1 See САН ix2, ch. 1The evidence for provincial administration under Augustus and the Julio- Claudians is mainly inscriptional, supplemented by scattered references in the literary sources. No attempt is here made to provide exhaustive documentation. Care is needed in using the more abundant documentary and literary sources for the period from the Flavians to the Severi which are likely to reflect a more highly developed provincial administration than that which existed between 4j b.c. and a.d. 69. Some later items of evidence are cited in what follows, but only those which seem unlikely to be seriously anachronistic.

344

economic scale, then negotiators, veteran colonists and increasing numbers of assimilated provincial Roman citizens. For all this the visible and effective support system lay in the military establishment, the institutions of provincial and civic government, the power of Rome's currency, the increasing dominance of her economic interests, and the gradual spread of Roman law.[503]

The patterns of provincial government established in the late Republic certainly survived the triumviral period, although it is difficult to see whether the political and military disturbances entailed any long- term disruption on more than a local scale. From the point of view of Roman magistrates and officers serving in the provinces, the arrangements enunciated in the Lex Titia of 27 November 43 в.с. and emended after Philippi offered the triumvirs the opportunity to exercise patronage and appoint supporters to provincial governorships and legateships; the more general implication was the evoludon of 'spheres of influence' which gave them access to the military and financial resources provided by the provinces in their areas.[504] But it would be mistaken to deduce from this that either the constitutional power or the influence of a triumvir was limited by any 'iron curtain'. Antony might write to the koinon of Asia on the subject of privileges enjoyed by athletes and artists, but Octavian was also able to maintain his close relationship with Aphrodis- ias-Plarasa in Caria, to bestow personal privileges on the naval captain (nauarchos) Seleucus of Rhosus and to issue an edict on veteran privileges whose beneficiaries were not confined to one part of the empire.4 But the solicitude of a triumvir for Rome's subjects was not universal even in his own area; some communities suffered from neglect or from inability to enlist effective aid and support, as is suggested by the evidence for internal faction and belated reparation for damage caused in the Asian cities of Aphrodisias and Mylasa during the invasion by Labienus and the Parthians.[505]

The enduring administrative arrangements made at the beginning of 27 B.C. will certainly have owed something to the experience of the previous fifteen years, even though it was politic to suppress any overt appeal to triumviral precedents. The assignation to Augustus of a large provincia, with leave to govern it through senatorial legates appointed for terms determined by the princeps, might rather have recalled the Spanish governorship of Pompey the Great in 5 5 B.C. As defined in the first instance, Augustus' province was to include Spain (though Baetica was soon removed), Gaul, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus and Egypt (governed, since 30 B.C. by an equestrian praefectus personally appointed by the princeps).[506]Within a few years Cyprus and Narbonensis were to be returned to the control of proconsuls, selected by the traditional lot for annual governorships and by the end of Augustus' reign Illyricum, now reorganized to form the provinces of Pannonia and Dalmatia, was in the emperor's hands.[507]

New provinces, by their very nature, demanded assignation to the emperor. Distinctions of rank existed within the categories of governors of 'imperial' and 'public' provinces, the major military imperial provinces being entrusted to men of consular status, the lesser to praetorians, the Senate appointing ex-consuls only to Africa and Asia, ex- praetors to the remainder. For those imperial provinces normally entrusted to equites, the prefecture of Egypt was perhaps the prototype; others were governed by men whose positions evolved from military praejecturae or civil procuratorships, becoming assimilated under the general title of procurator in the reign of Claudius. These governorships were in no constitutional sense reserved for men of equestrian rank - a freedman could be appointed deputy-prefect of Egypt and there is no evidence that Pallas' brother, Antonius Felix, was elevated to equestrian rank to hold the prefecture of Judaea.[508]

It is essential to emphasize that under Augustus and his successors practice remained flexible. It allowed provinces to be governed in groups, a province to be transferred from the control of a proconsul to that of a senatorial legatus Augusti or an equestrian governor (or, occasionally, vice versa), to place public and imperial provinces under a combined governorship, to allow a province to be 'upgraded' from equestrian control to that of a legate or from a praetorian to a consular legate, to recognize, in adjacent provinces, although perhaps only in special circumstances, the superior status of the legatus Augusti of the one to the equestrian praefectus of the other.[509] There are obvious differences between the categories of governors in length of tenure and method of appointment. Legates and procurators, appointed directly by the princeps, normally enjoyed a tenure of several years; proconsuls were appointed by lot and served for one year, although there are isolated examples of prolongation and of appointment without the lot (extra sortem). Beyond that, powers and responsibilities tended to become increasingly assimilated (this had been the purpose and effect of the law regularizing the position of the equestrian prefect of Egypt10) and proconsular independence of the emperor is all too easily exaggerated.

The evolution of this 'system' shows that the implications were far- reaching, although not in any sense which imposes a misleading division of the empire into two halves or two separate methods of government. Augustus could have claimed, if he were ever asked, to be entitled to act in his own and in the public provinces in virtue of his consular imperium until 23 B.C.; a consular decree of Augustus and Agrippa was certainly applicable in the province of Asia not long after 27 в.с. Thereafter he might claim to act by virtue of the lifetime grant of imperium proconsulare maius. But the renewal of the grant of theprovincia in 18 в.с. (and at five- and ten-year intervals thereafter until the practice lapsed after a.d. 14) seems to show that at first the imperium was in principle separable from the territories assigned to him.11 That these were all regarded, at least in the beginning, as provinces of the senatus populusque Komanus seems evident if we accept Velleius' implication that Egypt's tribute was properly the revenue of the aerarium, Tiberius' censure of his legates for not sending reports on their provinces to the Senate, or the fact that the operation of the emperor's Special Account (Idios Logos) in Egypt could be affected by regulations made by the Senate.12 On the other hand, there is abundant evidence to show that, in fact, business from both public and imperial provinces tended to gravitate towards the emperor as the most clearly identifiable and effective source of power. The first of Augustus' Cyrene edicts can just as naturally be taken to show this as any implied exercise of imperium maius, since it clearly shows the Cyreneans taking the initiative by consulting the princeps, and it is noteworthy that Tiberius, by contrast, thought it appropriate in similar circumstances not to handle the business himself or in conjunction with the Senate, but to allow the Senate an illusion of its traditional functions (imaginem antiquitatis) by remitting to it embassies from cities in proconsular provinces.13

governed by procurators, then transferred to legates in the second century; for the relationship between the prefect of Judaea and the legate of Syria see Joseph., A] xvni.88-9, xx.132, BJ 11.244 and Schŭrer 1973 (e i 207) 1. 360-1. For the status of the provinces in a.d. 69 see Table 2.

Extended tenure of legateships: Tac. Ann.1.80; proconsul appointed extra sortem-. GCN 237; Egypt: Tac. Ann.xu.60.), Ulpian, Dig 1.17.

RDGE 61 (Cyme). Dio Liii.16.2-3. 12 Vell.Pat. 11.59.2, Suet. ГЛ.32, BGU 1210,praef.

13 EJ2 311.1-40, Tac. Ann. 111.60.3.

Growth in the emperor's influence and control may also be illustrated by observing his relations with governors. In 22 в.с. public embarrassment was caused by Augustus' role in the misbehaviour of the proconsul Primus in Macedonia, brought to book for waging war on the Thracian Odrysae outside his province.14 Obscure though the details of the affair are, it is evident that Augustus' advice to Primus carried so much authority that it might have helped him avoid conviction for treason (maiestas)-, what was potentially embarrassing to Augustus was the alleged intermediary role of his nephew Marcellus. But later the emperor's control of governors could easily be exercised overtly. He could intervene, when convenient, in the sortition of senatorial governorships; Augustus' explicit refusal to criticize a proconsul of Crete and Cyrene for despatching a provincial to Rome suggests that he could easily have done so had he thought it appropriate; in the reign of Claudius, an inscription yields explicit evidence that the emperor might furnish senatorial proconsuls, as well his own legates, with imperial instructions (mandata) and this may well have been the case under Augustus. It is worth noting, conversely, that the prolongation of legateships by Tiberius looks from its context as if it may well have been discussed in, or at least reported to, the Senate.15

The gradual establishment of patterns of control was as much a process of trial, adaptation and evolution as design. The flexibility is most obvious in the emergence and definition of new provinces during the early Principate but it is no less significant in those acquired earlier. An established province could be defined as a specific geographical area: sometimes its boundaries were clearly delineated by natural features, but often there was no clear border, and then the province would be defined as comprising the communities in it and their dependent territoria. A new province could be delimited (confirming or modifying the area originally assigned to a military legate with imperium) and given a gubernatorial structure, a military establishment, developing communication routes and a tax assessment. Various features (none of them universal) might further emphasize the unity of a province: the existence of a charter (lex provinciae), defining the basis of taxation, the military establishment and, in broad terms, the nature of local government; the governor's provincial edict setting forth his intentions in administration; the encouragement or creation of a koinon or concilium, a federal representative assembly for the communities of the province, with a particularly important role in the organization of imperial cult.

