful task, involving widespread confiscation and intense misery for the dispossessed, who received no compensation: a hideous climax to a half-century of rural violence and horror. Virgil's Eclogues, especially the first and ninth, leave a moving imprint of a small farmer's suffering. But the tiniest holdings were eventually exempted, and so, often, were the largest: in particular, senators' estates were excluded; and, as in most of the cities some veteres possessores managed to hold on to their property, one may assume that the most influential local citizens often secured exemption. That left a great range of the middling well-off who were dispossessed, some who farmed at not much more than subsistence level, others who were quite wealthy people with slaves and fine villas. Their holdings were replaced by the standardized chequer-boards of the new allotments, usually it seems of up to 50 iugera for an ordinary soldier and perhaps 100 iugera or more for an officer. Eighteen cities turned out to be too few, and perhaps as many as forty were eventually involved. The most usual method was to extend the confiscations into the territory of a neighbouring town, as, famously, into Virgil's Mantua when nearby Cremona could offer too little land: 'Mantua, vae miserae nimium vicina Cremonae'.[20]

It all came at a time when Italy was anyway torn by famine, as Sextus grew stronger and his fleet prevented the vital corn-ships from coming to port. (Ahenobarbus' and Murcus' ships were doing the same, though still acting independently of Sextus.) Unsurprisingly there were violent protests, from landowners, from the magnates in the country-towns, from the urban plebs, even from the veterans themselves: they were becoming anxious at the slow pace of the settlement, and also concerned to protect the holdings of their own families and those of their dead comrades. There was soon rioting throughout Italy, with clashes between the new colonists and those they threatened; armed bands were roving the countryside. It was to take years for the disorder to settle.51 Antony's brother L. Antonius was consul in 41, and far from helping Octavian he served as a rallying-point for the discontented. Initially he was perhaps opposed by Antony's wife Fulvia,[21] but she soon lent her full support. To the dispossessed they urged resistance in the name of liberty and the established laws.[22] Perhaps we need not take their own commitment to freedom too seriously,[23] but it is interesting that they thought the slogans worth airing; and, indeed, old republicans were regularly to find Antony's cause more appealing than Octavian's.55 The veterans were encouraged to believe that all would be well once Antony returned: their debt of duty to the great man became another slogan. L. Antonius even, rather absurdly, took the cognomen Pietas.[24] There were charges, too, that Octavian was favouring his own veterans above Antony's in the distributions, and demands that the Antonian settlements should be supervised by Antony's own partisans.[25] The charges seem to have been conspicuously untrue: the Antonian colonies turned out to be the more numerous and the more strategically based.[26] But Octavian still felt it best to accede to the demand for Antonian commissioners, whatever might have been said at Philippi about his freedom to organize the settlement as he chose. That agreement of Philippi was indeed looking increasingly frail. The other Antonian marshals were less blatant than the consul Antonius, but they too were adding to the tension. Calenus never gave the promised two legions; Pollio blocked the route of Salvidienus Rufus as he tried to march with six legions to Spain.

At first Antony, far off in the East, thought it best to send no clear response, though he certainly knew what was going on. Everyone made sure of that, with Octavian sending confidential messengers and the colonies too taking care that their plight was known.[27] He had probably not planned or encouraged the troubles himself: it was a nice judgment whether he really stood to gain more than lose by the exchanges. Now he might naturally relish Octavian's embarrassment, but he could hardly come out openly against him; Octavian after all was merely pursuing his part of a shared bargain. Besides, Antony could not let his own veterans down, or allow Octavian to win more of their gratitude. He might need them again soon. A studied vagueness about his own views would indeed make sense, allowing him to exploit the outcome whichever way it went: there were times in antiquity when the slowness and unreliability of communications could be useful. But the consequences were very unfortunate. Unsure of his wishes, confused by various reports and missives,60 his supporters in Italy were bewildered. Just as on several occasions in 44 and 4 j, army officers and the veterans themselves pressed for a compromise,61 and so did two senatorial embassies to L. Antonius; but in the summer of 41 it came to war.

