am much indebted to Dr S. Alcock (Reading) for many helpful comments and suggestions, and especially for directing my attention to a number of useful books and articles.

PI. Criti. 11 ib.

641

Map i j. Grccce and the Aegean.

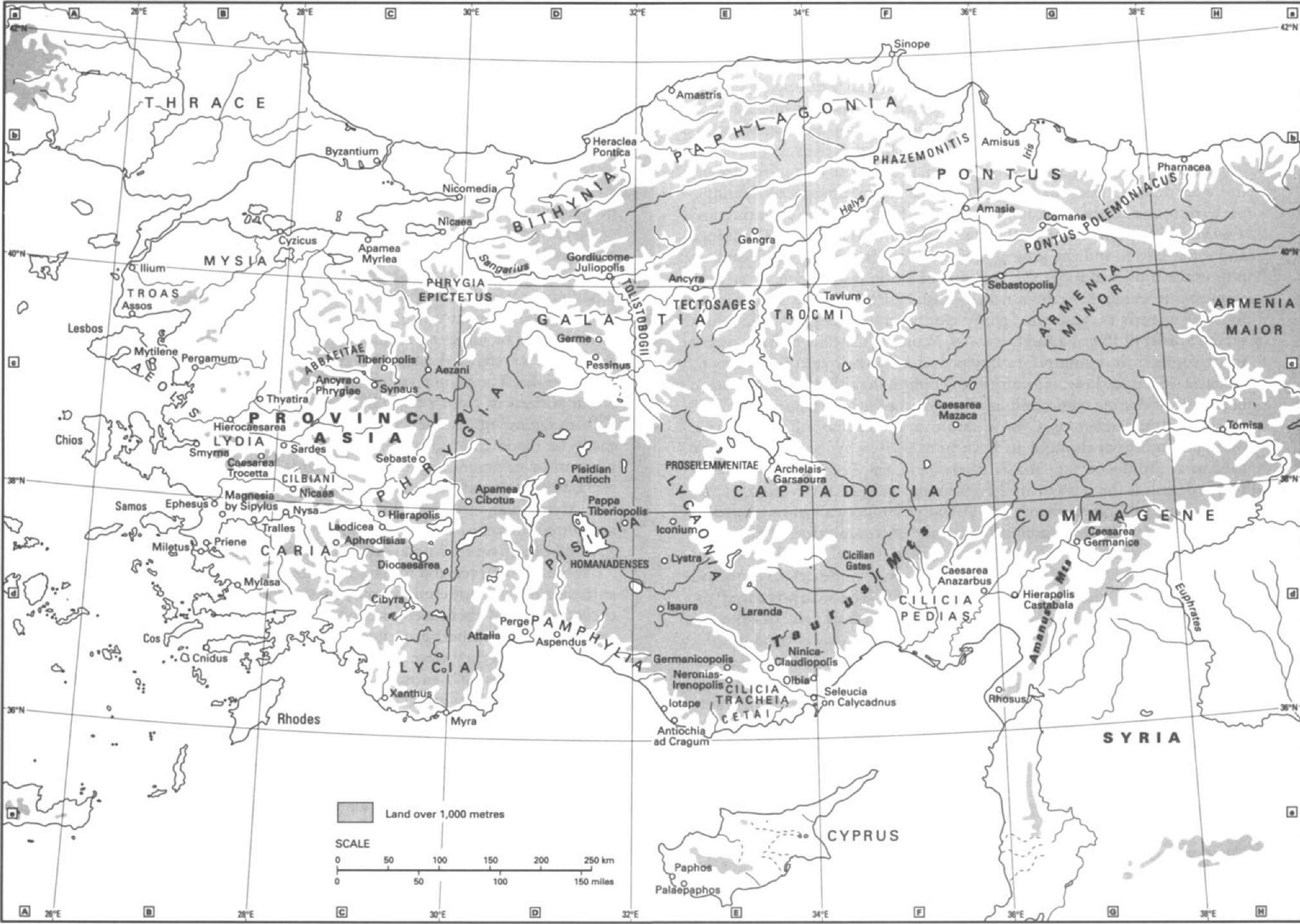

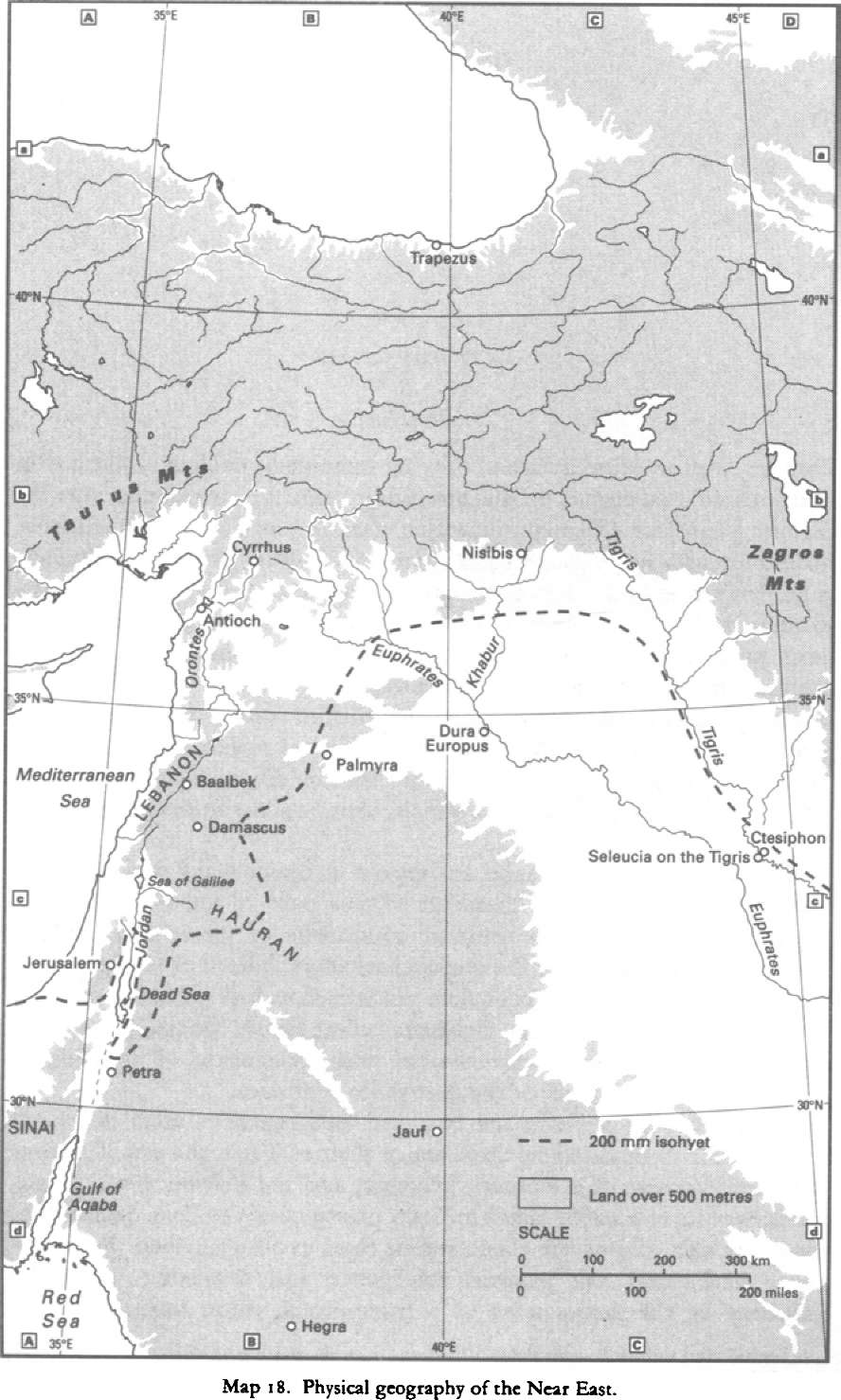

southern extension into Lycia and Cilicia Tracheia, a more continental type of climate takes over, with long severe winters and summers no less dry than those of Greece and the islands. Grain and the vine could be grown, but not the olive; cattle and above all sheep were the staple product, with minerals a potential source of wealth; textiles of all kinds were among the most important products of the entire peninsula. The Greek language had been carried from the mainland and the islands to the west, north and south coasts of Asia Minor by waves of colonists in the tenth and then the seventh and sixth centuries B.C., and hellenization had continued in the wake of Alexander's conquests. In the Anatolian plateau its advance was slow; Lydian, Mysian, Celtic, above all Phrygian and Lycian survived in the villages and tribes of the hinterland, the last two appearing even on inscribed monuments; but the Attalid kings promoted and consolidated Greek art and culture in the west, in what was to become in 153 в.с. the Roman province of Asia, making their capital, Pergamum, an outstanding example of the hellenistic city. Even in central Asia Minor cities with names such as Apamea and Antioch attest the activity of Alexander's successors as creators of poleis. Developed in mainland Greece as a natural product of divisive geography, they proved a means of self-government, a source of military security, a centre of exchange, a focus of religion, a fosterer of education and culture. The wealth, power and self-confidence of the city-dwellers made them people to emulate in Asia Minor. At the same time the strength of the way of life and the institutions that were giving way to urbanization there should not be underrated. A tribal or village organization, reinforced by a common cult, suited sparse populations isolated in hilly country or scattered over a homogeneous and inhospitable plateau and assembling only occasionally to exchange produce at religious centres like Hierapolis in Phrygia and Comana in Pontus or at other markets on the main routes through the peninsula. The differences between the three regions, mainland Greece and the islands, western Asia Minor, and the Anatolian plateau, remained clear and are only lightly masked by the Greek terminology and nomenclature that literacy and public life were imposing.