On the other hand, the picture is far from uniform within the provinces, except for certain broad features of the military establish-

Dio liv. j. 1-4; for the uncertainty over the date see above, p. 84.

EJ2 311.40-55, Tac. ArnA.So.

ment. In many provinces, even those of long standing, the degree of military control was incomplete in less civilized regions; there could be no blanket of administrative organization and hence the role of the towns and cities was crucial. The provincial superstructure did not cut across or invalidate other pre-exisdng or developing institutions and relationships; rather, 'Romanization' went beyond simple intrusions like the building of arteries of communication or the introduction of the Roman currency and encouraged the persistence or development of certain kinds of insdtutions, fostering and moulding the relationship between Rome and individual community, between disparate elements within the provincial communities. Thus, established city-foundations in the eastern provinces might have their subjection to Rome tempered by a treaty written in the language of 'freedom' or of 'friendship and alliance', their aristocracies encouraged to undertake the burdens of civic government in return for the prospect of prestige and social advancement.16 Even in the less urbanized province of Egypt, the district capitals (metropoleis of the nomes) assumed some of the features of the Greek poleis — magistrates and a 'Greek' gymnasial class.17 Local laws (nomot) would be allowed to subsist in many places, survivals of pre-existing laws, religious and judicial institutions like the Athenian council of the Areopagus or the Jewish Sanhedrin. Where 'freedom' was maintained, the lives of the citizens might largely be conducted according to local law, but the civic magnates could easily be made to see that the 'independence' of the community was at the disposal of the ruling power.18 Even a city like Palmyra, on the fringe of the empire in the early Principate, had accepted Germanicus' instructions on the details of payment of local taxes in cash; if there was a precise moment at which it became integrated into the province of Syria, it is not clear when that was.19 An example of firmer and more overt extension of control can be seen in the west with Corbulo systematically imposing 'senatus, magis- tratus, leges' on the borders of Gallia Belgica in a.d. 47.20

Roman control did not end at provincial boundaries. As important as the patterns of control within provinces, from the point of view of the consistent desire to create the conditions for further annexation of territory, are the tentacles which reached out beyond the frontiers, signs of a presence designed to impress Roman power upon tribes and client kings. The methods used outside provinces hardly differed from those used inside and must surely have emphasized the insignificance, in important respects, of the frontier between 'Roman' and 'non-Roman'

" RDGE 26, Reynolds 1982 (в 270) no. 8. " See below, p. 696. 18 Tac. Алпли.60.6.

" CIS 11. j. 3 913.181-6 (Greek text), Matthews i984(e 1037) (translation); on Palmyra's status see J.C. Mann in M.M. Roxan, Roman Military Diplomat 1978-84 (ICS 1983), 217-19.

20 Tac. Ann.xi. 19.2-3.

35° io. provincial administration

territory. In Germany, for instance, occupation of military sites in sensitive areas beyond the frontiers is probable for a few years after the defeat of Quinctilius Varus and the loss of three legions in a.d. 9, and again in a.d. 47, but it is only part of the story. Neighbouring tribes supplied soldiers; Segimundus, the son of a Cheruscan chief, was appointed priest of the imperial cult at Ara Ubiorum, though still domiciled on the east bank of the Rhine, and Arminius' nephew Italicus was educated at Rome in the reign of Claudius; c. a.d. 2/3 the governor Aelius Catus, perhaps legate of Moesia and proconsul of Macedonia, transplanted 50,000 Getae into Thrace, Aelius Plautius Silvanus settled more than 100,000 transdanubians in Moesia in the reign of Nero; in Juba's Mauretania there were twelve Roman veteran coloniae, founded between 33 and 25 B.C. and attached to Baetica for administrative purposes; in 4 B.C. auxiliary units of Gauls were operating in Herod's Judaean kingdom.[510]

For provinces and their towns, villages and individual subjects, as for client kings and tribal chieftains, the embodiment of Roman power and authority was in practice inescapably and increasingly identifiable as the emperor. It is important to emphasize that he was far more than a mere figurehead, for his administrative role was always an active one. His position as a magistrate could be invoked (if it were ever necessary) to justify the issuance of edicts and epistulae addressed to specific provinces and communities within them, and imperial pronouncements in these forms soon hardened into a central feature of the development of a body of administrative law for the provinces. Pronouncements of a general nature which illustrate the emperor's role as an executive on a broad front are reladvely few: the Augustan measure establishing a new procedure for extortion cases is in the form of a senatus consultum but the imperial edict which prefaces it makes the emperor's central role clear; imperial edicts guaranteeing the privileges of the Jews or of veterans, or regulating the system of vehiculatio (requisitioned transport) are not limited by civic or provincial boundaries and retain validity beyond the lifetime of an individual emperor undl they are explicitly modified or superseded or occasionally, if in danger of being overlooked, reiterated.[511]

It is not difficult to see how groups of communities and individual communities and persons naturally perceived the emperor as the prime focus of power and tended to direct embassies and requests to him, normally, though not always, through the filter of the governor, as the most natural source of effective action and patronage. This impression will have been further reinforced by the evident interests of the emperor and his property {patrimonium) in many provinces and areas. Imperial reaction by verbal decision or rescript thus also became a central feature of the growing corpus of law and regulation. How much of the actual decision-making was done by the emperor in person (as opposed to the palatine bureaucracy), how much was acdon and how much reacdon does not alter the significance of the role. As the volume of business naturally increased, provincial officials multiplied; a matter brought to an emperor's attendon by an embassy might be referred back to a provincial governor for investigation, as happened at Cnidus under Augustus.[512] A significant illustration of the occasional need to define responsibility is Claudius' explicit pronouncement of a.d. 5}, amplified in a senatus consultum, that the decisions {res iudicatae) of his procurators were to be regarded as having validity equal to his own. Under Tiberius a procurator of Asia who had overstepped the mark was castigated by the emperor but neither of these acts can have entirely prevented abuse of their powers by officials.[513]

ii. structure

The functioning of the administrative system in the provinces depended upon a superstructure of military and civil officials, appointed to their positions by the central government and directly responsible to it. The relatively small corps of senators and equites who occupied the higher posts were normally not natives of the provinces in which they served, although there are sufficient exceptions, especially later in the Julio- Claudian period, to assure us that this was not an inflexible rule.[514] The infrastructure consisted of the elements of local government in the provincial communities - towns and villages - with varying degrees of autonomy. In this section these two elements will be examined in detail and some final observations will be made on the nature of the relationship between them.

Governors of all ranks, legates, proconsuls and prefects or procurators, exercised the full range of administrative, military and judicial powers within their provinces which their imperium implied; if a proconsul or a procurator had only a handful of auxiliary troops in his province, his authority over them was no weaker than that of the legate of Syria over his four legions and auxiliary troops. The governor's responsibility for maintaining the quies provinciae was paramount and Ulpian's description of his duties as they were in the early third century indicates a breadth of authority which must be valid for the early imperial period.26 Needless to say, the governor's freedom to act was subject to the will of the emperor, as it was to that of his delegated agent, be it Agrippa, Gaius Caesar, Germanicus or Corbulo, with overriding powers. The events surrounding the death of Germanicus in the East in a.d. 19 and his difficult relationship with Piso, the legate of Syria, illustrate the tensions which might arise; as they similarly might if an imperial procurator, as personal agent of the princeps, encroached on a governor's prerogatives, as is shown by the quarrel in Britain in a.d. 62 between the governor Suetonius Paulinus and the procurator Julius Classicianus which Nero attempted to solve by despatching the imperial freedman Polyclitus.27 At the other end of the spectrum, a governor's powers were, in theory, limited by the privileges of particular communities or individuals; often they no doubt chose to observe them, in practice they could certainly be overridden.