L. Antonius occupied Rome with an army, then marched north, hoping to link with Pollio and Ventidius. Operations in Etruria were complex and confused, but in the autumn L. Antonius was forced into Perusia and besieged by Octavian, Agrippa and Salvidienus Rufus. Still unsure of Antony's wishes, Pollio and Ventidius decided not to intervene. Plancus, arriving from the south, made the same choice. That made thirteen Antonian legions which stood by, inactive; L. Antonius himself had no more than eight.62 The siege wore on, bitterly. Both sides occupied idle moments by adding obscene graffiti to their sling-bullets, musing on Antonius' baldness, Octavian's backside, and Fulvia's private parts; Octavian himself wrote some peculiarly rude elegiacs at Fulvia's expense.63 The city eventually fell, amid scenes of dreadful bloodshed, in the early spring of 40. L. Antonius' veterans were spared: interestingly, their old comrades on Octavian's side interceded for them.64 Antonius himself was received honourably by Octavian, and indeed was sent to govern Spain (he died soon afterwards). Fulvia was allowed to flee to Athens. The ordinary dwellers of Perusia were not so fortunate. All the town-councillors except one were killed. Octavian's enemies soon elaborated the story, with talk of a human sacrifice of 300 senators and knights at the altar of Divus lulius\bb but the unembroidered truth was horrifying enough. The city itself was given over to Octavian's troops to plunder, and it burnt to the ground. A few years later the Umbrian Propertius chose to conclude his first book of witty love elegies with a disquieting and unexpected coda, two short stark poems on the suffering of the Perusine war (1.21, 22).

If a generation before Pompey had seemed an adulescentulus carnufex, Octavian was surely emerging as his equal. But he had not let the veterans down, and he had emphatically established his control of Italy. Soon, indeed, he would seem master of the entire West, when Calenus died in the summer of 40 and he swiftly occupied Gaul as well. Calenus' legions seem to have come over fairly readily, and so did two legions of Plancus in Italy. Perhaps they felt Octavian was now the more reliable champion of their interests.66

Cf. App. BCiv. v. 29.11 2 (a letter which Appian sensed might have been forged), 31.120.

App. BCiv. v.20.79-23.94.

App. BCiv. v.50.208, cf. 24.95, 29.114-30.115; Brunt 1971 (a 9) 494-6.

ILLRP 1106-18; cf. Hallett 1977 (c 109). Mart. x:.2o quotes Octavian's verses.

App. BCiv. v.46.196—47.200.

Suet. Aug. 15.1; cf. Dio XLVin.14.4: but App. BCiv. v.48.201-2 makes clear that senators and knights were spared. In general, Harris 1971 (e 55) 301—2.

Cf. Dio XLVin.20.3; Aigner 1974 (c 3) 113.

No wonder Antony was concerned. He hurried back to Italy in the midsummer of 40; and he arrived in some strength.

V. BRUNDISIUM AND MISENUM, 4O-39 B.C.

As relations had worsened, both Antony and Octavian had thought of wooing Sextus to their side. He was indeed worth wooing: Murcus had recently joined him, and Sextus' combined fleet now numbered something like 250 ships.67 Now, in the summer of 40, Octavian married Scribonia, the sister of Sextus' associate and father-in-law L. Scribonius Libo. But Sextus was always particularly distrustful of Octavian, and preferred to look to Antony: indeed, Antony's mother Iulia had fled confidently to Sextus after Perusia's fall, which may suggest that there was already some secret understanding. Sextus sent a prestigious escort, including Libo, to accompany her to Antony, and took the opportunity to offer him an alliance. Antony replied in measured but encouraging terms: if it came to war with Octavian, he would welcome Sextus as his ally; if he and Octavian made their peace, he would try to reconcile Octavian with Sextus as well. The understanding was sufficiently strong for Sextus to raid the Italian coast in Antony's support;68 and a little later he occupied Sardinia and displaced Octavian's governor M. Lurius.

Octavian's ruthlessness in Italy, and perhaps his uncompromising response to L. Antonius' proclamations of freedom, had a further sequel. Domitius Ahenobarbus was also persuaded by the consul Pollio to join Antony, and his seventy ships joined Antony's two hundred as they sailed towards Brundisium. The alignments of early 43 had been paradoxically reversed. Republicans and Antony, with Sextus in the background, now stood together to confront the isolated Octavian; Brundisium might well turn out a Mutina in reverse, except that both Antony and Octavian were now much stronger. But, as in 43 but this time before serious bloodshed, Antony and Octavian were to find it prudent to come to terms.

