Apart from a reference to a census,58 only a few anecdotes survive about Gaul in Nero's reign. A statue of Mercury was built among the Arverni and there was a fire in Lyons in a.d. 65.

Some general observations emerge from this brief survey. For most of the period, the major events centred on the north east where tens of thousands of troops were stationed, an equivalent population, in ancient terms, to that of a number of cities. The troops acted as a huge economic magnet but also a political magnet in so far as emperors and members of the imperial household visited the area frequently. The other region affected by military activities at this period was Aquitaine, in the narrow sense of the area south of the Garonne. Agrippa's road system, decided on very early but constructed over a long period of time, accorded importance to both the north east and the south west. Finally, regardless of misinterpretations of the events of a.d. 21, the strong links established by Caesar between the 'Julian' aristocracies and the imperial power showed no signs of weakening.

2. Innovation and inertia

Attempts to assess the impact of the conquest and of the imposition of new structures on Gaul run up against a major problem. On none of the sites that were to develop into Gallo-Roman towns, are there any archaeological levels datable to the period between the end of the Gallic Wars and about 20 B.C., or even later. The most striking examples are the three colonies founded by Caesar and Plancus. At Nyon, the colonia lulia Equestris, nothing has been found dating from before 15 b.c., at Augst, Augusta Raurica, the earliest levels date from the end of the reign of Augustus and at Lyons the first traces apart from defensive ditches, perhaps those of Plancus' camp, date from between 30 and 20 B.C. Dendrochronology has dated the first encampment at Petrisberg in Trier to 30 b.c., but there is no contemporary material. The few exceptions are often ambiguous. There have been a few sporadic finds at Reims, where two ditched and banked enclosures have been found, remains of settlement are known from Metz, thousands of Gallic coins have been found at Langres and the excavations of 'ma Maison' at Saintes in the south west, have produced some sherds of 40—30 B.C.

Should we conclude that the first towns took their time to appear? In fact, the argument ex silentio should be distrusted for two reasons. The first reason is that urban archaeology is a relatively recent innovation in France. The second is that, when it comes to these early periods, the stratigraphic frame of reference depends on finds from Roman military camps, and the earliest camps to have been excavated date from after 19 в.с. Neuss is dated after 19 B.C., Dangstetten from 15 to 9 B.C., Rodgen between 12 and 9 b.c., Oberaden between 11 and 9 b.c., Haltern from 7 b.c. to a.d. 9 and so on. The result is that archaeologists are often unable to date material that is after 50 b.c. but before 20 b.c., especially if the material does not consist of imported pottery. It is quite likely, then, that research will advance rapidly in this area, but for the moment it is only possible to stress the slowness of developments.

The birth of urbanism can only be traced from the Augustan period, and then only from the end of his., reign, since almost every town site produces sherds of Arretine ware and then of early Gaulish terra sigillata. It is important to distinguish several categories among these sites. For a start we must set to one side the cases of Lyons and of Autun. Lyons grew enormously from 20 B.C. onwards. Although it was doubtless unfortified, the hilltop of Fourviere was covered with settlement, a theatre was built there with stone imported from quarries in the south, in particular from Glanum, and there was probably a forum too. Craft workshops developed on and around the hilltop, and branches of the great pottery manufacturers of Arezzo, Pisa and the north of Italy, were set up there to supply the Roman military camps. From the Augustan period they even imitated amphorae of Dressel2-4 type and several other varieties. Lyons became a distribution centre for Mediterranean products including wine, olive oil and fish preserves en route to Switzerland, the Moselle valley and the Rhineland, not to mention central and western Gaul. After the federal sanctuary was set up at Condate in 12 B.C., euergetism increased and more and more monuments were built, like the amphitheatre, given by aristocrats from Saintes in a.d. 19. Lyons became a political, religious and economic metropolis adorned with a striking array of monuments. The first houses were built of wooden panels, had several rooms, floors made 'en terrazzo' and wall-paintings inspired directly by Roman fashions.

The case of Autun is rather different. The late Iron Age capital of the Aedui had been Bibracte, mentioned several times by Caesar who had stayed there. It was located on the summit of Mont Beuvray, some 20 km from Autun. Excavations in the nineteenth century, which have recently been resumed, uncovered public zones, a wide variety of private housing, including some huge houses of Roman design, and artisan quarters, all surrounded with a massive rampart. The whole town was moved to Autun, and the population transfer must have been fairly rapid as the finds from Bibracte hardly go beyond the turn of the millennium. The name Augustodunum expresses Augustus' desire to bestow his personal favour on Rome's oldest allies. Plenty of other evidence shows his favour in action: Autun was surrounded by the only circuit wall built in the Three Gauls in this period, crowned with towers and adorned with four ornamental gates, enclosing an area of some 200 hectares. Autun was also the home of the famous 'universities' for young aristocrats from

all over Gaul, and of the school for gladiators. Built from scratch with a regular orthogonal street plan from the first, Autun was the showpiece city. The city drew its livelihood from the elite who lived within its walls, but drew their wealth from the land. Craftsmen were attracted by the city's position at a natural crossroads, and Autun probably had great religious prestige, as the sacred quarter based around the temple of Janus shows. But the town never really took much part in the great commercial movements which were the lifeblood of Macon and Chalon. The early prominence of the city derived from a desire for an urban lifestyle, based on the integration of the elite and on practical assistance from the Roman authorides, perhaps in the form of tax exemptions or gifts.

Other towns in Gaul had very different experiences. In Switzerland, orthogonal grids were laid out at the very start, and filled in little by little by buildings constructed of wood and earth. Spaces were reserved for public use, but monuments were rare: Augst was partly enclosed by a circuit wall and had a theatre and Nyon had a building of basilica-type. It is possible that the colonial status of Augst and Nyon exerted an influence on other centres like Avenches.

The road network must also have played a part. For some time now, excavations in the towns on the main route to the south west have been revealing Augustan layers and Augustan street grids. These are towns like Limoges and Clermont-Ferrand, the Roman names of which alone suggest an early origin.59 Recent discoveries at Feurs, Roman Forum Segusiavorum, support this picture, revealing an Augustan street plan, a forum dated to around a.d. 10—20 and an inscription attesting a wooden theatre.60 So although the unrest in Aquitaine had been settled fairly early on, the route to the south west continued to promote urbanism.

The same applied in the north east and the east. Langres, Metz, Trier and Amiens all grew up at key points on the road system. So too did less important centres like Bavai, or nearby sites like Paris. When the road junctions were also on navigable rivers, towns developed even earlier and became even more important. For example, Amiens had a town grid based on the pes drusianus, and its wattle and daub buildings covered an area of 40 hectares. Trier, Metz and Reims were probably broadly similar. Craft activity is well attested but no sign of public monuments.

Almost everywhere else is it difficult to reconstruct the earliest stages of town life. The best known of the towns of the south west is Saintes, Mediolanum Santonum. The town is famous for the family of Iulii descended from the Gaul Epotsoviridus, whose great-grandson C. Iulius Rufus built the amphitheatre of the Three Gauls at Condate, and in a.d. 18 or 19 put up the arch of Germanicus in his own city. But the Augustan town itself is haphazardly laid out, with tiny winding streets and both houses and workshops built of wattle and daub and only 20 to 30 square metres in size.

At Bordeaux, the late Iron Age 'emporium' covered an area of at most

A number of Gallic towns had names beginning in Augusto-, for example, Autun, Clermont, Limoges, Troyes, Bayeux and Senlis; in Caesaro-, for example,Tours and Beauvais; or in Iulio-, for example, Lillebonne and Angers. In other cases the element Augusta was followed by the name of the people, as in the cases of Trier, Saint-Quentin, Soissons and Auch. The names might have been granted as a favour at any point during the Julio-Claudian period.

CIL xm 1642. A civic benefactor, of the reign of Claudius, announces that he has rebuilt in stone a wooden theatre.

5 or 6 hectares on a promontory surrounded by soft ground on the banks of the Garonne. The Roman conquest had no impact on the site until the beginning of the Christian era. At the end of Augustus' reign and the beginning of Tiberius' the city expanded outwards to cover some i г to 15 hectares, and the first traces of regular town-planning and Roman building techniques appeared, but the main period of expansion did not start until the middle of the first century. Much the same sort of sequence could be described for a number of towns, from Poitiers and Perigueux to Avenches and Trier. As for Brittany, Normandy and the Loire valley, all that can be said is that the remains are very slight.

To put it another way, perhaps we should imagine many of the civitas capitals of the Three Gauls as sparsely populated centres, only roughly planned out, with a few clusters of public buildings, maybe wooden ones at that, a little trade going on, a few craftsmen and houses built in much the same way as in the late Iron Age.