The manner and timing of the Roman acquisition of these regions was another important variable: mainland Greece fell first, in 146 B.C., after half a century of Roman protestations that it was to ensure Greek freedom that Roman troops had crossed the Adriatic, and after a bitter struggle that ended with many cities deprived of their freedom. In Asia Minor the first acquisition was the bequest of 133, the Attalid kingdom; Bithynia and Pontus were annexed, the first another bequest, the second after the wars with Mithridates the Great, seven decades later. Central Anatolia, as its geography made natural, was treated in the first century as a military problem under the name of Provincia Cilicia: a base for action against pirate strongholds in the mountains and a means of safeguarding the route from western Asia Minor to Syria. The islands of Crete and Cyprus were allowed to survive for longer outside direct control, Cyprus until P. Clodius Pulcher passed a bill for its annexation in 5 8 B.C., Crete in part at least until the end of the Republic.

The Romans were heirs of Alexander and his successors, and benefited from the urbanization achieved under them. In Greece proper there was little more to be done in that direction: it was more a question of preserving the poleis without which control of the empire, for a ruling power whose resources were stretched to the utmost, would be close to impossible in the absence of any alternative organization. Greece was in economic decline in relation to Asia Minor, with its superior fertility and resources. The lot ofRoman governors of Asia was easy, and tempting to the unscrupulous. Even in spite of their greed, urbanization and prosperity would have prevailed, if this area and Bithynia-Pontus had been left in peace. Instead, Greece and western Asia Minor were involved in foreign wars, directly between 88 and 84, indirectly from 74 to 63, and disastrously caught up in civil struggles from 49 to 31 B.C.

II. THE TRIUMVIRAL PERIOD3

The Greek East suffered more in the thirteen years of intermittent civil war that followed Caesar's death than in the swift campaigns that made him supreme. In Asia Minor devastation of the countryside, destruction of cities and their inhabitants, the imposition of fines and exceptional levies came successively at the hands of three parties. First the republicans: late in 43 Brutus forced Lycia to contribute to his war chest, stormed Xanthus, and, together with Cassius, robbed Rhodes (in spite of a plea from Cassius' old teacher Archelaus), Tarsus, and other cities. Client kings also suffered. Ariobarzanes II Eusebes Philoromaios of Cappadocia was executed, Deiotarus of Galatia brought to join the Liberators and send cavalry to Philippi under his secretary Amyntas. Even after the triumvirs' victories at Philippi and Naulochus, Sex. Pompeius' raiding of 35 damaged the area round the Propontis. A second factor was the Parthian invasion under Q. Labienus, 40—38: they advanced along the highway from Syria to Asia and, in spite of resistance from the brigand chief Cleon of Gordiucome, plundered the cities of Caria, notably Mylasa and Aphrodisias, where sanctuaries and private property alike were looted. Finally, Antony: on his arrival in Asia Minor in 40 his first demand was the same ten years' worth of taxes that had been produced for Brutus and Cassius. After Philippi there was the

3 For these events, see App. BCiv. i.57ff; Dio xlviii.26-54; xlvii.24-41; xlix.19-35.

disbandment of thirty legions to be paid for, and in 39—38 and 36—34 campaigns against the Parthians to be financed. The period ended with Antony's mobilization of the East against Octavian, when even the sacred grove of Asclepius on Cos was cut down to supply dmber for ships. The damage armies could do was limited and business carried on; but the effects of uncertainty on the availability of credit, cash loans and all long-term enterprise must be taken into account.

By the Treaty of Brundisium (40 в.с.) Greece from Scodra southwards was under the control of Antony (although in 39 the Peloponnese was abortively assigned to Sex. Pompeius), and so was the whole of Anatolia. Antony exercised patronage in the area, but so did Octavian, granting citizenship to individuals such as Seleucus of Rhosus,4 who continued as his proteges, and extending the privileges of cities. Through a well-placed intermediary who became the city's favourite son, Octavian's freedman C. Iulius Zoilus, 'Caesarian' Aphrodisias secured a decree of the Senate and a law of the People guaranteeing freedom, immunity from taxation, and enhanced asylum rights; an attempt was also to be made to recover looted property.5

The area under discussion falls into three regions. Rulers confronted with the problem of controlling each would be guided by political, military and economic factors. Mainland Greece, Crete and the Cyclades in political terms were well able to govern themselves; economically the mainland at least was an area in decline and depopulation, unlikely to make much contribution to the cost of running it and very unlikely to present any threat to security. Next, western Asia Minor and the adjacent islands: the provinces of Asia and Bithynia were long habituated to obedience as the subjects of Lydian, Persian and hellenistic monarchs; they, like the more remote southern coast, Pamphylia and Cilicia Pedias, had enormous economic possibilities: two-thirds of the cities coining in Asia Minor under Augustus and Tiberius were in the province of Asia. Third, the Anatolian plateau, politically and economically underdeveloped, in spite of Pompey's city foundations in Pontus, was daunting and as yet unprofitable. The three regions were accordingly handled differently both by Antony and by his successors in power, the emperors.

It was for sound political, economic and military reasons, then, that only Asia, Bithynia and Cilicia Pedias were governed as Roman provinces between 42 and 31 в.с. The rest of Asia Minor was subject to skilfully chosen client princes6 (Lycia was an autonomous federation of

4 EJ2 301. 5 Reynolds 1982 (в 270) 7-12.

6 For the vicissitudes of dependent rulers, see Magie 1950 (e 855) 427-515; Bowersock 1965 (c 39) 42—61; Jones 1971 (d 96) 110-214; Sullivan 1978 (e 878) 732—98; 1980 (e 879) 913—30; 1980 (e 880); stemmata at Sullivan 1980 (e 879) 928 and 1980 (e 880) 1136; Braund 1984 (c 254) for individuals. For Strabo's insight into the value of client kingdoms, that their rulers, unlike Roman governors, were always on the spot and armed, see xiv.5-5-9 (671c).

twenty-three cities7). They, not Rome, had the burden of defending and administering it and the duty of supporting their patrons, who could give, take, or trim their kingdoms as he chose. On Deiotarus' death in 40 his son Castor received Galatia and the interior of Paphlagonia; Deiotarus' share of Pontus, the coastal area, went to Darius, son of Caesar's enemy Pharnaces and grandson of Mithridates the Great; Amyntas received northern Pisidia, and Polemon I, son of Zeno of Laodicea, who had resisted Labienus, took Lycaonia, Iconium and the adjacent parts of Cilicia Tracheia; Pedias, like Cyprus, passed into Cleopatra's hands, Olba, west of Pedias, was ruled by the priesdy house of the Teucrids and the kingdom of the Amanus in the east was left under its hereditary ruler Tarcondimotus.

Antony rewarded success. On Castor's death in 37, Galada, Lycaonia and the Pamphylian coast were added to Amyntas' domain; Castor's son Deiotarus Philadelphus received Paphlagonia. Polemon, having to surrender Lycaonia to Amyntas and his possessions in Tracheia to Cleopatra, was given in return Pontus beyond the Iris river, with Phazemonids, Armenia Minor and Colchis; while Archelaus, son of the hereditary priest-ruler of Comana, acquired Cappadocia on the departure or death of its king, Ariobarzanes' brother Ariarathes X. Cleopatra was also given part of Crete, although Antony claimed to have found a Caesarian decree freeing it.8 The remaining cides were left to govern themselves and their territories.

III. THE AUGUSTAN RESTORATION9

Octavian's esdmate of the eastern regions that came under his sway after Acdum and the decisions he took about their future government were based in part on autopsy, as he passed through Asia Minor in 30 в.с. and wintered on Samos, while his further journey to Italy was broken at Corinth. Under the considered arrangements established in 27 only minor adjustments were made to the overall system devised by Antony, with two areas now brought under direct Roman control: Crete (only Lappa and Cydonia keeping their freedom) and Cyprus, which had no privileged cides.

There were further distinctions to be made: were any of the provincial areas to have Augustus as their governor, with his legate acting on the spot, or were they to be left to other senators selected on seniority and by the lot? Which of these latter, the 'public' provinces, were to have ex- consuls as their governors? The answers were determined by past tradition, present and especially military needs, and the princeps' own

7 Strab. xiv.).}~9 (665cf). 8 Dio xi.ix.;2.4f; Cic. Phil, n.97, with Sanders 1982 (e 871) 5.

9 See especially Strab. viii—xvn (552—840c), and Dio u-lvi.

security. All the areas were entrusted to governors selected by seniority and the lot except Cyprus. That was a place where a governor might see action, unruly perhaps after its second takeover by Rome; but the trouble it could cause was minor and in 23 or 22 it was returned to the lot, an unpromising assignment for its proconsuls; the copper-mines were to be handed over on lease to a client monarch, Herod of Judaea.10 Even Macedonia was normally to be a public province, although legati Augusti are also found there.11 Greece was detached from Macedonia in 27 and became the separate senatorial province of Achaea, including Aetolia, Acarnania, part of Epirus, and the Cyclades, probably with Corinth as the main seat of government. In spite of cultural and economic ties with Athens, the islands and Asia Minor, Crete was united with Cyrene as another province for proconsuls of praetorian status. Not Cnossus, which had had land worth 12,000 sesterces a year assigned to Capua in compensation for territory lost to veterans in 36 and which now itself became a colony,12 but pro-Roman Gortyn, in the south of the island and more convenient for commuting governors, was the administrative centre. In our second region, western Asia Minor, Bithynia likewise and the parts of Pontus that still belonged to the province were, assigned to another proconsul of praetorian status, but wealthy Asia was declared consular and in 27 became one of the two plum posts that the Senate could offer ex-consuls, the other being Africa, which had a legion but fewer amenities. The Lycian federation, whose prudent administration was admired by Strabo,13 had earned and retained nominal autonomy. The federation employed a sophisticated system of proportional representation on its administrative bodies, the electoral assembly and council.