There was some initial military activity. Brundisium, guarded by five of Octavian's legions, would not admit Antony's fleet, and was laid under siege; meanwhile Sextus was still continuing his raids on the coast. Octavian sent Agrippa to the town's aid, and himself swiftly followed; his troops were numerically superior69 but reluctant, and some of them turned back. There was some skirmishing; Antony had the better of it. But by now deputations of each army were urging compromise, and it was not at all clear that either side would fight. The two men's friends began to discuss terms, with Maecenas negotiating for Octavian, Pollio

App. BCh>. v.25.100; Veil. Pat. 11.77.3.

Dio XLvm.20.i—2, clearly dating to midsummer.. и Brunt 1971 (a 9) 497.

for Antony, and L. Cocceius Nerva as something of a neutral. Lepidus, unsurprisingly, was not represented. (He had been notably ineffectual in Italy during the Perusine War, and by now he was out of the way in Africa.) Thus was reached the Treaty of Brundisium (September 40).

The agreement closely duplicated the compact of Philippi, except for the important change that followed from Calenus' death. Octavian's occupation of Gaul was now recognized; he was also to have Illyricum. Antony was no longer simply entrusted with the organization of the East, he was also recognized as its master. The division of the world was correspondingly neater, with Antony controlling the East and Octavian the West: Scodra in Illyria was given unprecedented prominence as the dividing-point of the dominions. Lepidus might retain Africa, for what that was worth. Antony was to avenge Crassus by carrying through the Parthian War, Octavian to assert his claim to Sardinia and Sicily by expelling Sextus — unless (an interesting qualification) Sextus came to some agreement. There was also to be an amnesty for republican supporters. The consulships for the next few years were allocated; there was also a reallocation of legions, with Antony receiving some recompense for Calenus' army.[28]

This division of East and West was less clear-cut than it appeared. For instance, eastern as well as western states could address petitions to Octavian, and Octavian could answer them with authority;[29] he even sent cvtoAcu, a 'commission' (the Latin mandata), to Antony to restore loot to Ephesus.[30] But, rough though it was, the division had momentous consequences. First, Antony faced a more exclusively eastern future. If it came to war, he could no longer think of fighting the campaign of 49 over again, descending from the Alps as a new Iulius Caesar into a quavering Italy. Secondly, Octavian's position in Italy was a priceless asset. In 42 it might have seemed an embarrassment, with all those veterans to setde; but he had ridden that storm. Italy was now supposed to be shared by both men, open to each for his recruiting. But Octavian was there, Antony was not. It proved steadily more possible for Octavian to pose as the defender of Roman and Italian traditions against the monstrous portent of a degenerate Antony, declining into eastern weakness and eastern ways. The control of Italy, in 42 a sign of Octavian's inferiority, became an important element in his final success.

The new accord of Antony and Octavian was confirmed by a further bond, one which was to add richness to the latter romantic legend. Antony was now a widower, Fulvia having conveniently died in Greece. Octavia, the sober sister of Octavian, was to be his new bride. The great dynastic marriage was to seal the union of the dominions. There was no need to complicate the matter with any thoughts of Cleopatra.

Italy rejoiced at the treaty. It is probably wrong to connect Virgil's Fourth Eclogue with this: it was more likely written earlier, in the miserable days of late 41, and was designed to greet Pollio as he entered his consulship on the first day of 40. But more mundane celebration is clear enough. On 12 October the magistrates of Casinum erected a monument to mark the accord, a signum Concordiae.12, Coins too were struck in celebration, one for instance showing a head of Concordia and two hands around a caduceus (a symbol of concord) with the inscription M.ANTON.C.CAESAR.IMP.[31] Both Antony and Octavian celebrated ovationes as they entered Rome a few weeks later. But the festivities again swiftly soured. For one thing, the impoverished triumvirs again imposed unprecedented taxes.[32] Just as serious, Sextus - who could reasonably feel let down by the treaty's terms — was maintaining his pressure. There was fighting in Sardinia within a few weeks of the accord, with Octavian's general Helenus recapturing the island, then in his turn expelled by Sextus' admiral Menodorus. Sextus had by now taken over Corsica as well, and penetrated to Gaul and Africa;76 and his blockade of the Italian corn-ships was more effective than ever. By November Rome was again reduced to famine, and Antony and Octavian were confronted by violent popular riots. Both men also had troubles of their own, and the atmosphere was heavy with strain and suspicion. Antony executed his agent Manius, who had been very active in the Perusine War. Still more striking, Octavian recalled his general Salvidienus Rufus from Gaul, and had him killed. This extraordinary man had been consul designate for the following year, the first man since Pompey to be awarded a consulship before even entering the Senate: now his fall was just as abrupt. It was said that he had been plotting with Antony earlier in the year — indeed, that Antony frankly admitted it. That strains belief; but the truth is wholly elusive.77