Epigraphy and architectural elements can be used to elaborate the picture a little, although there again the evidence concentrates in Switzerland, in the north east and in the south west. At Langres, a text refers to a temple of Augustus vowed by Drusus in 9 в.с. The Princes of the Youth received epigraphic or monumental honours in Lyons, Sens, Trier and Reims, where there was a cenotaph. In 4 в.с. Bavai, Bagacum, acclaimed the adventus of Tiberius. The columns and capitals found at Saintes and Perigueux follow Roman models from the end of the last century B.C., and in Switzerland sculpture was made and imported from the reign of Augustus. It is worth bearing in mind that many buildings, including basilicas, theatres and amphitheatres, may well have been built in wood, on the lines of those we know of from the military camps, and so would have left no trace. All the same, with the odd exception, the Three Gauls had not produced a thick crop of towns in the Augustan period. The contrast with the situation in Narbonensis is striking.

The forty years between the accession of Tiberius and the death of Claudius corresponded, in most of the towns discussed above, to a period of growth and monumentalizadon. The street plans were systematized and in many places, especially in Switzerland, masonry began to be used. The first trunk roads were built, like that linking Saintes, Poitiers and possibly Paris. Amphitheatres were built at Saintes, perhaps at Senlis as well, and in Perigueux, where it took the family of the Auli Pompeii, whose first member was called Dumnotus, three generations to complete the task. Public baths were constructed, aqueducts were built as at Bordeaux, and houses were bigger and decorated with wall-paintings based on the Pompeian Third Style. At Lyons, excavations at the site of le Verbe Incarne show that the plateau of la Sarra was levelled to allow the building of a temple, surrounded with porticoes resting on cryptoporticoes, and dedicated to the imperial family. Also at Lyons, a monumental fountain, supplied with water by a new aqueduct, was dedicated to Claudius and a major programme of reclamation made the tongue of land between the Rhone and the Saone habitable and suitable for a trading district.

New towns appeared and others expanded to become real urban centres most of all as a result of greatly improved communications, affecting many regions but especially the west. Claudius' reign witnessed large scale road building projects, especially in the Loire valley, but also supplementing road networks in the north, the centre, Brittany, Normandy and elsewhere. The conquest of Britain stimulated development all along the Atlantic strip. This was also the period of the great expansion of Poitiers and Bordeaux, as well as of the growth of Tours, Bourges, Angers, Rennes as well as of many other centres which would not all become quite so successful.

Why was it that urbanization was such a slow and often such a limited process in the Three Gauls? The Celtic oppida do not seem to have been intensively occupied for very long after the conquest, in fact one of the most recent contributions of archaeological research to the debate has been to show the early origins of many of the secondary urban centres which comprised the closely packed network of sites usually termed vici. Some originated when populations moved down from hilltop sites to the neighbouring plains, others developed from indigenous sites of similar scale which were rarely located on hilltops, despite the famous example of Alesia, but many seem to have been created ex nibilo. Apart from those sites that developed around places of pilgrimage, these vici tended to be located on routes, whether terrestrial or riverine, that had been important ever since the Neolithic period, in other words astride those communications channels that had organized local life from time immemorial. Almost everywhere in the Three Gauls these small centres have produced evidence of craft working, often at quite a sophisticated level, including bronze and iron working, carpentry, weaving and pottery production. The small towns had a commercial role, then, sometimes directed towards a military camp, as in the case of the canabae of Mirebeau or Strasbourg or Baden in Switzerland, but more often serving a local catchment area. Early on some of these vici were planned and acquired some public buildings. Vidy, Lousonna, had a street plan from 20—10 в.с. and a building with a basilical plan was constructed there round a.d. 30-40; Alesia and Malain were planned under Augustus and organized properly under Claudius, Alesia acquiring streets, porticoes with fafades, masonry buildings, temples and a square. Some of these towns were more dynamic than the cities that were the capitals of their civitates-. Orleans, for example, grew much faster than Chartres. The first land divisions discovered by aerial photography show that Three Gauls did not exhibit the same strong links between cities and their suburban and rural villae as characterized Narbonensis. Town and villa relations were much more typically centred on the vici.

Does this mean that, in general, apart from those regions affected by colonization and perhaps by proximity to Narbonensis, the Gallic landscape was structured not so much by the new constraints introduced by Roman rule, but by longer term factors? We need to know more about these long-term structures before that hypothesis can be assessed and the notion of 'tribal survivals' should be shunned. But it does seem likely that the influence of the local territories predominated over the impact of the Roman civitates.

Unifying factors

The Latin right had been granted to all communities in Narbonensis in the Caesarian period, and although some juridical complexities had been introduced by granting some civitates treaties or Roman citizenship as privileges, a general principle had been established. In the Three Gauls, on the other hand, the principle was one of diversity. We can reconstruct from various sources, and in particular from Pliny, the list of states with treaties. It comprises the Helvetii, the Carnutes, the Remi, the Aedui and the Lingones. But it is much less clear which cities were free, (liberae) and which exempt from taxation (immunes), and the epigraphic evidence does not always agree with the literary sources.[648] Strabo states that Rome had granted the Latin right to some Aquitanian peoples, 'in particular the Ausci and the Convenae'.[649] This may have been on the occasion of the Pyrenean campaigns or possibly it was because the Convenae had once been included in Gallia Transalpina. Other civitates were granted the Latin right,[650] but we do not know when it became widespread. Any period from the reign of Claudius to the Flavians is possible, but there is no means of deciding for sure.

An almost complete absence of epigraphy makes it very difficult to trace the development of governmental institutions within the civitates with any confidence. A vergobret (magistrate) is mentioned on the coinage of the Lexovii, whose capital was Lisieux in Normandy, and an inscription from Saintes reads 'C. Iulius Marinus, son of C. Iulius Ricoveringus, of the Voltinian tribe, first \flameri\ of Augustus, curator of Roman citizens, quaestor, vergo[bret]' .M The early date of this inscription fits in with a graffito found at Saint-Marcel, Indre, ancient Argentomagus, which reads 'the vergobret has performed the sacrifice (vercobretos readdas)' and which dates to around a.d. 20—30. The Gallic office of vergobret may have corresponded to the post of praetor, known from Claudian Bordeaux.65 But the name of the office, whether indigenous or Romanized, is much less significant than the fact that it refers to an individual, rather than a collegiate, magistracy. The data are so rare that no firm conclusions can be drawn from them. All the same Saintes and Bordeaux were among the most urbanized states of the Three Gauls. The pride with which the powerful recalled their ancestors is also very striking. Also from Saintes was C. Iulius Rufus who proclaimed his descent from C. Iulius Otuaneunus, the son of C. Iulius Gedomo, the son of Epotsoviridus.66 The impression created by the sources, then, is that, outside the colonies, late Iron Age institutions survived under the cover of vague Roman terminology, and that the great families of the Julian aristocracy preserved their superordinate power vis-a-vis their fellow citizens.

As we have already seen, Roman citizens from the Three Gauls did not have the right, before the reign of Claudius, to stand for the magistracies in Rome. But they could gain entry to the senatorial order by imperial favour. It is surprising that only three senators are known before a.d. 70, all of them from Aquitaine. The small number of equites is also surprising: we know of only twenty or so examples in the first century a.d., from the Three Gauls and the Germanies together, only a quarter as many as are known from Narbonensis. It is as if the greatest ambition of these magnates was to be elected to the priesthood at the federal sanctuary at Condate, so winning the highest honour in the Three Gauls for themselves and their states.