How much was meant by the freedom accorded to leagues like the Lycian and that of the free Laconians (Eleutherolacones), to whole islands like Corcyra, to individual cides like Delphi, Athens and Nicopolis (some, like Mytilene,14 were in possession of treaties too), is a quesdon. Theoretically enclaves exempt from the governor's jurisdiction, they still had to reckon with the emperor. Augustus intervened in Athens and Sparta, where down to about 2 b.c. he had relied on a partisan, C. Iulius Eurycles, son of a privateer, to guide the state in his own and Rome's interests; he actually deprived Thessaly and Cyzicus of freedom altogether. Cyzicus lost its freedom for five years for executing Romans, though a proconsul of Asia declared Romans subject to local

Dio Liv.4.1; Joseph. AĴ xiv. 128.

Tarius Rufus, cos. 16 b.c.: EJ2 268; L. Piso, cos. 15 b.c.: EJ2 199 with R. Syme, Aktenits VI. Intern. Kong, fur gr. undlat. Epigr. Miincben tf?2, Vestigia xvii (Munich, 1973) 595f. Cf. ch. 10, n. 9, ch. 134, p. 567.

Dio хых.14.5; for date and interpretation, sec Rigsby 1976 (e 867) 322-30.

Strab. xiv.3.2 (664c). 14 EJ2 307.

law on Chios. Other free cities learnt the lesson: in 6 в.с. Cnidus recognized the princeps' jurisdiction in a local homicide case.15 The governors of unarmed provinces spent much time on jurisdiction, going on circuit round the assize centres (although no circuit is attested in Crete); in Asia the task was alleviated by having the conventus centres on the coast or on the highway that led from Ephesus over the plateau to Cilicia.

Considering the third region, Octavian no more than Antony took it to be ready for direct Roman rule. Already during the tour of 30—29 he had made it clear that the dispositions of 36 would not necessarily be changed, although there had to be adjustments and it took a decade to achieve stability. Loyalty to Rome and himself brought rewards, but loyalty to Antony was not an unforgivable offence; indeed, it promised well, if it could be transferred to the new master. Amyntas of Galatia, like Deiotarus Philadelphus of Paphlagonia and Cleon of Gordiucome, who was promoted to the priesthood of Comana Pondca, secured confirmation by changing sides before Actium, and received part of Cilicia Tracheia. But Archelaus of Cappadocia was not displaced and, despite internal efforts to unseat him, retained his underdeveloped but lucrative and strategically important kingdom until a.d. 17, taking over in Tracheia after Amyntas' death. Polemon I of Pontus lost Armenia Minor to Artavasdes, a displaced claimant to the Parthian throne, but was to remain the chief support of Rome in the north of Asia Minor. He kept the southern shore of the Black Sea (an area that had been strengthened with settlements official and unofficial at Heraclea Pondca — a Caesarian venture that had not survived - and Sinope, which became Colonia lulia Felix in 47), Colchis, and the mines behind Pharnacea. Polemon was less successful in his charge of keeping the Bosporan kingdom on the northern side of the sea under Roman control, and perished there in 8 B.C. He was succeeded in his Anatolian possessions by his widow, Pythodoris of Tralles (she died in a.d. 7-8). In one of the marriages that created for Augustus a nexus of dynastic families and a supply of potential client rulers who were born to the job, Roman citizens, and educated at Rome, Pythodoris' daughter Antonia Tryphaena was given to King Cotys of Thrace — whose sons were also to become rulers in Asia Minor; she herself went on to marry Archelaus of Cappadocia.

Only in minor principalities did Octavian assert a conqueror's rights. At Heraclea Pontica, where Antony's nominee Adiatorix had massacred Caesar's colonists, there had to be a change, but the tyrant's elder son Dyteutes was given a compensating position, the priesthood left vacant through the untimely death of Cleon. Nicias the tyrant of Cos had to pay for his patron's depredations; at 'free' Tarsus the Antonian dynast and

14 Dio Liv.7.6, 23.7 (Cyzicus); EJ2 317 (Chios); 312 (Cnidus).

poet Beithys was replaced by Augustus' old tutor Athenodorus; and the kingdom of Hierapolis Castabala was kept from its natural heir, the son of the late Tarcondimotus Philantonius, undl 20 B.C. The same year saw Augustus achieving a stable settlement of Commagene, probably at his third attempt. The regime of the new ruler and his son Antiochus III survived until a.d. 17, like that of Archelaus and Tarcondimotus Philopator. Archelaus' kingdom was enlarged in 20 в.с. by the addition of Armenia Minor on the death of its ruler, and the Teucrids of Olba, the Cilician city devoted to Zeus, now resumed the priestly and secular power that their forbear, Aba the protege of Antony, had lost.

The core of the system was the Galatian kingdom, for its size, and because the main route from Asia to Syria passed through it. Not far to the south of that route was the untamed mountain area of Pisidia, which disjoined the plateau from Pamphylia. Amyntas lost his life carrying out the duties of his position. The Homanadenses of Pisidia captured and killed him, and by the end of 25 в.с. Augustus had created a third province in the peninsula, Galatia, of which only a part was inhabited by the Gallic tribes of the Tectosages and Tolistobogii (west of the Halys) and Trocmi (east of the river). The unwieldy kingdom was incorporated wholesale, with the exception of central Tracheia. Galatia like all newly acquired provinces was under the charge of Augustus, who sent a legate to deal with his new responsibility. M. Lollius had not yet held the consulship, but some later governors under Augustus were to be of consular rank and until a.d. 6 the province probably had a garrison of one legion (VII Macedonica) or even two.[779]

The particularly dangerous area of Pisidia was put under guard in 25 B.C. by the foundation of six veteran colonies, the chief being Pisidian Antioch. In 6 B.C. a road was constructed, the Via Sebaste, to link them, and probably within the next two or three years (rather than beforehand) the forty-four castella of the Homanadenses were captured by the distinguished governor of Galatia P. Sulpicius Quirinius, and the tribe broken up. It was not a complete pacification of southern Asia Minor: a rising was put down in a.d. 6 but Quirinius had done the main work and it was not necessary to put the province under another consular governor, as far as is known, until Cn. Domitius Corbulo took command under Nero.[780]

When in 6 в.с. Deiotarus Philadelphus or his heir died, not only eastern Paphlagonia but Phazemonitis was joined to it. With the accession three years later of the region south of Phazemonitis and east of Galatia (including the city of Sebastopolis) another district hitherto under a dynast came into the province, making it the same size as Asia and twice that of Bithynia. The following year Amasia too passed from dynastic control into the province of Pontus, but eastern Pontus remained under the widow of Polemon I.

These were acute administrative decisions, taken some in the first months after the victory at Actium, others in response to sudden crises, others again after mature reflection. As the responsibility of one man and his advisers they may be considered as part of a policy, that of the gradual advance of direct Roman rule, when that was safe and profitable. But these decisions did not themselves solve the political, social and economic problems that Octavian inherited from the period of the revolution. Overall it is true to say that Roman rule was not popular in the Greek-speaking provinces and many communities (Athens is a single but the most distinguished example) had three times committed themselves to the losing side in civil war. Economic problems stemmed in part from these wars and, in Greece especially, from the Actium campaign — Plutarch's great-grandfather used to tell how the entire male citizen population of Chaeronea was carrying grain down to the sea under the whips of Antony's agents when the news of the battle arrived and 'saved the city'[781] — but also from longer term causes. If they could be relieved, political problems might also diminish, but there was an irreducible dissonance between the realistic, power-orientated Roman view of the empire and the idea of Greek poleis as to their position in the world. In a work that can be dated nearly as late as a century after Augustus' death Plutarch had to warn his Greek readers to forget what their ancestors had achieved as sovereign peoples in the Persian Wars of the fifth century в.с.[782] The regime of Augustus did not succeed in putting an end to anti-Roman feeling and prophecies that foretold the end of Roman rule, but here again, although loyalty was rewarded (Hybreas, the rhetor of Mylasa who had resisted Labienus, won Roman citizenship and a high priesthood of Augustus, and the descendants of Zeno of Laodicea have been seen benefiting from his staunchness), Augustus did his best for reconciliation, and his first acts included distributing grain to the cities and remitting their debts.[783]

Greece and Asia Minor were to continue to receive personal attention from the princeps and his family. In 23 в.с. Agrippa was in the East, able to take authoritative decisions, while Augustus himself returned in 21, carrying out an inspection of Asia Minor and spending the winters of 21—20 on Aegina and 20-19 on Samos. The East fell once again to Agrippa's care between 18 and 13 and this time he saw more of it than the island of Lesbos. But for a last-minute refusal it would have been in Tiberius' charge from 6 to i в.с. (he already knew Asia Minor from his mission to Armenia in 20 b.c.). As it was, Gaius Caesar was there from 1 b.c. until his death in a.d. 4. Thirteen years later came another Caesar with imperium maius, Germanicus.