There was a variety of officials in direct subordination to the provincial governor. As far as the routine work of the governor's officium was concerned, there is very little evidence for the early imperial period but an inscription of the second century shows that his staff consisted of a retinue of lictors, messengers (viatores), slaves and soldiers (beneficiarii consulares seconded from their units); in the first century it might perhaps have been smaller but similar in character.28 At a higher level legates and proconsuls would have civil and (where there were legions) military legati-, military tribunes, commanders of auxiliary units and centurions would also play an important role in civil as well as military administration. Proconsular governors had quaestors who performed their traditional role in public finance, whilst the financial interests of the imperial property {patrimonium) were tended by a procurator provinciae (normally an eques, sometimes a freedman) with subordinate equestrian or freedmen procurators assigned to specific estates or sources of revenue. Their degree of independence from the governor cannot always be precisely measured and the issue was gradually more obfuscated by the increasingly public nature of the fiscus and the fact that in imperial provinces the procurator provinciae had, from the first, assumed the traditional duties of the quaestor in the sphere of public finance. Only in Egypt can it be clearly seen that the equestrian officials of procuratorial status acted directly as 'departmental heads' for the governor but the same may be true, and increasingly so as time

26 Dig. 1.16.4.3, 1.18.3, xlviii.18.1.20. 27 Tac. Ann.ii.)-;, xiv.38-9.

28 J.H. Oliver, AJP 87(1966), 75-80, P.R.C. Weaver, AJP 87 (1966)457-8.

passed, in other imperial provinces too.29 From these officials the governor was relatively free to select those who would assist him in their own areas of expertise by sitting on his advisory council (consilium), but he was not restricted to co-opdng a quaestor, legate, procurator or military officer; he might also summon a client king, a local magnate, a city magistrate or an expert in local laws and institudons.

The evidence for subdivision of provinces into regional administrative units is patchy and sporadic and it is impossible to imagine anything like a general pattern. In newly acquired or less Romanized areas special arrangements might be appropriate. In the Alpine regions in the early imperial period we find military praefecti assigned to groups of civitates in a region; as the regions became more organized and subjugated these praefecturae were integrated into the more regular gubernatorial pattern.30 The requirements which dictated such an arrangement were doubtless analogous to those which later produced centurions in charge of regions (centuriones regionarii) in Britain, for example, and they serve to emphasize that in many \f not all 'frontier' provinces the organization of the military establishment was inseparably linked to the development of the embryonic civil administrative structure.31 In some provinces the evidence shows the survival of traditional regional units — the three (or four) epistrategiae and their constituent nome divisions in Egypt, the strategiae in Thrace (gradually phased out from the late Julio-Claudian period), toparchies in Syria and Judaea. In some places groups of cities were agglomerated into administrative units (the Syrian Decapolis, for example), in others pagi were created perhaps mainly with a view to facilitating the organization of taxation.32 The officials in charge of such divisions will have formed an important bridge between the civic authorities and the officials with province-wide responsibility, theoretically without prejudice to whatever degree of autonomy in internal government obtained in the individual communities. Finally, it should be added that, in effect, another type of regional unit was created by the growth of large imperial estates, often embracing numbers of small communities within their boundaries and assigned to the administration of an imperial procurator. The efficient functioning of this relatively small central bureaucratic superstructure (perhaps not more than 300 officials in all) depended upon an infrastructure of effective local administration in the towns and villages of the provinces. In this respect there are bound to be striking differences from province to province and region to region, particularly noticeable in broad terms between East and West; in much of the East Rome acquired provinces which retained

® Below, pp. 682-4. 30 EJ2 243, 244. 31 Tab Vindohi(=n 250).

32 Egypt, below, p. 682; Thrace, below, p. 567-8; the Decapolis, 1СRR 1 824, cf. Isaac 1981 (d 93); Pflaum 1970 (e 75 5).

their Greek or hellenistic legacy of poleis whilst many of the western provinces required a greater degree of direct initiative in the organization of communities or tribal units into civitates, a process in which the military presence played a vitally stimulating social, economic and technical role. If a general pattern can be extrapolated from this diversity, it should probably be defined in terms of the aim of Roman imperial government to perpetuate or create a system of civic government which depended upon the primacy of the urban centre in its region and the supremacy, within that urban centre, of the wealthy aristocracy. Urbanization, thus defined, was the essence of social and political control and this process of development is one of the most important features of provincial history in the first century a.d. There was the foundation of coloniae in both the East and the West. The poleis of the East could be encouraged to better their status and their corporate privileges. In Gaul (and, to a lesser extent, in North Africa, Spain and Sardinia), existing urban centres were developed as civitates-, some of the native oppida were developed, others were replaced by new civitates which, sooner or later, could aspire to the status of a colonia or municipium.

The structure of government in the provincial poleis and civitates depended heavily upon the oligarchical institutions of councils and magistrates, based upon qualifications of wealth and birth and vested with the executive power to govern their communities internally and to represent them in their dealings with the central authority. The more broadly based assemblies, whose composition was carefully defined so as to distinguish citizens from non-native residents (incolae), constituted a more democratic element but it was one with a restricted role, exercised under the direcdon of the local Senate and the curial class.33 In some cities specific groups were permitted their own communal laws and institutions, so long as they did not infringe the laws of the city as a whole.34 Of more general importance are other sorts of civic institudons whose functions fitted into the administrative pattern and whose officials exercised power and influence and gained status and prestige: local courts, temple foundations, gerousiai (councils of elders), collegia (guilds) and associations of all kinds. The curial classes may well have played an important part in these institutions as execudves or patrons but many of them were, for others below that level, catalysts of social and political upward mobility in a pattern which systematically linked privilege and obligation and gave the ruling aristocracies the responsibility for apportioning the burdens of local government among both themselves and the lower status groups of the citizen body. The best illustration of this as a general feature of the system comes in the form of

MW4J4, cap.LIII, cf. Mackie 1983 (e 25i)ch. III.

The best known is the Jewish community of Alexandria, see CP] 1, p. 7, below, ch. 14d.

the ubiquitous public services (called liturgies in the East and munera in the West) which distributed the necessary burdens of local administration (including such functions as tax-collection for the central government) amongst the populace according to property qualification. The highly developed and organized liturgical system of the later Empire cannot safely be retrojected to the earlier period nor can it be assumed that it developed pari passu in different areas. But the vestigial and scattered evidence for the early imperial period makes it clear that the roots are to be sought here, at a time when it was probably still meaningful to make a clear distinction between such public services (whether prestigious and theoretically voluntary or, to an increasing extent, menial and compulsory) and the elective magisterial offices (honores or archai).35

Although the cities normally enjoyed a primal position in relation to the villages of their territorium, it is important to emphasize that this only rarely seems to have involved direct administration of villages from the civic centre. Some Alpine tribal villages were governed from their neighbouring municipia and in Africa magistrates of Carthage were involved in the administration of villages whose population included Roman citizens. But even there, other native settlements probably had their own magistrates and in Spain a vicus may be found acting independently of its civitas.36 In western Asia Minor and Syria village political life was vigorous, involving village assemblies, sometimes councils of elders (gerousiai), and boards of magistrates; in Cappadocia, which had been little affected by Hellenism and consequently boasted few cities, it was the villages which were at first the centres of organization and of economic and religious life; internal village administration in Egypt did not depend on the nome-capitals, though it was perhaps subject to a greater degree of supervision by government officials than was the case elsewhere. In Gallia Belgica, where some 15 о vici are known, periods of growth have been identified immediately after the conquest and in the middle of the first century a.d., involving both pre-Roman oppida and new foundations appearing close to the main roads. Here the grouping of villages in pagi and the development of the major vici as cult-centres emphasizes the variation in size and the general tendency of groups to form their own central-place hierarchies.37 An important role as a centre of market, commerce and manufacture together with the existence of a wealthy landowning (and hence magisterial) elite will have been the basis for claims to city-status which

» EJ2 31 i.j5-62, FIRA i 56,1 2i,cap.XCII.