It is difficult to define the exact role played by the federal sanctuary, and the ceremonies that took place there each year, beginning on 1 August, the date of the fall of Alexandria and the festival of the Genius Augusti. The events included the worship of the emperor and of Rome, competitions, and the opportunity for 'political' representation, through the medium of the concilium, the provincial assembly. All the same, the theory that Celtic traditions had been incorporated into the festival cannot be rejected out of hand. Occasional accounts of the site suggest that a sacred grove and a crowd of statues stood alongside the altar and the amphitheatre, and the organization of the concilium is also peculiar to Gaul, the chief official being a sacerdos, rather than a flamen, the other officers being a iudex, an allectus arcae Galliarum and an inquisitor Galliarum. The gathering was not an exact copy of the famous Druidical meetings mentioned by Caesar, but it may have been some sort of

« CIL xiii 590, 596-600. 46 CILxiii 1036.

ij d. gaul

transmutation of them. The place was different, as were the forms of the meeting, but important business was transacted there and it was the occasion for equals to recognize each others' paramount prestige. The creation of the Ara Ubiorum for the Germans living west of the Rhine, and of a conventus at Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges (Lugdunum Conve- narum) for Aquitanians south of Garonne, also at an early date, showed the Romans' willingness and perhaps their need, to perpetuate traditional annual festivities. Unfortunately there are too few inscriptions from either the Confluence or the Gallic states to say for certain where the sacerdotes came from, although we know that the first, elected in 12 b.C., was the Aeduan Iulius Vercondaridubnus, and that in the early first century his successors included the Cadurcan M. Lucterius Sencianus, probably a descendant of the chief Lucterus who had fought against Caesar between 5 2 and 51 B.C., and also C. Iulius Rufus from Saintes. The assembly of the Three Gauls offered Augustus a gold neck-ring, a torque, that weighed 100 pounds, and it was also the assembly, rather than the city of Lyons, who welcomed Caligula, who established a contest in Greek and Latin rhetoric there.67 The concilium demanded of the elite that they demonstrated their loyalty to the emperor and their acceptance of Latin culture and that they indulged in extravagant euergetism, but most of all it was the premier stage on which aristocrats paraded their wealth, their prestige and their rivalries. The return of a new sacerdos to his home state must have been the occasion for triumphal honours, and more than one wanted to reproduce, on a smaller scale, the entertainments he had given, and over which he had just presided.

It is necessary to return, once more, to the scarcity of inscriptions. The usual explanation given is that it represents resistance to the Latin language, although it may be more a sign of psychological difficulties surrounding the use of writing, perhaps deriving from the circumstance that in the late Iron Age the Druids had monopolized writing and it had therefore never been publicly displayed. On the other hand, Gauls made a major contribution to the Roman army. Before a.d. 68 they provided twenty-eight cavalry divisions and seventy-six cohorts, that is to say about 65 per cent of the auxiliary strength of the western provinces. Many also served as legionaries: 25 per cent of the inscriptions found in Gaul, including Narbonensis, from the reigns of Claudius and Nero, are those of legionaries. The return of substantial numbers of men who had served for years in the Roman army must have had all sorts of consequences for both the language and more generally the 'civilization' of the Three Gauls.

Assimiladon had begun, albeit slowly, not only among the elite but also among other groups lower down the social scale. The process is

5<эо

67 Sue. Calig. 20.

often described as being accompanied by extensive economic and commercial integration, but this is unlikely to have been the case. Recent numismatic studies have shown a shortage of coin that seems to have grown progressively more severe until the Flavian period. Local coinages were accepted at least until the end of the last century B.C., and after that forgeries multiplied and the countermarks designed to authorize money as official were themselves being forged under Claudius and Nero. The implications are that central government was not concerned to create an integrated monetary system, nor any real kind of economic organization. As a result laissez-faire predominated, allowing the frontier regions, where soldiers were paid in cash, to exercise a powerful attractive force, and permitting the development of profitable barter with neighbouring 'barbarians', the basis of the economy of ports like Bordeaux and perhaps Reze near Nantes, and of the great centres of distribution, above all Lyons. Apart from in some cities with special advantages, then, commerce was not a major force in creating a new mix of Gauls and Italians. The activities of the elite and the army were much more important.

Mortuary studies show that cremation was widely used, but also reveal a number of local peculiarities. Around Lyons, Briord and Roanne inhumation was none the less important, and it is virtually the only rite used in some cemeteries along the Seine between Paris and Rouen, and especially in Paris itself. By contrast, the inhumations found in the centre-west of France, in Poitou and Saintonge, are those of'high status' women, buried either in stone sarcophagi or in huge wooden coffins. These tombs are very rich in grave-goods. In the same way, the isolated tombs of the Berry, that date to the period between Augustus and Claudius, contain either inhumations or cremations but also very rich assemblages of amphorae, ceramic table services, tools, weapons and bronze objects including wine pourers, bowls, plates and simpula. The same applies to the territory of the Treviri, while in present-day Belgium, tumuli have been recorded. The aristocracy had evidently not unanimously adopted Roman customs, and alongside those nobles who had mausolea built for them at a very early date, like the example from Faverolles in the civitas of the Lingones, there were others who preferred to preserve older traditions.

I will not deal with religion here except briefly to summarize the argument I will develop at greater length in САН xi. The slender evidence we have suggests two main lines of inquiry. First, although the literary evidence tends to focus on the banning and then the suppression of Druidism, recent excavations are turning up more and more temples with concentric plans, temples of the type called fana, constructed on the sites of pre-Roman shrines. Second, Romanized religious monuments like the Boatmen's Pillar put up by the Parisii at Lutecia, juxtapose not only indigenous deities and Roman gods, but also tend to include some reference to the emperor. The epithet Augustus appears very frequently on religious inscriptions, either applied to the god, or associated with him. This is the clearest indication that the Roman emperor descended from Caesar was seen in the Three Gauls as a charismatic leader, who safeguarded peace and unity but also protected the autonomy of those peoples, even the smallest communities, who worshipped him alongside their own local gods in order to make him more truly their own.

Compared with other areas incorporated into the Roman empire, the Tres Galliae stick out like a sore thumb. The Gauls were marked out as different by their climate, by memories of ancient Gallic invasions and of Caesar's war, by their closeness to the Germans, and by their image as barbarians, possessed of great riches, but indulging in human sacrifice. Archaeology makes clear just how much rhetoric there was in Claudius' speech to the Senate, better preserved in CIL xiii 1668 than in Tacitus' rendition. Compared to Narbonensis, so quickly assimilated, the Tres Galliae seem like a world still resting on Iron Age foundations. Cities were slow to establish themselves, the aristocracies were reluctant to go beyond their territorial power bases, and the locality exercised a determining influence over all spheres of life. But the yeast was already at work. Gaul now opened onto the outside world, first the Germanies and then Britain, Gauls were serving in the Roman army, and civilization, spreading contagiously, was transforming public buildings and private houses alike. The worship of the emperor was more and more closely bound up with the power of the leaders of the state, and of its gods. Claudius, whom Suetonius called 'the Gallic emperor' predicted the future more accurately than he described the present.

CHAPTER 13e BRITAIN 43 B.C. TO A.D. 69

JOHN WACHER

I. PRE-CONQUEST PERIOD

Rome's first formal contact with Britain came with the expeditions of Iulius Caesar in 5 5 and 54 в.с.1 By then, most of the major late Iron Age migrations from Gaul to Britain had already occurred, although within Britain much political and cultural movement was still to take place. Caesar named only six tribes, among which were the Trinovantes and Cenimagni (Iceni?), with four more unnamed in Kent, and with the implication of a nameless eleventh, probably the Catuvellauni, ruled by the leader of the British opposition, Cassivellaunus. Other tribes which were to play a part in the period between Caesar and Claudius and immediately thereafter were the Brigantes, Corieltavi, Cornovii, Dum- nonii, Atrebates and Dobunni in present-day England and the Silures and Ordovices in Wales. The Atrebates arrived in Britain after the Caesarian episodes, brought over by their king Commius, who, at first an ally of Caesar, later unwisely joined the unsuccessful rebellion of Vercingetorix in Gaul; the Dobunni are usually considered to be an offshoot of the Atrebates.2 The Catuvellauni gradually emerged as the most powerful tribe in south-east England, occupying an area roughly equivalent to the kingdom of Cassivellaunus. In addition, the four tribes which inhabited Kent eventually merged to form the single tribe of the Cantiaci. Apart from the tribes mentioned by Caesar and some other literary sources, most of our knowledge of their existence and geographical positions is gained from detailed study of the coinage which they minted.3

Caesar's expeditions, even if they bore no long term success, nevertheless made Rome more aware of Britain's existence. This is partly to be seen in the greatly increased volume of trade between the island and the Roman empire, now expanded to the Channel. The trade is mentioned by Strabo4 and attested archaeologically in the numerous goods found especially on sites in the area north of the lower Thames. Politically and

1 Caes. BCall. v. 2 Allen 1961 (в 504) 75—149.

Allen 1958 (в 505) 97-508. It must be admitted, however that some modern authorities view this list of coin distributions with suspicion, e.g. Collis 1971 (в 317) 71-84.