Salvidienus' killing was prepared by the passing of the senatus consultum ultimum. The triumvirs' own extraordinary position was itself sufficient to authorize such emergency action; but, as usual with the s.c.u., it was moral rather than legal justification which was really in point. The Senate's moral backing was still worth having, and this was one of several occasions when the triumvirs paraded a certain constitutionalism. For instance, Octavia's marriage to Antony was technically difficult, for she had not completed the legal term of mourning after the death of her first husband, Marcellus: a dispensation was scrupulously secured from the Senate.[33] And Herod was to be recognized as king of Judaea: Antony and Octavian had agreed it - but the formal decision was deferred to the Senate, with Antony himself joining in the debate; a solemn procession to the Capitol followed, led by the consuls.[34] At some time during 39 the triumvirs also secured a senatorial decree to ratify all their past and future acts:[35] constitutionalism again, though of a rather quizzical kind. Like L. Antonius two years earlier, they evidently felt that traditionalist public sentiment was worth impressing.

But peace would surely impress people more. The Brundisium agreement had explicitly envisaged the possibility of coming to terms with Sextus as well. But it was not clear if Sextus himself would agree: there seems to have been some difference of view among his supporters, who were very disparate. The pirate-admiral Menodorus, we are told, pressed Sextus to continue the war, Staius Murcus and others took the opposite view; and here too the issues were fogged by suspicion, with Sextus by now deeply distrustful of Murcus. Murcus duly died, mysteriously. But Sextus still saw the force of his advice: he himself had always been realistic about his chances in a full-scale war. There was a preliminary meeting of negotiators at Aenaria in spring, 39. Scribonius Libo, once again emerging in a context of conciliation, represented Sextus. Octavian, Sextus and Antony then met at Cape Misenum in full summer, perhaps as late as August,[36] and terms were agreed. Sextus was to retain Corsica as well as Sicily and Sardinia, and take the Peloponnese as well; he was to hold this dominion for five years. Consulships were agreed for every year till 32: Libo was promised 34 and Sextus 33, just after the expiry of his quinquennium. For the present, he could have an augurship. In return for all this, he was to raise his blockade of Italy and remove his troops, to undertake to build no more ships and to receive no more runaway slaves, to guarantee Rome's corn supply, and to 'keep the sea free of pirates'. His supporters were to be allowed to return to Italy, with an amnesty for the proscribed: they were to receive some compensation for their vanished property. His slave supporters were to be freed, and his free soldiers were to receive the same rewards on retirement as those of the triumvirs. These last concessions were ones that Antony and Octavian were doubtless very ready to grant: they would placate many of Sextus' supporters, and, if it came again to war, he would not find it easy to recall them to arms.[37]There was also some more constitutionalist talk, this time more grandly of 'restoring the Republic': in eight years' time, perhaps.[38]

The agreement was celebrated by a banquet on Sextus' galley — once again rich material for later legend, with tales of the swashbuckling Menodorus eyeing the cable and thinking of cutting it, to make Sextus master of the world.[39] The agreement was indeed a precarious one, though for less romantic reasons - largely because it diminished and threatened Octavian distinctly more than Antony. It also freed Antony to return to the East. He left Rome shortly after 2 October 39, accompanied by Octavia.[40] He was not to see the city again.

vi. the east, 39—37 b.C.

During the summer of 39 news from the East had been reaching Rome. It was astoundingly good. A year earlier Antony had despatched Ventidius to try to recover Asia Minor:[41] and it seems that Ventidius took Labienus by surprise, forced him to flee eastwards, and finally trapped and defeated him near the Taurus range, perhaps at the Cilician Gates (midsummer 39). Labienus himself fled to Cilicia, but was overtaken there and presumably killed. Later in the summer Ventidius won another great victory at Mt Amanus over Phranipates, the satrap of the newly conquered Syria. Phranipates was killed, and the rest of the Parthian forces fell back beyond the Euphrates. Ventidius had done magnificently, and by the autumn of 39 it was already time for the Senate to reward certain states for their resistance to Labienus — Stratoniceia, Aphrodisias-Plarasa, and (now or a little later) Miletus.[42] The war seemed over. Indeed, there was uncomfortably little left for Antony to do himself.