36 Anauni and Tridentum, GCN 368.21-36; Carthaginian magistrates, ILS 1945, CIL viii.26274; Spanish vicus, AE 1933, 267; compare Hiera polls sending peace-keeping officials to villages in OGIS j27 (date uncertain). 37 Wightman 1985 (e 520) 91-6.

larger villages made with increasing frequency in the second and third centuries.

This sketch of the governmental system as consisting of a central bureaucratic structure and the local administrative institutions ignores one feature which deserves mention in this context - the existence of leagues of cities and provincial federate assemblies (koina or concilia). The former were never very widespread and where they did exist were probably a concession to local traditions (as in Greece, where limited rights of coinage were enjoyed) or a pre-existing and convenient instrument of organization in a new province like Lycia-Pamphylia. The provincial assemblies, of which only the Asian and the Gallic (serving the Three Gauls) are known in any detail during this period, played an important role in emperor-cult and might be the medium for transmission of measures affecting the province as a whole or for expressing the common grievances of the provincial cities at the imperial court, but neither they nor the leagues had a role of any vital administrative importance, nor did they occupy a regular role as intermediary between the cities and the central government; it is, however, worth noting one interesting instance from the reign of Tiberius of the Thessalian League attempting, by vote of the constituent members, to resolve an inter-city dispute which was remitted to it by the provincial governor.38 A more important feature is the fact that they allowed concentration of the city aristocracies in a broader and more prestigious context, reinforcing their standing and control in their individual cities.

Effective links between the central and the local administrative structures, nevertheless, did exist. As far as function was concerned, the main feature is the way in which the provincial authorities of the central government exercised a supervisory or controlling interest over the local, sometimes under the pressure of requests from the communities themselves. This is illustrated in more detail in the following section, but it is worth noting here first, that even if such intervention frequently went beyond what the central government would have chosen to do of its own accord, this possibility was always inherent in the relationship between Rome and the provincial community and second, that the inability of the communities to exercise their autonomy satisfactorily foreshadows the situation in the later Empire when the higher echelons of the local administration were effectively incorporated in the central bureaucracy; in the early Empire it might occasionally be expedient to send a person who already enjoyed influence at the imperial court back to his native city to regulate its affairs, as happened to Athenodorus of Tarsus under Augustus.39 Intervention by central government and the

MEJ2321. 39 Strab. xiv.j.i4 (674c).

use of local people was greatly facilitated by the opportunity for local magnates or their descendants to enter imperial service, perhaps availing themselves of the patronage of provincial governors or other powerful contacts; in doing so, they thus effectively withdrew from direct participation in local government, and deprived the communities, in the long run, of the use of their administrative capability and the resources upon which it was based. This may be seen as an inevitable consequence of the opening up of the equestrian status to the wealthier provincials. Antecedent to this might be the opportunity for a local magistrate, such as Lampo of Alexandria, to assist the provincial governor in his court or to sit on his consilium. A local dynastic family, like the Euryclids of Sparta, which gained citizenship under Augustus, could boast a member of equestrian procuratorial status by the reign of Claudius.[515]

III. FUNCTION

In contrast to the relative formality of the bureaucratic structure, an attempt to describe how provincial administration worked in practice must take account of the flexibility which the structure permitted and observe the patterns and relationships which developed in the early imperial period. A useful analysis of the working of provincial government can be presented in terms of the role of the various elements in the structure — emperor, Senate, the provincial governor and his subordinates, communities, institutions and individuals - the relationships between them and the factors which limited or determined the scope and nature of their action. Their functions can be illustrated by examples which show what kind of action they were free to take in what kind of situation and how different kinds of situations affected the complex of their interrelationships.

Here it is perhaps best to begin at the bottom of the structure and discuss the villages first. In general, they seem to have enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy in communal affairs (though this doubtless varied from region to region), electing boards of magistrates from amongst the local landholders to manage village funds, gifts and bequests, the administration of markets, temples, public buildings and common property. The democratic element in local government survived quite vigorously in the form of village assemblies which discussed substantive matters as well as making corporate dedications and honorary decrees.41 Detailed evidence for village affairs can be found only in

Egypt but we should not underrate the significance of what we know of a village like Tebtunis in the Fayum (an area particularly affected by large- scale settlement of Greeks in the Ptolemaic period) where, for instance, documents of the reign of Claudius show the administration of the village record office which kept detailed account of contractual transactions between villagers and the activity of the local guild of salt- merchants in organizing members' rights to ply their trade in and around Tebtunis.42 Here government officials played a significant supervisory role as a matter of course and, as in other provinces, the links with larger towns in the region may normally have been quite tenuous except in so far as the towns functioned as the nuclei of their regions for the purposes of taxation. Even where there were significant links with the towns a degree of tolerated independence and autonomy was not precluded but the lack of clearly defined status and privileges will have meant that small communities were more readily subject to interference and control by a provincial governor and his subordinates.43

The more abundant evidence from the provincial towns and cities naturally affords a more detailed picture. The status of the urban communities varied a good deal and the privileged cities were, at least in the early period, relatively few, of the 399 towns enumerated by Pliny the Elder in the three Spanish provinces, for instance, 291 were merely civitates stipendiariae (tribute-paying communities).44 The more favoured communities might enjoy freedom and immunity from taxation, or freedom established by charter, senatus consultum, imperial edicts or letters; but the gradual emergence of general patterns did not preclude the existence of rights and concessions specific to a single community.45 In the West the early pattern of peregrine and citizen communities defies simple classification but it is clear that, in general, elevation of status meant achievement of the status of colonia or of municipium with the Latin right, which could be confirmed by charter and which normally conferred Roman citizenship on the magistrates and their families. Native towns such as those of Spain or Africa might prepare themselves for higher status by imitating Roman institudons in their patterns of magistracies and local civil law. In consequence even in the Republic an issue in a peregrine Spanish community could be described in Roman legal language; in early imperial Africa a local magistrate marked the elevation of his town to municipal status merely by a change of title,

« PMicb 237-42, 245. « See above, n. 36.

HN hi.7, 18, 4, 117. The lists are generally agreed to be based on sources of the Augustan period.

I us Italicum: Dig. 50.15.1; senatus consulta etc.: Reynolds 1982 (в 270) nos. 8, 9, 13; rights of asylum for the temple of Zeus at Panamara: RDCE 30; income from indirect taxes given by Augustus to the Saborenses, requests for additions to be addressed to the proconsul of Baetica: MW 461.

from sufes to duovir.*6 Sometimes the process operated in reverse, for the imperial authority could diminish or revoke the privileges of a specific community or group of communities. Even when this was not done on a permanent basis, there was always the potential for a ruling by an emperor or governor which could override the rights of the community for some specific reason.[516]

Differences between the old-established poleis of the East and the developing civitates of the western provinces and the wide range of status enjoyed by the different communities does not make it impossible to identify the general features of their role in provincial government. In both East and West the privileged communities exercised their local autonomy and met their obligations to the imperial government through the institutions of councils and magistrates recruited from the propertied classes. Their role is adumbrated by Plutarch in a frequently cited passage which must primarily reflect the experience of the Greek East under Roman domination: the civic magistrate is also a subject, controlled by proconsuls, and should not take great pride in his crown of office, for the proconsul's boots are just above his head; he must avoid stirring the common people to ambition and unrest and he must always have a friend among the powerful, for the Romans are always very keen to promote the political interests of their friends.[517] In the East, as one might expect, the propertied families which provided these magnates and dynasts were frequently old-established ones which had been powerful when the poleis were city-states rather than merely provincial towns. An old aristocracy could absorb influential new elements (such as Italian immigrants), a less hellenized one could adapt to the pattern. In the West, aristocratic tribal patterns might be suitably modified to encourage the development of a pro-Roman upper class, as they seem to have been in the Three Gauls (though not so effectively as completely to suppress anti-Roman feeling).49 Free birth and sufficient wealth were the technical prerequisites of curial status; freedmen with only the latter qualification were normally debarred from office, but freedmen's sons were entitled to enter the curial order and by the second century they were to make their mark in local politics in increasing numbers.50