Strab. I v.). 1-4 (199-201С)

503

Map 8. Britain as far north as the Humber.

militarily, Caesar left unfinished business in Britain, and Augustus three times, in 34, 28 and 27 b.C., planned expeditions; all were called off because of needs elsewhere. Deprived of military conquest, Augustus aimed at the maintenance of a balance of power between the major tribes, at first befriending Tincommius, son of Commius of the Atrebates, so as to balance the waxing strength of the Catuvellauni. But this diplomacy did not prevent the latter from invading and occupying the territory of the Trinovantes, an act which was contrary to the terms of the old Caesarian treaty. It appears to have been quite deliberately timed, c. a.d. 10, when Augustus was more than preoccupied with the aftermath of the Varian disaster in Germany, and it came about through the actions of a man who was to become the most powerful ruler in Britain before the Claudian invasion: Cunobelin. Suetonius gave him the title Britannorum Rex, and he was probably a direct descendant of the great Cassivellaunus.5

An alternative theory on his origin sees him, however, as a Trinovan- tian monarch who had gained ascendancy over the Catuvellauni; certainly his capital was at Camulodunum near modern Colchester, in Trinovantian territory.6 This view strains the information which we have beyond logical bounds. The Catuvellauni and not the Trinovantes were, by implication in Dio's account of the Claudian invasion,7 the prime enemy of Rome. By implication also Cunobelin had been their king. It is extremely unlikely that he would have abandoned his own tribe's name in favour of that of an enemy, whether conquered or not.

Despite the apparently anti-Roman bias of some of Cunobelin's early actions, he seems to have given a temporary stability to the tribal affairs of Britain. In Rome's eyes all was well so long as his deeds were balanced by the friendly presence, south of the Thames, of its allies the Atrebates. Unfortunately, following the death of Commius and the accession of his son, Tincommius, the kingdom was rent by fraternal squabbles, Tincommius being ousted by Eppillus, and he in turn by Verica. In each case, Augustus recognized the successful claimant, despite the appeal of Tincommius for help towards reinstatement; both Eppillus and Verica seem to have been acknowledged as client kings.

Cunobelin was not averse to allowing even more flourishing trade to grow between his kingdom and the empire, since, with its extension to the sea, he now controlled the lucrative trade routes from the Rhineland and elsewhere. His anti-Roman attitude also seems to have abated sufficiently for him to send embassies to Rome, and he may have been among the British rulers who set up offerings on the Capitol.8 But with the death of Augustus and the succession of Tiberius, he resumed in the

s Suet. Calig. 44. 6 Rodwell 1976 (e 553) 265-77. 7 Dio lx. 19-22.

8 Strab. iv.5.3 (200-1Q.

next fifteen or so years the expansion of his kingdom, adding the rest of Kent and penetrating into the middle and upper Thames valley. Pressure was also applied to the Atrebatic kingdom for the first time and it would appear that its centre at Calleva now became part of the Catuvellaunian domain. Tiberius apparently did not react to this provocation, although it is unlikely that it was carried out without protest to Rome.

Tiberius died in a.d. 37 to be succeeded by Gaius. By then Cunobelin must have been sinking into old age and he was perhaps losing his grip on tribal affairs, a factor which was aggravated by the growth to manhood of his sons. The apparent philo-Roman outlook of one of them, Adminius, may well have led to his expulsion and flight to Gaius to support his reinstatement. Gaius was then in Germany and was persuaded by Adminius that Britain could easily be conquered. Gaius assembled an army at Boulogne in a.d. 40, but a mutiny prevented it from sailing; Gaius thereupon called off the enterprise. But the expulsion of Adminius showed that all was not well among the Catuvellauni, a situation which was made worse by the death of Cunobelin and the division of the kingdom between two other sons Caratacus and Togodumnus.

Ambitious, hot-headed and possibly resentful of Roman influence in Britain, they set out on a policy of unlimited aggression which led, not only to the partial, or even total, absorption of the Dobunni, but also to the overrunning of the Atrebates, forcing their king, Verica, to flee to Rome for help, and finally to the total alienation of Rome. Verica was a client king and Roman ally, so that his expulsion could be interpreted as an insult to Rome, which, if left unavenged, would have called into question a whole area of foreign policy at a time when Rome very much relied on client rulers to maintain peace on or near the frontiers. The situation was, moreover, exacerbated by a demand for Verica's extradition and, when this was refused, by aggressive action being taken against Roman merchants in Britain and possibly even against the coast of Gaul. Verica's expulsion, therefore, served as the polidcal vindication for the direct intervention of Rome in Britain in a.d. 43.

causing many adherents to seek refuge across the Channel. There was also the question of military strategy; if Britain were not invaded, the coast of Gaul would require protection from a hostile force controlling the other side of the Channel. To protect it would mean raising the strength of the army to dangerous levels in the western mainland of the empire and no extra territory would be gained to provide its food. If the same army were placed in Britain it would be safely isolated, with fresh sources of food and other supplies. Whatever the reasons, Claudius decided to invade. A force composed of four legions and auxiliaries, altogether amounting to some 40,000 men, under the command of Aulus Plautius, until then governor of Pannonia, was assembled at Boulogne. That part of the Annals of Tacitus which included the account of the invasion is lost, and for literary evidence we have to rely on the later account of Cassius Dio,9 which is neither exhaustive nor entirely clear in its descriptions. The evidence of archaeology helps a little, but is again restricted, pointing definitely to only one landfall at Richborough.10 Yet Dio stresses that the force was divided into three sections; consequently three possibilities can be envisaged. The whole force could have landed at Richborough in three consecutive waves; but it must be admitted that the fortified beachhead there is not nearly large enough to contain so many men, while no other encampment has yet been found nearby. Secondly, it has been argued that whilst one division landed at Richborough, the other two landed at Dover and Lympne respectively; it should be noted, however, that there is no evidence at all from either site of an early Roman presence. Thirdly, it has been ingeniously argued that one division at least was directed to a landing in the neighbourhood of Chichester, in order to carry out the very necessary reinstatement of Verica as soon as possible in his kingdom.[651] The balance of probability would seem to favour the first hypothesis.

The landing was apparently unopposed. After some slight skirmishing inland, in which Togodumnus was probably killed, the first major action against the Britons was at the crossing of the river Medway, where the Roman army was victorious; it then advanced to the Thames. At this stage Caratacus is said to have fled to Wales. After a pause to allow Claudius to arrive on the scene, the advance was resumed and the emperor was able to enter the Catuvellaunian capital in triumph. There then ensued further campaigns which carried the Roman advance to a position marked roughly by a line drawn from the Humber to the Severn, where for a time it ceased. It has been claimed that it was always the intention of Rome to conquer the whole of Britain.12 If that was so, it is very difficult to explain why, having reached the line established by c.

9 See n. 7. 10 Cunliffe 1968 (e 553) 232-4. 11 Hawkes 1961 (e 545) (see n. 2) 62-7.

12 e.g. Mann 1974(0 286) 529-31.

iĵe. britain 4j b.c.-a.d. 69

a.d. 47, another twenty-three years elapsed before the major advance into Wales and the north was resumed. The army lacked neither the manpower nor the capability to advance immediately.

It seems more likely, therefore, that the original intention was only to seek a pragmatic solution to the Catuvellaunian problem by conquest and occupation; the line at which the advance stopped did just that. That it also raised a new set of military problems, which in time required their own solutions, cannot have been endrely foreseen in a.d. 43.

The limit of the advance was marked by the construction of a road, the Fosse Way, for lateral communication from Lincoln to Exeter and by the sidng of forts and fortresses along it, to the front and to the rear of it, forming a broad military zone to protect the newly conquered territory. Most of the forts were occupied by auxiliary regiments but some at least contained battle groups consisting of detachments of legiones II Augusta, XIV Gemina, and IX Hispana brigaded with cavalry. The whereabouts of the headquarters fortresses of these legions in the years immediately after the invasion is imperfectly known and still the subject of some speculation. Legio XX Valeria appears to have been left in reserve at Colchester until just before the foundation of the colonia in a.d. 49, after which it too was moved forward to the frontier.

But not all remained peaceful, even after the primary objective had been reached. Caratacus stirred up his new Welsh allies to attack the province in a.d. 47 just as Ostorius Scapula was taking over the governorship from Aulus Plautius. A campaign against Caratacus was preceded by the disarming of tribes within the new province, an act which itself caused trouble and led to a minor revolt among the allied Iceni. Once started, the campaign against the Welsh tribes was interrupted by disturbances among the northern Brigantes, whose queen Cartimandua professed a pro-Roman outlook. Indeed Caratacus, after his defeat in Wales, fled in vain to Cartimandua for protection, only to be handed over to Rome.13 There followed some years of almost continuous but confused and ill-recorded fighting in Wales and occasionally in Brigantia, the only permanent result of which was the advance of the frontier zone to the Welsh Marches, probably executed by Ostorius. Then in a.d. 60, a much more serious threat faced the province, which nearly resulted in its loss through the rebellion of Boudica, queen of the Iceni, together with the neighbouring Trinovantes.14

Much has been written about the causes of the rebellion. It is generally accepted that among them were the forcible reduction of the Iceni, following the death of the Roman client king, Prasutagus, and the refusal of Rome to recognize his queen or daughters as successors. The

Tac. Ann. xn.36; see also Hanson and Campbell 1986 (e 544) 73-90.