Whether close at hand or in Rome or the western provinces, Augustus and his successors were accessible to embassies (for the cities in their own estimation were conducting diplomacy) bearing letters and oral requests, as they were also to private individuals. Strabo tells how in 29 B.C. the tiny fishing community of Gyarus went to make representations to their new ruler about its tax burdens.21 Before he had been established as princeps for more than a period of months Augustus had been approached in Spain by parties from all three regions with which we are concerned: the Thessalian League and Archelaus were engaged in litigation, as was Tralles, a city of Asia which had also suffered earthquake damage, along with Thyatira, Chios, and Laodicea. A personal friend, the eques Vedius Pollio, was sent to supervise the restoration of the cities of Asia.22

Besides pleas for help and tax remission, questions of status and privilege were frequently the subject of embassies, as they had been (and were to remain) of concern to Aphrodisias: freedom, immunity, grant of a treaty, asylum rights; even, when communities of humbler status were involved, the right to become a polis at all and to possess the institutions of a city, above all a city council. Petitions of this last kind must have been heard with sympathy, the emperors inherited from the hellenistic monarchs a wish to be immortalized as founders and restorers of cities. In the time of Augustus himself many towns came to be called Caesarea, like Tralles, or -caesarea, like Hierocaesarea, in Lydia, once Hiera Kome (the sacred village), Sebastopolis, Sebaste, or -sebaste. Not all belong to areas under direct rule: they were creations of, or were renamed by, client rulers, like Caesarea Mazaca, capital of Cappadocia, Kayseri to this day, or Caesarea Anazarbus, refounded in 9 в.с. probably by Tarcondimotus Philopator.

Greece in particular needed help. It had not suffered as parts of Asia Minor had done, but its natural resources were more meagre and the wealth that comes from empire had eluded Athens and Sparta three centuries previously. The prospect before it was one of economic compeddon with regions such as Italy and Spain which were better able to produce the same crops and manufactures. Strabo on Arcadia, Messenia and Laconia repeats a story of depopuladon already told in general terms by earlier writers; he says that except for Tanagra and

Strab. x.j.i (485c).

Suet. Tib. 6; Strab. xn. (579c); Agathias, 11.17; Sutherland and Kraay 1975 (в 359) 1363.

Thespiae the cities of Boeotia (which had suffered heavily from Sulla and where the flooding of Lake Copais had played its part: a warning not to expect uniform conditions even over a single province) had become litde more than villages or (in the case of Oropus and two other cities) fallen into ruin. Arcadia, Aetolia and Acarnania are given over to ranching like Thessaly, and the copper-mines of Euboea had given out like the silver of Laurion. Looking back a century and a half later Pausanias wrote that the fortunes of Greece reached their nadir between the fall of Corinth and the reign of Nero.23

It is not surprising, then, that Roman intervention bordered on the invasive. A special effort had been made at Caesar's instance to restore Corinth by colonizing what remained of the city destroyed in 146 b.c. with civilian settlers from Rome under the name Laus lulia Corinthien- sium. The colonists, including freedmen as they did, were not well thought of, but by 7-3 B.C. Corinth was once more in charge of the biennial Isthmian games, as well as celebrating quadrennial Caesareia; and the colonists were to become thoroughly assimilated.24 Another colony was founded on the Gulf at Dyme at about the same time, reinforcing Pompey's settlement of ex-pirates there. But nearly three decades later a new colony at Patrae acquired territory across the water and incorporated villages close to it, so that Dyme was completely eclipsed. Patrae was to be the centre of the manufacture and export of flax.25

But Augustus' personal creation in Greece was an entirely new city, Nicopolis, which he established near the site of the battle of Actium through a synoecism of surrounding peoples: Ambracia, Amphilochian Argos and Alyzia became dependencies. It was an artificial entity in an undeveloped area, and must have uprooted some of the country populadon, but the festival it celebrated brought visitors to its two harbours, business and revenue; it began to grow rapidly, a precocious harbinger of the Greco—Roman culture of the second century.26

New and redeveloped cities could not usurp Athens' artisdc and intellectual primacy. That depended on her past, as current archaism in art, architecture and epigraphy showed. A mecca for students, tourists and devotees of religion, she also exported works of art and derived a

25 Strab. viii.7.5-8.5 (388c); ix.2.16-18 (406c); x.i.8-10 (447c); cf. Polyb. xxxv1.17.5- Wallace 1979 (e 886) 173-8, confirms; Dr S. Alcock draws attention to Bintliff and Snodgrass 1985 (e 816); see also Baladie 1980 (e 812) 51 jf. But Dr Alcock rightly warns against taking what may be a literary topos, a moralizing tone, or disregard for contemporary Greeks too much on trust: she draws attention (e.g.) to N.K. Petrochilos, Roman Attitudes to the Creeks (Athens, 1974) 63-7; Pausanias: vii.17.i, with Baladie 1980 (e 812) 323.

Strab. viii.6.20 (578c); (381c); hellenization: [Dio Chrys.] xxxvii. 26.

Strab. viii.7.5 (387c).

24 Strab. vii.7.6-7 (325c); N. Purcell, 'The Nicopolitan synoecism and Roman urban policy', Proceedings of the First international Symposium on Nicopolis (1984).

notorious income, the more valuable now that her silver-mines were exhausted, from selling her citizenship: 'Ten sacks of charcoal imported and you too will be a citizen; if you bring a pig as well you're Triptolemus himself', wrote Automedon.27

Connexions with Athens, as well as with other Greek cities, were sought after by rulers within the Roman sphere of influence and by literary men. Antony had shown respect for Athens in spite of her support for Pompey and the Liberators. He and Octavia had been hailed as Theoi Euergetae and the aristocrats he had put in power in 38 B.C. were grateful for that and for his return of Aegina and other islands, with the revenue they brought.

Augustus' treatment of Athens was paternalistic. He showed his displeasure with her by residing at Aegina for part of a winter (22-21) and by freeing that island, and Eretria, from paying tribute to Athens. He also forbade the citizenship sales. The Athenians made up for the loss of revenue by granting foreigners the right to have statues erected in the city, but the statues were not always freshly carved for the individual honorand. For exceptional benefactions there were choicer honours: C. Iulius Nicanor of Hierapolis in Syria, a poet who restored the island of Salamis to Athens at his own expense, earned the titles of New Homer and New Themistocles. Embarrassing or invidious, they were later expunged.28

In spite of periods of estrangement, Athens benefited from Augustus' generosity. Tesserae found in the city29 reveal that she had been included in the grain distributions of 31 and Augustus' reign saw the reinstitution of Athens' embassy to Delphi, on a more modest scale than before, as the Dodecas. There was also considerable building activity, the restoration of sanctuaries in Attica, perhaps also in the Piraeus. In the city itself Augustus personally, on appeal from an embassy led by Eucles of Marathon, had by 20 B.C. accepted responsibility for the completion of the Roman market; in the old Agora Agrippa built his Odeion, moving the temple of Ares from outside the city into juxtaposition with the new building, and a new set of baths was constructed outside the old Agora. The overall conception and detail of the complex alike showed the influence of Roman ideas, in particular echoing the Forum Augusti and the temple of Mars Ultor; the buildings left litde room for the vigorous public activity of the past.30

Augustus was not insensitive to Athenian susceptibilities. He was

Dio liv.7.if, with G.W. Bowersock, CQ NS 14 (1964) i24f; Antb. Pal. xi.319.

Dio Chrys. xxxi.i.6; 1G n2 3786-9, etc., with Jones 1978 (e 1020) 226-8, reaffirming an Augustan date. 29 See Rostovtzeff 1903 (e 870).

30 Shear 1981 (e 873) 361; Thompson 1987 (f 593) 4-9, for imperial political interpretation of the reconstruction of Ares, see Bowersock 1984 (c 40) 173.

initiated at Eleusis in 31 and about four years later the city is found beginning to issue a coinage that does not bear his head on the obverses. This 'autonomous' coinage continued until the reign of Gallienus; the privilege was enjoyed also by Corcyra, Delphi, Sparta and Corinth. In return Athens did not stint honours to Augustus and his family. A round Ionic temple on the Acropolis which may have been influenced by the temple of Vesta at Rome, though its order is modelled on the Classical Erechtheum, belongs to the decade immediately following his accession to sole power; Augustus is Theos on a dedication made at Delphi, a decree of the Council of Six Hundred resolved in 27—26 to celebrate his birthday (a day already associated with the restoration of freedom), and the ephebes held a festival called the Augustan Contest. The moving of the temple of Ares may be connected with the imperial cult, for in a.d. 2 Gaius Caesar, then in the East, was honoured under that патё.[784]

Eucles was a member of the oligarchy that emerged in Augustan Athens. He succeeded his father as supervisor of the construction of the Roman market, held the positions of archon and strategos and five times acted as priest of Apollo in the Dodecas. The stability of the oligarchy is suggested by the fact that the same three men held the leading positions in that embassy on all five occasions of its dispatch under Augustus.