City government was thus essentially oligarchic. From the beginning of the second century, as the attractions of civic office faded, effective power was concentrated in the hands of an ever-smaller group which, by the later Empire, became institutionalized and appears in the legal texts as the principales (leading decurions). Many towns, however, retained democratic citizen assemblies which could theoretically exercise electoral powers and pass resolutions; by the end of the first century a.d. the electoral function had become less meaningful, as co-option to councils and appointment of magistrates by those councils became more common, but it is noteworthy that voting procedures in popular assemblies still find a place in the municipal charters of the Flavian period; popular decrees may never have been concerned with much more than the formal or honorific, but their survival in the inscriptional evidence from the Greek East is none the less significant of the fact that the assembly (demos) remained a formal element in the communal structure.[518]

Autonomy in internal administration conducted through the bouleu- tic or curial class allowed economy in the number and function of government administrators. The areas in which self-government was theoretically exercised add up to an impressive list. The regulation and organization of the councils and magistrates and other communal institutions such as gerousiai, trade- and cult-associations and gymnasia; performance of public services through a system of munera or liturgies; regulation of food supply and market facilities; general control of communal finances, including the exploitation of particular resources, management of property owned by the community, imposition of some tolls or local taxes; management of temples and cults (including some degree of control in emperor-cult once permission for its establishment had been granted) with attendant festivals and games; exercise of such specific legal powers as were permitted to individual institutions or officials (perhaps less severely limited than is commonly believed); the maintenance of public order and the supervision of prisons; sometimes rights to local coinage; organization of building projects in the town, frequently accomplished through the munificence of the local elite.

The ways in which the autonomy of communities in internal government were restricted and limited were nevertheless effective and significant. It was subject to general regulations applicable to a province as a whole, such as those embedded in a lex provinciae (which could be modified by imperial or senatorial authority) or those promulgated by individual governors; or to general enactments which affected the status and privileges of particular groups in the empire such as Jews or veteran soldiers.52 Not dissimilar was the effect of the spread of Roman citizenship through personal grants to individuals, military service and the institutions of municipal government. The citizenship extended privileges to individuals and groups which could override or curtail the hold which their community's laws and institutions had upon them. We may note the complaints made in a.d. 63 to a prefect of Egypt by a mixed group of veterans that their citizen rights were being ignored; and conversely a striking instance from the Augustan period at Chios which makes it clear that Roman citizens resident there were subject to local laws.53 An important indication of the general need to limit the scope for using Roman status to avoid local obligations occurs in the third Augustan edict from Cyrene which forbids Cyreneans with Roman citizenship to evade liturgical service in Cyrene; general recognition of this principle meant that provincial towns could continue to benefit from what was, in effect, a form of local taxation.54 But, on the whole, the upward mobility of the local elite into citizen and sometimes ultimately equestrian or senatorial status made that elite more remote from the needs and the control of the cities, which could only retain their hold by encouraging ties of patronage.

Explicit interference in city autonomy by government officials tended to become more frequent in the course of time, partly because the nature of the ruling classes in the cities was always potentially factious; when the community itself did not have the means or the power to resolve internal difficulties which resulted, it would be likely to resort to an appeal to the central authority. The invitation to intervention was bound to weaken the confidence of the Roman government in the ability of the communities to govern themselves peacefully and efficiently, and ultimately to lead to erosion of their independence.

The phenomena which most frequently demanded the attention of cemtral government were the inability to resolve internal conflicts, the reaction of communities to attempts to erode their privileges, and disputes between communities. Internal conflict evidently underlies the fourth of Augustus' Cyrene edicts, which attempts to deal with the problem of the bias of Romans against Greeks in juries dealing with noncapital cases, or the criminal accusation brought by a Cnidian embassy in 6 в.с. to Augustus and referred by him to the proconsul of Asia.55 Attacks on communal privilege are illustrated in an inscription which records the fixing of boundaries for the town of Histria and the area of

Augustan emendation of the Lex Pompeia: Pliny, Ep. x.79; governors' regulations: Lex Irnitana, cap.8; (Gonzalez 1986 (в 255)); Jews and veterans: above, п. 22.

Egyptian veterans, CCN 297; Chios, EJ2 317 (for a possible precedent from the republican period see J. and L. Robert, C/aroi I, l^ei decrett hclltnistiques (Paris, 1989) p. 64, lines 43-4).

M EJ2 511.33-62. 55 EJ2 311.62-71.

operation for a contractor of customs dues by decision of the governor of Lower Moesia, Laberius Maximus, in a.d. ioo. Earlier letters of three legates of the Julio-Claudian period are quoted, repeatedly asserting the rights of the town to revenues from fish-pickling and pine-forests in its area. One cannot but conclude from the frequency with which these rights were upheld that they were constantly under threat, presumably from contractors collecting taxes for the imperial government, as the letter of Laberius Maximus implies.[519] As for disputes between communities, reference has already been made to the case referred to the Thessalian League by a governor in the reign of Tiberius. Greater detail is to be found in a decree of a.d. 69, issued by the proconsul of Sardinia, Helvius Agrippa, dealing with a dispute between the Patulcenses and Galillenses over territorial boundaries. These had originally been established by an adjudication of a republican proconsul, recently reiterated by an equestrian governor in a.d. 66/7, apparently acting in accordance with the advice of the emperor Nero. It was this situation which the Patulcenses wished to have upheld, but the Galillenses had been encroaching on their property and had informed Agrippa's predecessor that they could produce a document (presumably the original judgment) from the imperial archives in Rome which would support their case and, by implication, invalidate whatever local documentation the governors were using. However, after two adjournments they had failed to produce it and Agrippa's decree ordered them to vacate the disputed territory.[520]Internal self-government was not the only important aspect of the role of the cities. They also functioned as guarantors of the fulfilment of obligations imposed upon them by the central government. The overall assessment of the burden of direct personal and property taxes on a province was imposed en bloc, but individual liabilities were determined on the basis of the provincial census. It was the civic authorities who were responsible for providing their portion of the tribute, and they were free to determine, at least in the cases of those taxes which were not assessed at a fixed rate, the liability of individuals, as is shown by an inscription from Messene which gives details of the division, and honours the magistrate who organized it.[521] Much of the work of collecting these taxes was devolved upon the towns who appointed local collectors and if they failed to meet their quota the responsibility for making up the deficit fell on the community. Collection of indirect taxes through farming remained common and the administration of some contracts was in the hands of the civic authorities. The same practice obtained with regard to impositions for military purposes - requisitions of supplies, the provision of transport and billeting facilities - according to a schedule which divided the burden imposed on the province between its constituent communities.59

It is not difficult to see how the interests of the central government weighed heavily on the independence of the cities in these areas, where close monitoring and liaison with provincial officials were essential. The inscription from Messene, mentioned above, states that the apportionment of the tax burden by the magistrate was carried out in the presence of the praetorian legate.60 Evidence of tax-payers failing to meet their obligations could lead provincial officials into direct intervention, either on their own initiative or at the request of the local authorities. These same officials, or sometimes the civic authorities themselves, might take opportunities to exact taxes and services above the quota, and complaints about such abuses might, on occasion, attract the attention of the provincial governor or even of the emperor; it was abuses of this kind, inter alia, which prompted the benevolent edict issued by the prefect of Egypt, Tiberius Iulius Alexander, in a.d. 68.61

The areas in which the central government exercised direct administration were very broad. The responsibilities for the military establishment, for financial affairs and for the administration of justice were interlocking and any implied division may be misleading unless it is borne in mind that, apart from the strictly military command and use of troops, a matter falling most obviously into one of these categories might also involve elements relevant to the others. The powers of officials subordinate to the governor tended to be defined by their function; a legate with judicial responsibility (legatus iuridicus) could handle cases involving property or financial matters, a military officer or a financial procurator would naturally deal with questions involving legal issues and the competence to do so was conferred by their administrative function. Even in matters of criminal jurisdiction, except for clearly defined and limited powers like the right to impose the death penalty (Jus gladii), officials enjoyed great latitude and discretion, especially in dealing with non-citizens. There were occasional attempts to define the powers of governors or procurators in a specific way (and it is probably significant that these were more frequent in the second and third centuries) but more often limits and restrictions were imposed by the limits of their administrative role and the need to observe the prerogatives of other officials and the rights of communities and individuals with whom they were dealing.62

Organization of the functions and upkeep of the military establish-

w Mitchell 1976 (в 155), cf. GCN 575, 582. 60 /G v. 1.1451.6, 10-11.