5<э8

Tac. Ann. xiv. 29-39.

reduction was carried out in a heavy-handed and arrogant way by the provincial procurator, Catus Decianus, which led to the flogging of Boudica and the rape of her daughters. A contributory cause was the requisitioning of Trinovantian land, including their principal religious site, for the territorium of the new colonia at Colchester; another was the probable expense of maintaining the newly introduced imperial cult. It has also been suggested that a rebellion, just at that time, was intended to act as a diversion and to distract the governor, Suetonius Paullinus, from his campaign against the headquarters of druidism on the island of Anglesey;15 if so, it failed. Be that as it may, in a.d. 60, while Suetonius was campaigning in north Wales with most of the British garrison, the rebellion exploded; Colchester, London and Verulamium were sacked and burnt, and excavations at each site have produced eloquent evidence for the fires. The small force deployed by the procurator in defence of the colonia was useless, as were the resident veterans. Legio IX, advancing against the rebels from Longthorpe, suffered many casualties and had to withdraw in disorder. Suetonius, apprised of the rebellion, hastened from Wales in advance of his main army, and reached London before the rebels, but realized that there was little that could be done to save the town. He fell back to join his advancing army and finally brought the rebels to battle, probably somewhere along the middle section of Wading Street. The rebels were routed and the province saved. The resulting punitive campaign in East Anglia, together with the battle casualties, must have seriously impoverished the Iceni and Trinovantes for at least a generation, leading to a much slower rate of Romanization in later years.

In the ensuing decade, attempts were made to restore the province. A new and more enlightened procurator, Iulius Classicianus, replaced Catus Decianus, who had fled to Gaul at the outbreak of the revolt, while a succession of milder governors ended hostilities and helped to placate the natives. So successful were these measures that the province was deemed sufficiently safe for legio XIV to be withdrawn in 66. Unfortunately, the peace was shattered by the Roman army itself, disillusioned with the resulting period of inactivity. A mutiny led by a legionary commander, Roscius Coelius, forced the governor, Trebellius Maximus, to flee the province in 69. But by then affairs of greater moment gripped the whole empire. Nero had committed suicide in 68 and the power struggle which ensued left its mark on Britain. Its new governor, Vettius Bolanus, was a supporter of Vitellius, who was eventually defeated by Vespasian. Moreover, legio XIV which had supported Otho also returned to Britain for a short time, while the remaining legions had supported Vitellius. Vespasian therefore inherited a province of doubt-

15 Webster 1978 (e 564).

5 io 13«. britain 43 в. е.—a.d. 69

fill loyalty and it was not until the early 70s that he was able to take remedial action.

iii. organization of the province

Once the midland frontier zone had been created, much of the south east seems to have been demilitarized, and by a.d. 49, with the dispatch of legio XX from Colchester to Gloucester, the way was open for the development of the newly constituted province. It embraced two client kingdoms: the resurrected sometime kingdom of Verica, now renamed as the civitas of the Regni, with a new king, Cogidubnus, in west Sussex and Hampshire, and the Iceni in East Anglia.[652] These two kingdoms enabled Rome to make economies in manpower, although they were very different in character and dependability. According to Tacitus, Cogidubnus proved a staunch ally to Rome and led his kingdom steadily towards peaceful Romanization until his death, probably in the Flavian period.[653] Indeed for a short time during the Year of the Four Emperors (a.d. 69) he may have helped to hold the province against a mutinous army and an unreliable governor on behalf of Vespasian. The idea that he was given the status of an imperial legate has now been undermined by a re-reading of the damaged inscription from Chichester[654] which records his name and titles. Certainly, whether legate or not, something significant was happening in his kingdom at that time, for some of what are probably the earliest urban defences in Britain are to be found there. The Iceni appear to have been less ready to accept the benefits of the conquest, and, on being forcibly disarmed by Ostorius Scapula, staged a minor revolt, which was quickly put down; but it was a presage of more serious things to come.

In the remaining area of the south east, through which the Roman army had passed rapidly, it is possible to detect the establishment of three civitates-. units of local administration, formed from the Iron Age tribal territories embraced by the Cantiaci, the Catuvellauni and the Trinovantes.19 The latter first appear in history in Caesar's account of Britain, in a somewhat paradoxical way. Although he refers to them as the most powerful tribe in Britain, they are at the same time also depicted as seeking his protection and assistance to repel attacks by their western neighbour, the tribe of Cassivellaunus. There is no further mention of them, not even at the conquest, until they again appear, embroiled in the Boudican rebellion; consequently, it must be assumed that they had re- emerged under Rome as an independent unit of local government after years of Catuvellaunian domination. But it was their territory that was chosen by the Roman administration for the foundation of the first city in Britain, to act as an example of urbanization to the inhabitants of the new province: an act that was to have far-reaching consequences.

iv. urbanization and communications

The foundation of the colonia at Colchester, on the site of the recently evacuated legionary fortress, in a.d. 49, is mentioned by Tacitus as a deliberate act of policy, whereby a reserve of legionary veterans was maintained in the south east in the absence of any worthwhile regular garrison.20 It was also intended to act as a model of urbanization for the native Britons, and incolae — native inhabitants — were included in the population from the first. The earliest houses of the veterans have been shown by excavations to owe much to the legionary structures that had preceded them, although there were significant changes in layout; yet some of the streets of the fortress were perpetuated.21 The position of the forum is still not known with certainty although several sites have been proposed; Tacitus mentions a curia. He also refers to a theatre which has now been identified by excavation, but he stresses that there were no fortifications at the time of the Boudican rebellion, which implies that the legionary defences had been dismantled.22 Astride the main road to London on the western boundary, a triumphal arch was constructed, presumably to commemorate the foundation of the colonia and to honour its founder, Claudius. His memory, though, was more than adequately recognized in the construction of the principal building connected with the new city. This was the great temple of Claudius, which was also to be the centre of the imperial cult in Britain.23 All that remains now is the podium, lying beneath the Norman casde; originally, it stood within a great colonnaded courtyard with an entrance to the south. It is often argued that Colchester was also intended to be the provincial administrative capital, a function that was later to fall on London. It should be stressed, however, that there is no evidence to support this suggestion, and in the extremely fluid state of the new province, it is more likely that the 'capital' would tend to be where the governor was; there is nothing to link him specifically with Colchester.

Some other urban centres had their beginnings in the years immediately after the invasion. Canterbury, a recognized Iron Age site, early became the capital of the civitas Cantiacorum, although many of the features originally attributed to its foundation are now thought to be somewhat later, and the main development did not occur until the turn

20 Tac. Ann. xii.32. 21 Crummy 1982 (e 332) 125-34. 22 Tac. Ann. xiv.32.

23 Sen. Apocol. 8.3; see also Fishwick 1972 (e 534) 164-81.

512

ije. britain 43 b.c.-a.d. 69

of the first and second centuries. But the final street plan may owe some of its irregularities to the lines of earlier streets and existing buildings.[655]London was recognized by Tacitus as a flourishing trading centre even before the Boudican rebellion;[656] houses and shops of the first town, burnt in the rebellion, have been uncovered over a wide area, but litde is known of any public buildings. There are indications of an embryonic street system in the area north of the Thames bridge, the possible northern abutment of which has been identified in excavations in Pudding Lane.[657] There is also evidence to show that at least some provincial administrative functions were centred on London, possibly even before the Boudican rebellion, and certainly after it. The procurator, Iulius Classicianus, died in office and was buried at London; his ornate, altar-style tombstone was found reused in the later town wall on Tower Hill.[658]

Verulamium, like Canterbury, was also founded on the site of a major Iron Age centre, the probable sometime oppidum of Tasciovanus. It almost certainly served as the administrative centre for the Catuvellauni from its beginning. Arguments, however, still continue over whether, and if so when, municipal status was conferred. The most recent view holds that it was granted under Claudius and at about the same time as the foundation of colonial Colchester.[659] But the evidence is not decisive and relies to a large extent on the interpretation of a passage of Tacitus.29 Excavations have identified a rudimentary street system of Claudian date, and a number of buildings, mostly, as at both London and Colchester, constructed with timber frames and wattle-and-daub walls, and so consumed in the Boudican fire. One block in Insula XIV has been identified as a range of shops, possibly built as a speculative venture by a Catuvellaunian noble and rented out to his retainers or managed by slaves.30 The forum and basilica are dated by the dedicatory inscription to a.d. 79,31 although earlier structures may still lie undiscovered beneath them. Thefown was encompassed, probably in the Claudian period, by a bank and a ditch; when the town later expanded beyond them this line was commemorated by two triumphal arches set astride the London- Chester road.32