Discontent remained in Greece. In a.d. 6, according to Cassius Dio, it was prevalent in cities throughout the Roman world. At a date unknown, (Cassius) Petreius, son of a loyal Caesarian, was burned alive in Thessaly, and the district lost its freedom.[785] In the Peloponnese even Eurycles had to be exiled in about 2 B.C.: he certainly involved himself in eastern Mediterranean politics, visiting both Archelaus of Cappadocia and Herod of Judaea, perhaps also in imperial court intrigue, and it was claimed that he had disturbed the cities of Achaea.[786] At Athens the swivelling round of Athena's statue to face west and her spitting blood, which heralded a visit from Augustus (probably that of 21), were no good signs, and unrest is attested in a.d. 13, presumably on the part of the less well-off members of society; it was fatal to its leaders. Athens did not enjoy good repute under the Empire. When the whole province joined Macedonia two years later in complaining, not only about taxes, but about the cost of maintaining the proconsuls in their state, it must have been the upper classes who took the lead. The two episodes, which ended in the transfer of Achaea and Macedonia to the jurisdiction of the governor of Moesia, were connected, though it was probably not the unrest that induced Senate and emperor to make the transfer.[787] Economic problems affecting all classes were probably only midgated with the establishment of peace in 30 B.C. They may be illustrated from an inscription of a.d. 1—2, which shows Lycosura in Arcadia unable to attract competitors for its games in an Olympic year, and in debt to the provincial fiscus because of crop failure.[788]

As Roman armies advanced north and east in the Balkans, necessitating the creation of a new province, Moesia, Greece fell further behind the market constituted by legions and auxiliaries and became ever more a backwater. One of her most important exports, marble, which came from Euboea, Attica, Laconia and Paros, was in any case in the hands of the state; imperial marks begin in a.d. 17. Athens became more prosperous under Augustus, but her ceramics were giving way even at home to Arretine ware and her cheap lamps could hold only the domestic market.

That the provinces were able to appeal in concert shows that the leagues of the classical and hellenisdc periods, created to deal with problems and powers too great for individual cities, still had a role to play in the absence of a provincial koinon such as we shall find in Asia and Bithynia. The Achaean League, though much smaller that its earlier namesake, which had been dissolved after the catastrophe of 146 B.C., and representing only twelve towns in south-east Thessaly and on the north coast of the Peloponnese, including Elis and Sicyon, must have acted with the Panhellenic League of Free Laconians (Eleutherola- cones), containing twenty-four cities whose freedom from Spartan rule had been granted, or more probably confirmed, by Augustus. In Thessaly another league survived, centring on Larissa, its council representing towns in proportion to their size and exercising considerable authority in local affairs; and under Augustus the constitution of the Delphic Amphictiony had Athens, Delphi and the emperor's own Nicopolis sending delegates to each session (respectively one, two and ten), while the remaining members were represented in rotation (Macedonia and Thessaly by two each).36 Nicopolis' dominance did not survive: by Pausanias' own time it was on a par with Macedonia and Thessaly with six votes. Other districts had minor leagues that survived: those of the Phocians, Boeotians, Magnetes and Arcadians. Crete too, land of a hundred cides in Homer's time,37 had a koinon, of twenty cides only as a result of amalgamation and the absorption of one by another.

But it was the province-wide organization of western Asia Minor that scored the first and paradigm diplomatic success of the new age by establishing a firm relationship with the ruler when he was in the area in 29 в.с.38 Octavian on Samos received delegations from both Asia and Bithynia, the first representing an organization of long standing, the peoples and tribes in Asia and those individuals judged friends of the Roman People, or in short the koinon of the Greeks. Already known from the nineties b.c., when they were doing honour to the proconsul Mucius Scaevola, they had a fully-fledged council by 48 at the latest and were addressed by Antony in a letter giving permission to the Association of Victorious Athletes to commemorate its privileges on a bronze tablet.39

Octavian accepted the temples offered by these embassies on condition that Rome too received cult. Roman citizens in the provinces were to devote themselves to Rome and the Deified Iulius at Ephesus and Nicaea; the more modern Pergamum and Nicomedia were chosen for Octavian's temples. Partial acceptance of the honours showed the cities of Asia Minor that Octavian was well disposed, though not theirs outright. Prominent individuals benefited from the cult through the opportunities for self-advertisement that management offered them, and the city populations of Pergamum and Nicomedia and other large cities through the festivals laid on and the crowds that they attracted. Similar provincial koina came into existence as the benefits were perceived or as new provinces such as Galatia were created.

Homage to proconsuls of Asia did not long continue: the last known to have received it was C. Marcius Censorinus who died in office in a.d. 2. They were not even accorded the honorific titles of Saviour and Founder, which likewise became a prerogative of the princeps, the last to bear them again being Censorinus. Similarly, outstanding local dignitaries ceased to be offered cult; the last known was Artemidorus of Cnidus. The divine honours which had been accorded to Theophanes of Mytilene, Pompey's secretary and biographer, contributed to the downfall of his descendants in a.d. 33.40

For his part Octavian's first concern in the years after his victory must have been the restoration of prosperity, and so taxability. Recovery was promoted by the resumption at Ephesus and Pergamum between 28 and 18 of the issuing of coins, the cistophori, tetradrachms last struck by Antony in 39 B.C. The quantities now issued were not to be approached

51 Horn. 11.11.649. 38 Dio li.20.6-8. « Reynolds 1982 (в 270) 5; EJ2 )oo.

40 Am. Greek Inter, in the British Mm. 787, with Price 1984 (f 199) 48 (Artemidorus); Tac. Ann. vi.i8.j-j (Theophanes' posterity).

again until Hadrian's time. Octavian was also attentive to the plaints of cities which he knew to have suffered as a result of the Parthian invasion, and his ready aid after the earthquake of 27 was again available to Cyprus when it was striken in 15 B.C., after which Paphos took the princeps' name and adopted a new calendar, and to Cos.[789] Not everyone gained: on his visit of 21—20 Augustus did indeed make gifts of money to some communities of Asia and Bithynia, but he imposed additional burdens on others.[790]

Imperial attentions were more easily secured if a community possessed such an advocate at court as Tralles did when it sought help after the earthquake of 27;[791] Chaeremon may have been brother-in-law to Polemon I and he was certainly a member of a notable pro-Roman, although also previously pro-Pompeian and pro-Antonian, family. The practice, valuable to both sides, of granting favoured individuals and families privileged access to the ruling authority, was to continue. More generally, it was to ancestral connexions that Ilium owed the rebuilding of its temple to Athena.44 Not surprisingly cities made every effort to bring themselves to the princeps' attention through embassies and patrons known to him, as they had to that of earlier statesmen and dynasts. By 9 b.c. Augustus' benefactions were such that the proconsul Fabius Maximus could tell the koinon that they would never be surpassed, and it agreed to make the princeps' birthday the start of the new year in Asia.45

Homage from individual cities also went along with the benefactions, acknowledging or encouraging them. Some cities combined it with reconstruction: Ephesus had its upper square modified to incorporate imperial temples and a stoa basilike;46 others, notably those of Lydia, adopted the year of the Battle of Actium as their new era. Twenty years after the institution of the provincial cult ten Roman assize centres had their own temples, and together thirty-four cities in the whole of Asia Minor are known to have celebrated Augustus' cult, including even such remote places as Gangra. In eleven of them, including Mylasa, he shared it with that of Rome, his cult an addition to hers. Here too prominent individuals benefited, as on Chios, where the descendants of the founder participated in the ceremonial.47

Although the cult was the creation of organized communities, notably of poleis, and some uniformity may have resulted from guidance offered by governors, it was not confined to provinces or acquired only on provincialization. Lycian Xanthus had a temple of 'Caesar', Myra and

Tlos called Augustus Benefactor and Saviour (or Founder) of the whole universe.48 Indeed, the foundation of a festival in the princeps' honour played its part in maintaining inter-city connexions and diplomacy. Mytilene announced the establishment of games in honour of Augustus, and copies of the decree were to be set up in Pergamum, Actium, Brundisium, Tarraco, Massilia, Antioch and elsewhere.49

In Asia Minor as in Greece Augustus encouraged the development of city life, more by way of innovation here than in restoration; even in the province of Asia it was lacking in remoter, inland districts. The synoecism of Sebaste in Phrygia, attested in a verse inscription, may be paralleled at Caesarea Trocetta in Lydia.50 This is not to be compared with Nicopolis. The princeps merely acceded to the wish of leading inhabitants of a district for organization and status as poleis. A more gradual development was one by which an existing capital of the koinon of a number of villages became a city within a territory: in Mysia the Abbaeitae crystallized into the cities of Julia Ancyra, Synaus and Tiberiopolis. The people who were coining under the name of 'Cilbiani about Nicaea' in Nero's reign became the 'Nicaeans Cilbiani' or 'in the Cilbian region' only under Septimius Severus.51 Changes of name could easily be made and did not necessarily involve changes of substance, physical or in organization: so at Caesarea Anazarbus in Cilicia Pedias, and Caesarea, later Germanice, in Bithynia, inhabited by former serfs of the Mygdonian tribe; Iuliopolis, the former Gordiucome, never amounted to much. What the princeps contributed is uncertain; what he spurred others on to do may have been almost as important.

Augustan intervention in Asia and Bithynia by official settlement and colonization was not conspicuous; the colony of Alexandria Troas was exceptional. But there were independent immigrants. After the Sullan setdement the numbers grew again, and in Cicero's province of Cilicia a generation later they were already numerous enough to be subject to a levy. There was also substantial immigration into mainland Greece, notably in the Peloponnese where they acquired landed property on a large scale and formed a persistent element in their communities. Romans formed a relatively wealthy stratum in the cities in which they settled, but they do not seem to have held aloof from their neighbours: Roman citizens collaborated with natives in the restoration of Messene; L. Vaccius Labeo of Cyme, who endowed the gymnasium under Augustus,52 is only one of many such Roman benefactors. Intermarriage between Romans and local aristocrats was soon to produce candidates

« IGRR hi 482 (Xanthus); 546 (Tlos) 719 (Myra). « IGRR iv 59.

50 IGRR iv 682. 51 See Jones 1971 (d 96) 78.

52 Immigration: Wilson 1966 (a 106) 127-51; effect on Strabo: Baladie 1980 (e 812) 195; Messene: Bull, ip, 1966, 200; Labeo: IGRR iv 1502; land-owning: IG v 1. 1452.