Still, after spending the winter in Athens he prepared to depart eastwards in the spring of 38. There were a few preliminaries to take care of. The Parthian evacuation made this a sensible time to reorganize some parts of the East, at least provisionally; this time he concentrated on a great swathe from north to south of central Asia Minor. Twenty-five years earlier Pompey had ascribed a considerable tract of western Pontus to Bithynia, but allowed control to remain largely with the cities he had fostered: Antony now reversed the process, weakening the cities and establishing a new strong kingdom of Pontus.88 It was to be ruled by Darius, a descendant of Mithridates Eupator. Deiotarus of Galatia had died, and his possessions in Pontus were assigned to Darius; however, Deiotarus' grandson Castor was recognized as king of Galatia, and he was also allowed the interior of Paphlagonia.89 So far Antony was following the traditional Roman policy of supporting kings from the old regal families; thus also Lysanias was confirmed as king of Ituraea.90 And so far he was not especially concerned with rewarding past loyalties: Lysanias for one had taken the Parthian side.[43] But he also had new, able favourites of his own. Amyntas, once Deiotarus' secretary, was given Pisidia; Polemo of Laodicea-ad-Lycum, whose father Zeno was one of the few who resisted Labienus, received a dominion combining the western part of Cilicia with some parts of Lycaonia.[44] Like Ituraea and parts of Pontus, these were rough, unpacified regions: the new kings evidently had work to do. It was also probably now that Cleopatra was given Cyprus and a region of eastern Cilicia: she too perhaps had a task, for Cilicia and Cyprus were peculiarly rich in timber, and she was presumably to build ships to replenish Antony's fleet.[45] Herod of Judaea also received some further backing. Ventidius and his lieutenant Poppaedius Silo had apparently not tried very hard to displace the rival claimant Antigonus for the throne:[46] he had more pressing concerns. Stronger support could now be given. It seems that Antony began, rather oddly, by recognizing Herod as 'king of the Idumaeans and Samarians': possibly he acknowledged that Jerusalem was for the moment beyond recovery, and granted him this new title in provisional compensation.[47]

It was also now that Antony entered on a new religious policy, and began to insist more emphatically on his identification with Dionysus:[48]a god of liberation and eastern conquest, of course, as well as of vitality and exhilarating release. In Athens, he was duly celebrated as deos Neos

Magie 1950 (e 8jj) 1282П. 15. If Reynolds 1982(8270) doc. 7 refers to the Labienus war (cf. lines 3-4 with her commentary), rewards were also voted to Rhodes, Lycia, Laodicea and Tarsus. On the campaign in general cf. Sherwin-White 1984 (a 89) 303-4.

App. BCiv. v.75.319; cf. esp. Buchheim i960 (c 49) 49-51; Hoben 1969 (E 840) 34-9.

Cf. esp. Hoben 1969 (e 840) 116—19. 50 Cf. Dio xlix.32.3j Buchheim i960 (c 49) 18-19.

" Joseph. A] xiv.3^o, BJ 1.248.

72 App. BCiv. v.73.319 with Gabba 1970 (в 55)0*/on 'he date, Buchheim i960 (c 49) j 1-2. The realm extended as far as Iconium (Strab. xii. 5.3-6.2 (j68Q);cf. Mitford 1980 (e 860) 1242. For Zeno's resistance to Labienus cf. Strab. xiv.2.24— 5 (660Q.

,J Cf. Joseph. A] xiv.392-7, 406, BJ 1.288-92, 297; Buchheim i960 (c 49) 67.

Strab. xiv. j. 2-3 (669C), 671,68 j: cf. R. Meiggs, Trees and Timber in the Ancient Mediterranean World (Oxford, 1982) 117. On the date cf. the inscription published by Pouilloux 1972 (c 189), attesting an Egyptian orpanfyos of'Cyprus and Cilicia' in 38-7; Mitford 1980 (e 860) 1293-4.

App. BCiv. v.75.319 w'th Gabba 1970 (в 5 5) adloc.; Buchheim i960 (c 49) 66-7.

Dio xlvin.39.2.