Two other embryonic urban settlements may be considered as belonging to this period and both lie within the likely kingdom of Cogidubnus. The site of the town at Chichester, in the kingdom's heartlands, had an early military presence, but it is not known preciselyhow long it lasted. Yet, alongside the military base, or after it, there is evidence for a major public building dedicated during Nero's Principate.33 Probably slightly later, the Cogidubnus inscription34 displays advancing Romanization, not only in the existence of a temple to the purely classical cult of Neptune and Minerva, but also to social organization in the collegium fabrorum, or guild of craftsmen. Also, very likely situated in Cogidubnus' kingdom, the Iron Age oppidum at Silchester has produced elements of early urbanized development which included a bathhouse and amphitheatre35 of Neronian date, and a slightly later, but still Neronian, timber building on the site of the laterforum and basilica-36 This building has been variously interpreted as a market square, a residence for Cogidubnus or military principia. But the two phases of fortification on different alignments which were thought to belong in the same context, have now been shown to be of pre-Roman origin.37

Communications rapidly came to play a crucial part in the development of the new province. Roads, such as Watling Street, Ermine Street, Stane Street and the Fosse Way, were primarily constructed for military reasons, but, once in existence, would have been used by all.38 They linked a series of burgeoning ports such as Richborough, Dover, Fishbourne, Colchester and London, which provided havens for the increasing number of merchants wishing to exploit the new markets. No doubt the major rivers were likewise pressed into service; it is worth noting that water transport was much cheaper.39 It should also be remembered that the main roads, even with their straight alignments, metalled surfaces and good drainage, probably degenerated into a series of muddy potholes in winter, possibly making road transport in Britain, apart from pedestrians and pack animals, a seasonal affair which was confined mainly to the summer. The upkeep of the road system, together with its ancillary structures such as bridges, devolved upon the local magistrates of the town or civitas through whose area they passed.

514 I 3 BRITAIN 43 B.C.—A.D. 69

Verulamium, Colchester and London, and in the kingdom of Cogidubnus. It has, indeed, been claimed that in these rural areas the pace of Romanization outstripped that in the new towns, with better quality housing appearing in the countryside at an earlier date.40 It may be, though, that these first ventures into Romanized country life were not the work of native Britons, but of migrants from Gaul or further afield, eager to invest in the new province. Such villas as Eccles (Kent), or Angmering (Sussex), both probably of late Neronian or early Flavian date, would seem to fit best into this category, but the early foundation at Rivenhall (Essex) is held to have been built by a rich native landowner.41 The stimulus given by the Roman occupation to increased agricultural production was at first twofold: the demands of the tax-collector and the food requirements of the army. Whenever or wherever troops have been stationed in foreign or occupied territory, they have always created a demand and have become a source of accessible wealth for the local populations; the Roman army in Britain was no different. It is unlikely that British farmers could have immediately supplied all the food needed by the army. Total requisition would probably not have been a workable policy for an army of permanent occupation, since it would have left the producers to starve. Nevertheless, it must be reckoned that, within a reasonable time, production would have been stimulated sufficiently to meet most needs. This could only have been done by increasing the areas of arable land, the clearance of which would have helped in supplying the sudden demand for the huge quantities of timber required for constructing the many new military and urban buildings. Once production had begun to expand, it must have occurred to many British farmers that there were profits to be made by increasing it still further, in order to supply other markets offered by the new towns. This, or something like it, will have been the economic base on which, in time, the villa system grew.

in southern Gaul, and other fine wares from places like Lyons;[660] mortaria, kitchen mixing bowls, also came in quantity. At first, Bridsh potteries only supplied coarse wares, many sdll of Iron Age, wheel-made, traditional types. Gradually, however, new forms began to infiltrate, and within a decade or two, several centres were in full production, supplying both military and civilian markets. Other imports included glassware from the eastern Mediterranean and metalwork from Gaul and Italy. But Britain slowly built up its own industries, which, apart from the manufacture of pottery, were usually situated in the towns. A bronze-smith's workshop existed at Verulamium before the Boudican rebellion, where goods would have been both manufactured and sold on the premises.[661] Unfortunately, the evidence for industries and trade connected with organic materials such as wood, leather or cloth, does not often survive. But there is evidence for the exploitation and export of minerals such as Wealden iron and more notably the lead/silver ores in the Mendips worked possibly as early as a.d. 49 by a detachment of legio II.[662] It is interesting that the pattern of trade between Britain and other parts of the empire in some ways resembled that of modern trade between developed and undeveloped countries, the former exporting manufactured goods and the latter raw materials. Strabo listed corn, cattle, hides, slaves, gold, silver, iron and hunting dogs as British exports in the time of Augustus; ivory ornaments, amber, glass and other manufactured trinkets came in return, although wine and oil might well be added to the list.45

vii. religion

The new province was already well served by its native cults, which tended to be localized; yet there is evidence from the Roman period for the existence of tribal deities, such as Brigantia,46 and for sites which had more far-reaching significance, such as Bath with its deity, Sulis, presiding over the hot springs.47 In most instances, Celt and Roman possessed a common basic level of superstition.48 Consequently, the introduction of classical cults would have struck an immediate response; Celtic and Roman deities often shared similar areas of supernatural influence, so that Minerva could be identified both with Sulis at Bath and Brigantia in the north. But totally foreign to British religious practice was the introduction of the imperial cult, with its physical centre at Colchester. This provided a common element in the empire which had

13«. BRITAIN 43 B.C.—A.D. 69

an enormous diversity of religious practice and at the same time incorporated expressions of loyalty to the imperial household. It required an expensive commitment on the part of the leading inhabitants of the province - the size and magnificence of the temple of Claudius attracted unfavourable comment even in Rome. Yet the concept had worked well in Gaul, with its great centre at Lyons, and there was no reason to believe that it would not work in Britain; that it was to become one of the causes and focal points of the Boudican rebellion could not have been foreseen.

5i6

The account given above suggests that the process usually described as Romanization in Britain was very uneven in place, time and depth. Although the Romans encouraged aemulatio in their provinces and often provided models of behaviour or structure, little pressure was applied to force the change. The rate, therefore, at which any individual or community adopted the new ways was largely a matter of personal inclination. Provided that existing ways of life and behaviour were acceptable to the Roman administration, and taxes were paid, no change was demanded. Naturally, therefore, the fastest rate of Romanization is to be detected in those areas of Britain which had been affected by the most recent migrations from Gaul, whose people had already been in closer contact with Roman culture. Practical, less often financial, help might be provided for Romanizing communities, as in the founding of new towns; but in the end, the main burden of the cost had to be paid by those same communities or its individual members. This, in itself, imposed the limit to the progress of Romanization. Strictly, the Roman civil administration was not concerned with the welfare of society, except insofar as a well-ordered province made tax collection easier. Nor could it do much more to help, even given the best of intentions. It was probably no more than a few hundred strong, consisting mainly of military personnel seconded for these duties, and simply did not have the manpower to influence every individual member of the estimated 2 to 3 million population of the province. Consequently, it could only function properly through delegation of responsibilities to the native people; the degree of delegation could vary greatly from place to place depending on the natives' fitness to accept it. Hence, also, the towns, villas and other structures of Roman Britain ultimately exhibit many variations in size, planning and degree of sophistication, mainly conditioned by the presence or absence of financial restraints, or will.

CHAPTER 13/ GERMANY

С. RŬGER

I. INTRODUCTION

After 50 B.C. when Caesar left Gaul, Gaul's eastern and northern border lay on the Rhine.1 The aim of securing the Roman north west against migratory movements and wild attacks from north and east by means of a border line that could be precisely marked out was achieved. In the upper Danube region of central Europe, to be sure, the policy was limited to gaining control over the alpine passes through which for almost 300 years uncontrollable attacks on Rome's alpine approaches, indeed attacks on the city itself, had been launched.