Map 16. Asia Minor.

for the Senate and at a humbler level the elaborate and idiosyncratic funerary monuments of such a town as Aezani were to house the descendants of Italian immigrants alongside the bearers of Greek, Macedonian and Phrygian names.[792] When the death of Roman citizens at Cyzicus led to loss of freedom the victims were not necessarily immigrants: they could equally have been enfranchised natives.

Business and immigrant landowners, part of whose extensive properties were destined eventually to go to the substantial imperial holdings, are to be found further east in the peninsula, but there Augustus pursued a more active policy of urbanization, notably in the Galatian province and especially round the area in which Amyntas met his death and on important routes. Besides the six veteran colonies founded in 25 B.C., numismatic evidence reveals other colonies in the Galatian province founded as early as Augustus' reign: Germe in Galatia proper, Iconium on the border of Phrygia and Lycaonia, Ninica in Cilicia Tracheia, on the route south from Iconium via Lystra and Laranda over the Taurus to Seleucia on Calycadnus; at Ninica and Iconium the colonies seem to have been part of double communities of which the native components were to find advancement as Claudiconium and Claudiopolis.[793] Further, unofficial colonists thought to have been settled by Augustus on ager publicus at Attalia, where Roma Archegetis, the Foundress, was worshipped (unless the settlement there was a spontaneous development on public land sold off to them) and at Isaura would also have helped to strengthen the Roman presence in composite communities.[794] But there was voluntary change as well: Pliny writes of the 195 'peoples and tetrarchies in Galatia,[795] and he is borne out by the relatively small number of cities coining there, less than sixty. The Gauls themselves, once the scourge of Asia Minor, began to move into line. In token of loyalty they referred to themselves as Sebasteni, each tribe at first ignoring the township on which it centred. Then they are found as the Sebasteni Trocmi Taviani (Tolistobogii Pessinuntii) with the town's name incorporated. The development of Sebaste Ancyra of the Tecto- sages came quickest: Ancyra was the capital of the new province and the centre for the provincial cult of Rome and Augustus, with an Augustan or early Tiberian temple, gladiatorial shows and wild beast hunts. By Galba's time it was coining for itself. Finally the Gauls dropped the tribal name, first at the ancient temple city of Pessinus. Even in Paphlagonia early urbanization is attested by the name of Caesarea of the Proseilemmenitae.[796]

iv. consolidation under the julio-claudians

The stable conditions created by Augustus required his successors to be maintenance engineers in the provinces, adjusting his scheme rather than making radical alterations, and his immediate successor Tiberius firmly professed close adherence to Augustan precedent. But the accession of a new emperor, even one well known in the East as Tiberius was (he enjoyed divine honours at Nysa by 1 B.C.) and for ten years the designated heir, a period in which he was being courted even by relatively unimportant cities such as Aezani, inevitably caused a stir. The new man could have new friends and favourites; relationships have to be developed or entered into. So in the Peloponnese, where the Claudii had hereditary influence, the League of Free Laconians in 15 passed a sacred law establishing ceremonies in honour of Augustus, Tiberius, Livia, Germanicus and Drusus, as well as for T. Quinctius Flamininus and the two local dynasts Eurycles, now posthumously rehabilitated, and his son Laco, who may have been particular partisans of Tiberius; Laco continued in favour for another nineteen years. At Paphos on Cyprus the people were quick to take an oath of loyalty to Tiberius and his blood line. From the beginning of the next reign there survives another oath taken at Assos in the Troad, in which play is made with Gaius' childhood visit to the city nearly twenty years previously. At Cyzicus Gaius accepted the local magistracy, the hipparchy, and was designated the 'New Sun'. These were prudent measures: Gaius had his own ideas about his position in the empire, different again from Tiberius'.[797]

Ironically, in view of his publicly proclaimed adherence to the Augustan blueprint, it was Tiberius who in the earliest years of his reign made significant changes in two of the regions with which we are concerned. The answer that Tiberius and the Senate returned to the request from Macedonia and Achaea for transfer to imperial rule was favourable but unflattering. Instead, economy was served: the two provinces were to have no governor of their own, but were attached to the province of Moesia. (Already in a.d. 6, when the proconsul died in office, his province had been divided between his quaestor and his legate.)[798] But the change brought into the open the fact that Macedonia and Achaea were backwaters removed from the scene of action nearer the Danube.

The unification was followed by the amalgamation of the two main leagues. The enlarged koinott (called variously Panachaean, Hellenic and Panhellenic) went back at least to the end of Tiberius' reign and consisted of representatives of Achaea proper, which itself incorporated a koinon of the Argolis under Augustus or Tiberius, Boeotia, Locris, Phocis, Doris and Euboea;60 a number of cities and lesser leagues, such as the Eleutherolacones and Thessalians, were not included. The Greek koina were not as alert as the organizations of Asia and Bithynia — areas that had been directly controlled by monarchs since the time of the Persian Empire - to the value of offering cult, but they eventually did so, electing a high priest as well as a political leader; the earliest signs are Neronian at latest, the official C. Iulius Spartiaticus, a descendant of Eurycles and, like all the high priests, a Roman citizen.61

The new arrangements lasted until 44, when Claudius returned Achaea to the jurisdiction of ex-praetors selected by lot.62 So it remained until Nero, claiming to be the only emperor who was a philhellene, conferred freedom on Greece on 28 November, probably 67 rather than 66, during his performing tour of the province.63 It was a reiteration (not the first) of Flamininus' declaration of a quarter of a millennium previously, but the Greeks appreciated the gesture of recognition and the abolition of taxes that went with it. Even in Plutarch's view, that of an upper-class intellectual in full sympathy with senatorial opinion, freeing those who were 'noblest and dearest to the gods' earned Nero reincarnation as a singing frog rather than as a viper.64

Nero's cultural philhellenism was genuine and strong. It too was appreciated. The tour he made (the four great festivals, Pythian, Olympic, Isthmian and Nemean, were rescheduled so that he might compete in all) was the first personal visit from a member of the imperial family since that of Germanicus and Agrippina, when Germanicus had a commission similar to those previously held by Agrippa, abortively by Tiberius, and by Gaius Caesar. The respect that Germanicus showed at Athens in 18, when he visited it after Nicopolis, was set off by the brutal assertion of Roman supremacy by his coadjutor Cn. Piso.65 Tiberius himself was a cultured philhellene and Athens' benefactor before his adoption, although Livia apparendy attracted more attention than the emperor. Surprisingly enough Claudius won more dedications than Nero, more than any emperor between Augustus and Hadrian. A whole

40 GCN 361, with Kahrstedt 1950 (e 846) 7of. « GCN 264.

62 Suet. Claud. 25; Dio lx.24.1.

a GCN 64. For 67 as the year see Griffin 1984 (c 352) 280, n. 127. м [Plut.] Мог. 567f.

65 Tac. Anп. II. 3 j.:.

series honours him as Saviour and Benefactor: probably he paid for stairs leading to the Propylaea, not only adorning the Acropolis but providing work for quarrymen and craftsmen.66 Nero contributed a new skene for the Theatre of Dionysus, which was dedicated to Dionysus Eleutherius and to the emperor, whose priest and high priests were reserved front row seats.67 But Nero could not free Athens along with the rest of Greece: freedom was a privilege she already enjoyed.

The reign of Tiberius, like the last decade of Augustus' Principate, had to be one of retrenchment in Italy and perhaps elsewhere. Areas self- sufficient and exporting would suffer less. Asia and Bithynia came into that category, as building activity during the reign suggests; Crete too. Parts of Achaea already in decline did not: at the end of the reign, Boeotia claimed not to be able to afford an envoy to congratulate Gaius on his accession.68 Some insight into the collection of taxes - and into the difficulties that some cities encountered in meeting their obligations - is given by inscriptions from Messene and Lycosura.69 And Achaea's capital, artistic and financial, was diminished when Nero's agents began to scour the provinces for works of art in a systematic effort quite different from the haphazard acquisitiveness of Verres or Antony. The centres of Greece and Asia known to have suffered were Athens, Delphi, Olympia, Thespiae and Pergamum. At Athens the imperial agent C. Carrinas Secundus was made eponymous archon, as if to blunt his zeal.70 There was a certain irony in Nero's regret, expressed when he freed Greece, that he could not do it at a time when she was at her peak - though his generous act sprang from good will, not mere pity.

A recurrent, even chronic problem was shortage of grain, which had to be countered at any cost. Even in Asia Minor, where grain was a staple product, a severe winter could cause difficulties, especially in cities distant from the sea, where importing supplies would be particularly expensive. Aspendus in Pamphylia is not far from the sea, but vetch is said to have been on sale in place of grain there on one occasion under Tiberius. One of the titles accumulated by Agrippina on her travels with Germanicus was that of Divine Harvest-bringer, Aeolis, at Mytilene, like her daughter and namesake who took a place in the imperial pantheon on Cos as Demeter Harvest-bringer and was shown on city coinages with corn ears and poppies — similarly too on a panel from the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias. The divinities would hardly allow their votaries to go hungry.71

66 IG ii2 5269, j27if, 3274. See Shear 1981 (e 873) 367, n. 52. « IG ii2 5034.

<* GCN 361. « ICv 1.1432; 2.516.

IG ii/iii2 4188, with Graindor 1931 (e 853) uf.

Aspendus: Philostr. VA 1.15; Mytilene: ILS 8788, IG xii 2.258, with L. Robert, REG 72 (i960) 286ff. Cos: A. Maiuri, Nuwasillogeepigr. (Florence, 195 2) 468; coins: BMCLjdia 146, nos. 5 35 (Magnesia by Sipylus); Aphrodisias: JRS 77 (1987) PI. VIII.