GCN 391.10-126-9, 46.

Rights of procurators and lex for the prefect of Egypt, Tac. Ann.xu.6o. 1-5; later evidence, Ulpian in Moj. et Rom. leg. toll. 14.5.1-2 (FIRA 11, pp. 577-8), C] nr.26.1-4 (a.d. 197-253).

ment in a province involved a variety of tasks, normally the responsibility of the military legates, the junior officers (tribunes and praefecti) and the centurions. Groups of soldiers or units needed to be moved around for garrison, guard or escort duties. Numbers had to be maintained by recruitment, either in the legionary recruiting grounds or, in the case of auxiliaries, in the local area or the home province of the unit. The administration of soldiers' pay and military supplies may seem to be largely internal to the army but it must be borne in mind that these, like the organization of requisitioned transport and billeting, had wider repercussions for the province as a whole in terms of the circulation of currency and the availability, collection and movement of commodities. Some of its functions brought the army into closer contact with the civilian populace — road-building, policing, supervision of mines and quarries and of other specific establishments such as mints, factories or markets, assisting in carrying out the provincial census and transporting the annona\ it is also likely that military personnel supervised the assignment of land to discharged veterans and performed an important escort role in frontier provinces when large numbers of inhabitants were moved and resettled. More crucially and not infrequently, the army was called upon to perform its peace-keeping role when civil disturbance or banditry threatened the quies provinciae,[522]

The administration of provincial finances was complex. Proconsuls had quaestors with responsibility for public finances, but in the imperial provinces this task fell on the equestrian or freedman procurators and their staffs and the regional provincial officials. The conduct of the provincial census was fundamental to the taxation system and to the general management of the controls applied to the population by fiscal means. The census, which may well have occurred at fixed intervals in all provinces although it is only sparsely attested, was probably the regular responsibility of the governor and his staff. Records of property ownership and personal status must have necessitated periodic large- scale revision, and there are likely to have been arrangements which allowed for running amendments. It was also of vital importance to maintain effective liaison with provincial communities and with the collectors and transporters of direct and indirect taxes. In some provinces management of the leasing of public land to state tenants and the collection of rents was also in the hands of provincial officials but it is impossible to make anything like a general estimate of the amount of land which fell into this category.[523]

In all provinces the procuratorial officials were responsible for supervision of the interests of the imperial property {patrimonium), ever growing and playing an increasingly important role in the public economy.65 Management of imperial agricultural estates is the most obvious feature but by no means the only one, since the patrimonium also gradually acquired widespread ownership of mines, quarries and various kinds of manufacturing establishments.66 It exercised a more general financial control through regulation of the money supply and exchange; in this sphere above all, perhaps, the blurring of the distinction between public and patrimonial interests needs stressing, for the coinage was the emperor's, the mines were owned by the patrimonium, but the organization of the volume and use of money in the provinces affected all areas of the administration.67

The very wide interests of the fiscus in Egypt are early attested in the Code of Regulations of the Special Account (Gnomon of the Idios Logos), whose operations affected the status of individuals and groups (Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, metropolites, freedmen and women, priests and soldiers), and matters relevant to property, inheritance and confiscation. It is possible that it provided the precedent for the similar extension of the role of the fiscus more generally which features prominently in later legal sources.68 The ramifications of its activity at a modest level of society are illustrated in detail by a group of papyri from the village of Socnopaiou Nesos in the Fayum concerning a dispute between two villagers named Nestnephis and Satabous.69 In a.d. 12 Nestnephis assaulted Satabous and stole a mortar from his mill. Satabous sent letters of protest to the chief official of the nome (the strategos), his assistant, a centurion named Lucretius and the prefect of Egypt, informing them of this attack. Whether the matter was investigated we do not know, but in a.d. 14/15 Nestnephis sent a statement to the royal scribe of the nome accusing Satabous of having added, in that year, some vacant land (adespotos), which was technically the property of the Idios Logos, to a house which he had purchased in a.d. i 1. The official in charge of the Idios Logos, Seppius Rufus, placed the matter on the prefect's assize list and the disputants were summoned to appear in Alexandria. In fact, Satabous did not appear and the investigation, largely conducted through correspondence, extended into the next year. The upshot was that Satabous was compelled to pay the sum of 5,500 drachmas to the Idios Logos for the land. This affair also illustrates the wide scope and variety of'legal business' and emphasizes the impossibility of isolating it

The much debated question of the relationship between patrimonium and fiscus is here avoided, cf. Millar 1963 (d 148), Brunt 1966 (d i 16) and above, ch. 8.

Evidence for agricultural estates and other imperial properties collected by Crawford 1976 (d 125), Millar 1977 (a 39) 175-89. 67 See above, ch. 8.

68 BGU 1210, cf. P0*7 3014. 64 Documents listed by Swarney 1970 (e 972) 41-2.

from other areas of administration. Provincial governors, legates and some procurators had jurisdictional powers in both criminal and civil matters. Governors and their legates, usually acting with the advice of a consilium, would deal with hordes of cases, petitions and disputes during their assize tours. The assize circuit (conventus) is central to the judicial administration of the provinces since it provided the only opportunity for dealing with business outside the provincial capital. Even so, it was far from comprehensive and, from the point of view of the provincial subject, the elements of time and space might be decisive: for almost everyone outside the capital and for almost all the time, the governor was not to hand. Naturally, the governor would not expect to deal with all judicial matters himself. Some cases could be directly delegated by provincial officials to appointed judges or jury-courts; subordinate officials in the hierarchy are also to be found performing judicial functions in matters arising within their administrative competence whilst civic authorities and institutions were permitted to retain defined and limited jurisdictional powers. For each governor, his province generated a mass of criminal charges, major or minor disputes between central government and an individual community or subject, between one community or one individual and another. Cases of murder, criminal assault, public violence or treason (maiestas) would naturally attract the attention of the governor, who possessed the power of capital jurisdiction, or even the emperor. Disputes between communities over property or rights to revenue, between individuals over contracts, property, inheritance, public liability or questions affecting the status of particular persons or groups might also do so, especially if the parties concerned were persistent, but many such matters were doubtless settled by officials lower down the hierarchy.