Caesar's conquest of Gaul had an effect on the migratory movements which had obviously been taking place for centuries in the north-west part of the European continent. Caesar would not countenance the continued crossing to the left bank of the Rhine by Germans. But Germani Cisrhenani were already present on the left bank of the river. According to Caesar's own definition the latter included the Eburones in the area between the Rhine and Maas and the Caerosi, Paemani, Segni and Condrusi who inhabited the Eifel and the Ardennes. But the epithet Germani might never have meant more to him than 'stern warriors'. Geographically one must include the Texuandri to the west of the Dutch and Belgian river Maas. Although the amount of Celtic in their languages seems easier to isolate and define than the Germanic, which was still at its earliest stage of development, we can identify some characteristics of primitive Germanic character, like the doubling of

1 The main literary sources for Germany in this period are Cassius Dio (Books liv-lvi), Velleius Paterculus (11, 60-132) and Tacitus (Ann. 11, xi.16—19, xn.27—8, xin.55-6; Hist. iv.12-37, 54-79, v.14—26 (Civilis and the Batavian Revolt)), Strab. iv.3ff (i9ocff) and 289-329c Book vn). Tacitus' Geraania, although written at the end of the first century a.d., contains a great deal of relevant and important information. The literary sources are collected by Capclle 1957 (e 572) and Klinghoffer 1955 (e 582). The inscriptions are collected in CIL xiii; for later additions see R. Finke, BRGK 17 (1927) 31-105,201-14; H. Nesseihauf,ibid. 27(1937), 66-13, H. Lieb, H. Nesselhauf,ibid., 40(1959) 129-216, U. Schillinger-Hafele, ibid. 58 (1977) 473-561. For coins see the volumes of Die FundntSn^en der romiseben Zeit in Deutscbiand. There is a huge amount of archaeological evidence, much of which may be found in the periodicals Germania, Bonner ĵabrbŭcber and BRGK. There are useful surveys by Schonberger 1969 (e 591) and Raepsaet-Charlier 1975 (e 587). See also ch. 13d, no. i.

517

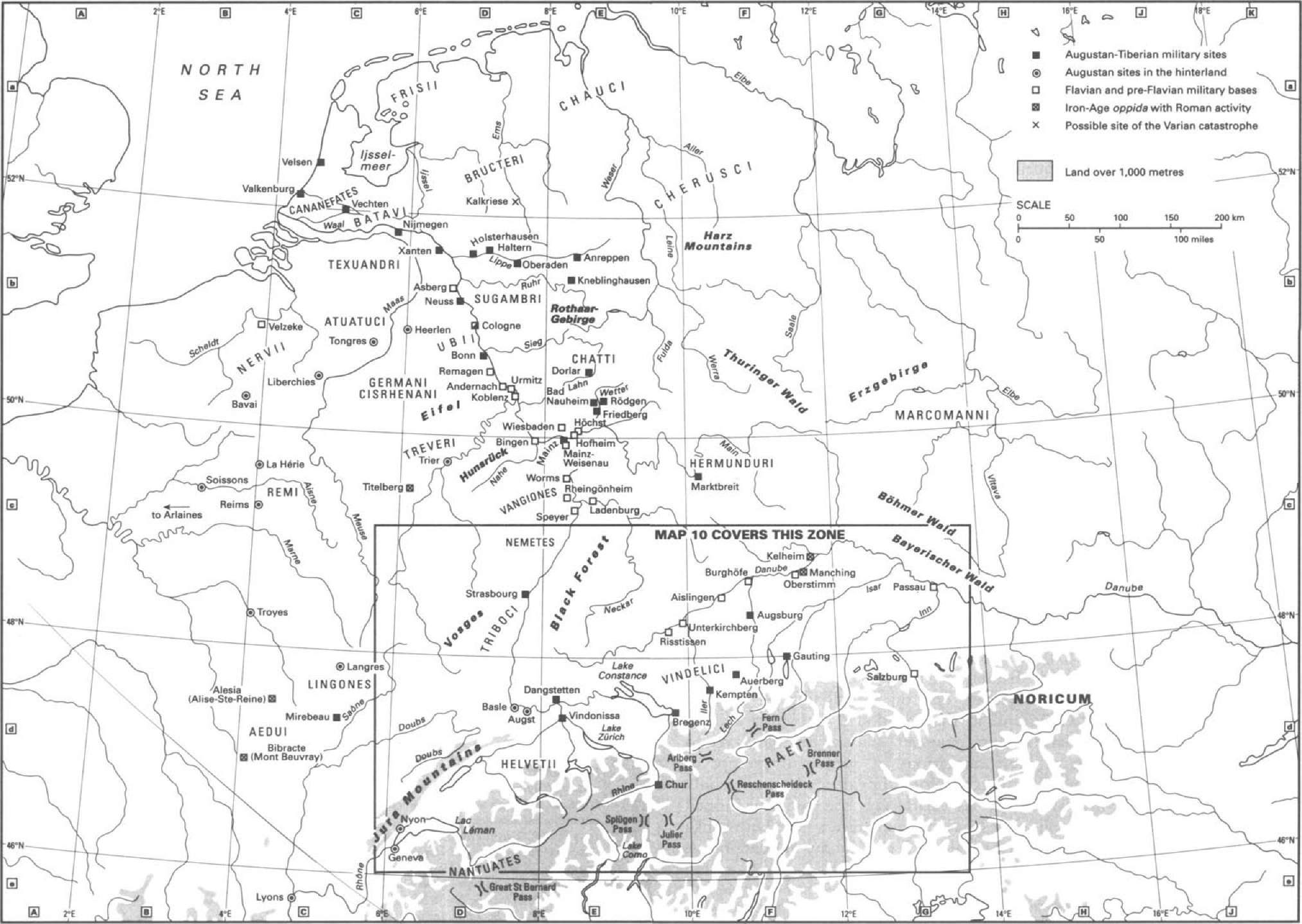

Map 9. Germany,

certain consonants or throaty pronunciations unknown to the Celtic speaker.2

To north and west these tribes were hemmed in by Belgic tribes who had, according to Caesar, a Gallic character - the Menapii, the Nervii, the Remi and Treveri. The last-named made considerable play of their Germanic origin, according to Tacitus, something which is difficult to reconcile with the 'Germani qui trans Rhenum incolunt' involved in Caesar's Helvetian affair.3 Linguistics and archaeology have brought to light little or nothing Germanic in the territory of the Treveri, or in the territory which later became the Agri Decumates - nothing at least that can be measured against the culture of the Weser and Elbe Germans as revealed by archaeology, or by the findings of Celticists in the fields of genetic affiliation and linguistic geography. Were the Treveri involved perhaps in the 'Germanic' tribal thrust into the heart of Gaul after 113 B.C., or that of 109 which brought defeat to the ex-consul, Marcus Iunius Silanus, or were they among those who eventually settled in the heart of Gaul after 115?4

How ancient can tribal traditions be? What was the Germanic element that made the Tacitean Treveri allegedly so proud of their origins? It is to be found according to linguists and archaeologists as sparsely in the Moselle area as on the right bank of the Rhine in south-west Germany, where language survivals from the pre-Germanic occupation (i.e. in the period before the Alamannic raids of a.d. 233) show next to no Germanic traits. That is also true of the Nemetes, Triboci and Vangiones who moved under Caesar or in the post-Caesarian period to settle on the left bank of the Rhine. Nervii, Menapii, Eburones and Treveri mark the northern edge of the oppidum-based civitates of the second and first centuries B.C. (LaTĉneCtoLa Tĉne Di). This is always viewed as Celtic. By contrast the north was populated by tribes who in the post-Caesarian disposition belonged to the area south and west of the Rhine as far as the North Sea: Cananefates, Batavi, Suebi (Sugambri/Ciberni), Ubii, Nemetes, Triboci and Vangiones, and on the right bank Tacitus' 'levissimus quisque Gallorum' in the abandoned Helvetian area of south-west Germany, later the agri Decumates.5 It is not possible, as yet, to establish the pattern of these migrations. A successful attempt to reconcile literary sources with archaeological evidence has so far only been made in the field of coinage. As Tacitus says, the Batavians formed part of the large tribal unit of the Chatti whose centre was on both banks of the river Lahn in the Westerwald and the Taunus mountains. A

The names of soldiers (such as Chrauttius) at Vindolanda, garrisoned by Tungrian and Batavian units at the end of the first century a.d., appear to be the earliest evidence of this kind, see A.K. Bowman, J.D. Thomas, J.N. Adams, Britannia 21 (1990) 33-52; Weisgerber 1968 (e 599) 143-68.

Tac. Germ xxviii, Caes. BGall. 1.22-9, CSP- z'-4- 4 Livy. Epit. 63, App. BCiv. 1.29.

5 Tac. Germ, xxix.4.

Chattan dependency has proven to be obvious for the Batavian coinage in La Тёпе D2.[663] We can say nothing, however, about other material remnants of a migration which occurred a generation after Caesar, although one might expect these people to have had the ability and experience to produce pottery and to have brought with them the techniques of production which would leave their mark, for at least a generation or two, in the type of ware and the shapes of the vessels.