Greece was more accessible by sea than the interior of Anatolia, but there were still questions of procurement and distribution, and of the cost of the operations. Athens had been importing corn since the time of Pisistratus; there was no imperial revenue to pay for it under the Principate. A special treasury for the reception of grain was created there in the reign of Augustus, significantly perhaps under the supervision of no less an official than a hoplite general. Under Claudius the curator annonae appears at Corinth, and on one occasion there was a famine in Greece that took a modius of grain to a price of six didrachms, about eight times the normal price at Rome.[799]

The other natural calamity to which both Greece and Asia Minor are subject is earthquakes. The Roman government did its best to help wherever they struck. One night in a.d. 17 twelve distinguished communities of the Hermus basin in Asia fell victim. Sardes suffered worst and was granted five years' remission of all taxes as well as a gift of 10 million sesterces from the emperor; Magnesia by Sipylus was held to have suffered next worst and was compensated accordingly, while the rest were relieved of tribute for five years and a commissioner was sent to inspect the damage and help restore it. Six years later it was Aegium, centre of the Achaean League, and Cibyra, an assize centre of Asia, that were devastated and granted three years' remission of tribute on the initiative of the emperor.[800]

This generosity, and his pitiless atdtude towards officials who enriched themselves at the expense of provincials - a proceeding that the people of Asia must have come to regard as almost as inevitable as natural calamities — won Tiberius popularity; on both fronts he was following the example of Augustus. The coming of the Principate did not destroy the hereditary connexions that families such as the Messallae, Galbae and Pisones had with the East and their natural claim to serve there, any more than it eliminated the expectations of some senators that they could reimburse themselves for the cost of attaining office in the course of their pro-magistracies and even make a profit. The wealth of Asia was a particular temptation, especially when the fortunes of Italian senators were in decline. Fierce competition for the province is attested in the twenties and thirties, made fiercer by Tiberius' proneness to prolonging even strictly annual terms of office: P. Petronius held Asia for about six years, c. 29—35; a C. Galba, excluded in 36, killed himself.[801]Envoys even from Achaea had complained about their governors even under Augustus, but the series of known prosecutions for misconduct in Asia begins with a particularly outrageous case, that of Valerius Messalla Volesus, who during his proconsulship of about 1011 had not only enriched himself but done so with open brutality, stalking amongst the corpses of 300 men he had executed and preening himself on a right royal deed. The case of Granius Marcellus, the proconsul of Bithynia prosecuted in a.d. 15, was unsensational, but Tiberius' handing over of his procurator in Asia, Lucilius Capito, for trial in the Senate in 2 3 made history and, like the relentless handling of C. Silanus on the precedent of Volesus the year before, won the emperor high opinions in Asia.[802]

These were the first attested prosecutions conducted at the instance of the koinon of Asia, which lost no time in securing permission to erect a temple to Tiberius, his mother and, Tiberius insisted, the Senate. It was not until three years later that Smyrna, which had celebrated the cult of Rome since 195 B.C., was selected from eleven contestants as the site. When it came to Gaius, Miletus was successful;[803] but by no means all emperors were honoured in this way: both Claudius and, more surprisingly, Nero were omitted. But a city of the first rank such as Ephesus might become 'warden' (neocorus) of no fewer than three imperial temples as well as that of its own patron deity. By at least eleven cities too Tiberius was honoured with cult, becoming 'the greatest of the gods' at Cyzicus.[804] After him emperors tended to be objects of cult from the koinon en bloc, but within this limitation cities went on doing what they could to attract favourable attention by demonstrating loyalty.[805] Their efforts were not always well judged: what was a community in Lydia doing with a public area commemorating Gaius' German campaign, and why should Amisus in Pontus be honouring Nero, Poppaea and Tiberius Claudius Britannicus on the same monument?[806] It was a different matter when a sophisticated polis with long-standing connexions with Rome, such as Aphrodisias, embarked on the construction of a Sebasteion with a processional way between porticoes leading to a raised temple and of proficient sculptures adorning the complex.80

The princeps himself was a powerful neighbour to many ciues and individual landowners as he acquired estates, mines and quarries by purchase, inheritance, or confiscation, or controlling them in virtue of his role as governor. Patchy at first, especially the reladvely isolated quarries, his estates in Asia Minor were to form large tracts of territory in the second century. Lucilius Capito's encroachments on the prerogatives of a governor illustrate the growing importance of officials charged with administering the imperial property and the recognition they were being accorded. Under a governor of less than the highest seniority or calibre, such as the proconsul of Bithynia, the procurator's responsibilities and his prestige might eclipse those of the pro-magistrate. East-West communications and increasing wealth made Bithynia more important than it had seemed under Augustus: the princeps would not leave it all in the hands of the proconsul. Iunius Cilo, procurator at the end of Claudius' reign, managed imperial business there and escorted a deposed monarch to Rome in 49, winning consular decorations. His subjects brought charges of extortion against him but he was acquitted and apparently prorogued. The services of Publius Celer, procurator of Asia when the Principate changed hands in 5 4, were political, the murder of a potential rival of Nero; it was they that saved him from accusations levelled against him by the provincials, at least long enough for him to die a natural death. By contrast a determined citizen of Cibyra, which under Claudius was temporarily detached from Asia and assigned to Lycia, was able to have an oppressive procurator removed from his duties of collecting grain from the city.[807]

Political considerations were also important in the trials of senators charged with misconduct. Only the most strenuous efforts secured the conviction of Nero's man Cossutianus Capito in 5 7 for misconduct in Cilicia; the valuable prosecutor Eprius Marcellus, charged with repetun- dae in the same year, was acquitted, secured the exile of some of those who had accused him on behalf of the Lycian koinon,[808] and lived to return to Anatolia under Vespasian for a three-year term as governor of Asia.

When Germanicus travelled the coasts of Greece and Asia Minor in 18, he worked to restore places exhausted by internal disputes and mismanagement on the part of their own magistrates.[809] Having paid to secure the positions they held, members of the ruling class in the cities sought to recoup their expenditure. This was a failing that Aristotle remarked in timocracies such as the Romans favoured, and the venality of Greeks was already commonplace for Polybius and Cicero.84 A Claudian proconsul of Asia, Paullus Fabius Persicus, issued a long and elaborate edict curtailing (he hoped) inefficiency, waste and dishonesty in the administration of the temple funds established by Vedius Pollio for the cult of Artemis at Ephesus.85 One trick was to lend young slaves to the temple, where their upkeep would be paid; another to anticipate temple revenue and speculate with it.

Paullus was a friend of Claudius and knew what was expected of a governor. Others became involved with local malefactors, giving them protecdon and an opportunity for blackmail. Those who did not cooperate could be threatened with the prospect of being passed over when it came to votes of thanks for their administration. Augustus had already in a.d. 12 forbidden such votes to be passed within six months of a governor's departure (perhaps in the wake of the Volesus Messalla case). The abuse came to light most blatantly in Neronian Crete, where the leader of the koinon, Claudius Timarchus, boasted that it depended on him whether governors were given votes of thanks. The dispatch of embassies to express such thanks before the Senate was now banned altogether - for a time.86

In Crete it seems that the koinon had acquired a particular ascendancy in relation to the individual cities, whose coinages ended under Gaius and were superseded by that of the koinon (in Cyprus too the currency became federal). In spite of the failings of city and koinon officials, which could not be cured and were to develop further (the history of Crete under the Julio-Claudians has been called a recital of earthquakes and trials for extortion; encroachment of magnates on city land is another failing detectable there),87 the Romans had no alternative. Koina were a prime means of conveying instructions to the leading men of a province, of focusing their loyalty and satisfying their ambition. Private clubs were banned from the time of Caesar and Augustus onwards, as attracting the lower classes in the cities and otherwise likely to turn into radical political groups; exceptions were allowed only for those exclusively religious and social in character, and they had to be licensed. Associations of boys (ephebes), young men (neoi), and elders {gerousiae), which were integral parts of the city, and professional associations of men of respectable standing were a different matter. In 41 the Guild of Hymnodoi of Asia - choruses who performed at the celebration of the imperial cult - had occasion to honour Claudius and the privileges of stage artists (the World-wide Guild of Crowned Victors in the Sacred Contests of Dionysus and their Fellow-competitors) had already been granted by Augustus before Claudius guaranteed them in 43 and 48-9. Athletes too, as Antony's letter to the koinon shows, had long been recognized as a group with legitimate interests and the Itinerant Athletic Association was careful to inform Claudius in 47 of the successful festival held in his honour by the kings of Commagene and Pontus.88

As to the success of the provinces of western Asia Minor as a whole, the Romans can have felt no misgivings. They continued to encourage

" Tac. Ann. xv.20-2; for Augustus, see Dio lvi.2j.6.

" See Sanders 1982 (e 871) 132; encroachment: GCN 385; 388.

и GCN 372 (bjmnodly, 375 (a) and (b) (Dionysiac artists); EJ2 300 (Antony's letter); GCN 374 (the Claudian festival).

communities who aspired to polis status. Besides restoring damaged cities Tiberius allowed two to take his name: one Tiberiopolis was in Phrygia Epictetus, the other (Pappa) in the Galatian province, on the borders of Phrygia and Pisidia: within the greater cities both Aphrodisias and Pisidian Antioch had squares named after him.