In matters dealt with at the highest level, procedure was relatively clear-cut. The first and second Augustan edicts from Cyrene present a fairly straightforward picture of the emperor responding to a provincial embassy and regulating the composition of jury-courts which heard cases delegated by the governor, and dealing with an individual sent from the province, perhaps under suspicion of maiestas.10 Further down the hierarchy there was a great deal more uncertainty and confusion, as is sharply illustrated by the experiences of St Paul at Jerusalem. There, it was a tribune who arrested Paul during riots, but then allowed him to address the Jews; after further unrest he ordered Paul to be examined by scourging but on discovering that he was a Roman citizen he detained him, released him the following day to appear before the priests and the Sanhedrin but fearing another riot after his address, took him back to the barracks. After discovering a plot against Paul's life, the tribune wrote to

'о EJ2 311.1-55- the governor Felix and sent Paul under armed escort to Caesarea. The trial before Felix was inconclusive and Paul was held in detention. Two years later the Jews again initiated a prosecution before Festus, the successor of Felix. On this occasion Paul produced his famous appeal to Caesar and Festus, after consulting his advisers, felt compelled to allow it. But a few days later Festus took the opportunity to discuss the matter with the client king Herod Agrippa II, the upshot of which was a second hearing for Paul before Festus and Agrippa. After Paul's defence Festus and Agrippa conferred and concluded that Paul had done nothing to merit death or imprisonment and Agrippa remarked that he could have been discharged if he had not appealed to the emperor.71 Earlier episodes in Greece emphasize the blurring of the lines of demarcation between the jurisdiction of the civic authorities and that of the provincial officials. At Philippi Paul and Silas had been brought before the local magistrates in the market-place by the owners of a slave girl and were ordered to be stripped, beaten and thrown into jail. Later, however, alarmed by the discovery that they were Roman citizens and therefore entitled not to be punished in this way, the magistrates ordered their release. At Corinth it was the Jews who had taken Paul before the proconsul's court but Gallio, who happened to be on the spot, considered it a matter of internal Jewish Law, refused to judge the case and disregarded the beating of the synagogue leader.72

The incoherence of the system, if it can be called such, has recently been described in terms to which the evidence of the Acts of the Apostles gives point: 'The process might involve individuals of the same or differing status, Roman or non-citizen, local communities or officials, Roman officials or any combination. No matter, either, that all manner of processes jostle each other: in trial by jury in the provinces or at Rome on charges established by statute; inquiries into conduct alleged by informers to be criminal; civil cases brought by litigants; arbitration between communities and decisions administrative rather than legal; police action .. ,'73 From the government's point of view it had two outstanding virtues: it was very flexible and economical with the time and energies of the officials available and, by and large, it worked.

IV. CONCLUSION

From one point of view, the provincial administration can be analysed in terms of the complex of coexisting relationships between the different elements, the emperor, the provincial governor and his subordinate officials, the province, the provincial communities as a group, the individual community and finally the individual subject. There is a

71 AA 21.j1-26.52. 72 AA 16.16-40, 18.12-17. 73 Levick 198) (d 98) 46.

temptation to argue (especially on the basis of the more abundant evidence for specific detail from the Roman East) that policy-making was not part of the dynamics of this complex of relationships, that the empire was governed, in effect, by a series of ad hoc decisions, the formation of which was significantly influenced by precedent. This is clearly a valid characterization of one aspect of provincial administration and it is true that observable change was rarely comprehensive and sharp, rather a series of gradual modifications. One noticeable feature is the flexibility of administrative practice and this emphasizes the importance of reaction to specific stimuli which might or might not harden into patterns and rules by the discriminating application of precedent; discrimination occurs when a decision has to be made as to whether a matter is to be dealt with in the same way as some previous, similar case or whether some new solution is to be devised. This might be described as, in essence, a system of rule by case-law with an infinite capacity for fine tuning according to the particular circumstances. Relevant circumstances might include the nature of the province, features surviving from the pre-Roman era, the status of the community, institution or individual, the positions and powers of the officials involved. Roman provincial government was not a matter of deciding, a priori, how administration was to be conducted and fitting any situation into a preordained procedure. Rather, it worked because of its capacity to grasp the essential point of any issue, to deal with it according to the means available and certain general notions governing the relationship between the imperial power and its subjects and, once dealt with, absorb it into a developing mosaic of flexible patterns and institutions.

It is notoriously difficult to extract from the items of evidence which illustrate specific cases and different relationships in action any coherent notion of an emperor forming or implementing a 'policy of provincial administration'; even less do we have programmatic statements which explicitly set out any such broad view, except in terms of general benevolence or intention to rectify known abuses. If consistent themes and policies are to be observed in the Julio-Claudian period and credited to the vision of particular emperors, they have to be drawn from disparate individual items of evidence, unevenly spread in time and space, or from observable trends: the spread of Roman citizenship, particularly in the reigns of Augustus and Claudius; the encouragement of urban communities and their aristocracies (especially in the West, where it was intimately linked to the spread of citizenship through the spread of colonial and municipal status); growth of communicadon systems; integration of the economic structures of town and country; the fostering of trading links within the structure of a relatively coherent

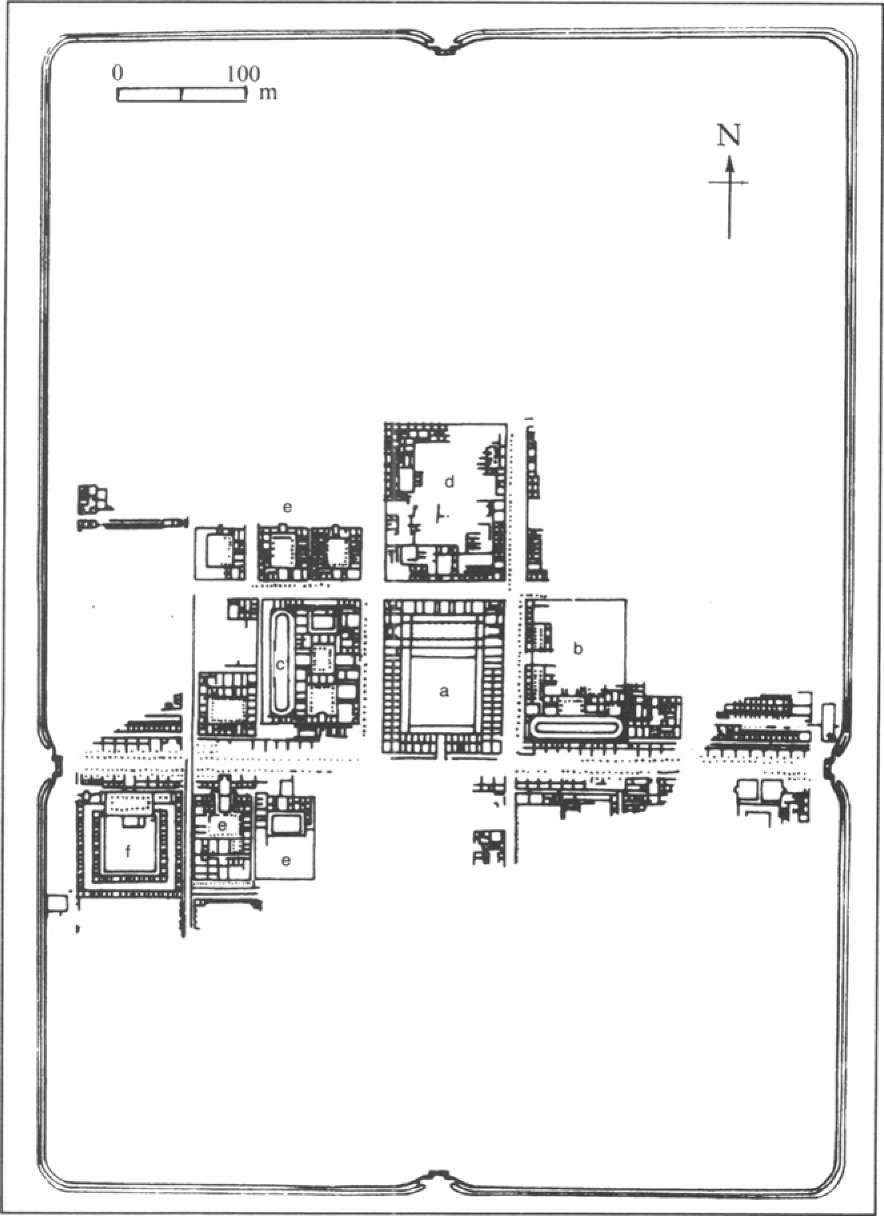

Table 2 Provinces and governors at the end of the Julio-Claudian period

Province

Title

Rank

Remarks

SICILIA SARDINIA

HISPANIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

TARRACONENSIS

BAETICA

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

LUSITANIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

NARBONENSIS

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

AQUITANIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

LUGDUNENSIS

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

BELGICA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

GERMANIA SUPERIOR

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

LYCIA-PAMPHYLIA

CYPRUS

SYRIA

Proconsul Proconsul

Ex-praetor Ex-praetor

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Proconsul

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Procurator

Ex-praetor Ex-praetor Ex-consul

Eques

JUDAEA

GERMANIA INFERIOR

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

ALPES MARITIMAE

Procurator

Eques

ALPES COTTIAE

Procurator

Eques

ALPES POENINAE

Procurator

Eques

BRITANNIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

RAETIA

Procurator

Eques

NORICUM

Procurator

Eques

DALMATIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

MOESIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-consul

THRACE

Procurator

Eques

MACEDONIA

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

ACHAEA

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

ASIA

Proconsul

Ex-consul

BITHYNIA-PONTUS

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

GALATIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

CAPPADOCIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

Coupled with Alpes Poeninae until a.d. 47

Cf. ch. 13h

Governed by praefectij procuratores earlier in the Julio-Claudian period and again under the Flavians, cf. ch. 15 b

Until the reign of Domitian, these were military commands rather than provincial governorships, cf.

ch. I}/

During Nero's Parthian War governors were ex-consuls. At the beginning of the Flavian period the governor was an ex-praetor but the post was later upgraded again.