The setdement of these tribes in the north west of Caesar's Gaul took place with or without Rome's approval and supervision. The literary sources for the period between Caesar's departure and the arrival of troops on the Rhine under Augustus (16 в.с.) make repeated comments, particularly with reference to the time between M. Agrippa's two periods of activity in this region (39/8 and 19/18 b.C.), which lead to the conclusion that there was a deliberate policy of settling right-bank Germans on the left bank of the Rhine. And many a commander on the Rhine claimed prestige at Rome for a victory 'de Germanis' or for outstanding feats of military engineering such as the digging of canals or the re-routing of waterways. Of course the post-Caesarian forces in Gaul were distributed according to plans which were in no way directed to give them a function protective of the Rhine zone, as is shown by both the literary and the archaeological evidence for the deployment of winter garrisons throughout the interior of Gaul. Tiberius and Claudius provided for that for the first time between a.d. 17 and 47. Moreover, a miserable defeat, like that of the general Lollius in 17/16 в.с. ('maioris infamiae quam detrimenti', 'involving more ignominy than actual damage'),[664] demonstrated the tactical deployment of the post-Caesarian army as a striking force. That left the Germans on the right bank enough time to settle down, even without Rome's blessing, in the devastated land formerly belonging to the Eburones and the Menapii who had been pushed to the Channel coast.

The north-west European lowlands reveal that cultural movements spread from south to north, doubtless for the whole of post-Neolithic prehistory and particularly during the Hallstatt and La Тёпе periods (800-50 B.C.). The most northerly evidence for large-scale tribal organization and aristocratic tradition can be traced in Treveran territory. The war coalition of the Eburones fell apart again immediately after their defeat by Caesar. The name of the Eburones is no longer found in the Roman period. Their heartland on both sides of the Maas is for the well- informed elder Pliny a diffuse tribal area, 'pluribus nominibus'.[665] The impoverished isolation of the north, which until the third century в.с.

enjoyed an 'epilithic culture', using old-fashioned stone topis and implements, can only be explained in terms of lack of local metal resources and the lack of economic opportunities for obtaining metal by exchange. It was very difficult in the first millennium в.с. for the new technology to gain a foothold in the poor diluvial geology of north-west Europe. In the rich south of the area, as in central Gaul, we come across names of local aristocrats whom we can recognize as the clientelae of those families who in the second and first centuries B.C. played a part in Roman campaigning in Gaul: Domitii, Cornelii, Valerii, Vibii, Calpurnii. In this Romanized clientela we often find the title amicus populi Romani.

In the north such pre-Caesarian involvement with Rome as an important instrument of Romanization is missing. There are no lowland finds of early first-century amphorae of type Dressel ia in the continental north west.9 Diplomatic contact with the German king Ariovistus went as far as the exchange of exotic royal gifts in hellenistic style.10 Caesar did not change the system, but with frontier security in mind emphasized the difference between cis- and trans-rhenane people. Here there arises a curious dichotomy between archaeology and linguistics on the one hand and ancient (and also modern) historiography on the other. To judge by the canons of typology and language the north—south divide follows an east—west line north of the Eifel and Ardennes, while historians place it east and west of a north-south line along the Rhine. This division takes the form of a cross - it is, quite literally, a crux. All the models advanced to account for the popular groupings and process of ethnogenesis in the north-west quarter of this crucial field, such as the idea of an independent north-west block that differs from the Germanic and Celtic and represents a genuine third force, have so far proved unsatisfactory, despite all the efforts of historians and archaeologists.

The establishment of Roman rule in north Gaul can be seen archaeolo- gically at central places like the great Treveran oppidum of the Titelberg in Luxembourg. Here we have names of money-coining Treveran chieftains who are dated by the numismatists to between the arrival of Caesar in Gaul and the crushing of a Treveran revolt in 29 в.с. They produced the so-called second Treveran group of coins (the first belongs to pre-Caesarian times).11 Vocarant[ ] and Lucotius appear as pre- Caesarian chieftains' names, while Pottina and Arda occur under Caesar. None of these personalities crop up in Caesarian literary records. There seem to be no later coin legends belonging to Treveran chieftains. Then there appear the issues of Aulus Hirtius, probably of 45 B.C. In this year, in which he became pro-praetor of Gaul and received the tide imperator, his minting perhaps reflects the triumphal elephant-ride of Cn. Domitius

9 Roymans 1987 (e 588). 10 Caes. BGall. 1.44, Pliny, HN 11.170.

11 See Heinen 1985 (e 580) 27-50.

Ahenobarbus (cos. 122 b.C.), after his victory over the Allobroges in 121 b.C., which saw the end of tacdcal deployment of elephants on the European continent. The final type in the Treveran coin series was issued by the freedman Germanus, mint-master of an aristocrat Indutil- lus in about 10 b.C., and thereafter it was perhaps minted in the new Treveran capital of Augusta Treverorum.12 Interestingly, a Roman garrison was posted on the Titelberg from 29 B.C. until the Augustan offensive of 16 B.C., without causing the abandonment of the surrounding oppidum. This garrison must have needed the large quandty of small change which was found there and which had to a large extent been minted there, too. For the first dme now, Roman imported goods appear in the north west of continental Europe.The merchants who followed Caesar's army must have left behind Mediterranean amphora types and Campanian ware along with types of this period. So far they have been found neither on the Rhine nor in the whole region attributed to the northern tribes. The few Campanian-style black sherds and the wine and garum amphorae were found at hill-sites belonging to the ppst-Caesarian period. That sets the north-western area of Gaul clearly apart from the south. Here exports from the coast of Campania have left their traces on the Ligurian coast and the Cote d'Azur, then up the Rhone and Saone and so on to the Rhine bend, where typically the goods are not carried down the Rhine, but north-eastwards right across the later Raetia to the Danube. It seems that there was a trade route in wine from the Mediterranean before the great upheavals in our area which took place between La Тепе В and La Тепе С in the Eifel-Ardennes region. These upheavals may perhaps lie behind the tribal tradition of the Treveri about their Germanic origin. Be that as it may, these Mediterranean imports have nothing to do with Romanization. The few black sherds of Campanian ware and the wine and garum amphorae of the north west turn up at places which must be the result of post-Caesarian military logistics and associated trade, such as we see on the Titelberg in Luxembourg and perhaps on the Petrisberg at Trier.

A number of other matters bear on the question of Romanization. It is useful and valid to adduce Roman nomenclature in the north west as an indicator of Romanization. It can be emphasized that we know many Iulii, Tiberii and Claudii in our area of interest. The list of the north-west Gallic nobility from the Ubii, Treveri, Batavi and Cananefates caught up in the revolt of a.d. 69/70 is full of these names. Their families will scarcely all have received Roman citizenship in Caesar's time - perhaps not even the majority did so. It seems that the Romanization of Gaul after the second triumvirate will have followed the same course as it did in the East, where clientelae were formed in the triumviral period through

12 See Heinen 1985 (e 580) 19-30, 58-9.

the Aemilii and Antonii. Obviously in Octavian's territory and during the interregnum the same process took place in the name of the Iulii as a reaction to his adoption. One must not underestimate the vivid memory of Caesar expressed in myths about him in eastern Gaul and the Rhineland. The temple of Mars at Cologne for example possessed a sword of Caesar's, a precious relic steeped in omens:13 in the frontier lands of eastern Gaul there was a noble whose pedigree reflected descent from a liaison of Iulius Caesar with his maternal ancestor.14 As early as the time of Agrippa's presence and under the later governors of both Germanies, bridge building over the Rhine — and much else besides — must have had its origins, at least to some extent, in emulation of Caesar (aemulatto Caesaris). The tendency of modern historiography to assign fixed dates to everything, and to offer other explanations for the Rhine bridges should not obscure the fact that Iulius Caesar's image was still a living force on the Rhine throughout the first century a.d.

Agrippa, the most intelligent and promising of Augustus' generals, did not see himself in a leading role. Both his periods of activity in this region, that of 39/38 B.C. and that of 19/18 B.C., served less to give him a high profile in Gaul than to reinforce the posidon of Octavian/ Augustus. The most important date for the establishment of the ideology of the new Caesar was the erecdon at Lugdunum of the Pan- Gallic altar, the Ara Galliarum, traditionally dated to 12 B.C., the year of Agrippa's death.15 There followed, probably in the first decade a.d. the foundation of an Ara Ubiorum along the same lines as the ideological centre of the cult of Rome which had already been provided for the Gauls at the confluence of the Saĉne with the Rhone at Lyons. But the Ara Ubiorum was not brought into being until a firm basis had been laid for the occupation of the land between the Rhine and the Elbe, a development designed to protect Gaul and to create a new province north of the Alps which bordered Caesar's old conquests.