But it was in eastern Asia Minor, in the third of the regions with which we are concerned, that Tiberius made his most important changes in the Augustan political map. Germanicus' mission to the East in 17-19 had two main positive purposes: to deal with the Parthians and to establish a new Roman client on the throne of Armenia Maior. But the visit came at a time of change for long-standing client states: the deaths of Antiochus III of Commagene, of Philopator in the kingdom of the Amanus, and, at Rome where the princeps had summoned him to stand trial before the Senate (he had faced charges from his subjects on an earlier occasion), that of the aged Archelaus of Cappadocia.[810]

Tiberius made a clean sweep of the client kingdoms. The 8 5,000km2 of Cappadocia, with its eleven eastern-style 'satrapies' — strategiae in Greek - — and its few cities concentrated in the most westerly of them, required direct rule. After the preliminary arrangements had been made by a legate of Germanicus, Q. Veranius, the new province was entrusted to an equestrian prefect. To make Roman rule more acceptable, taxes were reduced, but even so Tiberius was able to halve the 1 per cent inheritance duty on Roman citizens. Commagene was taken over by Q. Servaeus, another legate, and, like the kingdom of the Amanus, incorporated in the province of Syria. Only Pythodoris, undl her death,90 Archelaus' son in part of Cilicia Tracheia, and the Teucrids of Olba were left in place, and Olba came to be overshadowed by a new foundation of uncertain date, Diocaesarea. As far as Cilicia was concerned, it was a wise decision: the younger Archelaus' subjects, the Citae, were sdll giving trouble in 36, when they refused a census and all its implications, and in 5 2.91 But some of Tiberius' arrangements were reversed by Gaius, a true great-grandson of Antony who had been brought up at court with eastern royalties. In 3 8 he returned Commagene to Antiochus (IV), with the addition of eastern Cilicia, and Pontus to Polemo (II) who also acquired the Teucrid kingdom when the dynasty died out in 41. Antiochus kept his kingdom, with one interruption, until 72, Polemo his until 64, when it was annexed as Pontus Polemoniacus. Gaius assigned Armenia Minor to another friend and grandson of Pythodoris, Cotys. Whatever his motives, it is usually agreed that the territories he assigned to clients were well suited to that form of government; how potendy his actions were felt in the Greek East, is attested by a decree of Cyzicus: 'Since the new Helios Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus wished also to illuminate with his own rays the kingdoms that are the bodyguard of the empire ... even though the kings, however hard they think, are unable to find appropriate ways of repaying the benefactions conferred on them to show their gratitude to so great a god, he has restored the sons of Cotys (VIII of Thrace), Rhoemetalces (III of Thrace), Polemon and Cotys, who were brought up with him and were his companions, to the kingdoms that were due to them from their forefathers and ancestors. Reaping the abundance of his immortal grace, they are greater than their predecessors in this respect, that they inherited from their fathers, while these men, as a result of the grace of Gaius Caesar, have become kings to share in the government of these great gods.' Small wonder to find Tryphaena, mother of the kings, in the same document celebrating the cult of Drusilla the New Aphrodite, and Polemon jointly celebrating the games with Andochus IV.92

But Gaius' donations went against the trend. In 43 direct Roman rule spread to the south-west corner of Asia Minor when mountainous Lycia, with its thirty-six cities — the earlier number considerably advanced since the assessment of Strabo - was annexed, Rhodes also losing its freedom in the following year. Claudius' pretext was disorder in the cities and the killing of Roman citizens, but he allowed an appeal from Rhodes, backed by the young Nero, in 5 3,93 As far as Lycia's external independence went the change was a nominal one; cult had been offered since 188 B.C. to Roma Thea Epiphanes and to powerful Romans such as Agrippa; Tiberius' cult survived until the third century alongside the federal cult of the Augusti.94 But the federated cities now had to pay tribute and the first praetorian legate, Q. Veranius, doing for Claudius what his father had done for Germanicus in Cappadocia, seems to have met resistance.95 To loyal subjects Veranius was able to offer the reward of citizenship, and the new province settled down with Pamphylia, the district joined to it under the new arrangement, its upper class crystallizing into a nobility of Lyciarchs and (at least from Vespasian onwards) high priests, who often served as secretaries of the League, with archiphylax and hierophylax to guarantee order and collect the tribute. If we are to trust Suetonius, Lycia regained its freedom some dme before Vespasian's reorganization of the eastern provinces, either from Nero, after the freeing of Achaea, or under Galba; but epigraphic evidence suggests that Lycia had a governor who survived from Nero to Vespasian.96

Dio Lix.8.2; lx.8.i (Antiochus). Braund (c 254) 42, on lx.8.2 (Polemo); Suet. Ner. 18, with Magie 1950 (e 855) 1417 n. 62 (annexation of Pontus Polemoniacus). GCN 401, with Price 1984 (f 199) 244f (restoration of the three monarchs).

Dio Lx.17.}; 24.4; Tac. Ann. xn.58.2. Pliny, HN v.ioi (number of Lycian cities).

Rome: SEG xviii 570; Agrippa: IGRR in 719; Tiberius: 474; high priests: 487.

93 GCN 2} i (c).

96 Suet. Vesp. 8.4, but see W. Eck, Senatoren von Vespasian bis Hadrian (Vestigia ij) (Munich, 1970) 4.

It was under Nero that the main structural change in eastern Asia Minor came. Made in 5 4 for military purposes, it provided Cn. Domidus Corbulo with freedom of action against the Parthians and a wider recruiting ground amongst the warlike Gauls, and it became the model for Vespasian's permanent scheme. Cappadocia and Galada were united under the consular legate Corbulo, and his routine work in remoter areas was performed by a separate legate.97 The strategic importance of eastern Asia Minor was being realized; if its wealth was also increasing, that was a process that would be speeded up under the Flavians.

The client monarchs prepared for their own supersession by following the tradition of their kind and founding cities. M. Antonius Polemon of Olba may be the founder of Claudiopolis on the Calycadnus; Antiochus IV founded Germanicopolis, Andochia ad Cragum, Iotape and Neronias, later the city on the main road to Caesarea from the west that Archelaus made from the typical 'village-town' or 'fortlet' Gar- saoura, administrative centre of the strategia named after it; it became a colony under Claudius. Urban development is suggested elsewhere in the south-eastern sector of Asia Minor by the appearance of city names compounded, as before, with those of the emperors, but how substantial any accompanying changes may have been is not clear. Certainly the reigns of Claudius and Nero saw road construction and repair in Anatolia: in Asia (the road from Smyrna to Ephesus and Tralles in a.d. 51), Pamphylia (under the imperial procurator in 50), Bithynia (the Apamea-Nicaea route in 57-8) and Paphlagonia (c. a.d. 45 near Amastris).98

v. conclusion: first fruits

The century between Octavian's accession to sole power and the death of Nero was one of almost unbroken peace in the areas under discussion, a condition ideal for political and economic development for regions capable of it. Western Asia Minor was in the van, in part because of its proximity to the new Danubian provinces of Moesia and Pannonia, in part as encasing the routes that led from Ephesus and Byzantium through the Cilician Gates into Syria or by more northerly branches to the Euphrates crossing at Tomisa. From this last factor, proximity to main lines of communication, central and eastern Asia Minor also benefited, especially communides that lay on the highways, such as Ancyra, Iconium and Caesarea Mazaca.

From the Roman point of view increased prosperity meant an increase in the amount of tax that the regions would yield and, almost equally

« GCN 244.

" Asia: CIL hi 476, 720; Pamphylia: GCN 347; Bithynia: CIL 111 346; Paphlagonia: ILS 3883.

important, their contribution to manpower at all levels. It is significant that in spite of the obstacles in the way of easterners (language difficulties, prejudice against new men) a beginning was made during this century in recruiting men to the imperial service which culminates, in the Neronian period, in the admission of a considerable number of easterners into the Senate.

Grants of citizenship were the prerequisite, and the rate of progress varied from city to city and province to province. From actual or, at a pinch, potential citizens, legionaries might be recruited, but even non- citizen areas could contribute soldiers to the auxiliary forces. For these the places of origin are significant: no units bear names that show them originally levied in Achaea, Bithynia, or Asia. Levying a troop of horse or auxiliary infantry from freshly provincialized territory would be removing potentially dangerous manpower from its home area, and some units at least (notably numeri and those with specialized weaponry) continued to be drawn from their original recruidng grounds even after they had moved; this was not a motive that would apply in the two western regions, Greece and the proconsular provinces of Asia Minor. But mountainous Crete provided a cohort, Galatia apparently an ala (VII Phrjgum), and Cyprus four cohorts."

Achaea equally fails to turn up any legionaries in this period, an indication of impoverishment: recruiting officers perhaps did not think it worth visidng. Asia and Bithynia have seven to show, eastern Asia Minor eight times as many (with the three Gallic capitals contribudng over half), and Roman colonies such as Troas, Antioch towards Pisidia, and Ninica seven. Potential fighting quality and a stake in the land were desiderata fulfilled above all by men from military colonies and apparently by the Gauls.[811]

At a higher social level the picture changes. Equestrian procurators had to satisfy a census requirement (400,000 sesterces) and high qualities of character were expected.101 These were conditions not different in kind from those applied to legionaries, but for equestrian posts patronage and recommendation played a vital part and men from out of the way places did not stand a good chance. Pompeius Macer of Mytilene, procurator of Asia and librarian at Rome already in the time of Augustus, came of a family that had been close to the Roman dynasts since the middle of the first century в.с. С. Iulius Spartiaticus, son of the disgraced Laco and grandson of Eurycles, became a procurator of Claudius and Agrippina; not surprisingly he claims to be 'first of the