Included Cilicia Campestris from c. 44 b.c. - c. a.d. 72 Governed by an equestrian procurator until the outbreak of the First Jewish War (a.d. 66). During the war the command was held by Vespasian as consular legate. Thereafter it was normally governed by a Leg.Aug.p.p.

Table 2 {cont.)

Province

Title

Rank

Remarks

AEGYPTUS

Praefectus

Eques

CRETE-CYRENE

Proconsul

Ex-praetor

AFRICA

Proconsul

Ex-consul

NUMIDIA

Leg.Aug.p.p.

Ex-praetor

Cf. ch. i 3i

MAURETANIA

Procurator

Eques

Coupled in a.d. 68/9 and again

CAESARIENSIS

(under a Leg.Aug.p.p.) in

MAURETANIA

Procurator

Eques

a.d. 7ĵ

TINGITANA

fiscal and taxation system in which (it has been argued74) the volume of currency was adjusted in a rational manner; a military establishment which infused new urban, social and economic structures into new provinces and a frame of mind which always aimed to ensure the security and peaceful development of territory in possession whilst keeping open the options for further expansion.

74 Lo Cascio 1981 (d 144).

CHAPTER И THE ARMY AND THE NAVY

LAWRENCE KEPPIE

i. the army of the late republic

By the middle of the first century B.C. the Roman army had developed over centuries of all but continuous warfare into a professionally minded force. At least fifteen legions (a total of about 60,000-70,000 men) were maintained in being each year, their manpower drawn from all Italy south of the Po. Military service was the duty of every Roman citizen aged between seventeen and forty-five. Those who enlisted were usually held for at least six years of continuous service, after which they could look for discharge. In law they remained liable for call-out as evocati to a maximum of sixteen years (twenty years in a crisis).1 Some men were happy to remain in the army well beyond the six-year minimum and constituted a core of professionals for whom soldiering had become a lifetime's occupation; but conscription was employed throughout the late Republic, and it should not be imagined that the legionaries were always predominantly volunteers. Until the later second century, cavalry was formed from the equites (as the name implies), who might be expected to serve three years, with a maximum of ten. Thereafter Rome looked to her allies, in Italy and beyond, to make up the deficiency. (In theory the equites remained liable for service, but were not called upon.)

At first, military service had been viewed as an essential public duty: only men with substantial property were permitted (or could afford) to serve. However, the property-requirement was gradually reduced, and from the time of Marius no more is heard of it. No pay was at first considered necessary, but from the early fourth century a payment {stipendium) was introduced to cover out-of-pocket expenses; in Poly- bius' day (f. 160 B.C.) the stipendium stood at one third of a denarius per day, an annual rate of 120 denarii.2 Soldiers looked to supplement it with booty. The stipendium was 'doubled' by Caesar, probably about 49 b.c.,

1 Knowledge of the length of servicc rests on Polvbius (vi.19.2), but the text is corrupt. The manuscripts give ten years in the cavalry and six in the infantry as the normal scrvicc requirement. The latter figure is generally emended to sixteen, given that it should be more than that required for the cavalry (cf. Tab. Hcraclcensis, 11Л 608 (. 90). Sixteen years were established as the scrvicc norm by Augustus in 1 j b.c. (Dio liv.25.5, and below, p. 377). 2 Polvb. vi.39.12.

371

to 225 denarii.[524] Out of this sum the soldier had to pay towards his food, clothing and weaponry.[525] Soldiers were armed with an oval shield (scutum),[526] one or more throwing javelins (pi/a), a short sword of Spanish origin (gladius), a dagger (pugio), and a bronze helmet. They wore shirts of chain-mail over a leather tunic, and leather sandals.

The individual legion was a body of some 4,000-5,000 men divided into ten cohorts; in battle these could be arranged in three lines, but other dispositions are known. Each cohort was made up of six centuries, each commanded by a centurion. The centurions were soldiers of many years' experience, normally promoted from the ranks. The legions were given numerals on formation, and might remain in service for several years; but there was no permanent 'army list'.

The legions of a province came under the direct control of the proconsul or propraetor who was its governor. The legions raised each year were distributed according to current needs; some provinces had no legions at all, and might lie exposed to unexpected attack. The legion had no individual commander, but day-to-day responsibility lay with the military tribunes, six to each legion, who held command by rotation in pairs. This lack of a single permanent commanding officer in the legion had not seemed very important when armies were small and under the direct eye of the proconsul or propraetor, but as armies grew in size and the geographical extent of provinces and areas of military operations increased, some delegation of responsibility became essential. From the later third century legates were appointed, to act as assistants to the magistrate. These legates were senators, varying in age and military experience, to whom some part of the military or juridical duties could be delegated. Legates were placed in command of one or more legions, but had no long-term link within any particular unit.

No rewards were envisaged at the end of the individual's military service; men returned home to their families, to take up the threads of civilian life. Only in exceptional circumstances might they be specifically rewarded for their years of service, with a cash donative at the time of a triumph, or with a land grant on discharge, should their commander make a special effort to obtain it.

The legions had always been supported in battle by contingents drawn from their allies. Up till 90 в.с. these consisted mainly of detachments from the towns of Italy, grouped together to form alae sociorum. In addition infantry and cavalry had been, and continued after 90 в.с. to be, raised in the provinces and from allied kingdoms, often those in the immediate area of the war zone; each group served under its own chieftains and aristocracy, with Roman praefecti in overall control. Some regiments, including bodies of Cretan archers and Numidian cavalry, seem to have been kept in Roman service on a more permanent basis, and served throughout the Mediterranean.

Just as the size of the army fluctuated according to the needs, of the moment, so also did the navy. Only a few ships were maintained in permanent commission in Italian ports or in dock, to be supplemented by the summoning of squadrons from allied states in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. A governor might appoint one of his legates to command such fleets; the ships' captains offered him professional advice. The lack of a navy adequate to keep sea lanes open was particularly evident in the 70s в.с. when pirate squadrons from bases in Cilicia operated openly and with success in the Mediterranean.

ii. the army in the civil wars, 49-30 b.c.

The onset of civil war in 49 в.с. between Caesar and the legitimate forces of the Republic brought a swift military build-up. The legions then serving under Caesar in Gaul, numbered in a set sequence from V to XIV, formed the basis of his army thereafter. In the months following the invasion of Italy and during his consulship in 48, Caesar formed many more legions, probably numbered I—IV (the numerals traditionally reserved each year for the consuls to use) and from XV to about XXXIII. After Pompey's defeat three or four more were formed out of the latter's soldiers, so that by 47 в.с. the number of legions in service stood at a minimum of about 36-8; all but a few had been raised or reconstituted under Caesar's direct command. With the ending of effective resistance, Caesar's longest serving legions (composed of men who had been with him in Gaul and who had over the years agitated several times, and with good cause, for release) were discharged and settled in colonies in Italy and southern Gaul. New legions were raised to replace them. Caesar evidently intended a tight grip over Roman territory, some of it newly won. Sixteen of the legions, drawn largely from the garrisons of Macedonia and Syria, were to participate in the planned Parthian campaign.